0429-B1

Boris Romaguer[1]

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has principally been attributed to the transformation of the forest into agricultural land. Only recently has forestry become an important contributor to deforestation. Forestry in Amazonia was slow to get underway primarily because of the high cost and technical difficulties associated with timber extraction in tropical ecosystems. Now however, forestry is becoming ever more prevalent in the development of the region. The major trends emerging from this sector are: selective logging, plantations, sustainable yield management and very recently, sustainable forest management. All these trends have their advantages, but sustainable forest management seems more likely to incorporate sustainable development and environmental conservation. Nevertheless, Brazil faces numerous barriers to the implementation of sustainable forestry in Amazonia. This paper presents the most important barriers, along with possible opportunities for achieving sustainable forestry, in five categories: environmental, technological, sociological, economic and political. It concludes that the most important challenges are political in nature and that these should be prioritized if forestry is to contribute to the sustainable development of the region.

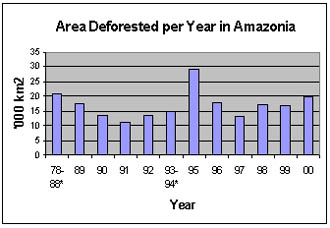

The Brazilian Amazon, an administrative area of 5 million km2 henceforth referred to as Amazonia, is renowned worldwide for its exceptionally rich biodiversity and for being one of the world’s largest remaining area of pristine tropical forests. It is also well known for its alarming rate of deforestation. Indeed, the average annual deforestation rate in Amazonia during 1978-1988 was 20 000 km2. Although this rate declined at the beginning of the 1990’s, it has since increased again and the latest figures indicate 19 836 km2 were cleared from 1999 to 2000 (Figure 1).

Historically, governmental incentives to populate the area and to convert it to agricultural lands were the major forces behind this deforestation. However in recent years, the tax incentives and subsidies that prompted this deforestation have been reduced. Besides the pressure of agriculture, at present, mining, industrial activities and especially logging for timber are becoming increasingly significant in the deterioration of forests in Amazonia. Although all these human activities exert a significant pressure on Amazonia’s forest ecosystems, this paper focuses exclusively on forestry.

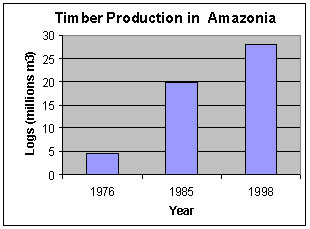

Some factors responsible for the emergence of forestry in Amazonia include the increasing commercial value of tropical trees, and their increasing demand in southern Brazil and in industrialized countries (mainly Japan, Europe and the United States). Other factors include the gradual depletion of forests in Southeast Asia and southern Brazil as well as the fiscal incentives in the lumber sector provided by the Brazilian government. Consequently, the timber production has significantly increased in Amazonia (Figure 2), particularly for export.

Figure 1. Area deforested per year in Amazonia.

(* indicates annual average). Source: INPE, 2001

Figure 2. Timber production in Amazonia.

Source: Barreto and Verissimo, 1999.

Since Amazonia is essentially composed of tropical forests, which are inherently complex systems, carrying out sustainable forestry in such ecosystems can be considerably more challenging than in temperate and boreal forests. Challenges include: large number of tree species, many of which being non-commercial; rapid and luxuriant growth of vines and creepers in the open spaces created by felling; fragility of the soils and its vulnerability when fully exposed; difficulties of access; and difficulties with natural regeneration. Consequently, the cost for sustainably managing tropical forests is higher than in temperate and boreal forests, which makes it particularly difficult when the countries possessing tropical forests tend to have fewer financial resources.

The forestry trends emerging in Amazonia are unsustainable selective logging, plantations and to a very limited extent, sustainable yield management and sustainable forest management.

Selective logging, where the most valuable species are extracted, has become the most common form of forestry in the region. This type of selective logging is done unsustainbly in Amazonia as it does not take any precautions to regenerate the tree species that were extracted. According to a study carried out in 1999, more than 10 000 km2 of forests in Amazonia were stripped of their most valuable trees. This area corresponds to nearly half of the total area deforested annually. Selective logging started in the inundated areas (várzea) and has since the 1970’s expanded to the non-inundated areas (terra firme). However, research suggests that selective forestry should be maintained in the várzea as much as possible because they have fewer tree species; are densely stocked with timber; grow more rapidly and the damage to the canopy and ground during logging is less severe than in terra firme.

Forest plantations are often hailed as the solution to the silvicultural problems associated with the tropical forests. Indeed, they are more productive and are capable of greater final wood volume per unit area, reducing the area of human disturbance. However, plantations in Amazonia tend to be established on natural forests instead of on already degraded land, which reduces the local biodiversity. Furthermore, since plantations tend to be composed of monocultures, they are vulnerable to environmental disturbances such as soil fertility, climate, disease and pests, the latter two being particularly prevalent in the tropics,. All the attempts of establishing large-scale plantations in Amazonia have failed. Examples include the rubber plantation of Fordlandia that was abandoned after a fungal outbreak and the Jari plantation of non-native softwood species which gave yields much lower than expected. More recently, 50 000 km2 of natural forests are being replaced by plantations in order to provide charcoal in the Projeto Grande Carajás and this project is likely to be doomed by natural disasters.

Sustainable yield management focuses on providing sustainable amounts of timber. This type of forestry was not initially successful in Amazonia because the Brazilian government chose to promote forest plantations and agriculture by various incentive measures. Several large-scale sustainable yield management projects in Amazonia have failed, namely the pilot project initiated by FAO and the Brazilian government of the Tapajós National Forest.

Sustainable forest management strives to preserve not only timber resources but also biodiversity and other natural services such as aquatic and climatic systems. In effect, this management, also known as “reduced-impact logging” is a refinement of sustainable yield management based more on a holistic ecosystemic multi-resource, and multi-service approach. Examples that come closest to such management are the extraction techniques employed by Precious Wood in Itacoatiara near Manuas and the Rosa Group in Paragominas which is now applying for certification by the Forest Stewardship Council.

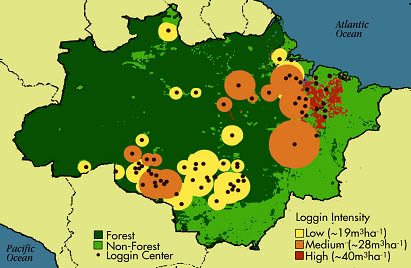

Although precise data on the exact location and scale at which these forestry patterns are conducted is not available, we do know that the more intensive forestry tend to be practiced on the periphery of the human encroachment on Amazonia where ports and roads are readily accessible and that the least extensive practices are located more toward the interior of the forest (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Patterns of forest logging in Amazonia.

Source: Nepstad et al., 1999.

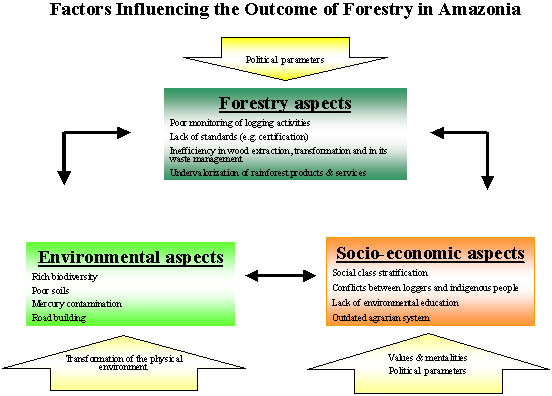

Amazonia will have to surmount various barriers in order to establish sustainable forestry. The most notable examples of environmental barriers include fragile soils and biodiversity as well as mercury contaminations caused by soil erosion after cuts. In terms of technical barriers, difficulties encountered by foresters include monitoring and assessing logging activities; inefficiency in wood extraction, transformation and in its waste management. Sociological barriers include corruption; urban migration to the region; and an outdated agrarian system. Economic barriers include uncontrollable timber prices; inappropriate stumpage fees; and the undervaluation of rainforest goods and services. Important political barriers include an absence of a central land register; as well as underfunded and overburdened governmental institutions, resulting in their inability to enforce existing laws and regulations.

Fortunately, there are also numerous opportunities for sustainable forestry in Amazonia. Environmental opportunities include shorter growth cycle of trees allowing faster regeneration of timber; higher quality wood in some tree species; and milder climate making agroforestry more feasible than in temperate forests. Technical opportunities include adoption of standards such as certification; technological transfer for better monitoring and harvesting equipment; and promotion of non-timber forest products. Sociological opportunities include raising public awareness of the benefits of forest conservation and ecotourism; and educating the forest workers and managers of the importance of work safety and sustainable forestry practices. Interesting economic opportunities include certification; and the debt-for-nature swap where industrialized nations agree to reduce the debt of a rainforest country if the latter agrees to use an equal amount of local currency to fund environmental programmes. An important political opportunity identified was increasing international cooperation between non-government organisation, bilateral and multilateral donor agencies in the forestry sector. Other political opportunities include placing mahogany in appendix II of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species so as to force forestry operations that harvest protected species to close down; eliminating subsidies to unsustainable development project such as the Projeto Grande Carajás or further transamazonian highways; implementing the existing forestry laws, norms and regulations; as well as reinforcing the protection of indigenous lands.

Figure 4. Schematic representation of how the varying factors (barrier and opportunities) hereto identified influence the forestry practices in Amazonia. Four measurable challenges were arbitrarily selected to represent each category. The political challenges have been included as outside parameters namely because of their more unquantifiable and unpredictable nature. Notice their predominance in influencing the system.

Forestry in Amazonia has great potential and to exclude it from the sustainable development of this basin would be unrealistic. Indeed, forestry will continue to be a major driving force in the region’s development. The question is not whether forestry can be stopped but rather how it can proceed in a more sustainable manner.

For the sake of protecting forest ecosystems, sustainable forest management appears to be the most appropriate kind of forestry. However, given the socio-economic situation of the region, its predominance in the near future is uncertain and it is likely that uncontrolled selective logging will continue to be the main type of forestry. As for plantations, the Jari and Carajás experiences indicate that large-scale plantations are unlikely to be sustainable in the long run. Thus, if plantations are to be chosen, they must be done on a much smaller scale, if at all.

The challenges that lie ahead of Brazil are numerous and great, and the path for sustainable forestry will certainly not be easy. Nonetheless, these challenges are not insurmountable and with proper interventions either in the environmental, technical, socio-economic or political sector, there is hope for the sustainable management of Amazonia’s forests. The vastness of Amazonia is an advantage in itself in that it will buy time for politicians, societies and scientists to review their development. This precious time will hopefully enable Brazilians to learn how to use their natural resources sustainably. Even if the present rate of deforestation goes unabated, Amazonia will probably be one of the last frontier forest to be cut down in the world. A lot can happen within this time frame. Indeed there is hope when one looks at Sweden for example, one of Europe’s poorest countries at the turn of the last century, which overexploited its forests. It has now become a model in many aspects of silvicultural management. The fact that there is peace among South American countries and that education is making progress is also encouraging.

The barriers and opportunities examined reveal that the most decisive forces in determining the path of forestry sustainability are political in nature. Indeed, although the scientific knowledge pertaining to tropical forest management may be incomplete (e.g. forest growth dynamics, precise location and area of the different forestry practices), what is most urgently needed at the moment is the political commitment to stop the forest crisis of Amazonia.

This paper has identified the major barriers and opportunities facing sustainable forestry in Amazonia. The next step would be to assess their relative importance. To achieve this, it would be appropriate to build on the schematic diagram hereto by using a dynamic systems model, as developed by Deaton and Winebrake (2000), in order to quantify and ultimately prioritize these challenges.

I am grateful to Professor Robert Davidson and Professor Marc Lucotte for their help and inspiration, as well as for the extraordinary hospitality of the inhabitants of Amazonia that I encountered.

Barros, A. C. and Uhl, C. 1995. Logging along the Amazon river and estuary: Patterns, problems and potential. Forest Ecology and Management 77 pp. 87-105.

Browder, J.O. 1988. Public policy and deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Public Policies and the Misuse of Forest Resources, eds. R. Reppetto and M. Gills, pp.247-297. Cambridge University Press, New York. In: Parayil, G. and Tong, F. 1998. Pasture-led to logging-led deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: The dynamics of socio-environmental change. Global Environmental Change 8(1) pp. 63-79.

Deaton, M. L. and Winnebrake, J. O. 2000. Dynamic modeling of environmental systems. Springer-Verlag, New York.

Dolbec, J., Mergler, D., Roulet, M. and Lucotte, M., 2000. Sequential Analysis of Hair Mercury Levels in Relation to Fish Diet of an Amazonian Population, Brazil. The Science of Total Environment, March 2000.

FAO 1993. The Challenge of Sustainable Forest Management: What Future for the World’s Forests?. FAO, Rome.

FAO 1997. State of the World’s Forests 1997. FAO, Rome.

Fearnside, P. M. 1990. Land uses in Brazilian Amazonia. In: Anderson, A. B. 1990. Alternatives to Deforestation. Colombia University Press, New York.

Fearnside, P. M. 1993. Deforestation in Brazilian Amazonia: the effect of population and land tenure. Ambio 22(8) pp. 531-568.

Fearnside, P. M. 1995. Sustainable Development in Amazonia. Pp. 207-224. In: Kosinski, L. A. (ed.) Beyond ECO-92: Global Change, the Discourse, the Progression, the Awareness. International Social Science Council (ISSC), United Nations Educational and Scientific Organization (UNESCO), Paris, and Editora Universitária Candido Mendes (Educam), Rio de Janeiro.

Glastra, R. (ed.) 1999. Cut and Run: Illegal Logging and Timber Trade in the Tropics. International Development Research Center, Ottawa.

Hanan, S. A. and Batalha, B. H. L. 1995. Amazônia: Contradições no Paraíso Ecológico. Cultura Editores Associados Ltda, São Paulo.

Hecht, S.B. and Cockburn, A. 1985. The Fate of the Forests: Developers, Destroyers and Defenders of the Amazon. New Left Press, Portland.

Hummel et al. 1994. Diagnóstico do subsetor madeireiro do Estado do Amazonas. Instituto de Desenvolvimento dos Recursos Naturais e Proteção Ambiental/Serviço de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas do Amazonas, Manuas. Cited in: Hanan, S. A. and Batalha, B. H. L. 1995. Amazônia: Contradições no Paraíso Ecológico. Cultura Editores Associados Ltda, São Paulo.

IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geographia e Estatística). 1999. In Camargo, L. (ed.) Almanaque April 2000: Brasil. 2000. 26 edition.

INPE (Instituto de Pesquisas Espaciais) /IBAMA (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis). 2001. Relatório Amazônia Desflorestamento 1995-2001.

IPAM (Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia). 1999. Projeto Várzea: Estratégias de Pesquisa e Intervenção para o Manajo dos Recursos Naturais de Várzea na Amazônia. Santarém (Brochure).

IPEA (Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada). 1999. Cited in Camargo, L. (ed.) Almanaque April 2000: Brasil. 2000. 26 edition.

Jordan, C. F.(ed.) 1987. Amazonian Rain Forests: Ecosystem Disturbance and Recovery. Springer-Verlag, New York.

Kengen, S., and Graça, L. R. 1999. Forest Policies in Brazil. Pp. 256-265. In: Palo, M. and Uusivuori, J. Kluwer (ed.) 1999 World Forests, Society and Environment. Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

Lele, U., V. Viana, A. Verisimo, S. Vosti, K. Perkins, and S. A. Husain. 2000. Brazil. Forests in the Balance: Challenges of Conservation with Development. Evaluation Country Case Study Series. World Bank Operations Evaluation Department, Washington, D. C.

Mery, G. 1999. Latin American Forests, Societies and Environments. Pp. 222-229. In: Palo, M. and Uusivuori, J. Kluwer (ed.) 1999 World Forests, Society and Environment. Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

Monbiot, G. 1991. Tips for the trees. Geographical Magazine 63 (11), 22-29. In: Parayil, G. and Tong, F. 1998. Pasture-led to logging-led deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: The dynamics of socio-environmental change. Global Environmental Change 8(1) pp. 63-79.

Moran, E.F. 1992. Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon (Occassional Paper No. 10, Series on Environment and Development), Indiana University, Bloomington. In: Parayil, G. and Tong, F. 1998. Pasture-led to logging-led deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: The dynamics of socio-environmental change. Global Environmental Change 8(1) pp. 63-79.

Moran, E.F. 1995. Rich and poor ecosystems of Amazonia: An approach to management. In: Nishizawa, T. and Uitto, J. (ed.) 1995. The fragile tropics of Latin America: Sustainable management of changing environments. United Nations University Press, Tokyo.

Nepstad, D. C., A. Verissimo, A. Alencar, C. Nobre, E. Lima, P. Lefebvre, P. Schlesinger, C. Potter, P. Moutinho, E. Mendoza, M. Cochrane, and V. Brooks, 1999. Large-scale Impoverishment of Amazonian Forests by Logging and Fire. Nature 398 (6727) p. 505-508.

Parayil, G. and Tong, F. 1998. Pasture-led to logging-led deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: The dynamics of socio-environmental change. Global Environmental Change 8(1) pp. 63-79.

Rankin, J. M. 1985. Forestry in the Brazilian Amazon. In: Prance, G. T. and Lovejoy, T. E. 1985. Key environments: Amazonia. Pergamon Press, New York.

Roulet, M., Lucotte, M., Guimarães, J.-R. and Rheault, I. 2000. Methylmercury in water, seston, and epiphyton of an Amazonian river and its floodplain, Tapojós River, Brazil. The Science of Total Environment. March 2000.

Shemo, D. J. 1996. Brazil’s rain forest is under the ax: new figures show increased losses since Earth summit in Rio. International Herald Tribune, 13 September 1996 pp.1. In Parayil, G. and Tong, F. 1998. Pasture-led to logging-led deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: The dynamics of socio-environmental change. Global Environmental Change 8(1) pp. 63-79.

SUDAM, 1998. Demografia da Amazonia legal: população nos anos 1970/1996, segundo as unidades da federação.

Svanqvist, N. H. 1992. The Timber Industry Perspective. Cited in: Downing, T. E. et al. 1992. Development or Destruction: The Conversion of Tropical Forest to Pasture in Latin America. Westview Press, Boulder and Oxford.

Tyler, C. 1990. Laying waste. Geographical Magazine 62 pp. 26-29. In: Parayil, G. and Tong, F. 1998. Pasture-led to logging-led deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: The dynamics of socio-environmental change. Global Environmental Change 8(1) pp. 63-79.

Uhl, C. et al. 1997. Natural resource management in the Brazilian Amazon, an integrated research approach. Bioscience 47(3) p.160-168.

Uhl, C., P. Barreto, A. Verrissimo, E. Vidal, P. Amaral, A. C. Barros, C. Souza, J. Johns, and J Gerwing,. 1997. Natural resource management in the Brazilian Amazon, an integrated research approach. Bioscience 47(3) p.160-168.

UNDP (United Nations Development Program). 1999. In: Camargo, L. (ed.) Almanaque April 2000: Brasil. 2000. 26 edition.

World Resource Institute. 1998. Aracruz Celulose S. A. and Riocell S.A.: Efficiency and Sustainability on Brazilian Pulp Plantations. In: MacArthur Foundation, 1998. The Business of Sustainable Forestry: Case studies. John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Chicago.

| [1] Institut des sciences de

l’environnement, Université du Québec à Montréal,

C.P. 8 888, Succ. Centre-Ville, Montréal, Québec, Canada,

H3C 3P8. Email: [email protected] |