As previously mentioned, fry of different ages and sizes (8 days, 3 cm, 13 cm, etc.), are produced either in the State-run fry-rearing stations (e.g., district and State farm), or in the centres run by the people's communes (Section 5). These stations generally produce fry not only for their own requirements but to sell to other groups of fish cultivators. This activity can in fact constitute a fairly large proportion of annual income from fish culture.

The technology used for the transport of fry and fingerlings depends mainly on the rate of dissolved oxygen consumption (RDOC) of the fish transported. A few typical examples are given in Table 37. A review of these figures suggests that:

Table 37

Dissolved oxygen consumption rate of Chinese carp fry

(adapted from Anon., 1980, page 68)

| Species | Water temperature (°C) | Unit weight (g) | Dissolved oxygen consumption (mg/g/h) |

| Bighead carp | 27.8 | 0.00251 | 5.130 |

| 28.9 | 0.815 | 0.893 | |

| 30.0 | 1.02 | 0.912 | |

| Silver carp | 26.0 | 0.00245 | 5.000 |

| 18.0 | 9.00 | 0.280 | |

| 21.5 | 9.66 | 0.318 | |

| 24.2 | 13.50 | 0.224 | |

| 29.0 | 15.00 | 0.293 | |

| Grass carp | 27.5 | 0.0027 | 4.140 |

| 32.0 | 0.0027 | 4.350 | |

| 30.0 | 0.36 | 1.000 | |

| 22.0 | 9.33 | 0.296 | |

| Mud carp | 26.0 | 8.50 | 0.230 |

| 26.0 | 10.00 | 0.190 |

This shows that three major rules regarding fry transport must be followed. The weight of fry and fingerlings/litre of water:

Attention must also be paid to the duration of transport.

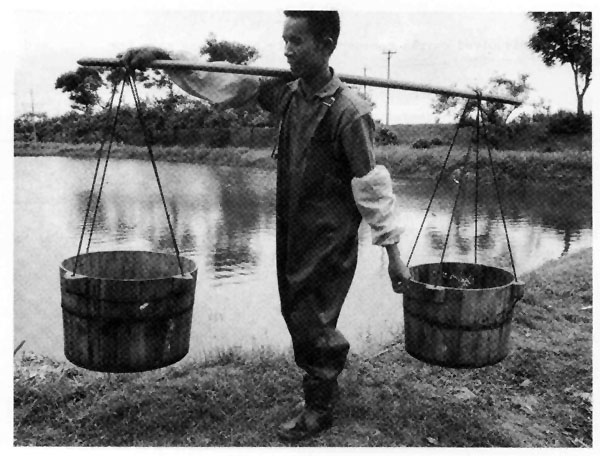

Several methods of transport are currently used in China. For short distances, woven bamboo baskets or wooden buckets are preferred. They are suspended to each end of a bamboo pole, which is carried on the shoulder (Figure 67). For longer distances, various containers made of waterproof canvas or wood, boats with perforated sides, as well as plastic bags are used.

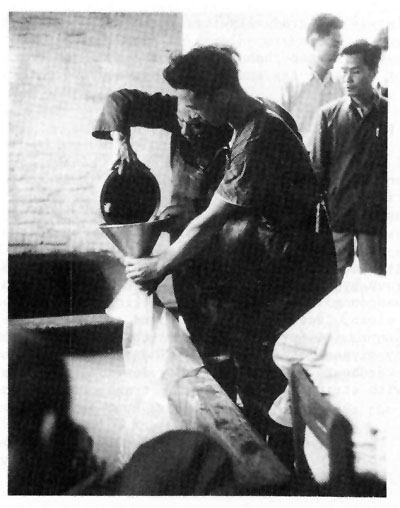

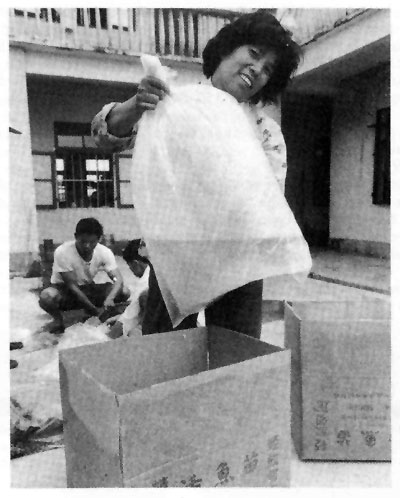

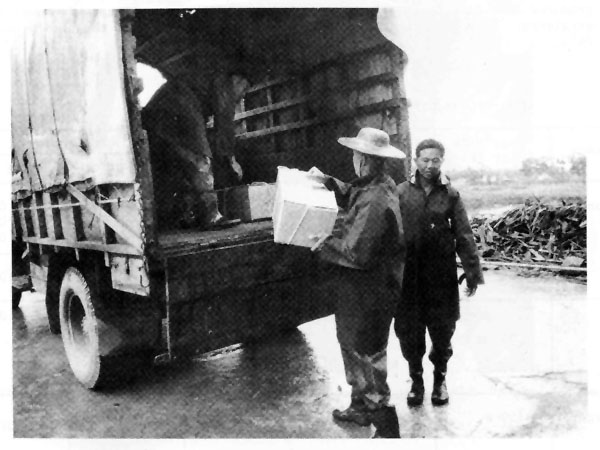

The use of the latter method is becoming increasingly widespread and it was demonstrated to the study group by the technicians at the Hengjiang Fry-Rearing Centre (district of Xinhui, Guangdong). It consists in filling a plastic bag (polyethylene, 0.5–0.1 mm thick) with clean, fresh water, to a third or a quarter of its capacity (Figure 68). A known quantity of fry are placed in it. The air in the bag is then expelled and replaced by oxygen under pressure. The bag, which is hermetically sealed, is then laid flat in a cardboard carton, specially designed for this purpose (Figure 69). The carton is tied up with string and is ready for transport by road, rail, or even air (Figure 70).

Figure 67 Transport of fry over short distances (Photo: F. Botts)

Figure 68 Preparation of plastic bags for transporting eight-day old fry, Xinhui Fry-Rearing Centre, Guangdong

Figure 69 Plastic bags containing the fry are inflated with air and placed in cardboard cartons

Figure 70 Fry transport in baskets (Photo: F. Botts)

The stocking rate (g/litre) of the fry in the plastic bag depends on the species, temperature, transport time, the individual size of the fry, their physical condition and their degree of ‘training’. Stocking rate tables were prepared on the basis of experience. At the fry-rearing centre visited 20-24 h transport is organized for eight-day old fry. Each plastic bag contains eight litres of water. The stocking rate for this bag would be 80 000–100 000 grass or silver carp fry or 150 000 mud carp fry.

The following are a few practical points which must be borne in mind in order to increase the fry's chances of survival:

The selling price is fixed by the Government of each province. It also varies according to the species and size of the fry (Table 38). As an indication, the cost prices given by the Chinese technicians are also mentioned, although it is difficult to give an exact definition for each case of the real basis on which these prices were calculated. It appears that in almost all cases, amortization of fry-rearing installations is not included.

Over short distances, either in the farm itself or in the people's commune, the locally produced food-fish is usually transported live, in large waterproof canvas or wooden containers. They are first weighed dry, in a woven basket, at the pond's edge (Figure 76).

Table 38

Cost price and selling price of fry in 1980

| Province | Age/size of fry | Species Chinese carp | Price (Y) | |

| Cost price | Selling price | |||

| Guangdong | 8 days | mud carp | - | Y 2/10 000 |

| silver and bighead carps | - | Y 4/10 000 | ||

| grass carp | - | Y 5/10 000 | ||

| 3 cm | mud, silver, bighead and grass carps | Y 30+/10 000 | Y 36.8/10 000 | |

| Hubei | 8 days | silver, bighead, grass carps | - | Y 4.99/10 000 |

| 13 cm | silver, bighead, grass carps (in cages) | Y 200/10 000 | - | |

| 17 cm | silver, bighead, grass carps (in ponds) | Y 300-600/ 10 000 | - | |

| Zhejiang | 150 g | silver, grass, bighead carps (in cages) | Y 1.04/kg | Y 1.30/kg |

When the fish is to be sold outside the people's commune, larger transport facilities are used. These usually include the transport of live fish in boats, whose holds are arranged in perforated compartments in which a small current of water circulates. The tonnages of these boats vary between 3 and 30 t (Figure 73).

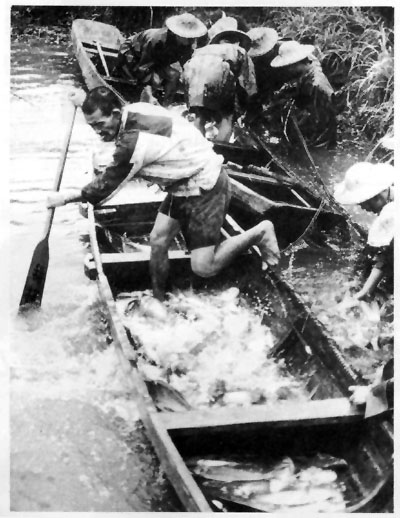

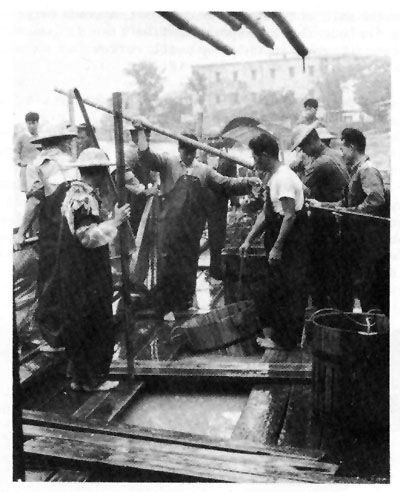

The study group observed the first stages of the marketing circuit of farm-reared fish when it visited the Leliu People's Commune (Guangdong). Fish, stored in a channel, were harvested with seine nets and placed in light boats, partially filled with water (Figure 71). They were thus transported toward one of the three State purchasing centres a few kilometres away and situated on the edge of a navigable channel in the Xi Jiang delta. There, the fish were sorted by species, weighed and transferred to one of the perforated compartments of an 8-t capacity transport boat (Figures 72 and 73). Several of these boats leave the purchasing centre each day and transport their cargo of live fish to the Guangzhou Aquatic Product Company Centre, 62 km away. From there, the fish are either distributed to the different markets of the town or transferred to other larger boats for export, still alive, to Hong Kong.

Figure 71 Transporting harvested fish in a flooded boat. Leliu People's Commune, Guangdong

Figure 72 Delivery, sorting and storing of food-fish at the floating purchasing centre

Figure 73 Loading a transport boat with live fish at the purchasing centre. (Photo: F. Botts)

Almost all the farm fish are marketed fresh and a large number are even marketed alive, especially in South China. Once the fish have reached the end of the rearing cycle, they are harvested and if necessary, stocked in storage ponds or channels to await demand before marketing. Every possible effort has been made to locate production zones close to consumption centres, in order to reduce transportation problems to a minimum. The current trend is therefore to intensify fish production in the areas immediately surrounding large towns, such as Shanghai (Section 7.1).

In most people's communes, production meets local requirements. Distribution of fish to members is organized by the marketing centre which serves each production unit. This centre is in fact concerned with purchasing fixed quotas and transporting them to the markets. They work in close collaboration with the producers so as to ensure a regular supply to the market.

Marketing of fish outside the people's communes is controlled and run by the State through purchasing centres. The latter buy the fish directly from the producers (people's commune, State farm, district, etc.), at a fixed price. They transport it, usually alive, to the prefecture, distribution centres, district or province (Aquatic Products Bureaux), from where the fish is transferred to the different markets.

The selling price of the fish is also fixed by the State. It varies in a single province according to the place and the species (Table 39). It can thus be higher in urban than in rural areas. The grass carp obtains a higher price than the other Chinese carps. The black carp, common carp, Wuchang bream and crucian carps can be sold at a higher price than the silver carp, bighead carp or tilapia.

Table 39

Selling price of farm table fish in 1980

| Province/municipality | Producer selling price, Y/kg | |

| Silver/bighead carps | Grass carp | |

| Guangdong | 1.00 | 1.50 |

| Hubei | 0.62-0.78 | 1.10 |

| Zhejiang | 0.96 | - |

| Jiangsu | 1.00a | 1.30b |

| Beijing | 1.50 | - |

a Same price for tilapia

b Same price for black and common carps, bream and crucian carps

Market size of table fish also varies according to the region. It seems that in the south, it is larger than in the centre and north. In the Guangdong province, silver, bighead and grass carps are eaten when they reach 1–1.5 kg. In Hubei province, on the other hand, a weight of 0.5–1 kg suffices. Mud carps and tilapia are two relatively small species which are marketed when they reach 125–250 g. Consumers however, prefer the larger specimens.

Average fish consumption in China is currently estimated at around 4.5-5 kg/year per caput. Real consumption however varies considerably from region to region. It would appear that some provinces consume very little or no fish at all (e.g., Shanxi). The southern regions of China, however, consume much more than the northern regions. Considerable variations may also exist within a single province. In the Guangdong province, for example, annual average per caput consumption is approximately 5 kg in Guangzhou, while in the Leliu People's Commune (Shunde district) it is 50 kg - ten times more.