0213-B2

Sudeepto Bhattacharya 1, Rucha Ghate 1, Shree Bhagwan 1,2

The present context of wilderness and biodiversity conservation practice and policies in India need to be of an inclusive type, thereby promoting an active participation of the primary stakeholders in particular and the local population inhabiting the areas inside and around the PAs in general. The issue is to strike a partnership in the process of wildlife conservation, so as to benefit both, the biodiversity of the region as protected in the PA as well as of the primary stakeholders, who depend for their subsistence on the PA. Such an interactive approach is theorized in the paper based on the fieldwork undertaken in a typical Tiger Reserve in the Central Indian Plateau. Through construction of Utility Possibility Frontier for conservation versus development as well as the production curve, and by obtaining the integral curves of Social Welfare Function, an optimal point is arrived at as an intersection of the UPF, the SWF and the productivity curve, which is estimated through the production function of the competing communities. By attributing values to the various parameters above, the relative position of the curves could be obtained. Based on the graphical position, suggestion as regard to the management priority and policy implementation could be made to the concerned agencies, so as to optimize the benefits to the conservation as well as livelihood objectives.

The setting aside and earmarking of wilderness area as PA 3 in India has not really helped the primary stakeholders, in particular, the local populace to perceive the cause and objective(s) of specie-specific conservation programmes. In fact such exclusions have

(i) has resulted in direct transfer of resources from the poor to the rich, and 1

(ii) has not adequately addressed the key environmental problems like those relating to fuel, fodder, water etc. that directly impinge upon the lives of the local populace surrounding the PAs. ( Guha 1989 ). sharply posited the interest of the protected species (Panthera tigris Tigris for our study) against those of the communities living in and around the PAs (in India, around 3 million people reside inside the reserves). This kind of an exclusive "deep ecological" management practice, totally keeping away the marginal producers and subsistent population, is deeply rooted in the US conservation history and experience. Consciously to imitate this or otherwise, this practice has spread most extensively in India, regardless of the existing socio-cultural context.

As a consequence of (i) and (ii) above, the protected specie, tiger, has hardly gained a constituency from the local communities to enable them to see the cause and imperatives for its conservation and long-term survival (Seidensticker et al. 1999). Since such a method of conservation treats the tiger and the local populace in and around the reserves as if with conflicting interests, the consequence has inevitably led to the `conservation' versus `development' debate (Guha 1989a; Guha and Gadgil 1996; Fernandes 1996).

One of the major weaknesses of the PA concept, identified at the IV World Congress held at Caracas, is the inadequate recognition of the needs and interests of the local people upon whose support the existence and long-term survival of the PAs will depend (Bishop et al. 1995). In the present day context, the PAs need to be integrated into wider state policies and networks as well as the management needs to be adequately sensitive to the needs of the local populace. Discovering and creating stakes and identifying the stake holders in conservation of biodiversity should be one of the most vital focal area for bringing out the actual and desired effectiveness of the PA concept (Pathak and Kothari 1998).A proper designing coupled with an efficient management of the PAs can offer sustainable benefits to the local community playing a central role in the socio-economic development of rural environments ( Balakrishnan and Ndhlovu 1992 ).

Conserving tiger and its habitat means conserving the biodiversity of the area in general, since the tiger is an umbrella specie. As has been spelled out in Tiger 2000 at London, the issue is to secure a future for the tiger from this point of view. Since humans are a part of any ecological system, securing a long-term future for the tigers in the wild essentially will require a proper consideration of the needs of the people and of the tiger simultaneously in any module of conservation to address the objectives holistically.

The economic options of sharing the benefits between the tiger and the local communities, derived from conserving the tiger habitat landscapes without antagonizing either, needs to be explored and analyzed. The impossibility of separating the interests of the tiger from those of the humans and vise versa needs to be reinforced as a policy tool (Thapar 2001).

Nature conservation practice has been evolving dynamically worldwide over the years, benefiting from the field study inputs. One of the most significant evolutions has been the shift of emphasis from protection of the species to the protection of their habitats (Bishop et al.1995). Such a change in the philosophy of conservation has made it essential to reassess the role of PAs as state instruments for conservation in Indian context. PA policy must now be developed in a multidimensional, multidisciplinary context, offering a space for the sustainable benefits to the stakeholders in the PAs.

Before we begin our exercise, we feel it an imperative to reflect on the categorization of the various stakeholders as primary, secondary etc. Such categories are more often created based on certain value parameters like existing rights to land or natural resources, continuity of relationship with the PA, historical and cultural ties with the resources at stake, to mention a few. However, we maintain that in spite of essential similarities we must recognize the conflicts and non-parallel interaction even among actors at the same category level. One population, A, may use the forest resources for economic advancement while another, B, may use the same for livelihood sustenance. Although both A and B will be categorized as primary stakeholder, it is obvious that the motives of land and resource use of the two will be quite different. It is thus felt necessary to distinguish between the primary stakeholders on some finer yardstick, since the interest factors of the above two groups are also bound to be distinct over a sizeable chart. This automatically will influence their nature of participation in conservation of biodiversity of the area.

In spite of the existent intra-class disparity mentioned above, the essential similarity and congruencies in the modes of production and consumption place the local populace generically in a single bracket, thereby identifying them as one of the key social actors with the following types of attributes:

Consequent upon these, the local population is recognized as primary stakeholders. For the locals, the stake may usually originate from one, many or all of the following factors: geographical mandate, bequest value, historical association, dependence for livelihood and economic interests to mention a few.

In the perspective of the above, it is felt that securing partnerships and linkages with the local populace based on sustainable land use and recovery, and thus moving towards a landscape model of conservation will be most effective in securing the future for biodiversity in general and for the tiger and its habitat in particular. The local community will require its stakes to be identified in the entire process of such an inclusive mode of conservation based essentially on an active recruitment and retention of patrons locally, regionally, nationally and globally, working towards a common goal of saving the tiger in the wild. This will propel them to transit towards a protective attitude and identify their own economic growth along with the conservation of the tiger.

The objective of the present paper is to establish theoretically the possibility of such an interactive approach in biodiversity conservation vis-à-vis human development.We attempt to theorize and claim that the long-term economic benefits to the people living in and around the reserves are intrinsically linked to the `economic' benefits to the tiger. We conclude that it is not possible to separate the interests of the tiger from those of the humans on any spatial or temporal scale, after having established non-conflict situation between tiger conservation and local development. We argue that economic development of the local populace and conservation of tigers are not antithetical, but are actually complementary in character.

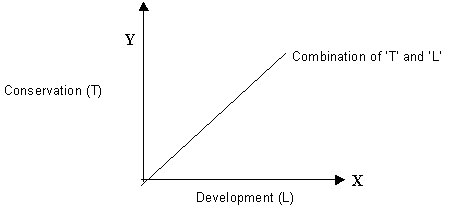

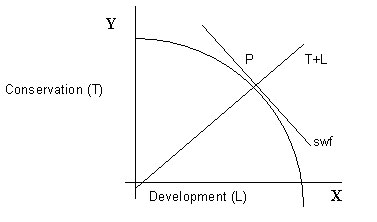

The current situation in most of the protected areas in India neither supports optimum tiger population 4 nor does it cater to the needs of the local population optimally in a sustainable mode. This is an inefficient situation. Applying theory from Environmental Economics, one can construct a Utility Possibility Frontier (UPF), with `T' on Y-axis and `L' on X-axis. Point C indicates the maximum number of tigers (proxy for conservation) that the reserve can sustain and support exclusively. D denotes the maximum forest produce (proxy for development) that can be harvested from the PA exclusively.

Fig.2. Production Curve

We shall follow the theoretical construct in the following three steps:

1. Constructing the UPF (data and model).

2. Constructing the Productivity Function (data restricted to model), and its reduction to dimensionless quantity. Depending on the production of T and L gathered from field data, the actual slope of the production function line will be determined as m = -a/b. Imposing this production function on the UPF, we get the point P, which we desire to establish as the Pareto optimality point.

3. From the current data, nature of the SWF curves could be known, which in general should be a conic, given by ax 2 + by 2 + 2hxy + 2gx + 2fy + c = 0,(1). The level curves of the current SWF in general and the maximal SWF in particular need not be tangential to UPF at P. This means that by merely increasing the quantum of overall allocation of resources to the PA on the one hand and keeping the ratio of share of these between T and L unchanged on the other does not lead the situation to attain optimality. It therefore becomes necessary to modify the SWF suitably, so that it remains/ becomes tangential to the UPF at the point P. The modification in SWF, reflected in terms of the constants involved in equation (1), should then be appropriately interpreted to reflect in the corresponding change in the management strategy for a balance of sustainability vis-a-vis conservation.

The equilibrium point will be given by intersection point of UPF = SWF = productivity curve (Fig.3).

Fig.3. UPF= SWF= Production Curve at P.

Based on this theoretical model, it is possible to optimize land-use in PAs on the basis of the data input from any tiger reserve because theoretically there exists an equilibrium point that will be obtained at the intersection point of UPF, social welfare function SWF and the productivity curve. Questions like `is it possible to establish Pareto optimality for utility functions of the local community and the tiger', or `is it possible to find an optimal forest area for a given community's forest-based needs, (as is in the case of tiger) ensuring sustainability', can be attempted with the help of hard data collected from primary or from secondary sources.

The specific objectives in that case could be to construct the Utility Possibility Frontier, the Social Welfare Functions and the Production Functions. For doing so one would need to:

And thus construct utility functions for both.

II. Identify the limits of exclusive conservation efforts and exclusive development efforts.

III. Identify contribution to the forest (defined as production function) of

Balakrishnan, M. and Ndhlovu, D.E., 1992. Wildlife utilization and local people case study in Upper Lupande game management area, Zambia. Environmental conservation, 19 (2): 135-43.

Bishop, K., A. Phillips, and L. Warren, 1995. Protected for ever? Factors shaping the future of protected area policy. Land Use Policy 12 (4): 291-305.

Fernandes, W., (ed.) 1996. Drafting a People's Forest Bill, Indian Social Institute, New Delhi.

Guha, R., 1989. Radical American environmentalism and wilderness preservation, a Third World critique. Environmental Ethics, 11: 71-83.

Guha, R.,1989 a. The Unquiet Woods, Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

Guha, R. and M. Gadgil, 1996. "What are forests for" in Fernandes.

Pathak, N. and A. Kothari, 1998. Sharing benefits of wildlife conservation with local communities: Legal implications. Economic and Political Weekly, XXXIII, (40): 2603-2610.

Seidensticker, J., S. Christie, and P.Jackson, 1999. Approaches to tiger conservation, in Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human Dominated Landscapes:

Eds. J.Seidensticker PJackson & S.Christie. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Thapar,V. (Ed.), 2001. Saving Wild Tigers. Permanent Black, New Delhi.

1 SHODH, The Institute for Research and Development,

50, Puranik Layout, Bharat Nagar, Nagpur - 440001

Maharashtra, INDIA

Tel. No. 91-712-555625.

E-mail:

2 Conservator of Forest (Evaluation), Government of Maharashtra, Nagpur.

3 In the present paper, the IUCN definition of PA has been adhered to: An area of land and/or sea especially dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity and of natural and associated cultural resources and managed through legal or other effective means. (WCMC: www.wcmc.org).

4 By an optimality of tiger population is meant the viable breeding as well as juvenile population supported by the domain forest. This capacity is determined through Velhurst's equation (or modified if needed, like Lotka-Volterra equation):