| SOCIO-ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF VILLAGE CHICKEN PRODUCTION IN AFRICA : THE ROLE OF WOMEN, CHILDREN AND NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS |

| Aichi J Kitalyi | |

| Andre Mayer Research Fellow, FAO Animal Production and Health Division, P.O. Box 315, MPWA-PWA, Tanzania |

The paper stresses the need for a new research thrust on village chicken keeping. Past research has not explicitly included user differentiation and participation in the technology development process. Many developed production technologies including specialised breeds and intensive management systems are not compatible with the socio-economic circumstances in the village chicken production system. Ownership pattern, control and access of resources and distribution of benefits are issues, which are not adequately addressed. Village chicken production systems contribute over 80% of the poultry products in most countries in Africa. Most literature indicates that disease, and specifically Newcastle disease, is the major constraint in the production system. However, there is no clear understanding of the relationships of diseases and other production aspects. Laboratory and on-station research results on control of diseases are promising. However, on-farm testing and continuous impact assessment are required in order to introduce technologies compatible with socio-economic circumstances in the rural sector. Most literature reports that subsistence village chicken production in Africa is in the domain of women and children. However, the local knowledge, role and perceptions of the target groups are not adequately incorporated in the technology development process. This situation calls for gender-aware programmes to improve the African village chicken production system.

INTRODUCTION

Africa has fifty-two independent countries. These countries are at different stages of socio-economic development measured in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as well as Human Development Index (HDI). According to Instituto del Tercer Mundo (1992) the HDI is a better indicator of human welfare than the GDP. Nevertheless Map 1 (a) and (b) shows that most of the countries with HDI less than 0.5 also have low GDP. These countries are average egg producers. According to Quresh (1992) the African countries can be put in four categories on the basis of rate of increase in egg production between 1960 and 1990 shown in Map 1 (c). Incidentally, the average producers are the countries dominated by rural poultry production.

|  |

| Map 1. African countries developement stages: HDI (a), GDP (b) and egg production. |

Maps 1a, 1b and 1c

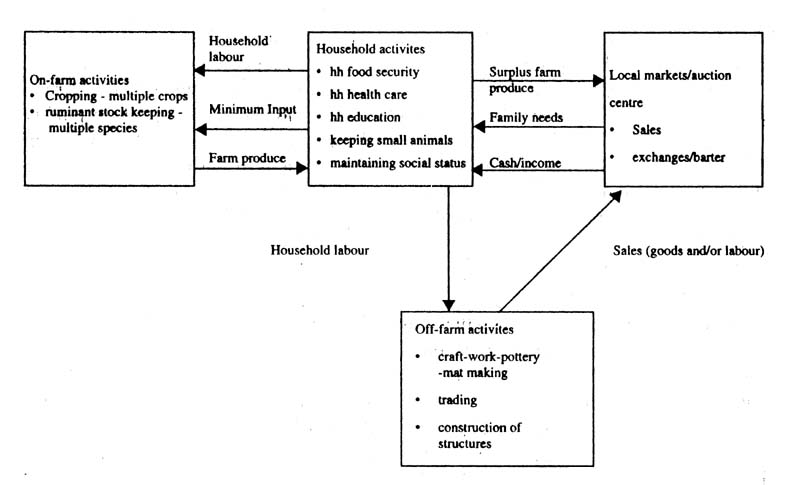

Figure 1. Rural farming system in Africa: main components of a household in a mixed farming system

Rural poultry have been described by various workers (Sonaiya, 1990; Martin, 1992 and Spradbrow, 1993). Common terms in all these descriptions are; free range, scavenging and scratcher chicken, which imply low-input production systems. In some definitions, it is stated that the chickens are of indigenous type (Spradbrow, 1993), while Sonaiya (1990) includes any genetic stock, unimproved or improved. Another aspect considered in these descriptions is the flock size, which is small, with the upper limit suggested to be 100 (Martin, 1992). Other definitions included economics aspects showing that the production system is a low-input low-output system. The intensive commercial poultry production enterprises found in rural Africa are not included in these descriptions. Village chicken production system in the context of this paper is the village chicken keeping where the chickens form part of the whole farming system and are closely interrelated with the other components of the farming system. The subsistence farming system is complex (Figure 1) and inclusion of the socio-economic aspects in the definition of village chicken production system, will bring additional dimensions.

Another commonly reported feature of African village chicken systems is the management which is mainly the domain of women. To support this school of thought, one would need to have an understanding of the socio-economic importance of rural poultry in Africa. Key issues in understanding the socio-economic aspects of poultry include; ownership, labour profile, control and access of resources and distribution of benefits in the production system. The succeeding sections of this paper will look into the socio-economic aspects of rural poultry production in Africa, on the basis of secondary information and the author's field experience in Tanzania.

OWNERSHIP PATTERN

There is dearth of information on the ownership pattern of village chicken production systems. In a series of country reports on smallholder rural poultry production in Africa, no country gave a clear picture of the ownership pattern (CTA, 1990). In a number of situations it was mentioned that women and children take care of the chickens. Kuit et al., (1986) discussing ownership of poultry in Mali said, “Although ownership of poultry resides with the head of the household, women and even children are the chief decision makers from day to day”. On the other hand, Williams (1990) describing the traditional poultry keeping system in Ghana, refers to the owner of the chickens who has to move the chicken from homestead to fields as ‘he’. In a recent workshop on village chickens in Pretoria, group discussions on the ownership of village chickens revealed that there are within-country variations. In Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, three patterns were described; family ownership, women and men ownership and individual ownership, depending on the mode of acquisition of the chicken (purchase, inherit or gift). Therefore general statements on ownership may be misleading.

The ownership of village chickens in most African societies is a product of social and cultural aspects of society. For example in one of the societies in Tanzania where village chickens are owned by men, it was reported that in the past it was a taboo for women to eat poultry products. Based on this taboo or stereotype, chickens in this society are owned by male members of the family only. In other societies, mainly in the pastoral communities, men are not associated with poultry because they are responsible for ruminant stock. In the coastal areas of Tanzania where there is no tradition of keeping large stock both male and female farmers own chickens (field observations).

Understanding the relationship between ownership of resources and labour profile, control and access of resources as well as the distribution of benefits accrued, is a pre-requisite to successful interventions in the village chicken production system.

LABOUR PROFILE

Discussion on the overall labour profile for rural women is beyond the scope of this paper. Suffice it to say, most women in rural Africa are over-burdened with various activities, exacerbated by the poor social infrastructure. Activities in the traditional village chicken keeping are; cleaning, attending the brooding hens and chicks in the first few days of life and supplementary feeding of grains, particularly when the chickens are confined. These activities are in the sphere of the household and are carried out by women and children. Involvement in the marketing of the products varies from one community to another, depending on ownership pattern, distance to markets and the person in charge of decision making for product sale. There are cases where women cannot participate in marketing, if it will involve going some distance from the homestead.

In introducing poultry improvement technologies that require labour input, it is important to know the opportunity cost of labour for the different household members and for different seasons. This has to be calculated with an appreciation of the gender specific activities found in all human cultures. There is scanty information on labour input from women and children and its effect on village chicken production systems. In a small data base on rural poultry production in Africa with over 200 entries none of the studies did a critical analysis of the labour input let alone gender desegregated data.

It could be interesting to relate the various village chicken production constraints with the labour opportunity cost of the different gender categories. For example, where women are responsible for caring of the chicks, chick mortality could be related to available labour input from women. Similarly, activities such as disease control, construction of shelters and marketing will be affected if they are not priority areas for say, men who might be socially responsible. Disease control in village chickens is an area, which depends greatly on the extension/advisory services. For successful village chicken interventions, the extension/advisory services should be able to target the potential information users. This may be a problem in African countries which already have problems in maintaining an efficient agricultural extension system, are targeting poultry extension efforts in commercial poultry production system, and make little effort to understand village chicken or the intra-household dynamics including gender roles.

DISTRIBUTION OF BENEFITS

Reports on functions of village chickens have shown similarities across the African countries (Williams, 1990; Kaiser, 1988; Bourzat and Saunders, 1988; Yami, 1995;

Table 1. Production parameters of village chicken production systems in Africa reported in literature

| Reference | Country | Clutches/year | Eggs/clutch | Egg weight (g) | Hatchability | Mature weight | Mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g) | (%) | (kg) | (%) | ||||||

| Cocks | Hens | ||||||||

| Shanawany and Banerjee (1991) | Ethiopia | - | - | 44–49 | 39–42 | 1.1–1.7 | 1.0–1.2 | - | - |

| Bourzat and Saunders (1989) | Bukina Faso | 2.7–3.0 | 12–18 | 30–40 | 60–90 | - | - | 83 | 98 |

| Minga, et al (1989) | Tanzania | - | 6–20 | 41 | 50–100 | 1.2 | 2.2 | <80 | - |

| Veluw (1987) | Ghana | 2.5 | 10 | - | 72 | - | - | 50 | 50 |

| Wilson et al. (1987) | Mali | 2.1 | 8.8 | 34.4 | 69.1 | 1.6 | 1.02 | 56 | - |

| Wilson (1979) | Sudan | 4.5 | 10.87 | 40.6 | 90 | 2.1 | 1.31 | - | - |

Diambra, 1990). The main functions of rural poultry are; home consumption (meat and eggs), social obligations and sales or in exchange for goods and services. In Niger, home consumption and ceremonies account for 35%, gifts 20%, sales or barter 45% (Kaiser, 1988). In Ghana chickens play a special leading role in cementing marriages, friendships and even resolving quarrels and enmity between neighbours, lovers, brothers and comrades (Williams, 1990). Referring to a specific traditional society of the Manprusi in Ghana, Veluw (1987) report the functions of poultry as; 35% sacrifice, 28% sale, 15% consumption, 13% gift and 10% breeding stock. In the case of Ghana, 71% of the eggs are kept for hatching, 18% for sale, 5% for gifts and 5% for consumption.

Importance of cash economy is rapidly diffusing into even the remotest areas of developing countries. Village chickens have been identified as one of the sources of income and particularly to the households which do not have access to land or other important resources such as cattle. Village chicken production in Niger has been reported to produce higher income than minimum labour wage (Kaiser, 1990). In Ghana village chickens are estimated to contribute over 15% of the household cash income (Veluw, 1987). Village chicken production systems in Africa have been ridiculed because of the low production potential (Table 1). It can be argued that the high mortality rate is the major cause of low production levels because this result in a low annual yield of about two chicken per hen (Veluw, 1987; Bessei, 1993). However, comparative data for the other parameters might not be rational because they are not backed up with costs and benefit analysis. Some schools of thought consider production efficiency of the village chicken production system is high because of the low inputs involved. Another key issue for consideration is the validity of poultry production data reported in literature. Most of the data found in literature is based on estimates by responsible professionals. Where field surveys have been conducted there are limitations especially where the data depend on the memory recall of farmers who normally do not keep records.

There is dearth of information on the village chicken marketing system as well as distribution of benefits accrued from village chickens in Africa. In the data base of over 200 entries reviewed none has looked into these aspects. However, access to products and benefits of the production system is crucial for the successful adoption of improvement technologies. How the outputs (economic and social) of village chickens are shared in a household depends on the socio-economic behaviour of the household. Although women and children have key roles in decision making in village chicken production, distribution of the benefits is not so clear. In the preceding section there was mention of the taboos in some societies where women can not eat some chicken products (for example eggs). In Ghana where cocks are used for sacrifices, the blood is for ancestors, and the meat is eaten by male household members. Negative response to poultry improvement projects from women was reported in Sudan, where the women had no access to the income accrued from poultry. It is therefore imperative to understand gender relations, and their influence on household economic behaviour in poultry projects aiming at improving the welfare of women. The high variation in socio-economic circumstances within and between countries will require case by case analysis.

WOMEN, CHILDREN AND NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS IN VILLAGE CHICKEN PRODUCTION

Literature on African traditional village chicken production systems mentions women and children as the main keepers of chickens. Poultry production is dominated by women even where intensification has been introduced. This situation is supported by Bradley (1992) in a review of historical relationships between women and poultry development. He explained the closer association of poultry and women because there are livestock kept in the sphere of the household. In response to this paradigm, poultry keeping has ranked high among small enterprises suggested for improving the economic status of women in rural Africa. Where these introductions have been guided by government policies, the target groups are not reached. A major constraint in achieving the objectives of such projects is the prevailing inferior socio-economic role of women in the African rural society. It is therefore important to understand the interrelationship between the status of women and economic and social services available in rural areas.

The role of non governmental organisations (NGOs) in village chicken keeping can be discussed in view of the NGOs role in poverty alleviation. Advancements in women in development programmes have resulted in the formation of a number of NGOs, which emphatically support gender-aware anti-poverty programmes. NGOs are better placed than government institutions for the inclusion of gender in their programmes, because of their innovative nature and flexibility compared with the more rule-bound culture of most bureaucracies (Kabeer, 1995).

The preceding discussion on the socio-economic aspects of village chicken production shows that in some situations there are social constraints which prevent women having access to a fair share of resources and benefits of the production system. NGOs following process-based approach to policy design, can best address this problem in rural poultry development projects. Transformation of the village poultry production system from subsistence to income-generating activity will require organisational building, particularly for input supply systems and marketing. This is an area where again NGOs have advantages over the bureaucratically managed planning institutions.

There are examples of NGOs in the Asian continent, which have successfully organised farmer groups and associations in poverty alleviation programmes, such as; Grameen Bank of Bangladesh and the Self-employed Women's Association of India. The success of NGOs in Africa is yet to be assessed. Needless to say the differences in culture within and between societies warrant case by case analysis of the prevailing situation.

FUTURE PROSPECTS

Review of literature on village chicken production systems in Africa show that scientists, development agents and policy makers do not have clear understanding of either village production system or the socio-economic aspects in village chicken keeping. Further, the validity of the data given in literature is questionable because of the weaknesses associated with the data collection methods. There is need to review the available data collection techniques in use and examine alternatives. The recent developments in participatory techniques as tools for data and information collection in rural areas can be employed to improve data collection in village chicken production systems.

The socio-economic structure of village chicken production systems calls for gender-aware interventions. Although village chickens are predominantly the domain of women, interventions directed at women must be introduced cautiously. NGOs have a key role to play in capacity building and organisational aspects to address the disadvantaged groups. However, in view of scarce resources, networking for co-ordination purposes is necessary. Networks should involve the producers, in order to address producer needs. As indicated above the village chicken production system is a component of the whole farming system. There is need to understand the various factors affecting the production system at household level, village level and external factors from urban or national level. Long term efforts are required to achieve this.

The future of the village chicken production system in Africa is promising because donor agencies such as United Nations as well as NGO's have realised that addressing this sector will target the poorest and the most disadvantaged groups in developing countries.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation of United Nations is supporting a research programme in Africa to investigate ways of stimulating evolution of the village chicken production system into a more productive market oriented system. An in-depth review of literature will be carried out in collaboration with institutions which support rural poultry production in the tropics. Field studies will be conducted in four African countries namely; Ethiopia, Gambia, Tanzania and Zimbabwe with a critique review of the data collection methods used in poultry development projects. Alternative methods including use of participatory tools will be tested in Zimbabwe and Tanzania. The village chicken production system will be studied at five different levels; flock level, household level, inter-household level, village level, inter-village level to identify the relationships and their effects on flock management and disease epidemiology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am grateful to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of United Nations for sponsoring me to this congress. My sincere thanks to Dr. Andrew James and Mr. Jonathan Rushton of Reading University, UK, for their comments on the first draft. Remarks and comments from Drs. Kris Wojciechowski, Rene Branckaert and Mark Rweyemamu of FAO, Rome are highly acknowledged.

REFERENCES

BESSEI, W. (1993) Lessons from field experience in the development of poultry production. In: MACK, S. (ed). Strategies for sustainable animal agriculture in developing countries. Proc. FAO Expert Consultation, Rome Italy.

BOURZAT, D. and SAUNDERS, M. (1990) Improvement of traditional methods of poultry production in Bukina Faso. In rural Poultry Production in Hot climates, 12 June 1987 Hamelin, Germany

BRADLEY, F.A. (1992) A historical review of women's contribution to poultry production and the implication for poultry development policy. In proceedings of the XIX World Poultry Congress, Amsterdam the Netherlands 20–24 September 1992. 693–696

CTA. (1990) Smallholder rural poultry production. International seminar, 9–13 October 1990. Thessaloniki. vol 1.

DIAMBRA, O.H. (1990) State of smallholder rural poultry production in Cote D'Ivore. In: CTA Seminar Proceedings, Smallholder Rural Poultry Production, 9–13 October 1990, Thessaloniki Greece. p. 107 – 116

INSTITUTO DEL TERCER MUNDO (1992) Third World guide 1993/94. a view from South. Instituto del Tercer Mundo, Uruguay p 67 – 72

KABEER, N. (1995) Targeting women or transforming institutions. Policy lessons from NGO anti-poverty efforts. Development in Practice, Volume 5 (2) 109 – 116

KAISER, D. (1990) Improvement of traditional poultry keeping in Niger. In rural Poultry Production in Hot climates, 12 June 1987 Hamelin, Germany

KUIT, H.G., TRAORE, A. and WILSON, R.T. (1896) Livestock production in Central Mali: Ownership, Management and Productivity of Poultry in the traditional sector. Tropical animal health production 18: 222 – 231

MARTIN, P.A.J. (1992) The Epidemiology of Newcastle disease in village chickens. In Newcastle disease in village chickens, control with thermostable oral vaccine (Ed. Spradbrow, P.B.) Proceedings, International workshop held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 6–10 October 1991. Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), Canberra (1992) pp. 40–45

MINGA, U.M., KATULE, A., MAEDA, T. AND MUSASA, J. (1989) Potential and problems of the traditional chickens industry in Tanzania. Proceedings of the 7th Tanzania Veterinary Association Scientific Conference pp. 207 – 215

QURESH, A.A. (1992) Growth in population keeps per capita egg consumption low. Africa in four decades Misset-World-Poultry 8: (4) p 45–46.

SHANAWANY, M.M. AND BANERJEE, A.K. (1991) Indigenous chicken genotype of Ethiopia. (unpublished)

SONAIYA, E.B. (1990) Towards sustainable poultry production in Africa. FAO Expert consultation on strategies for sustainable animal agriculture in developing countries. Rome, Italy

SPRADBROW, P.B. (1993) Newcastle disease in village chickens. Poultry Science Review 5: 57–96

VELUW, K.van (1987) Traditional poultry keeping in Ghana. ILEIA-December 1987. 3: (4) 12 – 13

WILLIAMS, G.E.S. (1990) Small holder poultry production in Ghana. In: CTA Seminar Proceedings, Smallholder Rural Poultry Production, 9–13 October 1990, Thessaloniki Greece. p. 89 – 97

WILSON, R.T. (1979) Studies on the livestock of Southern Darfur Sudan. VII. Production of poultry under simulated traditional conditions. Tropical Animal Health production 11: 143–150

WILSON, R.T., TRAORE, A., TRAORE, A., KUIT, H.G. and SLINGERLAND, M. (1987) Livestock production in Central Mali: Reproduction, growth and mortality of domestic fowl under traditional management. Tropical Animal health production 19: 229–236.

YAMI, A. (1995) Poultry Production in Ethiopia. World's Poultry Science Journal Vol. 51, July 1995. p 197 – 200