What is preventing the people directly concerned from participating actively in the programmes and taking charge of their own development?

This is the question that the authorities in charge of upland watershed development programmes must ask themselves.

Experience has already provided some answers:

The programme will have to take the necessary steps to supply components which cannot be obtained locally.

To do this, the following must be available.

Information, "animation", extension, training and education services.

These five activities are inter-dependent and complement each other.

Because of their isolation, the limited opportunities for exchanging ideas and the traditional constraints to which they have been subjected, the mountain people have evolved very slowly. Development requires the use of more intensive production methods, such as those developed by modern science, research and experiments.

(Information, "animation" and motivation has already been dealt with in Chapter 9).

The principles of extension have been known for more than a. century, however, it is only over the past few decades that special services, termed extension services, have been set up in many countries.

The role of these services is to provide the rural people with the knowledge they need to be able to increase their production.

The essential difference between education and training provided in the schools, and extension, lies precisely in the fact that the "knowledge" is "brought" to those who need it.

Formerly, in most developing countries, farming instructors were merely technical advisers who conveyed instructions from the ministries of agriculture to the farmers and supplied them with certain inputs (seeds, pesticides, tooling).

Later, first community development and then rural "animation" were instituted to motivate the rural people and provide basic training. Sometimes, the technical services (agriculture, livestock farming, water and forests, public health, etc.) asked the community development authorities to motivate the people, to prepare them, so that they would be receptive to certain "extension campaigns" which were of major importance to the country (reafforestation, control of certain cultivated plant diseases, hygiene, small barrages, etc.). The community development officers dealt with motivation, while the technicians of the relevant services imparted the methods and new techniques. Most of these campaigns were successful.

Today, the extension field worker is often also the "animator".

Frans L. Sohmidgall points out that "with the adoption of the principles of community development and rural animation, the methodology used in extension work has improved considerably".

| "Extension has become an educative action for the rural people, especially as regards the process for the adoption of technical, economic and social changes as well as peasant organization." |

Furthermore, the approach is an integrated one, i.e. the extension agents address farmers as well as the other members of the family, women and children. This is why female agents must form part of the extension team.

Extension agents must be versatile, for the sectoral approach has long been abandoned. In theory, a single agent (or a team consisting of a male and a female agent) is in contact with the people for matters concerning both crop and livestock farming (see Chapter 8) as well as forestry.

This does not mean however that extension agents are omniscient. They must be supervised by specialized technicians who advise them, prepare technical data for each activity, provide "on the job" training and help them to solve the many problems that arise.

Over the years, extension services have accumulated a considerable amount of experience and their methodology includes a wide variety of methods for motivating rural populations and conveying the knowledge necessary.

The agent's first contact with the area assigned to him usually takes the form of a popular general meeting.

The second phase will lead to consultations (hearings), in small groups, if possible at CAG (see diagram section 9.4.2) level if the community is well-structured. Then, through individual visits, the agents get to know their sector, its human potential and its resources. During discussions, they can already identify certain needs and draw up programme proposals, These proposals will be submitted to the technician supervising and controlling the agents. He will, in turn, pass all the proposals on to the person in charge of preparing the programme, to enable him to plan all the programme activities and draw up the list of inputs required.

Technical data sheets will be prepared in collaboration with all concerned.

Other extension methods include: method demonstrations, result demonstrations, farm visits (erosion control), reafforestation, grassland and fish culture operations etc.), small working and discussion groups, consultations in the agent's office ' etc. The most commonly used audio-visual methods are:

Some governments have prepared radio or even television programmes on extension, and these programmes are followed by listening groups or clubs which are organized by the agents or local leaders.

In some countries, training centres have been set up. They are supplemented by demonstration farms and constitute excellent extension tools. Groups of farmers, women or young people can attend for periods of a few days.

The success of the programmes depends largely on this personnel, on their qualifications and number. This is stated on several occasions in this guide. It can never be repeated too often.

There are usually three levels of extension personnel: the extension worker, the technician and the senior extension officer.

The extension worker at the village level works directly with the crop and livestock farmers and forest users. He (or she) must be modest, devoted, good at establishing contacts with the rural people and must inspire respect and confidence.

They must like living in rural areas and be prepared to make the efforts required to travel on difficult terrain, most often on foot and to carry out demonstration, must always be available to meet the farmers' personal schedule, and must speak the local language. It is sometimes an advantage if they come from a neighboring region instead of the sector to which they are assigned, but in other cases ' the opposite is preferable. This will depend on the individual.

Agents assigned to upland watershed areas must come from mountain zones and must be well-acquainted with the characteristics of these areas from childhood. After a trial period, it may be necessary to switch the agents round.

Some programmes have used "model" or elite-farmers to spread the action of the extension agents. In most cases, however, this method has failed, since this "privileged" category was rejected by the communities.

The extension agent must of course be school-trained. He will also have to pursue basic training on a continuous basis. Two or three years of secondary school are desirable, but this will depend on the salary provided. If it is low ' the level of recruitment will also be low.

A few countries provide vocational training for their agents at a national level, in schools and centres spread over the different regions. Elsewhere, they are trained "on the job" by their supervisors. Often, they are recruited and receive special intensive training geared to programme objectives.

It goes without saying that training for field staff should be essentially practical and that when they are selected, preference should be given to those most gifted for manual work.

When agents who are already employed are detached or transferred to development programmes in upland watershed areas, they must be given refresher courses to prepare them for their new tasks.

Much is required of extension agents, and their material conditions are most often lower than they should be, to encourage greater efficiency. Salaries, as well as job security and the productivity bonuses (always difficult to calculate) provided by some programmes, always play a major role. But there are other problems involved: means of transport, housing (the field worker must live among the people he is helping ) advising the agents' families.

At the intermediate level, extension technicians are usually permanent government employees. They are trained at national centres (specialized agricultural schools, secondary level agricultural schools) and their agricultural studies take two to three years, which follow two to three years of general secondary studies. They too will have to be given refresher courses adapted to programme activities. It is too often noted that they lack practical preparation. (In some countries, they are classified as technical assistants).

At programme management level, senior extension officers are university graduates with a vocation for this activity, or speciality. They will also have to have vast practical experience to be able to show the technicians and agents how the work is to be carried out. In addition, they will take part in planning and programming the activities. They are responsible for estimating input, tooling and equipment requirements, as well as organizing transport for the supplies within the time allowed.

(Comment: Foremen and team leaders are not included in this category of extension . personnel, for they are not involved in training).

The extension agent and the farmers should meet weekly, either for group activities or individual visits. Intermediate level and senior officers should also spend most of their time in the field, not only for the purpose of carrying out "inspections" but to take an active part in the work.

Staff density is an important factor. The higher it is, the more rapid the results. Experience has shown that for supervision to be effective, a field agent should not be in charge of more than 200 farmers. In mountain areas, where movement is made difficult, the density should not be lower where intensive action is involved. In addition, there should be one technician (technical assistant) for every 4-6 agents and one senior officer for every 4-5 technicians.

Audio-visual material (see section 10.1.2) must be suited to local conditions. Local conditions in upland watershed areas mean: a hilly mountain zone where access to villages and farms is difficult and where electricity is not often available.

Excellent results have been obtained at the beginning of some programmes, before the people were able to construct simple shelters, through simple meetings held "under the tree".

Simple flannel boards, which are easily made with slightly woolly material, two sticks, strong paper and small pieces of adhesive tape (e.g. 'Velcro') which are stuck on the back of texts and pictures (the type of "sand-paper" generally used is not adhesive enough for outdoor classes) are extremely useful; they are cheap and even withstand wind.

Each agent must possess a complete set of tools suited to the work he has to do.

In mountain and grassy zones, levels, scything and pruning instruments and woodcutter's tools are indispensable.

They must also have small quantities of inputs (seeds, fertilizer, pesticides, etc.) for demonstration purposes.

The members of the rural communities need training in many fields, including vocational training.

As pointed out in the first part of this guide, the use of primitive farming systems and techniques are particularly responsible for the degradation of upland watershed areas. Other systems and techniques have been developed, but they are still unknown to isolated populations.

The primary role of the extension officer is to bring knowledge to the farmers. Their job is not easy, since farmers all over the world are attached to their habits. It takes generations to convert a "peasant" into an "agricultural entrepreneur", the former being a routine farmer, set in his ways, and the latter, someone seeking every' possible means to obtain the maximum yield from his land, water, animals, plants using all the methods and inputs likely to increase profitability. Both must try to maintain the balance of the natural resources which provide their subsistence.

| Before the stage is reached whereby those concerned support the programme, i.e. decide to participate, the extension agent will have to inform - motivate - convince, a nd at the same time, train i.e. transmit, pass on his knowledge and know-how. |

In the case of development of the areas which are threatened by erosion, the programme must cover all the techniques proposed by water and soil conservation experts, in particular, anti-erosion planting techniques, including intensification of forage production to compensate for the closing off of forest rangelands and pastures.

In addition, the people must also receive training for their role as members of the community.

The new structures and organizations require that each member be specially prepared to recognize the aims, limits, means, different structures and the way they operate and above all, their own duties and rights.

The members who will be elected to councils and committees will have to learn to assume their roles.

Training will be essentially practical and will be provided while the activity is in progress. The agent in charge will prepare material which is as simple as possible and will show imagination by taking examples from local everyday life.

It could be used to develop a democratic spirit at the grassroots level. A collegial spirit must develop within the committees.

The members of the community must learn to take part in discussions.

The young will learn to respect the trees, soil, water, from an early age.

The simple clubs and other associations can serve as an excellent basis for training future popular leaders.

This type of training is not often provided.

What is important, is that after they have taken specialized training, everyone with a role to play in rural development, every expert (forester, rural, agricultural, engineer, animal husbandry officer, Brazier, economist, extension officer, etc.) be given further training in integrated rural development.

Every "grande école" seeks to develop a "school" spirit among its pupils, and every "constituent body" of experts, an "esprit de corps" among its members.

| This partition seriously hinders integration of activities at all levels. |

The following solution to the problem was proposed by high-ranking participants at a seminar held at the Rural Development College (RDC) in Denmark in 1973:

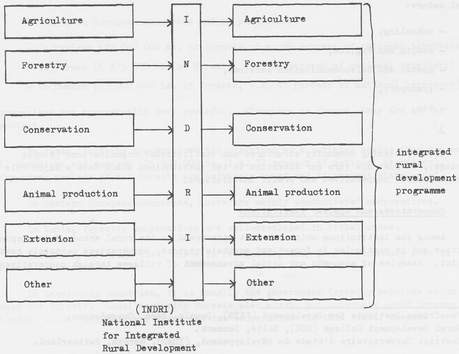

All the specialists working in rural areas have to undergo joint training at a National Institute for Integrated Rural Development (INDRI), which could also act as a data bank and research centre.

Diagrammatically and in brief, this can be shown as follows:

It goes without saying that this extra training could be held at the higher and at middle levels.

Some international institutes hold courses on all aspects of rural development, right up to ministerial level.

Technical backing here means the team of experts, engineers and technicians in different fields, in intermediate and high-level posts, who are at the disposal of the field staff to provide them with and explain the technical data, show them how to implement the work, provide them with inputs and assist them, if necessary. Their role also includes monitoring, to make sure that the work has been implemented correctly and in the time allowed. They must also pay attention to feed-back of information for the re-orientation of operations.

It is thanks to this technical backing that field agents can be considered versatile.

This extension system has produced excellent results in Malawi, in particular.

This section of the guide would be incomplete if no mention were made of the other services which play a part in social development, in particular services of a social nature:

After reviewing community structures and institutional organizations (simple groupings), we must now turn our attention to two institutions which have a major role in development: cooperatives and credit institutions.

Among the institutions which are most widespread in the rural areas of developing countries and in particular in forest and mountain regions, cooperatives certainly head the list. Examples of economic and social advancement of villages through cooperatives, abound. The example is often cited of a village in Bangladesh, which in spite of numerous obstacles (poverty, traditional and religious taboos, superstition, etc.) succeeded in trebling its production in the space of 15 years, by intensifying and. Diversifying its crops, thanks to cooperatives.

In spite of the errors committed, which caused considerable harm to the cooperative movement in some countries, the very principles of cooperation, laid down by the pioneers of the movement in the middle of the 19th century, are still valid. It must be acknowledged that these principles are more easily complied with in developed than in developing countries.

Cooperation, in the general sense of the term, has always existed wherever men, conscious of their weakness in the face of all the problems that assailed them, combined their efforts in all possible spheres. Forests and water were most often the subjects of this type of cooperation and mutual aid; clearing, the construction of irrigation systems (e.g. in the Alps), the processing of dairy products (cheese), the construction of shelters or huts, mutual aid in the case of sickness or death, savings, were among the first targets chosen by members of the first cooperatives.

According to a survey conducted in 1976, forestry cooperatives, more or less well-organized, exist in about 30 countries.

In Northern European countries and in particular;

cooperatives are economically very powerful. Elsewhere in Europe, they are not as important.

In Japan, forestry cooperatives are organized on a national scale; they are very well organized and managed (25 000 000 ha. i.e. 70 percent of national territory). Fifty-seven percent of all forests are privately owned and 11 percent state-owned.

In Eastern European countries, there are mainly woodcutters' cooperatives.

In India, forestry cooperatives are well-developed in tribal zones.

Elsewhere, although their value is recognized, they play a secondary role in forestry activities.

In developing countries, it is usually the government forestry services which manage the forests. Local community forests also exist, but privately owned forests are not often found. This is why there are few cooperatives in this field, despite government encouragement. In Malaysia, the government grants forestry concessions and tax exemptions to cooperative federations. However, "vertical" integration of these institutions is difficult, since there are insufficient numbers of qualified people to manage them, lack of funds and also because the primary cooperatives enjoy their independence.

Nigeria and Fiji plan to introduce cooperative institutions in their agro-forestry systems ("taungya" system).

The potential for cooperatives in forest areas is nevertheless enormous, These institutions can adapt to almost all circumstances, from the mere collection of secondary forest products, to the largest industrial-type enterprises.

Both small and medium-size forest owners and users have joined cooperatives to benefit from the following: protection against fires; disease and parasite control, closing off and management of forest zones; felling, pruning and transportation; processing timber (sawnwood, veneering, slicing, etc.); reafforestation (throughout the world); preparation and marketing of charcoal (in Morocco, inter alia); inputs and tooling; combined use of forest patches and forestry work (woodcutters' cooperatives), savings and credit, etc., etc.).

In mountain areas, where activities are varied (agriculture, livestock raising, sylviculture, fish culture, water and soil conservation, irrigation, etc.), the villagers often have to set up milti-purpose (e.g. agro-forestry or agro-pastoral or sylvo-pastoral) cooperatives.

Cooperatives also have their role to play in soil and water conservation and protection of the natural environment. On this subject, the authors of the study conducted by the Plunkett Foundation, which was mentioned above, consider that cooperatives can play a major role in areas where there is a majority of small farms and where the forest is threatened by millions of small farmers and artisans. Through cooperation, overall plans can be drawn up for management and planned use of natural resources in the interest of all, but with provision being made for the needs of farmers, Braziers, artisans and artists working with wood, firewood collectors, etc. Agreement of all concerned on locally established regulations is less costly and causes less friction than the enforcing of laws by government authorities.

This system, however, is valid only when the forest and lands to be managed belong to the local communities or to individuals and in so far as the training and level of evolution of the members of the communities allow them to manage their cooperative and accept the discipline required.

Gully control, construction of protected waterways and other structural conservation measures require sound training and demonstration for the farmers to carry on with the restoration work.

|

UNIVERSALLY RECOGNIZED PRINCIPLES

|

The essential differences between cooperatives and Share Companies Ltd. are as follows: the former are made up of "persons", while the latter are composed of share-holders; in the former, participation or membership, is related to the conditions set out in the statutes, in accordance with the law (for example: the member must own or work a farming, forestry or agro-forestry concern; must live in the area in which the cooperative is operating), while in the latter, anybody can acquire an unlimited number of shares.

In almost all countries of the world, cooperatives have government support, because, in spite of their shortcomings, they represent the socio-economic model which is most widespread and the one which is best accepted by the people. The aim of governments is to encourage, rural communities first of all, to manage their own affairs, be it production, processing, and marketing of any agricultural crop, livestock farming, forestry or the provision of inputs and consumer goods.

Dr. G. Fauquet, who is an expert on the subject writes

|

"The prime objective of the cooperative institution is to improve the economic situation of its members; but, by the means that it employs, by the qualities that it demands of its members and develops in them, it aims at and achieves much more. The aim of cooperation is therefore to make them aware of their responsibilities and stand together, so that individually they may achieve a full personal life and together a full social life." |

A former director of the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) has pointed cut the educational role of the cooperatives in the following sentence: "It has been said that cooperation is an economic movement which calls for educative action. It could just as easily be said, by inverting the sentence, that: 'cooperation is an educative movement which calls for economic action'."

At the moment, there are millions of cooperatives in the world and their members number hundreds of millions.

Roughly, it is as follows:

Study circles combined with literacy programmes, if necessary, so that all the members may be in a position to take charge of their own affairs. When groups like those cited in section 9.6.2 form a cooperative ' this stage can quickly be cleared.

Definition of the aims of the cooperative; inventory of the resources required; preparation of the by-laws; fixing of the value of the authorized share (often, at this stage, in the villages, the members of the cooperative are beginning to build their own premises for their meetings).

General constituent assembly.

Official procedure for the registration of the cooperative.

In principle, it is members' contributions, especially the shares they have subscribed, which form the financial basis for its operations. Even in developing countries, where the members have very limited means, some cooperatives have managed to advance rapidly through their own efforts (e.g. section 9.6.2).

The surplus can be converted into shares instead of being refunded to members, provided that they so decide at their annual general meeting.

As an incentive, governments usually grant credits to cooperatives which have given proof of their viability, for specific purposes; they are also exempt from most taxes.

The problems to be faced by all enterprises, be they cooperatives or not, are always of a human and material nature: honesty of those in charge, fluctuation of prices, losses during storage and handling, etc.

In some cases, governments assigned unpopular tasks to the cooperatives (e.g. compulsory grouping of farms) ' which is in contradiction to the principles upon which cooperatives are based; the failures which resulted forced the authorities to close down the cooperatives.

But, there are other barriers, mainly of a moral nature.

People living in isolated areas do not easily place their trust in those who are not members of their families. A minor disappointment may be enough to cause a member to cease to participate in meetings and activities. When a problem arises, few members have the courage to bring it up and try to solve it, in spite of the powers that the law and the by-laws allow them; they prefer to stop cooperating.

The cooperatives also have their share of enemies, mainly among the traders with whom they are competing.

This means that new cooperatives need the constant support of competent agents to defend them and the backing of the authorities.

It is above all in the fields of education (principles, organization, management, rights and duties, etc.) and personal and vocational training for members that help is essential.

It would be a mistake, however, to grant aid on too large a scale to new cooperatives. It is essential, first of all, for members to show their determination to cooperate and succeed. Afterwards, credits and even subsidies to allow activities to develop more rapidly, could be granted and, if necessary, access to more advanced technology (sawmills and other wood-based industries, animal-based industries, agro-industries, processing of goods for export, etc.).

If part of the managers' salaries are subsidized by an agency specialized in granting aid to cooperatives, on the basis of a scale, becoming degressive annually, new cooperatives are thus able to benefit from the services of qualified managers from the start.

The authorities, who own most of the commercial forests in some developing countries, could allow the forestry workers' cooperatives to exploit and manage them.

Cooperatives are found in all fields of economic and social lifer agriculture, livestock farming, forestry, handicrafts, provision of inputs, housing, savings and credit, social security (mutual benefit insurance).

Motivation for the promotion may also be entrusted to extension workers and group leaders. Very quickly, however, the help of specialists in cooperative management must be obtained, to cover all the technical and economic aspects (management, book-keeping, supplies and marketing, etc.), which are beyond the competence of field agents.

A certain confusion has sometimes been noted in the minds of the local elite and popular leaders as regards community development and cooperatives. The difference between them lies in the fact that the aims of cooperatives are social and the activities used to achieve them are of an economic nature, while community development seeks to achieve its objective through "self-help".

Both the community structures and the cooperatives are extremely useful for development; they complement each other. Community development prepares an environment which contributes to the development of cooperatives, while the cooperatives provide the community with the prosperity and the material means to achieve the social objectives.

When a cooperative is evaluated, it is not sufficient to analyze the balance sheet and the operating account; the system of operation of the institution must also be examined and the extent to which members participate in decision-making and take an active role in activities must be established.

The existence of a cooperative sector side by side of the public and private sectors provides a check against the injustices to which both producers, consumers and users of services, alike, could well be the victims. In view of this, it is essential that the cooperative movement be very well structured from the village level right up to the national level (cooperative unions and federations). "Horizontal" integration (between cooperatives pursuing different aims, at the same level) strengthens the movement in relation to the other sectors of the community.

Almost all the examples cited in Annex II mention credit as one of the most effective tools for the promotion of development.

This is not false. Nevertheless, this tool must be used advisedly and the candidates for credit must undergo serious preparation prior to receiving loans.

In almost all developing countries, the economically deprived worsen their condition still more when they need money, since their only possibility is to go through money-lenders. Interest rates of the order of 5-10 percent per month are frequent.

Money-lending is extremely widespread in upland watershed areas because these areas are also the most deprived. At sowing time, farmers buy seed, on credit, from local traders - money-lenders. Livestock farmers obtain credit to buy animals. During the "lean" period or "hungry" season, the people fall into debt with merchants to buy essentials for their subsistence. One of the main causes of their falling into debt lies in the celebration of marriages and funerals, since, for the sake of social standing, they spend far more than they can afford.

The first type of credit to be granted the active population is:

It often happens that after the crop or livestock farmer or forest user have mobilized all their own resources (land, water, work, capital) for production, they cannot use the inputs recommended by the extension agents, due to lack of resources. This is when credit becomes indispensable for development.

A few guidelines for credit programmes:

| Credit is only one among other tools for the development of production; it must not be abused, but must be placed in a context in which its effect can be fully felt. |

| Credit must not precede, but must be a follow-up to animation activities and must be an integral part of extension programmes. |

| It is vital for the farmers to be informed and trained in order to be able to distinguish clearly between gifts and grants on the one hand, and assistance in the form of credit, which they will have to reimburse, on the other. |

| All available financial resources must be assigned, on a priority basis, for production purposes. |

| Cash purchasing of material and products for current use on farms etc, must be encouraged as far as possible. |

| It seems advisable to link credit to marketing; automatic deductions at source are however not advisable. |

| Every effort must be made to strengthen the discipline of reimbursement. |

| Rural savings must be encouraged. |

| It is not enough to provide credit at reduced rates of interest; the governments or the upland watershed development programmes must set up or reinforce the technical services that the farmers need to obtain maximum benefit from borrowed capital. |

| In the initial stages, it seems preferable to have a single rural credit agency operating at local and regional level. |

| The problems posed by savings, distribution and control of credit are considerably simplified when the institutions are decentralized. |

| It is preferable to grant loans in kind to farms and business concerns that are beginning to produce for the market and to reserve cash loans for farmers who are more economically advanced. |

| When they are part of integrated action, credit operations must be centralized by the specialized institution dealing with the management of funds, but each technical department must play the role in which it is specialized. |

| "Supervised credit" is a method of rural promotion which closely combines financial aid and technical assistance and which also rests on cooperative action. |

| Where extension has begun successfully, credit must follow without delay if the advantage gained by the first efforts are not to be lost. |

| The credit and extension services must be closely integrated. |

| "Directed credit" is the type used for the promotion of specific activities. |

| Credit is closely related to the land tenure and to community development. |

| Recruitment of staff to take charge of agricultural credit must not only be based on the level of vocational training; candidates must also undergo psychotechnical tests. |

Rural development programmes in upland watershed area management often have their own revolving fund to provide credit to the people participating in the operations. This is the case in Colombia, in particular (see Annex II, page 3).

In other cases, guarantee funds for small-scale agricultural credit were set up to cover the risk run by commercial banks when they grant loans to small farmers. This is the case in Bangladesh, where the "guarantee-cum-risk fund" guarantees the loans granted by the Central Bank to participants in integrated rural development programmes.

Efficient administration of a revolving fund first of all requires a credit committee, composed of programme specialists, chaired by the programme director. A few village representatives should also be asked to participate. The main role of this committee is to decide on loan requests (grant or refusal) and to rule on disputes before starting legal proceedings.

Credit operations consist of two distinct phases:

First phase

Second phase

The files will be prepared by the field staff with the help of the technicians and the senior staff. All the specialists concerned will be asked to give their opinions.

The actual management of funds, i.e. payment of the sums granted or delivery of goods (inputs, in general) on credit, followed by collection of interest and reimbursement, is costly, when the total amount of credit granted is small and especially when the number of those who fail to meet their commitments, against which legal proceedings must be taken, is high.

It is therefore recommended that this work be assigned to credit institutions already established in the region (branches of Agricultural Credit offices or Development Banks, etc.), which have an expert staff and the necessary facilities at their disposal.

Technical backing is vital. This is why staff density must be adequate.

A certain number of principles and regulations must be respected if the working capital fund is to operate properly and if problems are to be averted:

|

The same person must not be in charge of, on the one hand, the handing over of funds and the collection of interests and reimbursements, and, on the other hand, of providing technical supervision and advice. |

Since material guarantees are not available, the question of the morality of the person requesting the loan is essential. For members of groups and cooperatives, the principle of joint responsibility will be used.

Manuals, giving details of all the operations, will be prepared. They will also be used for training everyone with a role to play in fund activities, be they recipients, members of staff, or members of the credit committee.

Only after the crop and livestock farmers, artisans, etc. have achieved substantial improvement in their income through increased production, will medium and long-term investments for the improvement of housing and other factors related to standard of living be considered.

Often, it is on the occasion of marriages and deaths that the most deprived rural people feel the need for credit. It is clear that development programmes in upland watershed areas cannot directly meet these needs.

Mutual aid societies must therefore be set up.

Lack of material means and initiatives as well as the fact that they have little contact with neighboring areas and the rest of the country are the reasons why isolated mountain people do not often dispose of the equipment and infrastructure needed for development. The problem is made all the more complex, as the settlements are scattered over a wide area.

Urban settlements grew up where paths and roads crossed, to facilitate local trade. Some developed into administrative centres.

Where the development of a region is concerned, a distinction must be made between at least two levels:

In local administrative centres, in addition to official offices, there is usually a primary school and a market place. This administrative centre must attain a certain size to justify a post office being provided and a telephone and telegraph system being connected.

Sometimes, villages which are not promoted to the rank of administrative centres are provided with schools by the religious communities; the buildings are rudimentary, are built by the faithful and the teachers who, although devoted, are badly prepared for this task.

More complete facilities and equipment are obviously necessary to promote development. "More complete" does not mean "more sophisticated". What is necessary however is a solid, permanent base of operations, which could later be managed by the people themselves.

Basic facilities required are: rural development centre; market, training centre for crop and livestock farmers, foresters, artisans, activities for women, youth clubs, etc.; dispensary, rural school and the cooperative building.

This is also sometimes called the rural promotion centre.

Whether it is located in large villages or in the administrative centres closest to the field of operations depends on population density and the relief of the area and on the material means and staff available.

It is above all a meeting place. Meetings of the Community Councils, their Management Committees and Sub-Committees (see p. 69) or any other development institution pursuing the same objectives are held there.

The important thing is that these centres be fully utilized.

When upland watershed management programmes start, they could also be used for other purposes (training, consultations by traveling doctors and nurses, etc.) until the other buildings are completed.

Standard plan for a rural development centre:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Markets play a considerable economic and even social role in rural communities. Not only are they places where goods are traded, but where contacts are made and ideas exchanged. They must therefore be set up on sites that are pleasant, sheltered and well-equipped (first with drainage and sewerage, a slaughter house, then warehouses, silos, cold storage facilities, post office, bank etc.).

Financing could be provided through a loan on favorable terms, reimbursable through low taxes to be paid by traders and other users of the facilities.

Upland watershed development programmes cannot do without the help of marketing specialists, for it is not sufficient to increase output; it must also be sold at prices which are proportionate to the efforts and sacrifices made to obtain it.

This centre, which is intended for crop and livestock farmers, foresters, artisans and members of their families, will be set up a certain distance away from the rural development centre so that demonstration farms and handicraft ventures may develop around it.

Housing facilities for the technician in charge of the centre must not be forgotten.

On the technical plane, this centre must be the prime mover of integration, the catalyser of development activities.

Successive visits by different specialists: foresters, agricultural engineers, horticulturalists, those in charge of women's and youth clubs, advisers on cooperatives, etc. could be organized in accordance with a detailed schedule drawn up jointly by all those concerned at the beginning of each year, as is the case at the Farmers' Training Centres in Kenya and Uganda, for example.

At first, sessions will last one day. However, as the programmes develop, dormitories and simple kitchens will have to be set up to allow courses lasting several days to be held. In some countries (Kenya), participants have accepted to pay their own accommodation and food expenses.

The demonstration farms must also be involved in increasing selected seed production, in producing plants in nurseries, in breeding animals for reproduction, and swarms of bees, etc., as well as in experimenting techniques and methods in relation with programme objectives. The seeds, plants and breeding stock will be handed over to the best crop and livestock farmers and forest users in accordance with a contract ensuring propagation of new varieties and breeds (e.g. return of certain quantities of seeds or a certain number of animals).

One of the primary needs of members of isolated communities is to be cared for when they are ill or injured.

The prerequisite laid down by official public health authorities or hospitals located in regions adjoining watershed management areas for assistance for their doctors or male or female nurses is usually the construction and equipment of a building, i.e. a dispensary. In many cases, the equipment is donated to the community.

These dispensaries must be served regularly by a devoted and competent staff. If costly medicines, which are beyond the patients' reach, are prescribed, they must be subsidized so that the most deprived can benefit. They, in turn, contribute a symbolic sum. It would be a mistake to provide the medicines free of charge.

In some rural development programmes (e.g. in the People's Republic of the Congo) the villagers used part of their increased earnings from new activities to set up a small village pharmacy. Certain members of the community were trained in first-aid.

|

To teach, to train, is to enable the people to take charge of their own development. The World Bank considers this the most important field of activity in human development. This is the prerequisite for modern development and industrialization because it increases the level of awareness, develops a person's capacity for learning, adaptation and innovation. |

Teaching in rural schools must be based on the study of the environment and on the needs of the pupils when they become adults.

Prerequisites are:

The best motivation lies in the enhancement of the value of farm work.

A new "generation" of primary school teachers must also be prepared.

Rural people have often sacrificed a great deal to build schools at their own expense and employ school teachers.

The people of the isolated watershed mountain areas cannot be expected to participate in the economic and social development of a country unless they are taken out of their isolation.

To do this, roads, paths, bridges and other civil works must be built. Rapid means of communication (telegraph, telephone, postal services) with the outside world are absolutely essential.

A good network of roads within the area facilitates movement and transport. Logs and sawnwood are sometimes sent down to the valleys by cable-car.

The road network must be designed bearing in mind forest exploitation requirements and the needs of the local people. It must be simple, easy to maintain and respect the natural environment.

The opening of new roads has contributed to the economic development of extensive forest regions (e.g. in the coffee producing regions of Ethiopia).

The main problem involves the level of technology, taking into account the need to create new jobs. This has already been dealt with in chapter 6.6.

In addition to being aware of and using inputs (improved seeds ' fertilizer, insecticides, etc.), two factors contribute considerably to making efforts more profitable:

It is through technological advancement that the industrialized countries produce more than they need.

Experience has shown that it is preferable to proceed in stages:

Example for agriculture, forestry

| First stage:

Improving, perfecting hand tooling. |

Remarks:

Advantages: inexpensive, can be manufactured in the country and likely to provide jobs; can be repaired locally in the area in which the programme is underway by local artisans who have been trained and equipped for that purpose. |

| Second stage:

Introduction of animal traction, even in mountain areas, with the aid of winches, pulleys and towpaths. |

Advantages: no need for complicated and costly equipment which would be difficult to repair locally - no need for fuel (always costly). The draught animals must be trained and harnessed. Tools suitable for this type of traction in mountain areas must be designed and made (ploughs, hoes, ridge-ploughs, carts, etc.) and operators must be trained. |

| Third stage:

Introduction of cultivators, tractors motors, etc. |

Advantages: powerful, relatively mobile (some models); the cultivator seems to be the most

suitable at first; it also presents the advantage of not compacting or damaging the soil.

Disadvantages: fuel costly and not always available. Qualified staff necessary for maintenance and workshops for repairs; spare parts expensive and not always available; heavy equipment destroys soil structure. |

The degree of technology required for treating and processing forestry, crop and livestock products varies considerably. In mountain areas, an axe (squaring off) is still sometimes used for hewing, and lengthwise sawing is done by hand. The number of small artisanal sawmills, however, is rising. On the other hand, there are fewer industries involving slicing, rolling off, the preparation of plywood, fibreboard, pulping, etc.

In pastoral zones, livestock produce can be processed, either using primitive technology, usually for local consumption, or using industrial methods for the supply of urban and industrial centres. The same applies to agricultural produce and the products of tree cultivation, especially as regards the preparation or milling of coffee from the fresh berry of the coffee tree.

Level of technology is also important for non-agricultural work, such as handicrafts and household activities. In handicraft work, more advanced technology results in increases in both productivity and profitability; in household activities, it saves time and effort.

In view of current chronic unemployment or under-employment in mountain areas, it is preferable to choose a level of technology which requires large numbers of workers, but which helps to improve the efficiency and quality of the work.

|

On the subject of transfer and planning of technologies, more common sense and flexibility is called for. |

All programmes involving the improvement of technology must include a section dealing with "training".

In any case, as soon as capital goods are purchased, financial measures must be taken to set up a replacement fund. Otherwise, and this is most often the case in developing countries, especially when a donation is involved, it will not be possible to replace the equipment when it has gone out of service. The degree of technology regresses.

Recipients, private individuals, cooperatives or communities must be taught to save (through a savings account, for example) part of the extra income they earn through the use of the equipment in question.

When, in spite of intensive utilization, the available land does not allow the local people to attain a satisfactory standard of living, other sources of income in addition to agriculture, forestry and livestock raising must be found, to be used either as a secondary or main activity.

Wood processing industries cam make a considerable contribution to development in upland watershed areas.

"The direct and indirect 'off-farm' employment created by forest-based industries should help in siphoning off some of the population pressure on the land resource". "Until recently, exports of wood from developing countries have been in the form of unprocessed logs. Thus, it has been estimated that if the 49 million cu.m. exported as logs had been processed in the countries of origin, this would have brought them another 82 000 million, as well as several hundred thousand man-years of employment." "Factory design should be adapted to circumstances of abundant unskilled labour, but should also take account of scarce capital and managerial talent. Fortunately, sawmilling, which is the most widespread form of processing and likely to remain so in developing countries at least, has a very flexible technology. It cam therefore be viable over the whole range of scales, from a craft to a quite sophisticated industry."

The preparation of charcoal in mobile furnaces, which provides a better yield, is also am economic activity which is worthy of consideration as a means of putting small logs to good use.

Cooperatives are expected to contribute substantially to promoting these activities in developing countries; they already play am important role in many industrialized countries.

Other secondary forest products supply industries and small-scale local trade (see p.37 ). At the present time, some of these products have regained status, after having been seriously threatened by synthetic materials for several decades.

Large areas of upland watersheds are without forests, however, either because of the altitude, or as a result of deforestation.

The know-how of the mountain rural people continues to be extremely valuable. Men and women, young or old, who have inherited artisanal or artistic techniques from their parents are found almost everywhere. Some weave (cotton, wool, sisal), others work horns, hides or skims. Pottery making and other artistic activities bring extra income. Tourism also provides many jobs.

Labour is available, but is badly utilized. Organization, of raw material supplies, work, marketing and credit, is lacking. Sometimes, a simple calculation shows that income just covers expenses and there is no surplus to pay for the work. On other occasions, the artisans are exploited by the people who provide work.

For artisanal activities and small-scale industries to develop, the following fundamental conditions must be met;

These activities provide the cooperatives with wide scope for action.

It is in the interest of development programmes in upland watershed management to promote these activities, e.g., by providing experts and granting credits and subsidies.

Transfer of populations may be avoided if handicrafts, small industries and tourism are developed.

Often extension and "animation" do not suffice to obtain the spontaneous participation of the people directly concerned by the development programmes. Until the activities undertaken produce substantial improvements in yields, material encouragement constitute the best incentives for participation in mountain watershed management.

Incentives are justified for the following reasons:

Incentives could take a material form, i.e. tax exemptions, tax reductions, preferential rates, temporary jobs, or simply services or advice.

Certain work, which is in the general interest (holding back rivers, controlling falls, construction of access roads, etc.) is often undertaken by governments or the development programmes; the workers are paid salaries. These temporary jobs are greatly appreciated by those who see their income drop as a result of the management work.

The key to the success of a conservation project in Jordan was the use of incentives and adequate staffing for motivation, extension and training.

On the other hand, when certain improvements benefit one person alone, it is normal that the cost of the improvements be borne by that person. The incentive could, perhaps, take the form of credit on favorable terms and expert advice; compensation will be made for temporary harvest losses.

These encouragement or incentives, may be considered under three main aspects: purpose, type, mode of distribution.

Incentives are meant to:

This is a very important aspect, which is sometimes the subject of controversy.

They include:

services:

|

The use of incentives or encouragement must not cause jealousy and discord among members of the community and must not turn them into permanent recipients. |

As far as individuals are concerned, distribution must be limited to the strict minimum; e.g. for clearly defined management work or to recompense the poorest villagers for their participation in a community activity.

It is advisable to distribute incentives:

The ideal situation would be to have a community which were sufficiently wellstructured, organized and trustworthy to be able to manage and distribute the incentives under the supervision of official or programme authorities. (Distribution of WFP food rations in Ethiopia is done this way). It would be a good thing if government or programme authorities and the community leaders could accept joint responsibility for this distribution.

Attention must be paid to the negative effects of wrongly used incentives. Confusion between economic encouragement and incentives, on the one hand, and "gifts" or "donations", on the other hand, must be avoided. A salary is a fair compensation for a job done.

The reasons why entire programmes or certain sectoral activities succeed or fail deserve to be rigorously analyzed and reviewed so that repetition of errors may be avoided.

Successful ventures to be mentioned include the organization of the associative type small farmers and landless farm workers groups which were set up in Bangladesh, Nepal and the Philippines within the framework of the FAO/ASARRD programme.

Failures include numerous "standard" type cooperatives which did not manage to obtain the support of the poor, as well as some credit programmes, a large number of whose loans failed to be reimbursed because of lack of education on the part of recipients and insufficient training on the part of agents in charge of operating the funds.

All the projects and programmes which provided the basic information for this guide mention the lack or inadequacy of available data for the preparation of plans and programmes and the development of techniques and methods.

The gaps are particularly serious on the following points: traditional customs, structures and institutions of the mountain and pastoral people of the developing countries; extension; cooperatives; credit; facilities and equipment for development; technology and employment; incentives.

Available data must be placed at the disposal of everyone working in mountain areas in developing countries. The modern methods available to documentation centres and data banks (especially microfilms) allow those who need information to obtain it without delay.

The World Bank has stressed the need for research in the field of watershed rehabilitation. In view of the complexity of these research programmes, the socioeconomic and political implications and the need to pursue research efforts over a long period, the Bank considers that an international research programme should be envisaged and that the national centres for research on the subject should be strengthened.

e.g. "Extension campaigns" in Ghana. (Return)

Frans L. Schmidgall, FAO extension expert. Project UNDP/FAO TUN/77/007. Forestry development and erosion control. Tunis 1980. (Return)

For more details, please consult FAO document: "Agricultural Extension, a reference manual". Rome 1972, as well as the many other documents on the subjects, some of which are mentioned in Annex IV. (Return)

RDC, Holte, 1973. Report on the Fourth UN Seminar on "Training for Rural Development" P• 53 Denmark (all the participants were from Africa). (Return)

Panafrican Institute for Development (PAID), Douala, Buea, Ouagadougou. Rural Development College (RDC), Holte, Denmark. Institut Universitaire d'Etude du Développement, (MD), Geneva, Switzerland. (Return)

See "Guide to extension training" by D.J. Bradfield. Malawi. FAO. Rome. 1966. (Return)

The Forestry Division of FAO has just published a Training Manual for Extension Agents on Forestry for Local Community Development. (Return)

FAO document: RAFE 34. Learning from small farmers. FAO. Rome. 1978. P.48. (Return)

The Organization of Forestry Cooperatives, by M. Digby and T.E. Edwardson. The Plunkett Foundation for Cooperative Studies. Occasional paper No. 41. 1976. (Return)

They are revised periodically by the International Cooperative Alliance (ACI) at their congresses. (Return)

In Korea, 21 000 Village Forestry Associations are grouped under 41 Unions, in turn grouped into 9 Provincial Sections, all headed by a National Federation. (Return)

UNASYLVA Vol. 10. No. 2. 1956. (Return)

Dr. G. Fauquet. Le Secteur Coopératif. (1935). (Return)

Taken from the conclusions of the Centre for the development of agricultural credit for Africa. Dakar (Senegal) Sept.-Oct. 1965-Report No. AT 2154 FAO. Rome Rapporteur J.J. Bochet. FAO expert in Rural Institutions. (Return)

FAO Money and Medals Programme. Project proposal 3.5.77. "Guarantee-cum-Risk Fund". Bangladesh. (Return)

For more details, please consult the report of the mission conducted by J.J. Bochet, FAO Community Development and Agricultural Credit consultant Project Haiti HAI/77/005. 1979. (Return)

"The group training technique in agricultural extension work." FAO. Rome 1979 Pierre D. Sam and H.C. Ruck - diagram p.9. (Return)

World Bank - World Development Report. (Return)

The State of Food and Agriculture 1979. FAO. Rome. 1980. (Return)

The State of Food and Agriculture 1979. FAO. Rome. 1980. (Return)

Apart from its value in economic terms, the duration of the job is an important point. Jobs provided by programmes must ensure extra earnings to offset loss of income, but they must not incite the farmer to leave the land, as has happened in some cases. (Return)

FAO Soil Conservation Guide, No. 9 deals with encouragement and incentives used in rural development programmes in upland watershed areas. (Return)

The term "research" is used in the widest sense and includes collection and analysis of available data. (Return)

See document FAO/ROAP: Participation of the Poor in Rural Organizations. A consolidated report on studies in selected countries of Asia, the Near East and Africa. Rome 1979. By Bernard van Heck. Consultant. (Return)

Le mouvement coopératif africain: plus d'échecs que de réussites. René Dumont (Revue française d'études politiques africaines No. 59, 1970). (Return)

Taken from the conclusions of the Centre for the development of agricultural credit for Africa. Dakar (Senegal) Sept.-Oct. 1965-Report No. AT 2154 FAO. Rome Rapporteur J.J. Bochet. FAO expert in Rural Institutions. (Return)

World Bank. "Preliminary guidelines for designing watershed rehabilitation projects for Bank financing. by John S. Spears and Raymond D.H. Rowe. Paper prepared for the World Bank's Second Agri-Sector Symposium. 1981. (Return)