Karsten Lundsby

Nordic Agricultural Academy, Rugårdsvej 286

5210 Odense NV, Denmark

E-mail: [email protected]

Summary

Agricultural professionals from developing countries in the experience of the Nordic Agricultural Academy, do not come to Denmark motivated by knowledge of the Danish Farmers' Associations, the farmer-operated Advisory System, the Co-operative Movement or the Danish Folk High Schools, but because they have seen Danish Agricultural Products on shop-shelves all over the World. The Nordic Agricultural Academy runs regular courses that are multi-national as well as tailormade, which have the curriculum developed together with the project(s). The emphasis is on practical application and what works while textbooks and libraries playing referral roles.

Key words: Training, agriculture, management, systems, knowledge, professionals

Introduction: Why study agricultural subjects in Denmark?

Over the last decade, I have answered hundreds and hundreds of letters from people in developing countries, who wanted to come to Denmark in order to study agriculture. Most of them were applying directly for admission to one of our courses related to agricultural management subjects at Nordic Agricultural College (now: Academy), but also a fairly large number were young people who wanted a Farmer's Education, and a similar number were university graduates, wanting to pursue further studies.

Very many times - typically on cold, wet and windy November days - I have asked myself, “why do these people want to come to this inhospitable climate, with its reserved and stressed people, in order to study agricultural systems, which can in no way be transferred to their own countries, neither the crops, nor the animals, nor the technologies?”

And gradually I have realized that however unique our Farmers' Associations may be, or our farmer-operated Advisory System, our Co-operative Movement, or our Folk High Schools, and however world-famous we may consider ourselves for these very achievements - they are not the reasons for these applicants. For when some of these applicants succeeded in coming to our courses, and we then told them about these characteristic features - they did not know at all! And they got very surprised by what they learned. So again I asked myself, “Why Denmark, of all places?”

But gradually I realized that all of these students have known one or more agricultural products from Denmark. So most likely their line of reasoning has been:

“If I can go and study agriculture in that small country, which is nevertheless able to place its agricultural products, at high prices, on shop-shelves all over the world - there must be something valuable for me to learn!”

Incidentally this conclusion also gives an answer to another frequently asked question, which is posed by many Danes, even by a number of development workers:

“Why take these people all the way to Denmark to show them farming which cannot be used in their own countries, where they grow rice or maize, and where they do not eat pigs? It would be much cheaper to send a few trainers there, in order to work with them based on their own actual farming, and in order to tell them how it could be improved.”

So let me summarize the reasoning of these students:

Then it will be their own challenge to translate this knowledge to the conditions in their home countries.

Capacity building

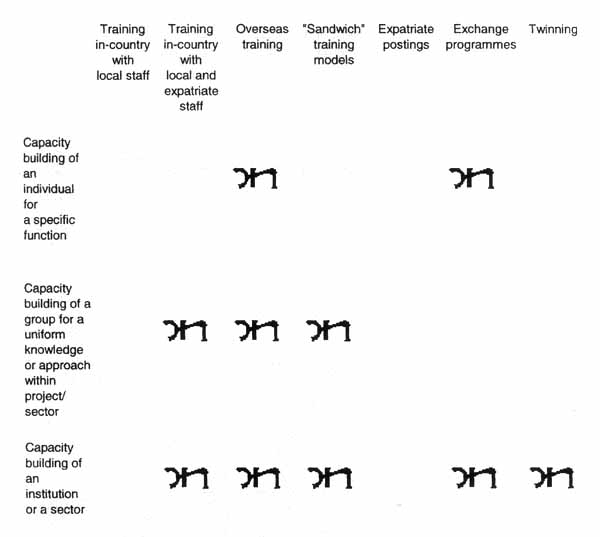

The concept of capacity building could be viewed as in table 1, in which is indicated those fields in which Nordic Agricultural Academy is or has been active.

Table 1. Capacity building. Activities of Nordic Agricultural Academy

Nordic Agricultural Academy

Formerly Nordic Agricultural College in Odense was up till 01.01.1999 an independent self-governing institution. From that day it amalgamated with Tietgen Business College, also in Odense, and it is now one of the five business centres of the new, joint institution. Nordic Agricultural Academy (NAA) is still continuing to offer agricultural management education in two different lines, with an equal emphasis, namely through a Danish Department and an International Department.

The Danish Department is part of the Danish vocational education system, and young farmers who have got a theoretical foundation and a practical experience through the Farm Managers' education (a total of 4½-years), can proceed for two years' additional education where they, if successful, will graduate and achieve an Advanced Diploma. The education will give them a more comprehensive understanding of farm economics and general economics, farm management and general management, commerce, communication, computers, and languages. (The language of instruction is Danish).

Together with holders of Advanced Diplomas from other related studies, e.g. dairy, food technology, fishery, our graduates can also continue for another 1½ year, studying languages, international trade and legislation, marketing, and project management. They will then graduate as Food Business Engineers, which in comparison will rank just above a bachelor's level. (The language of instruction is Danish).

The International Department is offering both regular courses, and tailor-made courses, conducted in English, with various agriculture-related specializations, and at various levels.

Regular courses

The main courses in this category have been:

Management in the Agricultural Sector (3 months)

Agricultural Extension Co-ordination (17 weeks)

Soil Fertility Management (11 weeks) - in collaboration with The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Danish Institute of Agricultural Sciences, and Bygholm Agricultural School.

These courses, which we conduct for Danida, are open courses in the sense that students from different countries and with a certain span in their occupations will participate in the same course.

But the courses will be closed courses in the sense that they will be offered only to students who work in

countries with Danida priority and within

sectors with Danida priority, or

projects carried out by Danish NGOs, partly financed by Danida

projects carried out by Danish companies, who have a prior agreement with Danida.

The system is that Danida's Fellowship Programme will issue an annual catalogue, and the local Danish Embassies will invite relevant Ministries, Government agencies, NGOs, and projects to submit names of candidates for a specific number of places at the courses, and Danida will make the selection on the basis of these names.

Tailor-made courses

Examples of such courses are:

These courses are developed and conducted specifically for one project, one sector, one Ministry, etc. in one country.

Courses have been made for e.g.

The course contents and course duration are agreed upon between the client, the local Embassy and NAA and a request for funding is then forwarded to Danida through the Embassy.

In most cases the courses are developed after a fact-finding visit to the project. In a few cases the sequence has been that a course proposal has been developed based on ideas and an outline from the Project Management, followed by a factfinding visit and discussions in the country of the activity.

Approach

An attempt at summarizing the approach in our international courses could be:

“Participatory, application oriented learning”

This implies, that

We try to take our starting point in the background and the training needs of the participants.

Based on small cases which we have developed, and which all have a setting in developing countries, we use the resources and various experiences of the participants to arrive at the general theories and principles; textbooks are also used, but mainly for reference or further reading.

Exercises are also widely used in order to encourage discussions, where the participants can test their competences, and arrive at an understanding of the fact that within our subjects of management and extension, there is not just one true answer.

Exchange of experience among the participants and between the tutors and the participants is given much emphasis in order to eliminate habitual thinking, and many discussions take place, aiming at sharpening the critical judgement of the participants.

When exams are used, they are application oriented (all books and notes are allowed), not memory-oriented.

Exposure is reached through an excursion programme, mostly combined with a practical period at a school-farm or/and working visits with agricultural advisers. The aim of this is primarily to demonstrate how the management information systems actually function in practice, and how the theories and systems which we talk about in class, are actually functioning in reality.

In almost all courses, the participants work out their own individual project, in which they take a problem from their own daily work, analyse it, propose a solution to it, and draft a proposal for a project, plus a strategy for its implementation.

In the co-operation between the student and her/his tutor, it is the student who is supposed to be the subject specialist, whereas the tutor helps with analysis, structuring, formulation, principles, and methods.

Cases

Based on an evaluation report from one of the consulting companies, Danida Fellowship Centre (DFC) wanted us to develop a 3-months' course called “Management in the Agricultural Sector” (MAS), which should be offered through the catalogue, and run 3 times. The target group was “Managerial staff from agriculture-related businesses, marketing services or projects”. Since it was a Danidaowned course, NAA worked out a draft curriculum, which was then adjusted by Danida Fellowship Centre staff, and by an external consultant who they hired for that purpose. At the selection of candidates for the course, it turned out that not a single applicant from the original target group was present - all applicants were from middle-level or lower middle-level management, or just hopefuls. The course was run the first year according to the agreed curriculum and time allocations, but DFC's assumptions in terms of prior knowledge, management experience, and decision making power had to be adjusted in a downward direction.

In the course evaluation report we suggested a number of changes in the curriculum and the time allocations, and these were implemented when the second course was run. No further changes were needed for the third course.

A number of students from Danida's 3 projects for Women Agricultural Advisers in India (WYTEP, TANWA, and TEWA), who had attended our former 9-months' course, had been gathered at the Embassy in New Delhi for a de-briefing and an evaluation of the course, and the report from that meeting was sent to us at NAA. In response we drafted a 6-month course, called “Agricultural Management and Extension” (AME), which was intended to meet the more specific needs of these projects. Some months later the three Advisers in charge of the projects visited Danida, and we had the chance to discuss our proposal with them, and make some modifications, after which the course was in principle approved. It was also agreed that I should visit the projects before the course was given the final touch, and in order to get some back-ground from which cases and materials could be developed. So when the Course Manager had been identified, NAA sent the two of us to India for two weeks, where we visited the projects, did field visits in order to see on-going project activities and talk with beneficiaries, we interviewed former as well as prospective students, and held discussions with the Advisers as well as with the Embassy staff. The first course was run in 1994, and only very minor changes were made in the curriculum before the next course. In April we are starting the 6th course, and the curriculum is still basically the same, but of course a lot of new materials have been developed, and approaches have been modified over the years.

In 1995 the family of projects with Women Agricultural Advisers in India had been expanded with a new member - MAPWA in Madhya Pradesh, and their Danida Adviser had visited NAA during the summer. In 1996 I decided to treat myself to a holiday in India, which would primarily consist of visiting former students privately, and in satisfying my curiosity and interest about life in rural India. In that connection I also visited MAPWA, got the chance to meet all the (small) staff, as well as meeting Department and University Staff, and informing them about our training activities in Odense. And I had very long discussions with the Danida adviser about how she could utilize our course to the optimum.

These discussions were continued in 1998 - after the first two MAPWA-students had attended the course in Denmark - when I visited MP again, this time on a study tour. And we were able to make a co-ordinated plan for the Individual Projects of those 5 persons from MAPWA, who we envisaged would be coming to NAA that year. In this plan we considered both the positions and the preferences of the prospective students, as well as the development perspective for the project. And when the students arrived at NAA, I was the tutor for most of them.

Experiences

Evaluations and follow-ups

For some reason or other, the evaluations at Performance Level of the courses, which we have been conducting, has been very scanty at the formal level.

Only in 1995 a fairly comprehensive evaluation was carried out by a firm of consultants, dealing with all the management courses, which were conducted under Danida's Fellowship Scheme - including our former 9-months course. The main conclusion was that a much shorter and more focused course might give an equal impact on the participant's projects and organizations. This is reflected in the design of our courses after that time, but no further formal evaluations have been undertaken.

At the more informal level, staff from Danida Fellowship Centre has visited some of our former students in various connections. And from Chief Technical Advisers and Sector Support Programmes we get occasional comments.

And finally NAA has on its own initiative conducted two follow-ups, one in Africa in relation to the former 9-months course, and one in India (Orissa) in relation to the 6-months AME-course.

The main conclusion of the follow-up in Africa was that the majority of the students felt that the working relationship with their superiors had been influenced much after attending the course. Typical examples were that the students had gained confidence, had earned respect, were being listened to, and were given more responsibility.

Also the working relationships with colleagues and counterparts, as well as with subordinates, had been somewhat influenced in a positive direction. About two thirds of the former students had fully or partly implemented their Individual Application Projects, and most of them had used the same technique in solving other problems.

From the follow-up in India in 1996, the report says:

Implementation support

As a new facility, an Implementation Support has been offered in connection with the course in Soil Fertility Management, which we held in 1998. The idea is that when the participants have returned to their respective jobs, they will first of all be able to draw on the expertise of their lecturers and tutors in relation to technical questions for a period of half a year. Secondly it is envisaged that if a sufficient number of participants in one country or region encounter problems in the implementation of their Individual Implementation Projects, a staff-member from NAA will visit them, in order to discuss the project and the problems with themselves and with their superiors. The idea behind this is of course to demonstrate that Danida and NAA are concerned with the former students and their projects, thereby providing some leverage to the implementation of the projects.

The present position is that none have requested technical support from us. As for the implementation of the Individual Application Projects, we do not have a large number of replies to our enquiries, but those, which we have; indicate that the projects are under way on a small scale - especially the no-cost components. Lack of any kind of funding is the most severe obstacle, but some are hopeful that they may get some funds in next year's budget.

Conclusion

From the point of view of Capacity Building, the regular courses have their particular strength in the fact that they are multi-national, and therefore the participants will come home with a knowledge about “how they do in Denmark”, but they will also know about several other - and often more relevant - cultures, organizational cultures, and administrative systems. And since we often see that the same projects are sending participants to our courses year after year, we reckon that this way of gradual shaping of an organization towards more knowledge and towards more open-mindedness, is one effective way of building capacity.

With the tailor-made courses the effects are more clear, and better known to us, since we maintain contact with the projects afterwards - and sometimes the courses are repeated too. Since we have done our field work in advance, and have developed the curriculum together with the project(s), we know that these courses have their impact on the organizations not only through the added (and common) knowledge of the participants, but also through a team-spirit, and a synchronized way of handling problems and new situations. And to larger projects, that effect is probably more valuable than the multi-national exposure and exchange of experiences, which takes place in the regular courses.

And to come back to my starting point about why to study agricultural subjects in Denmark, my own answer would be “because we are not only talking theory, we are also dealing with practical application, and we are able to show that what we are talking about, actually also works!!”

APPENDIX 1: Example of a regular course

Management in the Agricultural Sector

Course objectives

To give the participants a thorough theoretical and practical knowledge, which will enable them to identify, plan, and introduce efficient and effective management systems in an agricultural Organization, based upon an understanding of modern management theories. The aim of the course is specifically NOT to teach “modern agricultural practices”, but to go deep into an analysis of the presently employed systems within a sub-sector, a project or an enterprise, with the aim of revealing weak points and scope for improvement, and thereby creating a basis for introduction of planned changes.

Course participants

Managerial level staff from the agricultural sector (Ministry, Ago-business or NGOs), or experienced advisers from the sector. Participants hold a Bachelor Degree in agriculture or a related subject; have 2 years of relevant experience, and a good command of English.

Contents:

| 1. | Introduction | 25 |

| Introduction to Denmark (10), Danida orientation course (15) | ||

| 2. | Management tools | 135 |

| Business reports: Generation and registration of management information (15), Processing of the information (15), Accounts and Financial Statements (20), Planning and dimensioning techniques (20). Communicative Knowledge and Skills: Communication theory / role of culture & gender in communication (20), Marketing (15), Training interventions (15). Logical Framework Approach (15). | ||

| 3. | Management techniques | 90 |

| Monitoring and control (15), Analysis of critical points in management's reports: (Projects/ Input supply/ Marketing/ Agricultural credit) (25), Analysis of the Organization: Organisational theory (20), Human resource management (15), Strategic Management (SWOT-analysis/Strategic choice) (15). | ||

| 4. | Individual Project writing techniques | 45 |

| Logical Problem Analysis (10), The writing process (classes and exercises) (15), Word processing on the PC (20), Consultations and Presentation of Individual Projects. | ||

| 5. | Exposure | 55 |

| Placements/Excursions. | ||

APPENDIX 2: Example of a tailor made course

Agricultural Management and Extension

Course Objectives

To give the participants the necessary knowledge and skills to enable them to work out solutions to farming problems, and to plan and implement agricultural extension and training programmes, as well as efforts directed towards income-generation, for small scale farmwomen in their home states in India.

Course participants

Women Extension Officers from Danida's Agricultural Advisory projects in India (WYTEP, TANWA, TEWA, MAPWA). Participants hold a Diploma (or higher) in Agriculture or a related subject; have some years of practical experience from extension work, and a good command of English

Contents:

| 1. | Introduction | 65 |

| Denmark, farming and advisory system (30), Danida orientation course (35) | ||

| 2. | Educational subjects | 130 |

| Extension systems and extension work (50), Training adults (40), AV-communication option (20), Word processing option (20). | ||

| 3. | Social subjects | 70 |

| Gender & development (40), Leading groups (30). | ||

| 4. | Agricultural Management subjects | 260 |

| Animal husbandry (40), Crop husbandry (40), Horticulture (30), Farming systems and agroforestry (60), Biological farming systems (40), Environment and ecology (30), Animal husbandry option or Crop husbandry option (20). | ||

| 5. | 5. Auxiliary subjects | 70 |

| Project Management (30), Basic agricultural economics (40). | ||

| 6. | Exposure | 315 |

| Practicals at farms (210), Practicals with advisors (15), Excursions (90). | ||

| 7. | Individual project writing | 20 |

| The writing process (15), Consultations and presentation (5) | ||

C.E.S. Larsen and J. Madsen

The Royal veterinary and Agricultural University

Department of Animal Science and Animal Health

2 Groennegaardsvej, 1870 Frederiksberg, Denmark

E-mail: [email protected] and [email protected]

Summary

Human capacity building (HCB) is understood as improvement of a person's individual skills, which are directly or indirectly linked to the person's professional life. HCB is something that primarily happens within the person and the outside environment can only facilitate and stimulate the capacity building process. This places the trainee at the centre and the teacher as a facilitator.

HCB activities should be structured starting with a need assessment of the institution followed by an open procedure for selecting candidates. The selection of candidates may easily be influenced by irrelevant factors if it does not follow certain criteria. It is proposed that a three-step model be used in the selection of candidates to secure that 1) the perspectives of the institution are considered 2) the motivation of the selected candidates is high and 3) the ability of the candidates to gain from the training is considered.

There are advantages and disadvantages with training in the home country and overseas. These are to be seen from the perspective of the employer (home institution), the individual trainee and the host institution and eventually the donor. It is not possible to make general guidelines for the choice of home or overseas institution. There are professional and personal advantages as well as disadvantages in overseas training, but one thing is sure. It is more expensive. It has been common to combine the local and overseas training in the so-called “Sandwich model” which try to include the best components from the two options. Moreover, training by short-term visiting overseas teachers (both in the North and in the South) proves to inspire the trainees/students.

Key words: Human, capacity, building, training, needs, assessment, animal husbandry

Introduction

Human capacity building (HCB) has always been an issue. Progress ever since the Stone Age has relied on mans ability to increase skills and knowledge. Education is a cornerstone in any country's attempt to progress and the whole concept of HCB has attained increased focus during the last two decades. In that respect Tropical Animal Husbandry is no exception to the general trend.

The aim of this paper is to elaborate on what is needed for a HCB effort to be worthwhile. It starts with some thoughts on how to identify the right individuals to provide some kind of formalised training; the model presented should have universal relevance. The second part of this paper looks at potential consequences of different training strategies for trainees from The Third World.

The aim of the paper is to raise the reader's awareness of the processes that influences the selection of trainees, the potential consequences of different training location strategies and the impact of the scientific view in training on our ability to tackle tomorrow's problems within tropical animal husbandry. This paper mainly deals with the part of HCB that is achieved through formal training. However, the paper won't look at specific training and education possibilities but solely deal with the issue of HCB within Tropical Animal Husbandry on a more theoretical level.

The concept of HCB

Lets start with defining how the concept of HCB is understood in this paper. HCB is in this paper understood as, any conscious attempt to improve the individual skills of a person, skills that are directly or indirectly linked to this person's professional life. When talking about HCB one has a tendency to think mainly of institutionalised training and education events in the form of formal courses. However, a substantial part of a person's capacity building happens outside the classroom. It is human nature to experiment and a lot of our individual knowledge and skills are achieved through ‘try and error’ or ‘learning by doing’ in our everyday life. HCB is a life long journey. No one can truly say that they are fully educated; there will always be new things to learn.

Here HCB is defined as something that primarily happens within, it can not be imposed from the outside. It is a common misunderstanding that a person can be developed, or that training is a passive process where the instructor just pours knowledge into the receiving pupils. The outside environment can only facilitate and stimulate the individual capacity building process, it is wrong to think it can impose it. This is an important point for the way of approaching the concept of HCB in this paper. It places the trainee right in the centre of focus, and turns the aim of the training session and the instructor into a facilitating role aiming at creating an enabling an inspiring environment for learning.

Selecting the right person

Developing a model

Since the trainee is placed in the centre of our focus it might be worthwhile trying to develop a model, which can aid in identifying the right individual to offer training in a given situation. The model should be useful both for individuals interested in participating in a training event and for people and institutions involved in identifying the participants. The model presented here has been labelled a Trainee Identification Model'. It is by no means a full fledged model, but more a first step of structuring some thoughts and discussions on the issues: What is it, that determine that an individual venture into a structured HCB process? How can one ensure that a given HCB event becomes a success? Not only for the individual but also for the institutions this individual works for, and for the field they work within.

Modelling of thoughts is not easy. The contradicting problem with models is, that they to some extent have to be context independent in order to be generally valid, but the more general they are, the less precise they become when applied to a real situation. This model has therefor as any other model a limited area of relevance, which we will try to define in the following.

From the institutional perspective the model can be used during long-term strategic planning or in short/medium term management in cases the institution gets relatively sudden assess to resources for capacity building. From the individual point of view the model can be used during long-term career planing or as a decision tool when one is offered a training opportunity.

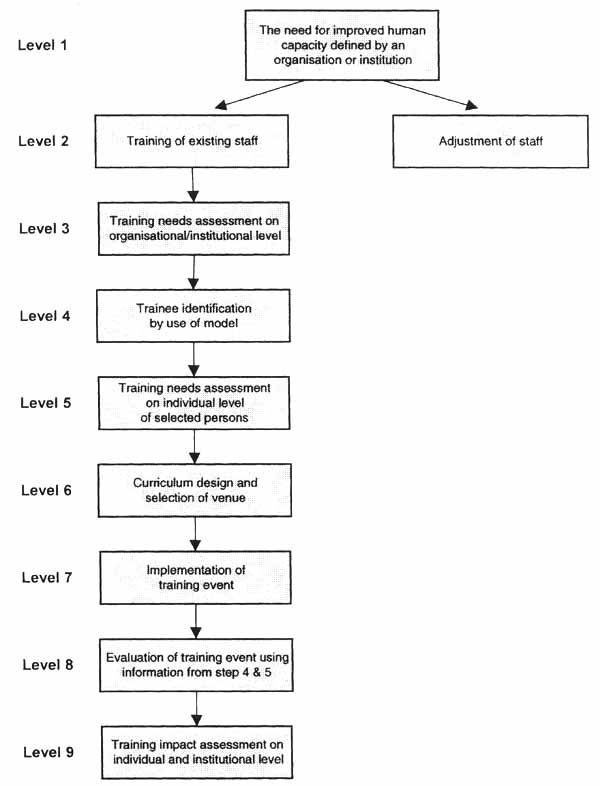

A HCB event follows a natural development from ‘cradle to grave’ which can be split into different sequences or levels that follows each other as it is illustrated in Figure 1. The trainee identification model', which is sketched in this paper, fit in the first half (level 3 and 4) of the process of enhancing human capacity as it is illustrated in Figure 1. Other tools and models developed to aid the training process concentrate more on the later part of a training event. To our knowledge there has not been much focus on developing more standardised procedures for selecting the most relevant candidates within a given setting, or tools that are also useful for the potential candidates themselves.

The model developed here consists of three sub-models; one deals with the context the potential individuals are operating in; while two and three deals with the potential individuals, two with their level of motivation and three with their level of abilities. The aim of sub-model one is to guide the process of identifying potential candidates to send for capacity upgrading within the organisation. By using the model the organisation will be forced to assess the personality's accessibility. Persons who want training can also use sub-model 1 to identify what factors influence their possibilities for being selected in a positive/negative way. The aim of sub-model two is to get a picture of what factors influence the individual's motivation for venturing into training positively as well as negatively. Sub-model three, which uses some aspects of traditional ‘training needs assessment’ models, aim at getting a clearer picture of the individual skills and abilities. The aim is to see how well the persons' qualification corresponds to the institutions/organisations needs. Moreover, an ability assessment of the participants gives useful information on which the forthcoming training should be partly based.

Figure 1. The natural sequences of activities in a formalised human capacity enhancement event

Sub-model one: The individual's accessibility/possibilities

The institutional perspective

A given organisation/institution/project has identified that they need to enhance their human capacity, and has chosen to do it through an upgrading of selected parts of the existing staff (level 1 and 2 in Figure 1). Now the aim for the institution is to select the right persons to upgrade. The first step in this process is to identify where in the organisation the improved capacity is needed, on what organisational level it is most suited, what the institutions existing human capacity is with relevance for the identified target area. This process is normally closely inter-linked with the fact that the institution has become aware that it has insufficient human capacity. Even when the identification and selection of trainees is quiet obvious, either because the number of potential candidates is small or because the capacity building is earmarked for specific persons, using the model might prove to be beneficial.

The first part of the ‘Training Identification Model’ consists of the ‘Accessibility Level Assessment’ as illustrated in figure 2. The assessment model consists of three areas or clusters of focus: options, time and money, respectively. The heading ‘options’ stands for the person's internal position, organisational as well as social, level of responsibility, work performance, educational background etc. Time, refers to the likelihood of finding replacement during training, how essential the person's presence is for the organisation and private matters that influence the person's availability. Resources is of course mainly a financial aspect. Based on an organisational appraisal potential candidates are plotted into the model. The model is then interpreted in the way, that the more overlapping the answers are the higher the level of accessibility of the given candidate. The graphic picture, which will emerge from the analysis of the answers, should then aid the organisation in selecting candidates for interviews.

Looking at Figure 2 it is obvious that person ‘D’ is the most accessible, that person ‘A’ and ‘B’ are not the right persons to recommend for HCB and that person ‘C’ is a potential candidate if the time issue can be resolved.

Through such a structured selection process, the organisation will have to prioritise whom they want to recommend for training and thereby make consideration regarding the possibilities for releasing manpower and the consequence of such a decision. Moreover, since it is the organisation's own prioritisation the process of releasing the person for training will be facilitated internally and it will ensure a proper utilisation of the improved human capacity, once returned. A standardised, more open procedure, which aims at bringing more that one candidate forward for further selection, should be a potential counter measurement to fraud. It is no secret, that nepotism and corruption are often uninvited guests at selection procedures. How much influence those factors have varies according to institution; country; type, length and location of training etc. It is not within the mandate of this paper to deal with ways to tackle this issue.

Figure 2. The Accessibility/Possibility Level Assessment model (sub-model one)

The individual perspective

An individual can use the model to get an overview over how likely it is that she will be selected for formalised capacity building. If the likelihood is small and the interest high then using the model might give an indication on future career moves which will increase the chances of a continued HCB.

Sub-model two: The individual's level of motivation

Since HCB is something that happens within the individual, it might be worthwhile looking a bit on what factors influence the individual's motivation to spend resources (energy, time and money) on capacity building. It is no big secret that a highly motivated person gains more from a given training session than an equally gifted person with lover motivation does. Figure 3 is a list of some of the factors that might influence a person's motivation level.

It is obvious that there is a whole range of factors affecting the individual's motivation to go into a formalised capacity building process. The list in figure 3 is by no means exhaustive, and few people are consciously aware of which factors that influences them. In figure 4, the factors, which were listed in figure 3 are clustered into three groups to form a model over the main categories of factors affecting a person's motivation level. The three groups are labelled curiosity, prestige and security, respectively.

Figure 3. Factors influencing the individual's level of motivation for venturing into a formalised training event. (What you see here is a young African girl, Microsoft just dilute our vision…)

Figure 4. The Motivation Level Assessment model (sub-model two)

Based on a questionnaire the applicant's level of motivation can then be accessed and the result plotted into the model. The model is then interpreted in the way, that the more overlapping the answers are the higher the level of motivation. The graphic picture, which will emerge from the analysis of the answers, can then form part of the base for an interview with an applicant or help a person to put focus on why the level of motivation is low.

Sub-model three: The individual's abilities

Although motivation is a crucial pre-requisite for HCB, the ‘Motivation Level Assessment’ is not enough to ensure successful capacity building through formalised training. As in most ‘Training Need Assessments Models’ the individual's abilities has to be appraised before any HCB process is initiated. This ‘Ability Level Assessment’ forms the third part in our attempt to build a comprehensive ‘Trainee Identification Model’. The ‘Ability Level Assessment’ focuses on abilities of direct relevance for the HCB, which the organisation has identified it needs (‘Level 1.’ in Figure 1.). That means that the ability level assessment is targeted for a specific purpose, not a general staff assessment.

In figure 5 an ‘Ability Level Assessment’ model has been sketched after the same principles as the earlier sub-models. The three crucial factors to look at when assessing an individual's ability to undergo formalised training as part of a HCB process are: The level of knowledge, the level of experience and the methodology used to operationalise the current knowledge. Knowledge is understood as any kind of wisdom and common sense obtained through formalised and non-formalised training. Experience is also broadly understood as a concept. It is not only confined to the experience obtained through years of service but also by other activities. ‘Methodology’ covers the different tools that the person uses to operationalise the knowledge: it can be statistics packages, survey techniques, planning and management tools, etc, etc. The way of assessing person's abilities to undergo a formal HCB process can be made following the same path as indicated in the ‘Motivation Level Assessment’.

Figure 5. The Ability Level Assessment model (sub-model three)

Once the candidates have been plotted on to the model, the organisation in collaboration with other stakeholders has to decide whom to select. Here the most obvious choices might not be the ones in the very centre of the model, which represent candidates with very high abilities. Staff members, who have all abilities, although not on the required level, might not need extra formal training. Maybe it is more relevant and/or cost efficient to boost their human capacity on the job e.g. by changing their job descriptions or organisational placement.

It is often seen that well functioning and highly qualified senior staff is selected for formal education on M.Sc. or Ph.D. level. The reasoning for choosing this staff group might be based on arguments like: ‘they have served the institution for many years’, ‘it is their turn’, ‘they missed the opportunity earlier’, etc. The benefit of such a prioritisation for the employer can be questioned. Other ways of recognising a senior staff member than using scarce external training funds might be more longterm beneficial for the organisation. In the next chapter we will look into what kind of forces and hidden agendas have an impact on the selection procedures when we speak of overseas training.

The next step

If the concept works, then by using the ‘Trainee Identification Model’ one should by now have identified, not only all potential trainees, but also been able to select the most motivated and skilled ones. By going through the different processes in the model the institutional as well as individual self-awareness on HCB, will unavoidable have been raise. This again will facilitate the entire HCB process.

Knowing the organisation training needs and the trainee's individual level of motivation and abilities are quit crucial for the success of a formalised HCB process. This information will give the persons in charge of selecting type of training, curriculum design, course implementation and evaluation a firm ground for decision making. Now we have reached Level 6 in Figure 1, where the training place and the curriculum design have to be decided. The two are often very closely linked, each institute of education has its worldview and view on how HCB is best approached. In the next chapter we will look into advantages and disadvantages of overseas training.

Selecting training place - overseas contra local

When we talk about HCB within ‘Tropical Animal Husbandry’ it often implies shorter or longer overseas stays. Either in the form of persons from the third World go for training in the industrialised world or people from the industrialised world goes for training in the third world. It lays in the mind of most educated people that overseas training is always better than local training, especially when it implies trainee's from “South” going to the “North”. We will argue that it is no “law of nature” that overseas training will be the best way of HCB neither to the employing organisation nor to the individual trainee. One should in each HCB case assess carefully what the potential advantages and disadvantages are of different training options.

Talking about overseas training one should not neglect the fact that this is a million dollars business with often overwhelming financial motives. Not only dos it often prove to be a quite lucrative business for the trainee, the hosting institution itself make substantial financial gains on training overseas students and might depend on this revenue. Adding to the bias towards overseas training is the fact that in many places it is still considered prestigious to go to the industrialised world for training. However, exchange of teachers and trainers instead of trainees might be a viable alternative.

The individual's perspective (Employee)

How a person will look on an overseas training opportunity will of course be highly individual. Factors like family status, age, gender, income level, previous experience etc. will have various degrees of impact. Table 1 is, nevertheless, an attempt to list different advantages and disadvantages, which an individual might encounter when participating in overseas training. The list does not claim to be comprehensive and the reader is welcome to add to it.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of doing overseas training seen from the individual perspective

| POTENTIAL | |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| • Higher education | • Away from family and friends |

| • Financial benefit | • Loneliness |

| • Prestige | • Low status in visiting country |

| • Enhanced job possibilities | • Difficult living conditions |

| • More security | • Unfamiliar approaches to the concept of learning |

| • Broader world view | • No guarantee for relevant training |

| • Improved skills | • Risk of de-motivation when returning to a resources poor environment |

| • Increased motivation | |

| • International network | |

| • Understanding of the “Other way” of doing things | |

As it can bee seen from Table 1 that there is a whole range of good reasons for venturing into HCB in the form of overseas training. The potential disadvantages falls more or less within two groups, one is related to social status and life in a foreign country, and the other one to the type and quality of training the individual is offered. Both types of disadvantages can be reduced by proper arrangements.

It could be argued that a partly overseen benefit from overseas training is that the overseas students are exposed to a different approach to learning. This is particularly true for many African students and to some extent for Asian and Latin American students. The education system in many former colonies are remedies of the old colonial system, which means that their approach to learning has remained unchanged for half a century. This system was designed to serve the colonial administration, not to enable the developing nations to gain a maximum from their educational sector and other HCB efforts. Approaches in HCB and the general development of a society are somehow interrelated. Society will demand people with new and different skills and the worldview the population has gained through education will have an impact on how society develops. It is our experience, that the exposure to a modern educational system which is in line with it's surrounding society, can give the trainees a benefit from overseas training that far exceeds the factual knowledge and skills they have achieved. When this is used consciously it can be a strong and relevant argument for continuing overseas training.

The home institution's perspective (Employer)

The aim of the home institution is to provide the best possible training for their employees at the lowest cost possible, see Table 2. The problem here is that aid related HCB is not a free market commodity. Most donors have some degree of restrictions towards how their training funds can be spend. Often they are tied for use in the funding country or even at specific governmental training institutions. Such conditionalities severely limit the employers' manoeuvre room. They can not decide to send a higher number of employees to e.g. India where the cost of training is much lower, regardless if the curriculum there is more relevant or not. In this regard the employee often side with the donor since it is much more prestigious to go a Western country.

A lot of the potential disadvantages listed in Table 2 can be limited by proper planning and management by the employer, both before releasing staff for training, during absence and after returning. The problem of getting staff which is de-motivated or not interested in domestic problems because they have become arrogant to their own ‘low tech’ working environment, can be a devastating disadvantage. The training institutions should be able to design the curriculum so it is ‘state of the art’ and at the same time adapted to the working environment in which it has to be operational. It does not serve the purpose to train people in technologies which are not available at their place of work.

Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of doing overseas training seen from the employer's perspective

| POTENTIAL | |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| • Improved human capacity | • Temporary or permanent brain drain |

| • New technologies and ideas | • Temporary or permanent capacity problems |

| • Closer links to other countries and institutions | • International oriented staff with little interest in ‘low status’ domestic problems |

| • Financial benefit | • More emancipated and demanding staff/citizens |

| • More emancipated and demanding staff/citizens | |

The emancipation it gives the human mind to see other ways of doing things, different organisational structures and different ways of managing a society can be difficult to deal with for the employing institution. Used in the right way it can be a driving force for new inspiration but it might also turn out to block the employee from functioning back in the “old system”.

The host institution's perspective

From the host institutions point of view there is not many disadvantages. Especially overseas trainees paid by the national donor agency can be a very lucrative business, and some training institutions have specialised in this field. If there was free market competition on this field one could hope that it would lead to a situation there customers got more value for the money. However, there is no “law” that say that would happen, it could also lead to the opposite situation. A lot of discount training might be marketed where the curriculum is broad and rather general to cut cost and fit large groups of customers.

The host country's perspective (Donor)

The host country has a more diverse aim with venturing into HCB as part of their aid package, than the host institution for training. Table 3 lists some of the potential advantages and disadvantages of overseas training seen from the donor perspective. The binding of parts of the aid to purchase of commodities and services from the donor country do serve purposes other than the financial. The “ambassador” links it gives in recipient country ministries and other institutions should not be under estimated. Moreover, frequent visits by overseas trainees to home institutions have a high advertisement effect as a physical proof that the aid money is used to something and somebody. And it should not be forgotten that the host institutions also gain new insights, new knowledge and new inspiration from working with trainees with a different background and a different perspective on things.

However, it is an extremely resource demanding approach to send individuals from the third world to the Western world for HCB. More freedom of choice in selecting training institutions and venue could be a welcome incentive for commodity development among institutions providing HCB services within Tropical Animal Husbandry. In order to limit the negative aspects of overseas training and reduce cost many donors opt for the so-called “Sandwich-model”, where the South trainees take theoretical courses in the North, do research at home and come back to the North for write-up.

Table 3. Advantages and disadvantages of doing overseas training seen from the host institutions perspective.

| POTENTIAL | |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| • Financial benefit | • Westernised civil servants who take little interest in poverty alleviation |

| • “Ambassadors” who understand our way of doing things | • Very resource demanding |

| • Closer links to other countries and institutions | • Nepotism and corruption during nomination of candidates |

| • New insights and techniques | |

| • Physical proof of what financial aid is used for | |

| • Broader world view | |

Conclusions

What have been presented are ideas and thoughts in relation to HCB in general. It is difficult to draw general conclusions on the subject. On the other hand when HCB is in question it seems appropriate to start with a description of the HCB needs of the institution and to make a more formal and open selection of candidates for training.

Both training at home and training overseas has advantages and disadvantages which has to be considered and the choice may be one or the other. The so-called “Sandwich model” seems to be the best choice in many situations as it combines many advantages from both home and overseas training. Exchange of teachers between North and South also seems to be able to inspire the trainees/students.

We have brought our own thoughts based on our own experiences and hope that the article has inspired the reader to elaborate on the issue.

References (inspiration - not cited)

Bawden, R.J. (1992). Systems Approaches to Agriculture Development: The Hawkesbury Experience, pp 153–176, Faculty of Agriculture and Rural Development, University of Western Sydney Hawkesbury, Australia.

Bawden, R.J. (1997). The community challenge: The learning response. (Handout)

Brier, S. (1997). “The self-organization of Knowledge: Paradigms of Knowledge and their Role in the Decision of what Counts as Legitimate Medical Practise”, in S.G. Olesen, B. Eikard,, P. Gad & Erling Høg (eds.), Studies in alternative Therapy: Lifestyle and Medical Paradigms, Odense University Press, pp. 112–135.

Brown, J.S., Collins, A. and Duguid, S. “Situated cognition and the culture of learning”, Educational researcher, 18:1 32–42.

Chambers, R. (1983). Rural Development: Putting the Last First, Longman, New York.

Chambers, R. (1993). Challenging the Professions: Frontiers for the rural development, London: Intermediate Technology Publications Ltd.

Chambers, R. (1998). Research methods in development work, Workshop at Holmen, 25th February 1998, organised by the School of Architecture, Copenhagen. (Not published).

Escobar, A. (1997). “The making and unmaking of the third world through development” The Post-Development Reader, London & New Jersey: Zed Books.

Klausen, A.L. (1999). What's needed to collaborate with donors? A critical review of qualifications, tools and skills needed, speech by Anne-Lise Klausen, Managing Director, Nordic Consulting Group a/s, FORYNG meeting, 7 June 1999, KVL. (Not published).

Mikkelsen, B. (1995). Methods for Development Work and Research: A Guide for Practitioners, New Delhi/Thousand Oaks/London: Sage Publications.

Mogensen, J. & Dahl, A. (1990). The Hawkesbury-Model: An experience based system oriented education within Agriculture, M.Sc. Thesis, Department of Agricultural Sciences, KVL (The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Copenhagen). (Danish version).

Monu, E.D. (1997). “Farmer Participation in Research: Implications for Agricultural Development”, Journal of Social Development in Africa, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 52–66.

Pretty, J.N. (1995). “Participatory Learning for Sustainable Agriculture” (International Institute for Environment and Development, London, U.K.), World Development, Vol. 23, No. 8, pp. 1247–1263.

Pretty, J.N. (1996). “Participatory Learning for Integrated Farming”, in Frands Dolberg and P.H. Petersen (eds.), Integrated Farming in Human Development, Proceedings of a workshop at Tune, DSR Forlag, KVL (The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Copenhagen), Denmark, pp. 13–34.

Rigg J. (1999). The Role of Research in Aid and Development, handout from ‘Development and Aid - the interaction between development and aid in the process of development’, Danish Association of Development Researchers (FAU), Annual Meeting 4–6 March 1999, Gjerrild, Denmark.