WHAT ARE THE EAF MANAGEMENT COSTS AND WHO WILL PAY?

The shift to EAF implies higher management costs - to cover the acquisition of broader information, additional planning and consultative decision-making processes, as well as wider scope in monitoring, control and surveillance. Although these costs may often be out-weighed by the long-term benefits of implementing EAF, the question of “who pays?” will often be important, especially in the shorter-term before the benefits of EAF for the ecosystem and stakeholders have been fully achieved.

The idea of the fishing industry paying some fishery management costs is increasingly accepted. However, the fact that EAF responds to wider societal needs requires an explicit policy on how the incremental management costs of EAF should be divided between the benefits derived by those dependent on fishing for food, livelihood and employment, and benefits to society at large. Where countries are given the task of managing global ecosystem goods and services, consideration may have to be given to whether management costs should be carried by the international community, rather than by the local stakeholders or the government of the State where the activity is taking place.

K.L. COCHRANE, FAO | Implementation of EAF requires the involvement of a wider range of stakeholders. This raises important new economic questions such as how the costs of implementing EAF should be divided between those obtaining direct benefits, such as the fishers, and society at large, which is also obtaining benefits. It also raises problems about valuation of benefits and whether valuation should be based on local, national or international preferences. |

In considering global ecosystem goods and services, such as biodiversity or conservation of endangered species, the issue arises whether valuation should be based on national or local preferences, or take into account the preferences of the citizens of other countries or the international community. It also needs to take note of goals expressed in international conventions. On the other hand, valuation based on what the most affluent citizens of the globe are willing to pay could result in policy prescriptions that are unfavourable to poor producers and consumers in developing countries. This has given rise to the call for establishing equivalency standards that take into account differences in wealth and the ability to provide alternative employment and income opportunities.

The appropriate tools to estimate the costs and benefits of EAF include bioeconomic and ecological-economic modelling. A useful cross-sectoral tool is integrated environmental and economic accounting. A System of Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounts (SEEA) provides a comprehensive framework to monitor and analyse the interactions between different sectors of the economy and their individual and aggregate impacts on the environment.

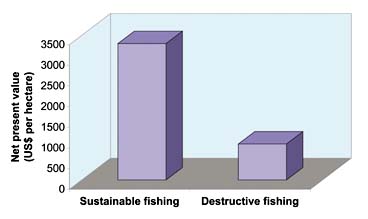

| The estimated value today (net present value) of the benefits that could be expected from a coral reef in the Philippines over the next 10 years with i) sustainable fishing practices and ii) using destructive fishing methods such as blast fishing (dynamiting). The benefits under sustainable fishing included those from the fishing itself but also included social benefits from coastal protection and tourism that would be lost with blast fishing. The analysis assumes a discount rate of 10% per year. From Balmford et al. Science Vol 297, 9 August 2002. |

|