by

Wilfried Hundertmark, Senior Water Management Consultant

and

Sonia Tato, Technical Officer, IPTRID/FAO

Introduction

On the occasion of the 55th IEC Meeting of the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID) held in Moscow in 2004, the ICID Working Group on Capacity Building, Training and Education (WG-CBTE) organized a half-day workshop on capacity needs assessment in agricultural water management led by the International Programmeme for Technology and Research in Irrigation and Drainage (IPTRID). The event succeeded a workshop organized a year earlier in Montpellier, which focussed more broadly on capacity development in irrigation and drainage. A progressive approach appeared to be the right move towards more clarity of a concept that is widely discussed among development agencies involved in the water and other sectors, but hardly practised in irrigation and drainage management.

It is now increasingly recognised that capacity development in irrigation and drainage must be done strategically, in order to adequately respond to a rapidly changing environment both within and outside of the irrigation sector. It is also recognized that strategic planning and the implementation of capacity programmes must be aligned to a wider holistic strategic planning approach of the water sector, of which irrigation is an important part in most developing countries.

The very need for increased capacity in the field of water, irrigation and natural resources management was clearly recognised by the Ministerial Declaration of the 2001 Conference on Freshwater held in Bonn. Accordingly, increased capacity and technology transfer in developing countries, as well as education and training should be demand-oriented, participatory and hands-on. It should make use of information and communications technology, distance learning and institutional twinning. Training should bridge gaps between the disciplines and include participatory methods and the realities of the lives of the poor (Bonn, 2001).

The objective of this paper is to define a principal approach towards designing and implementing an Integrated Capacity Development Strategy in developing countries. The challenge is to propose a “how to” methodology rather than theoretical definitions and tools which are frequently repeated in similar documents. However, the task is less straightforward than one would expect. The nature of capacity development suggests that it evolves as an organic process of growth, promotion and organizational change which involves interaction with stakeholders and a change of attitudes, perceptions and behaviour of peoples (Kay et al. 2004). As the paper proceeds, difficulties and challenges will be discussed when passing from the theory to the practice. Eventually it is expected that the paper will contribute to the creation of an innovative draft of guidelines that will serve as an IPTRID methodology for successive engagements in Capacity Development (CD) in the developing countries.

Strategic capacity planning

Policy issues

International experience suggests that governments should ask some fundamental questions concerning irrigation capacity needs before launching a broad Capacity Development initiative. In fact, national authorities from developing countries should receive the support needed to create the adequate combination of goals, policies, strategies, investment commitments in order to make sure they are prepared to address a Capacity Development Programme. The extent to which capacity in irrigation and drainage development is needed depends largely on sector development priorities set by governments. Clearly, the existence of a functioning legal and regulatory framework appears to be a key institutional issue in the state's ability to guarantee good service delivery. The following policy issues need to be addressed by governments in order to identify priorities and allocate resources accordingly and more efficiently:

Planning framework

The design of a strategy and its formulation is a long process which involves a phased and multi-faceted approach. It implies that organizations involved realign their goals and policies, revise expected results, and adjust strategies and action programmes, as the Strategic Plan is implemented.

Strategic planning usually does not lead to a rigid plan but aims to create the conditions for a continuing flexible response. A strategy can be defined as a long-term plan of action which is designed to achieve a particular goal. It also involves the definition of objectives and resources allocation which are required in order to implement the plan. A widely applied approach in strategic planning is to examine the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the organization or system where a Capacity Development process is going to be developed.

For the development of a capacity development strategy, Kay et al. (2004) distinguished a five-phased approach which is presented as non-linear; its phases are interlinked and overlapped, and they form a continuing cycle of development and change according to the prevailing circumstances. In each step a fundamental but simple question is asked: Where are we now? Defining the present capacity within the system: Where do we want to go? Looking ahead to the future desired state, the vision of what capacity is required in the future in order to do the job: How do we get there best? Comparing the present situation and future desired state; identifying the capacity gaps and strategies and actions designed to fill these gaps and achieve the desired goals: What are the priorities? What actions do we take? Fulfilling the strategies and undertaking the planned capacity development activities in order to meet the defined objectives: How do we stay there? Monitoring and evaluation to feed back experiences into the planning phase.

The analytical process embraces a series of steps which set the foundation for the formulation of a comprehensive capacity development strategy.

Figure 1. Principal steps for the development of a capacity development strateg

Capacity needs assessment

It is now well established by the world's leading agencies engaged in Capacity Development, that the capacity needs assessment process involves three main dimensions. First, the enabling environment in which capacity is needed. This refers primarily to the policy framework, laws and regulations, and the institutional arrangements in the water and irrigation sector. Second, the organizations which are responsible for policy development, planning and project management. Typically, government agencies are organised across administrative boundaries and hydrological units, reaching from national to provincial and local levels. Organizations other than government organizations include international and national NGOs, the private sector and private-public partnerships, all of which provide valuable services to the irrigation development. Third, capacity needs of the individuals, which implies that individuals are being identified and grouped into homogeneous professional categories. Altogether, the assessment of capacity needs embraces a whole range of different administrative and organizational levels, functions and geographical dimensions.

As a part of their services for non-profit organizations, Mc Kinsey (2001) developed a generic matrix for organizational capacity assessment (grid). The grid can be adapted with some modification to the other two dimensions as shown in Table 1. The grid asks the reader to score the enabling environment, the organization or the individual by selecting the text that best describes its current performance. The grid may be used by managers, staff, board members and external capacity builders with the following objectives:

Table 1. Capacity needs assessment

| Capacity Benchmarks | ||||

| Capacity Dimension | (1) Clear need for increased capacity | (2) Basic level of capacity in place | (3) Moderate level of capacity in place | (4) High level of capacity in place |

| ENABLING ENVIRONMENT | ||||

| Policy framework | ||||

| Legal and regulatory framework | ||||

| Educational system | ||||

| Pay/incentive systems | ||||

| Technical assistance | ||||

| Networks | ||||

| ORGANIZATION | ||||

| Aspirations | ||||

| Strategy | ||||

| Organizational skills | ||||

| Human resources | ||||

| Systems and infrastructure | ||||

| Organizational structure | ||||

| Culture | ||||

| INDIVIDUAL | ||||

| Job skills and needs | ||||

| Values/attitudes/motivation | ||||

| Performance/incentives | ||||

| Relationships/interdependence | ||||

| Communication skills | ||||

| Cultural sensitivity | ||||

| Team spirit | ||||

| Language skills | ||||

Each component is described by four benchmark statements, which correspond to a capacity category which defines the capability to operate of an individual, organization, etc. according to the strategy:

Enabling environment

The analysis of the enabling environment for capacity in irrigation establishes how the transformation of society and the country's place in the world impact on the irrigation sector. The development of data, information and communication technology is an example for such external factors that have potential impact on the development of capacity. The needs assessment of the enabling environment involves further judgements on economic, social and other trends, and speculation on emerging threats and opportunities. It leads to the formulation of national goals, strategic directions and expected results which together guide the formulation of a capacity development strategy.

There are numerous examples on the impact of changing environments such as the creation of linkages between people and institutions across the world, and exchange of information and knowledge within networks and virtual discussion groups. Networks themselves have become powerful tools for capacity development of individuals and institutions around the world, in developed as well as developing countries (Cap Net, 2002).

As a baseline for the formulation of a capacity development strategy, a methodology known as institutional mapping, has attracted the interest of practitioners in irrigation and drainage. Institutional assessment seeks to draw a picture of an institutional landscape of organizations involved in the development of a sector. Institutions relevant to the irrigation sector are being identified, described and their performance assessed. Grouped by functions, a matrix depicts the functional and spatial coverage in the provision of services and functions (Mahmoud, 2004). IPTRID is currently carrying out an institutional mapping study under the project ESPIM (Evaluation Study of Paddy Irrigation under Monsoon Regime) which analyses the capacity needs at the organization level involved in irrigation related to paddy production; this will allow identification of both strengths and gaps of the existing capacities at the institutional level and set the stage for a full assessment at the national level.

Organization

By far the most difficult and complex capacity dimension concerns organizations and institutions. However, over the past twenty years or so much conceptual work has gone into the development of tools suitable to assess the capacity needs of organizations (DFID, 2002; DFID, 2003; and Horton, 2002).

The above matrix can be used as a tool to help non-profit organizations to assess their organizational capacity. Conceptually, the grid is based on seven elements of organizational capacity and their components, known as the Capacity Framework. The elements account for the organization's aspirations, strategy, organizational skills, human resources, systems and infrastructure, organizational structure and culture. Each capacity element is further broken down into several components. For example, components coming under “aspirations” include mission, vision clarity, vision boldness and overarching goals. Each component is described by four benchmark statements, which correspond to one of the four capacity categories described in Table 1.

Individual level

Individual capacities may include but not be restricted to job skills and needs, values, attitude and motivation, performance incentives, relationships, communication skills and team spirit (Kay et al., 2004). It is suggested that benchmarks are being developed based on existing job descriptions and needs.

While assessing the performance of individuals working within an organization, particular attention is to be given to motivation and the incentive systems in place. Experience from developing countries suggests that insufficient payment of civil servants involved in irrigation and drainage, and insufficient funding for operations and service provision are the most important constraints to good performance and job satisfaction.

Prioritization of capacity gaps

An important step in capacity needs assessment is the determination of what capacity is needed most in order to meet the desired purpose. Usually planners would develop a set of criteria which are suitable for identifying priority capacity needs, and which allow estimates of possible impact on the sector performance. The existence of a functioning legal and regulatory framework is the key capacity need for accelerated sector development. One indicative criterion may be poverty reduction and food security, the way natural resources are managed and the environment is preserved. Capacities which ensure the provision of financial and social support services would be another criterion for prioritization (Hundertmark 2004).

Programme design and formulation

General actions

The design and formulation of a capacity development strategy require clarity on fundamental actions involved in the proposed process, methodology and approach. Such elements include the following:

| Enabling environment → | Objectives → | Outputs → | Activities |

| Organization → | Objectives → | Outputs → | Activities |

| Individual → | Objectives → | Outputs → | Activities |

The vision

It is now a standard approach in project and programme management that a vision statement forms the starting point of a programme strategy development exercise. A vision statement describes in graphic terms where you want to be in the future. An effective vision statement is clear, unambiguous and it involves aspirations that are realistic. A vision should also be driven by the needs of beneficiaries and aligned with the organization's values and culture involved.

Developing a coherent basis for strategic choice

During the stage of capacity assessment we have established a range of priority needs at the various levels of analysis. However, the knowledge that capacity needs do exist does not automatically lead to possible strategies for capacity development. In many situations there are reasons other than identified which may constrain the development of capacity. Possible examples are restricted resource allocation, insufficient donor coordination, corruption and poor governance. In order to address the right issue within a capacity development strategy it is suggested that capacity assessment be combined with an in-depth problem and constraint analysis.

Capacity constraint analysis

It is a well-established approach in programme management to convert the identified elements of a problem tree into a set of related objectives (objective tree). In its simplest form, the objective tree uses exactly the same structure as the problem tree, but with the problem statements (negatives) turned into objective statements (positives). In this regard, stakeholders may provide some indication of what their priorities are. In a prioritization process, the identified problems can be ranked against four criteria: the geographical scale (local, provincial, national, international); its level of concern (low, medium and high); the ability to adequately address the issue (low, medium and high); and priority ranking (one to five with one being the most severe).

Analysis of alternative strategies (options)

There is no blueprint available which would be sufficient to fill a capacity gap. For example, technical assistance (TA) comes in a number of forms; long or short-term advisory support, consultancy assignments, formal or informal training, on-the-job training, work placements or attachments and mentoring (including long distance). The particular choice of TA instruments will be context specific. There are also choices to be made about how such TA is delivered. At the level of the environment, strategic options include policy reform, regulations, by-laws, educational system reform, etc. A recently presented study by UNESCO proposed a five-pronged approach to meet the needs for water-related education and training focusing on: i) the formative years; ii) vocational training; iii) university education; iv) continuous learning; and v) research capacity strengthening. Also, full advantage is to be taken of contemporary methods, which ensure that education fulfils the following criteria: (a) be learning-based, demand-oriented, quality assured, participatory and hands-on; and (b) make use of information and communication technology, distance learning and twinning.

Analysing strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats

Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats analysis (SWOT) is a standard methodology in strategic planning. It is a very useful tool for the assessment of organizations involved in the formulation of a capacity development programme. The SWOT analysis forms the basis of an in-depth investigation of the organizations and stakeholders. It should be mentioned that the output from the capacity assessment proposed in Chapter 3 can serve as an input for an indicative SWOT analysis. If we assume that opportunities and threats for the formulation of a capacity development strategy are mainly provided by the external environment whereas strengths and weaknesses reflect the internal affairs of the sector and the organizations involved.

Strategic directions

Usually, a capacity development strategy is composed of a number of objectives, which fall under distinct strategic directions, which form more general areas or themes of a general nature and importance. For example, for priority enabling environment issues to be addressed under the level one ‘enabling environment’ assume four strategic directions: policy and legal reform, institutional reform and decentralization, reform of the educational system and support of informal training facilities. Specific objectives are being formulated in conjunction with each of the identified priority issues objectives (see Table 2).

Table 2. Strategy formulation: strategic objectives for the enabling environment

| Strategic Directions (Themes) | ||||

| Level I: Enabling environment | Policy and legal reform | Institutional reform and decentralization | Reform of the educational system | Support of informal training facilities |

| Priority Issue | Objectives | |||

| Policy and legal framework | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 |

| Legal and regulatory framework | 05 | … | … | … |

| Educational system | … | … | … | … |

| Pay/incentive systems | … | … | … | … |

| Technical assistance | … | … | … | … |

| … | … | … | … | … |

| Networks | ||||

Programme implementation

Action-oriented approach

Up to this point, the paper has covered all the major steps in the strategic part of the planning process. It has dealt with the environment, the organizational and with the individual levels. It has shown a way as to how to draw certain conclusions about capacity gaps and issues and it has proposed strategic options and directions for dealing with them. As a result, we have proposed an integrated matrix which shows an action-oriented plan with the steps to be taken during the strategic planning process, the key actions, level of intervention, main actors, tools and resources (human and economic), time schedule and a definition of milestones to be accomplished.

Table 3. Action plan for the enabling environment

| Action Plan | ||||||

| Level I : Enabling environment | Key actions | Level of intervention | Main actors | Tools & resources | Time schedule | Milestones |

| Stage | ||||||

| Inception phase | ||||||

| Programme formulation phase | ||||||

| Programme implementation phase | ||||||

| Evaluation, monitoring | ||||||

The identified strategic objectives in Table 2 should correspond to the activities proposed for intervention which are displayed in Table 3 (action plan). Similar action should be expected for other dimensions according to the appropriate aspects to be examined.

Establishing a coordinating body

In order to implement a capacity development strategy it is of major importance that a coordinating body be established, either within or outside the main line agencies involved in irrigation. The body would be charged with the coordination of the strategy implementation process and oversee the specific actions at the various levels. The existence of the body will also be subject to the extent of the exercise. The body would help to focus on the priorities established according to the goals and mission of the Capacity Development Programme. Other responsibilities would include the facilitation of capacity development projects and their promotion to the interested funding agencies. Consequently, it would oversee activities that deal with the public domain, including donor relations, communications, as well as the involvement of stakeholders from both the irrigation community and civil society.

In practical terms the body would have to arrange for the elaboration of a detailed action and annual work plans in order to ensure that the right processes are being carried out and the right resources are available to efficiently implement the strategic plan. An important role of the body would involve the establishment of a suitable evaluation and monitoring system based on a set of appropriate indicators, which are suitable to monitor the progress of programme implementation and its impact on the primary stakeholders and beneficiaries.

Strategic partnerships

The implementation of a comprehensive Capacity Development Programme would not be possible without the knowledge and the expertise of specialized organizations from the international, national, non-profit and non-governmental domains. International organizations in the field of water management and irrigation such as IPTRID, IWMI, ICID and UNESCO, provide capacity development services to the benefit of countries. At the regional level organizations such as NEPAD provide scope for regional integration of capacity development initiatives. Within countries, strategic partnerships may include public-private and public-non-governmental forms. Key to the success of a partnership is trust and mutual interest.

Funding

The main responsibility for resource allocation and proper funding usually lies with the government. However, given tight budgetary constraints of many developing countries, the implementation of a Capacity Development strategy cannot be done without the support of donors and other sources of funding. Donors usually provide technical assistance in the form of expertise in technical and process-oriented matters by taking on specific programme components. Increasingly, donors tend to provide budgetary support with limited interference in the technical domain. The critical elements of donor support of a Capacity Development strategy are trust, transparency and accountability of the actors involved in the process.

Evaluation and monitoring

The existence of functional and efficient evaluation and monitoring systems is critical for ensuring sustained interest and commitment in a Capacity Development programme. Elements of such a system include performance and impact indicators, an established data, information and knowledge base and coordinated processing and interpretation procedures. The establishment of suitable capacity performance and impact indicators poses a formidable challenge. In a worked example of a log frame matrix, IFAD (2004) provides some ideas on how to express capacity development objectives and how to monitor them. Accordingly, performance indicators are put forward as a performance question, which is complemented by a set of indicators and targets. For example,

Output: Capacity strengthened of department of agriculture to support local development process.

Performance questions: How successful has the department of agriculture been in facilitating agricultural and economic development in the province? How satisfied are key clients with the service and support of the department?

Indicators and targets: All staff with revised job descriptions, performance targets and work plans; management structures, 75 percent of staff adequately carrying out their work plans and meeting performance targets.

Monitoring mechanisms: Activity and performance monitoring system established within department; interviews with key clients (farmers, businesses, NGOs); organization assessment of the department activity (baseline, mid-term, and three years after completion; participatory impact monitoring with farmers groups).

Assumptions: Department will play a key role in the development process; the department will be able to re-orient towards being client-oriented, and working in partnership with other stakeholders including the private sector.

It is expected that IPTRID will, once again, support jointly with the Capacity Building, Training and Education Working Group, another ICID international workshop. It will be held in Malaysia and will complement the past events by presenting the final stage of the Capacity Development process titled “Monitoring and evaluation of Capacity Development Programmes”.

Conclusions

In this paper we focus on the design and the formulation of a Capacity Development strategy in the field of irrigation. Capacity development initiative by nature requires a strategic approach which responds to particularities of the subject as being soft, long-term, multi-dimensional, multi-layered, dynamic incorporated and connected to other strategies of the water sector. The proposed approach is based on strategic planning, which is process and action-oriented. It is divided into six stages which form a logical cycle of capacity needs assessment, programme formulation and implementation to monitoring and evaluation. As entry point we suggest the clarification of the purpose for which capacity is needed. Strategic alignment of a capacity development strategy is identified, among others, as a fundamental issue that governments need to address. Other issues include willingness to reform and organizational change.

Within the proposed strategic planning framework we deal with the enabling environment, the organizational and the individual level capacity and show how to draw conclusions with regard to strengths and weaknesses, opportunities and threats. We propose a strategic planning matrix which is complemented by a pragmatic action plan matrix containing key actions at various levels and dimensions. The matrix is conceived as an innovative tool for guiding systematic and comprehensive capacity development interventions. Implementing a capacity development programme requires a coordinating apex body with oversight for the achievement of the objectives to make sure that everything is happening as expected, programmatic cohesiveness and adequate funding. Performance and impact monitoring systems are vital for sustaining the interest, support and commitment of both governments and donors in a successful Capacity Development Programme.

References

ADB (2004) Strategic options for the water sector (T.A. 2817-PRC); Draft final report.

Bryson, John M. (1995). Strategic Planning for Public and Non-profit Organizations: A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organizational Achievement. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0787901415.

Cap-Net (2002). Capacity building for integrated water resource management; the importance of local ownership, partnerships and demand responsiveness. www.cap-net.org.

DFID (2002a). Capacity development: where do we stand? Department for International Development, Governance Division .

DFID (2002b). Tools for Development: A handbook for those engaged in development activity. Performance and Effectiveness Department, Department for International Development.

DFID (2003). Promoting institutional and organizational development. A source book for tools and techniques. Department for International Development, London, UK.

GTZ (2003). Capacity development. Policy paper no. 1. Strategic Corporate Development Unit Policy and Strategy Section, Gesellschaft fuer Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ), Eschborn Germany.

Horton, D. (2002). Planning, implementing and evaluating capacity development. Briefing paper no. 50, International Service for National Agricultural Research (ISNAR), The Hague, The Netherlands.

Horton, D.; Alexaki, A.; Bennett-Lartey, S.; Brice, K.N.; Campilan, D.; Carden, F.; de Souza Silva, J.; Duong, L.T.; Khadar, I.; Maestrey Boza, A.;Kayes Muniruzzaman, I.; Perez, J.; Somarriba Chang, M.; Vernooy, R. and Watts, J. (2003). Evaluating capacity development: experiences from research and development organizations around the world. The Netherlands: International Service for National Agricultural Research (ISNAR); Canada: International Development Research Centre (IDRC), the Netherlands: ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA).

Hundertmark, W. (2004). Strategic options for capacity assessment in agricultural water management: design and management of the process. IPTRID/FAO Workshop proceedings on capacity development in agricultural water management. 55th IEC Meeting of the ICID, Moscow.

IFAD (2004). Managing for impact in rural development: a guide for project M & E. Annoted example of logframe matrix.

IWMI (2003). Irrigation management transfer: How to make it work for Africa's smallholders? Water Policy Briefing. Issue 11, International Water Management Institute.

Kay. M.; Franks, T. and Tato, S. (2004). Capacity needs assessment in agricultural water management: Methodology and processes. ICID Workshop on Capacity Needs Assessment, Moscow.

Mahmoud, I.M. (2004). Institutional mapping to assess capacity needs for the development of water boards at district level in Egypt. In: Workshop proceedings on capacity development in agricultural water management, The 55th IEC meeting of the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID). Final report; IPTRID/FAO, Moscow 2004.

McKinsey (2001) Effective capacity building in non-profit organizations. Prepared for Philanthropy Partners by McKinsey & Company.

UNDP (1997) Capacity development. Technical advisory paper 2.

UNESCO: Towards a strategy on human capacity building for integrated water resources management and service delivery. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001262/126258eo.pdf

Annex 1. Strategic planning case from the Peoples Republic of China (PRC)

In the following a case from an ADB-funded strategic planning project in the People's Republic of China is being reproduced, in order to demonstrate a real world approach in strategic water sector planning (ADB, 2004). The approach taken evolves in seven steps, one for the analysis of the external environment and six focussing on the internal sector environment. It comprises three main stages: First, an analysis of the context surrounding the water sector (the external environment) (Step 1); second, the analysis of the water sector itself (the internal environment, steps 2, 3 and 4); and third, representative outputs that simulate what the government might conclude if it was to adopt such a process in full (Steps 5, 6 and 7).

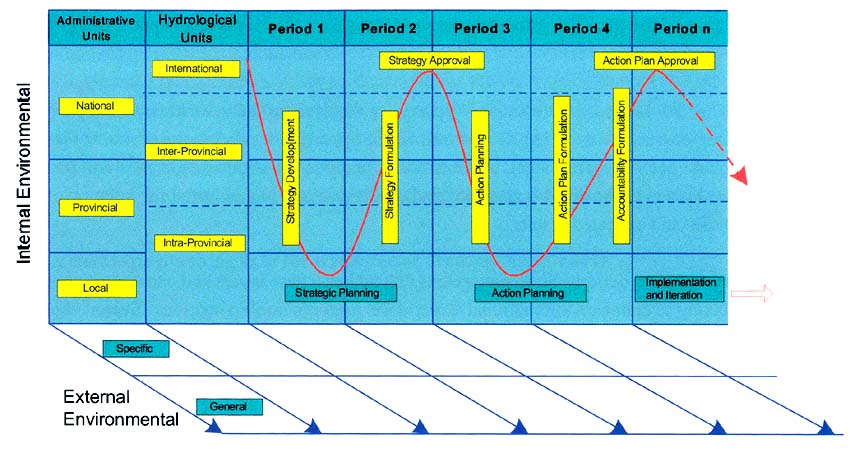

Figure 2. Strategic planning case for water sector (Source: ADB, 2004)

Step 1: Analysis of the external environment. The analysis of the external environment establishes how the transformation of society and the PRC's place in the world impact on the water sector. It involves judgements on economic, social and other trends, and speculation on emerging threats and opportunities. Taking account of the principles that must govern water management, it leads to the formulation of national goals, strategic directions and expected results which together guide the formulation of a water sector strategy.

Step 2: Assessment of the physical resource base. The analysis of the water sector's internal environment assesses its capacity to respond to events and issues that are identified in the external analysis. It begins with an evaluation of the physical resource base, and documents trends and prospects in the use and abuse of the resource itself.

Step 3: Analysis of the internal strengths and weaknesses. Analysis of the internal environment goes on to identify strategic issues, and to analyse constraints and opportunities facing the sector. It focuses on structural, financial, technological, legal, organizational, analytical and other capacities and potentials, leading to an evaluation of the sector's strengths and weaknesses, and to an initial formulation of sector objectives, policies and expected results.

Step 4: Defining strategic options. Strategic options that address these issues and constraints are defined and assessed taking account of international experience in comparable situations. Sector objectives, policies and expected results are adjusted in subsequent iterations.

Step 5: Prioritisation of options: Goal setting and analysis leads to the selection by decision-makers of preferred options that address each of the major issues, and a particular strategy is defined and adopted (summarized in the Strategic Planning Framework).

Step 6: Defining time-bound and measurable actions. The preferred strategy is translated into time-bound actions, programmes and projects that are measurable in terms of performance and results (summarized in the Action Planning Framework).

Step 7: Monitoring and evaluation. A programme for monitoring, evaluating and reporting on performance and results is prepared to be utilized during implementation (summarized in the Accountability Framework).

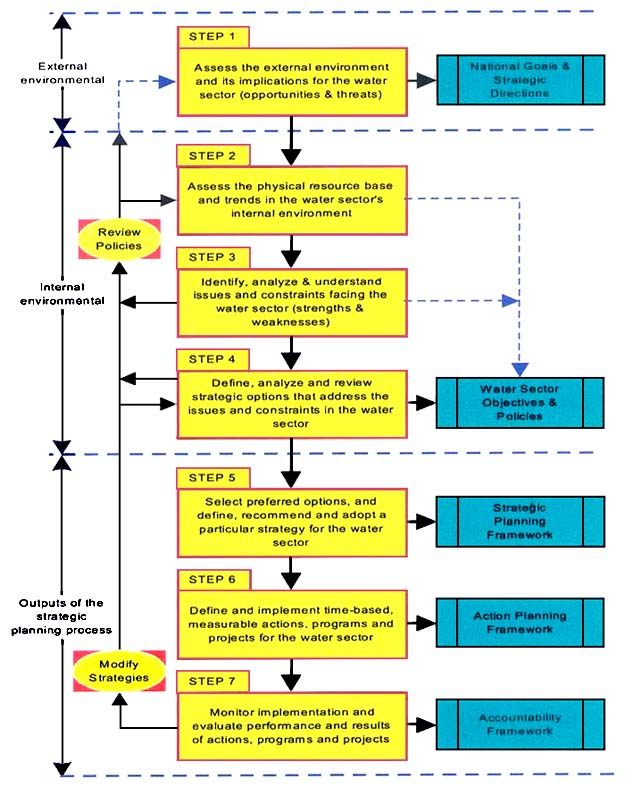

Strategic water sector planning stages normally evolves over several periods each comprising of planning activities at different administrative and hydrological levels (see Figure 3). The strategic planning phase, which is further divided into strategy development and formulation is followed by action planning stages.

Output:

Figure 3. Strategic planning in layer sectors and organizations