S. SONTHEIMER,

Project International Consultant;

B. BIR BASNYAT,

Project PRA Specialist;

K. MAHARJAN,

Project Lead Gender Consultant

|

THIS IS THE STORY OF THE NEPALESE project on Improving Information on Women's Contribution to Agricultural Production for Gender-Sensitive Planning (GCP/NEP/051/NOR). It was essentially about three things: participation, gender and planning. Participation in the sense that rural men and women were actively involved in participatory planning exercises, using participatory rural appraisal (PRA) techniques, to glean information about their agricultural development needs. Gender in the sense of ensuring that both men and women had a voice in the planning exercise and that both sets of needs were recognized. And planning in the sense that community action plans (CAPs) were prepared as part of the PRA exercises. District-level planners and extension staff, who were in a position to respond to farmers' needs, participated in the process.

As a pilot exercise, the project was mainly concerned with testing a model for participatory and gender-sensitive planning at the bottom end of the planning ladder, i.e from the community to the district level. Although there have been many larger projects1 in Nepal to test needs-based and participatory agricultural planning models, none of them were specifically concerned with the gender question, i.e. how to ensure that both women's and men's voices will be heard and their needs taken into equal account in planning processes. The project differed from the others not so much in the way that the participatory process was set up (they were all based on similar bottom-up and participatory planning models) but in how the project introduced specific measures to ensure the full participation of women in activities.

This case study describes the tools and methods that were used to meet the goal of the project for gender-sensitive and participatory planning. It also discusses the difficulties encountered along the way and how they were dealt with. Some of these difficulties were logistical since time was a constraint. Others stemmed from the strong cultural tradition in Nepal that gives men the dominant role in decision-making and hampered the project's objective of assuring women a voice. Other problems arose from differences in opinion among project staff and national counterparts on the meaning of participation, which resulted in a breakdown of communication and a lack of willingness to cooperate.

Needless to say, these challenges provided a great learning experience to all involved. The main purpose of this case study is, therefore, to share what was learned from this experience in the hope that others can learn from the project's successes as well as errors.

AS WELL AS BEING HOME to the highest mountains on earth, the Himalayas, Nepal has a wealth of diversity in its peoples, climate and natural resources. Its mountainous topography, however, means that much of rural Nepal remains isolated owing to a lack of roads and markets. The difficult access to much of the country's rural areas has hampered effective and sustainable development efforts. Agricultural productivity is low, with arable land increasingly fragmented and declining in fertility. Endemic rural poverty and food insecurity are critical issues, especially among tribal pople living in isolated rural areas. Extension contact in such areas is very limited.

Another crucial problem is overpopulation; Nepal's population is currently estimated at around 19 million (World Development Report, 1995). The impact of high rates of population growth can easily be seen in rural areas as forests are rapidly converted to cultivation, and many local areas have lost all of their forest reserves, private forests and common land in the last generation. Nepal's unique ecosystems include many endangered species of flora and fauna and valuable natural resources, all of which are fragile and vulnerable to degradation and rapid loss.

The Government of Nepal has attempted to address the problems of the rural population. Over the last four decades, a major share of national budgets has been spent on research and extension services for increasing the production and productivity of agricultural commodities. However, productivity levels continue to decrease, the ratio and number of people below the subsistence level are increasing, and the overall national gross domestic product (GDP) per caput has been stagnant or decreasing for decades.

More than 80 percent of the economically active population are engaged in agriculture which accounts for some 55 percent of GDP, in contrast to the 5 percent accounted for by manufacturing Owing to population growth, foodstuffs - which used to be exported - must now be imported. Foreign exchange earnings are small and depend largely on foreign assistance and loans, exports of a few agricultural products and some handicrafts (such as carpets and garments), as well as tourism. The average annual GDP growth rate was around 4 percent over the last two decades; but, since population grew at 2.6 percent or more during most of this period, there has been growth of only 1.4 percent in per caput GDP per annum (World Development Report, 1995).

Nepal is one of the world's poorest countries with a per caput GDP of about US$190. Data suggest that about 40 percent of the population live below the poverty line, which is even lower than the accepted international definition of absolute poverty; US$150 per caput per annum (World Development Report, 1995).

Since 1991, a strong economic liberalization programme has been in place under the guidance of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. There have been tariff cuts, the import license auction has been abolished, export incentives have improved, the dual exchange rate has been unified, foreign investment has been deregulated, and the tax system is being reformed to raise additional revenue and make it more efficient and equitable. The programme has had a positive impact on trade, improving the balance of payments and reducing inflation, but so far it has not had a noticeable effect on GDP growth.

Although rural life is hard for both men and women in Nepal, rural women work longer hours and have a greater workload than men owing to their double responsibility for reproductive and productive tasks. Women play a significant, if not predominant, role in agricultural production. Based on the data gathered during the PRAs carried out under the project, women in the high mountain areas were found to do more agricultural work than men, equal or more work in the middle hills and slightly less work in the Terai (low foothills and plains). In all agro-ecological zones, men generally perform tasks that require heavy physical labour such as ploughing (although women all over rural Nepal can be seen carrying heavy loads of fuelwood, water and fodder). Women, on the other hand, chiefly perform tedious and time-consuming work such as weeding, harvesting, threshing and milling. Especially in upland locations, women have a significant role in farm decision-making.

Although women's labour inputs to agriculture are often greater than men's, they rarely have access to extension services, institutional credit or production inputs. Extension agents direct most of their efforts to male farmers. Consequently, women farmers' food production is often insufficient and the productivity of their labour remains low.

In view of agriculture's important role in Nepal's development, the sector has been accorded high priority in almost all the development plans adopted since 1956. The Eighth Plan (1992-1997), which was the first plan formulated after the restoration of democracy in 1990, emphasized diversification and commercialization of the sector to raise farmers' income and employment opportunities. The plan included some specific objectives for agricultural development: increase of agricultural production and productivity to meet the growing domestic food demand and to provide raw materials for agro-based industries; increase of productive employment opportunities open to the majority of small and marginal farmers; and balancing of agricultural development and environmental protection. The three national development objectives of the plan were to: attain sustainable economic growth; alleviate poverty; and decrease regional imbalances.

His Majesty's Government of Nepal has just finished preparing a long-term Agriculture Perspective Plan (APP) for the next 20-year period (with the support of the Asian Development Bank, Manila and other multilateral and bilateral donor agencies, including the World Bank and FAO). The plan aims at increasing the per caput agricultural and non-agricultural growth rates by 2 and 3 percent per annum, respectively. To accelerate agricultural growth, the plan will concentrate on: four priority inputs - irrigation, roads and power, fertilizer, and technology; and four priority outputs - livestock, high-value crops, agribusiness and forestry. Following government approval of the APP, a task force is now working to develop an implementation strategy.

Women's important role and contribution to agriculture remained nearly invisible to policy- and decision-makers in Nepal before the restoration of democracy in 1990. The Eighth Plan introduced the first efforts by stating that "The Government is committed to equal and meaningful participation of women in development". One of the requirements of the Eighth Plan was to establish a Women Farmers' Development Division (WFDD) in the Ministry of Agriculture (MOA). WFDD's mandate is to mainstream gender issues in all agricultural policies and programmes and to increase the participation of women farmers in MOA activities and programmes. The Division has recently played a major role in ensuring that the APP recognizes women farmers' needs. Specifically, the APP aims at:

To achieve these objectives, the APP has suggested the following actions:

These policy commitments should also carry over into the upcoming Ninth Plan which will incorporate many of the strategies outlined in the APP.

ALTHOUGH MUCH WORK HAS BEEN done to integrate concern for the specific problems of women farmers into recent agricultural and development plans, agricultural sector planners and extension personnel still rarely take rural women's needs into consideration. This means that agricultural training and services do not reach women, and this has serious repercussions for food security and agricultural development. In many cases, planners lack information about the important roles that women play in agricultural production and household food security. But more often than not, they don't know how to learn from women farmers about their activities nor how to respond to their needs. To address this problem, FAO designed the project Improving Information on Women's Contribution to Agricultural Production for Gender-Sensitive Planning and launched it in three pilot countries, Namibia, the United Republic of Tanzania and Nepal. The aim of the project was to improve information on the situation of rural women and men and to involve them in local processes of planning in the agricultural sector.

Participation was a key component of these projects, in terms both of involving rural people in information collection and planning processes and of training the people who are responsible for the planning and delivery of agricultural services to work in a participatory manner with women as well as men farmers.

The specific task of the project in Nepal was to test and refine a participatory methodology that would incorporate gender concerns into agricultural planning from the grassroots to the district level. Its main objective was to strengthen the capacity of MOA to promote, support and monitor gender-sensitive planning at the district level in order to improve knowledge of the type of training and support services required by rural women.

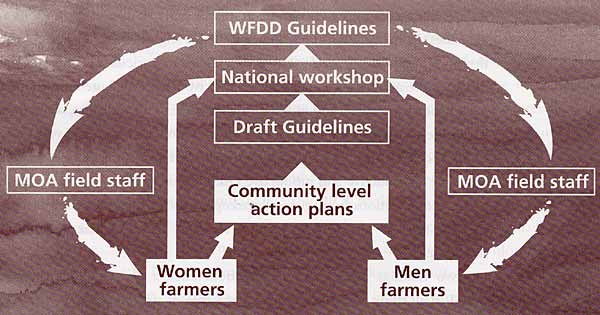

The main thrust of the project was to involve men and women farmers in select communities in each of Nepal's three distinct agro-ecological zones, together with district-level planners and agricultural outreach staff, in a gender-sensitive planning exercise. This would start with training district-level staff in a combination of gender analysis and PRA tools to learn how to identify both women and men farmers' needs. Trainees would then be given practical experience of carrying out gender-sensitive PRAs in designated villages in order to work with villagers to develop CAPs. Following the PRAs, district-level planning workshops would provide an opportunity for participants to present their findings and discuss their CAPs with district-level planners. Based on the experience of these planning exercises in the three pilot districts, WFDD - FAO's main counterpart on the project - would develop guidelines for gender-sensitive planning at the district level. The project would end with a national-level workshop to discuss the guidelines with high-level policy-makers and MOA staff in order to encourage their adoption into the overall planning processes of the Ministry.

Although the official starting date of the project was January 1996, it took almost six months for FAO and WFDD to look for and agree upon a suitable candidate2 for the lead gender consultant who would be responsible for managing and leading the project activities. This meant that the project did not get under way until June 1996. Given that the total time frame for the project was only 18 months, this delay meant a crucial loss of time and had consequences later on.

One of the first actions was to set up the central steering committee. As foreseen in the project document, this was mainly composed of MOA staff - including the Secretary of Agriculture - and chaired by the Chief of WFDD, who was also the National Project Director. The first meeting was held in June to explain the project's objectives, implementation strategy and work plan to members and to select the pilot districts for the PRAs. FAO thought that it would strengthen the project to conduct pilot activities in districts where there was already a FAO project in operation with which the new project could collaborate. On the basis of this criterion, and because they each represented one of Nepal's three agro-ecological zones3, the three districts chosen were: Nawalparasi in the Terai, where the Special Programme for Food Security in Nepal project (SPIN) was already operating; Sindhuli in the middle hills, where FAO's Enhancing the Agricultural Productivity of Rural Women project was operating; and Rasuwa in the high mountains, where the FARM project was operating.

The first field visits were made by the lead gender consultant to the pilot districts, as soon as the monsoon was over in September, to set up district steering committees (DSCs). These were to provide district-level collaboration and support among the various MOA offices and other line agencies that had crucial roles in project activities. The first DSC meetings were held to brief the members on the project and to select the village development committees where the gender-sensitive PRAs would take place. The criteria for selecting the actual study sites were: geographic location within the district, ethnicity, accessibility, level of development intervention, and economic well-being of the community.

Several sensitization efforts also took place in this period, the most important of which was a one-day consultative meeting held in November at the MOA offices in Kathmandu. The Secretary of Agriculture had requested this meeting to brief key policy-level staff at MOA on the project and to seek their cooperation for implementation and application of the guidelines which were to be one of the project's outputs. All the participants agreed on the importance of the project. However, an important question was raised about whether WFDD was the appropriate MOA counterpart for the project since WFDD plays more of an advocacy role within the Ministry. Many MOA staff felt that the project would have been better placed at the operational level to promote the integration of gender issues within the Department of Agriculture and Livestock which has stronger regional- and district-level ties through its agricultural offices.

In November, a PRA specialist joined the project team, and planning of the participatory planning exercises began in earnest. The project team, together with WFDD subject matter specialists, made a second visit to the districts. They held meetings with district officials to decide who should participate in the training and form the local PRA teams. The project team visited the development committees of those villages where PRAs were to take place to talk to the communities about the project and investigate their level of interest. They also visited relevant FAO project sites in the districts and talked with staff and beneficiaries about the planning and implementation of project activities.

Following this, the PRA specialist started to develop the training approach and prepare the materials. He adapted gender analysis and PRA materials that had been developed by the Women in Development Service (SDWW) at FAO to produce a training manual that suited the project's purposes.

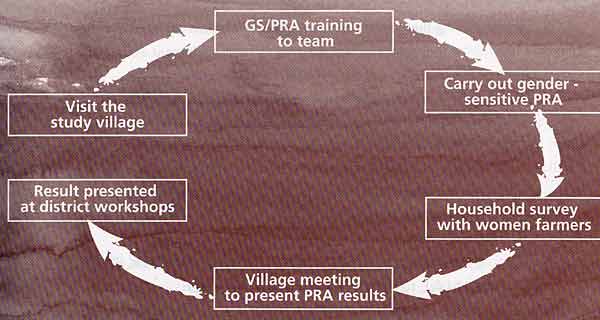

The PRA process itself is best seen in the figure on the facing page which maps out the various steps.

The project team held a short orientation training session (of three to four days) on gender analysis and PRA to familiarize trainees with gender analysis concepts and selected PRA tools. Participants included district agriculture and livestock officers and junior technicians as well as field staff from other relevant line agencies such as the Agricultural Development Bank of Nepal, the District Development Committee and the Ministry of Local Development. Later, these trainees were included in the PRA teams to give them the opportunity of practising the PRA tools they had just learned about.

From January until April of 1996, the PRA teams - now including the new trainees from each district -carried out gender-sensitive participatory planning exercises using PRA techniques in eight committees in the three pilot districts.

Specifically, the PRAs collected information that would help to:

The ultimate purpose of the PRAs, however, was to work with the communities to prepare CAPs which would be discussed with planners in the district-level workshops.

The PRAs also offered MOA and other relevant field-based staff the opportunity to see how useful gender analysis and PRA techniques are when gender-disaggregated information is being collected at the community level. It was hoped that this experience would enable staff to carry out similar gender-sensitive PRA exercises in their future work and help them to understand how they could make agricultural planning more gender-responsive. Another expectation was that the PRAs would make it easier for farmers to share and analyse their knowledge and experiences about farming, rural life and local development problems and opportunities with the district-based agricultural staff participating in the project.

In addition to the PRAs, 20 women farmers in each study site were interviewed individually using a set of formal questions (household survey). These structured interviews were carried out to:

In Nawalparasi, both men and women were interviewed. However, at the request of the national project director, only women farmers were interviewed in the other two districts, Sindhuli and Rasuwa, and thus the data collected from the household surveys reflect the views of women farmers only.

Steps in the PRA process |

|

By the end of April 1997, the gender-sensitive participatory planning exercises had been completed in the eight localities. The project team went back to Kathmandu to write up the PRA findings and prepare for the district-level workshops. Although the PRAs had gone very well, in spite of the pressures of a very tight schedule, the national project director was concerned that there would not be time to finish the project in time (by the end of June, according to the original schedule). She therefore decided to cancel the district-level workshops and concentrate on preparing the Guidelines for Gender-Sensitive District-Level Agricultural Planning and the national workshop.

Most of the project team believed that the district workshops were the most important step in the process, since they would have provided an opportunity to present the PRA findings to district officials, discuss the CAPs with them and, maybe, even get a commitment for action. Everyone who had participated on the project was, therefore, very frustrated by the national project director's decision. Moreover, the team knew that the farmers who had participated in the PRAs would be very disappointed and feel that the team had broken a promise to them.

An international consultant and a technical backstopping officer from FAO's SDWW Service in Rome arrived in June. The objective of their visit was to investigate the difficulties that had emerged, from both points of view. The visit helped to restore communications with the WFDD national project director so that decisions could be made about how to finalize important project outputs. A team from WFDD began work on a draft of the guidelines for gender-sensitive district-level agricultural planning so that they could be presented and discussed at the national workshop.

The project produced the following training and sensitization material:

The project's last official activity was the national workshop which provided a forum for discussion of how to translate Nepal's favourable policy on women in agriculture into action. WFDD mobilized high-level participation in the workshop - the Minister and other high-ranking officials opened it and more than 100 upper-level MOA managerial and technical staff, as well as district staff from the project sites, attended. Later, during the working group sessions, it became clear that MOA staff have been grappling with the question of how to address gender issues in their work. However, a relevant point raised during the final plenary was that, although there is sufficient recognition of the "who" (i.e. women as well as men farmers) and the "what" (gender-sensitive, needs-based planning), a problem remains as to the "how", i.e. how can mechanisms and procedures within MOA operations be changed to ensure that gender issues are fully addressed in agricultural planning processes and participatory approaches are adopted?

Separating "community" into men's and women's groups. The primary focus of the project was to gather information about needs at the very bottom of the planning ladder and take that information up to the district level, where planners could respond to it. What made this model different from other needs-based planning models was the attention given to ensuring that women had a voice in the planning process. For this reason, the "community" was divided into separate men's and women's groups in order to create a space where women could both participate in the exercise and express themselves freely. This focus on separate groups of men and women farmers within each community was a key entry point within the framework of a bottom-up planning process.

Training planners and extensionist in two-way communication. Another entry point was at the level of the district outreach staff and planners who were trained in the gender analysis and PRA techniques and who subsequently participated in the participatory needs assessments and planning exercises. Training this group and getting them to work in a participatory manner with the communities was the key to creating a process of two-way communication with information from the farmers flowing up the planning ladder and a response from outreach staff and planners coming back down.

Strengthening the women's unit. Yet another entry point involved the decision to locate the project at the central level with WFDD, rather than in a planning or extension division of MOA. This choice was made to strengthen the Division's capacity to use gender-sensitive and participatory approaches. WFDD was also able to provide support to the project from the policy level . For this reason, the Division was keen to have guidelines which would complement the project's fieldwork from the opposite direction - i.e. from the policy level down to the field - by explaining to field staff why participatory and gender-sensitive agricultural planning was important and guiding them on how to do it.

Making a bottom-up, gender-sensitive planning model work in a top-down, gender-blind world. This was the project's greatest challenge. The success of the experiment very much depended on whether those who held the decision-making power were open to and, better yet, committed to the participatory process. At the community level, despite all the measures to ensure that women participated fully in the planning exercises, men in the community have the final say on decisions, so many of the women's needs were not reflected adequately in the CAPs. (This problem is discussed in greater depth in the next section.)

At the district level, once staff were involved in the process they became enthusiastic practitioners. But, regardless of how committed they were, they still had to deal with MOA's top-down administration in which policy directives from the top, with limited financial resources, had to be matched with needs that emerged from the bottom.

At the central level, the project had strong support from many key players from within MOA. However, differences of opinion and friction arose between the project team and FAO, on one side, and WFDD managers, on the other, about how to support the participatory process and, in particular, about the importance of holding the district workshops. While junior WFDD staff, who took part in the training and PRAs, learned a great deal about how to undertake and support participatory planning processes, some upper-level decision-makers, who were overseeing events from Kathmandu, did not. The subsequent breakdown of communications over issues hampered the success of the project.

One of the most important lessons learned from the Nepal project is the need to establish mechanisms within the project framework for participatory decision-making, especially at the project management level. Such mechanisms are crucial in participatory projects so that information about what the project is doing can be shared with key decision-makers both to win their support and guidance and to ensure that decision-making power is divided among several key players who can convince the sceptical. In this project, the steering committee could have been used more effectively to discuss differences of opinion and handle problems that arose during project implementation.

The project used a combination of gender analysis and PRA techniques to learn about and document gender issues in agriculture and to facilitate the participation of rural women and men in needs-based agricultural planning. The specific PRA tools used and their purpose are outlined in the table below.

PRA tools used |

|

TOOL(S) |

PURPOSE(S) |

Social and resource mapping |

Indicate spatial distribution of roads, forests, water resources, institutions and organizations. Identify number of households, their ethnic composition and other socio-economic characteristics/variables. |

Seasonal calendars |

Assess women's and men's workloads by season. Learn about cropping patterns, farming systems, gender division of labour, food scarcity, climatic conditions, etc. |

Economic well-being ranking |

Understand local people's wealth criteria. Identify relative wealth and the different socio-economic characteristics of households and classes. |

Daily activity schedules |

Identify daily patterns of activity based on gender division of labour on an hourly basis and understand how busy women and men are throughout the day, how long they work, and when they have spare time for social and development activities. |

Resources analyses |

Indicate access to and control over private, community and public resources by gender. |

Mobility mapping |

Understand gender equities/inequities in terms of men's and women's contact with the outside world. Plot the frequency, distance and purposes of mobility. |

Decision-making matrix |

Understand decision-making on farming practices by gender. |

Venn diagrams |

Identify key actors and establish their relationships with village and local people. |

Pair-wise ranking |

Identify and prioritize problems experienced by men and women. |

CAP |

Assess the extent to which women's voices are respected when men and women sit together to identify solutions to the problems prioritized by the latter. Understand development alternatives and options, and give opportunity to men and women to learn from each other's experiences and knowledge. |

The gender analysis and PRA methods that the project used had strengths and weaknesses. On the potive side: the gender analysis and PRA approach helped trainees to understand gender dynamics in the communities; PRA helped the extensionists to build a better relationship with the community and vice versa; and the entire exercise generated reliable and detailed information. On the negative side: in spite of all the measures taken to ensure women's participation, their needs were not fully reflected in the CAPs; and the PRAs also raised high expectations, which were sometimes disappointed.

Gender, the new subject matter. Learning about gender analysis was an important event for the field staff, most of whom were unfamiliar with the basic concepts. Many had misconceptions about gender as a variable in the development process and the training helped to clarify these. What fascinated field staff the most was the revelation that gender was connected to the concept of power. After the gender training, participants became much more aware and alert to issues of power at the household and community levels. By combining gender analysis with the PRA experience, trainees really understood the importance and necessity of targeting extension and other development assistance according to "who does what".

Learning from each other and building relationships with local communities. One of the most important things that the trainees learned from carrying out the PRAs is that development depends on a two-way process of communication between field staff and rural people. One of the great strengths of the PRA process was that it helped improve the relationship between extension staff and villagers. It did this by helping each to learn about the other's difficulties and perspectives. Extension staff learned what the villagers expected from them and how villagers rated their performance. Farmers learned the problems and constraints of the field staff and why they do not make more regular and frequent visits to them. The PRA led to friendships between villagers - both men and women - and village-based extension staff. The latter often promised villagers that they would visit them regularly and make all possible efforts to work with them in order to address their needs, problems and concerns.

Reliable and relevant information. A second strength of the gender analysis and PRA approach is that it generated reliable information that was relevant both to extension officers and to the community - the evidence for this is the interest that villagers displayed in the process. Every day, more people from each village participated, and sometimes the groups were almost too large to handle. This excellent level of participation meant that there the information was very well validated; it was particularly carefully scrutinized during the last sessions, when graphics were posted on walls. From the gender perspective, the gender analysis and PRA process provided an opportunity for both extension staff and the communities to gain a better understanding of women's perspectives on farming systems and of the need to involve women in household and community decision-making and resource control.

The difficulty of assuring women a voice. A central concern for the project was how to ensure that women participated fully in the needs assessments and planning exercises carried out in each community. The project team made an effort to create a space where women could participate by:

While these techniques did ensure that women participated fully in the PRAs, a problem still arose in the final exercise, when both the women's and the men's groups were brought together to review each other's problem identification matrices and agree on a CAP. Although in some communities the women spoke up for themselves, there is a strong cultural tradition for them to acquiesce always to men's decisions.

Over-ambitious expectations. A serious weakness of the process was that it raised people's expectations. Although the project team made repeated attempts to explain the purpose of the study and the fact that villagers could only expect to participate in the district-level workshops, they continued to see the activities as preparation for "a big project" to come in the future.

This was why the district-level workshops would have been so constructive. They were designed as the project's way of responding to people's problems. The Nepalese Government's Decentralization Policy vested the district authorities with responsibility for the planning and implementation of development programmes. District-level workshops, by sharing the PRA information with these "powers that be", would have served two purposes: they would have raised awareness among decision-makers of the connection between women's role in farming systems and the need to integrate gender concerns into agricultural planning; and they would have given rural people, men and women, the opportunity of discussing their problems with decision-makers. It had been hoped that, as a result of the workshops, the district authorities would have made a commitment to address problems raised in the CAPs by, for example, providing more regular extension visits or training. Participants and the project team were seriously frustrated by the cancelling of the workshops, which also resulted in the PRAs becoming a merely extractive exercise rather than an integral part of bottom-up planning, as had originally been envisioned.

Lessons learned: tools and methods |

|

The most important factor in encouraging women to participate in PRA exercises was conducting the PRAs at times during the day when women were relatively free. Dividing the participants into separate male and female groups created a space where women could talk and participate, unhindered by the presence of men. Facilitators of the PRA process may need to intervene more strongly to ensure that women's voices are not completely overridden by men's when a consensus is being reached on community priorities. Facilitators need to learn to listen to women, handle male dominance in discussions and create the opportunities for women to both participate and speak out. |

One short PRA in a village is not enough to bring about a fundamental change in society's views of women's roles and status within the community. A longer-term process of working in each community is needed to sensitize men to women's situation and to empower women so that they can demand their fair share of development benefits. The PRA process should include some sort of follow-up to respond to the problems highlighted by its findings. The district workshops wold have been the most important step in the PRA process in Nepal because they would have provided an important opportunity to initiate action and influence the planning cycle. Cancelling these meetings broke a promise made to the participants who expected something concrete from the process, given the time and effort they had put into it. |

The main objective of the project was to strengthen MOA's institutional capacity so that it could address the needs of rural women in development planning more effectively. This was to be accomplished by training select district-level staff in the three pilot districts in gender analysis and PRA and then letting them try out bottom-up planning exercises. Three groups of MOA personnel, who would be key actors in the participatory planning process, would have benefited from the vertical capacity building component of the project:

Lack of time for training. A problem encountered in the capacity building component of the project was lack of time for proper training. As the project was behind schedule, owing to long delays in hiring project consultants, there was only time to provide a short orientation training (conducted by the PRA specialist, the lead gender consultant and the gender consultant) with selected district-level field staff before the PRAs were carried out in the communities in each district. This meant that training in gender analysis concepts and PRA tools was rushed through in four days. The subject matter and participatory tools were new to most trainees, and they needed more time to grasp the concepts and, even more importantly, practise using the tools. The problem was compounded by wide differences in educational levels, experience, job responsibilities and positions among the trainees.

Much of the learning had to take place in the field, during the PRAs. This turned out to be beneficial from a pedagogical point of view (trainees probably learned more easily by actually doing), but it meant that the project team had to take a stronger lead in facilitating the PRAs to ensure that the information generated was of good quality and that it fully reflected gender-based differences in activities, access to resources and perceptions of needs.

The easiest part of the gender analysis and PRA training was teaching the tools and methods. The more difficult aspect was convincing trainees to adjust their own attitudes and behaviour to support a truly participatory process with farmers. Acquiring all these skills takes time, lots of practice and feedback from others.

The importance of who to train. Altogether, 53 district-level staff participated in the gender analysis and PRA training. This included 23 field officials in Nawalparasi district and 15 each in Sindhuli and Rasuwa districts. Unfortunately, WFDD staff from the central level were very busy preparing inputs for the Ninth Development Plan at the same time as the training was taking place in the three districts, so only a few WFDD subject matter specialists were able to attend the training courses and take part in the subsequent PRAs.4

It had been planned that MOA district officers would take lead roles in facilitating PRA in the field, with backup from PRA consultants, but this did not happen. Because of their heavy workloads and other regular tasks, the district officers sent junior field staff to participate in the training and PRA field activities and, although this grassroots-level staff is now enthusiastic about using the approaches, it is unlikely that they will be able to apply what they have learned to facilitate gender-sensitive planning without the firm backing of their supervisors. This underlines the need for more sensitization and training at various levels (intermediate and policy) in order to gain decision-makers' support for bottom-up, participatory and gender-sensitive processes.

In spite of these drawbacks, it was obvious that trainees learned a great deal from the experience, as was discussed in the previous section.

The PRA was a learning process for all. Two other groups benefited from the project learning process: the main project consultants - the lead gender consultant and the PRA specialist; and the farmers who participated in the PRA. Neither of the two main project consultants (both men) were gender experts, but they had good management and PRA skills and dedicated themselves to acquiring the knowledge and skills needed to meet their terms of reference effectively. Needless to say, this self-guided learning experience was very enriching. Moreover, the PRA specialist, who was soon to go back to a key position in MOA's Monitoring and Evaluation Division, is committed to applying what he has learned to his new position.

More than 500 women and men farmers participated in the gender analysis and PRA needs identification and planning exercises. The PRA showed the villagers what resources they have, both natural and human, and brought their own problems to light in a constructive way. Most important, villagers learned that it was up to them to make the development process work in their village. Although there was no formal evaluation of the experience, several farmers expressed their appreciation of the conflict resolution skills they had learned during the PRA when solving problems among themselves. They said that they would continue to use the problem identification matrix and the prioritization exercises to come to a consensus over community problems.

The PRAs gave women participants a growing sense of self-confidence. The project teams observed that, as the PRAs progressed over the week they spent with each village, even those shy women who could hardly utter their names in a group on the first day began to speak and put their views and opinions boldly and effectively. The women's ability to express their views and needs was greatly helped by simply giving them an equal voice in the process and equal opportunity to use the PRA tools. Women were also able to demonstrate that they were just as good at using the tools as men. For example, women made beautiful social resource maps by using colourful food items and household products (e.g. maize kernels, different coloured grains and flours, vegetables, forest products and grasses) to represent village resources. During several of the PRAs, at the point when villagers came together to compare their resource maps, the men asked the women to give them some of these colourful items to liven up their duller compositions. The men's desire to imitate their efforts made the women proud of their own accomplishments. The men also realized that women have access to all of those varied products because of the complex range of food production and processing activities that they undertake.

Lessons learned: capacity building |

|

One short training course followed by one round of practice in the field were not enough for the trainees to acquire well-grounded skills in gender analysis, PRA and participatory planning. They needed more time to learn by doing, especially since the hardest skill for somebody new to participatory methods to acquire is how to adjust his or her attitudes and behaviour to support a truly participatory process with farmers. |

Staff in key decision-making positions needed to be involved in the training (or in other project activities) so that they could gain familiarity with the approaches and support their grassroots-level staff in applying what they had learned. Although projects may have a very bottom-up and grassroots orientation, they should recognize the need to involve stakeholders and decision-makers at all relevant levels to create a more conducive environment for success at the grassroots level. |

The PRAs generated a wealth of detailed information on men's and women's different activities, access to resources, mobility, perception of institutions and priorities. In many ways, the findings from the eight PRAs verified much of the prior research on gender-based differences in agriculture. They certainly validated the generally accepted notion that women contribute significantly to agricultural production and reflected the fact that, in upland areas, women tend to be the primary farmers. In all the study areas, rural women work longer hours and have greater workloads than men owing to their double responsibility for reproductive and productive tasks. However, there were enough surprises and deviations from generally accepted patterns to underline the point that site-specific variations in gender roles and priorities make assumptions hazardous.

Two findings deserve special mention. First, a glaring discrepancy was found in all study areas between women's role in agriculture and their access to extension services. The household surveys revealed that women often don't even know when an extension agent has visited the village; nobody -women, men or extension agents - seems to think that such an event concerns women.

The other important finding concerned women's priorities. In all the study areas, women consistently gave very high priority to access to education and training, which they see as the first step in improving their lives. It was apparent to the researchers that women were hesitant to participate in decision-making processes primarily because of their lack of education. They understand that they lag behind men in terms of access to and control over resources owing to their poor educational levels.

One implication of the PRA findings is clear; more extension and training should reach women. Given women's poor mobility, few can go to service and training centres for training and advice, so local solutions must be found. Agricultural skills training should include functional literacy programmes which would enable women farmers to develop reading, writing, maths, speaking, listening, interpersonal and problem-solving skills while acquiring knowledge about agricultural matters.

Figure 2 illustrates how the information generated by the PRAs was used; WFDD proposed to use the PRA information and the project experience as the basis for Guidelines for Gender-Sensitive District-Level Agricultural Planning, which are intended to help district-level staff understand how they can incorporate gender. Yet again, cancelling the district-level workshops significantly changed the course of the project by eliminating the mechanism for bringing information from the communities up the planning ladder to the district level. The actual information flow of the project differed significantly from the bottom-up, participatory "from farmer to planner and back" model proposed in the project design.

Project Information Flow |

|

Linkages were perhaps the weakest aspect of the project. It would have been very useful to try to link the project activities with other ongoing participatory planning processes but, although this did occur to some extent, the tight schedule severely limited the opportunities for exploring how the project could create mutually reinforcing and complementary activities. Another cause of poor linkages was related to the location of the project within WFDD rather than the more operationally oriented Divisions of Planning and Extension within MOA.

Linkages with the other FAO projects in each of the three districts were made at the district level. Some field-based staff from the FAO projects participated in the project training and the PRAs. The strongest linkages in this regard were made with the Enhancing the Agricultural Productivity of Rural Women project which was operating in Sinduli district. Staff from this project were fully involved in the gender-sensitive planning project activities, and it is hoped that the lessons they learned on how to support gender-sensitive and participatory planning will be applied to the next phase of their own project, which will put a greater focus on using participatory processes.

The central steering committee improved coordination among line agencies involved in the project and built support for activities (many committee members instructed field-level staff after the first meeting, resulting in good cooperation with the project team). But, the committee was not used very effectively for either information sharing, as a mechanism for participatory decision-making, or for dealing with the problems that arose.

One of the main lessons learned with regard to linkages is that it is better to build on existing coordination structures. For example, the District Steering Committees turned out to be counterproductive because they made district-level staff perceive the project as something outside their regular programme of work. It would have been more effective to build on existing coordination structures and planning mechanisms at the district level to promote a sense of ownership among district staff and to ensure greater integration of the project's approaches into normal, pre-existing planning procedures.

WFDD played a leading role in guiding the formulation of a more favourable policy environment in Nepal and raising awareness of the need to change mechanisms, procedures and attitudes in order to build a more enabling environment for gender-sensitive agricultural planning. However, for long-term institutionalization, the approaches tested under the project need to be adopted by MOA's technical divisions responsible for planning, outreach and training. Any future activities to introduce gender-sensitive and participatory approaches into MOA should, therefore, perhaps be led by the technical units, as was suggested at one of the first sensitization meetings held with MOA staff. This would create a greater sense of ownership at the operational level, where actions and decisions take place.

Another useful move would be to make training in gender analysis and participatory methods an integral part of pre- and in-service training programmes at MOA training institutes and at the Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science at Tribhuvan University.

On the basis of their experience with this project, the PRA specialist and the lead gender consultant recommend the following additional actions:

THIS PROJECT WAS AN EXPERIMENT. Its purpose was to find out how a participatory and gender-sensitive planning process could work in Nepal. The fieldwork was very fruitful and provided a learning experience for both rural people and agricultural outreach staff. But the project was not able to complete the information gathering-discussion-planning cycle it had envisioned. Based on this experience, the following advice can be given to others who are interested in supporting similar experiments:

1 These include a number of projects and programmes to support decentralized planning, monitoring and evaluation, and to strengthen the institutional capacity in this regard: the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) project Supporting Decentralization in Nepal - DAP (NEP/92/012) which is partially implemented by FAO; the German Agency for Technical Cooperation- (GTZ) supported Promotion of Livestock Breeding Project - PLBP (subtitled Development of a Decentralized Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation System on a National Basis); and the World Bank Extension Programme.

2 Although there are many qualified gender experts in Nepal, none were free to work for such a long period.

3 Geographically, Nepal has five regions: the High Himalayas, the High Mountains, the Middle Mountains, the Siwaliks (Inner Terai) and the Terai. However, it is also divided into three major agro-ecological regions: the mountains, the middle hills and the Terai. For administrative and development purposes, the country is divided into 75 districts. A district is further divided into several (40 to 70) village development committees, which are territorially based politico-administrative units governed by an elected council consisting of a chairperson, a vice chairperson and nine ward chairpersons elected from each of its nine wards. A ward is composed of one or more small villages or hamlets.

4 To make up for this, FAO proposed extending the project to include an additional week-long gender analysis training course for WFDD staff.