0212-B1

XII WORLD FORESTRY CONGRESS

Edward Mufandaedza 1

In Zimbabwe, there are two systems of forest and woodland management. One is the conventional centralised, protectionist and forest centred system ,initiated, implemented and imposed by the state through the forestry department. The other is the traditional or customary approach initiated and implemented by local communities and individuals. The former uses the national forest legislation and policy to manage and regulate use of state forest reserves, while the later uses tradition, cultural beliefs, taboos and values to manage and use local trees and woodlands.

The conventional system of forest management by the state forestry department is geared towards production for commercial purposes, protection and conservation. This type of management generally follows strict scientific principles involving the application of appropriate forest research, silvicultural treatments, inventories, forest protection measures and the regulation of exploitation of the forest. In most countries the objects of managing indigenous forests vary from pure forest centred objects to those that called for multiple uses. In Zimbabwe the objectives of management for the indigenous state forest reserves were postulated in 1961 as:

Despite the noble recognition that the forests should not be managed for timber alone, management for commercial timber production was seen as the primary objective, alongside protection of watersheds.

Indigenous state forest reserves are managed purely for conservation, commercial production and utilisation, with all the benefits accruing to the state. Public or local use of these protected forests is not allowed except with the authority of the Government Forestry Agent. In almost all the cases, families who had lived in these forest areas were evicted at the time of forest gazetation and without any compensation for loss of their ancestral land. During the land Apportionment era of 1930, families who had been evicted from areas gazetted as commercial farming areas settled in some of the present forest reserves before these were gazetted. The same families found themselves at the mercy of the Govt Forest Dept. at the time of gazetting. Thus one can appreciate the origin of conflict between the commercial farmers, the forestry dept and these communities. It is this kind of conflict of forced alienation from ancestral lands that has resulted in persistent land claims particularly after Zimbabwe's independence in 1980. This in turn has resulted in growing pressure from the ex-forest dwellers and other landless local communities who aspire to settle or gain uncontrolled access to forest areas and their products. Uncontrolled settlements, agricultural practices and access into the protected forests threaten the existence and sustainability of the forests.

When we consider forest management approaches by rural communities it would be realised that the approaches were geared to ensure the forests provided basic goods and services for livelihood sustenance for all classes of the community. Subsistence for the rural folks is heavily dependent on the goods and services from the forests, e.g., fruit, poles, thatch grass, fuel wood, medicines, fodder, living fences, windbreaks, etc.

Given the above background, secondary forests are under threats from fires, logging operations, poaching, settlement and agricultural activities of various forms.

Zimbabwe is a land locked country covering about 39 million hectares. Mean annual rainfall varies from 400 mm in the low-lying Zambezi Valley to 1,500 mm in the Eastern Highlands. The soils in Zimbabwe vary from less fertile sandy granite-derived soils, which constitute 70% of the soils, to fertile clay igneous intrusion soils.

Exotic forest plantations based primarily on Pinus and Eucalyptus species cover about 155,000 ha (0.4% of the country) and are located mainly in the high altitude, high rainfall Eastern Highlands of Zimbabwe. Natural Forests and woodlands cover about 25.8 million ha (65.5% of the total land area). About 40% of the indigenous woodlands are situated in communal areas where they are traditionally exploited for fuelwood and construction poles.

There is a decline in woodlands mainly due to clearing for agriculture, and partly due to the harvesting fuelwood and construction poles, infrastructure development and overstocking of domestic animals. Rapid population growth puts a strain on natural resources as well. Approximately 100,000 ha of forest are cleared annually.

Forests (both natural and plantations) in Zimbabwe cover about 66% of the total land area of the country (39 million ha). About 40% of the indigenous woodlands are situated in communal areas where they are traditionally exploited for agriculture land, and partly due to harvesting of fuelwood and construction poles, infrastructure development and overstocking of domestic animals. Approximately 100,000 ha are cleared annually (Gondo and Mkwanda, 1991). Most forest cover is found in the gazetted state forests, National parks, commercial farming areas and the eastern highlands of the country. The current assessment does not give estimates of woody biomass in natural woodlands except where commercial timber extraction is taking place. Exotic plantations cover about 156,000 ha (0.4%) of the country) of which 90% is located in the high altitude, high rainfall eastern highlands.

| Table 1. Estimates of the extent of each land use system in Zimbabwe |

Land use |

Area (000 ha) |

% Of total area |

Rain Forest |

12 |

0,03 |

Plantation |

156 |

0,40 |

Indigenous woodlands |

25 772 |

66,00 |

Grasslands |

1894 |

5,00 |

Cultivated land |

10 783 |

27,00 |

Settlements |

139 |

0,36 |

Other (waters, rocky outcrops) |

257 500 |

0,70 |

Total |

39 090 |

100,00 |

| Source: Forestry Commission (1996) |

The indigenous woodlands and bush lands can be divided into 5 types (Bradley and McNamara,1993). There are basically four vegetation types in Zimbabwe; Baikiaea, Mopane, Miombo and Combretum, Terminalia and Acacia woodlands.

The distribution of the major vegetation types are shown in table 2 below.

| Table 2. Distribution of the major woodland types by land tenure category in Zimbabwe (1,000 ha) |

Vegetation type |

Communal |

Private |

State |

Total |

Miombo |

671 |

158 |

1037 |

35 666 |

Mopane |

22 264 |

3520 |

2395 |

8 180 |

Teak |

16 |

206 |

981 |

1 365 |

Others |

237 |

1501 |

1129 |

2 868 |

Total area |

3 333 |

7 085 |

5 542 |

15 960 |

| Source: Coopers and lybrand (1985) |

The main types of secondary forests found in Zimbabwe :

By definition, these are the" forests regenerating largely through natural processes after significant reduction in the original forest canopy through tree extraction at a single point in time or over an extended period, and displaying a major change in forest structure and or canopy species composition from that of potential primary or natural forests on similar site conditions in the area given a long time without significant disturbance."

A survey was done on the 10 th of September this year to find out the evidence of a secondary forest in Gwaai forest in the Lupane District about 140km away from the city of Bulawayo. Height and diameter measurements were taken on logged and un-logged sites. The area was last logged in 1980, that is about 22 years ago. The graphs below show the diameter and height distribution of the logged and un-logged areas.

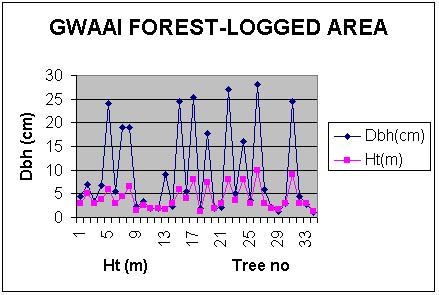

Figure 1. Graph showing the diameter (cm) and height (m) distribution in a logged area of Gwaai forest.

The graph above shows that big trees ( >31cm) have been harvested. This is clear evidence of selective harvesting. Most of the growth is the regeneration or secondary forest of the past 20 years. But this scenario needs to be compared to an adjacent area which did not undergo logging operation during the same period (see fig 2) below.

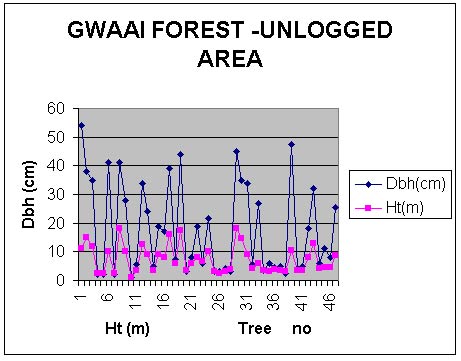

Fig 2 Graph showing the diameter (cm) and height (m) distribution in un-logged area of Gwaai forest.

Figure 2 shows that most diameters are above the 31cm threshold indicating that the un- logged area is predominantly composed of primary forest. Regeneration is evident from the shade tolerant species with diameter as low as 1.2 cm at breast height.

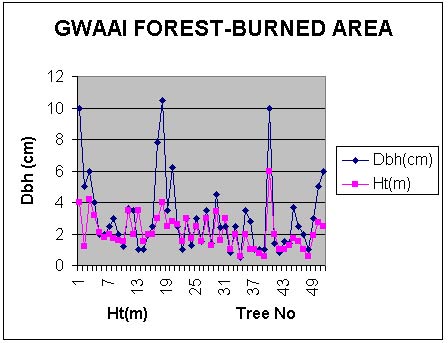

Fire influences the environment directly and indirectly. Fire may directly change soil and atmospheric temperatures during a fire, consume organic matter and release nutrients. Fire indirectly affects the environment by consuming plants and litter thereby creating space for establishment of plants and modifying the post-fire microclimate and activities of the soil biota (Frost and Robertson, 1987). Some measurements were taken in the Gwaai forest to see the effect of fire on the vegetation structure and composition in relation to the regeneration of the secondary forest (fig 3 below). As can be seen from fig 3 below, the maximum diameter is just above 10 cm and the minimum diameter is 0.5 cm with a mean diameter of 3 cm. The heights measured ranged between 0.6 and 4 m with a mean of 2.1m. The measured plot is heavily stressed and what is clear from the field is that Bauhinia macrantha secondary regeneration is taking over from the former Baikiaea plurijuga (Teak) forest. Regular late fire favours species such as Burkea africana and Terminalia sericea, but not Baikiaea plurijuga.

Shrubs such as Bauhinia macrantha and Commiphora mossambicensis increase under fire regimes. This observation was confirmed by (Calvert,1986). Fire reduces the mean heights and increases coppice stems of desirable regeneration. Baikiaea appears affected more than Guibourtia by fire. (This conflicts with Forest Research Centre conclusions of Calvert of 1969). The diameter distribution of a burned area needs to be compared to the diameter measurements in un-burnt area (see fig 4).

Fig.3. Diameter (cm) and height (m) distribution in a burned area of Gwaai forest.

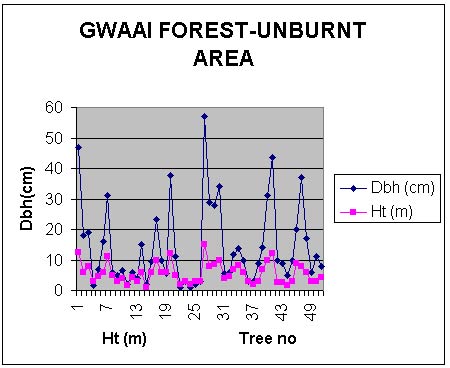

In un-burnt area the distribution of the diameters and heights is sought of normal whereby small, diameters in between and large are present in the forest. This is evidence of a growing forest (see figure 4 below. The distribution of diameter measurements range between 1 cm and 57 cm with a mean diameter of 14.2 cm. Height measurements range between 1m and 12.5 m with a mean height of 5.6 m.

It is clear from the graph below that most diameters have grown past the take off diameter of 31 cm. Evidence of regeneration is also clear from the smaller diameter measurements encountered during the inventory. Bauhinia macrantha persists very well under fire suppression and it is clear that in areas of repeated fire frequency Bauhinia encroachment is abundant.

Fig 4 . Distribution of diameter (cm) and height (m) in un-burnt area of Gwaai forest.

Post abandonment secondary forests: "forests which regenerate largely through a natural process after abandonment of alternative land uses such as agriculture or pasture growing for cattle". There is a clear evidence of the abandonment secondary forest in Gwaai forest in Lupane District and Gwampa forest in Nkayi District. This is true in post resettlement areas. The tree diameter ranges in these areas lie between 1 cm and 13.8 cm. Height ranges lie between 0.5 m and 14 m. This is so because the areas had been cleared for agriculture before. But because of poor soil conditions and erratic rainfall the settlers were forced to move to alluvial areas along the Gwaai River. Secondly, lack of security of tenure arrangements forced some settlers to move to secure areas. This is so because these areas are government areas held by the Forestry Commission, the state forest authority.

Natural forests if not grossly abused could be managed by natural regeneration system of secondary forests, that is, managing the natural forest to replace itself especially after a disturbance.

What is advocated here is an appropriate application of the classical selection system, which Smith (1992) defines as " any silvicultural program aimed at the creation or maintenance of uneven-aged stands." An uneven-aged stand is one in which the trees are of varying age and can be put into a continuum of discrete diameter classes.

Each year a tree puts on an increment of volume growth, and these growth increments can be developed into a curve showing an increment for a given age and diameter. Sigmoid curves for timber species are developed from enumeration studies on permanent sample plots over long periods. In developing a selection system it is necessary to know the diameter distribution by area for trees involved. The system, in its simplest terms, allows for the replacement of volume removed by the growth increment, or "in-growth" (Smith, 1962). Secondary trees from younger classes "move up" (are recruited) into larger classes to replace the trees cut in those classes.

Normally, a cutting cycle of x years is allowed, with the assumption that in the period between fellings the forest will have regained the lost volume. Forty years is the cutting cycle used in both Zimbabwe and Botswana.

Development of a managed selection system will require research and dedicated and trained personnel. Its effects will not be easily seen, but any increment added to or saved in the natural forest is a tangible asset for the future. Volume adds up, and the cumulative effect can be substantial.

While complete protection from fire is obviously desirable for maximum production of secondary forest, Farquhar's results in 1969 suggest that a burn in May is not as detrimental to species numbers and structure as has been thought.

However, before prescribed fire can be used with any confidence as a protection measure in the management of Baikiaea and other natural woodlands, further careful research is essential to determine in particular, the periods of minimum and maximum susceptibility to fire and the period of dormancy within a season wherein fire susceptibility is minimal.

Prescribed fire must be applied flexibly on the basis of environmental conditions allied to the physiological state of the plant community concerned, not on a rigid calendar prescription. This is so because to a large extent, fire is a critical factor in the regeneration and development of secondary forests in any ecosystem.

Chihambakwe, M.1987. Multiple use management of indigenous forests in Zimbabwe: experiences and options. In: Report of the workshop on the Management and Development of Indigenous Forests in the SADCC Region,Victoria Falls,Zimbabwe, October 19-25,1987.pp.177-185.

Bradley, P.N and K. McNamara (eds.), 1993. Living with Trees: Policies for Forestry Management in Zimbabwe. World Bank Technical Paper No. 210.

Gondo, P.C.and Mkwanda,R.(1991).The assessment and monitoring of forest resources and forest degradation in Zimbabwe. Proceedings of regional workshop on methodology for deforestation and forest degradation assessment.1991,Nairobi,Kenya.

Calvert,G.M.1986. Fire effects in Baikiaea woodland, Gwaai forest. In: The Zambezi Teak Forests, 1986.

Frost, P.G.H. and Robertson, F. 1987. The ecological effects of fire in savannah. In: B.H. Walker (ed.). Determinants of tropical savannahs. IRL Press, Oxford, pp 3-140.

Boughey, A.S. 1963. Interaction between animals, vegetation and fire in S.Rhodesia.Ohio Journal of Science 63 (5): 193-209.

Boughey,A.S. 1964. Deciduous thicket communities in N.Rhodesia. Adansonia 4 (2): 239-261.

Fanshawe, D. B. 1961. Baikiaea plurijuga. Manuscript. Division of Forest Research,Kitwe.Zambia.

Fanshawe, D. B. 1971. The vegetation of Zambia. Forest Research Bulletin No.7. Government Printers, Lusaka.

Murphree, M.W.1991. Communities as Institutions for Resource Management. CASS Occasional Paper NRM. Centre for Applied Social Studies, University of Zimbabwe.

Mandondo, A. in press. Trees and spaces as emotion and norm laden components of the local environment in Nyamaropa Communal Land, Nyanga District, Zimbabwe Agriculture and Human values.

King, L.A. 1994. Inter-organizational Dynamics in natural Resources Management: A study of CAMPFIRE Implementation in Zimbabwe. Cass Occasional Paper NRM, Centre for Applied Social Sciences, University of Zimbabwe.

1 Forestry Commission

Box 467 Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

Tel 263 9 61495/6

Fax 263 9 71133

Cell 011 862 169

E-Mail: [email protected]