1. INTRODUCTION

This paper was drafted as fisheries allocations in South Africa were undergoing a major revision. Therefore, it deals only with the recent allocation procedures; the outcome of the present process, which is expected to culminate in the issuing of "medium"term fishing-rights for the year 2002, may bear no resemblance to that presented herein. However, so as to present a balanced perspective, the views and procedures leading up to the 2002 allocations are also presented. Many of these may not be factors that are ultimately used by the State management authority in the 2002 allocations.

Fisheries in South Africa are passing through a critical phase of transformation and change. This process has unquestionably resulted in major disruptions to the fishing industry as a result of administrative instability and persistent litigation by the industry. At the centre of the debate has been the re-allocation of fishing-rights with "historical" rights-holders defending their past rights while many new potential fishers apply for fishing access-rights which can only come at the expense of the existing fishing industry. It would be foolish to draw comparisons between the South African allocations-process and those in other areas in the world because the South African situation presents a unique political and socio-economic situation, although the principles and conflicts associated with the granting of fishing-rights remain similar throughout the world. The transition in South Africa's fisheries may be compared with Namibia where the authorities, after independence, immediately set about drafting a fisheries policy and legislation. Namibia has in fact recently completed its first period of the allocation of "long-term" fishing-rights (seven years). Where South Africa and Namibia differ however is their respective points of departure in the allocation process. In Namibia all rights issued from the outset were "new" and in theory consideration of historical performance was not an issue in the granting of future fishing-rights (although many groups, particularly South African interests, who had been active in Namibian waters under the International Commission for the South East Atlantic Fisheries (ICSEAF) acquired rights through Namibian holding-companies or other restructured companies).

South Africa, having undergone a profound political transition in 1994 from a minority-controlled state to a new democracy that effectively empowered the whole nation, set about correcting the discrimination of the past. Fisheries have not escaped this process and in October 1994 the Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism appointed a Fisheries Policy Development Committee (FPDC) with a view to developing a new fisheries policy for the country. Between 1994 and 1996 the FPDC set up a working committee and technical subcommittees to organise and bring together inputs from many interest groups and people. This resulted in the writing in 1997 of a White Paper based on the FPDC report and subsequently the enactment of the new Marine Living Resources Act No. 18 of 1998.

Amongst the many stated aims of the Policy were the following extracts that are related directly to the granting of access-rights:

v. A system which ensures greater access to the resource by those who have been denied access previously.

More than seven years after the start of the fisheries policy development and three years after the introduction of the new Act, and the various attempts to follow the stated aims and guidelines using the new allocation procedures and structures, the fisheries in South Africa are seemingly unstable and persistently disrupted by litigation. This prompted the Minister of Environment Affairs and Tourism to declare a moratorium on the granting of fishing-rights for 2001 thereby effectively carrying over the rights held in 2000, but still with no guarantee to rights-holders of any form of tenure.

Since 1990 up until the present - 2001 - and into the future, the allocation of fishing-rights in South Africa therefore presents an interesting, but as yet unresolved case study. South Africa is a rich fishing nation although fishing contributes less than 2% to the country's gross domestic product (GDP). From a political perspective, however, it carries far more weight and the subject of fishing-rights allocations has been an emotional and sometimes acrimonious issue.

A case study of the largest and wealthiest of the fish resources in South Africa: hake (Merluccius spp.), has been selected to describe the rights-allocation issues in South Africa. Not only is this hake resource a strong competitor on the international whitefish market, it also is the subject of historical rights-claims from previously disadvantaged person (HDPs)1 . Further, it is a dynamic fisheries sector, which has undergone major shifts in effort from the historical trawl fishery (starting in 1900) to the introduction of longlining (from 1983), and more recently the development of a significant handline fishery for hake. This has resulted in an enormous increase in the effective users of the resource, who now range from the sophisticated industrial trawl sector (with large factory/processing vessels and land-based value-adding processing plants) to the smaller labour-intensive, but highly selective, longline sector (targeting large mature adult hake) and the small-boat (handline) operation analogous to small-scale subsistence fishing but which in reality is developing into a highly profitable and competitive fishery.

2. THE NATURE OF THE HARVESTING RIGHTS FOR HAKE

2.1 Past situation

Up until 1996, the offshore- and inshore-trawl sectors (hake-directed fisheries with associated bycatch) contributed up to 80% of the total value of all fisheries in South Africa (Table 1) - a proportional value that is still valid in 2001. The only other fishery in which hake was reported up to 1996 was the highly controversial hake longline sector. South Africa's most valuable fishery commercially is therefore the demersal fishery, a fishery dominated by deep-sea trawling for the two Cape hake species: Merluccius paradoxus and M. capensis, the former (the deep-water species) being predominantly caught by trawlers, and the second (the shallow-water species) being caught by the inshore-trawlers, longliners, and by the handline sector.

Table 1

Comparison of nominal commercial catches (whole mass) and wholesale values of different fisheries sectors in South Africa

* Hake sectors relevant to this discussion document.

2.2 Trawl sector

The trawl fishery targeting hake developed at the start of the century and grew rapidly after World War II to peak at more than 300 000t in the early 1970s. It then went into decline, which prompted the implementation of a larger minimum mesh-size in 1975 and the declaration of a 200 nautical mile fishing zone in November 1977. The exclusion of foreign vessels and a conservative management strategy with effect from 1983 led to a gradual recovery in catch-rates. In fact, hake catch-rates by the mid-1990s had returned to levels last seen in the late 1960s. Since the late 1970s the hake fishery has been controlled largely by means of company-allocated quotas within a total allowable catch (TAC), with limits on the number of vessels permitted in the fishery, and with closed fishing areas. The hake fishery was also split between two trawl sectors: "deepsea" and "inshore".

The deepsea trawl fishery operates primarily on the shelf edge in waters deeper than 300m, from the Namibian border south to the south coast (including the whole Agulhas Bank) and up the Indian Ocean coast of South Africa to Port Elizabeth, the eastern-most location of the fishery. The target species is the deep-water hake, Merluccius paradoxus. A few foreign vessels still operated in South African waters until 1992, but by 1993 the only foreign quota of hake was 1000t awarded to a joint-venture with Moçambique through a bilateral fishing agreement. Separation of the two hake species is difficult and until recently the assessment of the hake stocks had not differentiated between the two species. Further, the rights-allocation of the TAC has also not differentiated between the two hake species although allocations to the Inshore and Deepsea sectors do, to some extent, limit the catch of each species.

Allocations in the deepsea sector have formed the backbone of the hake fishery and have historically been dominated by a few large operators (Table 2). Since 1994, however, the deepsea sector has undergone considerable change with the inclusion of many new entrants (Table 3). Since 1978, when only four groups were active, the sector has evolved from six companies in 1979 to 18 entrants prior to the introduction of the Quota Board. Companies continued to enter between 1991 and 1998, reaching 55 in number when the Fisheries Transformation Council was introduced, and 57 in 2001 when the moratorium was introduced. This represents a substantial change in the number of deepsea rights-holders, particularly since political transition (although allocations are still dominated by a few large companies with respect to quota-mass).

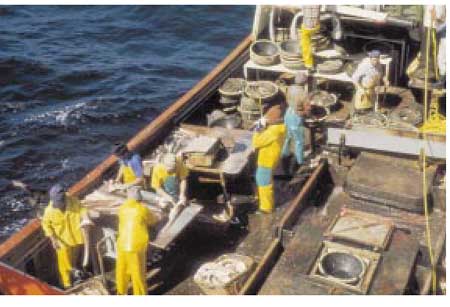

A full net of deepsea trawl-caught hake being emptied into a factory stocker pond

Table 2

The status of the hake fishery and number of quota

(rights)-holders relative to some of the other major fishing sectors in South Africa in 1996

The small inshore trawl fishery operates along the South African south coast and typically comprises mostly small side-trawlers working in waters shallower than 110m on the Agulhas Bank. The fishery lands only 6% of the national hake2 catch, but rights in this sector are normally linked to the allocation of sole (Austroglossus pectoralis) which, in addition to hake, is also an important target fishery. The nature of the fishery is quite different from the deepsea sector and although small, it has been stable and has undergone rationalisation not only of the number of rights-holders, but also strict effort control has been maintained in terms of vessel size and capacity (Table 4).

Table 3

Historical allocations and the structure of hake allocations

Table 3 (continued)

Table 4

South Coast Inshore Fishery: Changes in Structure between

1982 - 1989 - 1995 - 2001 in South Africa showing the dramatic increase in new rights-holders

The allocation of rights in the hake trawl sector have, however, become increasingly complex with recent concerns over the effective increase in exploitation of the shallow-water hake by the longlining and handlining sectors. Biological (stock) concerns are clearly becoming an integral part of the "rights" debate as the sector allocations will undoubtedly have implications for the effects of the fishery on stock sizes. Note also from Table 4 that the number of rights-holders in the sector in 1998 was 11 and two new allocations have since been granted.

A typical catch of hake from an inshore sidetrawler. Note that the operational area and techniquesdiffer considerably from the deepsea sector

2.3 Hake-directed longlining

By 1996 the TAC of hake had risen from 120 000t in 1983 to about 150 000t. At that time entrepreneurs lobbied for the introduction of experimental longlining, a fishing method used successfully in European waters for hake, as there promised to be a valuable fresh-fish export market from South Africa for catches made using this technique. Primarily because of the pressure by hake rights-holders to keep new entrants from the hake sector, the fishery evolved into a kingklip-directed (Genypterus capensis) experiment and away from the intended target species of hake. The subsequent demise of the kingklip stock and short duration of the introduction of rights to kingklip (two years between 1988 - 1989) resulted in many of the experimental kingklip rights-holders being compensated in the form of small hake-trawl quotas3 . After the closure of the "kingklip-directed" longline fishery in the early 1990s, local fishing entrepreneurs exerted considerable political pressure for the introduction of hake-directed longlining in South Africa. Longlining is seen as a less capital-intensive method of catching hake and a means by which access to the hake resource can be broadened. Part of the hake TAC was therefore set aside for a scientific and socio-economic experiment to test the advisability of hake-directed longlining. This experiment, which started in 1994 and ended three years later, was shrouded in controversy, but as shall be illustrated later, provided an innovative means of creating access to the hake resource during the experimental period.

The hake longline experiment started at the time of democratic change in South Africa and created enormous expectations from HDPs as a potential means of entering the hake fishery. The allocation of hake longline rights subsequent to the hake longline experiment provides a further complication in the recent rights allocation process in South Africa and has been the source of persistent litigation. It was also a major factor contributing to the introduction of the moratorium on new entrants to the fishery in 2001. Litigation, appeals and rights-allocations relating to the hake longline fishery are still outstanding from 1998.

2.4 Hake handline sector

The complexity of the allocation process in the management of the hake resource has been further complicated by the development of a hake handline fishery. The origins of the handline hake fishery can be traced back to the late 1980s. Historically hake have always been caught by commercial handline fishers, but no real commercial value was attached to the species (due primarily to the higher value of other available species). The quantities that were caught were small and hake were accepted as a bycatch in linefish-directed fishery for the numerous other species. No quota was set aside for the hake caught and the only form of control was through limitation of effort (numbers of boats), indirectly through the linefish management. Vessel-owners and fishers who had traditionally targeted squid and linefish explored the potential availability of alternative resources on the South Cape Coast as a commercial "filler" activity when the other species were not targeted, because there was a desperate need to keep vessels and crew economically active for as much of the year as possible.

Infrastructure existed for the processing of the other species (e.g. linefish and squid) and the development of the hake handline fishery resulted in a logical extension and growth of the land-based processing facilities. An important consequence of these developments was the increase in local employment and a natural value-adding contribution to the regional economies.

A typical South African hake-directed longline operation.The fishery is highly size selective targeting spawning hake

A typical handline hake-directed operation Small open deck ski or deckboats are used. Fishing is by line only and is conducted in deep water (forline fishing) and the product is landed daily on beaches and in smallharbours around the South African south and east coasts.

The fishery was, however, started at a time when the old Sea Fisheries Act of 1988 was enforced. The growth of the fishery was well known to the state management authority, however because of the ongoing rights-allocation issues in the major commercial sectors, no control was exerted over the growth of the fishery as it developed. Both species of hake fell within the "exploitable" list with regard to the "Linefish Bag Limits" in terms of the old Act, thereby enabling holders of commercial (A) or semi-commercial (B) linefish permits the right to catch an unlimited quantity of species on the list (provided they did not exceed the limit of 10 hooks on a single line). Further, recreational fishers were also permitted to catch in total 10 fish per day of any species defined as "exploitable". This ruling has remained in force, even though the promulgation of the Marine Living Resources Act (September 1998) replaced the old Act and placed hake on the "restricted" list that limits all linefishers (commercial and recreational) to a maximum of five hake per day. The new regulations did not, however, differentiate between "commercial" and "semi-commercial" linefish operators, but they did specify a "recreational" activity. As the state authority (Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism: Directorate of Marine and Coastal Management) was not in a position to reassess the status of the fishery when permits expired in mid-1998, extensions to permits were granted that, up to mid-2001, were all still valid. Further confusing the issue is the fact that until such time as the applications for new rights in the sector are called for, and processed in terms of the New Act (1998), fishers may continue to operate in terms of the old Sea Fisheries Act. However a second interpretation is that from a strictly legal point of view, the transition period from the old to the new Acts (six months, Section 85) expired on 1 March 1999 leaving the linefish operations in a legal void. Permits have therefore been extended to accommodate the time taken to process applications, but in the meantime the transition period set aside by the Minister has expired.

The growth of the handline hake fishery since 1984 is illustrated in Figure 1 (below) and the value of the fishery to the regional economics is shown in Table 5.

Rights in the hake sector can be divided into the following "sub-sectors" (Figure 2):

Clearly, with an unstable "fisheries" environment in which tenure is uncertain, the sector exploiting the most valuable single fish resource in South Africa is confronted with an uncertain future in which many historical claims to a right to catch hake can be made from the developers (who it may be claimed were advantaged through the previous political dispensation). Further, recent performers in the hake longline sector who took part in a legitimate experiment to develop the hake longline fishery have strong arguments for hake rights. Then there is the almost completely unstructured handline sector with an unclear legal status, but one that offers potential for greater inclusivity and future for small operators.

Figure 1

Historical handline catches of hake

Data for 1998-1999 are estimates and for 2000 catches are based on available catch data submitted by the industry. Data for 2001 is a predicted figure extrapolated from present catch rates.

Table 5

Economic considerations of the Handline Fishery for hake(Figures are

approximate up to the year 2000)

3. THE METHOD OF ALLOCATION

3.1 Policy objectives

Figure 2

Representation of the complexity of the different fishery sectors for which

hake allocations are prescribed

The allocation of fishing-rights and the introduction of quotas first started in South Africa in 1978. Over time the process has evolved and in 1986 a special commission was appointed by the then Minister of the Environment to investigate the fisheries allocation process (the Diemont Commission). Judge Diemont gave considerable thought to access-rights and related matters and proposed that the allocation of quotas be entrusted to a statutory board. This recommendation was accepted by the Government by way of its 1986 White Paper, and the Sea Fishery Act 1988 made provision for the establishment of a Quota Board (Table 3). The first Board became operative in 1990. The Quota Board was appointed by the Minister responsible who determined the number of members and the quorum. The chairman had to meet certain requirements in respect of possessing a legal background and no person with interests in the fishery could serve. The Act also stipulated that "a person in the employment of the State" may not serve on the Board. Notwithstanding the fact that politicians are not regarded as being in the employment of the State, their appointment would be contrary to the aims of the Board, namely to remove quota allocation from the political arena. The Board's function consisted of the allocation of quotas to persons according to guidelines approved by the Minister. The Quota Board could attach conditions to its quota allocations and no quota could be transferred without the Board's approval. The Board exerted control over access-rights in the hake, Agulhas sole, pilchard, anchovy, West Coast rock lobster, South Coast rock lobster, and abalone sectors.

The new fisheries policy objectives introduced a new dynamic to the allocation process. Extracts from this policy stated:

"Marine resources are by definition a national asset and the heritage of all citizens. However, in order to ensure the sustainability of the resource, it is necessary to limit harvesting levels, and therefore access to the resource. Limiting entry creates a privileged group of sectoral actors who enjoy access to living marine resources, in contrast to all other South Africans who do not. In South Africa, access to these resources has not always been fair and equitable. As a result, the industry is faced with numerous problems which even threaten the sustainability of the resource itself".

Other broad policy objectives include the following:

3.2 Process used in determining the allocations

Policy development (including the sensitive issue of access-rights) in South African fisheries is ongoing. The new Marine Living Resources Act 1998 remains the cornerstone of South Africa's fisheries development although there have been shifts in management strategy.

From 1991 to 1998 all allocations were made by the Quota Board. This body introduced many new entrants into the different fisheries sectors. This was however, an unpopular system. Although the Quota Board made its allocations according to agreed criteria, the quotas were generally perceived to have been allocated arbitrarily, and often unfairly. Consequently, the industry remained steeped in uncertainty and insecurity throughout, i.e. in companies large and small. This organizational structure is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Structure used in the allocation of rights prior to the introduction of the Fisheries Transformation Council (1998)

The South African commercial fishing industry has quota and non-quota sectors with the former being significantly larger in terms of value and quantity. Quotas (catch- or output-controls) to catch a stipulated quantity of a specific species have historically been allocated to individuals or companies. This is the case in the hake-trawl sector. In the hake-longline example, the process has been complicated initially by "illegal" fishing, then the introduction of an experimental allocation and then attempts at introducing short-term rights (year-by-year allocations). In addition, as with the hake-handline sector, permits have also been granted to individuals or companies to catch a quota species within a non-quota controlled fishing regime (the linefish sector targeting traditional linefish species with no limitation, or very limited restrictions, on the quota species).

3.3 Marine Living Resources Act No. 18 of 1998

With the introduction of the new act (May 1998) came the introduction of the Consultative Advisory Forum (CAF) and the Fisheries Transformation Committee (FTC) and the phasing-out of the Quota Board5 . The CAF effectively replaced the Sea Fisheries Advisory Council (SFAC - see Figure 3) and the FTC, whose main function was "to facilitate the achievement of fair and equitable access to the granting of fishing-rights".

The appointment of the Fisheries Transformation Council (FTC) was fraught with problems leading to the resignation of most members at the end of 1999. To date these members have not been replaced, the status of the body remains uncertain, and there is general uncertainty as to whether the body will remain in place or, whether an alternative will be sought. At present (early 2001) there are initiatives to form a "Rights Allocation Unit" whose primary objective will be to allocate medium- and long-term rights (effectively replacing the FTC).

Applications for fishing-rights in the 1999/2000 fishing season were published in the Government Gazette in August 1999, outlining the periods between which applications for each fishery had to be submitted. For hake trawling (deepsea and inshore) and hake longline, for example, there was a one-month period in which to apply, from mid-September to mid-October. The notice stated that only South African citizens might apply (as individuals), or companies/ closed corporations/ trusts, in which the beneficial interests were held by South African citizens.

Application forms were standardised for all sectors. The basic form required name of applicant / company information, species applied for (and quantum), and a declaration of the size of the entity6 . Applicants had to declare how and with what means (e.g. by vessel) they intended to harvest the right applied for and had to submit to the office of Marine & Coastal Management (M&CM) an original "Application Form" plus 10 copies. In addition a comprehensive set of annexures had to be submitted with each application that included the following:

Annexure 1 - Previous rights and fishing performance - Specific criteria:

Annexure 2 - Company structure and profile

Annexure 3 - Proof of registration of company and share-holding

Annexure 4 - Identity documents of all shareholders

Annexure 5 - Certified vessel safety certificate and South Africa registration certificate

Annexure 6 - Charter Agreement

Annexure 7 - Joint venture agreements (if applicable)

Annexure 8 - Members' involvement in fishing (see application)

Annexure 9 - Employment and employee benefits

Annexure 10 - Product enhancement:

Annexure 11 - Resource and Environmental criteria

Annexure 12 - Transformation

All documentation had to be verified by a Commissioner of Oaths and a sworn statement made that the information contained in the application was the truth.

3.4.3 Selection criteria

Simultaneous to the call for applications, "Selection Criteria" and "Guidelines" for the assessment of applications in respect of the rights applied for were released. These selection criteria were similar in structure to the application form.

"Section 0: General:" and "Section 1: Basic Information" mirrored the application form as specified in the Annexes above, and was neither weighted or scored.

"Section 2: General" was to be weighted and scored7 and formed the basis for determining much of the allocation. The focus in this section is summarised as follows:

In addition to the above, special criteria were applied to the "Linefishery" in which applicants had to demonstrate dependence on the species applied for and had to prove they were bona fide fishers. All applicants also had to submit business plans and a framework for a business plan was appended to the Selection Criteria document along with a "Code of Conduct for Fishing in South Africa".

3.4.4 Processing procedures, data capture and administration

Processing of these applications (in 1999 for the 2000 allocations) was an enormous task. The Department responsible had to accept and distribute one original and 10 copies of each application (the purpose of the large number of copies was for distribution to each member of the committees dealing with each species or sector). The exact procedure that was followed had not been fully determined, although the general approach for all sectors is described below.

The processing and adjudication of applications was therefore done under the control of the Chief Director, Sea Fisheries (now Marine & Coastal Management - M&CM). Teams, or management committees, for each sector were selected and individuals were given copies of each application, who then scored a particular section of each application (for example the section on economics was evaluated and scored by an economist). Scoring was however at the discretion/ interpretation of the individual. These scores were also weighted and the totals subsequently calculated.

It should be noted however that the deliberations of each committee and the exact scores were generally withheld from the public, although applicants with their legal advisors were subsequently permitted to view applications and scores (as was the case in the longline fishery). It is also emphasized that the process was taken to a point of refinement in which poor-scoring candidates were removed and only strong candidates were given further consideration. Ultimately, the final decisions on successful applicants rested with the Chief Director who then made his recommendations to the Minister.

Many thousands of applications were received for all sectors. However, the hake trawl sector had relatively few applicants, as the nature of the fishery and the potential capital outlay resulted in fewer applications than the hake longline sector for example, for which almost 1000 applications were received.

For the deepsea trawl sector, prior to the year 2000, applications to participate in this sector were received from 52 rights-holders. In the first allocation released, this number was drastically reduced to 28 with one "New" entrant. The subsequent threat of legal action and the likelihood of an interdict against the allocation process forced a review of the decisions that had been made for this sector. Through negotiations between the "traditional" deepsea sector, which consisted of the major stakeholders, it was agreed that a "donation" of up to 10 000t of hake would be made for the express purpose of introducing new deserving entrants into the sector. As a result no rights-holders lost their rights, but four new entrants were accepted, effectively increasing the number of rights-holders in the deepsea sector to 56. Each of the four new entrants was allocated 750t of hake. This led to further controversy, as the original purpose of the "donation" was to accommodate deserving new entrants, and two of the successful "new" entrants were considered to be "front" companies for existing stakeholders.

Figure 4

Processing of applications for hake rights in South Africa in 1999 (for the 2000 fishing season)

The case of the inshore trawl sector was somewhat different as rights had to be linked to the additional allocation of sole quota. As this hake sector comprised only eleven applicants, only two new entrants (HDPs) were accepted, thereby increasing the number of stakeholders to thirteen.

The hake longline sector proved to be the most difficult as it was a relatively new group and there were high expectations from the many new applicants and also from previously disadvantaged persons and groups. A further complication was that many applicants had participated in the experimental longline fishery for four years and obviously believed they were deserving of rights (even though in the experimental period no guarantee of future rights was given)8 . The result of the application evaluation and scoring, in which applicants were systematically reduced in number (e.g. all those scoring less than 50% were rejected in the first evaluation) was that some 100 "top" applicants were then considered for rights by the Chief Director, i.e. the scoring and evaluation ended at this point and the final decision was taken by the Chief Director. The outcome was that there were 45 successful applicants who subsequently fished their rights in the year 2000.

In the case of the Line fishery, at this point in time, hake were not differentiated from other linefish species. The outcome of this application period will, however, have important consequences for the future of the hake-directed linefish fishery. To date (three years after application) no rights in the linefish sector have been granted. The significance of this is that in this period the hake-directed linefish fishery has developed into a fully structured and economically-viable sector. It has been separated from other linefish species, but carries the complication of how hake-directed performance (a likely selection criteria for future rights) in 2002 will be evaluated. Further, because of its low capital requirements for entry into this fishery, and the potential benefits to coastal communities and regional economies, the hake handline sector is seen as ideal for new entrants of previously disadvantaged backgrounds.

The Marine Living Resources Act (MLRA) allows for appeals to be made directly to the Minister against "any decision taken by any person acting under a power delegated in terms of this Act or section 238 of the Constitution" and appellants are afforded the opportunity to "state his or her case" (re Section 80 of the MLRA). Many appeals were received, particularly from the longline applicants. It should also be noted that a precedent had been set in 1998 in which the West Coast Rock Lobster fishery had been stopped as a result of an interdict against the Minister. This resulted in the closure of the fishery for a period. In the case of the hake longline fishery the Supreme Court (after legal representation by groups of unsuccessful applicants) set aside the allocation made by the FTC and ordered new allocations from more than 900 applicants to be reviewed again9 Subsequently the members of the FTC resigned and the newly appointed Deputy Director General (as opposed to the former Chief Director) was tasked with considering the appeals.

This was duly done and some 150 appeals were upheld and a small allocation approximating 30t was granted in the middle of the season (in addition to the 45 successful applicants with 100t each). No sooner had the permits for the "appeal" hake been issued and the process was again successfully interdicted (only the "appeal" fish - the original applicants continued fishing and were unaffected by the litigation). As a result of this litigation the department was again instructed by the Supreme Court to review the appeal applications. At the time of the drafting of this paper the longline issue had not being resolved and one further attempt at reviewing the applicants appeals had been rejected. The status of the longline fishery for hake therefore remains uncertain and legally unresolved.

The evolution of the Fisheries Policy Development, the disbanding of the old allocation system (Quota Board), the promulgation of the Marine Living Resources Act (replacement of the Sea Fisheries Act), and the subsequent attempts to use these new structures as tools to apply the Fisheries Policy and to allocate rights in South Africa, was largely unsuccessful up to the end of 2000.

In reality, however, if the status of the hake resource since the 1994 elections in South Africa is reviewed, it can be seen that significant changes in the numbers of rights-allocations have indeed been made. Rights-holders however have no tenure in the form of medium- or long-term rights. The fisheries sector remains highly unstable. In the case of the deepsea trawl sector many new entrants have been added, but it can be argued that for a highly industrial capital-intensive fishery, there are too many allocations which are too small for viable deepsea operation. Attempts in 1999 to reduce the number of entrants failed due to the threat of litigation, and in reality all that has happened is an increase in the number of rights-holders, thereby spreading the effort within a relatively stable Total Allowable Catch (TAC). The objective of future allocations will therefore in all likelihood focus on consolidation of the smaller allocations into viable units. Linked to this process are the socio-political objectives, focusing on "transformation" of the industry. No clear definition of transformation in the fisheries sector has been made, but it is obvious that the pace of transformation since 1994 has been questioned (political perspective). The need for greater inclusivity of historically disadvantaged persons (HDPs) is also in direct conflict with biological and economic objectives (as they could lead to uncontrolled fishing or over-exploitation of the resource and unstable markets).

Perhaps the best example of both industrial stability and good fisheries management is the inshore trawl sector. There are few rights-holders and the introduction of two new (HDP) allocations (rights) has been achieved without major disruptions or litigation.

In direct contrast however, the introduction of a hake longline sector has proven highly disruptive to the attempts to put in place a structured allocation-process. There are many reasons for this - however the most influential of these, accounting for the failure of the rights allocation-process and the subsequent litigation - is the fact that historically it can be argued that there can be no claim to rights in the sector. As the fishery is lucrative and the demand for fresh longline-caught hake is high10 , combined with the relatively low entry-capital input required, expectations from potential users is high. Many argue that having taken part in an experiment to test the viability (economic and biological) of hake-directed longlining, they have a historical right to access in the sector. Precisely where this sector will go with regard to future allocations is unclear, because although there is an existing group of rights-holders, there remain upwards of 150 others who were granted rights on appeal (before being stopped by interdict). Generally, dissatisfaction within the interested and affected parties is high, and further legal action as a result of the pending allocation (2002) is almost certain.

Although no attempt has been made in the past to allocate hake handline rights, this fishery has been used in this paper to demonstrate that with respect to its status, it is probably in a similar position to the hake longline fishery in 1997 (at the end of the experimental period). The sector has been permitted to develop, creating related infrastructure and socio-economic benefits to regional economies. The declaration of a "Crisis" in the linefish sector at the beginning of 2001 has complicated the pending sectoralisation of the hake handline fishery. Applicants who believe they have performed in the sector are likely to find themselves marginalized as a result of severe limitations on the number of likely entrants in the sector, as well as having to compete with the transformation objectives and likely favouring of previously disadvantaged persons and/or "transformed" companies. The handline sector of the hake fishery adds a new dimension to the hake rights-allocations, placing further demand on the limited global TAC for the species.

Allocations for the subsectors (deepsea, inshore, longline, and now handline) will potentially increase in the year 2002 the number of "users" of the hake resource to upwards of 300 rights-holders (i.e. 50-60 deepsea trawl, 13 inshore trawl, 45 - 150 longline, and 130 or more hake handline). In 1979, at a time when the hake stocks were recovering and catch-rates in the fishery increasing, there were six rights-holders. In 2001 there are 104 legal rights-holders and over 350 hake handline operators and 150 longline rights on appeal.

Towards the end of the year 2000, with the repeated court interdicts and other threatened litigation, the Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism declared a moratorium on the issue of all fishing rights in 2001 (this had to be done through the passing of a temporary amendment of the MLRA, whereby a moratorium of one-year only was granted). The purpose of this was, as a temporary measure only, to introduce some stability to all fisheries and to allow time to restructure the allocation-process with a view to introducing medium-term rights in 2002.

The office of Marine and Coastal Management (M&CM) under the directive of the Minister initiated a full consultative process whereby the interested and affected parties in all fisheries sectors were actively engaged and asked to deliver "Rule Books", the purpose of which was for anyone (individual, organisation, industrial body) to submit for consideration their criteria for selection and allocation within their sector of interest. After having engaged all fishers, several draft documents were produced by M&CM for distribution amongst fishers that discussed firstly a "Fisheries management plan to improve the process of allocating fishing rights" and secondly "Stability, Transformation and Growth". At the time of writing the following processes were active.

The time-frames for the completion of the above were limited, with the seasons for some fisheries commencing before the end of the calendar year e.g. West Coast rock lobster and abalone. The call for applications (by Government Gazette notice) was pending at the end of July, with the likely first submission of rights applications for 2002 commencing in mid-August 2001.

1 The expression "HDP" is commonly used in South Africa referring to "historically disadvantaged persons" who prior to democratic elections in 1994 were unenfranchised.

2 The target hake species in this sector is the shallow-water hake, Merlucccius capensis

3 These new hake trawl-rights were too small to trawl independently and are a complicating historical factor in the hake rights-allocation process.

4 There are several ways whereby the existing large players can enable others to achieve the empowerment criteria which will enable them to compete for access-rights including: (a) expanding equity ownership in companies, (b) restructuring of the industry in order to move in the direction of larger proportions of the quota being sold to small-scale fishing operators, (c) encouraging contracts with fish-processing companies, (d) helping small-scale operators improve efficiency and unbundling mergers, and (e) the formation of co-operatives and other forms of formal commercial cooperation.

5 The new Act stipulated that the Minister could exercise the powers of both Acts for a period of six months after the promulgation of the New Act. This in itself became the subject of later litigation relating to the hake longline allocations for 1999.

6 Entities applying for rights were asked to declare their size or class (Large, Medium, Small, or Very Small, based on either the number of employees, annual turnover or gross asset value) with reference to the National Business Act of 1996 (Act No 102 of 1996).

7 Weightings and scores per category were not stated, although the scoring system actually used became known after the allocations had been made and formed part of the basis for subsequent litigation.

8 Note that in the longline experiment, allocations had been successfully given and managed to different sectors including: "deepsea", "tuna longline" (comprising tuna boats), and "inshore longline" aimed at coastal communities (and for which a successful tendering scheme was used to allocate tranches).

9 The basis for the appeals was that there had been inconsistency and irregularities in the application and scoring process and that all applications had to be re-evaluated.

10 The fishery operates in a lucrative but unstable environment that is prone to market saturation and high freight costs (for fresh-fish export).