* The manuscript has been reproduced as submitted by the author.

I am deeply honored to have been asked to speak to you this morning. Thailand is a country close to my heart where I have always felt welcome - earlier as a representative of the Government of the Philippines, and more recently as Director General of ICRISAT. ICRISAT, as you know, has a global mandate for research on groundnut, a crop of increasing importance in this country. Our scientists are working in close collaboration with Thai scientists to provide advanced lines suited to the conditions of Thailand. Another facet of agricultural development identified for collaboration between us is watershed management.

Allow me, Your Highness, to congratulate the efforts of the Royal Family in its support of the Ministry of Agriculture to provide the hard-working farmers of this country with products and technologies tailored to their needs.

I am also very proud that my long-time friend and colleague Dr RB Singh has been designated Assistant Director-General and Regional Representative of the FAO. Dr Singh and I go way back to the early days of APAARI, and I wholeheartedly congratulate you, old friend, on your well-deserved appointment.

The topic of my address this morning concerns the worst scourge of the new century: hunger. Hunger is unacceptable. It must cease. Man has climbed the highest peaks. He has explored the deepest depths. He has walked on the moon. The human genome has been mapped. Atoms have been split. Technology is becoming ever more sophisticated. Scientific advances abound. But still we are faced with hunger throughout the world. Why is this? What can we do to stop it, once and for all?

It's not that progress in agricultural science has not kept pace with other scientific endeavors. Indeed, some of the most spectacular advances in human history have been accomplished in the field of agriculture.

During the late 60s and 70s, for example, the Green Revolution drew the entire world's attention to the power of new technologies to accelerate agricultural development. Massive famines, considered inevitable by some, were narrowly avoided through the hard work and dedication of international and national researchers working closely with government officials.

This success story remains one of the shining achievements of our time. But the very architects of that revolution cautioned the world not to rest on their laurels. They warned that it would be difficult if not impossible to repeat. While the Green Revolution had bought time, they said, it could not indefinitely postpone the collision course between population growth and food production.

After the initial leap triggered by the Green Revolution, the 70s and 80s witnessed a period of steady but less dramatic progress, as researchers consolidated the gains of the high-yielding varieties by improving resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses, eating quality, and agronomic traits. At the same time, national programs were assisted in improving their extension services to farmers.

With the food problem seemingly under control, the world's attention shifted to other issues such as environmental degradation and social equity. Some people even became suspicious of the Green Revolution, noting that while wealthier farmers with larger, high-quality land holdings and access to inputs were capable of capitalizing on the new technologies, the rural poor were left further behind than ever.

In response, researchers were asked to find ways of using technology to improve equity, decrease gender gaps, and bias benefits toward the poorest of the poor. In many ways these issues were more difficult than the original Green Revolution technologies, and the gains much less dramatic and slower in coming. Despite these initial doubts, however, impacts in these areas are now emerging as substantial and well targeted towards poverty reduction.

At present, many concerned organizations are pinning their hopes on biotechnology and information technology to provide another major jump in production - a jump that might be comparable to the Green Revolution itself. At the same time, there is an increasing realization that with the globalization of agriculture, commodity prices are likely to decline and efficient production will be the key to survival in agriculture, as in other industries. Inefficient producers and production systems will fall by the wayside. The future may well lie in adapting the cropping system to environmental diversity, making the most of the different natural resource endowments of different agro-ecological zones - rather than using costly inputs to change the environment.

It is difficult to overstate the significance of the Green Revolution. If it had not occurred, an extra billion people would be hungry today. It enabled productivity enhancements that doubled global production of wheat and rice, causing prices for these staples to decline by more than 70% in real terms since the 1970s. This global benefit was of special value to the poor, who spend a higher proportion of their incomes on food than do the wealthy.

Even the developed countries benefited handsomely as they adopted and adapted these new plant types to their own temperate-zone environments. The added value of production to the United States, for example was estimated to exceed $3.4 billion from 1970 to 1993.

The astounding impact of the Green Revolution prompted many economists to examine its causes and lessons in detail. A recent study by the Asian Development Bank found that its research-for-development investments have consistently yielded a greater return than direct subsidies to agriculture. Rates of return ranged from 20 to 60% - far more than returns for non-research investments. The ADB also found that by including a research component in their agricultural development projects, their chances of success were significantly enhanced.

Economic studies found that the Green Revolution's benefits extended beyond the lofty objective of feeding the teeming masses of poor. They demonstrated that agricultural development was an engine of economic growth that broadly reduced poverty. Much of the economic surplus generated by increased productivity was being spent on other goods and services - helping developing countries diversify their economies beyond agriculture, and providing spin-offs such as greater accessibility of goods and services like education and health care.

Expressed at the human level, many people who grew up in poor rural households - and here I can speak from the heart because that's where I come from - know that farm families have long viewed increases in farm income as a way to help our children get a better education and a good job in the city, escaping the cycle of rural poverty.

From this mass of evidence, it is clear that investment in agricultural research during the Green Revolution era yielded, and continues to yield, very attractive returns to development investors.

But there is an ironic turn to this story of success. Although the Green Revolution saved the planet from the horrible consequences of mass starvation, its stunning achievements were never fully appreciated by the world community. Unfortunately, without a clear sign of calamity - without corpses - little attention is aroused. The rewards that come to those who prevent tragedy are rarely commensurate with the rewards reaped by those who react to it. The sad events that occurred in New York and Washington last month are proof positive of this understandable but unfortunate side of human nature.

The irony goes even further, because the enhanced productivity combined with protective policies and subsidies contributed to a food glut in the developed countries that caused many living in those fortunate circumstances to think that the world food problem had become one of excess, not shortage.

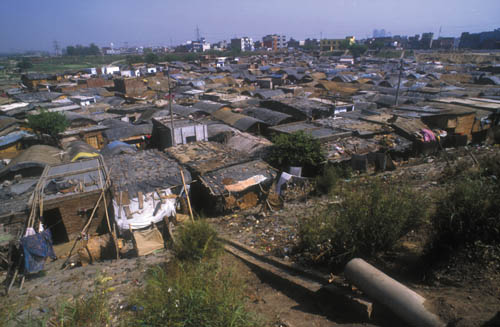

But this was clearly an illusion. Despite the increasing availability of food, 13% of the global population, about 840 million people, are food insecure. Predictably, this food insecurity is concentrated in developing countries, with a regional breakdown led by Asia in both numbers and proportions (48% food insecure), followed by Africa (35%) and Latin America (17%).

The root of this paradox is poverty. The poor simply cannot afford to buy the food they need. Even subsistence farmers must purchase significant portions of their annual food supply. Although the Green Revolution dramatically reduced food prices, huge numbers of poor still live on the edge of despair.

Studies have disagreed on the equity consequences of the Green Revolution. Some argue that it caused the rich to get richer, and the poor poorer. Cases have been reported where modern varieties led to mechanization that displaced labor, and forced smallholders to sell out to larger landowners. But other studies, particularly of rice farmers in the Philippines and wheat farmers in India's Punjab, found the opposite - that employment was stimulated, that economic gains occurred across income levels, that landholdings remained as before, and that add-on economic benefits to rural villages further benefited farm families.

So where are we now? Many subsistence farmers on rainfed lands have yet to benefit from improved varieties. The Green Revolution varieties, bred to respond to good soil fertility, water supply and pest control, were not advantageous under more stressful conditions. A quarter of the world's people and agricultural lands missed the Green Revolution party. In India, for example, a country long associated with the Green Revolution, well over 100 million rural poor still struggle to scratch out a living, almost all of whom live in unfavorable, rainfed areas.

These marginal areas and neglected peoples are the source of rapid population growth and environmental degradation. But these farmers cannot afford to adopt the high-input packages of the Green Revolution, nor would it be environmentally wise for them to adopt these packages even if they could afford them. Much can be learned by striving to understand traditional practices that are by definition based on ecologically friendly principles such as shifting cultivation, intercropping, and tailoring crops and crop management systems to local conditions, instead of trying to suit the environment to the crop.

The wisdom of relative investments in favorable versus marginal environments has been a controversial issue since the mid 80s. The Green Revolution experience taught that more favorable areas generated larger responses to inputs at lower costs per unit output. But partly as a result of the longstanding priority accorded to those favorable areas, many of the readily obtainable gains have already been achieved in these areas. Returns to research in favorable areas are beginning to level off or even decline, as sustainability issues confront some key areas such as the high-yielding rice-wheat systems of the Indo-Gangetic Plain of South Asia.

It should come as no surprise that progress in marginal areas has taken decades to bear fruit. It is often forgotten that the impact of the Green Revolution took 20 years to make itself felt after the initial Ford and Rockefeller investments in short-duration wheat in Mexico. In only a slightly greater time frame, the investments of the CGIAR and its partners in marginal lands have begun to pay off handsomely, despite the greater complexity of the challenges and variability of the environments.

Recent evidence, such as the econometric analysis of district level data in India reported by Fan and Hazell in their seminal 1999 paper, is revealing that carefully targeted investments in marginal areas are delivering comparable or even greater returns than in favored areas. A recent study by the ADB concluded that, and I quote:

Investments in infrastructure, agricultural technology and human capital are now at least as productive in many rainfed areas as in irrigated areas and have a much greater impact on poverty alleviation.

End quote.

Not only cereals, but improved food legume varieties are being enthusiastically adopted in dry marginal areas. Shortening the crop growth cycle by a third or more for pigeonpea and chickpea have enabled farmers to plant these protein-rich pulse crops before or after cereals in South Asia, substantially raising farmers' incomes while diversifying their operations and improving their diets.

The achievements of the Green Revolution also fostered hopes that agricultural development could be more specifically targeted towards the more disadvantaged people within society, particularly women and children. According to a World Health Organization report, women constitute only one-third of the world's work force, yet they work two-thirds of the total hours, for which they receive only 10% of the total income, and own less than 1% of the total property.

Similarly, the adoption of improved groundnut production technology packages significantly increased the use of female hired labor, and helped to provide new income channels through task specialization. For example, the introduction of chickpea in the Barind zone of northwestern Bangladesh provided a new income stream for women who harvest the top twigs for consumption as a fresh vegetable.

It is hardly surprising that women also highly value reductions in drudgery and occupational hazards, in addition to enhanced income. Asked what she would do with the extra income chickpea cultivation had brought to her family, one Bangadeshi woman replied that she would now be able to send her daughter to school. Previously only her sons were allowed to go. This illustrates the need to take a broader view of poverty than the simplistic view of economic advancement.

The broadening of the international agricultural research centers' agenda during the late 80s and 90s put major strains on its capacity to deliver. Funding had not increased in proportion to expectations, and many thought that the System's reach now exceeded its grasp.

The same pressures befell national research programs. As it became clear that no single organization could fully address the complexity of the new agenda, these international and national organizations realized that they would have to greatly expand their partnerships.

As a result, partnerships among all sorts of organizations - international and national, public and private, governmental and non-governmental - grew rapidly in number, diversity, and scope. Steadily, the array of institutions engaged in agricultural research and development interlinked themselves in an ever-tighter fabric of partnerships.

The closest partners of the CGIAR Centers have always been the government research and development agencies responsible for agriculture. Increasingly, however, collaborative arrangements with NGOs and the private sector are emerging. Such collaborative activities frequently have comparative advantages for strategic or applied research. Being closely focused on near-term impact, these new partners are helping us and our national colleagues translate our findings quickly into impact on the ground. It's a symbiotic relationship - they depend on research organizations as a source of new technologies, and we depend on them to tailor these to local needs. Significantly, NGOs and private companies are well positioned to provide us with farmer feedback.

An excellent example of the dynamism of such partnerships is the success of recent collaboration between ICRISAT and Indian hybrid seed companies. Several companies are now contributing funds to ICRISAT's applied plant breeding work, without any intellectual property or germplasm restrictions and without constraining the research priority set. They have come to realize that 'a rising tide lifts all boats' - that they, as well as others, stand to gain from advances in public-sector knowledge and genetic materials. Our sister Centers CIAT and CIMMYT have garnered similar support from the private sector in Latin America.

The amounts of these contributions are modest, and do not come close to replacing public sector investments. But that's not the point. We view these tangible signs as an important vote of confidence in these partnerships, and such confidence bodes well for the future of agricultural research.

But let's not get overly optimistic. Between 1980 and 1990, according to IFPRI, the International Food Policy Research Institute, agricultural development investment as a percentage of total world development assistance fell from 20% to 14%, and has continued to decline since then. Ordinary people in developed countries, once alarmed by the specter of global famine and the haunting, skeletal faces of starving babies on their TV screens, have now become inured to these images.

This is understandable, but the policymakers of developed countries need to realize that the spillover benefits to their own agricultural prosperity derived from research conducted in the developing world have far exceeded their investments. The givers have got their own back many times over. And far from posing a competitive threat, by helping the poor escape poverty they have created vast new markets for their own exports.

Developing countries are equally guilty. During the period 1981-85, the Australian social observer Derek Tribe estimated that developing countries invested only about 0.41% of the value of their agricultural gross domestic product in research, less than a fourth of the average 2% investment made by developed countries.

To rekindle the fire of the Green Revolution, we need to articulate in modern, compelling terms the best-kept secret of the enormous benefit the world has enjoyed from its investments in agricultural research. The message we must convey is that because we all live in an interconnected world, investments in development protect us all from the suffering, strife, terrorism and pollution that command the public's attention today.

The Green Revolution raised expectations for a continued flow of scientific miracles. This legacy frames the challenge for today's generation of dedicated research and development professionals. What are our chances?

The promise of biotechnology to increase crop and animal productivity while reducing losses caused by pests and diseases is enormous. Massive problems such as drought, voracious insects, physiological inefficiencies, and disease resistance breakdowns no longer seem as intractable as they once were.

The potential impacts of biotechnology are huge. But the challenges are not only biological - they are also institutional, financial, and even legal. But there is little doubt that the proper use of biotechnological tools can add further productivity gains while protecting the environment, as long as it is directed toward the public good.

Many patents are now being issued restricting public-sector access to such fundamental research knowledge as genes and laboratory methodologies for gene manipulation. These patents are equally restrictive toward the orphan crops of the poor. These technologies need to be made available so that public-sector organizations can use them to deliver their promise to the poor.

A key role for international centers is to serve as facilitators - brokers if you like - who can negotiate appropriate arrangements between the public and private sectors as we navigate the road ahead. The international agricultural centers, independent as they are of political or profit motives, have proven their effectiveness as catalysts in such partnerships.

The global revolution in information and communication technology holds equally dazzling potential. The complex, system-oriented solutions required of today's agricultural research are more knowledge-intensive than the simpler seed-centered technologies that drove the Green Revolution.

In the Green Revolution model, it was necessary to provide large amounts of costly inputs to homogenize the agro-environment so as to remove all constraints to yield potential. In the new era, global competitiveness and production efficiency will become paramount. Information will become a key strategic resource, enabling farmers to better tailor their crops and management to their particular locales and conditions, extracting the most efficient use of the endowment they have at hand.

Extension or farmer organizations, even in remote villages, are now able to dial up the Internet over the telephone to obtain information on input and crop commodity prices, seed availability, weather, management recommendations, pest and disease epidemic forecasts, and other valuable insights.

The same channels can be used by farmers to feed back their own observations and knowledge so that researchers, policy makers and the press will have a better understanding of realities on the ground. It will no longer be possible for governments to ignore the rural poor simply because of their geographic isolation.

Better communications will lead to stronger partnerships among research and development organizations. Virtual teams will be quickly formed through searches over the Internet, finding just the right expertise for important problems. They will meet by videoconference to share experiences, consult additional specialists, and view field situations. Just as quickly as they were formed, these teams will disband once the problem is solved, free to move on to other challenges and teams, amplifying the social benefits derived from their skills.

It is not surprising that an achievement as marvelous as the Green Revolution resulted in such diverse and far-reaching outcomes as those I have described. But its ramifications continue to affect the lives of people all over the globe to this day. Surpassing the expectations of most, while falling short of the broad social goals of some, it remains a phenomenon held in both awe and controversy. Nevertheless, all will agree that it serves as a potent example of science in service of development - which we at ICRISAT call Science with a Human Face.

The Green Revolution bought precious time for our global village - an opportunity to bring population and environmental deterioration under control before they outrace our capacity to increase food supplies. This precious interval has enabled scientists to develop even more powerful tools that many believe will unleash a second Green Revolution - a revolution that employs all the tools at our disposal, including biotechnology and information/communication technologies - a revolution that turns grey to green, the Grey-to-Green Revolution for the dry tropics of the world.

If we do our job well, the result will be a more just, prosperous and equitable world - a world with the wisdom and resources to tame the monsters of overpopulation and environmental degradation. If we are successful in our endeavor, the fruits of the Green Revolution will comprise a harvest richer than we had ever dreamed.

Thank you.