"Before IPM field schools we planted our rice and prayed that we might have a good harvest. Now we know that we can actually control many of the factors which influence our harvests."

An IPM farmer from Thai Binh province, Viet Nam

Over two million rice farmers in Asia and Southeast Asia participated in rice integrated pest management (IPM) farmer field schools (FFS) between early 1990, when the first FFS was conducted in Indonesia, and the end of 1999. During those 10 years, farmers, agriculture extension field workers, plant protection field workers and NGO field workers learned how to facilitate the FFS approach and conducted over 75 000 FFSs. Farmers who have participated in field schools have reduced their use of pesticides, improved their use of inputs such as water and fertilizer, realized enhanced yields and obtained increased incomes. From this beginning they moved into other crops and wider ranging activities related to their agro-ecosystems. IPM alumni are in the forefront of establishing sustainable agricultural systems in their villages and promoting food security for themselves, their children, and generations to come.

The IPM farmer field school has become a model approach for farmer education in Asia and many parts of Africa and Latin America. The approach has been used with a wide range of crops including cotton, tea, coffee, cacao, pepper, vegetables, small grains, and legumes. The FFS has proven effective at involving a wide range of people in the learning process, from school kids to the handicapped. The goal of this book is to set forth the educational and ecological principles underlying the IPM FFS, explore the strategy known as community IPM and discuss issues related to the community IPM project or programme implementation. The book ends with a brief look at future possible directions and how community IPM can address sustainable livelihood issues.

IPM field schools do not focus on insects alone, they provide farmers an opportunity to learn and achieve greater control over the conditions that they face every day in their fields. Farmers are thus empowered by field schools. Empowerment is a fundamental element in a civil society and it is the principle that has influenced the design and implementation of farmer field schools.

Why empowerment? Farmers live and work in a world where they face a variety of contending forces including those related to technology, politics, markets and society. These forces can marginalize farmers if they are not proactive. Farmers need to be able to make their voice heard now as sustainable ecological agriculture approaches a critical crossroads. Contending technologies are presented to farmers. Most of these technologies are not developed with the goal of improved farmer welfare; the goal is increased aggregate national production and profits for those who promulgate the technologies. Farmers need to be able to select technologies that benefit them and contribute to overall food production. They must also be able to transform and evolve any chosen technology to fit the specific ecological and economic conditions confronted by them. Agriculture is often the focus of political activity. Whether at the national or village level there is frequent debate over issues that affect the livelihood of farmers. The rights of farmers, access to land and water, decisions on cropping patterns, subsidies, and price supports are a few examples of the myriad issues that affect farmers. Those who would make decisions regarding these issues, although they might claim otherwise, do not always recognize or understand the interests of farmers. Farmers need to be able to understand the issues affecting their livelihood and contend in the debates these issues generate to guarantee that their interests are served.

Farmers, in many societies, are at the lowest rung of the food production ladder. Marketing systems generally do not operate in their favour. Farmers are placed in the position of being price takers. There are strategies that farmers can use to change this situation. Farmers need to be able to analyse, understand and maximize their leverage regarding market factors.

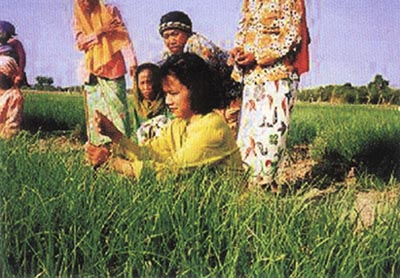

These Farmer have organized a cooperative seedling bed. The narrow plots allow farmers to collect stemborer egg messes.

Besides being at the lowest rung of the production ladder, farmers, while often romanticized, are just as often referred to pejoratively. Commonly used terms include "peasants", "villagers" or "farming community". These terms tend to objectify and deny the individuality of farmers. The Green Revolution reinforced this by creating extension systems based on social engineering that regarded farmers as another production factor, much like fertilizer. Farmers were often deprived of the right to make decisions regarding their livelihood by heavily centralized productionoriented command systems serving national production targets, not farmers' interests. These systems frequently made mistakes that endangered food production. Educated farmers can make more effective decisions regarding food production at the field level than can centralized bureaucracies, while also proposing and promoting policies that reflect local reality.

The IPM movement, a programme strategy based on empowerment, has helped farmers to move from the margin into a more powerful position vis-à-vis these technical, political, market and social forces.

FFS participants:

Learn and can apply ecological principles to better manage their crops within their own specific agro-ecosystem;

Master and apply critical thinking skills at both farm and community levels;

Acquire leadership skills that they apply in organizing collaborative approaches to local ecosystem management;

Master applied discovery approaches that allow them to gather, systematize and expand local knowledge.

The FFS approach fosters this learning with the intention that graduates will increase their control over technologies, markets, relevant agricultural policies and their agro-ecosystems. IPM activities assure that more farmers are making better decisions at the field level. At the inception of IPM training activities in Indonesia in 1989 there was a frank discussion about the values inherent in the design of the IPM farmer field school. The idea that FFS farmers can and should empower themselves because of their IPM FFS experience became the acknowledged motivating force among programme developers and field staff. Across Asia, ten years later, farmer empowerment continues to be the foundation of IPM activities.

The following are two brief cases involving IPM alumni from Indonesia and Viet Nam. The farmers present their comments on what they learned in field schools, what they are doing because of what they learned, and how their lives have changed. The first case is an interview of two women who farm small plots in Indonesia (Agus Susianto et al. 1998, p. 82)

|

Box 1.1 A tale of two farmers This is the story of two women who are neighbours in the village of Sempor Lor, Probalinggo district, Central Java, Indonesia. One of the women, Romini, participated in a field school, the other, Sunani, did not. Romini, 45 years old with four children, farms her family's rice fields. Her husband works as a trishaw driver; his farming activities are limited to field preparation and harvesting. She takes care of all of the other farming activities. She has been growing rice since she was a child. Romini

"My husband's income is not enough for us to live on. The area I farm is only 750 m2. I have been interested in finding a way to farm effectively so that my yields might be as high as possible. I was happy when I was asked to be one of ten women to participate in a field school in the rainy season of 1995-96. "Before I took part in the field school I farmed the way my parents had taught me. I used urea and TSP and applied the insecticide Diazinon three times a season. I usually made applications just after transplanting to control brown planthoppers. Later, when rice seed bugs would appear, I sprayed again. Finally, at the point just before harvest, I would put on a final application to ensure against damage before harvest. I averaged between 200 and 300 kg of rice per season on my small plot. "After attending the field school I changed my approach to farming. I learned that by applying insecticides I was increasing my costs as well as increasing my risks. Insecticides kill both pests and natural enemies. If I don't spray, the natural enemies do my pest control work for me. The field school also helped me to learn about balanced fertilization and planting distances. I first started to apply IPM principles without telling anybody. My yield for the first season went up to 350 kg. Since then I have averaged around 400 kg. "I now meet with women's groups and tell them about IPM principles and the dangers of insecticides. I tell the farmers in the fields around me to watch what I am doing and learn from me and not to stick with outmoded ways. No one near me is applying any insecticides." Sunani and her husband, Sumarto, have two children. They live next door to Romini. Sumarto works as labourer in construction and is available for farm work only during field preparation and harvesting activities. Sunani takes care of all of the rest of the fieldwork. "My rice field is about 1000 m2. My yields in the past averaged from 400 to 500 kg per season. What I know about farming I have learned from my parents, the extension worker and my neighbours. Many of my neighbours are well educated and have learned a lot about farming. I had a chance to follow a field school, but my mother was sick and I couldn't. Romini has told me much about IPM. Sunani

"For example, I am now using urea tablets, SP 36 and KCL. KCL is something I never used in the past. I am planting at a distance of 25 cm × 25 cm so that I can get more productive tillers. I learned that insecticides are dangerous and a waste of money and I no longer use them. I am also planting the same varieties as my neighbours and not using pesticides. Romini has taught me how to do field observations to look for pests and natural enemies. "Since I have begun applying IPM principles my yields have gone up. I am now averaging between 600 and 700 kg from my plot. I am very happy because of this." |

The following is an interview with a group of women farmers from Dong Phi village in Ha Tay province in Viet Nam (Pontius 1999). The respondents, a group of six women, have all completed IPM field schools. These alumnae discussed what they were doing differently because of their participation in IPM field schools.

|

Box 1.2 Changes Why did you attend field schools rather than your husbands? "Our husbands work in construction and as day labourers outside of the village; this brings in cash to our households and is important. Because they are often away from home we take on the responsibility for farming. Our husbands usually are present for land preparation and harvesting, but we make the day-to-day decisions regarding the management of our fields."

Did you teach them about IPM? And if yes, how? "Our husbands needed to know about IPM. This was all new information and we learned new ways of doing things. If we were to change our ways, our husbands had to know what we were doing and why." "I would take my husband out to the field and show him different insects and talk to him about their functions." "I tried out different fertilizer practices and showed my husband what I was doing and then we weighed the results from each of our different trials." "Yes, I had to make sure my husband wouldn't be afraid because I wasn't applying pesticides. This meant I had to take him into the field and show him how the ecosystem worked." "Because I was buying more fertilizer my husband wanted to know what I was doing. So I talked to him about fertilizer and balanced fertilization. Then after harvest, the first season after I attended the field school, my husband could see the results of better fertilization. Our yield was fifty percent higher than before." In general how have your yields been since attending field

schools? "I think all of our yields have gone up." (All the women nod in agreement.) "Perhaps each of us has experienced different levels of increase in our harvests, but we have all seen better harvests since attending field schools." What are you doing differently? Why have your yields gone up? "I am doing things that I learned about in the field school. I use a different variety of rice. I am planting fewer plants per hill and the hills are farther apart. This allows each plant to produce more productive tillers with more rice grains. I am using less urea but more phosphorus and potassium." "I think that we are also paying more attention to using water effectively." Tell me about other ways in which having attended a field school has changed how you live. "I think we women work better together as a group. Our discussions are more open and we make sure everyone of us gets to say what she is seeing in the field and gives her opinion about her observations." "I think my husband and I are a little more careful in our decision making, more analytical. For example, my husband thinks we need a motorcycle. I agree that it would be useful. But rather than buying the motorcycle right away, we have analysed how we would benefit because of a motorcycle and what we would have to give up because of buying a motorcycle. Also we are examining how to purchase the motorcycle, credit or cash." "I go to sleep easier at night. Before my husband and I didn't know much about what was going on in our field. Now we make better, more informed decisions. We know about different factors in the field such as pests, natural enemies, fertilization, and we know how to care for our crop. We can actually take control of many things to ensure better yields. This makes me sleep easier." |

Writers and researchers with backgrounds in non-formal, adult or extension education have observed and written about the field school approach. The following is a brief collection of their comments on field schools.

|

Box 1.3 The basis of training "The basis for the training approach... is non-formal education, itself a learner-centred discovery process. It seeks to empower people to solve living problems actively by fostering participation, self-confidence, dialogue, joint decision-making and self-determination. Group dynamic exercises are an important part of this approach. "Discovery learning by farmers on the basis of agro-ecosystem analysis, which uses their own field observation, is science-informed. The agro-ecosystem analysis methodology was developed carefully on the basis of the latest entomological knowledge. Hence this participatory approach does not represent a violation of the integrity of science, but rather a new interactive way of deploying science." Roling and van de Fliert in Facilitating sustainable agriculture |

|

Box 1.4 The key principles of farmer field schools 1. What is relevant and meaningful is decided by the learner and must be discovered by the learner. Learning flourishes in a situation in which teaching is seen as a facilitating process that assists people to explore and discover the personal meaning of events for them. 2. Learning is a consequence of experience. People become responsible when they have assumed responsibility and experienced success. 3. Cooperative approaches are enabling. As people invest in collaborative group approaches, they develop a better sense of their own worth. 4. Learning is an evolutionary process and is characterized by free and open communication, confrontation, acceptance, respect and the right to make mistakes. 5. Each person's experience of reality is unique. As they become more aware of how they learn and solve problems, they can refine and modify their own styles of learning and action. Jules N. Pretty, Regenerating agriculture |

|

Box 1.5 Economic benefit and enhanced decision-making capacity The well-proven reduction of insecticide use by FFS graduates, the stable or even increased yield and the reduced risk for farmers following the IPM principles imply that farmers are directly profiting from the programme [the Indonesian national IPM programme which was responsible for the IPM training project employing field schools]. Over and above, FFSs have two main results: farmers regain the competence to make rational decisions concerning the management of their crops (in contrast to the instructions which were part and parcel of the Green Revolution packages). Secondly the participants gain social competence and confidence to speak and argue in public. Farmers are owners of the programme The enthusiasm of FFS graduates in general and of farmer trainers in particular indicates that they have become the driving force and the owners of the programme. This is for example expressed in the steps to found a farmer trainers' association or in the remark of a senior trainer: it's their - the farmers' - programme, not ours.' Increased local funding The emergence of stable interest groups as a consequence of FFSs and the increasing readiness of local authorities to contribute to the funding of FFSs are indicators that the introduction of IPM has become sustainable and will continue even after the termination of foreign funding. Peter Schmidt, Jan Stiefel, Maja Hurlimann, Extension of complex issues |

The central lesson emerging from IPM farmer field school implementation over the past decade is that the complex ecological and social context of IPM argues for a sustained effort combining elements of technological development, adult education, local organization, alliance building, and advocacy. Scientific excellence and adherence to ecological principles provide a strong technical entry point for IPM development. The application of participatory, non-formal adult education methods represents a real advance over models based on information dissemination and the delivery of simple messages. But this is not enough. The long-term development of a sustainable small-scale agriculture also requires strong farmer groups with linkages among them and with the wider community.

From this perspective, IPM farmer field schools are not an end in themselves; they are a starting point for the development of a sustainable agricultural system in a given locality. The FFS provides farmers with an initial experience in experimentation based on ecological principles, participatory training and non-formal education methods. Once this foundation has been laid, farmers are better able to act on their own and to sharpen their observation, research and communication skills. The FFS sets in motion a longer-term process, in which opportunities are created for local leadership to emerge and for new, locally devised strategies to be tested. This longer-term process has been identified as community IPM.

Community IPM is a strategic approach whose goal is to institutionalize IPM at the community level. Like the sustainable livelihood approaches that have been gaining attention, community IPM assumes that all rural people, even the poor, have assets. In this analysis assets can be described in terms of five categories of capital: natural, human, social, physical and financial. Community IPM activities are intended to:

Create and strengthen social capital in rural communities by supporting farmers' own efforts to build associations and networks that give them a voice and an improved means of helping each other.

Create and strengthen human capital in rural communities by supporting farmers' own efforts to train other farmers using content and methods that promote critical thinking and improved decision-making.

Preserve and restore natural capital in rural communities by supporting farmers' efforts to carry out studies and implement farming practices (as individuals and as groups) that take account of ecological processes.

Lay a foundation for future improvement in the financial and physical capital of rural communities by creating and strengthening structures and processes which will expedite the provision and management of credit and the construction and management of facilities such as village laboratories and training centres.

Strategies based on this analysis are helping farmers across Asia to create their own approaches to the further development and institutionalization of IPM in their villages.