E.J. Wailes[9], Professor of Agricultural Economics, University of Arkansas

ABSTRACT

The Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture represented a turning point in the history of the multilateral trading system by subjecting agricultural trade to essentially the same rules that discipline trade in industrial goods. However, since the signing of the Doha Ministerial Declaration in November 2001, objectives and deadlines for the current round of multilateral negotiations have not been met. Little compromise has been reached on core issues regarding commitments to further expand market access, reduce or eliminate export subsidies, and lower trade-distorting domestic supports.

Through the 1990s trade liberalization has had a positive impact on the international rice market because rice trade has been highly protected in both industrialized and developing nations. The relatively modest terms of agreement in the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture along with regional trade agreements and national policy reforms have contributed to a doubling in global rice trade in the latter half of the 1990s. Nevertheless, rice remains with sugar and dairy products, as one of the most protected food commodities in world trade.

The major types of distortion in world rice markets are import tariffs and tariff rate quotas in key importing countries and price supports in key exporting countries. In 2000, the global trade weighted average tariff on all rice was 43 percent. Medium grain rice markets however are far more distorted than long grain rice markets due to the TRQs and quotas in the major medium grain rice importing countries of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Global trade weighted average rice tariffs in 2000 for medium and short grain rice markets were 217 percent compared to 21 percent for the long grain market. In addition to trade protection by rice type, an important dimension of world rice trade is protection for the domestic rice milling industry. This form of protection is expressed in tariff escalation and is especially prevalent in Central and South American nations and the European Union. Price supports for rice producers have been important in the major industrialized countries or regions including the European Union, Japan, and the United States.

The Doha Round of trade negotiations has moved slowly as countries have been unwilling to compromise on market access, export subsidy, and domestic support proposals. This paper attempts to measure the potential gains from the removal of policy distortions in the global rice economy along the lines being negotiated in the Doha Round. Two different types of modeling frameworks are used to estimate trade, price and economic welfare effects of policy reform in the global rice economy.

Using a static spatial equilibrium trade model (RICEFLOW), complete rice trade liberalization in 2000 would have resulted in an expansion in global rice trade of nearly 3.5 mt, a 15 percent increase in trade compared to actual 2000 rice trade. Trade weighted average export prices would be 32.8 percent higher and trade weighted import prices would be 13.5 percent lower. Because of differences in protection by rice type and degree of milling, the results presented reflect that the greatest gains in trade volume and elimination of price distortions are for the medium grain markets. Trade in medium/short grain with trade liberalization would increase by 73 percent. Producer export medium grain prices would rise by 91 percent and import prices would decline by 27 percent, improving consumer welfare in rice importing nations. Long grain rice trade liberalization results in a 7 percent increase in volume traded. Long grain export prices increase by only 2 percent but import prices fall by 18 percent. Most of the expansion in long grain trade occurs in the low quality markets such as Indonesia, Bangladesh and Philippines. Global rice trade liberalization results in a total economic surplus gain of US$7.4 billion annually. Importing countries, as a group, have a net gain of US$5.4 billion and exporting nations gain US$2 billion. The magnitudes of the net gains vary considerably by country and by rice type and degree of milling.

Using a dynamic non-spatial global rice trade model (Arkansas Global Rice Model), the removal of import tariffs, export subsidies, and domestic support are measured in scenario analyses separately and combined. The impact on global rice trade from the removal of tariffs dominates all policy reform scenarios. The combined effect of the removal of tariff barriers, export subsidies, and domestic supports increases trade by 2.4 mt in 2005 and increases to 4.9 mt by 2012. Long grain export prices are higher by 18 to 22 percent, slightly higher than the estimated impact using the RICEFLOW model. Medium grain prices are higher than baseline projections by 70 to 80 percent, a result similar to the findings reported using the RICEFLOW model.

Multilateral and regional trade policy reforms achieved over the past decade have contributed to an expansion in rice trade and more stable prices. The achievements of the Uruguay Round Agriculture Agreement include the opening of the previously closed Japanese and Republic of Korean markets. Limits placed on domestic supports in the EU and the US have not had a significant impact on rice trade as these countries have shifted their producer support out of the trade-distorting "amber box" into decoupled payments which are not disciplined under current WTO rules. Regional agreements such as NAFTA and MERCOSUR have increased western hemisphere rice trade. The prospects for the Doha Round of the WTO hinge to a great extent upon continuing the expansion of market access, reduction of tariffs, and limits on producer supports and export subsidies that will be effective. Continued trade policy reforms are important for the global rice economy and will have positive impacts on producers in exporting nations and consumers in importing countries. But reforms will result in losses to other market participants. The exercise of political power by specialized interests in protecting their existing benefits from a policy-distorted global rice sector cannot be underestimated. Therefore it is important to continue efforts to clearly measure and understand the consequences of protection and the benefits of moving forward towards successful negotiations in the Doha Round.

E.J. Wailes[10], Professeur d’économie agricole, Université de l’Arkansas (États Unies)

RÉSUMÉ

En soumettant le commerce des produits agricoles à des règles pratiquement identiques à celles du commerce des biens industriels, l’accord du Cycle de l’Uruguay sur l’agriculture représente un tournant historique pour le commerce multilatéral. Depuis la signature de la Déclaration ministérielle de Doha en novembre 2001, les objectifs et les délais fixés pour le cycle des négociations multilatérales en cours n’ont pas été atteints. Peu d’accords se sont dégagés sur les questions de base qui concernent l’amélioration de l’accès aux marchés, la réduction ou la suppression des subventions à l’exportation, et la diminution des soutiens nationaux qui ont des effets de distorsion des échanges.

Le marché mondial du riz a été stimulé par la libéralisation des échanges dans les années 90. Jusque là, le commerce du riz était en effet fortement protégé dans les nations tant industrialisées qu’en développement. Dans la seconde moitié des années 90, les termes relativement modérés de l’accord du Cycle de l’Uruguay sur l’agriculture ainsi que les accords de commerce régional et les réformes nationales de politiques générales ont contribué à faire doubler les échanges mondiaux de riz. Il n’en demeure pas moins que le riz, à l’instar du sucre et des produits laitiers, est l’un des produits alimentaires les plus protégés du commerce international.

Les taxes à l’importation et les contingents tarifaires dans les principaux pays importateurs ainsi que le soutien des prix dans les gros pays exportateurs représentent les principaux types de distorsion des marchés internationaux du riz. En 2000, la taxe moyenne pondérée sur les marchés mondiaux, pour l’ensemble du riz, était de 43 pour cent. Les distorsions sont beaucoup plus importantes sur les marchés du riz mi-long que sur ceux du riz long, du fait des contingents tarifaires et des quotas appliqués dans les pays importateurs de riz mi-long (Japon, République de Corée et Taiwan). Les taxes moyennes pondérées sur les marchés internationaux de riz mi-long et de riz rond s’élevaient à 217 pour cent, contre 21 pour cent pour le marché du riz long. En sus de la protection commerciale par type de riz, l’une des caractéristiques importantes du marché international du riz tient à la protection des rizeries nationales. Cette forme de protection s’exprime par une progressivité tarifaire et se rencontre souvent dans les pays d’Amérique centrale et d’Amérique du Sud ainsi que dans l’Union européenne. Le soutien des prix en faveur des producteurs rizicoles est une mesure fréquemment appliquée par les principaux pays ou régions industrialisés au nombre desquels figurent l’Union européenne, le Japon et les États-Unis.

Les pays hésitent à changer de position au sujet des propositions relatives à l’accès aux marchés, aux subventions à l’exportation et aux soutiens internes, ce qui freine les progrès du Cycle des négociations commerciales de Doha. Le présent document cherche à mesurer les avantages potentiels que pourrait générer l’élimination des distorsions politiques sur l’économie rizicole mondiale conformément aux négociations du Cycle de Doha. Deux types de cadres de modélisation différents ont été utilisés pour évaluer les conséquences des réformes politiques de l’économie rizicole mondiale sur le commerce, les prix et le bien-être économique.

Si l’on utilise un modèle statique de commerce en équilibre spatial (RICEFLOW), la libéralisation totale des échanges de riz en 2000 se traduit par une augmentation du commerce rizicole international de près de 3,5 millions de tonnes, soit une hausse de 15 pour cent par rapport au volume réel de 2000. Les prix commerciaux moyens pondérés à l’exportation progressent de 32,8 pour cent et les prix commerciaux d’importation pondérés diminuent de 13,5 pour cent. Compte tenu des différences de protection par type de riz et degré d’usinage, les résultats présentés montrent que les plus grands avantages en terme de volume de commerce et de suppression de distorsions de prix reviennent aux marchés du riz mi-long. Dans le cadre d’une libéralisation des échanges, le commerce du riz mi-long/rond augmente de 73 pour cent. Les prix à l’exportation pour les producteurs de riz mi-long enregistrent une hausse de 91 pour cent et les prix d’importation chutent de 27 pour cent, ce qui est bénéfique aux consommateurs dans les pays importateurs de riz. La libéralisation du commerce du riz long se traduit par une croissance de 7 pour cent du volume échangé. Les prix à l’exportation du riz long n’augmentent que de 2 pour cent mais les prix d’importation fléchissent de 18 pour cent. La majeure partie de l’expansion du commerce du riz long concerne les marchés de qualité inférieure, comme l’Indonésie, le Bangladesh et les Philippines. La libéralisation du commerce international du riz se solde par un excédent économique total de 7,4 milliards de dollars E.U. par an. Les pays importateurs, en tant que groupe, obtiennent un gain net de 5,4 milliards de dollars E.U. et les pays exportateurs, de 2 milliards de dollars E.U. L’ampleur des gains nets varient considérablement d’un pays à l’autre, et selon le type de riz et le degré d’usinage.

Si l’on utilise un modèle dynamique, non spatial (Arkansas Global Rice Model), les conséquences de l’élimination des taxes à l’importation, des subventions à l’exportation et des soutiens internes sont mesurées à l’aide d’une analyse de scénarios, séparée ou cumulative. L’incidence de la suppression des tarifs sur le commerce mondial du riz domine tous les scénarios de réformes politiques. L’effet conjugué de l’élimination des obstacles tarifaires, des subventions à l’exportation et des soutiens internes entraîne une croissance des échanges de 2,4 millions de tonnes en 2005 avant de s’établir à 4,9 millions de tonnes d’ici 2012. Les prix d’exportation du riz long augmentent de 18 à 22 pour cent, soit une légère augmentation par rapport à l’estimation du modèle RICEFLOW. Les prix du riz mi-long dépassent les projections de base de 70 à 80 pour cent, ce qui donne un résultat identique aux conclusions du modèle RICEFLOW.

Les réformes politiques du commerce multilatéral et régional adoptées depuis les dix dernières années se sont traduites par un accroissement des échanges de riz et une plus grande stabilité des prix. L’un des résultats positifs de l’accord du Cycle de l’Uruguay sur l’agriculture a été l’ouverture des marchés jusqu’alors fermés du Japon et de la République de Corée. Les limites imposées aux soutiens internes dans l’Union européenne et aux États-Unis n’ont pas eu de conséquence significative sur le commerce du riz. Ces pays ne font plus en effet figurer le soutien qu’ils apportent à leurs producteurs dans la catégorie des effets de distorsion ‘à surveiller’ mais leur fait bénéficier de paiements découplés qui ne sont pas actuellement régis par les règles de l’OMC. Les accords régionaux tels que l’ALÉNA et MERCOSUR ont permis de stimuler les échanges de riz dans l’hémisphère occidental. L’avenir du Cycle de Doha de l’OMC dépend dans une large mesure des efforts qui seront déployés pour continuer à améliorer l’accès aux marchés, réduire les tarifs et diminuer les soutiens internes et les subventions à l’exportation. La poursuite des réformes des politiques commerciales sera favorable à l’économie rizicole mondiale et bénéficiera aux producteurs des pays exportateurs et aux consommateurs des pays importateurs. Ces réformes entraîneront toutefois des pertes pour d’autres participants au marché et il ne faut pas sous-estimer le pouvoir politique exercé par des intérêts particuliers en vue de protéger les avantages que leur procurent les distorsions politiques actuelles du secteur mondial du riz. Il est donc important de continuer à s’efforcer de mesurer et de comprendre clairement les incidences des mesures de protection et les bénéfices qui peuvent découler de la réussite des négociations du Cycle de Doha.

E.J. Wailes[11], Profesor de economía agrícola, Universidad de Arkansas, Estados Unidos

RESUMEN

El Acuerdo de la Ronda Uruguay sobre Agricultura marcó un punto crítico en la historia del sistema multilateral de comercio, al someter el comercio agrícola básicamente a las mismas reglas que rigen el comercio de los productos industriales. Sin embargo, desde la firma de la Declaración de la reunión ministerial de Doha, en noviembre de 2001, no se han cumplido los objetivos ni los plazos de la ronda actual de negociaciones multilaterales. Se han hecho pocas concesiones en las cuestiones centrales relacionadas con los compromisos de ampliar más el acceso al mercado, reducir o eliminar los subsisdios a las exportaciones y reducir las medidas de apoyo interno que distorsionan el comercio.

En el decenio de 1990 la liberalización del comercio produjo repercusiones positivas en el mercado internacional del arroz, ya que el comercio de este cereal había estado muy protegido tanto en los países industrializados como en los países en desarrollo. Las condiciones relativamente moderadas que se aprobaron en el ámbito del Acuerdo sobre la agricultura de la Ronda Uruguay, así como los acuerdos comerciales regionales y las reformas de los países a sus políticas, han contribuido a duplicar el comercio mundial de arroz en la segunda mitad de los años noventa. Sin embargo, el arroz, junto con el azúcar y los lácteos, sigue siendo uno de los productos alimentarios más protegidos en el comercio mundial.

Los principales tipos de distorsiones que hay en el mercado mundial de arroz son los aranceles a las importaciones y los contingentes arancelarios de los principales países importadores, así como los apoyos a los precios en los principales países exportadores. En 2000, el arancel medio ponderado en el comercio mundial del arroz fue de 43 por ciento. Sin embargo, los mercados de arroz de grano medio están mucho más distorsionados que los de arroz de grano largo, debido a los contingentes arancelarios y a los contingentes de los países importadores de arroz de grano medio del Japón, Corea del Sur y Taiwán. Los aranceles medios ponderados mundiales del arroz en 2000 para los mercados de arroz de grano medio y corto fueron del 217 por ciento, en comparación con el 21 por ciento del mercado de arroz de grano largo. Además de la protección comercial por tipo de arroz, otra dimensión importante del comercio mundial del arroz es la protección de la industria interna del arroz. Este tipo de protección consiste en progresividad arancelaria y predomina sobre todo en los países de América Central y América del Sur, así como en la Unión Europea. Los apoyos al productor de arroz a través de los precios han sido importantes casi en todos los principales países o regiones industrializados, comprendidos la Unión Europea, el Japón y los Estados Unidos.

La Ronda de Doha de negociaciones comerciales ha avanzado lentamente porque los países no han estdo dispuestos a hacer concesiones en materia de acceso al mercado, subvenciones a las exportaciones y apoyo interno. Este trabajo se propone medir los posibles resultados de la eliminación de las distorsiones de las políticas en la economía mundial del arroz, de acuerdo a las negociaciones de la Ronda de Doha. Se utilizan dos tipos de modelos para estimar los efectos de las reformas noramativas en el comercio, los precios y el bienestar económico en la economía mundial del arroz.

Mediante un modelo de equilibrio espacial estático del comercio (RICEFLOW), la liberalización completa del comercio del arroz en 2000 hubiera producido un incremento del comercio mundial de este cereal equivalente a casi 3,5 millones de toneladas, lo que representa un aumento del comercio del 15 por ciento en comparación con el comercio efectivo de arroz en 2000. Los precios medios ponderados de las exportaciones serían 32,8 por ciento más elevados y los precios medios ponderados de las importaciones serían 13,5 por ciento más bajos. Debido a las diferencias de protección por tipo de arroz y grado de elaboración, los datos obtenidos señalan que la mayor ganancia en volumen del comercio y eliminación de las distorsiones de los precios correspondería a los mercados de grano medio. El comercio de grano medio y corto en condiciones de liberalización del mercado aumentaría un 73 por ciento. Los precios de exportación del productor de arroz de grano medio aumentarían 91 por ciento y los precios de las importaciones disminuirían un 27 por ciento, lo que incrementaría el bienestar de los consumidores en los países importadores de este cereal. La liberalización del comercio de arroz de grano largo produce un incremento del 7 por ciento del volumen del comercio. Los precios de las exportaciones de arroz de grano largo aumentan sólo un 2 por ciento, pero los precios de las importaciones bajan un 18 por ciento. La mayor parte de la expansión del comercio de grano largo se da en los mercados de baja calidad, como Indonesia, Bangladesh y las Filipinas. La liberalización mundial del comercio del arroz produce un excedente económico total de 7 400 millones de dólares EE.UU. al año. Los países importadores, como grupo, obtienen una ganancia neta de 5 400 millones de dólares y los países exportadores ganan 2 000 millones de dólares. La magnitud de las ganancias netas varía considerablemente de país a país y según el tipo de grano y el grado de elaboración.

Utilizando un modelo no espacial dinámico del comercio mundial de arroz (Arkansas Global Rice Model), la eliminación de los aranceles a las importaciones, los subsidios a las exportaciones y el apoyo interno se miden en análisis separados y combinados. Las repercusiones en el comercio mundial del arroz de la eliminación de los aranceles predominan en todas las hipótesis de reformas de las políticas. El efecto conjunto de la eliminación de obstáculos arancelarios, subsidios a las exportaciones y apoyo interno se traduce en un aumento del comercio de 2,4 millones de toneladas en 2005 y de 4,9 millones de toneladas para 2012. Los precios de las exportaciones de arroz de grano largo son más altos de 18 por ciento a 22 por ciento, ligeramente más elevados que las repercusiones estimadas con el modelo RICELFOW. Los precios del grano medio son más elevados que las proyecciones básicas por entre 70 por ciento y 80 por ciento, resultado parecido al obtenido con el modelo RICEFLOW.

Las reformas a las políticas multilaterales y regionales del comercio realizadas en el último decenio han contribuido a la expansión del comercio del arroz y a la estabilidad de los precios. Los resultados del Acuerdo sobre la agricultura de la Ronda Uruguay incluyen la apertura de los mercados antes cerrados del Japón y Corea del Sur. Las limitaciones impuestas a los apoyos internos en la UE y los Estados Unidos no han producido repercusiones importantes en el comercio del arroz, ya que estos países han sacado del "compartimento ámbar" de distorsiones al comercio su apoyo a los productores para pasar a la realización de pagos desacoplados que no están sujetos a las reglas vigentes de la OMC. Acuerdos regionales como el TLC y MERCOSUR han incrementado el comercio de arroz en el hemisferio occidental. Las perspectivas de la Ronda de Doha de la OMC dependen en gran medida de que siga abriéndose el acceso al mercado, de la reducción de los aranceles y de poner límites eficaces a los apoyos a los productores y a las subvenciones a las exportaciones. Para el comercio mundial del arroz es importante que se sigan introduciendo reformas comerciales, que producirán repercusiones positivas en los productores de los países exportadores y en los consumidores de los países importadores. Pero otros participantes en el mercado sufrirán pérdidas a causa de las reformas. No se puede subestimar el poder político que ejercen los intereses especializadas para proteger los beneficios de que gozan actualmente en un sector mundial del arroz con políticas distorsionadas. Por lo tanto, es importante seguir tratando de medir y entender con claridad las consecuencias de la protección y los beneficios de avanzar hacia el éxito de las negociaciones de la ronda de Doha.

E.J. Wailes[12], Professor of Agricultural Economics, University of Arkansas

Introduction

The Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture represented a turning point in the history of the multilateral trading system by subjecting agricultural trade to essentially the same rules that discipline trade in industrial goods. For the first time, WTO members committed to reducing agricultural tariffs, export subsidies, and domestic support. The agreement also committed members to start negotiations on continuing these reforms beginning in 2000. With the signing of the Doha Ministerial Declaration in November 2001, objectives and deadlines for the current round of multilateral negotiations were set. While some progress has been made, little compromise has been reached on core issues regarding commitments to further expand market access, reduce or eliminate export subsidies, and lower trade-distorting domestic supports.

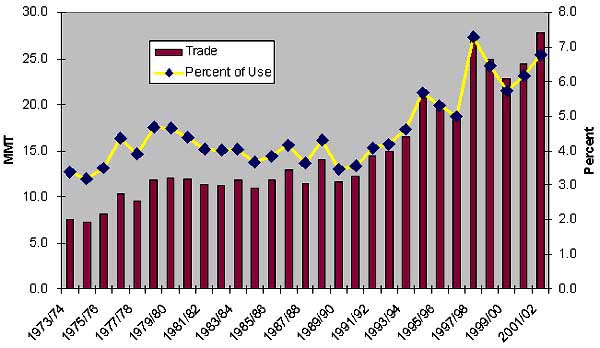

Trade liberalization is having a profound impact on the international rice market because rice trade has been highly protected in both industrialized and developing nations (Wailes, 2002). The relatively modest terms of agreement in the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture along with regional trade agreements and national policy reforms have contributed to the sharp increase in global rice trade growth experienced in the latter half of the 1990s (Figure 1). Compared to the 1970s and 1980s, post-Uruguay Round rice trade has essentially doubled in both volume and as a share of consumption. Nevertheless, rice remains with sugar and dairy products, as one of the most protected food commodities in world trade.

Policy distortions in global rice trade

The major types of distortion in world rice markets are import tariffs and tariff rate quotas in key importing countries and price supports in key exporting countries. In 2000, the global trade weighted average tariff on all rice was 43.3 percent. Medium grain rice markets are far more distorted than long grain rice markets due to the TRQs and quotas in the major medium grain rice importing countries of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Global trade weighted average rice tariffs in 2000 for medium and short grain rice markets were 217 percent compared to 21 percent for long grain markets.

Price supports for rice producers have been important in the major industrialized countries or regions including the European Union, Japan, and the United States. Both the EU and the US have shifted much their support mechanisms to decoupled payments and therefore out of WTO amber box discipline. Yet it is clear that without such payments, producers in these regions would be challenged to maintain current production levels. Much of the price support in Japan extends from the tariffs and TRQ levels. Since 1998, Japan’s internal market intervention applies only to maintaining rice stocks for food security. Therefore, Japan’s notification of domestic support as an aggregate measure of support (AMS) is remarkably low, while at the same time the producer subsidy equivalent measure (PSE), which reflects both domestic and border support, remains extremely high.

In addition to trade protection by rice type, an important dimension of world rice trade is protection for the domestic rice milling industry. This form of protection is expressed in tariff escalation and is especially prevalent in Central and South American nations and the European Union. Tariffs on milled rice are higher than for brown or paddy rice. Tariffs on milled rice imports into the EU are more than twice the tariff level for brown rice. In Mexico, paddy rice imports pay a 10 percent tariff while brown and milled pay a 20 percent tariff. The effect of tariff escalation is seen in the reduced trade flows of milled high quality long grain. Most of this trade goes to nations with low tariffs. Most of the trade in brown and paddy rice however goes to nations that have high tariffs on brown and paddy, but even higher tariffs on milled rice. The trade weighted average tariffs by degree of milling for high quality, long grain rice is estimated to be 4.3 percent for milled, 31.4 percent for brown and 16.9 percent for paddy rice. This compares to simple non-trade weighted averages for milled of 13.7 percent, brown 18.7 percent and paddy 25.4 percent.

The greatest degree of protection in world rice trade is for medium/short grain. World export prices of medium/short grain rice are lower by approximately 100 percent as a result of protection by Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. Currently very few rice exporting countries produce medium/short grain rice. While potential to expand production of medium grain rice in non-traditional areas exists, there has not been an adequate price incentive to induce the research and development of production systems necessary to compete for these markets. The clear beneficiaries of trade liberalization in medium/short grain rice in the longer term, with expanded market access, will be those countries and especially China, which have a competitive advantage in production costs and logistics relative to other traditional medium grain export competitors, the United States, Australia, and Egypt.

Trade liberalization may stimulate production of medium/short grain in other countries but currently traded varieties are mainly suitable for temperate climates. Thus South American production, particularly Argentina and Uruguay, could develop adapted varieties more quickly. Many other developing countries have tropical or sub-tropical climates, thus these countries likely would require a decade or more to develop varieties that would be competitive into a liberalized medium/short grain global market. Production capacity for medium grain rice in Australia and the United States and to some degree China is increasingly constrained by lack of irrigation water.

Long grain rice markets are far less protected than medium grain. Tariffs in major low quality rice importing nations such as Indonesia and Bangladesh are estimated to reduce world export prices by as much as 30 percent compared to prices under full liberalization. The major impact of protection in low quality rice markets falls on consumers in these low-income importing developing nations and producers in low quality rice exporting nations such as Vietnam, India, Pakistan, and Thailand. Tariffs in high quality long grain markets are low by comparison with medium/short grain markets and low quality long grain markets. The most significant aspect of tariffs in high quality long grain rice trade is tariff escalation, where countries, particularly the European Union and several Central and South American nations have particularly high tariffs on milled rice relative to brown or paddy rice. This pattern of protection depresses world prices for milled high quality long grain relative to brown and paddy rice prices and places economic hardships on the milling sectors of high quality, long grain exporting nations such as Thailand, Vietnam, and the United States. Protection in high quality long grain milled rice markets is estimated to reduce world export prices by 10 to 20 percent.

As a result of slower and longer-term market access reforms allowed for developing countries in the WTO, rice policies in developing countries have not changed significantly over the past decade. The lack of rice policy reforms in developing countries has resulted in greater price volatility, which has placed a heavy burden directly on poor consumers or on the government to provide food distribution Programmes for those in poverty. The coefficient of variation of domestic prices in real terms over the past 20 years was 0.43 in India, 0.26 in Indonesia, and 0.37 in China over the past 16 years. These measures of price volatility compare with the coefficient of variation of only 0.24 of the Thai export price in real terms.

Estimates of policy reforms in the global rice sector

Recent official and unofficial meetings on agricultural negotiations of the Doha round have created a sense of frustration of not being able to move forward. The costs of negotiation, to find agreement to achieve further reform within the WTO framework, appear to be high. Are then the potential benefits of pursuing further reforms worth the effort? In recently completed research we have explored the question of what are the potential gains from near complete policy reform in the global rice markets (Wailes, 2004). Global rice trade liberalization is found to result in significant expansion of rice trade and price adjustments. Estimates of the impact of the elimination of import tariffs, export subsidies, and domestic supports were generated through the use of two modeling frameworks, a spatial equilibrium model, RICEFLOW (Durand-Morat and Wailes, 2003) and the Arkansas Global Rice model, a dynamic econometric framework (Fuller, Wailes, and Djunaidi, 2003). An earlier version RICEFLOW was used to assess trade liberalization prior to the Uruguay Round. For this study, RICEFLOW was more completely disaggregated by rice type and degree of milling and the baseline trade flows and elasticity estimates were updated through the year 2000. The results reflect the effects of trade liberalization applied to year 2000 trade flows and prices. A summary of the analysis by quantities traded and prices are presented in Table 1.

Complete rice trade liberalization in 2000 would have resulted in an expansion in global rice trade of nearly 3.5 mt, a 15 percent increase in trade compared to actual 2000 rice trade. Trade weighted average export prices would be 32.8 percent higher and trade weighted import prices would be 13.5 percent lower.

Results by rice type and degree of milling also provide interesting estimates. As noted above, protection in medium/short grain rice markets is substantially greater than in long grain rice markets. Trade in medium/short grain with trade liberalization would increase by 73 percent. Producer export prices would rise by 91 percent and import prices would decline by 27 percent. In the most protected brown medium/short grain rice markets, trade increases by 141 percent, export prices increase by 200 percent and import prices decrease by 41 percent. Milled medium/short grain rice markets would expand by 59 percent, with export prices higher by 71 percent and import prices lower by 25 percent.

Long grain rice trade liberalization results in a 7 percent increase in volume traded. Export prices increase by only 2 percent but import prices fall by 18 percent, improving consumer welfare in rice importing nations. Most of the expansion in long grain trade occurs in the low quality markets such as Indonesia, Bangladesh and Philippines. Traded low quality long grain volumes increase by 13 percent and import prices fall by 14 percent, improving consumer welfare in many low-income developing countries. Removal of protection in these markets also improves producer welfare in developing countries as export prices increase by 7 percent. In the fragrant rice market of basmati and jasmine rice, free trade results in a 41.5 percent lower import price but only slight increases in the volume traded and the export price.

Trade in the high quality long grain markets is subject to much less protection and as a result, trade liberalization results in only slight increases in volume traded-4 percent more paddy rice, 7 percent more brown rice and 3 percent more milled rice. Price effects are primarily seen in lower import prices-10 percent less for paddy, 31 percent lower for brown and 4 percent lower for milled rice.

Consumer and producer surplus gains and losses are estimated using the results of the baseline and free trade results of the RICEFLOW model. The detailed welfare estimates for producers and consumers and impact on government revenues from tariff elimination and government expenditures from the termination of domestic support Programmes are found in Wailes, 2004.

Global rice trade liberalization results in a total economic surplus gain of US$7.4 billion annually. Importing countries, as a group, have a net gain of US$5.4 billion and exporting nations gain US$2 billion. The magnitudes of the net gains vary considerably by country and by rice type and degree of milling. The estimates are based on the impact of full trade liberalization in year 2000.

Reform of trade in medium grain milled rice accounts for more than 60 percent of the total global welfare improvement at US$4.3 billion, of which importers benefit by US$3.4 billion and exporters by US$905 million. Brown medium grain rice importers benefit by US$1 billion and exporters gain US$449 million. Long grain trade liberalization generates total improvements of US$1.14 billion. Importers gain US$1.06 billion and exporters gain US$80 million. High quality rice trade has welfare improvements of US$218 million, with importers gaining US$195 million and exporters gaining US$23 million. Most of these gains occur for high quality milled, US$69 million and brown rice, US$124 million. Paddy rice trade liberalization improves the welfare of exporters by US$2.4 million and importers by US$22.4 million. Low quality rice trade liberalization improves the welfare of importing nations by US$315 million and exporters by US$52 million. Nearly all of these gains are captured by developing countries. Fragrant rice trade reform is estimated to improve importers welfare by US$547 million, a result due primarily to Japan. Exporting nations of fragrant rice, India, Pakistan and Thailand gain only US$6 million annually.

The trade and welfare analysis presented above assessed trade reform based on elimination of trade and domestic policies using the RICEFLOW model, a static spatial equilibrium framework of excess supply and demand equations. This framework is limited to estimation of the effects of policy reform pertaining to border protection. Domestic policy reforms were implicit in the policy results. It is not possible to use RICEFLOW to assess directly the effects of domestic price support policies on world rice trade and prices. To examine this additional effect, the Arkansas Global Rice Model (AGRM) was used. The AGRM is a non-spatial dynamic econometric model of the global rice economy (Fuller, Wailes, and Djunaidi, 2003). The AGRM structure is based on equations for supply-expressed in terms of equations that estimate area harvested and yields; and for demand-expressed in equations for domestic consumption, exports, imports, and ending stocks. Rice prices are endogenized, with world reference equilibrium prices for long grain and medium grain rice.

The effects of domestic price supports and trade policy are captured in the supply and demand framework of AGRM. For this study, policy interventions in rice supply that are trade-distorting ("amber box" in WTO parlance) were removed. To place the impacts of the removal of domestic policies on rice trade in perspective, the model was also simulated for the removal of import tariffs and export subsidies as well. This exercise provides an additional analysis to evaluate the trade impact results generated by RICEFLOW, the spatial equilibrium modeling framework. Finally, the AGRM was used to examine the net effect of complete policy reform including domestic support, import protection and export subsidies.

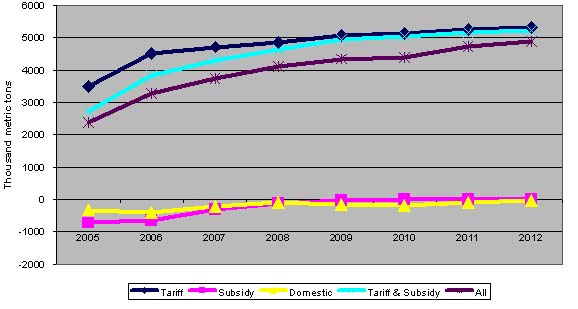

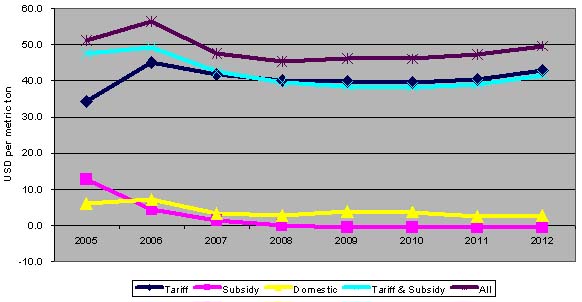

Results are presented in Figures 2-4. The AGRM baseline global trade projections are 27.9 mt in 2005 increasing to 33.6 mt by 2012. The world reference export price of long grain is the Thai 100 percent B and the reference export price for medium grain is the US California No. 2 Medium grain price. Long grain prices in the baseline begin at US$232/mt in 2005 and increase to US$277/mt by 2012. Medium grain prices increase from US$332/mt in 2005 and increase to US$406 by 2012.

The impact on global rice trade from the removal of tariffs dominates all policy reform scenarios. Trade increases by 3.5 mt in 2005 and continues to expand over time to 5.3 mt above the baseline. The removal of export subsidies reduces global rice trade in the short-term by 720 thousand mt but the effect in the long term is negligible. Taken together, removal of import tariffs and export subsidies, the effect on global rice trade is swamped by the tariff effects. Trade is higher in 2005 by 2.7 mt and by 2012 higher by 5.2 mt. Elimination of domestic supports in the United States, the European Union and Japan reduces trade very slightly and not at all over the longer term. The combined effect of the removal of tariff barriers, export subsidies, and domestic supports increases trade by 2.4 mt in 2005 and by 4.9 mt by 2012. The results of policy reform for an expansion of global rice trade by 15 percent given by the more aggregated but dynamic AGRM model is remarkably similar to the static results generated by the RICEFLOW model.

The impact on global export prices follows the impact on trade with the dominant impact on prices resulting from removal of import tariffs. The long grain price is higher in the short term by US$23/mt and in the longer term by US$43/mt. In the more highly protected medium grain market, tariff removal causes prices to be higher by US$291/mt in 2005 and by US$340/mt by 2012. The impact of removal of export subsidies is important only in the short term with long grain export prices higher by 6 percent and medium grain prices higher by 5 percent. The removal of domestic supports is negligible throughout the projection period. The aggregate effects of policy reforms, including tariffs, export subsidies and domestic supports is significant for both long grain and medium grain prices. Long grain export prices are higher by 18 to 22 percent. This result differs from the RICEFLOW model result for export prices. Medium grain prices are higher than baseline projections by 70 to 80 percent. This result is similar to the findings reported using the RICEFLOW model.

Policy Implications and Conclusions

The global rice economy has been and continues to be distorted by substantial government intervention. Unilateral reforms that have been adopted or are in process in the United States, the European Union, and Japan are important initiatives for the global rice economy. This study finds that the benefits of policy reforms on a global basis will benefit Japan, China, the United States, the European Union and Australia by large measures. Policy reforms are rarely zero sum as is suggested by the estimates given in this study.

Policy reforms to eliminate protection in the global rice economy are estimated in this study to result in an increase of economic welfare of over US$7.4 billion per year. Most of these gains can be achieved through the elimination of tariffs on imports. Consumers in importing countries gain US$32.8 billion while producers in importing countries lose US$27.2 billion. Importing country governments lose US$2.9 billion tariff revenue but gain US$2.7 billion by eliminating domestic supports. The net welfare gain to rice importing countries is estimated to be US$5.4 billion. Producers in exporting countries gain US$70.2 billion while consumers in exporting nations lose US$68.8 billion. Imports by the exporting countries result in a loss of tariff revenue of US$5.3 million and elimination of domestic supports saves US$598 million. The net welfare gain in importing countries is US$2 billion.

With global policy reform, total rice trade is estimated to increase by 10 to 15 percent. Prices received by exporters would be expected to be higher by 25 to 35 percent. Prices paid by importers would be expected to decline by 10 to 40 percent depending upon the type of rice. Rice trade, despite the expansion, would remain relatively thin. Complete policy reform, would result in an increase of rice trade from the current level of 6.5 percent of consumption to 8.4 percent by 2012. Thus, one of the major sources of world rice price instability is likely to remain after liberalization. Global rice stocks have also declined over the past three years by 30 percent. Thus, the ability of stocks to buffer supply shocks has been markedly reduced. The implications of global rice trade liberalization for lower income, net-importing countries that would become more reliant upon world rice trade are not attractive. Political and food security is likely to be reduced.

Medium grain rice is the most protected rice type. Consequently, policy reform would have its biggest impact on the countries that export and import medium grain rice. Japan is estimated to capture nearly 70 percent of the global economic welfare gains. Other developed countries such as the United States, Australia and the European Union who export medium grain rice would also be significant beneficiaries of trade policy reform.

Ironically, some countries that currently have little or no degree of protection are likely to be harmed from policy reforms. This result is due to the large country impacts that countries like Japan’ increased imports would have, increasing the demand for medium grain rice and thereby increasing world prices especially for medium grain rice. Countries, such as Turkey and Russia, which have imported medium grain rice with moderate levels or no protection, would experience higher prices as a result of the increased volume of medium grain imports by Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Benefits of removing moderate levels of tariff protection, as in the case of Turkey, are swamped by the price effect of free and expanded trade in medium grain.

The impacts of domestic support policy reforms in the United States and the EU are estimated to reduce rice exports by less than 5 percent in the initial years and have relatively no impact on trade in the longer term. Prices are estimated to be 5 to 10 percent higher initially but over the longer term the effect diminishes to zero. Multilateral and regional trade policy reforms achieved over the past decade have contributed to an expansion in rice trade and more stable prices. The achievements of the Uruguay Round Agriculture Agreement include the opening of the previously closed Japanese and Republic of Korean markets. Limits placed on domestic supports in the EU and the US and export subsidies in the EU have yet to have a significant impact on rice trade. Regional agreements such as NAFTA and MERCOSUR have increased western hemisphere rice trade. The prospects for the Doha Round of the WTO hinge to a great extent upon continuing the expansion of market access, reduction of tariffs, and limits on export subsidies that will be effective.

Continued trade policy reforms are important for the global rice economy and will have positive impacts on producers in exporting nations and consumers in importing countries. But reforms will result in losses to other market participants. The exercise of political power by specialized interests in protecting benefits from a policy distorted global rice sector cannot be underestimated. Therefore it is important to continue efforts to clearly measure and understand the consequences of protection and the benefits of moving forward.

References

Durand-Morat, Alvaro and Eric J. Wailes. 2003. RICEFLOW®: A Spatial Equilibrium Model of World Rice Trade. Staff Paper SP 02 2003. Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, Division of Agriculture, University of Arkansas.

Fuller, Frank, Eric J. Wailes, and Haryanto Djunaidi. 2003. Revised Arkansas Global Rice Model. Staff Paper SP 01 2003. Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, Division of Agriculture, University of Arkansas.

US$A PS&D. 2003. Production, Supply and Distribution Online. US$A, Foreign Agriculture Service. At http://www.fas.US$a.gov/psd/

Wailes, Eric. "Trade Liberalization in Rice." In Agricultural Trade Policies in the New Millennium, ed. P. Lynn Kennedy. Haworth Press, 2002.

Wailes, Eric. "Global rice trade, protectionist policies, and the impact of trade liberalization." In Global commodity trade and impacts of trade liberalization. World Bank. Forthcoming.

Figure 1. World rice trade and percent share of total

use.

Source: US$A, PS&D, 2003

Table 1. Rice trade liberalization results from RICEFLOW model, 2000

|

Rice Type |

Baseline |

Free Trade |

% Change |

|

|

Long Grain |

|

|

|

|

|

High Quality |

|

|

|

|

| |

Paddy |

|

|

|

| |

Quantity (MT) |

1 035 320 |

1 081 254 |

4.4% |

| |

Export Price (US$/MT) |

149.21 |

154.67 |

3.7% |

| |

Import Price (US$/MT) |

185.51 |

166.89 |

-10.0% |

| |

Brown |

|

|

|

| |

Quantity (MT) |

856 798 |

916 721 |

7.0% |

| |

Export Price (US$/MT) |

223.75 |

219.25 |

-2.0% |

| |

Import Price (US$/MT) |

363.32 |

250.64 |

-31.0% |

| |

Milled |

|

|

|

| |

Quantity (MT) |

7 495 594 |

7 704 482 |

2.8% |

| |

Export Price (US$/MT) |

225.97 |

225.58 |

-0.2% |

| |

Import Price (US$/MT) |

262.06 |

252.16 |

-3.8% |

|

Low Quality |

|

|

|

|

| |

Milled |

|

|

|

| |

Quantity (MT) |

8 084 093 |

9 149 728 |

13.2% |

| |

Export Price (US$/MT) |

177.05 |

188.70 |

6.6% |

| |

Import Price (US$/MT) |

248.19 |

213.09 |

-14.1% |

|

Fragrant |

|

|

|

|

| |

Milled |

|

|

|

| |

Quantity (MT) |

2 449 711 |

2 467 502 |

0.7% |

| |

Export Price (US$/MT) |

265.24 |

267.07 |

0.7% |

| |

Import Price (US$/MT) |

511.20 |

299.07 |

-41.5% |

|

All Long Grain |

|

|

|

|

| |

Quantity (MT) |

19 921 516 |

21 319 687 |

7.0% |

| |

Export Price (US$/MT) |

206.87 |

210.68 |

1.8% |

| |

Import Price (US$/MT) |

287.45 |

236.43 |

-17.7% |

|

Medium/Short Grain |

|

|

|

|

| |

Brown |

|

|

|

| |

Quantity (MT) |

483,063 |

1 162 478 |

140.6% |

| |

Export Price (US$/MT) |

271.80 |

814.47 |

199.7% |

| |

Import Price (US$/MT) |

1438.54 |

842.75 |

-41.4% |

| |

Milled |

|

|

|

| |

Quantity (MT) |

2 487 760 |

3 946 170 |

58.6% |

| |

Export Price (US$/MT) |

367.71 |

628.92 |

71.0% |

| |

Import Price (US$/MT) |

855.89 |

645.69 |

-24.6% |

|

All Medium/Short Grain |

|

|

|

|

| |

Quantity (MT) |

2 970 823 |

5 108 648 |

72.0% |

| |

Export Price (US$/MT) |

352.11 |

671.14 |

90.6% |

| |

Import Price (US$/MT) |

950.63 |

690.53 |

-27.4% |

|

All Rice |

|

|

|

|

| |

Quantity (MT) |

22 892 339 |

26 428 335 |

15.4% |

| |

Export Price (US$/MT) |

225.71 |

299.69 |

32.8% |

| |

Import Price (US$/MT) |

373.51 |

322.97 |

-13.5% |

Source: University of Arkansas, RICEFLOW Model. 2003.

Figure 2. Policy Reform of the Global Rice Economy: Net Impact on Trade

Source: Arkansas Global Rice Model, University of Arkansas. 2003.

Figure 3. Policy Reform of the Global Rice Economy: Net Impact on Thai 100% B Long Grain Price

Source: Arkansas Global Rice Model, University of Arkansas. 2003.

|

[9] L.C. Carter Professor,

Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, University of Arkansas,

Fayetteville, AR 72701 USA. [10] Professeur L.C. Carter, Département d'économie agricole et d'agro-alimentaire, Université de l'Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701 (ÉTATS UNIES). [11] L.C. Carter, Profesor del Departamento de Economia Agrícola y Agroindustria, Universidad de Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701 USA. [12] L.C. Carter Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701 USA. |