"The main benefits are not increases in fish catches, but better communication among users and between users and government, sharing of experience and competence, and a greater sense of being heard."

Niklas S. MATTSON

Wolf D. HARTMANN

Thomas

AUGUSTINUS

MRC Fisheries Programme

Vientiane, Lao PDR

This paper summarizes some of the main experiences gained from the Mekong River Commission Fisheries Programme Component: Management of Reservoir Fisheries in the Mekong Basin (MRF) concerning relations between fisheries information and management. The Component initially worked mainly within the central government line agencies but has gradually become more involved at local user level. The first phase of the Component (MRF I) was initiated in 1995. The second phase (MRF II) started in March 2000 and will be completed in early 2004. In this phase, a fourth riparian country (Cambodia) joined the activities of the Component.

During the first phase, the Component focused on strengthening government staff capacity in Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam. Most activities were carried out at relatively large reservoirs in Lao PDR and Thailand or smaller reservoirs in Viet Nam and included training and implementation of catch assessment and socio-economic surveys. These activities included data storage, analysis and reporting. Reservoir fishery management issues were generally addressed indirectly because of the focus on building the capacity of government staff within a few specific areas. The outputs during the first phase generally related more to policy issues and statistics (data collection) than to management, which became the main focus during the second phase of the Component.

Example of an MRF Phase I output: Study on the fishery of Nam Ngum Reservoir

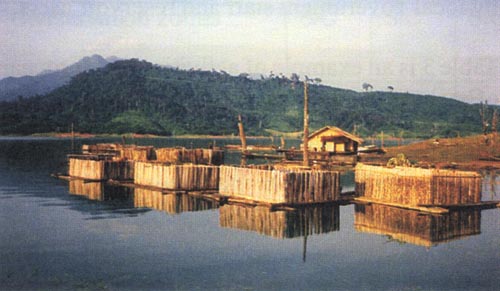

The Nam Ngum is a 477 km2 hydropower reservoir located 90 km North of Vientiane, the capital of Lao PDR. A study carried out by MRF I in 1998 estimated that the fisheries landings from Nam Ngum had increased by a factor 4 over the 16 years between 1982 and 1998 (Mattson et al., 2001). The estimated landings in 1998 were 6,833 tonnes (95% c.i. 4 283 to 9 383), which corresponds to a yield of 143 kg/ha/year.

The increase in the catch can be explained by the increase in effort, particularly gillnets (Table 1). Figure 1 shows a comparison between the official statistics on landings at Nam Ngum in 1997 and the estimate of 1998 total landings by MRF I. The official figure was obtained from trade data supplied by the monopolist fish trader (fish exported from the reservoir), and adding an estimate of local fish consumption (Schouten, 1998). The 1998 fisheries total landings were estimated by catch-effort sampling and a fishing effort survey. The amount consumed locally was estimated from a survey carried out among villagers living around the reservoir.

Table 1. Nam Ngum 1982 and 1998

|

|

1982 |

1998 |

|

Population |

9 560 |

16 660 |

|

Full-time fishers |

1 350 |

1 500 |

|

Total fishers |

2 350 |

3 400 |

|

Gillnet effort |

940 000 |

4 300 000 |

|

Beatnet effort |

None |

195 000 |

|

Net types |

Multi-filament |

Mono-filament |

|

Motorized boats |

563 |

1 286 |

Figure 1: Official versus MRF I estimate of fish production

Nam Ngum Reservoir (Metric tonnes)

It may be concluded that calculation of fisheries landings from Nam Ngum using trade data led to an underestimate of the landings. Figures from other inland fisheries in the region show that this magnitude of underestimation is not unique to Lao PDR (Coates, 2002).

MRF Phase II

In Phase II, the Component focus was shifted toward participatory resource management. The target group (co-managers) include line agency counterparts, local government staff (e.g. district level) and resource users (fishers). To a large extent, the Component is concerned with facilitating communication between co-managers. A central output is jointly formulated reservoir fisheries management plans. An adaptive planning and implementation process is emphasized with joint monitoring of outcomes.

The Component definition of the term management is quite wide: "Any planned interaction that is needed or aims to maintain the productivity of the resource".[4] Co-management is characterized by the sharing of decision-making in management and includes applied management instruments between government and users. Communication is seen as a cornerstone of the co-management process.

Before managing, indeed before planning for management, it is necessary to decide on the main concerns and objectives. Only then is it possible to choose management measures and interventions and the means to implement them. Once there is agreement on management concerns, objectives and measures to be taken, the question to be answered is: "What shall the institutional and organizational framework for management planning and implementation be?" Table 2 summarises some outcomes of participatory workshops at reservoir level in the four riparian countries.

Table 2: Management concerns, objectives and measures

|

Country |

Management Concerns |

Management Objectives |

Actions/Instruments |

|

Cambodia |

Effort increase |

Income diversification |

Training |

|

Lao PDR |

Low/decreased yields |

Income diversification |

Training |

|

Thailand |

Low/decreased yields |

Income diversification |

Training |

|

Viet Nam |

Low/decreased yields |

Income diversification |

Training |

Based on the initial identification of concerns, objectives and measures, specific management plans for each reservoir were jointly formulated by local government staff and reservoir users.

Table 3 is an example of activities that form part of management plans at four reservoirs in Lao PDR.

Table 3: Reservoir Fisheries Management Plans, Lao PDR

|

Activities |

Reservoirs |

Results |

|||

|

NH |

NS |

HS |

PP |

||

|

Organize reservoir fishing committee (RFMC) |

S/C |

S/C |

S/C |

S/C |

4 RFMC's organized and functioning |

|

Data collection |

S/C |

S/C |

S/C |

S/C |

Baseline figures collected |

|

Review fishing regulations |

S/C |

S/C |

S/C |

S/C |

Improved regulations drafted |

|

Conservation zones |

S/C |

S/C |

S/C |

S/C |

A set of proposals for each reservoir formulated, areas demarcated and regulation enforced |

|

Stocking |

P |

P |

P |

P |

JUGO Workshop prepared. |

|

Cage-culture |

P |

|

P |

P |

JUGO Workshop conducted, cage-culture proposals for each reservoir formulated |

|

Organize fisher groups |

S/C |

S/C |

- |

- |

Informal groups organized |

NH = Nam Houm NS = Nam Song HS = Huay Siet PP = Pak Peung

P= Planned Activity S/C = activity has started or is completed

JUGO = Joint user-local government officer workshop

Information for co-management

As Component activities moved from the first to the second phase, requirements for fisheries information did not diminish. However, the nature of the information needed and the methods for collecting the information changed dramatically.

The information required for supporting co-management systems depend on a number of factors including:

The nature of the co-management arrangement (who is involved?)

The objectives of the specific reservoir management activities

The institutional capacity (what are the decision-making methods, how is data collected and analyzed)

The co-managers' preferences and (local) conditions under which they operate

Thus the information requirements must be determined by what is needed to address the management objectives. It is crucial to consider the usefulness of the information before it is collected. Managers must feel a sense of ownership about the information and every effort made to ensure that it contributes to a perceived increase in shared knowledge.

Does co-management work?

Results of a first one-year cycle of planning and implementation in Viet Nam and Thailand have shown promising results. Benefits monitoring has been based mainly on a few broadly formulated indicators that are meant to capture the co-manager's own perceptions. While some are more and others are less satisfied with the planning as such, most claim that they have gained some benefits from the joint management system. The main benefits mentioned so far are not increases in fish catches but better communication among users and between users and government, sharing of experience and competence, and a greater sense of being heard. There is also a high level of satisfaction with specific management activities such as the establishment of conservation zones and formulation of fishing regulations.

Problems and constraints

The process of helping people organize and implement co-management is a time consuming task. Numerous meetings and facilitated events are usually required to build up the confidence and capacity of prospective co-managers. Although co-management is often described as a cost-efficient approach to managing resources, the initial stages require significant inputs in terms of funding and time.

Another constraint is the research-oriented nature of fisheries line agency staff. Staff generally have higher education qualifications in the natural sciences. The promotion path in these organisations is often associated with the publishing of scientific research. In most cases, facilitating co-management is not considered valid research. Counterparts may therefore be unwilling to join activities of this nature. The fisheries line agencies themselves usually have natural science based research agendas and such research is often seen as the primary goal.

Earlier activities of MRF (Phase I) may have inadvertently strengthened this scientific orientation by providing training in biological and socio-economic survey methods. The emphasis on scientific approaches has, to some extent, been in conflict with the participatory management objectives of the second Component phase.

For users and government officers to take part and feel ownership in the co-management process, there is a need to reach some common ground in terms of the information needed for fisheries management. The process and the tools applied for collecting fisheries information must be consistent with the capacities of all co-managers.

Table 4: Reservoir managers' satisfaction and perceived benefits

|

Gender |

Satisfaction |

Benefit |

||

|

Viet Nam |

Thailand |

Viet Nam |

Thailand |

|

|

Male |

33% |

75% |

67% |

73% |

|

Female |

58% |

96% |

8% |

61% |

|

Total |

44% |

82% |

75% |

92% |

Table 5: Perceived benefits at reservoirs in Thailand

|

Benefit |

Much better |

Somewhat better |

No difference |

|

Knowledge sharing |

59% |

16% |

25% |

|

Improved communication |

32% |

48% |

20% |

|

Opinions are heard |

78% |

22% |

0% |

Scaling co-management

In large river basins like the Mekong, local management objectives may have large-scale implications. Similarly, large-scale management at distant locations may affect local resources and their management. Typical examples include management of migratory stocks. Local fisheries management may nurture part of the life cycle of a number of species in one location but water development projects such as hydropower dams block migration routes and negatively affect local fisheries in another location.

This adds a dimension to co-management: the need for vertical information flow and communication. Local co-management can play an important role in generating information that can be aggregated with information from other co-management activities in the basin as a basis for the formulation of regional management plans. This aggregated information should be communicated to the co-managers and used to increase knowledge and improve management at the local scale.

Capacity building

In Phase II, MRF developed several approaches to capacity building. One such approach is a regional training course in co-management (RTC) for central government counterparts and staff. This programme is conducted annually and emphasises participation, diversity, facilitation and adaptive management. Each regional course includes a follow-up workshop at national level where the participants from the RTC are invited to discuss their experiences with co-management and express their needs with regard to capacity building.

Another approach is to organize Joint User Government Officer Workshops or JUGOs. Each workshop focuses on a particular theme that has been identified by the co-managers as relevant to the management tasks ahead and emphasizes joint learning and creation of new knowledge through a learning-by-doing process. Part of the workshop consists of field visits to sites with successful examples of management that relate to the theme of the workshop. These workshops usually feature a facilitator as well as subject matter specialists from the central line agency.

|

Co-management is characterized by the sharing of decision-making in management and includes applied management instruments between government and users. Communication is seen as a cornerstone of the co-management process. |

Some conclusions

MRF's experiences with the implementation of co-management and fisheries information creation can be summarized as follows:

Information generation is a management function (sometimes called 'management research')

Information generation must have a clearly stated purpose and be consistent with the management objective

'Data-less' (not knowledge-less) management is a real alternative

To be effective, users should be involved in all stages of research and management options emerging from such research should be negotiated among those concerned

It is essential to select the information requirements according to the needs of the co-managers

There is a real danger that management information systems dictate who is included as co-managers

Fisheries management is managing people and their knowledge of resources

References

Coates, D. (2002). Inland capture fishery statistics of Southeast Asia: current status and information needs. RAP publication 2002/11, FAO, Bangkok.

Mattson, N. S., Balavong, V., Nilsson, H., Phounsavath, S. and Hartmann W.D. (2001). Changes in Fisheries Yield and Catch Composition at the Nam Ngum Reservoir, Lao PDR. In: De Silva, S.S. (Ed.), Reservoir and Culture-Based Fisheries: Biology and Management, pp 48-55. Proceedings of an International Workshop held in Bangkok, Thailand 15-18 February 2000. ACIAR Proceedings No. 98. Australian Center for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia.

Schouten, R. (1998). Fisheries. Nam Ngum watershed management. Asian Development Bank, TA-No. 2734-Lao.

|

[4] Formulated by Jørgen

G. Jensen, former Programme Manager of MRC Fisheries Programme. |