by

Roland Wiefels

Director, INFOPESCA

Montevideo, Uruguay

1. THE GROWTH OF LATIN AMERICAN FISHERIES DURING THE LAST 40 YEARS

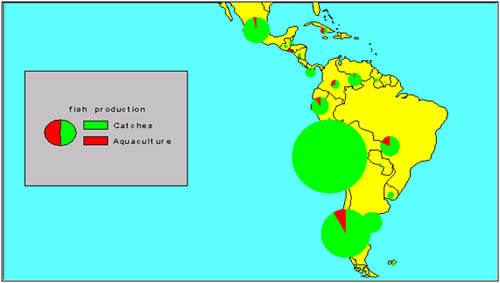

The last 40 years have seen the full development of fisheries in Latin America, even if its participation in the world production has decreased from 16.8 percent in 1961 to 14.1 percent in 1999, which means that the growth rate of Latin American fisheries was less that the global one. Largely based on the production of fishmeal in 1961 (when 82.7 percent of the production was reduced into meal), Latin American fisheries have diversified during these four decades and only 62.8 percent of the production were destined to meal in 1999 (see Table 1). Main fishmeal producers are Peru and Chile, based on their huge resources in small pelagics. In 2000, Peru's fish production was 10.7 million metric tonnes and Chile's 4.7 million metric tonnes, of which 8.3 percent from aquaculture (Figure 1).

The increase in fisheries production was due to the existence of natural resources combined with demanding markets both domestically and worldwide. During this period, Latin American exports of seafood products were multiplied by 12,4 (not considering fishmeal) and the Latin American share in the world export of seafood jumped from 5.4 percent to 11.8 percent during this period (13.6 percent in value in 1999 with nearly US$ 6.4 billion FOB). In the same time, the per capita consumption of seafood in Latin America increased 63 percent even with its fast growing population. 7.2 percent of humankind was Latin Americans in 1961. They were 8.5 percent in 1999.

Despite a recorded absolute growth in the import of seafood during this period, the relative participation of the region in the world imports has declined from 5.6 percent in 1961 to 3.6 percent in 1999.

Table 1: Main Latin American fisheries figures in 1961 and in 1999

|

|

1961 |

1999 |

growth (percent) |

|

Fish production |

6 565 200 MT |

17 214 394 MT |

162.2 |

|

Non food uses |

5 427 710 MT |

10 809 441MT |

99.2 |

|

Imports |

238 970 MT |

942 238 MT |

294.3 |

|

Exports |

242 042 MT |

3 006 786 MT |

1142.3 |

|

Seafood supply |

1 209 407 MT |

4 405 900 MT |

264.3 |

|

Population |

223.1 million |

503.3 million |

125.6 |

|

Yearly per capita fish consumption |

5.4 kg |

8.8 kg |

63 |

Source: FAO Fishery Statistics Yearbooks

For the time being, there is neither record nor estimation of how much investment, public and private, was effectively needed to reach this growth in Latin American fisheries during the period, nor how much was actually paid by international organizations, governments and private enterprises.

The growth of Latin American exports of seafood shows clearly that obtaining hard currencies was the main objective of fisheries development in the region. Meanwhile, it is also clear that, additionally, the supply to the local markets has strongly increased during the same period. If, at this stage, we cannot visualize any evident cause-effect relationship between food security and trade, at least we observe that the simultaneous increase of both is indubitably possible.

Figure 1: Fish production in Latin American countries - year 2000

Source: based on FAO yearbook of fisheries statistics 2000

2. DIFFERENTIATED APPETITE FOR SEAFOOD

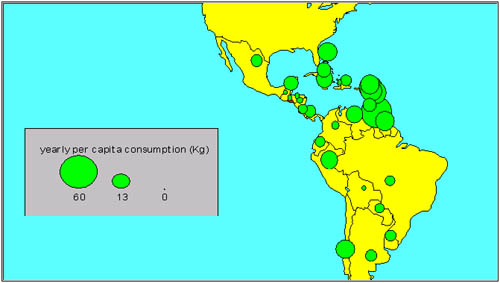

Not all people in the world have the same appetite for seafood, due to cultural reasons or to the more or less availability of the products. It is logical to think that coastal populations as well as those living on islands consume more fish than those living in landlocked countries. This is the general case of Latin America where the populations of the Caribbean islands and on the Caribbean coastline of South America have the highest per capita consumption in the region, up to 57.4 kg in Guyana in 1999, very far from the regional average of 8.8 kg (Figure 2). In the two giant producing countries of the region, the consumption is also much higher than the regional average: 21.1 kg in Chile and 19.2 kg in Peru.

The average consumption is as low as 8.8 kg due to the demographic reality of populated countries like Brazil (168.2 million inhabitants with a per capita consumption of 6.1 kg in 1999) or Colombia (41.4 million inhabitants with a per capita consumption of 3.8 kg in 1999). It is interesting to notice that the four countries of the MERCOSUR (Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina) have similar per capita consumption levels, including landlocked Paraguay.

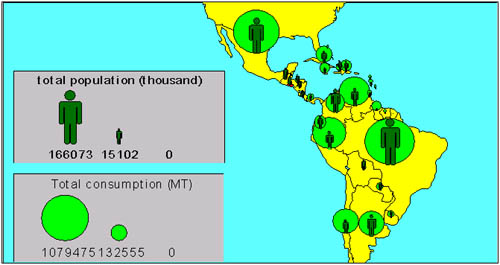

However, total consumption of Latin American countries tends to follow the size of their population. Brazil and Mexico, adding both more than the half of Latin American population are the biggest markets for seafood, despite their relatively low per capita consumption (Figure 3). In Brazil, total consumption of seafood was up to1.03 million metric tonnes in 1999.

Figure 2: Yearly per capita consumption of seafood - 1999

Source: based on FAO fisheries circular n° 821

Figure 3: Total consumption and population in Latin American countries - 1999

Source: based on FAO fisheries circular n° 821

Note: In Figure 3, where the circle of total consumption is bigger than the man representing the total population, it means that the per capita consumption is bigger than the regional average of 8.8 kg. In the opposite case (man bigger than the circle), it means that the per capita consumption in the country is lower than the regional average.

3. LATIN AMERICA: A STILL LARGELY SEAFOOD EXPORTING REGION

Consuming 4.4 million metric tonnes of seafood yearly, Latin America still exports yearly 3 million metric tonnes of seafood and 2.1 million metric tonnes of fishmeal, for a total value of US $ 6.1 billion (yearly average 1998-2000).

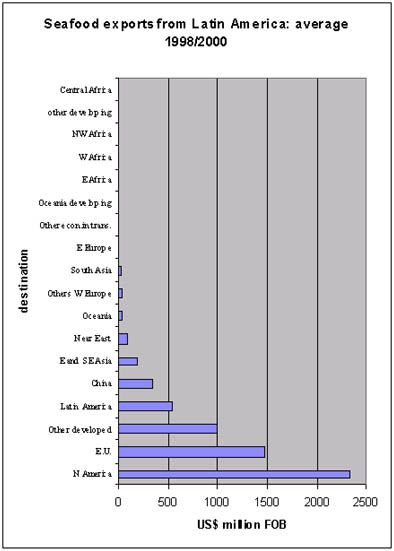

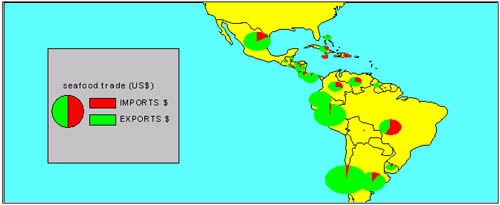

Figure 4: Current destination of Latin American seafood exports

As for the current destinations of Latin American seafood exports, the "three big markets" (USA, EU and Japan - this last country being identified in Figure 4 under the name of "other developed") continue to represent 75 percent of the market share.

There is no historical series available in order to allow comments on the evolution of the market shares, but it seems clear that new markets are arising, mainly inside Latin America itself, as well as in China, in East and South East Asia and in the Near East.

These regions do not only represent markets for seafood, but also for many other Latin American food products, particularly meat and poultry. The big fish producing countries in Latin America are also the big fish exporters (Figure 5). Chile's foreign trade in fisheries products was up to US$ 1.8 billion in 2000, of which 2.6 percent were imports and 97.4 percent exports. In Peru, the amount was US$ 1.1 billion.

It is interesting to see that, despite being producers and exporters, many countries also have imports as an important share of their foreign trade in fisheries products. The most visible example on Figure 5 is Brazil, with US$ 324.2 million imports, compared with only US$ 239.1 million exports in 2000.

Figure 5: foreign trade (value) in fisheries products - year 2000

Source: based on FAO yearbook of fisheries statistics 2000

4. SEAFOOD TRADE AND FOOD SECURITY ON A LATIN AMERICAN REGIONAL BASE

It is difficult to find any obvious relationship between trade in fisheries products and food security on a regional or even on a national scale: there are too few available data and information about the fishery sector (number of fishermen, fish farmers, workers, marketers, etc) and too many factors affecting food security (national economics policies and their results, labour realities, official policies, weather...), besides the fisheries sector.

Further to observing that both, seafood trade and increased local consumption of seafood coexist on a regional basis, it is possible to imagine that seafood trade encourages consumption by increasing not only the volume but also, and mainly, the variety of seafood offer. For the time being, having in mind the availability of data regarding food security on a regional basis, it is difficult to conclude much more.

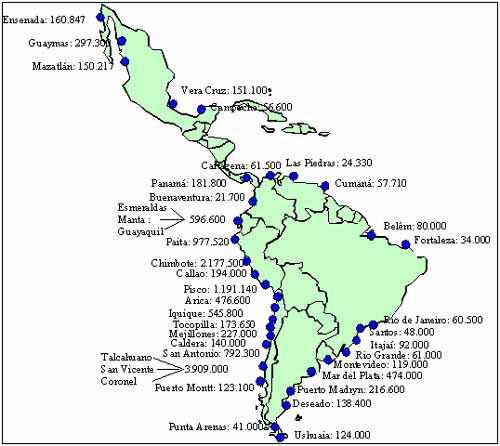

5. CONCENTRATION OF ACTIVITIES IN FISHERIES POLES/CLUSTERS

An important aspect of Latin American fisheries is that the activity is somewhat concentrated in big fishing poles. For instance, we observe that only 35 fishing harbours concentrate 60 percent of the regional production (Figure 6). In these harbours are also located most of the seafood processing industry and many related activities and services (shipyards, traders, transport services, etc.), some of them having all the characteristics of fishery clusters. Aquaculture is concerned the same way than fishing: Guayaquil in Ecuador and Puerto Montt in Chile are both aquaculture clusters.

Being geographically concentrated in towns where the fishery activity is at least an important economic sector, if not the most important one, it is easier to identify possible relationships between trade and food security. Normally, if the fishery business is working well in a fishing town, the rate of employment will be high, with good consequences on families’ incomes, and food security will be possibly assured for most of the population. Of course, this is also valid for any economic activity and not only for fisheries.

Figure 6: the 35 main fishery poles in Latin America - 60 percent of the production

Source: Wiefels, 1999; landings of 1994

6. CONCLUSIONS

It seems to be very difficult to establish a well defined relationship between fish trade and food security on a regional base. It seems that the difficulty would be the same on a national base, at least in the big countries of Latin America (i.e. Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, Peru...) due to the complexity of their economy. For instance it is difficult to clearly establish what the role is of the lower exports of Argentinean hake (which was due to overfishing and lower catches) on food security in Argentina, without considering all the macro economical parameters of the country. On a national base, in this Argentinean example, it is obvious that the role of lower exports of hake is insignificant in the growth of national food insecurity.

It is however clear that in most Latin American countries; the development of fisheries activities was motivated by the existence of foreign markets. In this case, all the incomes of the fisheries sector and stakeholders can be linked to trade. The problem which might appear in these cases is how to evaluate the actual rate of return of the investments in the fisheries sector and who are the actual beneficiaries of the benefits. In some cases, national subsidies to fisheries development (which was usual in many Latin American countries during the decades of 1970 and 1980) have benefited dubious entrepreneurs and had no real influence on national food security. In other cases, investments were done by multinationals having in mind the quick repatriation of their capitals and benefits.

The problem therefore seems to be the scale of the region under study. If we consider very specific and small communities, it might be possible to identify an eventual link between fish trade and local food security, as it is the case of the exports of Nile Perch on local people in the Lake Victoria fisheries. But the small or even very small scale of such communities turns any link between trade and food security anecdotal. Any conclusion on one specific case would be difficult to generalize.

It could be possible in Latin America to identify some situations, which might be similar to the Lake Victoria's one, but it seems difficult to provide sound conclusions regarding the world fisheries and international trade of seafood as a whole and its relationship with food security.