Improving nutrition of many millions who suffer from hunger and malnutrition and to others who are at risk of malnutrition in future, is a matter of prime concern to planners, policy makers and nutrition related professionals. Many goals have been set to improve nutrition in the recent past with commitments made by government and international initiatives and efforts. The International Conference on Nutrition (ICN) and the World Food Summit (WFS), held respectively in 1992 and 1996, remind us that the most basic of human rights is the right to enough food to support a healthy life.

Realisation of this basic right to food security requires access by all people at all times to the food needed for a healthy life' (FAO/WHO 1992). Food is accessed by home production, the gathering of wild foods, purchase with cash or exchange in kind and as gifts of food and food aid. Realisation of this basic right to food flows from strategies and measures ensuring the availability of sufficient food and access to food by those who do not produce it.

Ensuring varied food intakes, containing all essential macro- and micro- nutrients (vitamins and minerals) in sufficient quantities, through a balanced and diversified diet is also essential to support an active, healthy life. If a person is ill, these food requirements will need to be modified. Food also needs to be safe, and free from dangerous contamination. It must not contain high levels of natural toxins, such as aflatoxins, or artificial toxins such as pesticides. Families need to obtain and prepare enough food without alteration of its nutritive value and without contamination from dangerous substances.

Nutritional security thus involves the consumption and physiological use of adequate quantities of safe and nutritious food by every member of the household to support an active, productive and healthy life. For this to be achieved, households need adequate access to enough food to satisfy the nutritional needs of every member. Food then needs to be equitably distributed within the household, and each member needs to be in a state of good health, without the presence of any illness. Nutritional security thus envisages nutritional well being for all people, whereby sufficient quantities of safe and nutritious food are equitably distributed within households and among all communities and nations.

There is need to explore the full meaning of these twin pillars of food security and nutrition security both together and as separate terms, as they are linked in an interactive way. Not only are these linkages important features of effective policies and plans, they are essential features for the design and implementation of effective interventions.

Achieving food security requires considering all the things households do to earn money and survive. It also entails effective responses to the constraints on these activities. For example, purchases often account for a significant portion of total food consumption by families, especially in poorer households and communities, and the sale of surplus production by farm households is often an important source of income. Thus, markets may be a constraint, and change in access to markets or in prices influence food security.

What happens to the food after it is acquired, in terms of storage, preparation and safety is also important. Food and nutritional insecurities result if there is not enough fuel to prepare the food, if there is the storage facilities are insufficient or unsafe, if sanitation hinders food hygiene during food processing, preparation and consumption.

Access by households to sufficient quantities of food does not mean that all members of the family are acquiring food in the necessary quantities and nutritional qualities to support an active, healthy life. This food thus needs to be distributed within families and households to meet all the nutritional needs of each of its members. Even this does not ensure that each member actually eats enough food or the nutritious food.

Undernourished people cannot be as productive as when they are well nourished, and their potential and capacities cannot be optimally tapped when people are in a state of poor nutrition. These significant consequences of nutritional insecurity merit attention in developing Asian countries along consideration of the following important consequences:

In infants and young children, undernutrition and growth retardation are associated with impaired intellectual development, lowered resistance to infection and increased rates of illness and death.

Vitamin A deficiency leads to lower immunity and increased death rates in children, night blindness, and it is also the most important cause of preventable childhood blindness.

In women, poor nutritional status is associated with increased prevalence of anaemia and of giving birth to low birth weight babies with higher incidence of death, disease and illness.

In adults in general, undernutrition, anaemia and iodine deficiency can lead to poor health, resulting in impaired physical and intellectual performance, and lower productivity.

In the long term, lower productivity due to malnutrition constrains the potential of communities and countries to achieve sustainable development.

This publication explores Asia's potential for achieving nutritional security in the new century and beyond. This section proceeds to furnish a regional overview in global perspective of some major trends. While its focus is undernutrition, it also takes note of growing concerns about overnutrition. It introduces the Dietary Energy Supply as the measure of available food for direct human consumption followed by a look at population growth as influencing food availability and, in turn, the prospects for nutritional security. It highlights the commitments made by governments at world conferences, wherein they shared their reviews of the national situation and their evaluation of successful interventions to furnish a reliable basis for their consensus identification of a set of recommendations. The discussion then follows the evolution of international standards adopted by governments to enhance their efforts in effective design and implemention of plans, policies and programmes to meet these commitments.

The Dietary Energy Supply (DES) is a widely used indicator of aggregate food and nutrition situations and it is expressed as an estimate of the average daily energy available for human consumption in the total food supply during a given period. The average per person food supplies available for direct human consumption in developing countries increased in the 1980s, although at a slower rate than in the 1970s, as shown in Table 1 below. Even though these supplies decreased in several countries during the 1980s, by the end of the decade about 60 percent of the world's population were living in countries with an excess availability of 2 600 kcal per person per day. Low Income Food Deficit countries (LIFDCs) experienced small but steady increases, but the food supply in Least Developed countries (LDCs) remains unchanged, at 2040 kcal.

Table 1. DES (Calories per Day per Person) by Region and Economic Group

| Region and economic group | 1969–1971 | 1979–1981 | 1990–1992 |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 2 440 | 2 580 | 2 720 |

| Developed countries | 3 190 | 3 280 | 3 350 |

| Developing countries | 2 140 | 2 330 | 2 520 |

| East and South East Asia | 2 060 | 2 370 | 2 680 |

| South Asia | 2 060 | 2 070 | 2 290 |

| Least developed countries (LDCs) | 2 060 | 2 040 | 2 040 |

| Low income food deficit countries (LIFDCs) | 2060 | 2230 | 2450 |

Source: The Sixth World Food Survey (FAO 1996a)

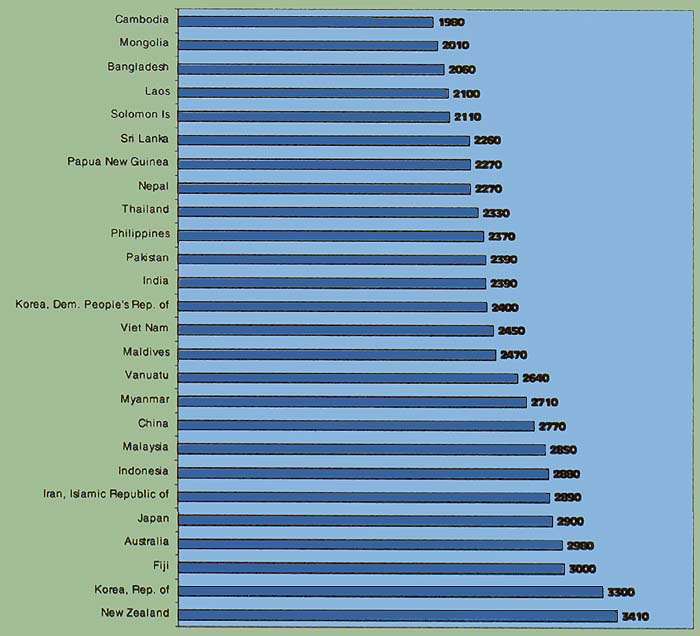

Grouping countries above and below a daily supply of 2 600 kcal/person further highlights disparities; whereby, in 1989–1990, 41 developing countries (with populations over 1 million) had food supplies above 2 600 kcal/person, and 15 countries had supplies above 3000 Calories. In contrast, only three developed countries had less than 3 000 kcal available (FAO/WHO 1992). The most recent data for 1994–1996 shown in Figure 1 below, highlights disparities within Asia and the Pacific region, whereby a majority of 15 countries had an available food supply of below 2600 kcal/day/person, and only three countries had supplies of 3 000 kcal or above.

Figure 1. Dietary Energy Supply (DES) in Asia and Pacific Countries, 1994–1996 (Calories/day/person)

Source: FAOSTAT, Rome, 1999.

Chronic Energy Deficiency (CED) furnishes an important measure of basic energy requirements of an active and healthy life for which sufficient food must be available. FAO data highlights the availability of enough food in the world, if distributed according to individual requirements, to provide well over what would have been needed to meet these energy needs. The dietary energy supplied by the available food supplies increased in developing countries during the two decades spanning the period between 1969–1971 and 1990–1992 (FAO 1996a). As a result, the prevalence of food inadequacy fell from 35 per cent to 20 per cent, representing a decline from one in three persons to one in five.

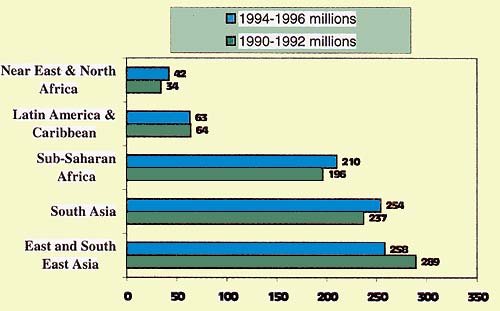

Despite these improvements, in 1994–1996 an estimated 828 million people in developing countries regularly failed to have access to enough food to meet their dietary energy needs for an active, healthy life (SWFS 1998, FAO Home Page). This represents an increase from 822 million people in 1990–1992. Declines took place in East and South East Asia, but an additional 17 million South Asians became undernourished during this period, as shown in Figure 2 below. Not only is the number of chronically undernourished people rising in the world, but nearly two-thirds of these energy deficient people lived in Asia — 512 million - in 1994–1996.

Figure 2. Number of Undernourished People

FAO HomePage, 1999.

The Asian and Pacific region experienced continued improvement in alleviating chronic energy deficiency during the last 20 years, with the proportion of the population affected falling from 41 to 16 per cent in East and South East Asia and from 33 to 22 per cent in South Asia (FAO 1996a). Total numbers declined in East and South East Asia from 289 million to 258 million people, but South Asia experienced an increase from 237 million to 254 million. Children form the largest vulnerable group experiencing energy deficiency, and most of these undernourished children live in Asian countries.

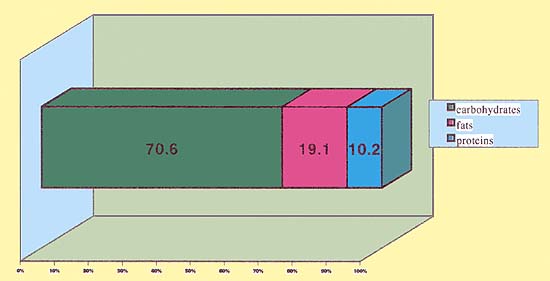

To support an active and healthy life, dietary energy must come from diverse food sources. Protein supplies in South Asia remained constant during the 1980s, but increased in the 1980s. In East and South East Asia increases characterize the last two decades. Data for 1994–1996 in Figure 3 illustrate that the available food supply in Asia and the Pacific remains deficient in sources of protein and fat relative to carbohydrate. The average fat and protein intakes need to be increased, which presently amount to about 19 percent and 10 percent, respectively. This lack of food diversification gives rise to protein energy malnutrition (PEM), which is widespread throughout the world. Children are the major victims of PEM, an estimated 192 million children under age 5 years suffer from acute or chronic symptoms.

Source: FAOSTAT, Rome, 1999

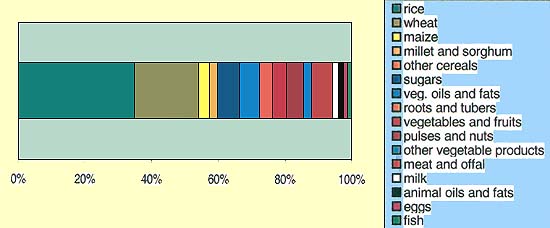

Worldwide, the most prevalent micronutrient deficiencies are lack of iron, iodine and vitamin A (FAO 1996a). More than 2000 million people in the world experience the consequences of iron deficiencies, 1 000 million are at risk to iodine deficiency, and 40 million consume insufficient vitamin A. Over 50 per cent of the population in developing countries, and in Asia in particular, are affected by these deficiencies. Large numbers also suffer the consequences of other micronutrient deficiencies, such as those caused by a lack of B-complex vitamins, zinc, selenium and other trace elements. Availability and accessibility to food diversification and variety is essential for overcoming micronutrient deficiencies. However, as the data in Figure 4 below illustrates, the major component of the regional food supply is cereals, with inadequate food diversity in essential sources of micronutrients, such as vegetables and fruits, roots and tubers, and pulses and nuts.

Source: FAOSTAT, Rome, 1999

Simultaneously throughout Asia, diet-related non-communicable diseases, such as obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and some forms of cancer, are emerging as public health problems. Available data in South East Asia indicate that many Asian countries are undergoing a “nutrition transition” that is associated with major increases in obesity prevalence arising from a combination of shifts in diet structure, overconsumption and reduced physical activity (Popkin 1994). This transition coincides with the rapid process of urbanisation and rising incomes in urban centres in many Asian countries.

Considering the multifaceted character of food and nutrition security, it is imperative for Asian governments to undertake concerted national action and that these actions be both strengthened and supplemented by international efforts in the region. In keeping with their commitments at two world conferences, the International Conference on Nutrition (ICN) in 1992 and the more recent World Food Summit (WFS) in 1996, Asian governments assumed responsibility for undertaking the following actions:

In keeping with these commitments, it becomes essential to translate them into effective intervention. Designing effective strategies and measures to enhance Asian prospects beyond 2000 flows from an elaboration of the current situation. It needs to examine the food and nutrition security situation of Asian countries and then furnish an elaboration on comprehensive policy frameworks leading to programme and project intervention. These activities need to take account of socio-economic priorities and concerns and identify appropriate responses to the socio-cultural diversity in Asian countries. This combination of activities not only supports the design of effective initiatives and interventions, it also serves as the catalyst for further and sustained actions by Asian governments. Therefore, after exploring the linkages between the twin pillars of food security and nutritional security (Section II), this publication then probes major indicators of Asia's nutrition scenario as current trends and prospects beyond 2000 (Section III). This scenario is supplemented by national trends in South Asian and South East Asian countries (Appendices VIII.A and B). The nutritional transition underway in Asian countries is taken into account (Section IV), followed by identification of components for a policy framework to design national strategies and measures as support for policy, programme and project intervention (Section V). An exposition of interventions by Asian countries supplements the presentation (Appendices VIII.C and D). Substantive discussions also examine strategies and measures for achieving nutritional security in emergency situations and during the present economic crisis underway in many Asian countries. Enhancing Asian prospects is the final focus of the publication (Section VI). The forthcoming discussion examines the evolution of international standards for ensuring safe and nutritious food for every person, household, community and nation.

The expansion in international trade in food has increased the risk from cross-border transmission of infectious agents and underscores the need to use international risk assessment to estimate the risk that microbial pathogens pose to human health. The globalization and liberalization of world food trade, while offering many benefits and opportunities, also presents new risks. Ensuring safe food that will not cause harm to the consumer, thus, requires enhanced levels of inter-governmental co-operation in setting international standards. This co-operation is featured in a wide range of undertakings, codes, standards, guidelines, recommendations and conventions adopted by member states of the FAO at its Council/Conference following formulation and negotiation through its Commissions.

The most important instruments evolve from the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) as the implementation agency for the Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme. It was established as an inter-governmental statutory body of FAO and WHO in 1962, with 165 member states at present (see Table 2 below for members in Asia and Pacific region). Codex Alimentarius (a Latin term for food law or food code) brings together scientists, technical experts, governments, consumers, and industry representatives to develop international standards for food production, processing and trade. It is supported by expert committees working on a range of topics; namely, food additives and contaminants, residues of veterinary drug in foods, pesticide residues, food hygiene, general principles, food labeling, food import and export inspection and certification systems, nutrition and foods for special dietary uses, methods of analysis and sampling and meat hygiene.

| Table 2. Member States of the Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations in Asia and the Pacific (FAO, RAP) and of the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) and the World Trade Organization (WTO), June 1999 | ||

| FAO member states | Codex CAC members | WTO members, or Date applied* |

| Australia | yes | yes |

| Bangladesh | yes | yes |

| Bhutan | yes | NO |

| Cambodia | yes | NO December 1994 |

| China | yes | NO March 1987 |

| Cook Islands | yes | NO |

| Dem. P.R. of Korea | yes | NO |

| Fiji | yes | yes |

| India | yes | yes |

| Indonesia | yes | yes |

| Iran | yes | NO |

| Japan | yes | yes |

| Kazakhstan | NO | NO February 1996 |

| Korea, Republic of | yes | yes |

| Lao People's Dem. Rep. | yes | NO February 1998 |

| Malaysia | yes | yes |

| Maldives | NO | yes |

| Mongolia | yes | NO |

| Myanmar | yes | yes |

| Nepal | yes | NO June 1987 |

| New Zealand | yes | yes |

| Pakistan | yes | yes |

| Papua New Guinea | yes | yes |

| Philippines | yes | yes |

| Samoa | yes | yes |

| Solomon Islands | yes | yes |

| Sri Lanka | yes | yes |

| Thailand | yes | yes |

| Tonga | yes | yes |

| Vanuatu | yes | NO July 1995 |

| Viet Nam | yes | NO January 1995 |

| Source: FAO and WTO Home Pages, April 1999; | ||

| Note:* = WTO Working Party established for accession. | ||

The Codex Standards are designed to meet two objectives; namely, ensuring consumers health, and supporting fair practices in the food trade, albeit domestic exchange or export. Since its formation in 1962, the range of Standards developed by the CAC covers all foods, whether processed, semi-processed or raw, intended for sale to the consumer or for intermediate processing. Over 200 Standards, 45 Codes of Practice and 2000 Maximum Limits for residue of agricultural and veterinary chemicals have been established.

The growing significance of the Codex Alimentarius Commission is attributed to two agreements arising from the Uruguay Round of Multilateral Trade Negotiations, which has established a new World Trade Organization (WTO). These agreements now furnish provisions governing the export of safe food and food products for the 134 member states of WTO, see Table 2 above. Negotiations on reducing non-tariff barriers to international trade in agricultural products flow from Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, known as the SPS Agreement, and Technical Barriers to Trade, known as the TBT Agreement.

The SPS agreement requires WTO members to conduct science-based risk assessments, in setting limits for health risks in foods. It applies to all measures that countries put in place to protect their human, animal and plant life or health, and which may directly or indirectly affect international trade. Essentially, SPS measures are food safety and animal and plant quarantine measures. The SPS contains specific references to the standards, guidelines and recommendations established by the Codex Commission relating to food additives, residues of veterinary drugs and pesticides, contaminants, methods of sampling and analysis, and codes and guidelines of hygienic practice.

The TBT Agreement was developed to prevent the use of national or regional technical requirements, or standards in general, as unjustified technical barriers to trade. Since TBT covers all types of standards, the agreement extends coverage to all aspects of food standards other than those related to SPS measures; such as quality provisions, nutritional requirements, labeling and methods of analysis. TBT also contains a very large number of measures designed to protect consumers against deception and fraud.

Codex Standards, thus, serves as a point of reference in international law and increasing demands are being made on it in response to the need for harmonising these international agreements with emphasis to scientific rigour and transparency. Codex standards and guidelines also are responsive to worldwide concerns about increasing food safety and quality of domestic and imported food for achieving nutritional security.

Other FAO activities supplement and support the formulation of international standards for food quality and food safety. For example, the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) has been in existence since 1955 and serves as a scientific advisory committee to FAO, WHO, Member Governments and the Codex Alimentarius Commission. The JECFA assesses the human health risks associated with the consumption of additives to food. Based on these assessments, it recommends Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) levels, tolerable limits for environmental and industrial chemical contaminants in food and Maximum Residue Levels (MRL) of agricultural chemical inputs in food.

Supplementing Codex standards, member states of the FAO have adopted a series of international instruments dealing directly or indirectly with biosafety and biotechnology (FAO/WHO Joint Consultations 1990 and 1996, Lupien 1999). Beginning in 1983, member states of the FAO Conference adopted the International Code of Conduct for Plant Germplasm Collecting and Transfer, formulated by the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (CGRFA). Nearly a decade later, the FAO Council endorsed the Draft Code of Conduct for Biotechnology as it affects the Conservation and Use of Plant Genetic Resources. Formulated by the CGRFA in consultation with 400 experts worldwide in 1991, this code is designed to minimize the negative effects of biotechnology. Shortly thereafter in 1995, the CGRFA considered the Draft Code of Conduct for Plant Biotechnology and undertook negotiations leading to revision of the International Undertaking on Plant Genetic Resources.

Conventions furnish the most powerful international instruments, being an important commitment among member states to implementation of their provisions. Adopted in 1992, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) covers biosafety involving any technological application that uses biological systems, living organisms or derivatives thereof, to make or modify products or processes for specific uses. It also covers tissue cultures, immunological techniques, molecular genetics and recombinant DNA techniques. The FAO Conference adopted the International Undertaking on Plant Genetic Resources in 1983 and, thereafter, 113 member states have adhered to its provisions. Revision of this undertaking in harmony with the convention is being negotiated through CGRFA, among its 158 member states, including Asian countries.