M.J. Creek*

At least 100 visitors a month are shown around the feedlot of the Kenya Beef Industry Development Project. One of the commonest questions asked is: “What do you do with all the fat beef? Surely nobody wants to buy fat these days?” A similar question was asked by the appraisal team which reviewed the initial project request from the Kenya Government to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and a variation of the theme comes from livestock development experts: “Why produce fat expensively in a feedlot when grass can produce cheap protein on the range?”

The answer to all these people is that an adequate fat cover on the carcass is essential for the successful marketing of beef. To put it bluntly, cattle in Africa are so undernourished that they have too much lean in relation to the fat they carry. Early in 1971 the intake of cattle at the Kenya Meat Commission abattoir was so lean that there was not even enough fat to meet the minimum requirements of the canning line (i.e., 9 percent) and production had to be stopped. While it is true that modern markets like lean beef, there is still a great deal more fat in such lean beef than is to be found in the average beef animal in Africa. Moreover, although the average East African consumes barely 2 000 calories per day, he greatly prizes fat in the carcass and wants to find it at a fairly high level.

It is well known that there are two factors which affect the amount of fat in the carcass: the level of nutrition and the age of the animal. At a low level of nutrition an animal grows only bone and muscle, but after maturity, when growth stops, fat may be laid down. When fat is laid down at this stage of maturity it tends to be an energy store, and it grows in large blobs over the back and in the pelvic channel. This fat distribution is acceptable to the local market, but for the export market it must be trimmed off. With a sufficiently high level of nutrition, however, a young animal can be induced to lay down fat as well as to grow. When this happens the distribution of fat is much more even: it lies as a thin envelope over the entire carcass — which is just what the export market requires.

It is often argued that African beef has its best chance in export sales as manufacturing beef, for which there is a large and rapidly growing market. The problem is that the costs of manufacture and packaging are such that the return to the producer per kilogramme of cold dressed weight is some 25 percent less than the price at which the meat can be sold on the higher quality market.

Thus the whole rationale of introducing a feedlot system into Africa is not as a method of producing beef from crops. Instead it is a method of preparing the live animal produced from the range so that, at slaughter, its carcass has the correct specifications to meet market requirements. The production of beef then becomes a three-stage process of calf production, growth and finishing. Finishing in a feedlot instead of on the range allows for specialization in calf production and in growth on the range, which in itself has important consequences. The ease with which a rancher can finish cattle on the range depends upon the type of his range, the quality of its forage and the stocking rate he uses. While there are some ranches in Kenya where cattle can be finished in any one of eight months of the year, in most areas the quality of the range is such that cattle can only be finished for three or four months of the year — or only after favourable rains. If cattle fail to reach an adequate finish during this period, then they are kept for a further year, or marketed in an unfinished condition.

* undp Special Fund Project, Nakuru, Kenya.

Feedlot finishing of pastoral cattle

The trials carried out by the Beef Industry Development Project have shown that all of the cattle breeds and crossbreds which are available in Kenya will respond well to feedlot finishing. However, since Boran, the indigenous Zebu breed, is the commonest, its response to feeding is highly important. So far, the experience which the project has had with Boran cattle has shown them to be ideally suited to feedlot finishing, contrary to almost everyone's expectations.

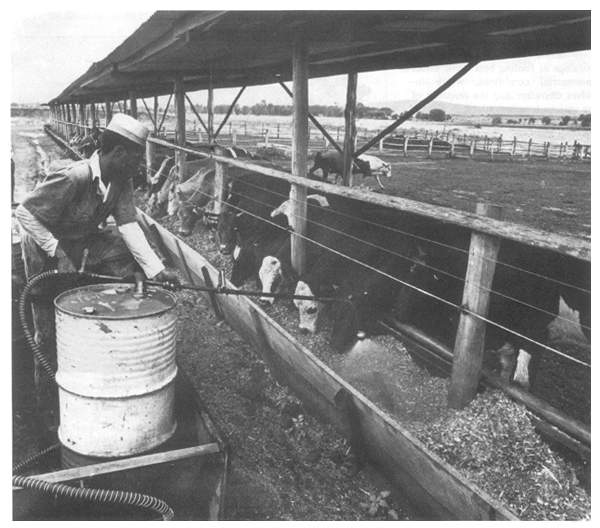

Figure 1. Molasses being sprayed onto the teed concentrate at the feedlot

Because of disease control limitations, cattle are brought into the feedlots only from the North Eastern Province of Kenya. Such cattle are purchased in outlying areas of the country by a government department, tested for bovine pleuropneumonia and vaccinated against footand-mouth disease. After a period of quarantine they are moved to ranches in the disease-free areas where they are grown out for a period of 6 to 12 months. This period on the ranches not only helps in controlling disease, but also offers an opportunity for cheap growth, thus capitalizing upon the excellent rangeland in Kenya.

When the animals are transferred to the feedlot the accent changes from growth to finishing. The steers gain in weight at a rate of about one kilogram per day, although this growth alone would not pay for the expense of confining them in a feedlot; but in a remarkably short time the animals also begin to finish by laying down a layer of fat. As explained earlier, this has the effect of increasing the market value of the meat. It is this increase in grade, coupled with the live-weight gain of the animals, which makes the feedlot an economic proposition. Using unimproved pastoral cattle it is possible profitably to increase the yield of edible carcass from one animal by between 30 and 50 percent during 10 weeks in the feedlot. The implications of this statement are nothing less than revolutionary for beef production prospects in Kenya.

Results obtained in the feedlot

The main concern of the project is to define the input/output relationships of feeding beef cattle under commercial conditions, which involves characterizing the response of the various breeds available in Kenya. The breeds have been arbitrarily classified as follows:

Unimproved (or North Eastern Province) Boran

Improved Boran (from commercial ranches)

Large crossbreds (e.g., Friesians, Devon or Charolais × Boran) and

Small crossbreds (e.g., Hereford or Angus × Boran).

Trials are being held to characterize the response of these cattle to different rations and feeding periods, and so determine what type of ration and for how long each class of steer should be fed.

The broad design of the trials is as follows:

| 4 BREEDS | - | as mentioned above |

| × | ||

| 2 RATIONS | - | high energy/high roughage |

| × | ||

| 2 PERIODS | - | 10 weeks/16 weeks |

Thus 50 head of each of the four breeds are fed on a high energy ration and 50 head on a high roughage ration. After 10 weeks, half of each group is slaughtered and the remaining half continues on feed for a further 6 weeks.

The first of the trials was completed in August 1971, and Friesian × Boran and Hereford or Red Poll × Boran were taken as representative of a large and a small crossbred, respectively (Table 1). The following rations were used:

| High energy | - | 67 percent concentrate/33 percent roughage |

| High roughage | - | 33 percent concentrate/67 percent roughage |

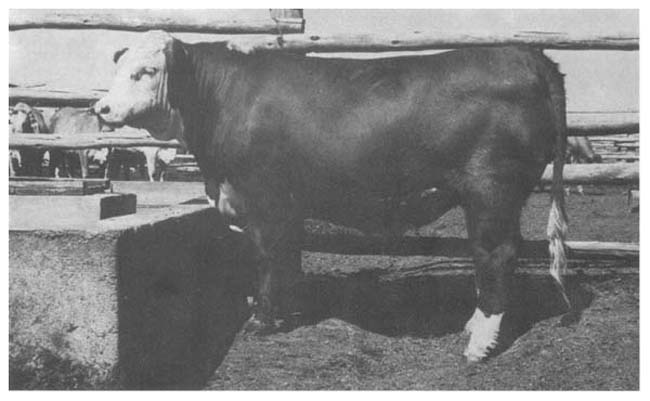

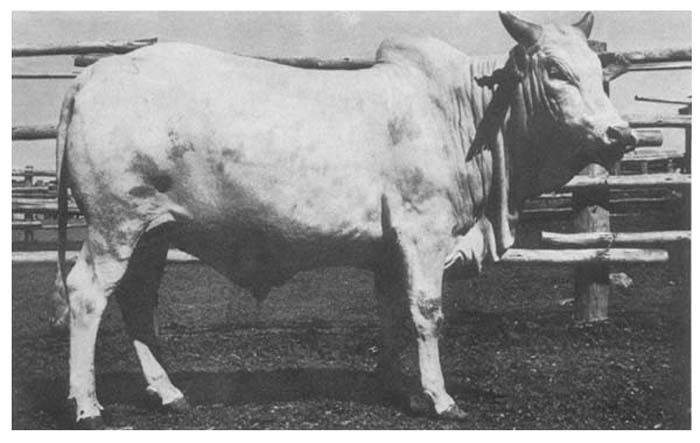

Figure 2. Typical example of the North Eastern Province Boran cattle when entering the feedlot

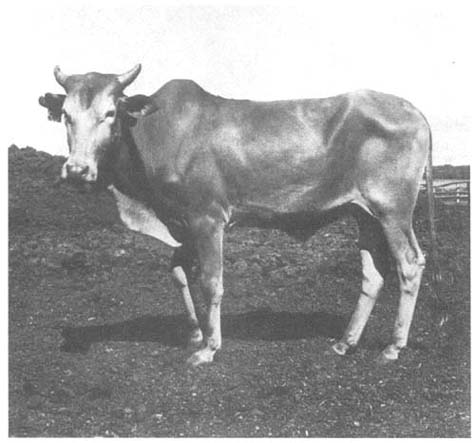

Figure 3. North Eastern Province Boran steer after 70 days' feeding

Table 1. Summary results of first breed characterization trial

| Breed | North Eastern Province Boran | Improved Boran | Friesian cross | Hereford cross | North Eastern Province Boran | Improved Boran | Friesian cross | Hereford cross |

| High energy | 10 weeks | 16 weeks | ||||||

| Average daily gain (grams)1 | 1 023 | 1 303 | 1 384 | 1 378 | 993 | 1 260 | 1 388 | 1 384 |

| Kg feed/kg gain2 | 8.1 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 8.7 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 7.2 |

| Grade score3 | 4.54 | 4.57 | 4.26 | 4.67 | 4.38 | 4.83 | 4.65 | 4.96 |

| Dressing percentage4 | 51.2 | 51.1 | 50.7 | 49.2 | 52.9 | 52.4 | 52.7 | 52.1 |

| Feed cost/kg gain (U.S. cents/kg)5 | 29.4 | 25.5 | 24.8 | 24.6 | 34.2 | 27.7 | 25.8 | 30.2 |

| High roughage | 10 weeks | 16 weeks | ||||||

| Average daily gain (grams) | 815 | 890 | 868 | 795 | 883 | 1 098 | 1 060 | 1 047 |

| Kg feed/kg gain | 10.1 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 10.5 | 9.5 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 9.1 |

| Grade scores | 4.60 | 4.64 | 3.84 | 4.56 | 4.24 | 4.68 | 4.38 | 4.67 |

| Dressing percentage | 50.0 | 50.3 | 48.5 | 49.2 | 51.7 | 52.0 | 50.9 | 51.3 |

| Feed cost/kg gain (U.S. cents/kg) | 31.7 | 29.4 | 30.7 | 33.9 | 30.7 | 26.2 | 26.2 | 29.8 |

1 Based on carcass weight and a standard 51 percent dressing percentage.

2 Feed expressed on a dry matter basis.

3 6 = Prime, 5 = Choice, 4 = FAQ, etc. (Prime is the highest grade).

4 Based on unfed farm weights.

5 Daily added value minus daily feed and nonfeed costs (including interest and mortality).

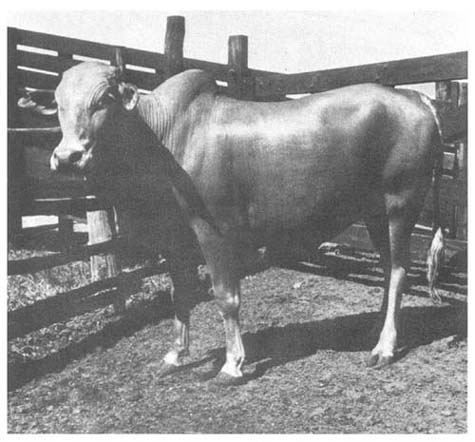

Figure 4. Improved Boran steer after 70 days' feeding

Both rations were made from standard ingredients and their composisition is shown in Table 2.

What do these results mean to the beef producer in Kenya?

In the immediate future the answer is “very little.” At present the results can only be used to show the potential for cattle feeding and to interest an investor in setting up feeding facilities. The real benefits will only come when a feeding sector is established in the beef industry with a capacity to feed at least 50 000 head a year. When this happens new opportunities will present themselves to producers. Movement of cattle will become more commonplace, and the producer will have a better opportunity to sell immature cattle at a fair price. Equally, investment in feedlots will underpin investments in abattoir construction and live animal marketing facilities. Both of these sectors can only operate effectively when a sufficient volume of business can be guaranteed to carry their overhead costs.

Table 2. Percent of ration composition (on a 100 percent dry matter basis)

| High energy | High roughage | |

| Percent | ||

| Maize grain | 52.8 | 20.6 |

| Maize silage | 33.4 | 66.8 |

| 4 percent urea molasses | 11.1 | 9.9 |

| Cottonseed cake | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Cost (in U.S. cents per kg dry matter) | 3.1 | 3.7 |

Perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of the results so far is the performance of the various breeds and crosses. The indigenous Boran appears ideally suited to finishing because its turnover is rapid and the total quantity of maize needed to finish an animal is relatively small. On the other hand, the crossbred does give a better carcass, and in times of grain surplus — when feed costs are cheap — they would become comparatively more attractive to finish than the Boran. It is predictable that the crossbred will become more important in the future; but for today the cattle which are present in the greatest numbers, and which are fully adapted to the conditions of the country, form the best basis for starting a cattle feeding industry.

If one takes a wider view, there are over 100 million head of cattle in Africa south of the Sahara. They form a tremendous natural resource which is intimately linked with the way of life of the people who own them. Perhaps a desirable result of the Kenya project will be to make people look at native cattle in a new light, and appreciate the inherent possibilities that exist for development.

Figure 5. Hereford × Boran steer after 70 days' feeding