Though geographically small in size, the Maldive Islands are rich in natural resources, particularly marine biodiversity. These resources have historically sustained the country's scattered island communities, providing for their food and livelihood security. Indigenous community-based practices have traditionally conserved the extent of biological diversity over time, enabling the country's resources to be harvested sustainably to meet people's needs. Local knowledge systems and gender roles have been important in this context. Women have developed skills and capacities to manage the interwoven forest, farm and home garden ecosystems, and to successfully integrate these roles with their responsibilities in a range of other productive activities. Men, on the other hand, have perfected techniques and methods to harvest the marine resources of the lagoons, reefs and open seas.

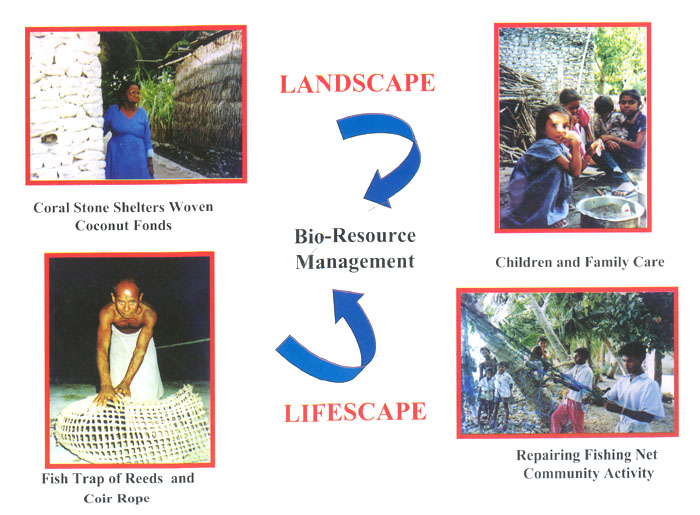

This study is concerned with the biodiversity management of the Maldives. One of its major objectives is to provide an overview of biodiversity management systems in the Maldives, including the traditional systems which have served to conserve the country's natural wealth while, at the same time, enabling island communities to harvest these assets to ensure their own survival. The report explores the natural and human endowments of the Maldives on the basis of the country's landscape and lifescape characteristics. A landscape approach acknowledges the importance of the ecological, social, economic and political environment to community activities and farm life. It also recognises the importance of resource flows through the landscape and external environment. Lifescape, on the other hand, depicts community life and people's use of resources (SANREM CRSP, 1995).

A major component of the document seeks to identify and examine how gender roles have traditionally played a part in the sustainable utilisation and management of natural resources and biodiversity. In this context, it explores the different roles and responsibilities of men and women in harvesting and managing terrestrial and marine-based resources, and their access to these resources. Using this landscape-lifescape approach to analyse and achieve an understanding of gender dimensions is, in many ways, comparable to FAO's “Socio-economic and Gender Analysis” (SEAGA) framework for gender planning. In this case, the socio-economic framework is expanded through the incorporation of a larger bio-resource environmental aspect.

The findings of this analysis enable a number of conclusions and recommendations to be made regarding the optimum direction for natural resource management in the Maldives in the next millennium. Given the rapid rate of population growth and economic development in the Maldives, together with obvious natural threats to the islands' ecosystems, it is hoped that these recommendations will provide guidance to a country already concerned with the need to balance developmental and environmental objectives.

By way of introduction, the following sections focus on the landscape and lifescape of the Maldives. In short, the emphasis is on the scope and makeup of the country's natural, cultural and human capital, as well as its lifescape and governance.

Located in the Indian Ocean, the Republic of Maldives occupies an archipelago of some 1 200 coral islands. The islands are formed into 26 natural atolls lying in a north-south chain, 820 km long and up to 130 km wide (see Map 1). The total area of the country, including land and sea, is about 90 000 sq. km. The lagoons and reef waters of the atolls enclose an area of 21 300 sq. km while the total land area of the islands is less than one percent of the area enclosed by the lagoons. The country's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers more than 90 000 sq. km.

| Formation of Atolls: Atolls are formed in oceanic waters around the base of extinct volcanoes, and are associated with groups or chains of islands. They are formed by the total disappearance of a volcanic mass beneath the sea, and the continued upward growth of coral reefs on this volcanic basement. The result is the formation of a coral atoll, an approximately circular structure or string of islands surrounding a central lagoon. |

The coral atolls of the Maldives are formed upon minor elevations on the Chagos-Lacadive submarine plateau, which ascends from the deep Indian Ocean. This plateau has provided a base for reef building corals, from where they have risen to the surface as illustrated in Figure 1. Most of the atolls have a number of channels or openings in the outer reef which provide access to the islands in the enclosed interior sea or lagoon of the atoll. The shape of the atolls varies from circular and oval, to pear shaped. Some are fairly large such as Huvadhu Atoll in the south, which has approximately 250 islands and a lagoon area covering approximately 2,800 sq. km. Other atolls are very small and contain only a single island, such as Kaashidhoo and Gaafaru in the North Male' Atoll.

Figure 1. Profile of an Atoll and Lagoon

The islands of the atolls are very small, varying in size from 0.5 – 6 sq. km, and include small sand banks as well as larger elongated strip islands. They are generally flat with very few mounds and no rivers; the average elevation is just 1–3 m above high tide level. Some of the larger islands have small fresh-water lakes, some contain swampy depressions, and some have brackish water with mangroves along the edges. The soil on most islands has a poor water-retaining capacity and is highly alkaline due to an excess of calcium from the basal coral rock. Rain water percolates through the highly porous sand and forms a freshwater lens above the sea water (see Figure 2). This fresh water is easily obtained by sinking shallow wells.

The natural resources of the atolls have long been precious to the people of the Maldives. Indeed, for many centuries, Maldivians have survived on their country's marine resources. Natural house reefs surround and protect each of the islands from rough seas. These protective coral reefs are submerged underwater gardens, home to hundreds of species of multicoloured tropical fish, countless shapes and sizes of coral and shells, and various sea grasses. For instance, they shelter 250 species of hermatypic coral, more than 1 200 reef fish, 500 shell varieties, nearly 200 sponge species, over 100 species of marine crustaceans, more than 100 species of echinoderms, some 235 species of marine algae, as well as 5 turtle species.

There are no hills, mountains, rivers or thick jungle in the Maldives. The islands are characterised by tall coconut palms and white sandy beaches. The terrestrial flora includes some 583 plant species, approximately half of which are domesticated or medicinal plants. The islands contain various species of trees used for timber, and are rich in a wide range of trees and plants of food value. These include coconut, bread fruit, banana, mango, screw pine, cassava, sweet potato, taros and millet.

With the exception of several varieties of sea and shore birds, the island's fauna is rather limited. In general, fauna on the islands comprises lizard species, small mammals like tree shrews, fruit bats and rats, and some 130 insect species such as scorpions, centipedes, rhinoceros beetle and paper wasps. In the homestead the domesticated animals reared are goats and chickens.

Figure 2. The Fresh Water Lens

Evidence suggests that the Maldives has been populated and thriving since as early as the fourth century BC. Recent excavations have uncovered structures related to the ancient Indus civilisation, and it is suspected that this culture thrived between 2 000 - 1 500 BC. There is also evidence of Buddhism, reflecting Sri Lanka's significant influence. It is argued that the earliest settlers migrated from Arabia, eastern Africa and the Indian subcontinent, among other places. Arab merchants arrived in the ninth century, initiating large-scale trading for coconuts, dried fish and, in particular, money cowry. This also resulted in a gradual transition towards Islam and the rule of Sultans. From the sixteenth century onwards, the islands were influenced by Portuguese and Dutch traders. Yet except for 15 years of Portuguese occupation in the sixteenth century, the Maldives has been an independent state throughout its known history. A British protectorate from 1887–1965, the Maldives became a republic in 1968.

The original population of the Maldive Islands is believed to be Dravidian and is presumed to have come under the influence of successive waves of immigration, including a large influx of Aryans in the third century BC, and a strong Arab and slight African influence from the tenth century onwards. These trends are reflected in the language, Dhivehi1. While exhibiting a strong Sinhalese influence, Dhivehi also includes words from the geographical regions of immigrant communities. The local medicinal techniques reflect traditional Chakra, Ayurveda and Unani medical practices.

Gender Roles

Due to their small population and widely dispersed islands, the Maldivians have

developed a socio-cultural pattern characterised by close-knit homogenous communities.

Frequent divorces and remarriages have enlarged the family and diluted its influence on

children. Traditions favouring segregation of women, common in many Islamic countries,

are conspicuously absent in the Maldives. There is free mixing between the sexes and

restrictions on female education or employment are absent. Women work alongside men

in a number of occupations. Thus gender roles reflect the unique culture that has been

fashioned from an amalgamation of the best components of various influencing cultures.

Nevertheless, the traditional gender division of labour is well defined and continues to prevail even today. The islands are dependent upon a seafaring economy. Fishing has provided the main occupation for men on the atolls. According to tradition, men go to sea to fish for tuna during the day, while women tend the home, care for children and produce food and articles for subsistence. Women on the atolls have also traditionally been involved in boiling, drying and salting fish, as well as in various local fibre-based handicrafts, including the production of coir rope and twine, matting, producing palm frond panels and basketry.

In general, two major constraints inhibit the ability of women to participate in economic activities:

Population

In 1995, the population of the Republic of Maldives, excluding foreign nationals, was 244

644 persons. An estimate for 1997 put the total population at 263 189, of which about

48.5 percent are women (Official Government Website). The Maldives has one of the

highest population growth rates among developing countries in the Asia Pacific Region.

For instance, the population grew at 2.79 percent during the 1990–1995 period.

Accordingly, the population is young; 47 percent of the population is in the under 15 year

age group, while 50 percent is in the working age group (15–64 years) and just 3 percent

is in the 65 years and older age group. Life expectancy is 70 for men and 71 for women.

The sex ratio is 105 (Fifth National Development Plan, Government of the Maldives).

Of the approximately 1 200 islands in the Maldivian archipelago, only 198 are inhabited. Five islands are industrial and 72 have been developed as tourist resorts. As much as 25.7 percent of the Maldivian population live in the capital Male' (1995 Census). Outside the capital, the population distribution among the twenty administrative atolls is relatively uniform, varying from less than 1 percent to more than 7 percent of the country's total population. There is concern that disparities in population distribution between Male' and the atolls, attributable to slower growth in agriculture and fisheries as compared to other sectors, are increasing. This trend has been described as a backwash effect' whereby Male' and the resort and industrial islands act as centres of growth, while the remaining islands act as the hinterland (ILO/ARTEP, 1993). The population distribution by age group in Male' and the atolls is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Population Distribution by Age Group in Male' and the Atolls

| Age Group (in years) | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male' | Atolls | Male' | Atolls | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| Under 1 | 2.1 | 4.4 | 2.7 | 4.3 |

| 1 – 4 | 9.7 | 16.5 | 11.3 | 15.8 |

| 5 – 9 | 12.2 | 17.5 | 14.3 | 17.0 |

| 10 – 14 | 12.0 | 12.4 | - | 12.0 |

| 50 – 54 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 3.1 |

| 55 – 59 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| 60 – 64 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| 65 and above | 1.9 | 3.7 | 1.8 | 2.2 |

Source: Population and Housing Census of the Maldives, 1990.

Education: Gender Equitable Access

The education system in the Maldives consists of seven years of basic education, three

years of lower secondary (ordinary level), and two years of higher secondary education

(advanced level). The Maldives achieved a 263 percent increase in enrolments between

1977 and 1995, from 24 203 to 87 878 respectively. Similarly, the 1995 rate of enrolment

was an impressive 100 percent, while the drop out ratio was only 7 percent. There are

no gender disparities in education at any level (Haq and Haq, 1998). Yet, on the atolls,

students are ‘forced out’ of education given the complete lack of higher education

opportunities. Although a few vocational training institutes exist at the post-secondary

level, students seeking tertiary education are required to go abroad. The government

provides overseas training for its employees.

Employment: Persisting Gender Differences

In the 1995 census, the economically active population of the Maldives stood at 66 887

persons, representing an increase of 3.1 percent per annum in the 1990–95 period. In

the same period, the number of foreign nationals working in the Maldives grew at an

annual rate of 16.5 percent to reach 18 510. Foreign nationals comprised 21.7 percent

of the total workforce in 1995. In 1995, the total rate of participation in the workforce was

43.7 percent. Yet compared to a participation rate of 63.2 percent for men, women's rate

of participation was just 24 percent. The participation rates for younger workers in the

20–44 year age group are higher in Male' than on the atolls. By comparison, for those

aged 50 years or above, economic participation rates are higher on the atolls.

Recent shifts in the Maldivian economy, characterised by a move away from primary industry towards tertiary industry, have had repercussions on employment, for both men and women. For instance, the drop in the primary sector's contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) has been reflected by a fall in the employment share of fishing, agriculture, forestry and quarrying; and a reduction in the share of agricultural and fisheries workers in the employed labour force. In contrast, the increase in the tertiary sector's share of GDP has been mirrored in increased employment in wholesaling and retailing, hotels and restaurants, as well as finance, insurance and business.

Tables 2 and 3 illustrate variations in employment distribution from 1985–90 for various economic sectors in the Maldives as a whole, and on the atolls respectively. They highlight how all those sectors which experienced a decline in their share of employment from 1985–90, also experienced a reduction in their number of employees. Furthermore, they indicate that the main brunt of reductions in employment has been borne by women in the labour force of the atolls.

According to a 1993 report by the International Labour Organization, the most plausible explanation for the decline in employment in agriculture is an under-enumeration of women engaged in agriculture (ILO/ARTEP, 1993). Since the census count enumerated the primary occupation of the respondents, women normally engaged in multiple activities may have been unable to identify any single activity as their primary occupation. Similarly, although a significant proportion of women in the atolls work in agriculture, their involvement in a range of economic activities may have made it more difficult to identify a main occupation, causing the ‘not stated’ category to be disproportionately large. In the Maldives, as in other countries within the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), women's economic work is often considered as unpaid family labour.

Table 2. Employment Distribution of Women and Men by Sector in the Maldives (1985 and 19902

| Sector | 1985 | 1990 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Number | Number | Number | Number | |

| Agriculture | 1673 | 1386 | 1438 | 1181 |

| Fisheries | 12170 | 264 | 11181 | 317 |

| Quarrying | 604 | 39 | 482 | 14 |

| Manufacturing | 5116 | 6443 | 4259 | 4182 |

| Electricity, gas and water | 500 | 4 | 409 | 36 |

| Construction | 2528 | 35 | 3109 | 42 |

| Distribution | 5129 | 306 | 8332 | 552 |

| Transport, storage and communication | 3212 | 115 | 5024 | 297 |

| Finance, insurance and business | 366 | 52 | 869 | 189 |

| Community, social and personal service | 8157 | 2274 | 8132 | 3716 |

| Total | 39455 | 10867 | 43235 | 10526 |

| Not stated | 858 | 249 | 1623 | 565 |

| Grand Total | 40313 | 11116 | 44858 | 11091 |

Source: Population and Housing Census of the Maldives, 1985 and 1990

2 For Tables 2 and 3, employment is for persons aged 12 years and over and sectors are the same as in the 1985 and 1990 censuses.

Table 3. Employment by Sector of Women and Men on the Atolls, 1985 and 1990

| Sector | 1985 | 1990 | Percentage Change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Number | Number | Number | Number | % | % | |

| Agriculture | 1600 | 1320 | 1379 | 1170 | -13.8 | -11.4 |

| Fisheries | 11289 | 256 | 10450 | 310 | -7.4 | +21.1 |

| Quarrying | 381 | 38 | 305 | 14 | -19.9 | -63.2 |

| Manufacturing | 3705 | 6030 | 3425 | 3765 | -7.6 | -37.6 |

| Electricity, gas and water | 207 | 3 | 123 | 8 | -40.6 | +67.0 |

| Construction | 1816 | 26 | 2105 | 32 | +15.9 | +23.1 |

| Distribution | 2824 | 241 | 5441 | 394 | +92.7 | +63.5 |

| Transport, communication | 1602 | 49 | 2379 | 49 | +48.5 | 0 |

| Finance, insurance | 95 | 2 | 312 | 26 | +128.4 | |

| Other services | 3709 | 860 | 3935 | 1663 | +6.1 | +93.4 |

| Total | 27228 | 8824 | 29854 | 7431 | +9.6 | -15.8 |

| Not Stated | 497 | 186 | 989 | 420 | +99.0 | +125.8 |

| Total | 27725 | 9010 | 30843 | 7851 | 11.2 | -12.9 |

Source: Population and Housing Census of the Maldives, 1985 and 1990.

Table 3 illustrates that employment lost by men in one sector has usually been gained in another. In fact, in most cases the pull of higher wages in the more rapidly growing sectors has been the driving factor explaining men's mobility. By comparison, while some of the many women who lost their manufacturing jobs on the atolls have found new work in the service sector, most have not. Thus, the number of employed women on the atolls declined from 9 010 in 1985 to 7 851 in 1990. This marked decline in female employment in manufacturing3 is in large part due to a steady decline in local demand for handicrafts products due to changes in consumer tastes and/or the use of substitute synthetic materials. At the same time, with the progressive mechanisation of the fishing industry, and a shift in the external demand for dried and salted fish, women's employment in fish processing industries has declined sharply. It is for these reasons that female employment declined in the Maldives as a whole, despite an increase in women's employment in Male'.

Tourism has been the most dynamic sector of the Maldivian economy during the last ten years and has been the source of many new jobs. For instance, resort construction and maintenance has created employment for many carpenters and masons whose skills were otherwise usually limited to making furniture and houses. Male' has grown into a major trade centre supported by the emergence of a recently developed tertiary sector providing new employment in communication, distribution, finance, other services, etc. In Male, the number of economically active women, as a percentage of the economically active population, has increased steadily from 14.6 percent in 1985 to 27.7 percent in 1995.

Yet most of the economic growth resulting from tourism and associated development has occurred in Male' or the resort and industrial islands, attracting younger and more capable men from the atolls. Consequently, the population of the atolls has a relatively large proportion of women, children and older men, and wide discrepancies are emerging in the lifescapes of people living in Male' and the atolls. These discrepancies are further reflected in declining employment opportunities on the atolls, especially for women. On the atolls, women's share of the economically active population fell in 1990, before increasing again in 1995. In 1995, two sectors continued to dominate employment on the atolls.

Almost half of the economically active population in the Maldives are employees. Yet some 36.8 percent of women are employees compared to 52 percent of men. Compared to women in Male', women on the atolls are more dependent on setting up their own business and/or working for their families in order to make a livelihood. Nevertheless, women represent only 15 percent of the total number of employers in the country.

3 In employment statistics, manufacturing includes fish processing.

Women Employed by the Public Sector

Since 1990, women have accounted for almost one third of government employment.

For instance, the Ministry of Fisheries and Agricultural (MoFA) has 127 employees, 25

percent of whom are women. The senior level in this Ministry comprises 24 percent of

the total number of employees and women represent 25 percent of staff at this level.

The highest-ranking post held by a woman is that of Deputy Director. Table 4 illustrates

women's and men's employment in senior government positions. There are no

distinctions in public sector employment terms and conditions for men and women in the

Maldives. Given the lack of variation in women's relative participation at all levels, there

appears to be no discrimination in employment in the MoFA. Nevertheless, all MoFA

field officers are men. While the government shows no preference for men or women

field workers, women do not generally apply for out-posted jobs, in large part as a result

of their household and family responsibilities.

Table 4. Employment of Men and Women in Senior Government Positions

| Governance Level | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| Minister | 95 | 5 |

| State Minister and State Dignitary | 100 | 0 |

| Deputy Minister and others at same level | 100 | 0 |

| Director Generals and others at same level | 92 | 8 |

| Officer at the NSS | 100 | 0 |

| Director and others at the same level | 86 | 14 |

| Deputy Director | 86 | 14 |

| Assistant Director | 78 | 22 |

| Technical Posts at the Under-Secretary level | 68 | 32 |

Source: Directory of Women in Senior Government Positions 1996, MWASW.

Table 5 illustrates women's and men's employment in different public sector institutions. It highlights extremes in women's and men's participation rates in certain types of occupations and appears to indicate a preference among women for certain types of work. Reflecting traditional social norms whereby women are primarily responsible for raising and caring for children, women tend to be more represented in nursing, education and allied activities.

Table 5. Comparative Employment of Men and Women in the Public Sector

| Government Office | Men (% of total employees) | Women (% of total employees) |

|---|---|---|

| Female Participation < 20% | ||

| Addu Development Authority | 88.43 | 11.57 |

| Anti-corruption Bureau | 80.95 | 19.05 |

| Maldives Electricity Board | 94.17 | 5.83 |

| Maldives Industrial Fisheries Company | 91.43 | 8.57 |

| Female Participation > 60% | ||

| Bank of Maldives | 37.50 | 62.50 |

| Chest Clinic | 25.0 | 75.0 |

| Institute for Health Sciences | 10.13 | 89.87 |

| Maldives Post Limited | 33.90 | 66.10 |

| Malé Health Centre | 11.11 | 88.89 |

| National Library | 28.0 | 72.0 |

Source: Directory of Women in Senior Government Positions, MWASW.

Lifescape: Distinct Life Styles in Urban Male and the Atoll Communities

The preceding sections have highlighted some of the differences in livelihoods,

employment and lifestyles of the residents of the capital Male' and the atolls. In general,

the communities living on the atolls continue to practice a more traditional way of life

compared to the people of Male'. As the centre of governance and trade activities, Male'

offers women and men employment in the public and tertiary sectors. Public sector

employees are permitted to take a second job and men tend to be involved in second

businesses to earn additional sources of income. Women, on the other hand, have

limited extra' time and tend to assume responsibility for household and child care duties

after working hours.

The people of Male' have easy access to foreign goods imported for the resorts. The trend is to consume rice, wheat, cereals, powered milk, etc. Fish remains the staple source of protein, and in some households dals/pulses are also prepared. A number of the people living in Male' have been abroad for higher education, and have often developed a taste for international foods. For instance, canned drinks and foods are popular and are easily found in food stores.

Male has 24 hour electricity, good basic education facilities, a few vocational training centres and excellent health services. On the other hand, it is extremely congested, and housing is very expensive. The local water supply is brackish and must be desalinated for drinking. Solid waste and sewage disposal systems are beyond the current capacity of the island. Entertainment in Male' includes home videos, sports such as football or tennis walking along the marina, night fishing, day visits to the resort islands, etc.

Maldivian Gender Roles in Bio-resource Management

Outside Male', on the outer islands, people's lifestyles are very different. In particular, there is a greater dependency on local resources among atoll communities. Given the large-scale migration of men aged between 15–40 years to Male' or the resort islands in search of employment, the availability of male labour is in scarce supply on the atolls. This has attendant effects on agricultural production, particularly in male-dominated production activities such as coconut harvesting. In general, there is a larger proportion of men on the fishing islands, than on islands where agriculture is the main occupation. Women tend to operate small income generating ventures, such as eating houses, shops, tailoring units, etc. and are responsible for managing the household, home gardens and small agricultural plots. Women are also responsible for teaching children the basics of the Koran and Dhivehi, as well as simple arithmetic in the non-formal education centres.

Timber and fuel wood needs are met by individual islands, except in special cases of boat-building where uninhabited islands are visited to harvest appropriate timber. Each island has a plot reserved for the cultivation of fuel wood and timber species. Areas are also earmarked for agriculture and housing. The remainder of the island is left as wilderness. The house reef is well protected. Coral stones washed ashore are used for construction and lime production. While in earlier times, entire houses were made of coral, now legislation only permits corals to be used for the boundary walls in order to safeguard the reef. Given the resort islands now provide the only market for reef fish, there is very little fishing within the reef. Tuna fishing, the mainstay of fishing families, is carried out in the open seas.

Food habits on the atolls are more in tune with local produce. Though rice and wheat flour have reached the palate of every Maldivian, tubers such as cassava, taros and sweet potatoes, and bread fruit are consumed with greater frequency on the atolls. Fish curry, together with fish soup and its concentrate (rihakaru) are very popular.

On the atolls, higher education is not always available, health facilities are minimal and people often have to travel by boat to the main island to gain medical attention. Ferry services between the islands are dependent on demand, as well as weather conditions. Yet, although the islands do not possess adequate electricity, education and health facilities, compared to Male', there is ample land for housing, good water quality, a variety of local foods and a better quality of life. Entertainment is in the form of home videos, evening walks along the beach, discussions at the mosques, meetings of the island committees, and visits to Male'.

The Republic of Maldives is governed by a Citizens' Majlis or Parliament which is elected for five-year terms. The Majlis comprises fifty members (two elected from each Atoll, two from Male' and eight nominated by the President) and has the President as its leader. Historically, the 26 natural atolls have been divided into 20 administrative units or atolls. Each atoll is administered by an Atoll Chief and an Atoll Administration with the assistance of elected Island Committees which include women's committees. The island of Male' is a separate administrative division.

A national development plan is prepared every third year to foster the planned development of the country. The Fifth National Development Plan (1997–2000) identifies the following nine key priorities, within three overall areas, to receive particular attention:

Management and development of human resources

Establish sustainable and equitable provision of infrastructure and delivery of services and facilities

Planned human settlement

National biodiversity management in the Maldives is the responsibility of both the Ministry of Planning, Human Affairs and Environment (MPHRE) and the Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture (MoFA). The Environment Division of the MPHRE is responsible for the development of national guidelines, policies and legislation, as well as follow-up to international conventions and conferences. An Environment Research Unit has been formed to undertake research related to environmental protection. The National Commission for the Protection of the Environment (NCPE) acts as an independent advisory body to the MPHRE.

The Marine Research Section was established in the Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture in 1983 with the purpose of carrying out research and experiments on the expansion and improvement of the country's fishery industry. Its mandate has enlarged significantly beyond its initial responsibility.