EPINEPHELUS spp.

HISTORY

The estuarine grouper, Epinephelus spp. is widely found in the coastal waters of Malaysia. The taxonomy of the grouper is often confusing, and in Malaysia the species cultured include E. suillus, E. tauvina and E. malabaricus. Grouper culture in netcages was first introduced into Malaysia in 1973 using wild caught fry. In May 1989, the Tanjung Demong Marine Fish Hatchery, Department of Fisheries, succeeded in the spawning of E. suillus, and since early 1990 succeeded in the larval culture of the grouper on an experimental scale. In 1988 about 968 tonnes of grouper were produced. In order to ensure sustainable development of the aquaculture industry and to make it more competitive with other economic activities, there is a constant need to develop appropriate and more cost-effective systems for aquaculture. Research has to be carried out on both the hatchery and grow-out phases, covering optimum stocking densities, disease prevention, optimum enclosure designs etc., including suitable offshore seafarming systems in order to overcome the increasingly frequent mortalities of cage-cultured fish in inshore waters. One major constraint in finfish culture is the poor supply of trash fish as fish feed or suitable compounded feeds within the means of the operators. Research needs to be undertaken to overcome this problem as well as develop cost-effective systems for the production of live food organisms required in the seed production phase. In the case of culture operations still dependent on the often inconsistent supply of natural or wild seeds, particularly in the culture of groupers, research has to be stepped up on the setting up of commercially viable hatcheries/nurseries.

CULTURE PRACTICES

Grouper culture is normally carried out alongside other marine/brackishwater finfish such as seabass (Lates calcarifer) and snapper (Lutjanus johni, Lutjanus argentimaculatus) in floating netcages. The culture is generally operated by a group or family-unit system. The rafts, commonly measuring 7m × 7m, are normally constructed of wood beams or thick bamboo poles (10–12 cm in diameter). Each raft consists of four netcages measuring 3m × 3m with a depth ranging between 1.5–2 m. Plastic or polystyrofoam drums are usually used as floats. Initial stocking density of fry (2–5 g in weight) is 100–150/m2. The fish are fed twice a day with chopped trash fish and rarely with pelleted feed. Culture period is about 6–8 months during which time the fish attain a marketable size of about 600– 800 g. The method for harvesting marketable size fish is simple and involves just a scoop of reasonable size which is inserted into the netcage through its cover. At present, there is no standardized method for transporting live fish. The farmers use whatever method of their liking to transport the fish. After harvesting the fish are usually kept in cement tanks for some time, for various reasons, before they are sold to restaurants or fish wholesalers. Aeration is seldom used. One major constraint in this culture is the shortage of seed supply which at the moment is totally dependent on the wild. Another big constraint is the short supply of trash fish. The nutritional requirements of the various stages of the grouper have yet to be studied and there is a need to develop a cost-effective formulated feed to replace trash fish as the major food type, as well as the production of live food organisms required particularly in the seed production phase. The culture of this finfish species is still poorly practiced, due to the above reasons, however it is hoped that with the introduction of various incentives by the Government, along with ongoing related research and development programmes, further development will be promoted. These incentives include pioneer status, investment tax credit and export incentives.

| STATUS | SPECIES |

|---|---|

| E. suillus, E. tauvina and E. malabaricus | |

| Source of seed | Wild |

| Culture method | Floating netcage and pond |

| Yield/ha | NA |

| Marketing | Domestic and export |

| Production area | NA |

| Level of culture | Developing |

| Major constraints | Limited fry supply; Limited trash fish; Poor feeds |

LATES CALCARIFER

HISTORY

The seabass (Lates calcarifer) is widely distributed in coastal waters throughout Malaysia. Seabass culture in netcages was first started in Malaysia in the mid 1970s, using wild or imported fry. Larval rearing of the seabass was first developed by the Fisheries Research Institute in Glugor, Penang in 1982, using wild broodstock caught from the waters of Telok Air Tawar, Penang. The first successful spawning and breeding of seabass raised in captivity was achieved at the Tanjung Demong Marine Fish Hatchery, Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture in Terengganu in July 1985, and by 1989, over 114,000,000 fingerlings were produced. At present, culture of seabass in ponds and netcages is sustained mainly by locally produced as well as imported fry, coming mainly from Thailand. In 1989 about 1,538 tonnes of seabass were produced. In order to ensure sustainable development of the aquaculture industry and to make it more competitive with other economic activities, there is a constant need to develop appropriate and more cost-effective systems for aquaculture. Research has to be carried out on both the hatchery and grow-out phases, covering optimum stocking densities, disease prevention, optimum enclosure designs etc., including suitable offshore seafarming systems in order to overcome the increasingly frequent mortalities of cage-culture fish in inshore waters. One major constraint in finfish culture is the poor supply of trash fish as fish feed or suitable compounded feeds within the means of the operators. Research is required to overcome this problem as well as to develop cost-effective systems for the production of live food organisms required in the seed production phase.

CULTURE PRACTICES

The giant seabass (Lates calcarifer) is the most important finfish species for seafarming, due in large measure to the increasing availability of artificially produced fry and fingerlings of this species. Seabass culture is normally carried out alongside other marine/brackishwater finfish such as grouper (Epinephelus suillus, Epinephelus tauvina and Epinephelus malabaricus) and snapper (Lutjanus johni and Lutjanus argentimaculatus). The culture is generally operated by a group or family-unit system. The floating rafts, measuring 7m × 7m, are usually constructed of wood beams or thick bamboo poles. Each raft consists of four netcages measuring 3m × 3m with a depth ranging between 1.5–2 m. Plastic or polystyrofoam drums are usually used as floats. Initial stocking density of fry measuring 5–10 cm is 100–150/m2. When the fish attain a size of 12–15 cm the stocking density is reduced to 40–45/m2. The fish are fed twice daily with chopped trash fish and rarely with pelleted feed. They are reared for about 5–9 months until they reach the marketable size of about 600 g. The method for harvesting marketable size fish is simple and involves just a scoop of reasonable size which is inserted into the netcage through its cover. At present, there is no standardized method for transporting live fish. The farmers use a method of their own liking to transport the fish. Although a few ponds are used for seabass culture, especially in the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, this practice has not expanded as much as netcage culture, probably owing to the high cost of land as well as high initial investment costs. Although hatchery production and larval rearing techniques have been demonstrated by the Department of Fisheries since 1982, commercial rearing by the private sector has not caught on in a big way. Larval mortalities in the hatcheries still occur occasionally without the cause/causes being definitely identified. The nutritional requirements of the various stages of the seabass have yet to be studied, and there is a need to develop a cost effective formulated feed to replace trash fish which is becoming in short supply.

| STATUS | SPECIES |

|---|---|

| Lates calcarifer | |

| Source of seed | Artificial and wild |

| Culture method | Floating netcage and pond |

| Yield/ha | NA |

| Marketing | Domestic and export |

| Production area | NA |

| Level of culture | Developing |

| Major constraints | Limited fry supply; Limited trash fish; Poor feeds |

LUTJANUS spp.

HISTORY

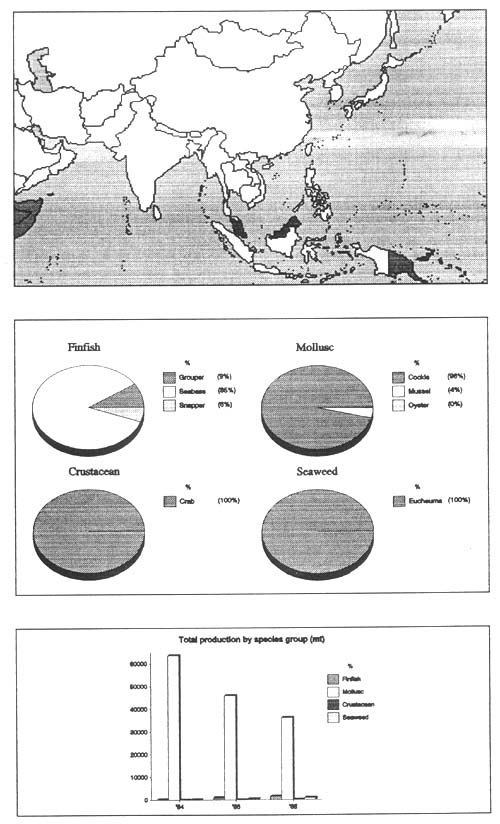

Malaysia's total aquaculture production in 1989 amounted to 53,118 tonnes, while the overall total fish production for the year was 882, 492 tonnes. Although aquaculture production constituted only 6.0% of the overall fish production in 1989, the total production from aquaculture showed an increase of 13.1 % over the previous year's production of 46,957 tonnes. Culture of fish in netcages was introduced into Malaysia in 1973. Among the species of fish cultured in cages are the mangrove snapper, Lutjanus johni and the red snapper, Lutjanus argentimaculatus. Between the two, the mangrove snapper is the more commonly cultured. To date, there is no hatchery production of fry for these two species and all the fry are obtained from the wild. In 1988 about 123 tonnes of mangrove snapper were produced, while the combined total production of the two species in 1989 was 590 tonnes. Snappers are also very popular species for seafarming, but their culture expansion is presently constrained by the lack of natural seed, and technology for artificial seed production, which is only at the early stage of development. Among the major aquaculture research and development topics considered by the Department of Fisheries to be essential for the future development of seafarming include: (i) improvement and development of appropriate and cost-effective breeding and culture systems and (ii) development of aquaculture feeds. Research has to be carried out on both the hatchery and grow-out phases, covering optimum stocking densities, disease prevention, optimum enclosure designs, including suitable offshore seafarming system in order to overcome the increasingly frequent mortalities of cage-culture fish in inshore waters.

CULTURE PRACTICES

The culture of snapper is normally carried out alongside other marine/brackishwater finfish such as seabass (Lates calcarifer) and grouper (Epinephelus suillus, Epinephelus tauvina and Epinephelus malabaricus) in floating netcages. The culture is generally operated by a group or family-unit system. The rafts, measuring 7m × 7m, are usually constructed of wood beams or thick bamboo poles. Each raft consists of four netcages measuring 3m × 3m with a depth ranging between 1.5–2 m. Plastic or polystyrofoam drums are usually used as floats. Fry are caught exclusively from the wild. Initial stocking density of fry (2–5 g in weight) is 100–150/m2, and when the fish attain a size of 50–100 g the stocking density is reduced to 40–45/m2. The fish are fed twice a day with chopped trash fish and rarely with pelleted feed. Culture period is about 6–8 months during which time the fish attain a marketable size of about 600–800 g. The method for harvesting marketable size fish is simple and involves just a scoop of reasonable size which is inserted into the netcage through its cover. At present, there is no standardized method for transporting live fish. The farmers use whatever method of their liking to transport the fish. After harvesting the fish are usually kept in cement tanks for some time, for various reasons, before they are disposed. Aeration is seldom used. A major constraint in this culture is the short supply of trash fish. The nutritional requirements of the various stages of the snapper have yet to be studied and there is a need to develop a cost-effective formulated feed to replace trash fish as the major food type, as well as the production of live food organisms required particularly in the seed production phase. The culture of this finfish species is still poorly practiced, due to the above reasons, however it is hoped that with the introduction of various incentives by the Government, along with on-going related research and development programmes, further development will be promoted. These incentives include pioneer status, investment tax credit and export incentives.

| STATUS | SPECIES |

|---|---|

| L. johni and L. argentimaculatus | |

| Source of seed | Wild |

| Culture method | Floating netcage |

| Yield/ha | NA |

| Marketing | Domestic |

| Production area | NA |

| Level of culture | Developing |

| Major constraints | Limited fry supply; Limited trash fish; Poor feeds |

ANADARA GRANOSA

HISTORY

Cockle culture (Anadara granosa) is by far the most important and organized aquaculture industry in Malaysia. Cockle culture was first carried out in 1948 by a village headman who transplanted natural seeds to his village in Began Panchor, Perak. Its natural distribution is largely limited to the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia extending from Kedah in the north to Johor in the south, however seed have been found along the east coast especially in sheltered coastal areas in Pahang. It was a great success and since then cockle culture has flourished over the years and its production has represented more than 85 % of the total aquaculture production in Malaysia over the past 2–3 decades. This has been made possible by the abundant supply of natural seeds, extensive areas of mudflats on the sheltered west coast of Peninsular Malaysia suitable for cockle cultivation, and the favourable market demand. Mass culture of cockles is being practised by cooperatives along the west coast and in some lagoons in the east coast. In 1980 some 121,000 tonnes were produced, however from 1981 to 1988, production has fluctuated between 35,000 to 60,000 tonnes. Some 4,000 hectares were utilized for the culture in 1988. Seed production has also fluctuated between 6,200 tonnes and 13,350 tonnes between 1985 and 1988. In 1988 some 8,220 tonnes of seeds were landed. Artificial propagation of cockle seed was successfully carried out in the mid' 1980's but was not followed up because of the high cost in production. Recent research conducted by the Fisheries Research Institute in Penang has verified the optimum duration for culture in order to obtain maximum production and determined possible new sites for cockle culture production.

CULTURE PRACTICES

Some 4,000 hectares of mud-flats fringing the coastline of Kedah, Penang, Perak, Selangor and Johor have been used successfully for the culture of the cockle, Anadara granosa. Cockle seeds are collected when they fall within a size range of 4–10 mm. When spat collection is sanctioned by the Department of Fisheries, local fishermen move to the spatfall areas and start collection when the tide drops and the water covering the mudflats is 60 cm deep. The spats are collected by means of a wire basketshaped device with a gap of approximately 2 mm between the wires (mesh size). Seeds are stocked in open mud-flats and culture plots are only demarcated at the four corners by “bakau” poles (Rhizophora sp.) or “nibong” poles (Oncosperma tigillaria). Cockle seeds are relayed from the natural beds to the culture areas when they range between 4–10 mm in size i.e. 6–8 months old. Prior to stocking, the culture beds are cleared of other shells including predatory gastropods. An initial stocking density of 1,000–1,500/m2 and a final stocking density of 200–300/m2 before harvesting are recommended. Fast growing individuals are removed from time to time to ensure more uniform growth. Predators such as gastropods (Natica maculosa and Thais carinifera) are removed on a regular basis. Cockles are harvested daily when they have attained the minimum size of 31.8 mm i.e. about 1–1.5 years old. One whole culture bed is usually fished out 12–15 months after seeding. Both harvesting and thinning is done from a motorized, shallow-draft vessel using a dredge similar in design to that for collecting spat except that it is larger and more robust. The dredge is affixed to the end of a long pole. The boat is usually manned by two men one of whom maneuvers it while the other thrusts the dredge into the mud and holds it there as it drags along. Penang, Perak and Selangor are the major cockle producing states in Malaysia. The size of culture bed ranges from 0.4–400 hectares. Between years certain plots are left unseeded as it is believed that it improves the “condition” of the ground. The potential area suitable for the culture of the cockle is estimated to be 12,800 hectares of mud-flat.

| STATUS | SPECIES |

|---|---|

| Anadara granosa | |

| Source of seed | Wild |

| Culture method | Bottom |

| Yield/ha | 40 mt/ha |

| Marketing | Domestic and export |

| Production area | 4,000 ha |

| Level of culture | Developed |

| Major constraints | Limited seed supply; Marketing |

PERNA VIRIDIS

HISTORY

By aquaculture production, the green mussel, Perna viridis, ranks as the second most important bivalve species in Malaysia. Based on the work carried out by the Fisheries Research Institute in Penang and the support services provided by the government, mussel culture has shown significant development in recent years. Prior to systematic culture, mussels have been collected mainly from fishing stakes, fish cages and from jetties. Experimental raft culture was successfully demonstrated by the Fisheries Research Institute, Glugor, Penang during the mid-seventies. However, since the experimental culture, the culture of mussel has expanded rapidly particularly in Johor where more than 60 culturists managing more than 200 rafts (15,000 m2) are currently involved in the culture of this bivalve. Other important culture areas are found along the coastline of the states of Melaka and Perak where natural spat are available. Some 1,368 tonnes of shell-on mussels were produced in 1988. The Department of Fisheries launched the mussel transplantation programme (of young mussels collected usually on polypropylene ropes from the straits of Johor) in 1986 and to date some 39 new sites with an estimated area of 25 hectares have been identified suitable for mussel culture. The culture is dependent solely on the natural seed production. With the production system already developed and mussel culture now spreading to other parts of the country, production is projected to considerably increase in the near future possibly surpassing that of the carpet shell, Paphia. One major constraint in the expansion of mussel culture in Malaysia is the poor consumer demand and market price for this product.

CULTURE PRACTICES

Three culture methods are currently in use for the culture of the mussel, Perna viridis i.e. raft, stake, and rack methods. The raft culture method is carried out in relatively sheltered locations with a water depth of 3–5 m. The stake method is in use in areas with water depth of 2–3 m during mean low water neap and these areas are generally more exposed and the current movement is quite strong (> 0.35 m/sec.). The rack method requires a platform from which the strings of mussel seeds are suspended into the water column. The rack method is normally used in areas where the tidal difference between low and high tide is not very great. The collectors commonly in use for spat collection include nylon net, polyethylene net and mangrove poles. When sufficient seeds (1–1.5 cm) are collected (800–3,000 spat/m of rope) they are ready for transplanting from the natural area to the culture sites. The stocking density which is commonly used is 3–5 strings/m. The mussels are suspended from the rafts, racks or poles in the water column about a metre from the substratum to minimize predators such as starfish and predatory gastropods. To ensure uniform growth, larger and faster growing individuals are removed and transferred to other strings. The potential area for mussel culture in Malaysia is estimated to be more than 500 hectares. The culture period from a mean size of about 2 cm to about 5–6 cm takes about 5– 10 months depending on the suitability of the culture site. In a good culture area it takes from 4–6 months to reach the marketable size. Generally, larger mussels are removed to allow the smaller ones to grow for a further period. Marketable mussels are landed and are sold either directly to wholesalers or retailers. After drying and cleaning, the collecting ropes can be re-used for spat collection. It has been estimated that the yield from raft culture of mussels (based on 350 rafts/ha and 2 cycles of 450 kgs per raft per annum) is 315 tonnes of shell-on mussels per ha per year. Mussels are presently marketed as a fresh shell-on or fresh shucked product in Johor. Some are dried or canned but the quantity is still very small.

| STATUS | SPECIES |

|---|---|

| Perna viridis | |

| Source of seed | Wild |

| Culture method | Suspended (raft & stake) and bottom |

| Yield/ha | 315 mt/ha/year (shell-on) |

| Marketing | Domestic |

| Production area | > 100 ha |

| Level of culture | Developed |

| Major constraints | Limited seed supply; Marketing |

CRASSOSTREA spp., OSTREA sp.

HISTORY

Oyster culture in Malaysia is not well developed with annual productions still rather low. On-bottom culture of the oyster (Crassostrea belcheri) in Sg. Muar, Johor has been carried out since the early 1950's. Experimental culture of oysters was first carried out by H. Okada from 1960–1963. The culture of the mangrove oyster, Crassostrea belcheri was successfully carried out by the Sabah State Fisheries during the early seventies. The culture of the flat oyster, Ostrea folium L. was successfully demonstrated in Pulau Langkawi in the late 1970's, but because of the lack of local interest the culture of oyster was not take up. The Department of Fisheries with the support of the Bay of Bengal (Fisheries) Programme resumed the oyster development work in 1988. Under the programme, the culture of O. folium in Palau Langkawi has been expanded to a larger scale. Another species, Crassostrea iredalei, has also been successfully cultured in Sg. Merchang and K. Setiu, Terengganu. Other potential areas such as Batu Lintang, Kedah, Telaga Nenas and Kg. Teluk, Perak have been identified as suitable for the culture of C. belcheri. The technical feasibility for the culture of C. belcheri, C. iredalei, and O. folium has been demonstrated and extension of oyster culture to the fishing communities is presently being carried out. Oyster culture is presently dependent on natural seed supply. Natural seed supply is however unreliable and often fluctuates from season to season. Artificial seed production technology is being developed by the Universiti Sains Malaysia and seeds of C. belcheri and C. iredalei have already been successfully produced via hatchery techniques.

CULTURE PRACTICES

Oysters comprise the third group of bivalves of commercial importance which are cultured as well as collected from the wild. The on-bottom culture of C. belcheri in Sg. Muar, Johor involves about 20 oyster collectors in an area of about 15–20 hectares. Divers collect the oysters during low tide. The oysters are shucked and the empty shells are thrown back into the river bed to serve as cultch materials. In Batu Lintang, Kedah on-bottom long-lines and surface long-line systems are used for spat collection. Grow-out is carried in trays on surface long-lines and on rafts. The main cultch material is netlon which is used to obtain single oysters. The netlon collector (60 cm × 15 cm) is soaked in mortar (1 cement : 1 lime : 3 sand). In Telaga Nenas and Kg. Teluk, Perak, surface long-line is used for spat collection and grow-out is carried out in trays suspended from the long-lines. Trays (61 cm × 91 cm × 5 cm) for nursery and grow-out are constructed out of netlon material. The raft method is used for the culture of Ostrea folium and polyethylene net panels (2–3 cm mesh) are used as cultches. In Sabah, oyster culture is carried out using the rack and tray system and corrugated asbestos-cement roofing sheets. Spatfall is throughout the year but with two notable peaks. In the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia the 1st peak is from November to January while the 2nd peak is from April-June. In the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia the 1st peak is from January-March and the 2nd peak is from June and August. In Sabah, spatfall first occurs during April-June while a second peak is between October-November. Spat (2–3 cm) removed from cultch materials are usually raised in nursery trays before they are transferred to grow-out trays. Ostrea folium takes up 8–10 months to reach the marketable size of 5–7 cm while C. iredalei and C. belcheri require 12–15 months to reach 10–15 cm. Ostrea folium is sold as shucked meat packed in small plastic bags, while C. belcheri and C. iredalei are sold as shucked meat or shell-on. The main constraints are unreliable natural seed production and unknown quality of the oyster meat produced.

| STATUS | SPECIES |

|---|---|

| C. belcheri, C. iredalei and O. folium | |

| Source of seed | Wild |

| Culture method | Suspended (raft & stake) and bottom (rack) |

| Yield/ha | NA |

| Marketing | Domestic |

| Production area | 30–50 ha |

| Level of culture | Developing |

| Major constraints | Limited seed supply; Uncertain product quality |

SCYLLA SERRATA

HISTORY

Scylla serrata, commonly referred to as the mangrove, green or mud crab can live in a wide range of salinity. There are some brackishwater ponds, especially in Johor ( south of Peninsular Malaysia) which are used for the culture or fattening of the mangrove crab. Floating wooden or bamboo cages are also used in the fattening of crabs, especially in the states of Penang, Selangor and Johor. The mangrove crab has been artificially propagated at the Fisheries Research Institute at Glugor, Penang in the mid 1960s, but the production of young crabs from larval rearing is very poor, mainly due to cannibalism. The fattening of the mangrove crab is based on wild caught, undersized and thin crabs. In 1989, a total of 144 tonnes of mangrove crabs were fattened. The culture expansion of the crab is at present constrained by the lack of stockable young ones, in view of various problems encountered in the hatchery propagation for this species. The Department of Fisheries Malaysia provides various support services, including research and development, extension and training for the development of aquaculture in the country. One of the major aquaculture research and development topics considered essential for the future expansion and promotion of crab seafarming includes the development of an appropriate and cost-effective breeding and culture system. Research has to be carried out on both the hatchery and grow-out phases, covering optimum stocking densities, optimum enclosure designs, etc. As crab culture is an operation that is affected by the often inconsistent supply of natural or wild seeds, research has to be stepped up to the setting up of commercially viable hatcheries.

CULTURE PRACTICES

The mangrove crab is not farmed in the strict sense. They are cultured (shell-hardening) or fattened in floating wooden or bamboo cages with plastic on polystyrofoam drums as floats and because of this only larger crabs nearing maturation size are stocked. Netlon is commonly used for mesh. These operations can be seen at Pulau Ketam (appropriately named “Crab Island”) and at the mouth of the Muar river in Johor State. The supply of crab juveniles totally derives from natural stocks. Some of the growers obtain their seed stock from Thailand. The crabs in Malaysia are fished by using a variety of gears, including hoopnets, baskets, traps, barrier nets, stake nets, gill nets, dragnets and push nets. The mangrove crab has been artificially propagated at the Fisheries Research Institute at Gelugor, Penang in the mid 1960s, but the production of young crabs from larval rearing is very poor, mainly due to cannibalism. A typical cage measures 1.8 m × 1.2 m × 0.6 m. Larger cages of about 3 m3 with a depth of 1 m are also used. The crabs are separated according to sex and about 120 individuals are reared per cage. The carapace width of the crabs range from 7.5 to 18 cm. The crabs are fed chopped trash fish (mud crabs do not accept currently available pelleted feeds) for a period of 2–3 weeks, by which time they would have attained marketable size and condition, while female crabs will have well-developed gonads. The market size is 300 to 500 g, although they may reach 1 kg. A major constraint in this culture is the high mortality as a result of cannibalistic habits. Buyers in Malaysia are importing mud crabs from India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia and Bangladesh. The mud crabs are very hardy and can survive several days out of water if kept moist. The majority of the fattening units are small-capital operations and are operated by family members. This seafarming activity is reported to be an income generating occupation. In view of the rapid developments in the demand and export of this product, there is an urgent need for a concentrated effort to investigate the biology, ecology, etc. aimed at increasing its production.

| STATUS | SPECIES |

|---|---|

| Scylla serrata | |

| Source of seed | Wild |

| Culture method | Floating cages |

| Yield/ha | NA |

| Marketing | Domestic and export |

| Production area | NA |

| Level of culture | Developing |

| Major constraints | High mortality; Limited juvenile supply |

EUCHEUMA spp.

HISTORY

Although Malaysia has an extensive coastline and coastal shelf that supports a prolific growth of many species of seaweeds, the production of seaweeds gathered from the wild is almost negligible. This production is limited to collections by isolated fishermen who then sell the seaweed or prepare them for home consumption. Experimental culture of seaweed have been carried out by the Fisheries Research Institute, Glugor, Penang since 1983. Up to now, there is still no commercial production of seaweed in Peninsular Malaysia. In East Malaysia, research on Eucheuma culture was initiated in Semporna, Sabah in 1986. Both Eucheuma cottoni and Eucheuma spinosum can be gathered from the wild, but only E. cottoni is cultured, mainly for export. There was no export of Eucheuma from Sabah until 1990, when between January to July 1990, 80 tonnes of dried Eucheuma were exported to Denmark. A survey in 1977 reported that in Sabah (East Malaysia), the Balabac Straits, and the areas around Pulau Gaya appeared suitable for Eucheuma culture. There is no industrial production of seaweed or seaweed products in Malaysia. Agar is imported into Malaysia in four main forms, namely, agar strips, bacteriological agar, agar desserts, and flavoured powder mixes. It was reported that as high as 90 % of agar imported for food is in the form of agar strips, while the remaining 10 % is in the powdered or jelly dessert forms. The Department of Statistics, Malaysia, reported the import of seaweed and its products under two categories: (i) seaweed products; and (ii) vegetable saps and extracts, pectic substances, pectinates and pectates, agar-agar and other mucilages.

CULTURE PRACTICES

Sabah and Sarawak are two states in East Malaysia which have a great potential for the culture of Eucheuma. In East Malaysia, research on Eucheuma culture was initiated in Semporna (Sabah) in 1986 by the Department of Fisheries together with four fishermen households. An estimated 1.5 hectares of suitable site was planted with Eucheuma which consisted of 30,000 plants with an average weight of 250– 300 grams per plant. In 1987, the experimental farming of Eucheuma expanded to covered an area of 10 hectares and involving ten fishermen along with their families. The production of the seaweed was 400 tonnes wet weight. The culture methods used included the stake method, the semi-raft and the raft method. In the bottom method (also called the nylonline method), stakes were pegged one metre from each other and a nylon line tied between the stakes. This is a cheap method compare to the others as it is made up of two stakes and a monofilament nylon (No. 200 lbs) 15 metres long. The semi-raft method was applied only in a lagoon area where the depth of the water was 4–8 metres. In this method, stakes were placed on opposite sides of a suitably identified lagoon with floats tied to the mono-line at a depth of 0.9 metre from the water surface. In the raft method monofilament nets with mesh size of approximately 30 cm are attached and stretched to a raft. Constraints to the culture included fish predation (eg. Siganus sp.), epiphytic growth and adverse environmental (salinity, light, temperature, water movement and water depth) conditions which affects the growth rate of the Eucheuma. Difficulty in getting a good market price is also a major problem. Under the Sixth Malaysia Plan (1991–1995), the Fisheries Department will give more emphasis to research on seaweed culture and processing. Malaysia hopes to see the development of seaweed culture on a commercial scale during this Plan period. However, the expertise of the research officers must first be enhanced through training and technical support from various regional and international agencies before this can be realized.

| STATUS | SPECIES |

|---|---|

| Eucheuma cottoni | |

| Source of seed | Wild |

| Culture method | Stake, semi-raft and raft |

| Yield/ha | 40 mt/ha (wet wt) |

| Marketing | Export |

| Production area | 10 |

| Level of culture | Experimental |

| Major constraints | Predation; Epiphytic growth; Poor market price |