1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Distribution and life history

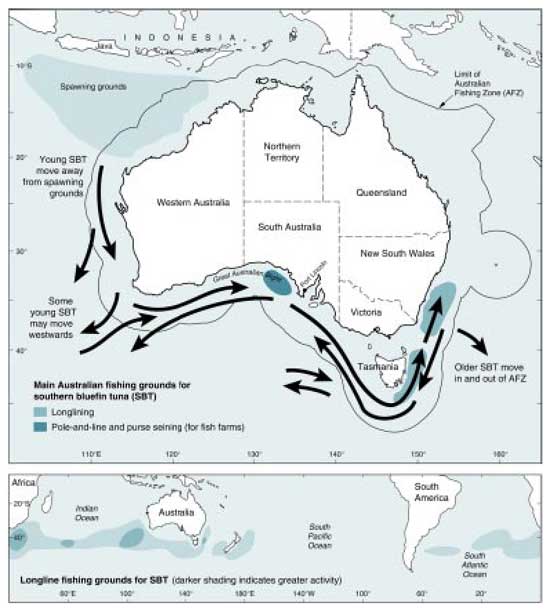

Southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) is a highly migratory species, apparently forming a single stock, with a single spawning area, although as mature fish they probably have a circumpolar distribution between latitudes 30º and 50º South. Figure 1 shows the geographical range of the different life-history stages of this species.

Figure 1

Map showing distribution of the different life-history stages of Southern Blue Fin Tuna

Map credit: Bureau of Rural Sciences, Australia

Spawning occurs between the months of September to March in the Indian Ocean in an area generally south of Java, between latitudes 7º and 20º South. Juvenile fish migrate down the west coast of Australia with one to three year-old fish (35-75cm) appearing in surface schools off the southwest coast of the continent. Further east along the southern coast of the continent larger two to six year-old fish (50-120cm) occur in surface schools. While immature fish are generally associated with coastal and continental-shelf waters, some apparently move offshore into the waters of the West Wind Drift (40-45º S) from about 3 years of age, and have been caught as far west as South Africa.

Southern bluefin tuna (SBT) mature at lengths of about 120-130cm and 7-8 years of age. Mature fish lead an oceanic pelagic existence. Whether individual fish spawn annually or at less frequent intervals is unknown. Southern bluefin tuna live for at least 20 years reaching 200kg in weight and 200cm fork length (Kailola et al. 1993).

1.2 The Fishery

A seasonal commercial (troll) fishery from September to December, targeting surface schools of juvenile southern bluefin developed off south-east Australia in the mid-1930s. Fish caught were destined for canning. A similar fishery developed off South Australia a few years later with a fishing season from February to April.

The fishery received a major boost in the early 1950s with the introduction of the pole-and-live-bait fishing method. In the late 1970s this method was extended to waters off southern Western Australia. In the mid-1970s the introduction of purse seining gave a further boost to the fishery off New South Wales and South Australia.

The Japanese fishery for Southern bluefin tuna using drifting longlines commenced in the spawning areas south of Java by the late 1960s, and then extended from east of New Zealand across the southern Indian Ocean into the South Atlantic (Kailola et al. 1993).

1.3 Markets

The Australian fishery for SBT initially aimed at satisfying the domestic market for canned tuna. As such it was considered a relatively low-value species. By contrast the Japanese fishery was directed at supplying the premium sashimi market for which it is reportedly the preferred species.

Early attempts by Australian fishers to penetrate the Japanese market proved unsuccessful, apparently because of the poor selection of fish and inappropriate handling. However, following the declaration of the Australian 200nm fishing zone (the AFZ) in 1979, which reduced Japanese access to some traditional fishing grounds, Japanese interests worked with Australian fishers to overcome these difficulties. Almost all Australian produced southern bluefin is now air-freighted to Japan for the sashimi market.

1.4 Catches

Table 1 shows the annual catch of southern bluefin tuna by major fishing nation since 1960. The Japanese catch peaked at 77 500t in 1961 but by 1980, despite increasing fishing effort, this had declined to less than 30 000t per annum. The Australian catch peaked at 21 500t in 1982. However, this catch figure by itself told only part of the story. The fishery off Western Australia targeting mainly one to three year old fish had provided most of the growth in the Australian fishery in the late 1970s. The actual number of fish taken by the Australian sector was increasing much more rapidly than the total Australian catch. This is illustrated by a comparison of catches for the years between 1974 and 1980: while the total weight of catches taken in each of these years was comparable, the number of fish in the 1980 catch was some 55% higher than in the earlier year. At the same time the number of surface schools appearing off the Australian east coast had dramatically declined, and by the early 1980s their appearance in this area had all but ceased.

1.5 Scientific assessment

Annual trilateral meetings of research scientists from Japan, Australia and New Zealand have been held since 1982. The major conclusions of these meetings has been that there has been a major decline in the size of the parental stock of SBT since the 1950s. In 1984 scientists from the three countries agreed that between 1967 and 1975 the spawning stock had been reduced to about 210 000t, or to about 25% of the virgin biomass. The biomass appeared to have stabilised at this level until about 1980. Scientists believed that the increased catch of small fish after that date had reduced the number of fish surviving to spawn. This had been reflected in a reduction in the number of mid-sized fish in the Japanese and New Zealand catches (Anon. 1984). A global total allowable catch (TAC) was agreed between Australia, Japan and New Zealand in 1985 in response to this advice. For that year the global TAC was 38 650t. This was reduced progressively to 11 750t in 1989. This global TAC was in 1989 divided between the three nations as national TACs under a trilateral agreement as follows: Japan 6065t; Australia 5265t; and New Zealand 420t. Each nation is responsible for managing its own national TAC. This paper deals only with the arrangements made by Australia to manage its national TAC.

Table 1

Catches of southern bluefin tuna, by country, fish numbers and weight, 1960 to 1986

Source: Geen and Nayar (1989).

It should be noted that these management arrangements are complicated by the fact that much of this fishery is in international waters and arrangements made under the trilateral agreement are not binding on other nations, which are free to expand their activities in the fishery on the high-seas.

1.6 Management of the Australian sector of the southern bluefin tuna fishery

The Australian sector of the southern bluefin fishery remained largely unregulated until the early 1980s. Restrictions on the number of purse-seine vessels licensed to operate had been in force since the mid-1970s. While justified on the basis of uncertainty about the state of the resource, these restrictions were also designed to satisfy complaints from the pole-and-live-bait sector about `unfair' competition from purse-seiners.

Reaching decisions with respect to the management of this fishery was complicated by the fact that the Australian Commonwealth and three state governments (New South Wales, South Australia and Western Australia) were directly involved (the Commonwealth government had jurisdiction outside the three mile Territorial Sea and the individual states within that limit).1 The industry in each area also had its own characteristics and was targeting fish of different ages.

To further complicate the position, until Australia declared its 200nm Fishing Zone on 1 November 1979, it had no control over foreign fishing outside its 12nm fishing zone. It was politically difficult to impose restrictions on Australian fishers when no similar restrictions could be imposed on Japanese and other fishers operating on the same fishing grounds.

2. THE NATURE OF THE HARVESTING RIGHT

The individual transferable quota (ITQ) management-arrangements introduced into the southern bluefin fishery in 1984 was designed to be a fully operational system of transferable fishing rights. The main components of the management regime were given legal force through the Southern Bluefin Tuna Management Plan, made under the Fisheries Act 1952. The basis of management was that each fisher had to hold a Commonwealth Fishing Boat Licence (CFBL) to which a certain number of quota units were assigned. As tuna were caught the equivalent number of quota units were subtracted from those assigned to the CFBL. Once all the quota assigned to a licence had been caught the holder had to either acquire more quota or cease fishing.

In 1984 14 500 quota units were granted (i.e. in that year each quota unit was equal to one kilogram of catch). There are still 14 500 quota units but as the Australian TAC has been reduced so has the weight-value of each quota unit. The catch allowed for each quota unit each year is calculated by dividing the total allowable catch (TAC) in kilograms by the total number of quota units.

The Fisheries Act 1952 made no provision for the leasing of quota, nor did it provide for the recording of third party interests (for example, where quota was used as security). Leasing was dealt with administratively by formally transferring the quota units to the lessee at the beginning of the leasing period, and then formally transferring the quota units back to the lessor the end of the season. Third party interests were also recorded administratively, with an undertaking to advise the third party before any further dealings with the quota units concerned would be processed. There were, and are, no limits on who could own quota, or the minimum or maximum quantity of quota an individual or company can hold.

3. THE METHOD OF ALLOCATION

3.1 Policy objectives

Scientific advice clearly indicated that the level of catch from the southern bluefin fishery in the early 1980s was not sustainable (Majkowski and Caton 1984, Hampton and Majkowski 1986). Two main factors contributed to this: first, the level of total catch (by weight); second, the high number of small fish being taken, especially in the Western Australian sector of the fishery.

To safeguard the future of the fishery a substantial reduction in catch was clearly essential. It was also evident that a reduction in catch of the magnitude required was likely to lead to on-going enforcement difficulties and continuing economic hardship unless a significant reduction in the size of the fishing fleet could also be achieved. In addition, any measures introduced had to address the problem of targeting one and two year-old fish.

The policy objectives from a biological perspective were therefore: (a) to achieve a significant reduction in total catch and a diversion of fishing effort away from one and two year-old fish; and (b) from a socio-economic perspective, to achieve a substantial fleet reduction while minimising social dislocation and hardship.

3.2 Process used in determining allocation

Because of the divided responsibility for managing the southern bluefin fishery that existed at the time, and in response to the disturbing scientific advice coming from the 1982 trilateral scientific meeting, a Tuna Task Force (TTF) was established to consider and recommend future management options. The TTF comprised scientists, industry representatives, plus officers from the Commonwealth government and the state governments of New South Wales, South Australia and Western Australia, with a chairman from Tasmania (which was not directly involved with the southern bluefin fishery).

Following a series of port meetings with fishers the TTF issued a draft `plan of management' in July 1983. The draft plan contained 14 recommendations, the most important of which include the use of catch-quotas, minimum limits on fish-size, limited-entry and further limits on purse-seine operations (Anon. 1983) It was proposed that the plan should come into effect at the beginning of the 1983-84 fishing season (on 1 October 1993). Because of difficulties in reaching agreement on all aspects, this target was not achieved.

In view of the failure to reach an agreement in time, a national TAC of 21 000t was set for 1983-84. This was allocated as follows: 4000t (a reduction of 28%) for the Western Australia sector (west of 127º E); and 15 000t (a 2% reduction) for eastern sector (New South Wales and South Australia). Of the latter, 10 000t was allocated for poling/trolling and 5000t for purse-seining. Two thousand tonnes were held in reserve for `special use' in both sectors (Media Release of 23/9/83 and Ministerial letter to fishers of 13 October 1983). A minimum size-limit of 54cm for tuna was also imposed.

In early 1984 a further discussion paper, prepared by the Australian Fisheries Service at the request of the TTF, was released for consideration by industry. This discussion paper proposed a move to individual transferable quotas (ITQs), removal of the minimum size-limits for tuna, and the freedom to trade quota regardless of fishing area or catching method (Anon. 1984).

At the same time, and to assist with the implementation of whatever arrangements might be finally agreed, a register of boats that had operated in the tuna fishery between 1 April 1980 and 31 October 1983 was compiled. "The boat register is designed to provide boat, catch and investment information to assist in the development of management arrangements to apply in the fishery beyond the 1983-84 season. ... tuna boat operators, who because of genuine reasons have not used their boats in the fishery during the period but can demonstrate special circumstances and significant commitment to the fishery, will also be considered for inclusion on the boat register" (Anon. 1984).

Simultaneously with the work of the TTF and the compilation of the register, a review of the SBT fishery was undertaken by the Industries Assistance Commission (IAC).2 The genesis of this review was a claim by fish-canners in 1983 that imports of canned tuna were having an adverse impact on the Australian fish canning industry. The inquiry was widened somewhat to include aspects of SBT management. The terms of reference specified by the Commonwealth Government for the IAC on 30 November 1983 required it to inquire into and report on:

The IAC's draft report was released in March 1984. It recommended terminating the competitive quota arrangements for the Australian fishery and replacing it with a TAC of about 10 000t (including a western sector quota of 1000t), and a management system using ITQs. It also recommended that the cost of managing the fishery be recovered from fishers with each fisher contributing in proportion to the amount of quota held (Anon. 1984).

After considering submissions made in response to its draft report the IAC released its final report on 28 June 1984. This report recommended a 14 000t Australian TAC for 1984-85 (including 1000t for the Western Australian sector). It also recommended a move to ITQs but that no adjustment assistance be paid to either the catching or canning sectors. It also recommended that the embargo on the importation of tuna for canning be lifted. It further drew attention to the need for both Australia and Japan to take complementary action (IAC 1984).

3.3 Allocation method chosen

Following consideration of the various issues, the Commonwealth, New South Wales, South Australian and Western Australian governments agreed on the following arrangements to come into effect from 1 October 1984:

The decision not to impose a minimum size-limit or to set a separate quota for the western sector was partly the result of a political compromise so as to secure the Western Australian government's support for the arrangements. More important was the advice from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation relating to alleged widespread dumping of undersized (under 54cm) SBT in the 1983 season. In some cases dumping of up to 75% of catch was alleged. Because many schools of SBT were of mixed size, such dumping would create future problems with statistical interpretation (CSIRO letter of 22 March 1984, File F84-85).

The two-month closure and the ban on fishing north of 34º South were designed to restrict the targeting of small fish. It was believed that because small tuna attracted a lower price, quota-trading would lead Western Australian-based fishers to sell quota to other areas. In view of this, it was argued, imposing differential rules on Western Australian fishers was unnecessary, discriminatory and probably counter productive.

It was also agreed that as the TAC was to be set at a level designed to protect the SBT stock, it was unnecessary for management to attempt to prescribe the fishing methods used. This would best be determined by economic forces. No further restrictions were therefore placed on purse-seine boats. It was further agreed that fishers using troll-lines, long-lines, drop-lines, etc, and taking SBT as a bycatch, would be permitted to do so provided the catch-per-boat did not exceed 5 tonnes. A fisher who took more than 5 tonnes would have to acquire quota from a quota-holder. This again was a political compromise designed to satisfy the concern by some States that the measures proposed might inadvertently cause unintended disruption to the operations of relatively small-scale diversified fishers.

To be eligible to be allocated SBT quota a fisher had to meet one of the following criteria.

Those who satisfied one of the above criteria were allocated quota units on the following bases.

Under this formula fishers who qualified under criterion II or III were allocated quota on the basis of investment in the fishery only.

4. DATA REQUIREMENTS AND COMPUTATIONAL PROCESS

The compilation of data sets for the SBT fishery was relatively simple, compared to most fisheries. This was primarily because only one species was involved and although the fishery covered a wide geographic area, there were relatively few market outlets. Fish was mostly sold either to a small number (four or five) of canneries, or were exported to Japan. Very little was sold on the domestic fresh fish market. The data sources used to determine individual catch histories were therefore fishing logbooks, sales documents from canneries and export documentation (Geen, Neilander and Meany 1993).

To ensure consistency in the valuation of boats, a marine surveyor was contracted to independently assess each boat that satisfied the entry criteria. The valuation included fishing gear and navigation equipment (Geen, Neilander and Meany 1993).

5. APPEALS PROCESS

A panel of government officials, the Southern Bluefin Tuna Review Panel, was established to consider appeals over quota-allocations. The chair of this panel was an officer of the Commonwealth government. The other three panel members were officials from the South Australian, Western Australian and New South Wales fishery departments. It was agreed that no panel member could have had previous involvement in management of the SBT fishery.

The Panel visited fishing ports to allow appellants to personally present their cases. The Panel considered a total of 53 appeals in December 1984 and appellants were advised of the outcome in February 1985. As a result of the Panel's review, recommendations were made that two additional Western Australian fishers be allocated quota and that six applicants should have their quota allocation increased. The Panel's task was to consider only whether the formula for allocating quota had been properly applied in each case. It could not review the allocation formula itself.

Many of the appellants sought additional quota because they considered that their initial quota-allocation was insufficient for their commercial viability. This was not an issue that the Panel could take into consideration and was largely a result of the reduction in total catch (as represented by the TAC) rather than from the allocation formula itself. The instances where the Panel recommended additional allocations were mostly those where fishers were able to provide evidence of catches not previously considered.

Applicants who were disatisfied with outcome of the Panel's review also had the right of appeal to the Administration Appeals Tribunal (AAT).3 A total of 24 appeals were made to the AAT. Following consideration of each of these appeals the AAT approved either the allocation of quota or, the allocation of additional quota, in five cases (Geen, Neilander and Meany 1993).

6. ADMINISTRATION OF THE ALLOCATION PROCESS

6.1 Staff requirements

As previously noted an independent marine surveyor was employed to assess the boat values used in the quota-allocation formula. The use of an independent valuer was primarily to avoid any possible claim of bias that may have arisen had a person in government employment been used.

Apart from this, the personnel who undertook the project were provided from existing staff resources. To an extent this was facilitated by the fact that several governments were involved, so that the work involved was spread over a relatively large staffing base. However, the involvement of many different governments, each with slightly different regional objectives, also added to the complexity of the task.

Different staff, with different skills, were used at each stage of the implementation process. The TTF which was set up to make the initial recommendations, comprised relatively senior officers who worked part-time on this project in addition to their other responsibilities. The two-person secretariat to the TTF was, however, committed full-time to this project for its duration.

The officers who compiled the catch-histories used in the initial quota-allocation were seconded from other duties in their respective departments for the duration of their task, as were the officers who comprised the Southern Bluefin Tuna Review Panel. In view of the time that has elapsed since the initial quota-allocation was made it is not feasible now to make an estimate of the total manpower involved.

6.2 Additional programme funding requirements

Funding for this project was provided from within existing budget resources. Each of the different departments involved (state and Commonwealth) was responsible for funding its own part in this project. As none of the organisations involved were using programme-budgeting when ITQs were introduced into the Australian sector of the SBT fishery, it is impossible to identify the actual expenditure involved.

The Commonwealth government met the full cost of the marine surveyor used to value the boats, and also the cost of industry participation in the TTF. This latter payment was, however, limited to out-of-pocket expenses (travel and accommodation). Industry members of the TTF did not receive payment from government for the time devoted to this activity. It is, however, probable that some of these industry members received some compensation from their industry organisation for the time devoted to this activity.

7. EVALUATION OF THE INITIAL ALLOCATION PROCESS

7.1 Success in achieving initial policy objectives

It is difficult to differentiate between the impact of introducing ITQs into the Australian sector of the SBT fishery as an exercise in creating transferable harvesting rights, and the impact on the fishery of the TAC reductions which were happening at the same time.

At the first meeting, in February 1985, of the industry/government Southern Tuna Management Advisory Committee (to a large extent the same individuals who had been members of the TTF) it was reported that the system was working well and that there had been a significant increase in the average size of fish taken. There had also been an increase in the amount of catch sold on the Japanese sashimi market.

The Committee was also advised that 143 boats had initially been allocated quota, but that after ITQ transfers only 85 remained. A total of 6750t of quota about (46%) had been transferred. Most of these transfers were associated with intra-state transfers, which largely represented consolidation of quota-holdings. However, a significant number represented transfers to South Australian fishers from fishers in other states as Table 2 illustrates. Of particular interest was that 37% of the initial allocation to Western Australian fishers had already been transferred. It should be noted that these figures include only `permanent' transfers of quota (i.e. quota that had been sold). The table does not include seasonal transfers (i.e. leased quota), which were reportedly of similar magnitude (Anon. 1985).

Table 2

Comparison of SBT Quota holdings October 1984 and February 1985

Source: Anon. 1985

Three principal factors appear to have driven this rapid change in quota holdings:

7.2 Satisfaction of rights-holders with the process

As a general rule it is probably true that most rights-holders were disappointed with their initial allocation of SBT quota. This was because most failed to differentiate between the impact of the allocation formula itself and the reduction in the TAC that occurred at the same time. This TAC reduction, which continued after the introduction of ITQs (the TAC for the Australian sector of the fishery is now 5265t), was essential for the long-term survival of the commercial fishery. This catch reduction would inevitably have resulted in hardship for many in the fishery, irrespective of whether ITQs or some other management mechanism was used. Regardless of this, most fishers appeared to ignore the inevitable consequences of the reduction in the TAC, and tended to place all the blame for dislocation to their fishing activity that followed their introduction, on the ITQ-system.

The reduction in the TAC meant that all fishers suffered a reduction from their historic catch-levels. For some this meant having to buy additional quota to remain viable. For others, it meant having to sell quota and cease tuna fishing. It might be noted that many fishers, particularly those in New South Wales and Western Australia, were only part-time tuna fishers. The sale of tuna quota by these fishers meant that they were not forced to leave the fishing industry but could continue to fish by targeting other species.

Although tuna fishing may have been only a seasonal operation for these fishers, it did bring in vital income. In many cases the loss of this income meant that a previously marginal operation became sub-marginal. It also meant that, at least in New South Wales and Western Australia, it is likely that additional fishing pressure was placed on other fish-stocks, many of which were at, or near, full exploitation. It should be noted that this additional fishing effort would come not only from boats from which SBT quota had been sold, but also from boats that had retained their quota allocation, although because of the reduced TAC were obliged to then take less Southern bluefin tuna. This is another instance where it is not possible to separate the impact of introducing ITQs from that associated with a reduction in the TAC.

If this diversion of effort onto species in other fisheries did in fact occur, it would mean that part of the costs associated with the adjustment process were carried by fisheries other than the SBT. It would also mean that fishers, operating in those fisheries that did not have tuna quota, suffered reduced catches and loss of income because of increased fishing effort by ex-SBT fishers. This would mean that these other fisheries subsidised the adjustment in the tuna fishery. The rate of adjustment in the SBT fishery was much greater than that experienced in other fisheries when ITQs were first introduced, for example in New Zealand, or in the trawl sector of the Australian South-East Fishery. In these fisheries the rate of adjustment appeared to be much better aligned with the rate that the fishing boats became obselete.

It is also true that many fishers considered that the allocation formula was based on the wrong years. New South Wales fishers considered the allocation formula should have used a greater range of years (which would have favoured them) while Western Australian fishers would have preferred a formula biased towards the later years. All sectors of the fishery were unhappy with their quota-allocation. This dissatisfaction was not, however, necessarily related to the allocation process itself, but was the inevitable result in the concurrent reduction in the TAC.

7.3 Views of other community groups

Apart from some local concern relating to potential loss of employment, there appears to have been limited community interest in the introduction of ITQs. Even the concern about reduced employment appears to have been related more to the reduction in the TAC and its likely impact on employment in fish-canning rather than in the fishing industry itself.

Conservation groups did not appear to have realised how bad the stock situation in the fishery had become, and there is no record of their being an active party to the debate on this issue. Neither was there apparently any interest in this issue on the part of the wider public, either because of the loss of public right to enter the commercial fishery, which ceased when the fishery became limited-entry or, with respect to the public benefit associated with the establishment more secure, tradable harvesting rights.

7.4 Hind-sight assessment

Considering the rapidly deteriorating situation with SBT stocks in the early 1980s it is evident that decisive action had to be taken if a viable commercial fishery was to be maintained. This had to involve a significant reduction in total catch and a diversion of catching away from one and two year-old fish. The setting of the TAC achieved the first of these objectives, while the fortuitous circumstance of the large price differential between small and larger tuna provided the incentive for Western Australian fishers to benefit from the market and to sell much of their quota, thereby significantly reducing the catch of small fish.

The biggest problem with introducing ITQs, as it is with most significant changes to the management of any fishery, is getting a reasonably acceptable formula for making individual allocations. In the case of the SBT fishery this difficulty was compounded by the fact that the introduction of ITQs was accompanied by a TAC that represented a substantial reduction in the annual catch taken in the proceeding few years. No matter what allocation formula was chosen, the individual fishers were faced with a significant reduction from their previous levels of catch.

The fact that this is a single-species fishery, with a few well defined market outlets, made the SBT fishery well suited to the use ITQs. This applied both to the ready availability of market records on which to make the initial quota allocations and, just as important, to the monitoring of catches against quota-holdings after ITQs were introduced.

In summary, given the circumstances in this fishery and even with the benefit of perfect hind-sight, it would seem that in just about all respects the fisheries managers, in cooperation with scientists and the fishers themselves, for once got all aspects as about as right as they could have reasonably hoped, in making the transition in the method of management. It may have helped if greater attention had been paid to explaining the impact of the quota-allocation separately from the issue of TAC-reduction. It is, however, likely that most fishers would have noted only their actual quota-allocation. The detail of how this was arrived at, and the wider issues involved would probably have received limited attention.

The introduction of ITQs has certainly assisted in the further adjustments to the fishery which have resulted from subsequent TAC reductions. Fishers have now adjusted completely to the system, so that these subsequent TAC reductions were handled entirely through the market place and without the need for further intervention by managers.

8. LITERATURE CITED

Anon. Australian Fisheries 1983. 42(8) p 13. AGPS, Canberra.

Anon. Australian Fisheries 1984. 43(4): 8-9, AGPS, Canberra.

Anon. Australian Fisheries 1984. 43(9): 5-6, AGPS, Canberra.

Anon. Australian Fisheries 1985. 44(3): 2-4. AGPS, Canberra.

Campbell, D., T. Battaglene and D. Brown 1996. Use of individual transferable quotas in Australian fisheries, ABARE Conference Paper 96-21, ABARE (Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics), Canberra.

Geen, G., W. Nielander and T.F. Meany 1993. Australian Experience with Individual Transferable Quota Systems. In: The Use of Individual Quotas in Fisheries Management. OECD, Paris. pp. 73-94.

Geen, G. and M. Nayar 1989. Individual Transferable Quotas and the Southern Bluefin Tuna Fishery, ABARE Occasional Paper No 105, AGPS, Canberra.

Hampton, J. and J. Majkowski 1986. Scientists fear SBT problems worsening. Australian Fisheries 45(12):6-9.

IAC (Industries Assistance Commission) 1984. Southern Bluefin Tuna, Industries Assistance Commission Report, AGPS, Canberra.

Kailola, P., M. Williams, P. Stewart, R. Reichelt, A. McNee and C. Greive 1993. Australian Fisheries Resources, Bureau of Resource Sciences, Canberra.

Majkowski, J. and M. Caton 1984. Scientists' concerns behind tuna management. Australian Fisheries, 43(3): 371-382.

Wesney, D., B. Scott and P. Franklin 1985. Recent developments in the management of major Australian fisheries: theory and practice. In: Proceedings of the Second Conference of the Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade, Vol. 1, Christchurch, New Zealand, August 20-23 1984, pp. 289-303.

1 Note that: subsequent to the introduction of the management measures described in this paper, a legal regime called the Offshore Constitutional Settlement (OCS) was negotiated between the Commonwealth Government and the various state governments. Under this OCS, agreements can be made with respect to specific fisheries that allow either the Commonwealth or a state government to manage the fishery from low water mark to the outer edge of the AFZ. Under agreements enabled by the OCS, the Commonwealth Government now has sole responsibility for managing the SBT fishery.

2 The IAC was an expert body set up by the Commonwealth Government to advise on the need to provide assistance (subsidies, tariffs, etc.) to various sectors of the Australian economy.

3 The AAT is a general review body, set up by the Commonwealth government to consider claims relating to bias or other lack of equity in administrative decisions by Commonwealth government departments.