|

R. Adhikarya

R. Adhikarya is the Senior Training Officer at the Economic Development Institute of the World Bank in Washington DC. Prior to joining the World Bank he was Agricultural Extension, Education and Training Specialist at FAO.

Economic Development Institute

World Bank,

Washington, DC 20433, United States

e-mail: [email protected]

One of the important resolutions of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 was Agenda 21 which specified the need to increase environmental awareness and undertake specific public education programmes to foster sound and responsible environmental and natural resources management.

In recent years, an increasing number of decision-makers have become interested in mainstreaming environmental and natural resource management issues into agricultural policy formulation, programme planning and extension, education and training activities.

FAO has intensified efforts in promoting environmental education and training among its member countries. Through its Extension, Education and Communication Service (SDRE), FAO initiated field-level environmental education and training activities in close collaboration with strategic partner institutions in a number of Asian countries. This article presents the status of projects in eight institutions in six Asian countries (China, Bangladesh, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia) and the lessons learned, illustrated with specific examples.

In the environmental education training (EET) activities conducted by the eight participating institutions, the critical interplay between sustainable agricultural development, rapid population growth and environmental degradation was analysed. Taking into consideration the results of a training needs assessment, an analysis was undertaken to identify suitable points in agricultural training programmes for the integration of environmental content. To mainstream environmental education into agricultural extension and training programmes, an interagency and multisectoral policy advisory committee and a technical steering committee were established.

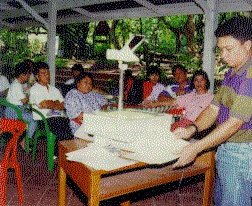

In order to communicate environmental issues to rural populations, six of the participating institutions are utilizing agricultural training centres which train extension or rural outreach workers to serve as the main channel for environmental education. The main target beneficiaries of these six institutions include: master trainers of training institutions; trainers of extension and outreach workers; fieldworkers of public extension services; and selected farmer/community leaders. Two other participating institutions have different target beneficiaries. In China, the Centre for Integrated Agricultural Development uses the Central Agricultural Managerial Official College to lobby high-level agricultural policy- and decision-makers by advocating the need for, and importance of, environment management policy and education issues. The International Institute of Rural Reconstruction (IIRR) in the Philippines is developing and conducting activities for rural outreach workers from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in the Philippines.

Environmental education activities in China

In undertaking EET activities, strategic alliances have been forged among relevant partner institutions, such as public-sector agricultural extension and training institutions, environment management agencies, training institutions, NGOs, community-based development agencies and multimedia development and training centres.

All participating institutions have conducted training needs assessments and used the results for designing curricula and developing environmental education training modules (EETMs). These modules have been pre-tested and presented for technical review and validation in at least two national workshops and three intercountry/ regional workshops.

Between 30 and 60 master trainers in all participating institutions have been trained in the use of the modules. Each master trainer is supposed to train 15 to 20 other trainers and these trainers, in turn, are expected to train at least two groups of 20 to 25 extension workers as part of their institution's regular training programme during the project period (two to three years). At least 932 environmental education trainers were trained as of December 1997, and more than 10 800 extension workers had also been trained in these six countries.

Modules have been reproduced for wide distribution to potential trainers and interested users in all participating institutions. In Indonesia, Bangladesh, China, the Philippines and Malaysia, the modules have been personally endorsed by the highest level policy-/decision-makers (e.g. the minister or director-general of agriculture, university rector or vice chancellor) and officially adopted as required modules for in-service training of agricultural extension workers. In Indonesia, the modules have been adapted and utilized by several NGOs and a local government institution (East Java Province) and the Agency for Agricultural Education and Training/Ministry of Agriculture has used its own resources to develop an advanced-level module and to train additional trainers and extension workers. In Malaysia, Bangladesh and China, the training of extension workers has been carried out without FAO/SDRE support. In the Philippines, additional funding from other donor agencies has been obtained to share the cost of their activities. In Thailand, the Continuing Education Center (CEC) of the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) is utilizing selected parts of the eight modules for its own environmental training course.

Three regional workshops have been convened. The 1994 Kuala Lumpur workshop focused on strategic planning and participatory development of EET processes and methodologies. The 1995 Bali workshop reviewed the progress of module development and testing, discussed possible improvements and considered plans for training master trainers. The 1996 Beijing workshop discussed the results of the use of modules, considered plans for the training of extension workers and proposed improved strategies for the institutionalization of EET and its expansion to different environmental subjects and advanced-level topics. During these workshops, new people were invited to join an environmental education network, which included participants and/or resource persons from Nepal, Ethiopia, Malawi, Kenya and Egypt.

Environmental education activities in the Philippines

One of the recommendations of the Beijing Workshop and also the World Bank's Global Knowledge '97 Conference held in Toronto, Canada, was the creation of an on-line knowledge database and an electronic network to facilitate an interchange of ideas among members of the rapidly expanding network. As an interim measure, network members can use the World Bank's post-conference web site at: http://www.worldbank.org/ html/edi/toronto/post/index.htm. A more permanent web site is being planned.

A book about this EET programme entitled Participatory environment education and training for sustainable agriculture: best practices in institutional partnership, peer learning and networking will be published by FAO. This book is being prepared by T. Wentling, R. Adhikarya and C.H. Teoh (as editors) with contributions from task managers of the eight participating institutions and selected network members.

The following are best practices learned from the results and experiences from environmental education and training activities in the six Asian countries

Build strategic alliances with appropriate partner institutions:

| Partnerships with strategic training institutions: a key to sustainability |

Possibilities for training agricultural extension workers on environmental education in Indonesia in a systematic and insitutionalized manner were studied and explored. In 1992, FAO/SDRE collaborated with the Indonesian Agency for Agricultural Education and Training (AAET) which provides in-service training to all the 33 000 Indonesian extension workers, in developing institutional and staff capabilities in designing and utilizing well-planned and pre-tested environmental education training curricula, modules and learning materials. With initial funding of US$10 000 and some technical support from FAO/SDRE, AAET was responsible for designing a participatory process that involved its master trainers, selected extension workers, environmental specialists, local leaders and other relevant stakeholders. Their task during the first phase was to develop, test and produce an EET module of between 15 and 17 instructional hours for use by its trainers for training extension workers and which would be incorporated into the in-service training curriculum. The second phase included activities such as: training of master trainers in production of prototype materials. FAO contributed an average of US$10 000 to $12 500 for each phase. However, expenditures for scaling up the activities, such as the cost of reproducing materials and training larger numbers of field extension workers, have now been covered by AAET through their own regular budget. As of December 1997, at least 5 300 extension workers had been trained using the two training modules developed by the project. |

Strategic positioning of environment education messages for rural populations:

Communicating environment issues to rural populations:

| Participatory planning: helping and learning from others |

Based on the encouraging results and positive experiences of the Agency for Agricultural Education and Training's EET activities in Indonesia, a participatory environmental education programme was designed and planned for interested institutions in the Asia region. The Agency for Agricultural Education and Training's basic EET module was translated into English by two staff members of the Agricultural University of Malaysia who had also participated in the pre-testing of the EET module by the agency's staff in Indonesia. The Indonesian EET module was then used as a prototype or model for adaptation, testing and improvement by other training institutions participating in the project. During the annual "peer review" meetings/workshops, project network members shared their experiences with each other and collaborated in improving the training modules. |

Use a participatory approach to encourage local ownership:

| Learning from below: needs-based, demand-driven, diagnostic planning |

The integration of EET through agricultural extension programmes started as early as 1987 in Indonesia through an FAO technical cooperation project. The request, from the State Minister's Office of Population and Environment in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture, was to design and test a methodology for involving field agricultural extension workers in assessing and reporting on environmental problems in two provinces (Grobogan district, Central Java and Central Lombok district, Lombok). While the project was successful in developing a methodology for environmental monitoring and designing needs-based , problem-solving activities with the active participation of agricultural extension workers, concerned farm families and local leaders, it did not include an institution-building and/or staff capacity-development or training component. Extension workers served as effective facilitators in encouraging a two-way flow of information and opening up communication channels between relevant government officials, local leaders and concerned farm families. However, the activities were undertaken on an ad hoc and sporadic basis and were not sustainable. From this experience, it was concluded that the expansion of project activities to other areas would require: 1) wider involvement of agricultural extension workers in an institutionalized manner; 2) the integration of environmental education into relevant, on-going agricultural extension programmes; and 3) systematic and high-quality training of extension workers on relevant environmental education issues, strategies and methods by authorized agricultural training institution(s). |

"Franchising" and "wholesaling" of EET:

| Develop and use participatory processes and guidelines |

During the 1994 Planning Workshop in Kuala Lumpur, the participants developed generic guidelines for EET which have been used to plan and implement EET activities. The guidelines also provided step-by-step standard operational procedures, including suggestions for the development of training modules. Such guidelines are continuously revised and improved on the basis of the experiences of participating training institutions and comments from members of the EET network. |

Quality assurance and standards:

Advocating multidisciplinary partnerships:

Facilitating institutional and professional networking activities:

| Development of knowledge partnership networks |

FAO/SDRE sponsored a workshop for EET in Kuala Lumpuer, Malaysia, in June 1994 which was organized by the Agricultural Universty of Malaysia. Twenty-three participants from ten countries (China, Bangladesh, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, the United republic of Tanzania, the United States, Australia and Italy) attended the workshop, representing public-sector training and extension agencies, NGOs, universities, international organizations and multidisciplinary specializations ranging from environmental science and management, agriculture, economics, public policy, education, training, communication, rural extension, etc. Workshop participants discussed and agreed on a conceptual framework, strategy, operational processes and implementation procedures for EET programmes. The guidelines included participatory mechanisms to ensure the relevance of programes and to facilitate knowledge exchanges and experience-sharing among institutions and planners at the country, regional or global level. Several workshop participants who are not undertaking EET activities agreed to join a panel of resource persons who could provide advisory, review, monitoring and problem-solving services. This network of resource persons has proved critical in providing participatory consultations, peer learning and reviews and high-quality assurance and standards. |

Preparing documentation:

Completing the "last-mile" tasks:

|  |