Lake George Uganda

Lamberts (2004) describes how, for co-managed fisheries on Lake George, Uganda, catch data are compiled and shared through a network of stakeholders to provide an overall indication of the scale and significance of fisheries to the country. This information, when combined with others, is used to guide broad national planning and policy decisions. National catch data are transferred internationally to FAO where global catch data compilation is undertaken.

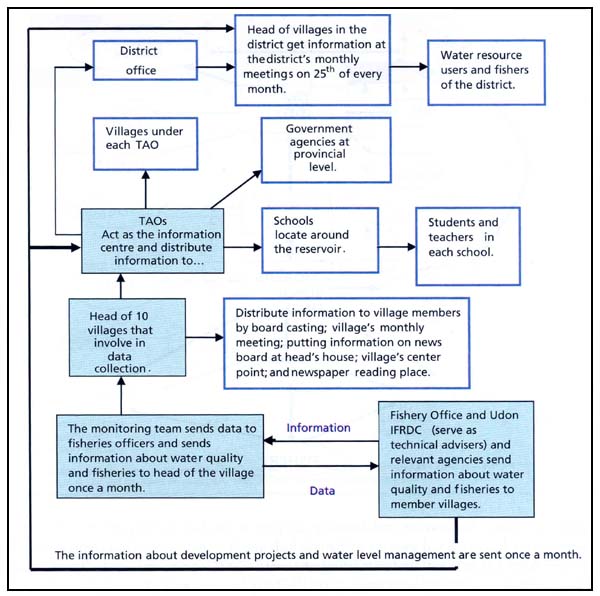

The catch, effort and price data are collected using Catch Assessment Survey (CAS) forms and initially processed at Beach Management Unit (BMU) level. This information is then forwarded from the Parish to the district level. At each level, the estimates are raised with an appropriate raising factor for each level or strata using the appropriate data collection form (Figure 19).

The sub-county fisheries officer serves as a transfer and collection point for information. The officer collects copies of CAS 1 (BMU-level) and CAS 2 (parish-level) forms by 15th of each month and completes a CAS 3 form to the district FO before the end of the same month. The district Fisheries Officer (DFO) then completes a CAS 4 form and submits that to district authorities and to DFR, Entebbe, by end of the same month. The Department for Fisheries Resources (DFR) produces synthesized information for the entire lake (CAS 5).

At each level, the data are used in the local government planning process, i.e., for the development of Parish Development Plans, Sub-county Development Plans and District Development Plans respectively.

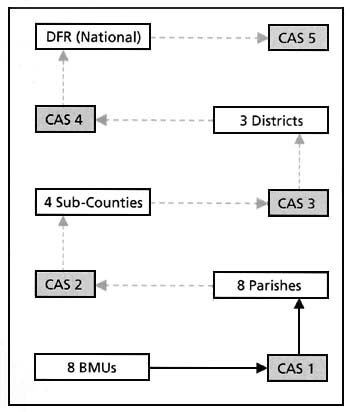

The District Fisheries Officer (DFO) coordinates the distribution of this information throughout his district and sends it to LAGBIMO -the Lake George Basin Integrated Management Organisation (LAGBIMO). The LAGBIMO Executive Secretary is responsible for compiling information at lake-wide level for planning purposes and sends it to the Fisheries Management Committee (FMC) members (Figure20). The FMC could also acquire this information from its BMU representative members. The outcome of the FMC meeting is distributed to the other committees in LAGBIMO.

The DFO also sends the information to the Department for fisheries Resources (DFR) as a contribution to the compilation of the state of fisheries in Uganda. DFR is then responsible for making policies, laws and plans based on the information collected. DFR then sends this information on to FAO, which uses the information for normative activities. The DFOs also send the information regarding their district to the Executive Secretary of LAGBIMO. There is, however, capacity to absorb and use data from other sectors that are currently underutilized. In part, this integrated management planning happens through the interaction with local government planning and monitoring, but this is still at an early stage, and the efficacy of the existing approach is yet to be assessed (Lamberts, 2004).

FIGURE 19

Data collection activities and actors on Lake George,

Uganda

Solid arrows indicate original data, dashed arrows indicate flow of synthesized information.

Source: Lamberts (2004).

FIGURE 20

Fisheries information flow and use in planning for Lake

George, Uganda

The greyed boxes indicate instances where data analysis and use in planning occur. The hashed box (DFO) indicates the level where data are stored and processed on computers. FPBC-Finance, Planning and Budgeting Committee. DFR-Department for Fisheries Resources.

Source: Lamberts, 2004.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh initiatives to network local community based organizations (CBOs) for inland capture fishery management established under various projects have shown that community organizations are interested to share and disseminate their knowledge and experiences through meetings, exchange visits and newsletters. After the first network meetings most of the involved CBOs contributed articles describing their management experiences for the CBO newsletter (Sultana, 2003).

For example, the RMC at Kali Nadi recognize the potential of newsletters for disseminating their ideas, knowledge and experiences. They also believe that the newsletter could be used to raise awareness among government institutions of their needs to improve the management of the river fisheries and lobby government institutions over management issues such as the creating of enabling legislation to support their management plans. What is apparent is that individual CBOs cannot easily network among themselves since they lack resources and contacts with similar initiatives. Some facilitation and funding support is needed to support this process. Networking has attracted interest in Bangladesh and has the potential to improve local management and national understanding of co-management activities and effectiveness when separate co-management units share their experiences and adjust decisions based on experiences in their own and similar communities and fisheries, and have a forum to interact with Department of Fisheries.

FIGURE 21

The information sharing network developed by stakeholders

at Sunamganj, Bangladesh

using a draft version of these guidelines

During the field testing of an earlier draft of these guidelines at eight sites in Bangladesh, stakeholders representing the Departments of Fisheries and Agriculture, partner NGOs (PNGOs), Community Based Organizations (CBOs), and other government bodies were able to use the eight-stage design process to design a preliminary data collection strategy to meet their information needs, and identify potential networks for sharing the information (Figure 21). It is hoped that these preliminary designs will be further developed and implemented to ensure that the information needs of local communities and government stakeholders can be sustained beyond the life of the CBFM and FFP projects.

Thailand

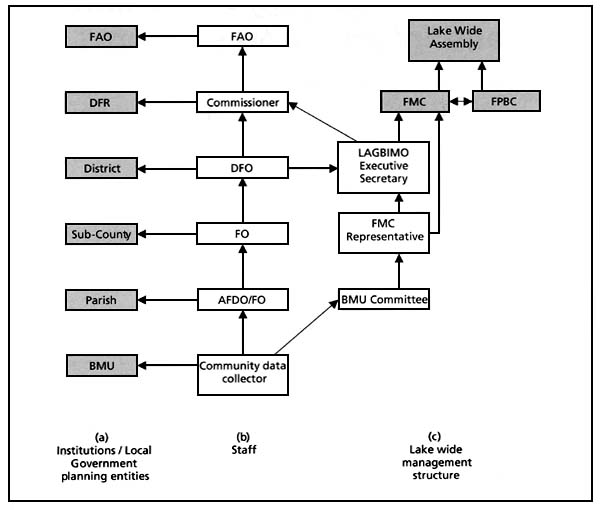

In Thailand, Or-Bor-Tor (OBT) or TAO -the local management institution, has a responsibility to facilitate information sharing between government officers and villagers. Village leaders share information with their people through loud-speaker and monthly meetings at the village level. Information sharing between fishermen is usually informal, or through the OBT (Hartman et al., 2004). In September 2005, a draft version of these guidelines were used to develop the data and information sharing system illustrated in Figure 22 to support the management of the Huay Luang Reservoir in Udon Thani, Thailand which is co-managed by the DoF and resource users from ten villages.

FIGURE 22

The information sharing system developed by co-managers of

the Huay Luang reservoir using a draft version of these guidelines