The organization of the study tour was excellent on the whole. From their arrival in Beijing until their departure, the participants were taken in charge by their Chinese hosts. The overall programme prepared at the outset was rigorously respected in each province and municipality visited. In three weeks of intensive exchanges, this programme made it possible for the many aquacultural activities in five different regions to be fully appreciated.

It became obvious during the tour however, that some improvements could be envisaged for future similar tours. Participants suggestions refer mainly to the different briefings of a general nature which were given upon arrival in each province and municipality. It soon appeared, that in spite of the commendable efforts of the translators, many difficulties kept arising, for example, the names of people and places. It was also very difficult for the participants to follow the proposed itineraries and to be aware of the geographical location of the places visited or mentioned during discussions.

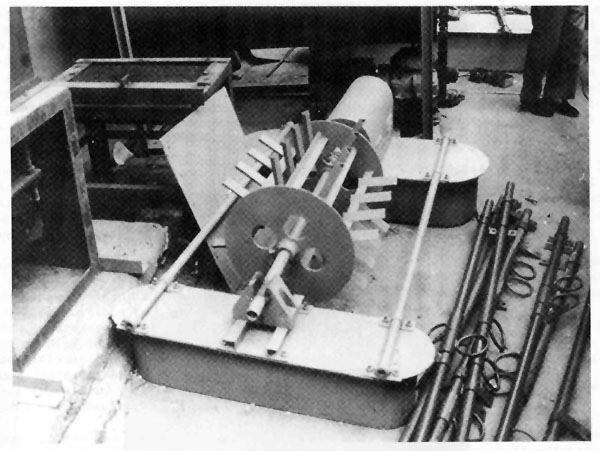

Figure 74 Floating paddle aerator fitted with an electric motor, Fish Culture Equipment Factory, ‘Liberation’ People's Commune, Qingpu district, Shanghai

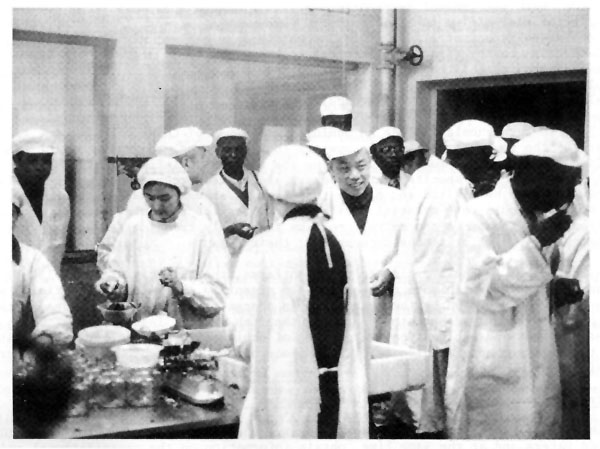

Figure 75 Visit to the fish canning factory, Shanghai Aquatic Products Processing Plant

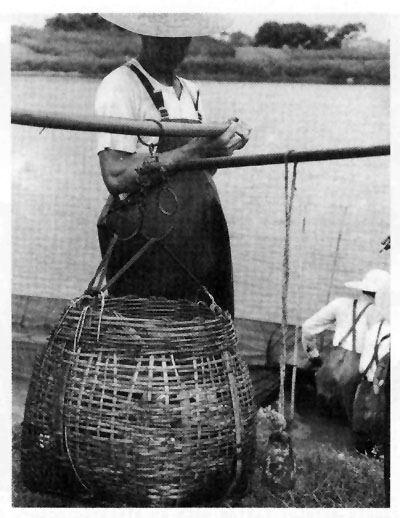

Figure 76 Weighing the harvest at pond's edge

We therefore recommend that for future study tours, greater use be made of audiovisual aids, both for general introductory briefing in Beijing, as well as for later regional briefings. If we take aquaculture, for example, a general briefing could be based on a standard set of slides giving in the form of tables, maps and diagrams, the basic data given in the first four Sections of this report: topography and climatology of China; general administrative organization; aquatic resources; aquatic products; main fish culture species; systems of cultivation; history and analysis of development; central, regional and local organization of aquaculture; research/training. A verbal presentation of this kind should include written diagramatic documentation distributed to each participant. This in turn should include an administrative map of China, showing the general itinerary of the tour, as well as the overall tour programme, the names of the places to be visited and the people to be met. During the regional briefings, this material would be supplemented by more specific data, such as a detailed programme of local visits, the names of places to be visited and people to be met, a schematic map of the regional itinerary. Not only would this material facilitate the task of the interpreters, but would also allow participants to concentrate more on the purely technical aspects of the tour, while being able to refer to the documents at their leisure.

In the course of their visits to the fish farms, the participants immediately realized that these farms were much more successful when organized according to a definite plan. After a brief introduction by the technician in charge, giving a general idea of the main points of the visit, the participants toured the fish culture installations, where on-the-spot descriptions and explanations were given of equipment and techniques used. At the end of the visits a general discussion took place on the main subjects observed during the visit.

The purpose of the study tour was to observe the development of Chinese aquaculture in inland waters and at the same time, obtain information on the organizational and technical aspects of this development. As a result of their observations, the participants would be in a better position to assess the possibilities of transferring the technology to their own countries.

All the participants were favourably impressed by all that the Chinese had accomplished in the field of fish culture. It soon became clear to them however, that it would be difficult to copy what they learnt and hope to obtain the same results. There are too many differences between Africa and China, as regards available resources, national needs, social structures, economic systems, etc. The climate and the water resources can be very different. Even the fish species are essentially different. Not only did the African participants therefore have to take an interest in the technical aspects, but, more importantly, in the guiding principles which made this rapid development of aquaculture possible in the Chinese rural environment.

There is no doubt that one of the major reasons for this success lies in the long tradition of fish culture and relatively intensive farming in the inland waters of China. There is no such tradition in Africa and this is a clear handicap. A similar situation concerns command of the water, which is another major asset in China and which in Africa is found on a comparable scale only in Madagascar.

Integration of fish culture into other production activities, allowing maximum utilization of land and water resources, is the most outstanding aspect of Chinese aquaculture. Integration can be applied directly to rural development programmes in Africa, even though it may not be possible to transplant the system observed during the study tour in its present form. Fish species, as well as the types of cultivation and rearing methods must be chosen according to local conditions. In recent years, efforts have been made in several of the participants' countries (e.g., Central African Republic, Congo, Ivory Coast, Madagascar) to introduce and develop this type of integration. Many opportunities also exist in other countries (Cameroon (United Republic of), Gabon, Guinea, Upper Volta, Rwanda, Senegal, Zaire) and they should be exploited as far as possible.

Organization and planning of aquaculture development in China are of course adapted to the social and political system of the country. Major difficulties of adaptation would be encountered in most of the participants' countries. Nevertheless, it appeared that two major principles could be applied:

Scientific research in aquaculture is conducted not only in the specialized laboratories of the institutes and universities, but also at all intermediate levels up to production brigade level, in the very heart of the rural environment. Close ties exist between the different research units at people's commune, district, provincial and national levels, which ensures the coordination, control and support necessary at all levels. This close relationship between researchers and producers makes it possible for the results of scientific research to be put into practical application and not remain theoretical, as usually happens in many other countries.

Training and education in aquaculture are also directed toward integration of the practical with the theory: theoretical teaching and practical experience are closely related. Technicians and rural fish culturists are trained locally in the communes and production brigades, by teachers from technical schools and even universities. This allows the latter to find solutions to existing production problems on the spot. Rural producers can however, also obtain theoretical training in specialized centres, while at the same time working on practical aspects and on solutions to fish culture problems.

The application of the ‘three in one’ principle to planning, research and aquacultural training results in very efficient rural extension. Among the results that the members of the study tour were able to appreciate were those obtained at fish production level.

Simultaneous development of all local resources is widespread in China and application of this principle is valid for most of the participating countries. For example, aquatic plants, considered a nuisance and removed in many countries, are systematically cultivated in China and used for animal feeding and for making compost. Use of silt from ponds, lakes and rivers for organic fertilization and improvement of soils, as well as the use of molluscs for animal feeds, are two further examples.

During the study tour, the participants were able to get to know the different farming systems used either in ponds, lakes, rivers or channels. In ponds, the farming system is usually semi-intensive, based on polyculture, organic fertilization and plant feed. In open waters, on the other hand, it tends to be extensive, based on natural food and periodic stocking of young fish. Although the species native to Africa are not the same, many of the principles of management applied in China could be successfully adopted there.

Two major recent developments in Chinese aquaculture are controlled spawning of Chinese carps and large-scale production of Chinese carp fry. The first problem does not yet exist in Africa, where raising of the different species of tilapia is possible with natural spawning methods. There are some exceptions however, where, for example, attempts are being made to develop cultivation of catfish (e.g., Cameroon (United Republic of), Central African Republic) or common carps (e.g., Cameroon (United Republic of), Central African Republic, Ivory Coast, Madagascar) or Chinese carps (e.g., Ivory Coast, Madagascar). In these particular cases, more use could and should be made of the Chinese experience with controlled spawning. On the other hand, large-scale production of fry in the rural areas of Africa has not yet been done, even for tilapias. While in China, large quantities of fry are very often produced locally by the peasants themselves, in Africa, this technique, when it exists, is still the domain of the technicians and the State-run fish culture centres. There again, decentralization of fry rearing, as done in China, could be adapted and encouraged and this would make up for the present shortage of stocking material and ease the difficulties of distribution over vast areas in the absence of an adequate communications system.

Once sure sources of fry become available, it will be possible to adapt the Chinese system of semi-intensive fish farming fairly easily to some African regions, first of all where integrated rural development exists and where producer associations are established, e.g., in a cooperative form as in Cameroon (United Republic of), Congo, Ivory Coast, Rwanda and Zaire. In the absence of a well-defined technology allowing polyculture production of a large number of African species, mixed farming of Sarotherodon niloticus (plankton feeder) and Tilapia rendalli (macro-phytophagic) can give excellent results provided that organic fertilization and feed based on plants and agricultural by-products are applied in accordance with the Chinese semi-intensive system of cultivation.

There seems to be a need however, to develop more complete systems of polyculture in research stations and in Africa, using native species (i.e., different tilapias, catfish) and if necessary, exotic species (e.g., Chinese and Indian carps).

The study group was able to observe on several occasions how skilful application of fish culture techniques to fishery development could be profitable in natural lakes and reservoirs. Extensive polyculture allows complete use to be made of natural food and sometimes even residues from nearby lands. Annual stocking maintains high levels of production. Integrated development of watersheds (e.g., forests, agriculture, livestock farming, fisheries, tourism) guarantees protection of the latter, while optimum use is made of resources. All these aspects and their possible application to developing countries, have been thoroughly dealt with in a previous report (Tapiador, et al., 1977). For Africa, in particular, application of the extensive fish culture techniques used in China could be envisaged, especially in the many small and medium irrigation reservoirs of the Savanna regions in Cameroon (United Republic of), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo.

Farming by means of extensive fish culture in pends in sections of rivers and channels also attracted the interest of the participants. Here again, the combination of periodic stocking and polyculture produces attractive output results. However, transfer of this system to other countries, where the notion of collective property ownership and community administration does not exist, could raise various problems, e.g., regarding legislation, environment and management. In most African countries, this type of fish farming is likely to be hard to apply. It could however, be possible in certain cases, such as downstream from hydro-electric dams and in certain seasons, as well as in the main irrigation canals of agro-industrial complexes, when there is no chemical pollution.

On the other hand, special attention must be paid to the use of fish culture pens in African lakes and reservoirs. Although the participants had the opportunity of observing only one of this type of installation - fry production in a bay in a reservoir - they expressed unanimous interest in the export of this technology to their countries. Unfortunately, no experiment of this type has yet been tried there on a large scale. Research on this subject, with a view to producing not only stocking fingerlings, but also table fish, using a semi-intensive system of cultivation, should be undertaken in Africa.

Cage farming whether carried out in reservoirs, rivers or navigable channels, aroused the most interest. All the systems of cultivation - extensive or semi-intensive, in floating or fixed cages, at experimental, pilot or commercial level - have unquestionable potential for the African countries. Before they could be disseminated however, the problem of regular supplies of fry of the species chosen would have to be solved - in this case an African tilapia and preferably S. niloticus. If abundant natural food is not available in the cages, good quality artificial feed will have to be provided, using for example, agricultural by-products available locally. Africa already has some experience in these fields (e.g., Benin, Ivory Coast) and there are many opportunities for their development in most of the participating countries. Rapid progress could be made, as in China, provided that the necessary inputs were available.

To conclude, several of the principles to which success of the large-scale development of Chinese aquaculture over the last 30 years is due, could be applied in Africa. These principles refer mainly to administrative organization on both the national and regional scales, to the planning process, to the organization of research and training, to rural development planning, as well as to the choice of a fish culture technology suited to local possibilities.

The Chinese experience, empirically acquired over several centuries of practice with fishery/fish culture and agriculture/fish culture integration, is considerably valuable to African countries which are interested in integrated rural development. It cannot however, be imported without being adapted to local conditions. In fact, in most of these countries more emphasis will have to be laid on economic, social and nutritional benefits. In order to dispose of the skilled labour needed to make the units economically profitable, it is more than likely that producers' associations will be necessary.

There is great potential in Africa for current Chinese technology adapted to tilapia farming in ponds, pens and cages. Small and medium-size irrigation reservoirs in savanna regions could also be set up along the lines of Chinese installations in this field. These fish culture development potentialities would come to nothing unless large-scale production of fry were carried out and suitable farming systems put into practice. As regards the latter, priority could be given to semi-intensive pond polyculture, semiintensive cultivation in lake enclosures and to extensive and intensive farming in cages. Research on fine points and pilot assessment projects should in turn provide the bases for fish culture development, within the overall framework of integrated rural development.

China has a very long experience in fish and intensified fish culture in combination with crop and livestock farming. The greater part of its success in aquaculture is based, not on scientific results, but on the contrary, on empirism. As they emerge from complete isolation which lasted about 10 years, researchers and technicians feel a great need to find out about the progress made in the rest of the world during that time. The participants were aware of this throughout their long trip across the country.

Unfortunately, since aquaculture development in Africa is still in its initial stages, little basic technical information could be exchanged with our Chinese hosts on this subject.

Their attention was drawn to some of the progress recently made in Africa: production on a pilot scale of male S. niloticus in commercial ponds (Ivory Coast); the establishment of modern, Hungarian-type hatcheries for common and Chinese carps (Madagascar), and intensive farming of tilapia in floating cages (Ivory Coast).

Other African ventures should materialize in the near future and could then become additional sources of valuable information for Chinese technicians. These could include fish cultivation in lagoon enclosures (Benin, Ivory Coast); intensive, commercial farming of tilapia in cages, lagoons (Ivory Coast) and reservoirs (Ivory Coast, Upper Volta); large-scale production in modern hatcheries of catfish fry, Clarias lazera (Central African Republic); management of modern hatcheries for large-scale production of common, grass and silver carp fry (Madagascar), and polycultural farming in coastal pilot farms of mullet, Chanos chanos and Peneidae shrimp (Madagascar).

There is therefore little to be learnt by China from current achievements in French-speaking Africa. If aquaculture development follows its present course however, an increasing amount of information of interest will appear in the next five years.

On the basis of the conclusions expressed above, we can offer a series of recommendations. They may be subdivided into two groups, depending on whether they refer to aquaculture development in French-speaking Africa (Sections 15.4.1 and 15.4.2) or China (Sections 15.4.3 to 15.4.8).

Even though the experience accumulated in China has been empirical, it is extremely valuable for African countries wishing to undertake integrated rural development. For purposes of dissemination, it is recommended:

In fact, these two recommendations could be combined. In addition, it is suggested that they be carried out in close collaboration with the new Main Regional Centre of Wuxi (Jiangsu), which was set up with UNDP/FAO-ADCP assistance and whose primary purpose is to organize training and research on integrated fish culture.

One or several species of Chinese carp have already been imported by some African countries (e.g., Ivory Coast and Madagascar), while other countries are planning to do so. There is little doubt that technical assistance will be necessary to establish simple, but productive hatcheries, with a view to producing large quantities of eggs and fry. A similar problem faces certain countries which have imported other exotic species (e.g., common carp) or which are trying to produce local species which do not easily spawn in ponds (e.g., catfish).

In these particular cases, it is recommended that competent Chinese technicians be called upon to launch systems suited to local conditions.

Research must be carried out in China to establish scientific bases for techniques which are used empirically in integrated fish culture/agriculture/livestock farming development. A critical and rational analysis of results observed is required if the high outputs obtained locally and sporadically are to be the general rule. This analysis is also absolutely necessary if the real nature of the mechanisms involved are to be understood. It would then be possible to adapt them to new situations and to apply them with as much success.

The Main Regional Aquaculture Centre at Wuxi (Jiangsu), one of the four regional centres forming the Asian network (Project UNDP/FAO-RAS/-16/003), which was opened this year, was designed for this purpose. Chinese technicians receive specialized training in this field, basic and applied scientific research is carried out and an information centre specializing in integrated aquaculture will be set up.

The technology used for controlled spawning of brood fish, incubation and hatching of eggs in Chinese hatcheries is relatively simple, even though it enables massive quantities of fry to be produced. Although the installations are not costly and are easy to maintain, they do not allow effective control to be exercised over the different production phases, such as fertilization, incubation, hatching and the removal of dead/diseased eggs. This could explain the relatively low rates of fertilization and hatching which have been noted in some hatcheries.

It would be useful to compare the results obtained using this technology with those obtained using modern technology which allows a tighter control to be kept on all phases. This could include artificial fertilization, the use of methods to encourage fertilization, the use of incubating jars, as well as the use of chemical treatment during and at the end of incubation, according to the methodology successfully applied on a large scale in Hungary.

To enable Chinese technicians to familiarize themselves with this new methodology, it is recommended that two to three month-long practical training courses be held for them at the Szazhalombatta hot water hatchery in Hungary. These courses could be followed by a one to two week stay at the hatchery of the Organization for the Improvement of Inland Waters (OVB) in Lelystad, Holland, during the common and grass carp production season.

On the basis of observations made during visits to some installations and the technical data obtained, it would appear that currently used technology could be substantially improved. Yields are in fact rather low, especially when relatively rich artificial feeds are used. This may be due to several reasons: e.g., use of nets whose meshing size is too small (loss of water exchange) and too low stocking densities and rates.

It is recommended that study tours and short practical training courses be organized for Chinese technicians in institutions and commercial installations with a solid experience in fish production in cages. As far as cage cultivation in China is concerned, the following countries are experienced on the subject: USA (trout, tilapia, catfish); Hungary (Chinese carps, pike-perch, sturgeon); Holland (common carp, grass carp, rainbow trout); Philippines (tilapia), and the German Democratic Republic (common carp, rainbow trout).

There is an increasingly urgent need to set up intensive fish culture farms in suburban zones in eastern China. Trials are underway, but most of them have not yet reached pilot stage. To accelerate development of these farming systems, and so that they may benefit from the experience gained by other countries, it is recommended that study tours and practical training courses be organized for small groups of Chinese technicians. During these visits, they could be shown intensive farming in raceways and round ponds, technology using water recirculation, manufacture and distribution of artificial feeds, as well as modern methods for manipulating cultivated animals. Aspects regarding economic profitability of intensive farming should also be closely examined. Visits could be organized to the USA, Great Britain, Italy and Japan, to both Government and private installations.

As previously mentioned, China's complete break with scientific research and technological development in foreign countries over the last 10 years constitutes a serious handicap today, in spite of recent efforts in opening their doors to the outside. Their research institutes, centres of higher education and their technicians are desperately in need of foreign publications and reference material relating to recent developments in aquaculture and related sciences.

It is recommended that in every province, municipality and autonomous region where aquaculture plays an important role, a specialized documentation centre be set up and equipped. Basic modern documentation should be provided, in the form of microfiches, for example. Equipment for reproducing the latter would allow them to be distributed on a large scale and cheaply to specialized institutions in the region, which would also be equipped with microfiche readers. It is furthermore recommended that these centres be established in close collaboration with the UNDP/FAO Documentation Centre in Wuxi (Main Aquaculture Regional Centre - Asia network). Training courses could also be held for the people who will run the new documentation centres.

The foundations for close collaboration with FAO have been laid, in particular with the Fisheries Department, through its Inland Water and Aquaculture Resources Service (FIRI) and its Aquaculture Development and Coordination Programme (ADCP). This collaboration should not only be pursued, but it should be strengthened in the coming years, mainly through common interest for establishing and developing the Main Aquaculture Regional Centre in Wuxi.

It is recommended that within the framework of this collaboration, more encouragement be given to exchanges of information between FAO technicians and technicians from the National Bureau of Aquatic Products. The exchanges should be in the form of working sessions and the provision of specialized publications.