0581-A1

Augusta Molnar[1]

From its inception, forest certification has aimed to address social as well as environmental goals.

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), its certifiers and supporting donors aggressively supported community certification. About 50 community enterprises have been certified worldwide, covering 1.1 million ha out of 30 million FSC-certified ha, and a number of certificates are in process. In addition to direct certification, many communities living in or depending on forest resources have benefited from certification by gaining a "seat at the table" in the certification of public and private forests and enterprises.

This review looks at the experience with communities and certification, first in a series of systematic reviews titled "A Decade of Certification: Reflecting on the Way Forward" and three set of impacts and issues: (a) for communities whose forests or enterprises are undergoing certification; (b) for communities who live in or depend upon forests being certified to a third party; and (c) relevance of the certification instrument for forest communities and forest dwellers not yet involved in the process.

Recent debates over the certification of state-owned forestry operations in Asia include unresolved dilemmas over the treatment of high-conservation-value forest, local property rights, and labor conditions. Another growing tension is between increasing market share of certified wood products, and maintaining sufficiently rigorous standards for the instrument's credibility. The way forward for the next decade must address these tensions.

The development of the forest certification instrument combined with leadership from the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), marks a critical turning point for the forest products industry. It signals the end of an era when the industry's operating imperatives were based on abundant wood supplies and ushers in an era defined by the increasing limit on forest resources in the future - both physically and politically. From its inception, forest certification aimed to address social as well as environmental goals. In addition to the 49 existing Communal Forest Management Certificates (FM) a number of communities are in the process of certification. In some commercial enterprises, communities have actively negotiated important worker conditions and rights, guarantee of better access to forests for their livelihoods, and, more recently, provision of professional services.

Certification's effects cannot be measured in hectares or premiums, but nonetheless are powerful, including giving greater voice to indigenous groups historically marginalized in the forest debate. Certification has created space for broader participation and continuous adaptation in forest management and conservation. Regional standards setting groups have convened industry, the environmental community, and local communities in an unprecedented way.

This review looks at the experience with communities and certification, the first in a series of systematic reviews titled "A Decade of Certification: Reflecting on the Way Forward". There are three set of issues: (a) the impacts and issues for those communities whose forests or enterprises are being or have the potential of being certified; (b) the impacts and issues for those communities who live in or depend upon forests being certified to a third party; and (c) the impact and relevance of the certification instrument for forest communities and forest dwellers not yet involved in the process.

For the purposes of this review, community enterprises include any form of community-based forest management enterprise where communities are involved in the planning, management or overall control of the operation. Community-company ventures-- where communities provide services or share tasks, investment, and benefit--are a subset.

Communities are attracted to certification in search of price premiums for their timber and wood products, of donor financing for their enterprises, and of legitimacy as responsible forest managers in countries that seek to place larger areas of forests within restricted biological reserves. At the same time, communities operate in an increasingly competitive market. Commercial plantations established in different geographic regions of the world over the past few decades are changing the nature of the pulp, paper, and wood supply and making it harder for small-scale producers with natural forest to compete in the marketplace.

The nature of community forest management and community forest enterprises is diverse. Some Indigenous Peoples maintain a long historical relationship with a forest, currently adapting to arrival of outsiders and internal population growth. Some communities have a long history of forest management, even when formal tenure recognition and creation of community enterprise may be recent-India, Indonesia, or Nepal. Other communities only recently acquired tenure rights and formed forest-based enterprises in recent decades.

The literature and certifying bodies document a growing paradox between loosening standards for community certification and tightening standards around third-party forest certification for industry, and government forests. (IMAFLORA, 2002; Irvine 2000, Bass, et al 2001, van Dam 2002; Carrere 2001) Despite strong demand for simplification of procedures for small enterprises, the demand for longer and more detailed assessments creates a rising bar for social and environmental criteria. NGOs are particularly concerned by the certification of industrial and state enterprises where land tenure rights of indigenous peoples and other local residents are not established. Recent debates over the certification of state-owned forestry operations in Indonesia include unresolved dilemmas over the treatment of high-value conservation forest, local property rights, and labor conditions.

Communities have multiple interests in this debate. Those with forest enterprises and secure tenure do not want to be left out if certification gains ground as a condition of market participation or tenure access. Forest dependent communities want to guarantee rights and benefit share, either from traditional uses or new employment and partnership opportunities.

The range of communities involved in certification are:

community-based forest enterprises as in Mexico or Guatemala

community players in company-community ventures for managing, harvesting or processing,

community partners in company-community ventures, such as the Iisaak joint venture;

community stakeholders in public consultations on commercial operations, including NTFP collectors,

communities employed as laborers in industrial forestry operations

communities of indigenous peoples seeking recognition of land and resource rights in forests undergoing certification.

The benefits and impact of forest certification differ by category, geography, tenure regime, and community enterprises.

Table 1: Progress in the FSC Community Certification (August 2002)

|

Country |

Number |

Area |

Notes |

|

Mexico |

21 |

517,208 |

|

|

Guatemala |

9 |

245,353 |

|

|

Germany & Austria |

7 |

22,594 |

(mainly city-town forests) |

|

USA |

5 |

220,185 |

Three Native-American |

|

Canada |

2 |

88,084 |

Both First Nations |

|

South Africa |

1 |

1,740 |

|

|

Zimbabwe |

1 |

24,850 |

|

|

Sweden |

1 |

1,450 |

|

|

Brazil |

1 |

900 |

|

|

Bolivia |

(1) |

(53,000) |

Pending recertification |

|

Honduras |

2 |

13,868 |

|

|

Philippines |

1 |

14,800 |

|

|

Papua New Guinea |

1 |

4,310 |

|

Source: FSC Information Site, www.fsc-info.org, 30 August 2002

Mexico and Guatemala have the clear majority of certification examples. Mexico's land reform favors community certification as it recognized tenure of indigenous communities and land reform collectives (ejidos) to 70 or 80% of Mexico's total forest area. Certified communities in Mexico could double or triple in a near future.

In Guatemala, certification has occurred in the Petén, linked to community concessions in the Maya Biosphere Reserve. In Bolivia, Brazil and Ecuador, communities are involved in resource or biodiversity conservation programs with community enterprise development or forest certification objectives, with twenty Brazilian Amazon communities seeking certification. Bolivia forest sector reforms enabled new communities to manage forests, without yet creating new certification.

In the United States, three Native American enterprises within the Inter-Tribal Timber Council have been certified (Menominee, Stockbridge Munsee, and the Hoopa Valley tribes), with other tribes not yet meeting requisite technical or business management standards. The Inter-Tribal Timber Council has formally requested support from the government to help all tribes reach certification, as part of the "trust" relationship to these nations.

Canada presents an interesting juxtaposition, given more limited Indigenous forest tenure. Two current examples are Pictou Landing in Nova Scotia, a small community holding interested in sustainability, and Iissak, a public-private joint venture on a commercial concession area with majority First Nations ownership. Forest certification helps define the Indigenous Peoples tenure debate, providing them greater decision-making in public concession management and promoting greater rights recognition.

Zimbabwe, Poland, Papua New Guinea, Philippines and South Africa, have isolated examples, but there are none where community forestry has rapidly expanded with government devolution of forests, such as India, Nepal, Tanzania, Ghana, Uganda, Vietnam, or China.

There are known challenges for communities to become and remain certified:

a) high cost of initial certification and annual auditing relative to profits (Bass 2001; Irvine 1999);

b) cost of implementing recommended actions and documentation (Irvine 1999; Bass 2001; Nussbaum 2001);

c) reductions in donor financing (IMAFLORA 2002; Chapela and Madrid 2002; Santa Cruz 2001);

d) fragility of the community institution with certification imposing short timelines to institution improvements (van Dam 2002; Bass et al 2001);

e) some communities encouraged to upscale enterprises risking financial stability and community tension (Soza, Aguilar, Chapela and Madrid; and Robins and Roberts 1998);

f) few price premiums for certified products, with limited delivery of desired quantity/ quality (Santa Cruz 2001, Irvine 1999);

g) community products compete with increasingly abundant, cheaper plantation wood (Poschen 2002; Leslie 1999);

h) smaller communities forests cannot meet current procedures (Nussbaum 2001, Irvine 1999); and

i) certification not suited to highly diversified community agro-forestry economies where tropical forests require costly studies and monitoring (Chapela and Madrid 2002).

Key issues reviewed include: affordability, certification as a pre-condition of community tenure rights, community values in standards and criteria, and applicability to complex community setting where wood is only one economic product.

Affordability: Certification costs can represent a high proportion of total operational costs for communities, especially the first five years. Each of Mexico's communities have spent $ 10,000 annually including recommended actions; Guatemalan communities from 5 to 30% of their cost of operations ($ 5000 to $20,000). Brazil has subsidized using voluntary certifiers and having industrial-scale clients pay a premium. High cost of certification and recommended actions discourages Native American tribal enterprises from pursuing certification actively, even with available subsidies.

The cost issue relates to difficulties in creating sufficient demand for community wood, making enterprises unable to generate profits to make certification cost-efficient.

Simplification: A proposal under consideration in FSC simplifies certification of small enterprises, including communities by grouping enterprises for evaluation purposes and by establishing a set of thresholds by resource characteristics and harvesting intensity for modifying requirements like the timing of audits, preparation of detailed plans or documentation of activities. This will be a positive step forward, but some of the recommended procedures still require modification to community needs.

Recognition of Traditional Knowledge and Practices. Communities observe some certifiers do not respect traditional resource knowledge, community organizational processes or dynamics or their preferences for forest composition. Examples cited in case material include recommendations that impose inappropriate external participation and forest practice standards and untimely enterprise management criteria.

Markets and Challenges. Community production in Mexico and Brazil faces growing competition with plantation timber. implying a need for access to markets with community comparative advantage, where variability in wood characteristics, long rotation, natural species, and more finished grades are desired. This will require more sophisticated planning and operations, and more collaboration. Communities with high value conservation forest have argued that they should be paid for environmental services, rather than losing income to become certified.

Certification as a Forced Requirement. Throughout Latin America, programs for biodiversity conservation are experimenting with linking community access to forests in protected areas and in buffer zones to forest certification. The community certification initiative in Guatemala's Petén region was driven by government and international agencies to create objective criteria for granting community concessions in and around the Maya Biosphere Reserve. Thirteen communities received long-term tenure to concession areas conditioned on their becoming and staying certified (Soza 2002). The Lomerío enterprise of CICOL in lowland Bolivia relied upon certification to validate indigenous forest rights after the 1996 Bolivian reform. Proponents of Indigenous Peoples' self development and CFM question linking tenure rights to certification, where other property owners do not have similar preconditions to their rights.

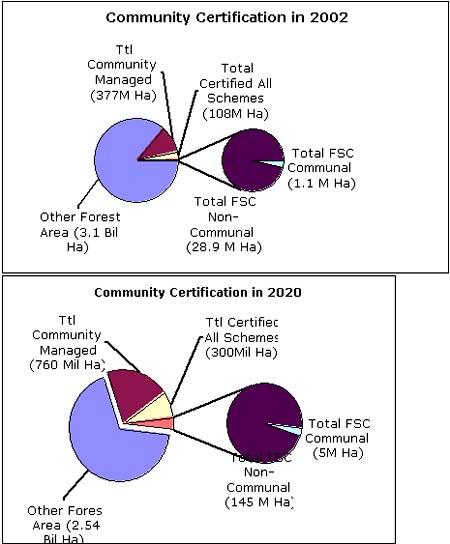

How Many Communities are Likely to become Certified? Despite significant gains in certification of community enterprises, due to efforts of Smartwood and SGS-Qualifor approved certifiers, the current trajectory remains limited. The extent of community forest ownership is expanding rapidly globally. With at least a quarter of the developing countries' forests community owned or managed (White and Martin 2002), the scale is enormous. For 24 of the 30 most forest-rich countries with tenure data, communities own or administer 377 million hectares out of the total 3.6 billion (11%). Excluding the developed countries from this list (where government ownership is greater), the percentage jumps to twenty-five percent. Indigenous forest communities are increasingly their efforts to gain legal recognition of their land and forest rights, while governments devolve responsibility to local levels. The current situation reflects a doubling of area under community ownership or administration in the last 15 years and analysts predict that this percentage will double again within the next fifteen years to nearly 800 million hectares.

Even simplifying procedures and criteria, many forest communities will not become eligible for certification. Should communal certificates quadruple by 2020, certified community-managed forest could quadruple to 200 communities with 5 million hectares. But this figure is relatively insignificant relative to the 377 million hectares of forest currently in community ownership or administration, or the anticipated 300-400 million additional hectares that will enter community control during the same period. Communities currently manage 10-12 million hectares of forest under Joint Forest Management in India, 2-3 million in Nepal under CFM, 100 Million in indigenous reserves in Brazil and another 20-30 million each in Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia. (White and Martin, 2002) Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Central America, Tanzania, Uganda, and Congo in sub-Saharan Africa have significant community forests, and U.S. Native American forests cover 16 million hectares. The province of British Colombia is testing long-term community tenure with new Community Forest Agreements (CFAs) in public lands.

Juxtaposing the world's forest with certified forest area shows a big gap between the extent of community managed forest and the future of community certification.

Table 3: Community Certifcation as a Percentage of World Forest Area

Multiplying community certificates five times equals 5% of all certified area, but this percentage will drop as public and private certification expand in parallel. This is only 1.1% percent of the world's area under community management or ownership (conservatively 377 Million hectares). If the world's community-managed areas doubles to 760 million hectares as projected, 5% or 5-10 million hectares of certified area in 2020 would be only 0.5-1% of community forest.

The Balance Sheet. Forest certification has evidently led to greater attention to forest tenure and livelihood rights, conditions of employment, and worker health and safety. However, the current structure of forest certification schemes precludes entry of many communities, even with simplification. Forest certification schemes should be examined for their congruence for communities and the certification instrument should be complemented by new options plus needed technical services and investment finance. Only a more effective strategy will reach communities who have the potential to benefit from forest certification and provide options for others.

External barriers must also be tackled, to remove or simplify policy and regulatory constraints and structural market barriers. Communities need better information on marketing and production. Complex management systems of communities need more complementary instruments, including for NTFP and zoning of the broader landscape tenure and uses.

The Way Ahead. Four areas need action:

First, a major strategic reassessment of the forest certification instrument and its alignment with its own strategic objectives to evaluate:

(a) the range of communities becoming certified;

(b) balance between social, environmental and economic concerns.

(c) costs and returns of community certification,

(d) flow of donor funds to community certification initiatives,

(e) emerging challenges--policy and regulatory barriers of small scale enterprises and market structures.

Second, a strategy for capacity-building and technical services to communities managing forests and interested in or entering into commercial enterprises.

Third, a new participatory space for communities and Indigenous Peoples to enter the dialogue.

Fourth, donors, multi-lateral finance institutions and national governments support analysis of alternatives to forest certification for community forest managers.

Bass, et al. 2001. Certification's impacts on forests, stakeholders and supply chains. Instruments for sustainable private sector forestry series. International Institute for Environment and Development, London.

Chapela, Francisco and Sergio Madrid. 2002. "La Certificación en Mexico: Los Casos de Durango y Oaxaca", unpublished case study and background paper.

Higman, Sophie y Ruth Nussbaum. 2002. How standards constrain certification of small forest enterprises, ProForest, London, Great Britain. <http://proforest.net>.

Irvine, Dominique. 1999. Certification and Community Forestry: Current Trends, Challenges and Potential. Background paper for the World Bank/WWF Alliance Workshop on Independent Certification, Washington, D.C. Nov. 9-10, 1999.

Jansens, Jan- Willem. 2002. The Sustainable Forestry Fund. paper presented at Global Perspectives on Indigenous Peoples' Forestry: Linking Communities, Commerce and Conservation, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada June 4 - 6, 2002,

Mayers, James and S. Vermuelen. 2002. Company-Community Partnerships: From Raw Deals to mutual benefits? International Institute of Environment and Development, London.

Robins, Nick and Sarah Roberts. 1998, Part 1:A New Deal for Trade, Environment and Development? in Environmental Responsibility in World Trade:The Workbook, presented to the British Council International Conference, 6-9 September 1998, London.

Smith, Peggy and Monique Ross. 2002. Policy Lessons & Innovations in Canada. paper presented at Global Perspectives on Indigenous Peoples' Forestry: Linking Communities, Commerce and Conservation, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada June 4 - 6, 2002

Smith, Peggy and Monique Ross. 2002. Accomodation of Aboriginal Rights: the Need for an Aboriginal Forest Tenure (Synthesis Report), Sustainable Forest management Network, University of Alberta, Canada, April 2002.

van Dam, Chris, 2002, Certificación Forestal, Equidad y Participación, Paper prepared the Participation Network CODERSA-ECLNV, August 5 to September 1, 2002.<http://www.red_participacion.com>

Von Kruedener, Barbara. 2000. FSC forest certification - Enhancing social forestry developments? In Forests, Trees and People Newsletter No.43, Uppsala

White, Andy and Alejandra Martin, 2002, Who Owns The World's Forests? Forest Tenure And Public Forests In Transition, Forest Trends and Center for International Environmental Law: Washington, D.C.

WWF-Bolivia.. 2001. Conference Proceedings. Manejo Forestal Comunitario y Certificación en América Latina". International Conference held in Santa Cruz, Bolivia from the 22 to the 26th of January, 2001

| [1] Sr. Research and Policy

Analyst, Forest Trends, 1050 Potomac Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20009.

Tel: 202 298-3006; Fax: 202 298-3014; Email: [email protected] |