Lisa C. Smith

International Food Policy Research Institute

Washington, DC, USA

Executive summary

This paper explores the use of household expenditure surveys for assessing food insecurity among people in developing countries. The main objective of the paper is to lay out the background information needed for assessing the reliability, validity and practical usefulness of measures of food insecurity obtained from such surveys. From this stand-point, four main strengths of household expenditure surveys are identified. The first is that they are a source of multiple, policy- relevant and valid measures. These are: (1) household food energy deficiency; (2) dietary diversity, a measure of diet quality; and (3) the percent of expenditures on food, a measure of vulnerability to food deprivation. The second strength is that they allow multilevel monitoring and targeting. The measures can be used to calculate within-country, national, regional and developing-world prevalences of food insecurity and to monitor how these change over time. Because the food data are matched with various demographic characteristics of households, they can also be used to identify who the food insecure are. The third strength is that they allow causal analysis for identifying actions to reduce food insecurity -information that is vital to policy-makers and programme designers intending to reduce food insecurity. Finally, given that food insecurity manifests itself at household and individual levels, as the data on expenditures are collected directly from households themselves, they are likely to be more reliable than those derived from data collected at more aggregate levels. The main weaknesses of household expenditure surveys for the purposes of measuring food insecurity are: (1) they are currently not undertaken on a regular basis in all developing countries; (2) data collection and computational costs in terms of time, financial resources and technical skill required are quite high; (3) data are not collected on the access to food by individuals within households; and (4) although reasonably reliable estimates of food insecurity can be obtained, estimates may be biased owing to various systematic, non-sampling errors.

Introduction

This paper explores the use of household expenditure surveys for assessing food insecurity at the national level. Food security, the opposite of food insecurity, is defined as: "access by all people at all times to enough food for an active and healthy life "(World Bank, 1986). The main objective of the paper is to lay out the background information needed for assessing the reliability, validity and practical usefulness -for the purpose of reducing food insecurity -of measures of food insecurity obtained from household expenditure surveys. The most basic statistic on which such measures are based is "household food energy availability", which is the number of kilocalories contained in the food acquired by a household.

The main purpose of national household expenditure surveys is to evaluate the consumption and welfare of a country's population. Most surveys are specifically designed to capture the full distribution across a population (rather than simple averages) of various measures of welfare, including total income, often proxied by total expenditures, and the consumption of food and non-food items. In the past, surveys were not undertaken with the express goal of calculating household energy availability; however, many recent surveys are implemented explicitly for this purpose, whether the intention is to use the information for calculating food-based indicators of a population's well -being or for calculating poverty lines. Household expenditure surveys are very often part of wider multipurpose surveys in which data are collected on health, education and demographic characteristics of households as well as community infrastructure. Data collection and analysis methods were first documented in a publication by the United Nations (UN, 1984) as part of the UN National Household Survey Capability Program. They are further elaborated in Grosh and Glewwe (2000), drawing on the experience of the World Bank's Living Standards Measurement Survey programme.

It should be emphasized that the food data collected in household expenditure surveys reflect the quantity of food "acquired" by a household rather than that "consumed" by its members. Data on the latter are collected in household food consumption or individual dietary intake surveys.

The section "Basic data sources and reliability issues" in this paper gives details on the data collected in household expenditure surveys used to compute household energy availability. It also assesses the reliability of this measure given the data collection methods. In the section "Measures of food insecurity, their validity and cross-country comparability", the various measures of food insecurity derived from survey data are outlined, followed by an evaluation of validity of these measures and their comparability across countries. The section "Data availability and relative costs" discusses the availability of household expenditure survey data and the costs of data collection and processing in comparison with alternative types of surveys. The section "Uses of the data and potential for improvements in support for decision-making" highlights the many uses of the data in the areas of monitoring, targeting, research and evaluation. The section "Comparison with other methods" compares the household expenditure survey method with the four other methods of measuring food insecurity or undernutrition being discussed at this Symposium. Finally, the last section, "Conclusion: Summary of strengths and weaknesses", summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of using household expenditure surveys for the assessment and amelioration of food insecurity.

Basic data sources and reliability issues

The source of the information collected in nationwide household expenditure surveys is the adult women or men living in surveyed households. This is one of their main advantages. The information comes directly from the location in which behaviour regarding food consumption takes place and from the people who consume the food. The information derived at the household level reflects the food acquired and thus immediately available to the household rather than the food available to groups of households in a broader geographic area, such as a community or a country. While many types of error in data collection can occur, as discussed below, this particular aspect tends to reduce the possibility of gross errors in estimates of food insecurity that are derived from household expenditure surveys.

Systematic, scientific sampling is the norm, ensuring a nationally representative sample, i.e. full country coverage.[6] Because the sampling frames are normally taken from censuses of households, only migrants, homeless people and others living in isolated areas with poor infrastructures or in areas with violence owing to conflict are likely to be missed. Additionally, because data are collected at the household level, individuals who are food insecure but who live in food secure households cannot be identified - one of the main disadvantages of these types of surveys.

The most common method of data collection in developing countries is the personal interview, where an enumerator asks one or more household members to recall expenditures made over a reference period, usually one week, two weeks or one month. The diary method is occasionally employed. Owing to strong seasonal variation in food consumption associated with the agricultural cycle (Behrman and Deolalikar, 1989; Svedberg, 2000), data must be collected either in multiple rounds throughout a full year or in one -time interviews conducted randomly throughout a year. For the latter, seasonal effects can be imputed, and adjustments for seasonality can then be made for each household based on its particular socio -economic characteristics, such as income and location (Grootaert and Cheung, 1985; Larson, 1997).

The basic data used to construct the household food energy availability measure are either reported quantities of food[7] or reported food expenditures and prices, from which quantities can be derived. Data are collected on food acquired from three sources: (1) food purchases, including food purchased and consumed away from home; (2) food given to a household member as a gift or as payment for work; and (3) food consumed from home production. To calculate daily energy availability for a household, the quantities of each food item are first converted to kilocalorie values using conversion tables.[8] The kilocalorie values are then summed and divided by the number of days in the reference period. This figure is then divided by the number of people or adult-equivalent persons living in the household in order to assess the sufficiency of available energy to meet the dietary needs of household members (see section "Measures of food insecurity, their validity and cross-country comparability").

A number of reliability issues resulting in non-sampling errors in the measurement of household energy availability arise during the collection of household expenditure survey data. The first of these is that data are plagued by the typical reporting biases faced by all household surveys employing interview methods. These include recall errors, reporting errors, interviewer effects and "prestige errors", that is, misreporting owing to social pressures (Deaton and Grosh, 2000). A second reliability issue is that information on food purchased and consumed away from home, for example restaurant meals, is usually not reported in terms of food quantities but instead as expenditures. This obviously hampers conversion to kilocalories. The practical solution to this problem is to convert expenditures to kilocalories using kilocalorie values per unit of expenditure on foods eaten at home (e.g. PRC, 1992). However, meals eaten outside the home may consist of different kinds of foods with different kilocalorie values compared with meals eaten at home. Further, the relative energy density of in-home and out-of-home food consumed may differ across income groups, again leading to systematically biased estimates.[9]

Two aspects of data collection inherent to survey designs create discrepancies between a household's acquisition of food over the recall period and the consumption of food by the household over the recall period. These represent reliability issues only if the intent is to measure food energy intakes as opposed to availability. The first aspect is that the food consumed by guests and hired workers, given to pets and wasted is not recorded, leading to an upward bias in estimates of energy in- takes. Because the quantity of food used in these three ways is usually greater for richer households, the resulting difference between energy availability and intakes is systematically correlated with income (Bouis, Haddad and Kennedy, 1992; Bouis, 1994; Dowler and Seo, 1985; Naiken, 1998). The second aspect is the problem of periodicity of expenditures on different food items. Households may consume a food during the recall period (meaning that the food was definitely available) but not report it as an expenditure because the item was purchased prior to the period. This can happen, for example, if a grain product such as rice is purchased in bulk and stored. Equally likely, households may purchase and report certain items available during the recall period that will be consumed beyond that period. The first aspect leads to an underestimate of household energy availability relative to consumption, and the second leads to an overestimate. Although food expenditures (as opposed to non-food expenditures) are considered to be the least plagued by this problem, it is more likely to occur for shorter recall periods and in the case of specific or unusual food categories (Andersson and Senauer, 1994; Deaton and Irish, 1984; Deaton and Grosh, 2000). Although the periodicity problem is an issue when one is attempting to capture energy intakes at the household level, the "error" is random at the population or population group level.

While the measurement errors resulting from these reliability issues cannot be eliminated, bias in estimates of household energy availability can be reduced during data cleaning and processing and by survey design. In the cleaning stage, major outliers resulting from errors can be detected by thoroughly examining the data at the level of individual food items (Deaton and Grosh, 2000; Hentschel and Lanjouw, 1996). Suspect cases can also be identified using regression techniques that control for household characteristics (added -variable plots) (Stata, 2000). Further, scatter diagrams comparing energy availability with requirements as well as consistency checks using knowledge about human food consumption capacities can be employed.[10] Suspected erroneous values can be replaced with imputed values based on household characteristics, preferably at the level of individual food quantities (rather than total kilocalories). At the data processing stage, the bias in estimates resulting from the periodicity problem may be reduced using adjustment factors calculated from data on subsamples of households with similar characteristics.[11] Statistical techniques are available for determining whether zero expenditures result from true economic non -consumption of a food item or are random (Blissard and Blaylock, 1993; Chern and Senauer, 1993; Perali and Cox, 1995). Adjustments to the energy values applied to food eaten away from home can be made using estimates of the relative energy density of in -home and out-of-home consumed food derived from food consumption surveys, where they are available.

Finally, there are many ways in which surveys can be designed to increase the reliability of estimates of household energy availability, including longer recall periods and multiple rounds. However, these obviously involve trade -offs in recall error (for the former) and survey costs (for the latter). To overcome the periodicity problem, respondents can be asked first whether or not a food item was consumed over the reference period and then what were the expenditures for the item, as was done in the Indonesian Survei Sosial Ekonomi Nasional (SUSENAS) surveys. Additionally, specific questions can be included about consumption by non- household members and pets. For food eaten away from home, it is important to gather information on the types and quantities of foods consumed (perhaps aided by showing respondents pictures of dishes or meal portions of varying sizes) for each household member who has eaten out over the recall period. Complementary information on the energy composition of multiple -food dishes would need to be collected at the preparation source.

Measures of food insecurity, their validity and cross- country comparability

Measures

Measures

A number of measures of food insecurity can be constructed from the data collected in household expenditure surveys. Four key measures are:

household food energy deficiency;

depth of energy deficiency;

diet diversity;

percent of total expenditures on food.

This section shows how the measures are calculated and discusses their validity as measures of food insecurity. It also addresses their comparability across countries given non-uniform data collection techniques.

The most widely employed measure of those listed above is "household food energy deficiency", a dummy variable (0, 1) indicating whether a household falls below a certain energy intake requirement. Specifically, a household's energy availability is compared with a requirement that is based on its age and sex composition. Summarized for a population group, the household data give the percent of households or individuals[12] who are energy-deficient. The depth of energy deficiency (by how many kilocalories a household falls below its requirements) can also be computed. This number gives a sense of the severity of food insecurity in households categorized as "food insecure ".

The correct energy requirement is the subject of much debate because any individual's energy need is based not only on age and sex but also on body weight, body composition, disease state, genetic traits, pregnancy and lactation status and activity level (Hoddinott, 2001; Svedberg, 2000). Because data on these characteristics are not generally collected in household expenditure surveys, in practice daily energy intakes by age and sex group recommended by the WHO (1985) or other country health agencies are employed. These requirements are based on normatively specified minimum energy consumption levels given a minimum acceptable body weight for healthy people of each age and sex group. For adults, they are given for three physical activity levels: light, moderate and heavy. The requirements for each household member are summed to derive the energy requirement for the household.[13] Appendix C gives the WHO requirements for the light and moderate activity levels. Energy deficiency measures are often based on requirements for the light physical activity level. What is being evaluated is whether a household has acquired enough food over the recall period to allow all of its members to survive, even if engaging in only minimal physical activity. While the WHO requirements do not, of course, capture the energy needs of each individual person, they do provide a normative basis for judgement that is applicable to all human populations and thus comparable across countries and regions within countries.

Validity issues

Validity issues

With respect to the validity of the household energy deficiency measure, conceptually how close is it to the definition of food (in) security given in the introduction to this paper? Is this measure conceptually distinct from the major factors that determine it and that it determines? To judge such "content validity "(Trochim, 2001) requires not only a firm definition of food security but also a strong conceptual framework for it.

Figure 1 illustrates a widely agreed upon conceptual framework for food security. It shows how national food availability works through food security ultimately to influence nutritional security, i.e. adequate nutritional status on a sustainable basis. In order for households to have access to food, it is necessary that there be enough food available at the national level. However, availability at the national level is not sufficient to guarantee access at the household level. Households must also have the necessary resources to acquire that food and at the same time meet other basic needs. Finally, food security works through people's dietary intakes to influence their nutritional security. But food security is not sufficient for them to achieve nutritional security. They also need adequate care[14] and a healthy living environment to be able to absorb the nutrients in food and thus use it in their everyday lives.

As a measure of food insecurity, household energy deficiency is closely related to the notion of access to food. It measures whether a household acquires sufficient food over the recall period to meet its requirements for a major macronutrient -energy. It is clearly distinct from related concepts. It is obviously distinct from national (or even local) food availability, which is one of its determinants. It is also distinct from measures of household resource holdings, such as poverty, because these measures capture households' abilities to meet all of their needs, not just food. Finally, household energy deficiency is distinct from nutrition security, which it does determine, but not alone. Thus, from a conceptual standpoint, the basic measure derived from household expenditure surveys is a "good" measure of food insecurity.

FIGURE 1. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR FOOD SECURITY

Source: Adapted from UNICEF (1990) and Frankenberger et al. (1997)

However, the household energy deficiency measure is focused only on the current state of food deprivation. On its own, it does not capture an important component of the definition of food security, that is, vulnerability to food deprivation in the future (Maxwell and Frankenberger, 1992). One good measure of this type of vulnerability is the percent of a household's total expenditures on food. Households that spend high proportions of their incomes on food (e.g. 70 percent or more) are vulnerable because if their income is reduced, for example owing to a job loss, natural disaster, disease onset (e.g. HIV/AIDS) or price policy reform, they will have limited reserve for meeting their food needs (Maxwell and Frankenberger, 1992). This measure is easily calculated from data obtained from household expenditure surveys.[15]

|

TABLE 1. COMPARISON OF DAILY PER CAPITA ENERGY AVAILABILITY AND INTAKE FOR SUBNATIONAL SAMPLES FROM KENYA, THE PHILIPPINES AND BANGLADESH |

||||

|

Per capita total expenditure (quartile) |

Energy availability (kcal) |

Energy intake (kcal) |

Percentage difference |

Number of households |

|

Kenya 1985 87 |

||||

|

1 |

1 441 |

1 706 |

-15.5 |

289 |

|

2 |

1 759 |

1 948 |

-9.7 |

292 |

|

3 |

2 043 |

2 026 |

0.84 |

289 |

|

4 |

2 293 |

2 232 |

2.7 |

291 |

|

All |

1 884 |

1 978 |

-4.6 |

1 161 |

|

Philippines 1984 85 |

||||

|

1 |

1 385 |

1 726 |

-19.8 |

448 |

|

2 |

1 684 |

1 877 |

-10.3 |

448 |

|

3 |

2 029 |

2 035 |

-0.29 |

448 |

|

4 |

2 540 |

2 196 |

15.7 |

448 |

|

All |

1 909 |

1 959 |

-2.6 |

1 792 |

|

Bangladesh 1995 96 |

||||

|

1 |

1 819 |

2 101 |

-13.7 |

236 |

|

2 |

2 164 |

2 270 |

-4.4 |

236 |

|

3 |

2 471 |

2 346 |

4.6 |

236 |

|

4 |

2 801 |

2 423 |

16.2 |

235 |

|

All |

2 313 |

2 285 |

1.2 |

943 |

|

Sources: Bouis, Haddad and Kennedy (1992), table 1 for Kenya and the Philippines. The numbers for Bangladesh are calculated by the author from raw data collected under the "Commercial Vegetable and Polyculture Fish Production in Bangladesh" project ((Bouis et al., 1998). |

||||

Energy is not the only nutrient that people need to lead active, healthy lives. It is quite possible for a person to meet their energy requirement but to be prevented from achieving full physical and intellectual potential because of deficiencies of other nutrients, such as iron, vitamin A and iodine. Recent studies show that the consumption of animal and fish products is more highly correlated with measures of nutritional status than total energy or energy consumed from starches - the source of the large majority of total energy consumed (Bouis, 1999, 2000; Bouis and Hunt, 1999; Hoddinott and Yohannes, 2002). Simple tabulations of the types of foods a country's population consumes reveal much about dietary quality. Diet diversity - the number of different foods or food groups consumed by a household - is considered to be a good summary measure of diet quality (Hoddinott and Yohannes, 2002; Ruel, 2002). An indicator of this, the number of foods or food groups acquired, can also be easily calculated from data collected in household expenditure surveys. This discussion shows that household energy deficiency based on a measure of household energy availability has strong concept validity when combined with the percent of expenditures on food and diet diversity, the data for which are routinely collected as part of household expenditure surveys.

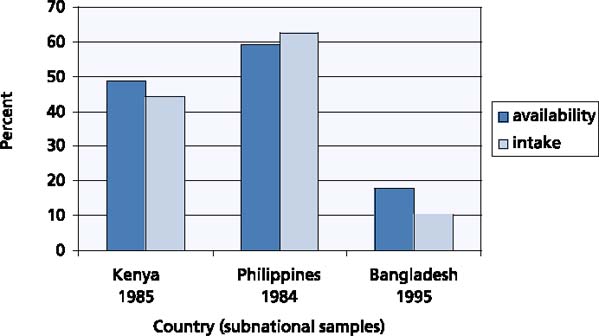

FIGURE 2. COMPARISON OF THE PERCENT OF FOOD ENERGY DEFICIENT HOUSEHOLDS ESTIMATED USING ENERGY AVAILABILITY AND INTAKE DATA FROM KENYA, PHILIPPINES AND BANGLADESH (SUB-NATIONAL SAMPLES)

The percentage energy deficient is calculated using household-level data on energy availability and intakes per capita together with regional minimum energy requirements repor ted in FA0 (1996), Table 16. The Kcal cutof fs employed are 1800 for Kenya, 1880 for Philippines and 1790 for Bangladesh.

Source: See source list for Table 1.

Another type of validity, "predictive validity", addresses how well a variable predicts another variable that it should theoretically be able to predict (Trochim, 2001). One such variable that the household energy availability measure should be able to predict is household energy "intakes "-the sum of the kilocalories in the food consumed by individual household members, as collected in food consumption surveys. It should be able to do so because although not all of the energy acquired by a household is consumed by its members (owing to waste, feeding of food to pets and guests, and stores for consumption after the period, mentioned in the section "Basic data sources and reliability issues"), we expect that much of it is. To judge the predictive validity of the household energy availability measure, Table 1 compares means of daily per capita energy availability and daily per capita energy intake from three of the few surveys ever conducted in which both were collected from the same households. These surveys, conducted by the International Food Policy Research Institute in Kenya, Philippines and Bangladesh were subnational and, for Kenya and the Philippines, administered to relatively poor populations within the countries. For all three surveys, the overall means of energy intakes and availability are very close, the greatest percent difference being for Kenya where energy availability is 4.6 percent lower than intakes. The very small differences between the availability and intake -based measures confirm a strong predictive validity. They also provide evidence in support of the reliability of the household energy availability measure for evaluating energy deficiency at the population level in spite of the reliability issues raised in the section "Basic data sources and reliability issues". Figure 2 shows the percent of energy-deficient households for each sample.

It should be noted that the differences between the availability and intake measures are greater when considering individual total expenditure quartiles. The highest percent differences are for the poorest (negative percent difference) and richest (positive percent difference) quartiles. This finding is not surprising because, as pointed out in Bouis, Haddad and Kennedy (1992), the numbers of guests (and possibly workers) sharing in the consumption of food is the lowest for the poorest households and highest for the richest, causing discrepancies between availability and actual consumption. For those attempting to capture household food consumption rather than food availability, these differences need to be acknowledged when energy availability is being related to income at the household level, for example when undertaking regression or correlation analysis.

To summarize, household expenditure surveys are a rich source of valid measures of food insecurity. Optimally, all three measures discussed here - household energy deficiency, degree of vulnerability to future food insecurity and diet quality - should be triangulated. We can be surer that a population group that has a high prevalence of energy deficiency, spends a high proportion of its income on food and on average eats only ten different foods over the course of a week is food insecure than if we know only its prevalence of energy deficiency.

Cross-country comparability

Cross-country comparability

Data are generally not collected using the same methods in every country where household expenditure surveys are conducted. However, because the same basic data are collected, the derived food insecurity measures are largely comparable across countries if data cleaning, processing and computation methods are standardized. To give an idea of the variation in methods employed, Table 2 gives some specific examples of the data collection methods for selected surveys in Sub -Saharan Africa in the 1990s. Because of differences in survey duration, number of visits, recall periods and the identity and numbers of food groups, certain harmonization processes must take place to make the computed measures comparable. The experience of the Datafood Networking (DAFNE) projects is informative on this matter. The projects (DAFNE I and DAFNE II, funded by the EU) have researched the feasibility of creating a pan-European food data bank based on household expenditure survey data. Their results to date demonstrate that a number of harmonization issues can be overcome with common aggregation rules and judicious use of secondary data (Lagiou et al., 2001).

|

TABLE 2. INFORMATION ON A SELECTED LIST OF NATIONALLY REPRESENTATIVE HOUSEHOLD EXPENDITURE SURVEYS FROM SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA, 1990 - 2000 |

||||||

|

Country |

Year of survey |

Number of households |

Duration of survey (months) |

Recall period |

Number of visitsa |

Number of food items |

|

Burkina Faso |

1998 |

8 500 |

4 |

2 weeks |

1 |

32 |

|

Burundi |

1998 |

6 668 |

6 |

2 weeks |

1 |

32 |

|

Ivory Coast |

1998 |

4 200 |

11 |

1 week |

1 |

29 |

|

Ethiopia |

1995 |

11 687 |

7 |

3-4 days |

16 |

200 |

|

Gambia |

1992 |

1 400 |

5 |

2 weeks |

1 |

50 |

|

Ghana |

1998 |

5 998 |

12 |

5 days |

6 |

97 |

|

Guinea |

1994 |

4 705 |

12 |

3 days |

10 |

116 |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

1993 |

3 300 |

12 |

1 week |

7 |

255 |

|

Kenya |

1997 |

12 000 |

12 |

1 week |

1 |

79 |

|

Malawi |

1997 |

10 968 |

12 |

3-4 days |

4-8b |

405 |

|

Mozambique |

1996 |

8 000 |

15 |

7 days |

1 |

200 |

|

South Africa |

1993 |

9 000 |

10 |

1 week or 1 month |

1 |

31 |

|

Swaziland |

1995 |

6 350 |

12 |

1 week |

1 |

102 |

|

Uganda |

1999 |

10 700 |

12 |

1 week |

1 |

59 |

|

Zambia |

1996 |

11 800 |

2 |

2 weeks |

1 |

31 |

|

a The number of visits refers to the number of

times households were asked to report on food acquisition. |

||||||

In the long term, cross-country comparability could be enhanced with a standardization of survey design. However, it may be unwise to force all surveys into one mode, ignoring country-level specifics relating to food consumption patterns, degree of market integration and survey implementation capacities. Haddad (2001) suggests ways that comparability can be improved through standard protocols for collection of survey data. An International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) /FAO/World Bank collaborative project "Improving the Empirical Basis for Assessing Food Insecurity in Developing Countries" (the AFINS project) is working to develop guidelines for data collection, cleaning and processing that, if widely adopted, will improve cross-country comparability.

Data availability and relative costs

While nationally representative household expenditure surveys were rare before 1970, and many were of dubious quality even into the 1980s (von Braun and Puetz, 1993; Svedberg, 2000), since 1980 a number of major international programmes have been organized to support the collection of household survey data in developing countries. A surge in the availability of household expenditure surveys has taken place, and the quality of surveys has increased greatly.

Data on household expenditures are routinely collected as part of the World Bank's Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) survey programme and two regional survey programmes that grew out of it, the Social Dimensions of Adjustment programme for sub -Saharan Africa and the Programa de Mejoramiento de las Encuestas de Condiciones de Vida (MECOVI) programme for Latin America (Grosh and Glewwe, 2000). Further, a number of developing country governments carry out household expenditure surveys on a regular basis, for example, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia and the Philippines. While the Demographic and Health Survey project (DHS, 2001), with major funding from the United States Agency for International Development, has traditionally only collected data on health, nutritional status and demographic variables, experiments are now under way to include household expenditure data (e.g. the Dominican Republic 1999 Survey). Data accessibility has been improved as well. The LSMS programme posts data from some of its surveys on the Internet. Additionally, a large number of datasets collected by African government statistical services are deposited with the World Bank's Africa Household Survey Databank and can be made available for use, with government permission.

Table 3 lists some of the nationally representative household expenditure surveys undertaken in the 1990s. The IFPRI /FAO/World Bank AFINS project is currently in the process of locating and evaluating the quality of the available datasets. So far, this evaluation has been undertaken only for sub -Saharan African countries. Datasets collected in the 1990s that are suitable for computing the household energy availability measure are available for approximately 20 countries in the region (50 percent).

|

TABLE 3. NATIONALLY REPRESENTATIVE HOUSEHOLD SURVEYS CONTAINING FOOD EXPENDITURE DATA (1990 - 2000) |

|||

|

Region/country |

Year |

Sample size |

Type |

|

SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA |

|||

|

Burkina Faso |

1998 |

8 478 |

World Bank PS |

|

Burundi |

1998 |

6 668 |

World Bank PS |

|

Cameroon |

1996 |

1 710 |

World Bank PS |

|

Central African Republic |

1995 |

4 500 |

Government HES |

|

Comoros |

1995 |

2 004 |

Government HES |

|

Ivory Coast |

1995 |

1 200 |

World Bank PS |

|

Djibouti |

1996 |

2 400 |

World Bank PS |

|

Eritrea |

1997 |

naa |

World Bank PS |

|

Ethiopia |

1998 |

16 000 |

World bank PS |

|

Gambia |

1994 |

2 000 |

World Bank PS |

|

Ghana |

1998 |

5 998 |

World Bank |

|

Guinea |

1994 |

4 705 |

Government HES |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

1993 |

3 300 |

Government HES |

|

Kenya |

1997 |

12 000 |

World Bank PS |

|

Lesotho |

1995 |

11 770 |

Government HES |

|

Madagascar |

1997 |

6 350 |

World Bank PS |

|

Malawi |

1997 |

10 698 |

Government HES |

|

Mali |

1994 |

9 700 |

World Bank PS |

|

Mauritania |

1995 |

3 540 |

Government HES |

|

Mauritius |

1991 |

5 712 |

Government HES |

|

Mozambique |

1996 |

8 000 |

Government HES |

|

Namibia |

1993 |

4 750 |

Government HES |

|

Niger |

1995 |

4 383 |

Government HES |

|

Nigeria |

1996 |

12 000 |

Government HES |

|

Rwanda |

1998 |

na |

World Bank |

|

Senegal |

1994 |

3 277 |

Government HES |

|

Sierra Leone |

1994 |

na |

World Bank |

|

South Africa |

1993 |

9 000 |

World Bank |

|

Swaziland |

1995 |

6 350 |

Government HES |

|

Tanzania |

1993 |

4 953 |

World Bank |

|

Uganda |

1995 |

5 000 |

World Bank PS |

|

Zambia |

1998 |

16 636 |

World Bank PS |

|

Zimbabwe |

1995 |

na |

Government HES |

|

SOUTH SIA |

|||

|

Bangladesh |

1996 |

7 440 |

Government HES |

|

India |

1997 |

25 000 |

Government HES |

|

Nepal |

1995 |

3 388 |

World Bank |

|

Pakistan |

1996 |

12 500 |

World Bank |

|

Sri Lanka |

1996 |

21 220 |

Government HES |

|

EAST SIA |

|||

|

Cambodia |

1999 |

6 000 |

World Bank LSMS |

|

China |

1999 |

100 000 |

Government HES |

|

Indonesia |

1999 |

205 000 |

Government HES |

|

South Korea |

1996 |

30 000 |

Government HES |

|

Laos |

1998 |

8 882 |

Government HES |

|

Malaysia |

1999 |

na |

World Bank LSMS |

|

Mongolia |

1996 |

1 500 |

Government HES |

|

Myanmar |

1997 |

25 470 |

Government HES |

|

Papua New Guinea |

1997 |

1 146 |

World Bank |

|

Philippines |

1997 |

41 000 |

Government HES |

|

Thailand |

1998 |

na |

Government HES |

|

Viet Nam |

1998 |

6 000 |

World Bank LSMS |

|

NEAR EAST AND NORTH AFRICA |

|||

|

Algeria |

1995 |

5 910 |

Government HES |

|

Egypt |

1999 |

na |

Government HES |

|

Jordan |

1997 |

6 048 |

Government HES |

|

Iran |

1995 |

4 000 |

Government HES |

|

Kuwait |

1999 |

5 000 |

Government HES |

|

Lebanon |

1997 |

na |

Government HES |

|

Morocco |

1998 |

5 184 |

Government HES |

|

Oman |

1998 |

na |

Government HES |

|

Tunisia |

1996 |

3 400 |

World Bank LSMS |

|

West Bank and Gaza |

1997 |

3 600 |

Government HES |

|

Yemen |

1998 |

15 120 |

Government HES |

|

LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN |

|||

|

Belize |

1996 |

na |

Government HES |

|

Brazil |

1999 |

na |

Government HES |

|

Costa Rica |

1992 |

2 490 |

Government HES |

|

Dominican Republic |

1998 |

na |

Government HES |

|

Ecuador |

1999 |

na |

World Bank LSMS |

|

El Salvador |

1998 |

12 375 |

Government HES |

|

Guatemala |

2000 |

na |

World Bank LSMS |

|

Guyana |

1999 |

9 276 |

World Bank LSMS |

|

Jamaica |

1998 |

7 375 |

World Bank LSMS |

|

Mexico |

1996 |

11 000 |

Government HES |

|

Nicaragua |

1998 |

4 209 |

World Bank LSMS |

|

Paraguay |

1997 |

4 353 |

Government HES |

|

Panama |

1998 |

5 614 |

Government HES |

|

Peru |

1999 |

na |

World Bank LSMS |

|

Trinidad and Tobago |

1998 |

1 500 |

Government HES |

|

PS: Priority Survey; HES: Household Expenditure Survey; LSMS:

Living Standards Measurement Survey. |

|||

In terms of costs, household expenditure surveys are quite time -and skill -intensive. While the data collection is fairly straightforward, a large amount of data must be collected and entered into a database. Processing the data requires much skill on the analyst's part, with great attention to detail and some knowledge of data cleaning techniques as well as of plausible values of raw data points and aggregates. On the other hand, the alternative method of collecting household data for use in creating food-based indicators of food insecurity -surveys of individual food intakes -is far more time and skill intensive (Hoddinott, 2001; Obrien-Place and Frankenberger, 1988).

Uses of the data and potential for improvements in support for decision-making

Food -related data collec ted in household expenditure surveys can be used for a wide variety of purposes that respond to the information needs of policy-makers, of which only a few of the main ones are covered here. Obrien -Place and Frankenberger (1988) and UN (1984) contain more detailed listings. First, the data can be used for reliably estimating within -country, national, regional and developing -worldwide prevalences of food insecurity and for monitoring how these change over time. This information can al so be used for targeting geographic areas of high food insecurity and for tracking progress towards food security goal s.

With regard to within -country estimates, by using the household -level data it is possible to calculate summary statistics of all of the measures discussed in the previous section for political and administrative areas of countries as well as agro -ecological zones.[16] These can be used for food insecurity mapping. Appendix A gives an example of this use for Mozambique employing its 1996 -97 survey "Mozambique Inquérito Nacional aos Agregados Familiares Sobre As Condições de Vida". Another example from the Bangladesh Household Expenditure Surveys of 1991/92 and 1995/96 shows how data from household expenditure surveys can be used to assess the nutritional quality of a population's diet and how it changes over time. The data on household energy availability in food expenditure surveys are also widely used to construct food -based poverty lines employed in mapping poverty.

With regard to regional and global estimates, the experience of the World Bank's Poverty Monitoring Project shows that multiple nationally representative household expenditure survey datasets can be used to calculate estimates of poverty (income insufficiency) at these levels as well - even in the absence of survey data from all countries. For example, the datasets included in the project have been used to estimate that in 1993, 43 percent of households were in poverty in South Asia, 26 percent in East Asia, and 39 percent in sub -Saharan Africa (Ravallion and Chen, 1996).[17] It is possible to calculate percentages in the same manner for food energy deficiency. Appendix B describest wo techniques for doing so that rely on the use of country-level secondary data for prediction purposes. Similar methods can be extended to measures of vulnerability and diet quality. Chen and Ravallion (2000) show how changes over time can be estimated. Broca and Oram (1991) provide an example of an early attempt to match data on food expenditures from multiple countries with data on agro -ecological zones in order to estimate where food insecure people live. Research on the feasibility of estimating regional and global prevalences of food insecurity using household expenditure survey data is currently ongoing as part of the AFINS project (mentioned in the last section).

The second major use of the food data collected in household expenditure surveys is to identify who is food insecure among a country's population. Because data on food expenditures are matched with data on various demographic and socio -economic characteristics of households, it is possible to identify food insecure groups of people and use this information for targeting purposes. Examples of such groups are female -headed households and households engaged in different economic activities.

Perhaps the main advantage of household expenditure surveys is that they can be used to conduct research on the causes of food insecurity. The food data in the surveys are automatically linked to data on economic status (total expenditures and often also income and asset holdings), on prices paid by households for every good and service they purchase, on education and on many other household characteristics. Information on the causes of food insecurity gained from these data can be used by policy-makers to identify effective actions for reducing it. It has been is a longstanding tradition in economics to estimate energy -income elasticities (often using total expenditures as a proxy) in order to judge the efficacy of raising incomes to improve food security (see Skoufias, 2001 for a recent study from Indonesia). Other studies look more generally at the determinants of household energy availability, such as the roles of education, household composition and seasonality (see, for example, Garrett and Ruel, 1999 and Maxwell et al., 2000 using urban samples).

When appropriate questions are included in a survey, evaluation of the impact of national policies on food security can be undertaken. Example 3 in Appendix A highlights an evaluation of the impact of a nationwide social programme on household energy availability and dietary diversity in Mexico. Illustrative subnational studies from Rwanda, Kenya, Gambia, the Philippines and Guatemala show how the impact of agricultural commercialization on household energy availability can be evaluated (von Braun and Kennedy, 1994). Household expenditure surveys can also be used to evaluate the impact of natural disasters such as floods (e.g. del Ninno et al., 2001) and financial crises (e.g. Skoufias, 2001).

An important means through which support for policy and programme decision-making can be improved is by complementing measures of food insecurity derived from household expenditure surveys with those from other sources on the determinants of food insecurity and on its ultimate outcome, the nutritional well -being of people. For example, data on national and local area food availability and on the means that households employ to maintain (or not) their livelihood security are important for developing strategies to improve food security. By complementing food insecurity data with anthropometric measures of nutritional status (such as weight-for-age, height-for-age and weight-per-height), it is possible to determine whether improvements in food security actually lead to improvements in people's nutritional status, the ultimate goal of any food security intervention.

FIGURE 3. METHODS OF MEASUREMENT OF FOOD ENERGY DEFICIENCY, FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION

Comparison with other methods

Figure 3 lists the other methods of food deprivation and undernutrition being discussed at this Symposium and the outcomes they measure. The figure helps to understand how the methods complement each other. The three outcomes are food energy deficiency, food insecurity and undernutrition.

Three of the methods are suited to measuring energy deficiency: the dietary energy supply-based method currently employed by FAO (see paper by Naiken in this series),[18] the household expenditure survey (HES) method and the individual food intake survey method (see paper by Ferro-Luzzi in this series). Because all of these attempt to measure the same outcome, the methods are substitutes for one another. Alternatively, they could play complementary roles for testing the reliability of the methods and for verifying whether identified patterns are similar across methods, thus giving more (or less) confidence in the observed results.

A second set of three methods is suitable for measuring food insecurity: the HES method, the individual food intake method and the qualitative methods (see paper by Kennedy in this series). While food intake surveys are mostly used to measure energy deficiency and diet quality aspects of food insecurity, if the proper data are collected, they can also be used to measure vulnerability. Again, these three methods are substitutes for one another since they all intend to measure the same outcomes, but can also be seen as complements for reliability testing and pattern verification purposes.

|

TABLE 4. STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF FOUR METHODS USED TO MEASURE FOOD SECURITY IN RELATION TO THE HOUSEHOLD EXPENDITURE SURVEY (HES) METHOD |

||

|

METHOD |

STRENGTHS RELATIVE TO HES METHOD |

WEAKNESSES RELATIVE TO HES METHOD |

|

Dietary energy supply-based (current FAO method) |

|

|

|

Individual food intake |

|

|

|

Anthropometry |

|

|

|

Qualitative methods |

|

|

The anthropometry method (see paper by Shetty in this series) is complementary to but not interchangeable with the other methods. It is intended to measure undernutrition, an outcome that is conceptually distinct from the other two outcomes. As noted in the previous section, it is important for understanding whether reductions in energy deficiency or food insecurity actually result in improvements in human physical well -being.

Table 4 compares the strengths and weaknesses of the four other methods used to measure food security in relation to the household expenditure survey method. In this sense, the main strength of the dietary energy supply (DES) -based method is that it allows frequently updated comparisons of energy deficiency across countries and over time. As such, it is a powerful advocacy tool. However, because of the unreliability of the underlying data on DES and the distribution of dietary energy consumption across populations within a country, comparisons across countries and over time are of unknown reliability. The reliability of the DES method is further hampered by its limited ability to capture access to food. Owing to a methodological bias in favour of national food availability, it cannot be used to understand the causes of food insecurity. Further, it is less useful as a policy and action tool because it cannot be employed to estimate energy deficiency at subnational levels and to identify the deficient groups. Finally, since it does not capture diet quality and vulnerability, it is not a complete measure of food insecurity. Note that it is difficult to judge the relative costs, in terms of time and financial resources, of the HES and DES -based methods. Both ultimately rely on the collection, processing and analysis of household expenditure surveys, which are quite costly and skill -intensive. However, the DES -based method can be (and is) applied without frequent updating of the data used from household surveys, which saves a great deal of time. Additionally, the DES -based method requires collection of food balance sheet data. Once the underlying food balance sheet and distribution data are available, the computational costs for the DES -based method are very low.

Compared with the HES method, the individual food intake method yields a more reliable measure of energy deficiency at individual and household levels because it is based on actual food consumption rather than food acquisition. Further, since the data are collected at the level of the individual human being, comparisons can be made across age and sex groups, and inequalities in intrahousehold food distribution can be identified. However, collection and processing costs for these data are considerably higher than for the data collected in HESs. For this reason, implementation of the individual food intake survey method at the country level is generally not feasible, therefore limiting the use of this method for cross-country comparisons.

The anthropometric method has several advantages. The data are less costly to collect and process, comparisons over countries and time are facilitated by standardized collection techniques, and data are collected at the individual level, thus allowing comparisons across age and sex groups. Its main disadvantage is that the outcome measure, undernutrition, is not a valid indicator of food insecurity. One of the reasons for this is that undernutrition is determined by the care that individuals receive and the health environment in which they live, and not only by food security, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

The qualitative methods have several advantages over the HES method. One is that the data are less costly to collect and process. Another is that the measures developed are focused more directly on food insecurity since people are explicitly asked about their food security status, including dimensions of sufficiency, quality and vulnerability. The HES method, by contrast, can only infer that status from indirect measures. Cutoff points used to establish whether a household is food secure or not are easier to establish and more intuitive using qualitative methods. Further, the methods reveal the human side of food insecurity by gathering information on the perceptions of those actually affected by it. With respect to reliability, while further research is needed, qualitative methods have the advantage of allowing longer recall periods but the disadvantage that, owing to the subjective nature of questions asked, they may be more susceptible to misreporting. A main weakness of qualitative methods relative to the HES method is that cross-country comparisons are difficult to make, owing to the inherent need to adapt surveys to local circumstances. Another is that the costs of development of measures for each new setting are very high.

Conclusion: Summary of strengths and weaknesses

The strengths and weaknesses of the use of HESs for the measurement of food insecurity can be summed up as follows.

Strengths

Strengths

THEY ARE A SOURCE OF MULTIPLE, POLICY-RELEVANT AND VALID MEASURES. The data collected in household expenditure surveys allow computation of a number of food insecurity measures of interest to policy-makers, including food energy deficiency, poor diet quality and vulnerability to food deprivation. These measures are solidly founded on the notion of insufficient access to food for an active and healthy life and are thus valid measures of food insecurity.

THEY ALLOW MULTILEVEL MONITORING AND TARGETING. Measures derived from the surveys can potentially be used to calculate within-country, national, regional and developing-world wide prevalences of food insecurity for targeting food insecure people and monitoring changes over time. Additionally, they can be used to identify demographic groups that are food insecure for intervention purposes.

THEY ALLOW CAUSAL ANALYSIS FOR IDENTIFYING ACTIONS TO REDUCE FOOD INSECURITY. The measures of food insecurity collected in the surveys are matched with data on many of the determinants of food insecurity. Information gained from the analysis of the relative importance of these determinants can be used by policy- makers to devise appropriate strategies for reducing food insecurity.

RELIABLE MEASUREMENT. Because the basic data are collected from households themselves, rather than at a more aggregate level, estimates of food insecurity are likely to be reasonably reliable.

Weaknesses

Weaknesses

DATA ARE NOT COLLECTED FOR ALL COUNTRIES REGULARLY. Although availability has increased, household expenditure surveys are not collected on a regular basis in all countries.

MODERATELY HIGH COLLECTION AND PROCESSING COSTS. Data collection and computational costs in terms of time, financial resources and necessary technical skill are quite high.

INTRAHOUSEHOLD FOOD DISTRIBUTION IS NOT ACCOUNTED FOR. The data do not measure the access to food of individuals within households.

RELIABILITY PROBLEMS MAY LEAD TO MEASUREMENT ERROR. While reasonably reliable estimates of food insecurity can be obtained at the population level, household-level estimates may be biased owing to various non-sampling errors.

References

Andersson, M. & Senauer. B. 1994. Non-purchasing households in food expenditure surveys: an analysis for potatoes in Sweden. Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics Staff Paper P94 -4, College of Agriculture. Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. 1998. Report on the household expenditure survey 1995 -96. Dhaka, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Ministry of Planning, Statistics Division.

Behrman, J.R. & Deolalikar, A.B. 1989. Seasonal demands for nutrient intakes and health status in rural south India. In D.E. Sahn, ed. Seasonal variability in third world agriculture: the consequences for food security, pp. 66 -78. Baltimore, MD, The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Blissard, N. & Blaylock, J. 1993. Distinguishing between market participation and infrequency of purchase models of butter demand. Am. J. Agric. Econ., 75(2): 314 -320.

Bouis, H. 1994. The effect of income on demand for food in poor countries: are our food consumption databases giving us reliable estimates? J. Dev. Econ., 44(1): 199 -226.

Bouis, H. 1999. Demand for non-staple foods and the role of micronutrients in improving nutrition: an analysis for Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam. Paper presented at the Indochinese Symposium on Globalization, Hanoi, Viet Nam.

Bouis, H. 2000. Development of modern varieties of rice: impacts of food security and poverty. Paper prepared for presentation at the International Rice Research Conference held at IRRI, Los Banos, Philippines, March 31 -April 3. Dhaka, International Rice Research Institute.

Bouis, H., Haddad L. & Kennedy, E. 1992. Does it matter how we survey demand for food? Evidence from Kenya and the Philippines. Food Policy, 17: 349 -360.

Bouis, H., de la Briere, B., Buitierrez, L., Hallman, K., Hassan, N., Hels, O., Quadbili, W., Quisumbing, A., Thilsted, S., Hassan Zihad, Z. & Zohir, S. 1998. Commercial vegetable and polyculture fish production in Bangladesh: their impacts on income, household resource allocation, and nutrition. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Bouis, H. & Hunt, J. 1999. Linking food and nutrition security: past lessons and future opportunities. Asian Dev. Rev., 17(1 -2): 168 -213.

von Braun, J. & Puetz, D., eds. 1993. Data needs for food policy in developing countries: new directions for household surveys. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute.

von Braun, J. & Kennedy, E., eds. 1994. Agricultural commercialization, economic development, and nutrition. Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University Press.

Broca, S. & Oram, P. 1991. Study on the location of the poor. Paper prepared for the Technical Advisory Committee to the CGIAR. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Chen, S. & Ravallion, M. 2000. How did the world's poorest fare in the 1900s? Policy Research Working Paper Number 2409. Development Research Group, Poverty and Human Resources. Washington, DC, The World Bank.

Chern, W.S. & Senauer, B. 1993. Pooled time -series and cross -section data from the consumer expenditure survey. In Emerging data issues in applied food demand analysis. Proceedings of a workshop held by the S216, Food Demand and Consumption Behavior Regional Committee, October 1993 (available at http://econpapers.hhs.se/paper/wopfdcbrc/s21693cher01.htm).

Datt, G., Simler, K., Mukherjee, S. & Dava, G. 2000. Determinants of poverty in Mozambique: 1996 -97. Food Consumption and Nutrition Division Discussion Paper No. 78. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Deaton, A. & Irish, M. 1984. Statistical models for zero expenditures in household budgets. J. Public Econ., 23: 59 -80.

Deaton, A. & Grosh, M. 2000. Consumption. In M. Grosh & P. Gleww, eds. Designing household survey questionnaires for developing countries: lessons from 15 years of the Living Standards Measurement Study, Vol. 1. Washington, DC, The World Bank.

Del Ninno, C., Dorosh, P.A., Smith, L.C. and Roy, D.K. 2001. The 1998 floods in Bangladesh: disaster impacts, household coping strategies, and response. IFPRI Research Report 122. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute.

DHS (Demographic & Health Survey). 2001. Demographic and Health Survey Web site: www.measuredhs.com.

DiNardo, J. & Tobias, J.L. 2001. Nonparametric density and regression estimation. J. Econ. Perspect., 15(4): 11 -28.

Dowler, E. & Seo, Y.O. 1985. Assessment of energy intake: estimates of food supply vs measurement of food consumption. Food Policy, 10: 278 -288.

FAO. 1993. Compendium of food consumption statistics from household surveys in developing countries. Volume 1: Asia. FAO Economic and Social Development Paper 116/1. Rome: FAO.

FAO. 1994. Compendium of food consumption statistics from household surveys in developing countries. Volume 2: Africa, Latin America and Oceana. FAO Economic and Social Development Paper 116/2. Rome: FAO.

FAO. 1996. The sixth world food survey. Rome.

Frankenberger, T.R., Frankel, L., Ross, S., Burke, M., Cardenas, C., Clark, D., Goddard, A., Henry K., Middleberg, M., O 'Brien, D., Perez, C., Robinson, R. & Zielinski, J. 1997. Household livelihood security: A unifying conceptual framework for CARE programs. In Proceedings of the USAID workshop on performance measurement for food security, December 11 -12, 1995, Arlington, VA. Washington, DC, United States Agency for International Development.

Garrett, J.L. & Ruel, M.T. 1999. Are determinants of rural and urban food security and nutritional status different? Some insights from Mozambique. World Dev., 27(11): 1955 -1975.

Goodwin, B.K. & Ker, A.P. 1998. Nonparametric estimation of crop yield distributions: implications for rating group -risk crop insurance contracts. Am. J. Agric. Econ., 80(1): 139 -153.

Grootaert, C. & Cheung, K.F. 1985. Household expenditure surveys: some methodological issues. LSMS Working Papers No. 22. Washington, DC, The World Bank.

Grosh, M. & Glewwe, P., eds. 2000. Designing household survey questionnaires for developing countries: lessons from 15 years of the Living Standards Measurement Study, Vol. 1. Washington, DC, The World Bank.

Haddad, L. 2001. DFID -funded technical support facility to FAO's FIVIMS. Technical Paper 1. Deepening the analysis of the factors behind progress towards WFS targets. Report submitted to Overseas Development Institute.

Hentschel, J. & Lanjouw, P. 1996. Constructing an indicator of consumption for the analysis of poverty: principles and illustrations with reference to Ecuador. LSMS Working Paper No. 124. Washington, DC, The World Bank.

Hoddinott, J. 2001. Choosing outcome indicators of household food security. In J. Hoddinott, ed. Food security in practice: methods for rural development projects, pp. 31 -45. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Hoddinot J., Skoufias, E. & Washburn, R. 2000. The impact of PROGRESA on consumption: a final report. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Hoddinott, J. & Yohannes, Y. 2002. Dietary diversity as a food security indicator. Food Consumption and Nutrition Discussion Paper No. 136. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute.

ICN (International Conference on Nutrition). 1992. Caring for the socioeconomically deprived and nutritionally vulnerable. Major Issues for Nutrition Strategies Theme Paper No. 3. ICN/92/INF/7. Rome, FAO/WHO.

Kennedy, E., Ferro-Luzzi, A., Mason, J. & Smith, L. 2002. Response to Professor Svedberg by external experts. Written in response to Svedberg, Peter, "Misleading about hunger in the world. "Svenska Dagbladet, October 13, 2001 (available at www.fao.org/sof/sofi/experts.htm).

Lagiou, P., Trichopoulou, A. & the DAFNE contributors. 2001. The DAFNE initiative: the methodology for assessing dietary patterns across Europe using household budget survey data. Public Health Nutr., 4 (5B): 1135 -1141.

Larson, R.B. 1997. Food consumption and seasonality. J. Food Distrib. Res., 28(2): 36 -44.

Maxwell, D., Levin, C., Armar -Klemesu, M., Tuel, M., Morris, S. & Ahiakeke, C. 2000. Urban livelihoods and food and nutrition security in Greater Accra, Ghana. IFPRI Research Report No. 112. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Maxwell, S. & Frankenberger, T.R. 1992. Household food security: concepts, indicators, measurements. Rome and New York, International Fund for Agricultural Development and United Nations Children's Fund.

Ministry of Planning and Finance, Government of Mozambique/Universidade Eduardo Mondlane/International Food Policy Research Institute. 1998. Understanding poverty and well -being in Mozambique: the first national assessment (1996 -97). Maputo and Washington, DC, Ministry of Planning and Finance and International Food Policy Research Institute.

MPAR. 1998. Understanding poverty and well -being in Mozambique: the first national assessment (1996 -97). Washington, DC, Ministry of Planning and Finance, Eduardo Mondlane University and International Food Policy Research Institute.

Naiken, L. 1998. Statistical problems associated with the estimation of the distribution of household per caput kilocalorie consumption for the purpose of estimating the prevalence of undernutrition. Rome, FAO (ESSA) (mimeo).

Naska, A., Vaskekis, V.G.S. & Trichopoulou, A. 2001. A preliminary assessment of the use of household budget survey data for the prediction of individual food consumption. Public Health Nutr., 4 (5B): 1159 -1165.

Obrien-Place, P. & Frankenberger, T.R. 1988. Food availability and consumption indicators. Nutrition in Agriculture Cooperative Agreement Report No. 3. Washington, DC, US Department of Agriculture, Office of International Cooperation and Development, Nutrition Economics Group in Cooperation with Agency for International Development, Bureau of Science and Technology, Office of Nutrition.

Perali, C.F. & Cox, T.L. 1995. Issues in data management of expenditure surveys: an example from the Colombian 1984 -85 Survey. Agricultural Economics Staff Paper Series No. 389. Madison, WI, University of Wisconsin.

PRC (People's Republic of China). 1992. Food consumption data from the urban and rural household surveys in China, 1985 and 1990. Prepared by the State Statistical Bureau, People's Republic of China in collaboration with the Statistical Analysis Service, Statistics Division, Economic and Social Policy Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Ravallion, M., Datt, G. & van de Walle, D. 1991. Quantifying absolute poverty in the developing world. Rev. Income Wealth Ser., 37(4): 345 -361.

Ravallion, M. & Chen, S. 1996. What can new survey data tell us about recent changes in distribution and poverty? World Bank Econ. Rev., 11(2): 357 -382.

Ruel, M. 2002. Operationalizing dietary diversity: conceptual and measurement issues. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute (mimeo).

Skoufias, E. 2001. Is the calorie income elasticity sensitive to price changes? Evidence from Indonesia. Washington, DC, International Food Policy Research Institute (mimeo).

Smith, L. 1998. Can FAO's measure of chronic undernourishment be strengthened? Food Policy, 23(5): 425 -445.

Stata Statistical Software: Release 7.0. 2000. College Station, TX, Stata Corporation.

Svedberg, P. 2000. Poverty and nutrition: theory, measurement, and policy. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Trichopoulou, A. & Lagiou, P. 1998. The DAFNE food data bank as a tool for monitoring food availability in Europe. DAta Food NEtworking. Public Health Rev., 26(1): 65 -71.

Trochim, W.M.K. 2001. Research methods knowledge base (available at http://trocim.human.cornell.edu).

UN. 1984. Handbook of household surveys. New York, United Nations Department of International Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations.

Vasdekis, B.G.S., Stylianou, S. & Naska, A. 2001. Estimation of age -and gender-specific food availability from household budget survey data. Public Health Nutr., 4(5B): 1149 - 1151.

WHO. 1985. Energy and protein requirements. Technical Report Series 724. Geneva.

World Bank. 1986. Poverty and hunger: issues and options for food security in developing countries. Washington, DC.

|

[6] Note that data from 1970s

and 1980s often did not have this quality (von Braun and Puetz, 1993; Svedberg,

2000). [7] Food quantities are most often reported in local units of measure, such as bags, heaps. tins, and baskets. In this case, collection of data on metric weights must also take place, either at the household level or in local markets. [8] For more information on these tables, see the INFOODS home page at www.fao.org/infoods. Data on aggregated categories of foods (e.g. fruits), for which kilocalorie values are not reported, are often collected in household expenditure surveys. In this case, it is necessary to resort to secondary sources on the nutrient values of single food items consumed within the aggregated group for the average household in the country. This does not pose a major problem of error because in most cases, kilocalorie values for the single food items in a group vary relatively little. Examples of the use of previously collected national surveys of food consumption and food balance sheet data for this purpose can be found in PRC (1992) and Trichopoulou and Lagiou (1999). [9] The percent of total food expenditures on meals away from home is quite small for some countries; for example it is only 4 percent in Nepal but quite large in others (for example, 17 percent in Costa Rica) (FAO, 1993, 1994). [10] Ample allowance must be made for the fact that any household can acquire much more than its members can possibly eat or much less than they need. [11] IFPRI plans on conducting research into the feasibility of such solutions as part of its collaborative project with the FAO and the World Bank "Improving the empirical basis for assessing food insecurity in developing countries". [12] Crude estimates of the percent of individuals who are energy deficient can be computed by assigning the status of a household to each individual in it. Alternatively, both parametric and non-parametric techniques can be employed to attribute food quantity or energy availability to individual age and sex groups (see Naska, Vaskekis and Trichopoulou, 2001; Vasdekis, Stylianou and Naska, 2001. [13] Note that the commonly employed procedure of simply dividing the household kilocalorie availability measure by the number of household members (giving per-capita kilocalorie availability) and comparing it with a national average requirement can lead to erroneous classifications of individual households. Those containing relatively large numbers of small children will tend to incorrectly appear to fall below requirements. Similarly, those containing relatively large numbers of adults, often richer than households with large numbers of small children, will tend to appear to fall above requirements. [14] Care is defined as "the provision in households and communities of time, attention, and support to meet the physical, mental, and social needs of the growing child and other household members (ICN, 1992). [15] Optimally such a measure should be adjusted to account for the prices faced by different population groups, especially geographic and income groups. [16] Given sample size limitations, it is generally only possible to disaggregate estimates to the first-and maybe second -tier administrative levels of a country. Below these levels, problems of precision (high standard errors) begin to arise. For example, in the AFINS project analysis of the Uganda National Household Survey (1999/2000), while precise estimates of energy availability per capita could be obtained at the national level and for the four main regions of the country, they could not be obtained for five of the 41 districts. [17] Note that some of the country-level data used to construct these percentages are based on measures of income rather than total expenditures. [18] FAO uses the term "undernourishment" to describe its measure. |