0728-B4

Laura K. Snook[1], Cesar Sabogal, Marco Boscolo, Joyotee Smith, Maria Teresa Vargas, Lincoln Quevedo, Violeta Colan, Marco Lentini, Leonardo Sobral, Luiz Carlos Rodriguez and Adalberto Verissimo

While well-managed tropical forests have the potential to sustain timber production and environmental services, little is known about the degree to which sustainable forest management (SFM) practices are applied in the tropics, or what factors favour or impede their adoption by forest managers. To answer these questions, the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) supplied questionnaires to the owners/managers of timber industries and their foresters in Brazil, Bolivia and Peru. In Peru, small extractors harvest timber from areas < 1000 ha; in Bolivia, industries harvest from large concessions on national lands; while in Brazil, timber industries must own sufficient forest land to supply their mills.

Factors hypothesized to affect the adoption of SFM practices include the characteristics of the regulatory environment, of the various practices, and of the industries; and external factors such as the stage of development of the forest frontier and technical support. Preliminary analyses revealed that in Peru, extractors used relatively low-impact manual methods, but this is likely to change under a new forestry law that will favour large concessionaires. In Bolivia, adoption was correlated with an "index of regulatory pressure" combining legal requirements and ease of enforcement. In Bolivia and Brazil forest managers tended to adopt practices they perceived as having sustainability benefits.

Additional data will be collected through field evaluations to assess whether practices that are claimed to be used, are actually practised, and to obtain insights from fellers and skidder operators. The completed study should reveal how national forest management agencies and international development and conservation organizations can contribute to increasing the level of adoption of SFM practices in tropical forests.

Demands for goods and services from tropical forests are increasing in quantity (timber demand typically increases with development) and in breadth (NTFP's, biodiversity, carbon, water, etc.) (Nilsson, 1996; FAO 2001; Gardner-Outlaw & Engelman 1999; WWF 2001). Meanwhile, forest area per capita is declining in tropical developing countries due to population growth and forest loss (Nilsson, 1996: FAO 2001; Gardner-Outlaw & Engelman 1999; WCFSD 1999). Poor people depend on many forest resources (Byron & Arnold 1999), and in some countries the forest industry employs significant numbers of people and provides foreign exchange (FAO 2001). However, timber harvesting, poorly practiced, can degrade both future timber yields and forest resources and services used by other stakeholders (Johnson and Carbarle 1993; Bryant et al. 1997; Nepstad et al. 999).

Good forest management could reduce the negative impacts of timber harvesting and increase yields of desired products and services. However, it has been estimated that a negligible proportion of tropical production forests are managed to sustain timber yields along with other values and services (Poore et al. 1989; Bowles et al. 1998). Even practices demonstrated to be effective in reducing damage and sustaining future yields of timber and other biotic resources are practiced by a tiny minority of tropical forest managers (FAO 2001; Richards 2000).

International donors, development agencies, and researchers have invested in promoting the adoption of SFM practices in the tropics. The economic and environmental benefits of reduced impact logging (RIL) have been demonstrated in various tropical forests (ie. Pinard et al 2000; Holmes et al 2002). Yet little is known about the constraints that impede the widespread adoption of sustainable forest management (SFM). Debates have focused on the perceived financial disadvantage of SFM as compared to timber mining (Barreto et al.1998; Pearce et al. 2001; Rice et al. 2001), but few have analyzed the behaviors and reasoning of forest managers in specific situations (e.g., Karsenty 2001; Blate et al. 2001; Putz et al. 2000).

This paper summarizes preliminary observations from CIFOR research in three Amazonian countries which seeks to determine:

1. To what degree do forest industries managing forests apply practices to sustain forest productivity and environmental services? and

2. What factors influence their adoption of these practices?

The ultimate objective is to propose strategies, from legal/regulatory changes to training, encouragement of certification or guidance in business management, which would lead to increased adoption of good management practices by industries that use - and may be abusing - tropical forest resources.

We compiled information on the timber industry and the regulatory environment in each country (Tables 1 & 2) and developed 4 hypotheses about the factors that influence the adoption of SFM (Table 3). We selected and stratified the key management practices to be evaluated (Table 4) to test our hypothesis that practices are differentially "adoptable" due to their potential to benefit the producer in the short term. Within each country, our sample population of medium-sized industries was stratified by region and selected at random. Questionnaires developed by country teams for the owners/CEO's and head foresters of industries were applied to all operating industries in Peru, 1/3 of the Bolivian industries with forest concessions, and 45 industries in Pará, Brazil.

Table 1: Timber industries in Brazil, Bolivia and Peru

|

Parameter |

Bolivia |

Brazil |

Peru |

|

Area of production forest (Mha) |

28 |

310 |

21.5 (for concessions in 2002, under new law) |

|

Industries controlling forest area |

75 in 3 states (Santa Cruz, Beni and Pando), totaling 4.9 million ha |

294 in 4 states (Para, Mato Grosso, Rondonia and Amazonas), 714 in total |

31, (only 7 operative in mid-2001) in 3 states (Ucayali, Loreto, Madre de Dios) |

|

Area under management plans |

4.968 million ha |

3000 plans |

570,000 ha |

|

Number of industries with forests and transformation industries |

45 industries/86 concessions |

5000 industries |

10 industries |

|

Size of forests under management plans |

6,000 - 372,000 ha |

25 - 3 million ha |

2,600 - 49,620 ha |

|

Industrial capacity and volumes extracted |

372 sawmills, 1.59 million m3 in 1999 |

2,463 industries, 7 million m3 in 1997 from 72 centers in 6 states. |

Ucayali: 41 sawmills, 57 reprocessors, 14 parquet companies, 7 plywood factories; 1 post factory purchased roundwood from others. Only 2 industries harvested timber (3,300 m3) in 2000. Loreto: all raw materials from 1000 ha contracts. Only 4 industries extracted timber (64,242 m3) in 2000. |

|

Number of species extracted |

3-10/ha depending on forest type and region |

350 in total. Depending on region, 6-50/ha. |

48 in Ucayali, 27 in Loreto in 2000 |

|

Volume extracted/ha |

2-14 m3/ha depending on the forest type/region |

9-30 m3/ha depending on the region |

|

|

Destination of production |

Mostly domestic; 13% for export |

Mostly domestic, 3% for export |

Ucayali mostly domestic; Loreto domestic and export |

|

Production (FAO 2001) |

690,000 m3 (1999) |

66,885,000 m3 (1999) |

416,000 m3 (1999) |

|

Certified industries/has |

9 industries; 801,513 ha |

4 industries; 268,000 ha |

In process: 20,000 ha |

Table 2. The legal/regulatory framework for forestry in Bolivia, Brazil and Peru.

|

Key Parameters |

Bolivia |

Brazil |

Peru |

|

Legal Framework |

Forestry Reform 1996-97 (law and establishment of Superintendencia Forestal) |

Forestry Code 1965; Regulations 1986 |

Forestry Law and regulations 1976; Forestry Law and Regulations 2000 (not yet affecting sample population) |

|

Property rights |

> 80% concessions by private companies on public forest land; remainder ASL's, TCO's or private land |

>90% privately owned. Efforts under way to create national and state forests |

>90% under cutting permits for < 1000 ha in public forests; remainder in contracts for > 1000 ha. New law will provide for concessions and other arrangements. |

|

Resource Access |

Concessions on government land; ASL's on Municipal land; cutting permits on indigenous land (TCO's), and private properties |

On privately-owned forests: management plans; permits to clear and convert forest. On government-owned forests: auctions |

Under 1976 law, cutting permits for areas < 1000 ha; industrial contracts > 1000 ha; contracts for harvesting on National forests. New law: concessions/auctions |

|

Duration of rights |

40 year concession; 5 yr audits |

30 years or according to management plan |

10 years (old law) 40 years (new law) |

|

Requirements for forest management |

Management plan, Annual cutting plan, Annual reports, Payment by area; |

Management plan, Annual cutting plan, Own or rented area, Sufficient forest to supply industry |

Contract for harvesting < 1000 ha |

|

Transparency |

Area taxes reduce discretionary payments; Law publicly known; public decisionmaking |

|

|

|

Oversight mechanisms |

Superintendencia; Municipalities, Foresters responsible; Private individuals can denounce. |

IBAMA Environmental Crimes Law 1998; Increasing capacity for control since 2000 |

INRENA New mechanisms under new law, still being worked out |

Table 3. Four hypotheses about the adoption of SFM practices:

H1: Different levels of adoption in different countries reflect differences in the policy/regulatory environment for forestry and the implementing institutions.

H2: Different levels of adoption among industries within a country reflect differences among industries (ie. management capacity, vertical integration, or export-orientation).

H3: Different levels of adoption of specific practices reflect the "adoptability" of those

practices (ie. whether adoption yields a short-term benefit to the industry).

H4: Different levels of adoption reflect differences in additional factors including technical assistance, certification, national crisis, scarcity of timber, and stage of development of the forest frontier.

Table 4. Key SFM practices and their contributions to sustaining forest productivity and environmental services and other benefits over various time scales (short = current harvest; medium = next harvest; long = beyond second harvest).

| |

Practice |

SFM objective |

Other benefits |

Time frame of other benefit |

|

1. |

Careful road design and construction |

Reduce damage to site, rivers; increase efficiency |

Reduced cost of transport, damage to vehicles |

Short |

|

2. |

Reduced-impact harvesting/RIL (combining 2a-2d) |

Reduce damage to soil, rivers, future harvest trees |

Increased efficiency can reduce costs |

Short |

|

2.a |

Stock survey and mapping of harvest (and ideally, future harvest) trees |

Tool for planning skid trails to reduce damage, protect next harvest and seed trees |

Information useful for marketing and planning |

Short (medium (if next harvest trees included) |

|

2.b |

Skid trail planning and layout |

Reduce damage to soil, rivers, future harvest trees |

Increased efficiency, lower skidding costs |

Short |

|

2.c |

Directional felling |

Protection of next-harvest trees and seed trees |

Reduction of risk to faller and damage to felled tree |

Short |

|

2.d |

Vine cutting |

Reduced damage to residual trees; on residual trees, increase in growth and seed production |

Reduction of risk to faller and damage to felled tree |

Short |

|

3. |

Leaving, protecting seed trees |

Providing for regeneration |

Trees left provide volume for next cutting cycle |

Medium |

|

4. |

Respecting the annual cutting area |

Sustain annual harvests during the first cutting cycle; favor post-logging recovery |

Protect volumes for second cutting cycle. |

Medium |

|

5. |

Protecting the forest from fire, poaching, invasion |

Sustaining forest cover and productive capacity |

Protect future harvests |

Medium |

|

6. |

Monitoring growth |

Tool for sustaining yield by ensuring that cutting cycles provide for replacement of harvested trees |

Sustaining harvest volumes for second cutting cycle and beyond |

Medium |

|

7. |

Defining and respecting environmental buffer zones (ie along streams; steep slopes) |

Protection of water courses, biodiversity, and ecological processes underlying sustainability |

Long-term sustainability |

Long |

|

8. |

Establishing and respecting reserve areas within forest management units |

Protection of biodiversity and ecological processes underlying sustainability |

Long term sustainability |

Long |

|

9. |

Controlling hunting on forest management unit |

Protection of biodiversity and ecological processes underlying sustainability |

Long term sustainability |

Long |

Peru

In Peru, most producers are small contractors with short-term logging permits for < 1000 ha. They did not follow our defined SFM practices, but used manual methods and river transport that seemed relatively nondestructive. In future we will observe their harvesting operations to understand better whether they contribute to sustainability. For example, is their manual skidding, using other logs as tracks, low impact or unnecessarily destructive, due to the felling of other trees to use as skids?

This study has already yielded insights relevant to the ongoing development of regulations associated with the new Forestry Law in Peru: first, how to address the loss of livelihoods on the part of small extractors, who will be excluded from participating in timber harvesting under new provisions based on large concession agreements. Secondly, that measures should be considered to require/support the use of SFM practices to avoid a transition to more destructive logging as default low-impact practices are superceded when larger operators with machinery replace small, manual harvesters.

Brazil

Our preliminary analyses of data from 4 regions in Pará revealed that producers perceived that the major benefit of good management practices was sustaining the forest. This may reflect the fact that most own their forest lands outright (Table 2). Their principal complaint was the government's slow approval of management plans. Interest in good management or certification was strongly correlated with exports. Benefits of certification were perceived as market access, rather than a price premium.

Bolivia

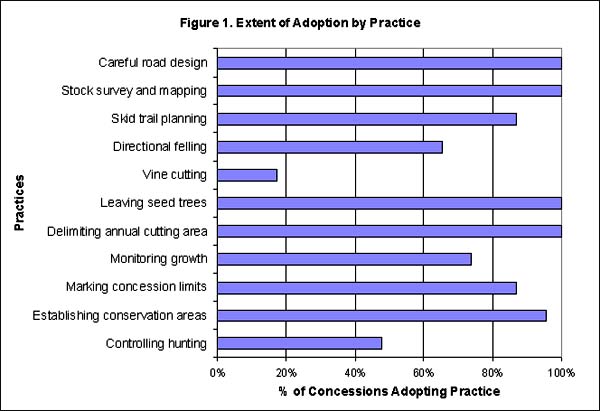

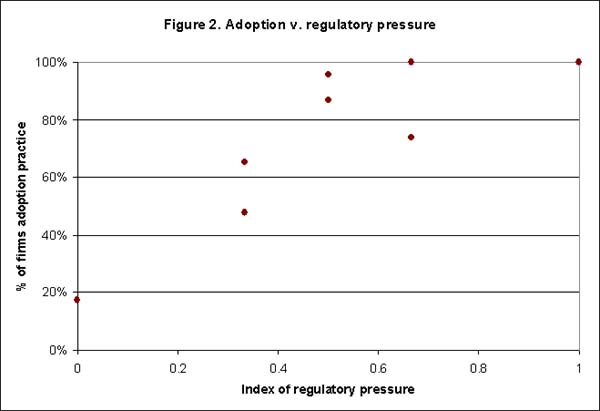

Data from 23 concessions in 3 major timber-producing regions revealed that adoption varied markedly among practices, and among firms (Figure 1). The most significant factor affecting the adoption of a practice was the legal and regulatory environment, expressed through an 'index of regulatory pressure'. This index varies between 0 and 1 and was derived from two factors: whether a given practice is mandated by law, and the ease with it can be enforced (see Boscolo et al. 2002). The results suggest that regulation, and especially enforceability, play a critical role in the adoption of SFM practices (see Figure 2).

Source: Boscolo et al. 2002.

Source: Boscolo et al. 2002.

Preliminary analyses suggest that the decision to adopt a given practice was driven more by the perceived effect of the practice on sustainability than by its perceived economic cost or benefit. If confirmed, this result suggests that increasing managers' awareness of the sustainability-enhancing impacts of forest practices is likely to motivate their adoption.

In 2002, questionnaires, observations and measurements will be applied to current harvesting operations and areas harvested in the past to: a) asses whether a "yes" answer on the questionnaires reflects good practices in the field; and b) gain additional insight into why or why not practices are used. Supervising foresters, skidder operators, and fellers, whose actions during timber harvesting most affect the residual stand and the potential for sustainability, will be interviewed. When combined with the first set of questionnaires, these data will permit more robust analyses and conclusions.

Within-country studies will shed light on the effects of the characteristics of the practices, of the industries, and of the external environment on the adoption of SFM practices. We will pool data from the three countries to reanalyze the importance of these factors, and compare the results among them to evaluate the impact on adoption of the legal and regulatory environment.

The only way to meet increasing needs for fiber while sustaining biodiversity and other environmental services from forests is to replace current destructive practices with SFM on the natural forests which currently provide for over 80% of our fiber needs (FAO 2001). From our research on timber industries in Peru, Brazil, and Bolivia, we are learning about the way they manage their forests, and the factors that influence their decisions. We expect to derive insights that can be translated into government policies and strategies for international aid to forestry to increase the likelihood that SFM will be applied to the millions of hectares of tropical forest harvested each year in the Amazon and beyond, to yield both production and environmental benefits for stakeholders in a spectrum of forest goods and services.

Funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), the Peruvian Technical Secretariat for International Cooperation of the CGIAR (CGIAR/STC) and the Ministry of the Environment, Brazil, with the collaboration of INRENA, Peru; and EMBRAPA, the Fundacao Florestal Tropical (FFT), and IMAZON, in Brazil.

Barreto, P., P. Amaral, E. Vidal, and C. Uhl. 1998. Costs and benefits of forest management for timber production in eastern Amazonia. Forest Ecology and Management 108:9-26.

Blate, M.G., Putz, F.E., Zweede, J.C. (2001) Progress towards RIL adoption in Brazil and Bolivia: Driving forces and implementation successes. International Conference on Application of Reduced Impact Logging to Advance Sustainable Forest Management. 26 February - 1 March 2001, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia.

Boscolo M., L. Quevedo & L. Snook (2002), What determines the adoption of good forestry practices in Bolivia? Draft of May 24, 2002. Presented at the First National Meeting on Forestry Research, June 25-27, 2002, Santa Cruz.

Bowles, I.A., Rice, R.E., Mittermeier, R.A., da Fonseca, G.A.B. (1998). Logging and tropical forest conservation, Science, 280: 1899-1900.

Bryant, D., Nielsen, D. Tangley, L. (1997). The last frontier forests: Ecosystems & Economies on the edge. WRI.

Byron, N. & M. Arnold (1999). What futures for the people of the tropical forests? World Development 27(5):789-805.

FAO (2001). State of the World's Forests, FAO.

Gardner-Outlaw, T. & R. Engelman (1999). Forest Futures. Population, Consumption and Wood Resources. Population Action International, 68 pp.

Holmes, T. P., G. M. Blate, J. C. Zweede, R. Pereira, Jr., P. Barreto, F. Boltz and R. Bauch (2002) Financial and ecological indicators of reduced impact logging performance in the eastern Amazon. Forest Ecology and Management 163:93-110.

Johnson, N. & B Cabarle (1993). Surviving the cut: Natural forest management in the humid tropics. WRI.

Karsenty, A. (2001) Economic instruments for tropical forests: the Congo basin case. London, UK: IIED/CIFOR/CIRAD. (Monograph) iv, 98p.

Nepstad, D.C., Verissimo, A., Alencar, A., Nobre, C., Lima, E., Lefebvre, P., Schlesinger, P., Potter, C., Moutinho, P., Mendoza, E., Cochrane, M., Brooks, V. (1999). Large-scale impoverishment of Amazonian forests by logging and fire, Nature 398: 505-508.

Nilsson, S. (1996). Do we have enough forests? IUFRO Occasional Paper No. 5.

Pearce, D., F. Putz, J. K Vanclay. 2001. Sustainable forestry in the tropics: panacea or folly? Forest Ecology and Management 5839:1-19.

Pinard, M.A., F.E. Putz, & J. Tay. 2000. Lessons learned from the implementation of reduced-impact logging in hilly terrain in Sabah, Malaysia. International Forestry Review 1(2:33-39).

Poore, D., Burgess, P., Palmer, J., Rietbergen, S., Synnott, T. (1989). No timber without trees: Sustainability in the Tropical Forest. A Study for ITTO. Earthscan Publications Ltd. London.

Putz, F.E., D.P. Dykstra, and R. Heinrich. (2000). Why poor logging practices persist in the tropics. Conservation Biology 14:951-956.

Rice, R. E., C.A. Sugal, S.M. Ratay & G.A.B. da Fonseca. 2001. Sustainable Forest Management: A review of conventional wisdom. Advances in Biodiversity Science Number 3. Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, CI, Wash. D.C. 28 pp.

Richards, M. (2000). Can sustainable tropical forestry be made profitable? The potential and limitations of innovative incentive mechanisms, World Development, 28(6): 1001-1016.

White, A. & A. Martin. 2002. Who owns the world's forests? Forest tenure and public forests in transition. Forest Trends/Center for Environmental Law, Washington, DC, 30pp.

World Commission on Forests and Sustainable Development (1999). Our Forests Our Future.

World Wildlife Fund (2001). The Forest Industry in the 21st Century. 19 pp.

| [1] Center for International

Forestry Research (CIFOR), P.O. Box 6596 JKPWB, Jakarta 10065, Indonesia.

Tel: 62-251-622-622; Fax: 62-251-622-100; Email: [email protected] |