D. Kneeland

Douglas Kneeland is Chief of the Forestry Information and Liaison Service, FAO Forestry Department, and Chair of the Unasylva Editorial Advisory Board.

Despite diminishing public resources and growing demands, FAO strives to evolve to remain relevant in the world of forestry.

|

| FAO supports member countries in the sustainable management of trees and forests by putting information within reach, sharing policy expertise, providing a meeting place for nations and bringing knowledge to the field |

FAO celebrated its sixtieth anniversary in 2005 with a ceremony held on World Food Day, 17 October (see Box). Forestry has been included in the mandate of FAO since its inception in October 1945. But the original Forestry and Forest Products Division, the precursor of today’s Forestry Department, initiated its work in late spring 1946 – so FAO Forestry observes its sixtieth anniversary in 2006.

When FAO celebrated its fiftieth birthday, an entire issue of Unasylva was devoted to forestry in FAO during the first 50 years (FAO, 1995). The current article briefly recalls those first 50 years and offers a few observations on developments in the subsequent ten years.

The FAO forestry mission is to enhance human well-being through support to member countries in the sustainable management of the world’s trees and forests (FAO, 2000a). As in all the areas of its mandate, FAO provides this support through four main types of activity (see www.fao.org/UNFAO/about):

FAO is committed to support member countries in implementing sustainable forest management through participatory processes that link global, regional and national efforts. FAO works through partnerships with countries, universities, research institutions, international organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector.

Celebration of FAO’s sixtieth anniversary The Presidents of Brazil, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Italy, Paraguay, Slovenia, Venezuela and Zimbabwe were among the honoured guests marking the sixtieth anniversary of FAO at an official ceremony held on World Food Day, 17 October 2005.1 Founded in 1945 in Quebec City to free humanity from hunger, FAO has had an active role in increasing food production to meet the needs of a global population that has tripled since its creation. The anniversary ceremonies in Rome were highlighted by the award of the Organization’s prestigious Agricola medal to President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil. The award recognized President Lula’s Zero Hunger campaign, perhaps the most ambitious current national effort in the world to fight hunger and poverty. In his address on this occasion, FAO Director-General Jacques Diouf commented on the main achievements of the Organization, noting that “since 1960, the proportion of the world’s population that is undernourished has fallen from 35 percent to 13 percent”. He stressed the importance of FAO as a neutral forum where nations can come together to address food and agricultural issues. Looking towards the future, Mr Diouf noted that FAO “must address two central issues as the twenty-first century unfolds. First, it must increase the effectiveness of its work with its members towards eradicating hunger, as reflected in the first Millennium Development Goal. Second, it must foster the satisfaction of future global needs for food and forest products without compromising the sustainability of the earth’s fragile natural resources or its climate.”

1 World Food Day is observed annually on 16 October; in 2005, this fell on a Sunday. |

The first 15 years were an exciting time for forestry at FAO. Virtually every activity was pioneering in nature. Global forest assessments, forest product statistics, Unasylva – each current major area of work had its origins before 1950. Early on, it was recognized that much of the forestry work in FAO was regional in nature; six Regional Forestry Commissions were established before 1960, and Regional Forestry Officers were appointed in the regional offices. The programme emphasis in the early years was to ensure a sustainable supply of wood throughout the world in the period following the Second World War, especially in war-ravaged areas where reconstruction was an immediate priority.

During the period between the late 1950s and the early 1990s, the field programme was a strong component of FAO’s work. FAO executed over 1 000 forestry field projects in over 100 countries. Hundreds of forestry institutions have been started, developed or strengthened through FAO projects, including national and local forestry agencies, forestry colleges and technical schools, research institutes, forest tree seed centres, nurseries, sawmills and a wide range of community-based enterprises. An example is the Arab Institute for Forestry and Range in the Syrian Arab Republic, which has graduated more than 2 200 forestry technicians from all over the Near East Region since it was founded in 1954 with FAO support.

It is difficult to find foresters from developing countries who have not benefited from the FAO field programme, perhaps by attending a school or participating in a study tour supported by FAO, participating in FAO workshops, Regional Forestry Commissions or expert consultations, or working with an FAO project. The field programme also helped to keep otherwise desk-bound FAO staff linked to the real world.

In the 1960s, many FAO forestry projects provided technical assistance to support traditional forestry development, including harvesting, sawmilling and woodworking. In the 1970s, the emphasis shifted towards rural development. By the 1980s, FAO was leading a global trend of increasing support for community forestry, emphasizing local participation. By the 1990s, virtually the entire FAO field programme supported community forestry, rural development and participatory approaches to national forest policy development (Muthoo, 1995).

During the same period, there was a gradual but powerful shift from an emphasis on forest production towards a balanced approach giving equal weight to forest conservation and protection. Programmes were established to protect fragile ecosystems, to conserve forest genetic resources, to promote agroforestry systems and to combat forest insect pests and diseases.

In the past ten years, the supervision of the field programme has been devolved to a great extent to the regional offices, while headquarters programmes have focused more on normative functions. But FAO has continued to support countries in institutional strengthening and capacity building, through approaches that have steadily evolved. Current work centres on the development and implementation of effective national forest programmes, including policy and legal reforms and an increasing emphasis on strengthening domestic forest law enforcement and governance. With the broadening of the concept of sustainable forest management, the FAO field programme has increasingly emphasized the balance between the economic, social and environmental dimensions of forests.

As development assistance has devolved towards national execution and as institutions and expertise in developing countries have increased, the number of international FAO staff assigned to field projects has declined from over 300 professional forestry officers in the field in the early 1990s to fewer than 30 today.

However, FAO still supports the development of forest policies or institutions in more than 60 countries, and the annual budget of the forestry field programme continues to exceed the regular programme forestry budget. Increasingly, FAO inputs are provided through short field visits, mobilization of national expertise, increased South-South collaboration and partnership programmes, including those with broad objectives such as reducing poverty or reforming national policies. The goal of current FAO reforms is to increase greatly the percentage of regular FAO staff located outside headquarters.

| It is difficult to find foresters from developing countries who have not benefited from FAO field activities – such as this training-for-conservation workshop on nursery operation techniques in Nepal |

|

| FAO/FO-0088 |

| By the 1990s, virtually the entire FAO forestry field programme supported community forestry, rural development and participatory approaches to national forest policy development (shown, participatory planning exercise in the Upper Piraf watershed, Bolivia) |

|

| FAO/FO-0057 |

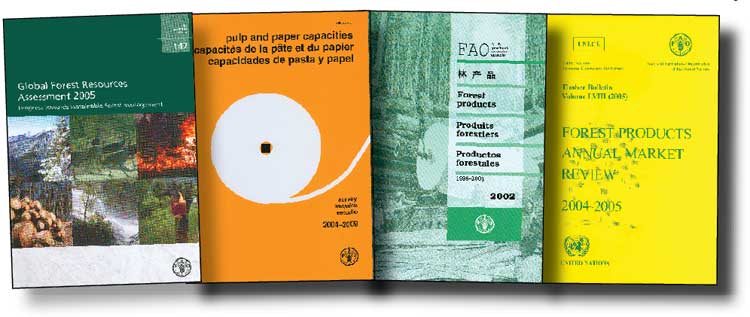

If field activities are the soul of FAO forestry, then forest assessments and statistics are the heart. The first paragraph of the Constitution of FAO states: “The Organization shall collect, analyse, interpret and disseminate information relating to nutrition, food and agriculture. In this Constitution, the term ‘agriculture’ and its derivatives include fisheries, marine products, forestry and primary forestry products.” (FAO, 2000b). From its inception FAO has had a mandate to monitor, assess and report on the world’s forests and world forestry. Forestry and forest products: world situation 1937–1946 (FAO, 1946) and Forest Resources of the World (FAO, 1948) were two of the early reports.

During its first 60 years, FAO has published nine global outlook studies and nine regional studies related to forests. Five regional forest sector outlook studies have been completed in the last 11 years alone. A side benefit of these studies has been the training of hundreds of national correspondents in the use of state-of-the-art methodologies, contributing directly to national institutional strengthening.

Annual statistical reports include the FAO Yearbook of Forest Products (published each year since 1945); Timber Bulletin (ECE/FAO), 1948 to present; Pulp and Paper Capacities (1959 to present); and a number of other regular series providing information on forest products prices, trade flows and recycled paper, to name a few.

FAO has published global assessments of forest resources on a regular basis, including the reports for 1948, 1953, 1958, 1963, 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2005, as well as interim assessments in 1988 and 1995. These global assessments have been supplemented by regional assessments and special studies of forest resources in tropical, temperate and boreal forest ecosystems. In addition, FAO’s programme to support national forest assessments helps countries build their capacity to assess their own forest resources; the number of countries benefiting from this programme is limited primarily by scarce resources rather than by demand.

A key development of the past ten years is the State of the World’s Forests, which has been published every two years since 1995 – concurrently with the meetings of the FAO Committee on Forestry (COFO), which brings together the heads of the world’s national and international forestry organizations.

| The field programme has become increasingly decentralized, with supervision devolved to regional and country offices (shown, the FAO country office in Uruguay) |

|

| FAO/G. ALLARD |

The most controversial activity in the history of forestry in FAO was the Tropical Forestry Action Plan (TFAP). Launched in 1985 by FAO together with the World Bank, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the World Resources Institute (WRI), TFAP called for a major international investment to save the tropical forests (FAO Committee on Forest Development in the Tropics, 1985). To obtain the financial support promised by the TFAP sponsors, a tropical country had to commit to undertake a complex national planning process and to transform its forest policies and programmes in accordance with TFAP guidelines.

Only a few years after it started, TFAP came under heavy criticism (FAO, 1990). From the viewpoint of many tropical countries, TFAP failed to deliver the anticipated increase in forestry investments. Environmental groups accused TFAP of promoting logging and failing to involve civil society (Colchester and Lohmann, 1990). Some observers critiqued that TFAP required countries to implement a top-down national forestry plan, which was out of step with the transition away from central planning at the time. The TFAP founding partners began to have disagreements, and by the time of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in 1992, the programme had become obsolete.

In the “Forest Principles” negotiated at UNCED (United Nations, 1992) and in follow-up venues such as the biennial meetings of COFO, the first Ministerial Meeting on Forests convened by FAO in 1995 and the Intergovernmental Panel on Forests (IPF) convened by the United Nations in 1995, consensus emerged that effective policies and programmes developed by countries themselves were the key to sustainable forest management.

The concept of national forest programmes replaced TFAP. IPF’s first “proposal for action” in 1997 called for countries to strive for sustainable forest management by implementing comprehensive policies through participatory processes that address issues across sectors (ECOSOC, 1997). The emphasis on national forest programmes has resulted in many national initiatives to reform forest policies and programmes. For example, in Africa 25 countries have developed new national forest laws or significantly revised existing ones during the past ten years. More than 100 countries, including most tropical countries, are implementing national forest programmes.

New mechanisms have been developed to provide support to national processes, including the innovative National Forest Programme Facility hosted by FAO. The Facility provides grants to NGOs in developing countries through partnerships that are designed to foster participatory processes in national forest programmes.

The irony is that the lessons already learned by tropical countries and FAO during the transition from the TFAP to national forest programmes seem to be lost at the international political level. Policy-makers continue to argue about top-down approaches to forestry. Not surprisingly, some have recently concluded that not all forestry problems can be solved at the global level, and that perhaps national or regional mechanisms would be more effective. For FAO, this sounds like déjà vu.

| Forest assessments and statistics are the heart of FAO forestry |

|

| New mechanisms developed to provide support to national processes include the National Forest Programme Facility, hosted by FAO – shown, the Facility Web site, disseminating information to countries |

|

The interface between forests and agriculture is one of the major issues facing FAO at 60. FAO is playing an increasingly important role in global efforts to reduce poverty, hunger and deforestation.

Yet landowners and governments often get a greater return on their investment if they convert forest land to other uses. The problem is often made worse by “negative incentives” which result in deforestation in developing countries. For example, the conversion of huge areas of the Brazilian Amazon for cattle grazing, and the concern that large cattle ranchers are growing rich meeting the international demand for Brazilian beef – sometimes called the “hamburger connection” (see Smith et al., 1995) – continue to draw world attention (Kaimowitz et al., 2004). To many tropical countries, the struggle to increase agricultural production and reduce deforestation may seem like swimming against the macroeconomic tide of history.

Conflicts between forests and agriculture will continue to be among the most important issues to be addressed by FAO in the years ahead. FAO sponsored a seminar on this topic at COFO in 2005, and FAO is the obvious international organization to take the lead on the interface between the two sectors because of its mandate as the United Nations agency responsible for both sectors.

| Clearing for agriculture in the hills of Viet Nam: the interface between forests and agriculture is one of the major issues facing FAO at 60 |

|

| FAO/FO-0136/C. PALMBERG LERCHE |

A significant trend in FAO forestry in recent years has been the development of best practices or codes of practice.

The idea of best practices is not new. FAO has published field guides and manuals for the management and conservation of forests for more than 50 years. In the past 15 years, FAO and another key partner, the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) have developed a range of codes, guidelines and principles that cover a broad range of activities in the forest sector (see Box).

The debate continues at the global level about whether codes should be legally binding or voluntary. In the interim, organizations such as FAO and ITTO continue the practical work of developing these codes. Increasing numbers of countries and private companies are implementing forestry codes and guidelines, either through national policies or legislation or through less formal processes.

In the past ten years, one of FAO’s partners, the International Model Forest Network, has grown to include almost 40 model forests in 18 countries (International Model Forest Network, 2005). Building on the model forest idea, a recent FAO initiative in Africa, Asia and the Pacific and most recently in Latin America, “In Search of Excellence”, identifies examples of well-managed forests with the goal of sharing experiences with other countries (FAO, 2003, 2005a).

Forest-sector codes, guidelines and principles of FAO and ITTO FAO

ITTO

Joint

1 A consultative process involving countries, civil society and the private sector is under way with the goal of approval by COFO in 2007. 2 A consultative process to develop guidelines or a fire code in collaboration with the UN International Disaster Relief Committee (IDRC) is under way with the goal of approval by COFO and by an International Wildland Fire Summit in Spain in 2007. |

In fulfilment of its constitutional mandate as a neutral forum for policy dialogue, FAO has organized the past eight World Forestry Congresses; 127 meetings of the six Regional Forestry Commissions; 17 sessions of COFO (attended by 90 national Heads of Forestry in March 2005) (see Unasylva 220 [FAO, 2005b]); and literally hundreds of international workshops, expert consultations and seminars related to forestry in over 100 countries, at all levels from grassroots to scientific and technical high-level. FAO has also organized three Ministerial Meetings on Forests which have helped to elevate the importance of forests on the global political agenda.

The Regional Forestry Commissions and COFO serve as venues for countries to share their experiences on a regular basis. Increasingly, the Regional Forestry Commissions are sponsoring regional initiatives covering a broad scope of action, such as regional networks to address fire management, invasive species, financing for sustainable forest management and other issues of mutual interest to countries in the same region (see Koné et al., 2004). These processes are reaching out to other sectors and inviting civil society representatives to participate in regional dialogue.

One of the most important developments during the past ten years has been the creation of the innovative Collaborative Partnership on Forests (CPF), which FAO chairs. CPF was established to support the international arrangement on forests, including the United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF). Currently comprising 14 international organizations, CPF is exploring new ways for organizations with mandates or interests related to forests to work together to avoid duplication and to achieve synergies, for example through harmonized and consolidated reporting.

Public resources to support forestry are increasingly scarce, while the demands are growing. Few countries will indefinitely support processes that fail to produce results. The FAO Forestry Department is committed to ensuring that every international meeting that it organizes has a clear purpose and objectives, and that every effort is made to achieve results that benefit its member countries.

Forests grow and evolve slowly over centuries, but forestry is a dynamic sector that has changed significantly over the past 60 years in line with national and global views and needs.

As the United Nations organization with the mandate for forests and forestry, FAO and its staff have worked hard to keep up with the evolution of forestry and to provide global leadership. FAO staff have worked for national or local forestry agencies, NGOs or research institutes, have taught at forestry colleges or universities, or have worked for forest products companies or their own businesses. They come from every continent and over 30 different countries. FAO is its member countries.

FAO is working hard to remain relevant in the world of forestry by responding to the priorities established by its members. FAO staff are committed to the challenge of helping to shape and respond to change. FAO plans to continue to fulfil its historic mandates, to lead CPF and to serve FAO member countries.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Colchester, M. & Lohmann, L. 1990. The Tropical Forestry Action Plan: What Progress? Penang, Malaysia, World Rainforest Movement.

Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (ECOSOC). 1997. Report of the Ad Hoc Intergovernmental Panel on Forests on its Fourth Session, New York, USA, 11–21 February 1997. E/CN.17/1997/12. New York.

FAO. 1946. Forestry and forest products: world situation 1937–1946. Washington, DC, USA.

FAO. 1948. Forest resources of the world. Unasylva, 2(4). Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/x5345e/x5345e00.htm

FAO. 1990. The Tropical Forestry Action Plan: report of the independent review, by O. Ullsten, S.M. Nor & M. Yudelman. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

FAO. 1995. Unasylva, 182. Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/v6585e/v6585e00.htm

FAO. 2000a. FAO Strategic Plan for Forestry. Rome. Available at: www.fao.org/forestry/site/1961/en

FAO. 2000b. Basic Texts of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome. Available at: www.fao.org/DOCREP/003/X8700E/x8700e00.htm

FAO. 2003. Sustainable management of tropical forests in Central Africa: In search of excellence. FAO Forestry Paper No. 143. Rome. Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/006/y4853e/y4853e00.htm

FAO. 2005a. In Search of Excellence: exemplary forest management in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok, Thailand. FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/007/ae542e/ae542e00.htm

FAO. 2005b. COFO 2005 – dialogue into action. Unasylva, 220. Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/008/y6006e/y6006e00.htm

FAO Committee on Forest Development in the Tropics. 1985. Tropical Forestry Action Plan. Rome. Available at: www.ciesin.columbia.edu/docs/002-162/002-162.html

International Model Forest Network. 2005. Model forest list. Ottawa, Canada, International Development Research Centre (IDRC). Available at: www.idrc.ca/en/ev-41778-201-1-DO_TOPIC.html

Kaimowitz, D., Mertens, B., Wunder S. & Pacheco, P. 2004. Hamburger connection fuels Amazon destruction: cattle ranching and deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon. Bogor, Indonesia, Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Available at: www.cifor.cgiar.org/publications/pdf_files/media/Amazon.pdf

Koné, P., Durst, P., Prins, C., Marx Carneiro, C., Abdel Nour, H. & Kneeland, D. 2004. In the beginning, there were six Regional Forestry Commissions. Unasylva, 218: 10–17. Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5841e/y5841e04.htm

Muthoo, M.K. 1995. International development cooperation in Forestry. Unasylva, 182: 54–60. Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/v6585e/v6585e09.htm

Smith, N.J.H., Serrão, E.A.S., Alvim, P.T. & Falesi, I.C. 1995. Amazonia – resiliency and dynamism of the land and its people. Tokyo, Japan, United Nations University Press. Available at: www.unu.edu/unupress/unupbooks/80906e/80906E00.htm#Contents

United Nations. 1992. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Annex III, Non-Legally Binding Authoritative Statement of Principles for a Global Consensus on the Management, Conservation and Sustainable Development of All Types of Forests. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992. A/CONF.151/26 (Vol. III). New York. Available at: www.un.org/documents/ga/conf151/aconf15126-3annex3.htm