E. MHINA

Project Gender Analysis Trainer and National Researcher

|

THIS CASE STUDY DESCRIBES a project in the United Republic of Tanzania called Improving Information on Women's Contribution to Agricultural Production for Gender-Sensitive Planning. It presents the methodology used for training and for collecting information through gender-sensitive participatory diagnostic research on women in agriculture. The case study gives an overview of training in participatory rural appraisal (PRA) and gender analysis; describes the analysis applied to findings from the eight villages where practical exercises were performed; and outlines recommendations for conducting further activities in Tanzania. The project focused on planning, participation and gender. Planning and participation in the sense of actively involving rural women and men in participatory planning exercises (using PRA) to collect information about their agricultural development needs. Gender in the sense of ensuring that both men and women had a voice in the planning exercise and that both men's and women's needs were recognized. District-level planners and extension staff, who are in a position to respond to farmers' needs, also participated in the process.

As a pilot exercise, the project was mainly concerned with testing a model for participatory and gender-sensitive planning. Although many projects in Tanzania have focused on building the capacity of government and non-governmental staff to facilitate rural women's access to training, credit or other resources, none has been specifically concerned with the agricultural planning process.

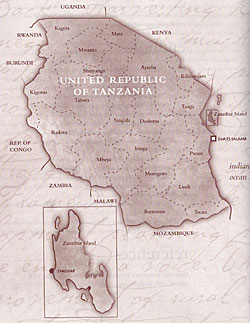

IN 1884, THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA BECAME a German colony, part of German East Africa. In 1920, the League of Nations made it a trusteeship under the United Kingdom. Julius Kambarage Nyerere became its first Prime Minister in 1961 and, in 1962, he became President and was the most influential leader under self rule. Zanzibar and Tanganyika were united in April 1964, to form the United Republic of Tanzania. The country is divided into 25 administrative regions (five in Zanzibar) and 94 administrative districts.

Tanzania has a surface area of 945 234 km2, 7 percent of which is water. In 1990, 4.7 million ha of land were used for cultivation and 46 million ha were under forestry cultivation. Of the 400 000 km2 of arable land, between 5 and 10 percent is permanently cultivated - 20 percent of the land is moderately suitable for agriculture. Shifting agriculture is the most frequently found method of farming. Some 50 percent of the land is used for grazing, and conflicts between pastoralists and cultivators are common. Forests and woodland make up 43 percent of the land area. In most households, 80 percent of energy requirements are supplied by fuelwood, which rural families spend 20 percent of their time collecting.

In a 1988 census, the population was 23.1 million, with an average growth rate of 2.8 percent, or 600 000 per year. By 2000, the country's population is expected to reach 33 million. In 1988, 80 percent of the population was living in rural areas, decreasing to 78 percent in 1992. Tanzania has more than 120 ethnic groups, mainly Bantu, plus significant Asian and Arab populations. Religious affiliations are divided equally between Christians and Moslems. Population density was 26 per square kilometre in 1988 and 30 per square kilometre in 1992.

The population is concentrated in the peripheral parts of the country. Women make up 51 percent of the population and 48 percent of the labour force. Women also constitute 85 percent of labour in agricultural production, 5 percent in industry and 6 percent in services. Women's contribution to industry increased by 2 percent between 1965 and 1990. The average life expectancy is 51.2 years. Infant mortality for children under five years (per 1 000 live births) was 141 in 1991 and declined to 88 in 1996.

The country has six agro-ecological zones: coastal areas with medium potential for agriculture; arid lands with poor soil fertility and tsetse infestations; semi-arid lands; plateaux with adequate rainfall and fertile soil; the Southern and Western Highlands; and the Northern Highlands with adequate rainfall and fertile soils. The highlands, located on the nation's periphery, account for less than 5 percent of total land surface but are home to 20 percent of the population and provide 30 percent of agricultural produce and 50 percent of total crop exports.

Less than half of the country receives more than 700 mm of annual rainfall. In such areas, agropastoralism predominates. Tsetse is found in 60 percent of the country. Surplus food production is becoming increasingly frequent in areas of higher altitudes and rainfall.

Before independence, United Kingdom rule encouraged settlers and large agricultural interests to develop estates and plantations, using forced labour (a source of nationalist discontent) and laws about minimum land areas for export crops. Large-farm production of tea, coffee and sisal gained momentum in the post-Second World War period, and emphasis was put on erosion control and conservation. At this time, peasant production was largely subsistence with minimal trade support from the government. Small-scale, indigenous production centred on the family and extended family. Only surplus produce was marketed. Customs and traditions determined land- or livestock ownership patterns and labour was divided by gender, age and skill. Although farming families were self-sufficient, the use of traditional or rudimentary technology and the small scale of production meant that they lived from day to day and from season to season.

Approximately 98 percent of the rural women classified as economically active are engaged in agriculture. Women farmers are also often casual labourers and unpaid family workers in both commercial and subsistence agriculture, including livestock and fishing.

Women have the main responsibility for both domestic work and subsistence agriculture, especially food crop production. Time-use studies consistently show that women spend more hours per day than men in both productive and reproductive activities. Traditionally, women are responsible for almost all the livestock activities in dairy husbandry (feeding, milking, milk processing, marketing, etc.). In crop production, men and women participate fairly equally in site clearance, land preparation, sowing and planting, while women handle most of the weeding, harvesting, transportation, processing and storage activities. Women are also responsible for food preparation, fetching water and gathering fuelwood (FAO, 1995).

Since the mid-1970s, Tanzania's agricultural policy has concentrated strongly on: pricing of food and cash crops (with non-official food crop prices competing with official cash crops prices); cooperatives, marketing boards and crop authorities (with statutory crop monopolies); agricultural industries; directives; state farms and ranches; and crop improvement programmes.

A new agricultural policy was inaugurated in January 1997 for four main reasons: the merger of agriculture and livestock policies; changes arising from economic policy transformation; initiation of a new land policy that advocates the changing of land-use patterns; and new emphasis on environmental management and protection.

Recognizing women farmers' needs in national agricultural policies. The 1983 Agriculture Policy ignored gender issues, especially women's rights with regard to landownership, access to credit and/or the labour situation. The policy made few visible efforts to integrate women's issues, although it did acknowledge that women's contribution to agricultural production was significant. This lack of concern for the problems facing women in agriculture occurred at a time when increasing numbers of women were looking for work on large farms, tea plantations and coffee estates because they could not subsist on their family farms' incomes alone. Some farming women preferred to sell their labour rather than work on their husbands' farms without monetary returns.

In 1985, a Women in Development (WID) Focal Point Unit was established in the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MAC). Its functions included: working with regional focal points and agencies involved with women in rural development issues; training rural women in agricultural credit matters and other entrepreneurial activities; and organizing seminars for women's groups at village level in collaboration with other like-minded institutions.

The unit also worked to ensure that national extension programmes benefited women and encouraged them to take leadership positions within agriculture. A Women and Youth Unit was established at the office of the Commissioner for Research and Farmers' Education in the Ministry of Agriculture in Zanzibar, with the aims of: encouraging women and young people to form groups and participate in agricultural, livestock, forestry and fishing activities; offering nutrition education to women; and working towards an equitable distribution of incomes and an improvement in the overall economic status of women and young people. Although the ministries had no clear policies and strategies for promoting women's advancement in agriculture, a few tangible successes were achieved.

In the 1997 Agricultural Policy, women's contribution to agriculture was recognized: "It is estimated that the ratio of males to females in the agricultural sector is 1:1.5. In Tanzania, women produce about 70 percent of the food crops and also bear substantial responsibilities for many aspects of export crops and livestock production. However, their access to productive resources (land, water, etc.) supportive services (marketing services, credit and labour-saving facilities, etc.) and income arising from agricultural production is severely limited by social and traditional factors."

The policy also acknowledges that social and traditional factors can prevent women from contributing effectively, and hints that social and legal actions taken by other ministries could reduce or minimize such limitations. It states that MAC will direct its extension, research, training and credit services to rural women to enable them to contribute effectively to agricultural production. Among strategies chosen to alleviate the situation are labour-saving technologies, cooperation among women, and support of women's participation in the planning and management of development programmes.

It also states that the Ministry should promote the access of women and youth to land, credit, education and information. Another direct reference to women states that extension services will be demand-driven and address the needs of livestock keepers, farmers and other beneficiaries with special attention given to women in recognition of their critical role in family household management and food production. It calls for initiating targeted messages and other innovative methods for reaching women and states that the Ministry, through extension service, will assist farm families (especially women and youth groups) to identify viable income-generating activities.

The policy specifies that training, credit, land and low-cost environmentally friendly technologies should be provided for women. It says that women will be entitled to acquire land in their own right not only through purchase but through allocation, and recognizes that women in the rural areas play a critical role in food production, transportation, processing and distribution.

ALTHOUGH MUCH WORK HAS BEEN done to integrate the specific problems of women farmers into agricultural policy and plans, agricultural sector planners and extension personnel rarely take rural women's needs into consideration. This means that agricultural training and services do not reach women, and this has serious repercussions for food security and agricultural development. In many cases, planners lack information about women's important roles in agricultural production and household food security but, more often than not, they do not know how to learn from women farmers about their activities or how to respond to their needs. To address this problem, FAO designed the Improving Information on Women's Contribution to Agricultural Production for Gender-Sensitive Planning project and launched it in three pilot countries - Namibia, Tanzania and Nepal. The aim of the project was to improve information on the situation of rural women and men and to involve them in local processes of planning in the agricultural sector.

Participation was a key component of this project, both in terms of involving rural people in information collection and planning processes and in terms of training those responsible for the planning and delivery of agricultural services to work in a participatory manner with women as well as men farmers.

The specific task of the project in Tanzania was to strengthen the institutional capacity of staff at the MACs on the mainland and in Zanzibar to learn from women farmers about their needs and to incorporate those needs into agricultural planning.

The main thrust of the project involved men and women farmers from select communities in three distinct agro-ecological zones of the country and included agricultural planners and government staff from district, regional and national levels in a gender-sensitive planning exercise. This started with training government staff in a combination of gender analysis and PRA tools to demonstrate how to identify both women and men farmers' needs. The trainees were then given practical experience in carrying out gender-sensitive PRAs in designated villages in order to work with the villagers to develop community action plans (CAPs). Following the PRAs, regional-level workshops provided an opportunity for government staff to present their findings to a broader audience.

The project ended with a national-level workshop to discuss experiences and findings with high-level policy-makers and Ministry staff and to develop a national action plan for gender-sensitive and participatory agricultural planning.

The project started in March 1995. As one of its first activities, a steering committee was established on 18 September 1995. It included members from the Planning Commission, the Ministries of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Tourism and Natural Resources, and Lands, Housing and Urban Development, and FAO. The Ministries of Community Development, and Women's Affairs and Children were not represented, nor was the Office of the Prime Minister. The National Coordinator from MAC on the mainland joined the project in October 1995, and the National Coordinator from Zanzibar joined in February 1996. The MAC's acting Commissioner of Planning served as the overall project coordinator. A PRA trainer and a gender analysis trainer were contracted.

The goal of both the training and the fieldwork was to analyse the actual situation of women and men in the specified villages. The PRA tools were chosen after a field trial at the FAO-assisted project Women in Irrigated Agriculture (GCP/URT/103/NET), conducted at Igurusi's Utengule-Usangu Basin in Mbeya.

The training consisted of five to eight days in the classroom to introduce the theoretical and methodological aspects of PRA and gender analysis, and eight to ten days in the field with practical exercises and application of the chosen tools in selected village communities. The location of the field exercise was selected jointly by regional and district staff. Village leaders and residents were responsible for selecting villages where the PRA clinic was to be concentrated. Field exercises included community meetings between villagers and the visiting PRA team, determination of the preferred location, wealth ranking and household interviews, focus group interviews, problem identification, and designing of CAPs.

The PRA process, and how it was reflected at regional and national levels, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Three training events (in Mbeya, Dodoma and Zanzibar North) and three field PRAs (in Ileje, Dodoma Rural and Zanzibar North) were held, at which a total of 49 government staff were trained, including 17 women. The objective of the training was to increase efficiency and gender responsiveness in rural development policies and programmes through identification, targeting and representation of women and men farmers, as well as increasing the knowledge and analysing the needs of beneficiaries.

Ministerial staff, policy-makers and planners in the agricultural and rural development sectors were trained in the value of gender analysis and participatory approaches for addressing the needs of rural women and in the mainstreaming of gender issues into agricultural and rural policies, planning and programme development. The training exercises aimed at integrating gender issues into the planning process, as well as the policies, programmes and projects of MAC.

Specifically, the information collected during the PRAs was used to:

The PRAs also showed participants the value of using gender analysis and PRA techniques to collect gender-disaggregated information at the community level. It was hoped that this experience would enable them to carry out similar gender-sensitive PRA exercises and help them to understand how to make agricultural planning more gender-responsive. It was also hoped that the PRAs would enhance farmers' capacities to share their knowledge about farming, rural life and local development problems and opportunities with the agricultural staff participating in the project.

Regional workshops. Three regional technical workshops were held to disseminate findings of the PRA and gender analysis research and fieldwork. Regional and district government staff, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and representatives from rural women's associations were invited.

The workshops provided a platform for discussion of the issues arising from the gender analysis and PRA research, and exchange of views on ways to make agricultural programmes and projects at the regional and district levels more responsive to rural women's needs and constraints. They also provided an opportunity to formulate recommendations on gender-sensitive changes in agricultural policies and programmes. The recommendations of the regional workshops were divided into three categories: research, data collection and dissemination methods; gender sensitization and training; and policy reform and coordination.

Research, data collection and dissemination |

|

Recommendations: |

|

compile case studies on the socio-cultural causes of gender imbalances in farming; create gender-disaggregated data banks which will enable policy-makers and planners to make resources available to farmers on the basis of gender roles and specific gender needs; establish appropriate data collection mechanisms that make effective use of multidisciplinary teams for data collection, through promoting PRA in combination with other research methodologies; study labour requirements for agricultural and household activities in order to create appropriate technological solutions; |

assess gender-specific differences in the utilization of traditional and modern agricultural technologies; encourage NGOs and community-based organizations to participate in the collection and dissemination of gender-disaggregated information using means that are accessible to participants (e.g. broadcast and print media) distribute documents to government officials (from village to national levels) on gender issues regarding agriculture and social issues; encourage the activities of cultural and drama groups that sensitize communities to the need for including gender in all levels of development planning and emphasize the consequences of neglecting gender concerns |

Gender sensitization and training |

Recommendations: |

make an inventory of experts in PRA and gender analysis who can train staff and community members at district and regional levels; prepare training modules for the in-service training of agricultural staff on using PRA methods in interdisciplinary teams to increase people's participation in the planning process; develop training packages on socio-economic and gender analysis, with emphasis on tools for identification, generation, analysis and presentation of gender-disaggregated information. |

Reforms and coordination measures |

|

Recommendations: |

|

refine agricultural policies in order to mainstream gender in the formulation and implementation of these policies; emphasize the goal of achieving food security at household level through addressing existing gender imbalances; encourage greater participation of women and men farmers in needs assessments during the formulation and implementation of projects and programmes; |

promote gender equity in the ownership and control of agricultural production resources by reviewing and revising all laws that discriminate on the basis of gender in order to mainstream gender concerns into agriculture and other related sectors; establish coordinating committees to encourage and supervise the mainstreaming of gender into agricultural plans and programmes. |

The project has produced the following training and sensitization material:

Gender training for senior ministry staff. Thirty-one senior staff members from the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Natural Resources in Zanzibar, including policy-makers and managers, attended gender planning methodology training in December 1996. Similar training was organized on the mainland in May 1997, for 20 senior staff from MAC.

The training brought together MAC staff members to sensitize them to the necessity of understanding the gender needs of farmers when allocating resources to the agricultural sector. This understanding was to be based on an analysis of different gender roles in farming systems. It was necessary to: develop a common understanding of gender analysis; provide information on the present gender status of selected MAC project activities; and introduce tools for the analysis of gender roles and needs in selected MAC project activities.

The national workshop. In July 1997, a national workshop was held at Dar es Salaam; it was opened by the Deputy Minister for Agriculture and Cooperatives. Its main purpose was to prepare a National Action Plan for Gender-Sensitive Agricultural Planning and Programmes by outlining actions to be taken up to and beyond the year 2000.

After a presentation of the PRA and research findings, participants were divided into four working groups: Zanzibar and mainland NGOs; Zanzibar agricultural staff; mainland agricultural staff; and Zanzibar and mainland government staff. The groups were asked to prepare guidelines for integrating gender-sensitive planning into their respective activities. Discussions led to the identification of overall goals, objectives, strategies, actions, responsible agents/institutions and the time frame for achieving the planned measures. The following is a summary of the recommended measures:

Although this project was concerned with participatory planning, the entry point was at the ministerial level. From there, the project reached down to the regional and district levels. Village leaders and residents were usually only informed of the PRA fieldwork a couple of weeks before it was due to begin. Overall there was a feeling that, until a gender-responsive PRA approach becomes fully integrated and can be applied by local government staff, NGOs and other community-based rural planning and development institutions, outside intervention will be needed to introduce a participatory process.

This has implications at all levels. At the policy level, there is a need to initiate capacity building and to provide resources. At the farmer level, for field implementation, various tools for the collection of information, analysis and utilization need to be introduced. Government staff still play a key role in organizing and supervising development work from village to national level and the government's advocacy of change is needed, because farmers will often not adopt changes unless they are strongly supported by the government.

One purpose of the participatory planning process was to ensure that women had a voice in the planning process. For this reason, the community was divided into men's and women's focus groups to create an environment in which women could both participate in the exercise and express themselves freely. This focus on separate groups of men and women farmers within each community was a key entry point within the framework of a bottom-up planning process.

Lessons learned: entry point |

|

When introducing a participatory process, outside intervention is needed until gender-responsive PRA has become fully integrated and is being applied by local governments, NGOs and community-based institutions dealing with rural planning and development. |

Farmers will not adopt most changes unless they are supported by the government, so governmental advocacy of change is needed. Separate focus groups are needed for men and women, to give women the opportunity to participate and express themselves freely. |

The project used a combination of gender analysis and PRA techniques to learn about and document gender issues in agriculture and to facilitate the participation of rural women and men in needs-based agricultural planning. The specific PRA tools used and their purpose(s) are found in the following table.

PRA tools and purposes |

|

Tool |

Purpose(s) |

Community resource maps |

Indicate spatial distribution of roads, forests, water resources, institutions and organizations Identify number of households, their ethnic composition and other socio-economic characteristics/variables |

Seasonal calendars |

Assess women's and men's seasonal workloads Indicate cropping patterns, farming systems, gender division of labour, food scarcity, climatic conditions, etc. |

Wealth ranking |

Illustrates local people's criteria of wealth Identifies relative wealth and the different socio-economic characteristics of households and classes |

Transect walks |

Help in organization and refinement of spatial information Summarize local conditions |

Gender resource maps |

Indicate access to and control over private, community and public resources by gender |

Historical profiles, time and trend lines |

Show the community's perceptions of change in local situation |

Decision-making matrices |

Illustrate decision-making on farming practices by gender |

Venn diagrams |

Identify key actors and establish the relationships between the village and local people |

Problem ranking |

Identifies and prioritizes the problems experienced by men and women |

Semi-structured interviews |

Probe key questions and follow-up topics raised by other tools |

Focus group interviews |

Probe key questions and follow-up topics raised by other tools |

Community action plans |

Assess the extent to which women's voices are respected when men and women work together to identify solutions for the problems prioritized by women Define development alternatives and options, and give men and women the opportunity to learn from each other's experiences and knowledge |

The gender analysis and PRA methods used by the project have both strengths and weaknesses. On the positive side, there is a high level of community participation and flexibility; on the negative side, even though there is a broad sampling with carefully considered selection, questions arise as to the statistical validity of data gleaned from such informal methods.

Community participation. PRA involves a high degree of community participation compared with other approaches. In addition to initial meetings with the whole village, selected households in all communities were engaged throughout the exercise and in all aspects of the study. The PRAs also raised people's self-awareness and encouraged them to suggest viable solutions to their problems. Practical solutions included constructing new wells, enforcing village bylaws on grazing by livestock, soliciting more land from underutilized state farms, and demanding affordable prices or packaging of inputs.

In addition, PRA facilitated the analysis of complex issues and problems, and solutions were provided by the community itself. Examples of complex problems were: the choice between using expensive artificial fertilizers or shifting to more affordable organic farmyard manure; whether to discipline corrupt health staff through dismissals, reprimands or other measures; and whether the government should or should not intervene on prices and the provision of agricultural inputs.

Gender analysis. The tools and methods used for gender analysis included: analysis of gender roles; analysis of access to and control of resources; assessment of whether gender needs were met or not; analysis of gender inequality; analysis of significance of the various causes of gender inequality; and the gender equality and empowerment framework which enabled most participants to visualize the different levels of gender equality and empowerment that various activities either facilitated or denied to women and some men.

Gender analysis was further integrated in the PRA fieldwork by ensuring that there were equal numbers of male and female key informers. However, most respondents in the in-depth household interviews were women, since they were more easy to reach in the households.

The experiences also proved that gender analysis is flexible. Its techniques and tools can be adapted and integrated into most other research approaches. Gender analysis not only indicates the social relationships between men and women and their eventual implications, it also exposes the constraints and opportunities for men and women in their respective development activities, i.e. the divisions of labour, time and access to formal credit facilities, training and skills and productive resources. Gender analysis could easily be integrated into such activities as: discussions in which male and female focus groups identify and prioritize their perceptions of problems, causes and solutions; gender resource mapping with gender-specific identification of who has control and access and who provides labour for different items on a farm; and creation of a gender-disaggregated seasonal activities calendar that provides information on who actually participates in what activity during which season.

Statisticians' concerns. PRA and gender analysis were the main methods used in the exercise. Some national-level professional staff members were concerned about the statistical validity of the findings and the consequences if these were to be translated into planning. The issues in question include random sampling, the shunning of formal structured questionnaires, inaccurate measurements of sizes and distances, the lack of an exhaustive statistical analysis, and the apparent trend of generalizing information drawn from a few villages.

In addition to PRA and gender analysis tools, household interviews and individual observations were used to collect information. However, the absence of a formal questionnaire or checklist created considerable difficulties in the subsequent organization of the information. Considering that the main objective of the exercise was to improve information on women's contribution, a checklist would certainly have made things much easier.

The sampling frame included heads of households with a distinction made between male- and female-headed households. Sampling was done through wealth ranking on the basis of socio-economic resources. This was followed by selection from three socio-economic resource categories - 10 percent from high, 30 percent from medium and 60 percent from low. This approach increased the statistical validity of the village samples.

Lessons learned: tools and methods |

|

PRA has a high degree of community participation. It raises people's self-awareness and encourages problem analysis and the search for solutions. The techniques and tools of gender analysis are flexible, which allows it to be adapted and used in many research and data collection efforts. |

The organization of information gathered through PRA and gender analysis would have been easier with a checklist. Using selection, according to socio-economic groups, in the sampling frame improves the statistical validity of the information gathered from the villages. |

The main objective of the project was to strengthen the capacity of staff members at the MACs on the mainland and in Zanzibar to learn from women farmers and to incorporate their needs in agricultural planning. This was to be accomplished by training select government staff in gender analysis and PRA. Government personnel at national, regional and district levels, who are key actors in the participatory planning process, benefited from the vertical capacity building component of the project. They participated in theoretical and practical training on gender analysis and PRA.

PRA as a learning process for all. More than 230 farmers participated in the gender analysis and PRA fieldwork. The farmers' reactions to the village-level problem analysis and solving varied, some recognizing its empowerment benefits in terms of taking control of their own lives and others trying to use the approach to demand control over the process. A third reaction was indifference to the participatory planning process. Farmers could express their opinions freely to district staff who were members of the field teams and to planners and policy-makers who were part of the teams or who visited the villages during presentation of CAPs at the end of the PRA.

Gender training. Senior-level decision-makers and planners from MAC participated in gender training. The objective was to sensitize them so that they could understand the gender-differentiated needs of farmers when allocating resources to the agricultural sector. This sensitization, which was based on an analysis of gender roles in various farming systems, would create support for gender-sensitive and participatory agricultural planning.

Information collection and dissemination. During the regional and national workshops, field findings were disseminated. Activities to improve the collection, analysis and dissemination of gender-disaggregated information were suggested and the emphasis was on the need for and use of gender-disaggregated data in agriculture. Because most data producers are oblivious to gender issues, there is a scarcity of gender-disaggregated data in almost all sectors (exceptions are health and education). During the workshops it was underlined that most producers of statistics are unaware of and insensitive to gender issues, because they have not received training in gender analysis. Representatives from NGOs, farming communities and regional government organizations discussed and proposed alternative arrangements for the better collection and dissemination of gender-disaggregated information.

Lessons learned: capacity building |

|

Not all farmers react in the same way to the idea of participatory planning and empowerment. Some are interested in having control over their own lives, others are anxious to control the participatory process, and others are indifferent. There is no village-level capacity to identify and analyse problems and plan activities that overcome the constraints. |

Training senior-level decision-makers to sensitize them to gender issues encourages them to support gender-sensitive and participatory agricultural planning. Most data producers are oblivious to gender issues. They need to be trained in gender analysis to encourage them to collect and use gender-disaggregated data. |

The PRAs generated a wealth of detailed information on men's and women's different activities, access to resources, mobility, perception of institutions and priorities. In many ways, the findings from the eight PRAs verified much of the research on gender-based differences in agriculture, e.g. that women are the main agricultural producers.

The information collected focused on disparities between women and men with regard to gender roles in agriculture, access to and control over resources, and the numerous unmet needs of women compared with men farmers.

One of these unmet needs is the glaring gap, which was found in all study areas, between the important role of women in agriculture and their limited access to extension services. The gender analysis PRA revealed that 80 percent of rural women have no contact with agricultural extension officers.

Another discrepancy was that, although nearly 80 percent of women are dependent on farming for their main income, women farmers face major constraints in access to agricultural inputs and resources. This was illustrated by the following findings.

In the PRA districts of the mainland, the percentage of female heads of households was high: in Mbeya it was 30 percent and in Dodoma 33 percent. This is much higher than the national average of 17.5 percent and indicates that national statistics probably use the de facto definition of female-headed household, while the PRA research used the de jure definition, which includes widows, single mothers, divorcees and separated women.

Women in Dodoma rural district seemed to perform nearly all of the main activities involved in production of the major food and cash crops. On average, 69 percent of women participated in all stages of agricultural production, while 25 percent of men did.

Women appeared to participate actively in decision-making on a range of issues. For example in Dodoma, women participated in decisions on types of crop to grow, where to plant, what techniques to use and how to distribute income from crop sales. Women also took part in: determining whether or not money should be borrowed; when livestock, poultry and surplus crops should be sold; and how to distribute income accrued from the sale of livestock. Most decisions were made jointly with men, although fewer men were involved in decisions on the distribution of income from livestock sales, whether money should be borrowed and the sale of surplus livestock.

Lessons learned: gender information |

There is a gap between the important role women play in agriculture and their limited access to extension services. Women farmers do not have sufficient access to agricultural inputs and resources. The PRA research indicated that the percentage of female-headed households was much higher than the national statistics indicated, probably because PRA research used a definition that includes widows, single mothers, divorcees and separated women. Women participate actively in decision-making on a range of issues and often, but not always, those decisions are made jointly with men. |

Links between farmers and planners. A strong link was established during the gender analysis and PRA fieldwork between women and men farmers, on the one hand, and agricultural planners and policy-makers, on the other. During the fieldwork, government staff met more than 200 farmers in a manner which was new to most of them. At the village level, farmers formulated CAPs which they presented to the government staff. These plans detailed problems identified and analysed by women and men farmers, but also contained actions for overcoming some of the identified problems. An important lesson learned by both village members and government staff was that there is the capacity at village level to identify and analyse problems and to plan activities that overcome them.

Cross-sectoral linkages. Many cross-sectoral linkages were established during the course of the project. Linkages were built among the MACs from the mainland and Zanzibar and other government agencies, including community development offices, district councils, the Central Bureau of Statistics, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, the Planning Commission and the Vice President's Office Directorate of Environment. Linkages were also established with various NGOs and research institutions, such as Sokoine University of Agriculture and the Institute of Development Studies.

Extension officers. Linkages are expected to be established by the extension officers. The new agricultural policy considers extension staff as a strong link among farmers, livestock keepers and research and aims at strengthening village extension officers' roles in the distribution of inputs, credit handling and the enforcement of by-laws. The policy also encourages the extension services to focus on supporting farm families, especially women's and youth groups, in establishing feasible income-generating activities.

Several aspects of the project, its methods and tools, led to the much-needed institutionalization of its approach.

Training government staff at various levels in such methods as gender analysis and PRA created an enabling environment for the mainstreaming of gender-responsive participatory approaches into agricultural development and planning.

An increased understanding of the importance of participatory and gender-sensitive needs assessment and planning arose from staff members who practised various methods in the field. The process was also helped by the dissemination of gender analysis and PRA fieldwork findings to various staff members in MAC and Cooperatives.

Bringing groups of various disciplines together to conduct further PRA exercises is conducive to broad institutionalization, especially if participants identify gender issues in their own research programmes or extension work that they would like to address as a follow-up to the gender analysis and PRA fieldwork.

The following measures to institutionalize gender-responsive participatory agricultural planning were recommended by regional workshops:

Participants of the gender training recommended that each ministerial technical department assign one staff member who would ensure that gender issues are incorporated into the programmes prepared by different departments within the ministry.

At the cross-sectoral level institutionalization was suggested in the form of:

Lessons learned: institutionalization |

|

Training governmental staff of various levels in such methods as gender analysis and PRA creates an enabling environment in which to initiate the mainstreaming of gender-responsive participatory approaches into agricultural development and planning. |

Multidisciplinary PRA field exercises can broaden institutionalization, allowing participants to identify gender issues in their own work which they can address as a follow-up to the fieldwork. |

THE PROJECT SHOWED THAT THE FIELD of agricultural development has a strong need for training in gender-sensitive methods such as PRA and gender analysis. This training should raise awareness of the importance of participatory and gender-sensitive needs assessment and agricultural planning.

Experience and practice in the participatory methods applied by this project, which were considered appropriate by the staff who have participated in the fieldwork, could be applied by other development practitioners. The establishment of teams with multidisciplinary backgrounds to conduct further gender analysis and PRA exercises in at least one district in each region would be an essential follow-up in each of the 25 regions of the country.

In the short term, the following measures are needed:

In the long term, measures are needed that:

The original language version of this case study was edited by Eva Jordans and Nancy Hart.

1 These are: the Fifth International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) Project in Tanzania; the Netherlands-supported WIA, or Women in Irrigated Agriculture and Related Activities, which was partially implemented by FAO (GCP/URT/103/NET); the SNV-supported Traditional Irrigation Improvement Programme (TIP); agriculture extension support; rural credit support schemes; dairy product development; increasing rural women's food productivity; and the National Farming System Research Programme.

FAO. 1995. Women, agriculture and rural development. Fact Sheet Tanzania.