"Available information has shown that economic activities of rural Cambodians are almost fully dependent on natural resources such as agriculture, forestry and fisheries."

SAM Nouv

LIENG Sopha

THOR Sensereivorth

Department of

Fisheries

Cambodia

Inland fisheries in Cambodia play a more important role than the marine fisheries sector and contribute 90% of the total fish production. Fisheries information and statistics is important for planning the development and management of the fisheries and understanding fisheries contribution to the national GDP. Information on the economic value of the fisheries will attract the attention of managers, government officers, NGOs and other stakeholders and help persuade them to maintain the status of resources and to protect the interests of resource users. Given the significant contribution of fisheries resources to food security, there is an urgent need to maintain sustainable management of these resources through policy and program decision-making.

Available information has shown that economic activities of rural Cambodians are almost fully dependent on natural resources such as agriculture, forestry and fisheries. The inland fisheries support a thriving industry of great economic and social importance (Van Zalinge et al. 2000a). However, lack of understanding has resulted in neglect and some development activities have caused Cambodians to suffer from seasonal water shortages and lower domestic water quality from livestock and human waste, fertilizers and pesticides used in agriculture production and waste discharged from industry.

These and other changes have put considerable stress on water resources and the aquatic ecosystem (Jady, 2001). In addition, the construction of dams, navigation channels, irrigation, river canalization and diversions and burned and bunded road networks have caused a reduction in fish production by altering fish habitats, changes in nutrient levels and blocked fish migration routes between feeding, breeding and nursing grounds (Jady, 2001).

This paper will discuss the development of a new approach to improving inland fisheries information, which will further our understanding of the current status and trends in inland and capture fisheries.

Importance of inland fisheries in Cambodia

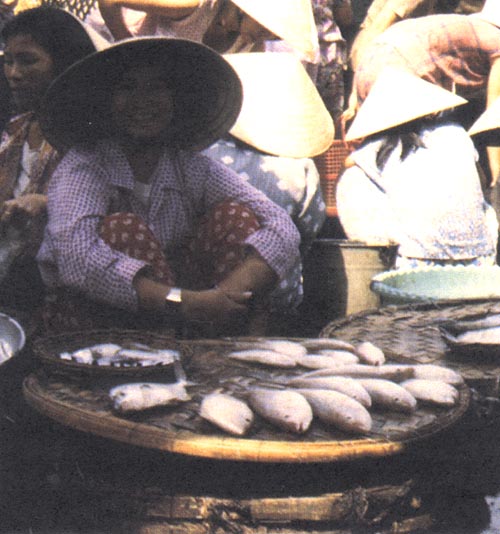

Fish in Cambodia is essential for providing food security to the people. Fish and fisheries products are part of the daily diet. Fish are smoked, fermented, dried, salted, made into fish sauce or served fresh. Fish can be found almost everywhere in Cambodia and provide high nutrition in the diet and are easily digested.

The fisheries also provide employment. About 85% of Cambodian people are rural farmers and most of them are full or part-time fishers. At least 2.3 million people are engaged in fisheries-related activities. The fisheries provide direct job opportunities to fishers and other related activities such as fish marketing, netting, making fishing gears, fish processing and so on.

The fisheries provide revenue to the government and income generation to the people. The government collects fishing fees from large and medium-scale fisheries. The estimated value from all types of fisheries could be US$ 200-250 million for the estimated fish catch range from 290 000 tonnes to 400 000 tonnes. Under the government policy to reduce poverty, free fishing rights have recently been given to medium-scale fishers.

Status of inland capture fisheries

The administrative structure

The responsible body for collection and compiling fisheries data and information is the statistical section of the Department of Fisheries. The statistics so far have been taken from provincial fisheries offices ranging from aquaculture, inland and marine fisheries (Fig. 1). The provincial fisheries offices also compile reports from their own fisheries districts through logbook recordings. Lack of funds, skills and techniques have been obstacles for statistical data collection and analysis. The available statistics so far are not reliable and need to be improved.

Fig. 1. Old system of data collection and compilation

Since the beginning of the DoF/MRC Capture Fisheries Project between the Department of Fisheries and the Mekong River Commission in 1994, data and information on fisheries has improved and is more reliable. The Department of Fisheries has a better understanding of the status of the inland fisheries both on biological and ecological aspects.

Part of the overall activity of the DoF/MRC Capture Fisheries Project was the assessment of fish catch and value from fisheries. The project applied a stratified sampling scheme. The estimate was the fish catch by month, by gear, by season, by district, by province, price and value for large and medium-scale fisheries. The administrative structure of the project for data collection and analysis is shown in Fig. 2. The first comprehensive socio-economic survey on small- and medium-scale fisheries was carried out in 1995/96. The estimate covered mainly the central part of Cambodia. This system of operation ended when the project was phased out. However, Provincial Fisheries Office staff were trained by the Capture Fisheries Project and have the field level skills.

Fig. 2. Project system of data collection/compilation

Habitat types and water resources

Cambodia comprises a wide range of habitat types including marshes/swamps, flooded grasslands, flooded forests, flooded shrub lands and rice fields. All of these habitats are situated in the central floodplain of Cambodia, which is the main fishing ground. The flooded forests cover the largest areas after rice fields and it is believed that they make a large contribution to fish production (Table 1).

Table 1: Land and water resources in Cambodia

Source: Mekong Secretariat 1995

* Water surface refers to dry season levels. Wet season central floodplains cover an area of 23 400 square kilometers.

|

Types of Land and Water Resources |

Area (Km2) |

% |

|

Water surfaces |

4 111* |

18.3 |

|

Marshes/swamps |

29 |

0.1 |

|

Flooded grasslands |

849 |

3.8 |

|

Flooded forest |

3 707 |

16.5 |

|

Shrub land |

13 501 |

60.0 |

|

Receding rice fields |

293 |

1.3 |

|

Total |

22 490 |

100 |

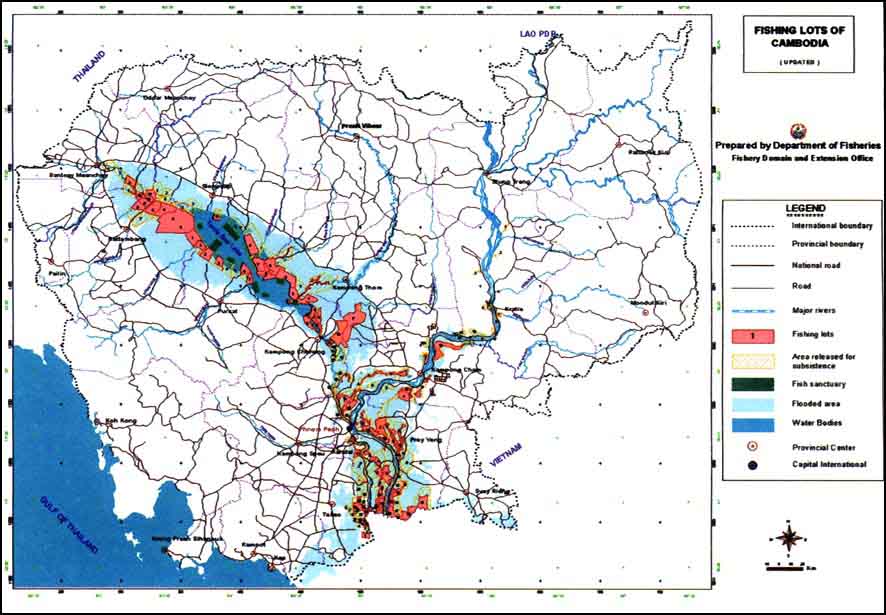

The availability of fish habitats in Cambodia is influenced by the flood regime of the Mekong River. The flood regime influences the changes in the extent of the floodplain area (Fig. 3). The total area of water bodies is much smaller in the dry season. Understanding the types of water resources and the area they cover may provide clues for the estimation of fish yield and production in relation to these habitat types.

Fig. 3. Extent of floodplain in Cambodia

Fish species and the fisheries

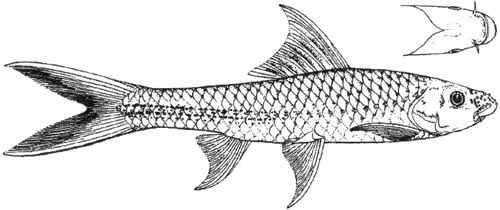

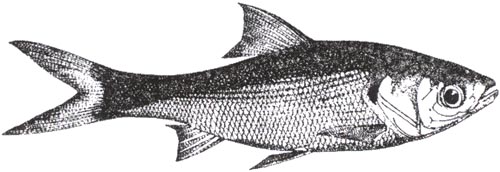

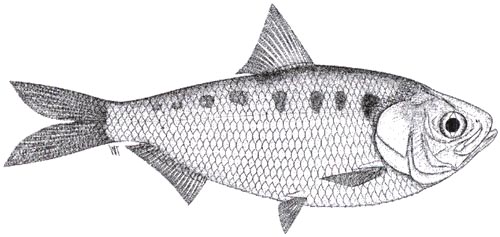

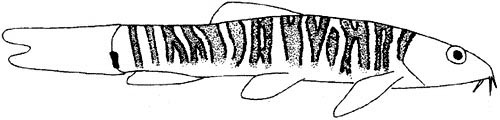

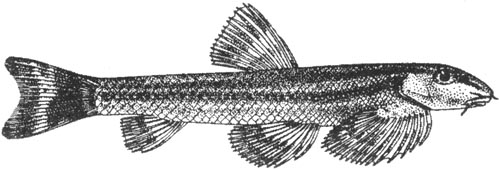

Cambodia is rich in fish species. About 100 fish species are commonly caught every year in the Tonle Sap floodplain (Van Zalinge et al. 2000b). About 500 fish species have been identified. The variety of fish species is due to the wide range of fish habitats, the complex ecosystem and the geological characteristics of the system which provides a rich supply of food and breeding grounds. The zone has high biological productivity and provides important nurseries for fish breeding. Many fishing gear types and fishing methods have been developed to catch the many different species of fish. Gears range from stationary to fixed gear in flowing water and stagnant water bodies. Fishing takes place in two seasons: open (October-May) and closed (June-September). These fisheries can be categorized into three levels:

1) Large-scale (industrial) fisheries: can operate in limited access areas. There are two types of large-scale or industrial fisheries: fishing lots and bagnet fisheries. The fishing lot or barrage fisheries sell fishing rights through an auction system. There are currently 164 fishing lots consisting of 82 riverine and lacustrine fishing lots, 60 bagnet (dai), 8 dai trey linh bagnet fisheries catching Thynnichthys thynnoides, 13 shrimp fishing lots, and 10 beach fishing lot. There are 13 fish sanctuaries.

2) Middle-scale (artisanal) fisheries: operate in open access areas only during the open season. About 200 types of fishing gear have been identified and about 40 gear types are used in most fishing grounds. Ten fishing gears are most commonly used.

3) Family (subsistence) fisheries: operate in open access areas year round and in limited access areas during closed fishing season and in flooded rice fields.

These artisanal and family fisheries have rapidly increased in the past two decades leading to over-fishing.

Fish production

The estimated fish production in Cambodia varies. One factor is the extent to which estimates of fish production include all varieties of gear types at all times and in all areas. Not all the fish caught pass through markets and are not recorded. Rural people who catch fish in small amounts for family consumption were previously not considered. There was no statistical monitoring system for these household fisheries and therefore information on capture fisheries may not reflect the actual production.

The most recent and most reliable fish statistics in Cambodia come from the collaborative MRC and Fisheries Department project. These reasonably accurate statistics point to the significant contribution of the fisheries sector to the rural economy and the social requirements of rural people (Van Zalinge et al. 2000a). These statistics are increasingly important for decision-making on options for the development of the national economy.

The most comprehensive data and information are from the MRC/DoF socio-economic and catch assessment surveys conducted in parts of the country (Ahmed et al. 1998, Van Zalinge et al. 2000b). These surveys indicate that:

Cambodia's freshwater capture fisheries production is over 400 000 tonnes/year.

Estimated value at landing site is around US$ 200 million. The estimated retail value is about US$ 300 million. Exports are underestimated, but exceed 50 000 tonnes/year (Van Zalinge et al. 2001). Countrywide fish consumption is around 30-40 kg/person per year.

The average per capita fish consumption in central Cambodia is 67 kg.

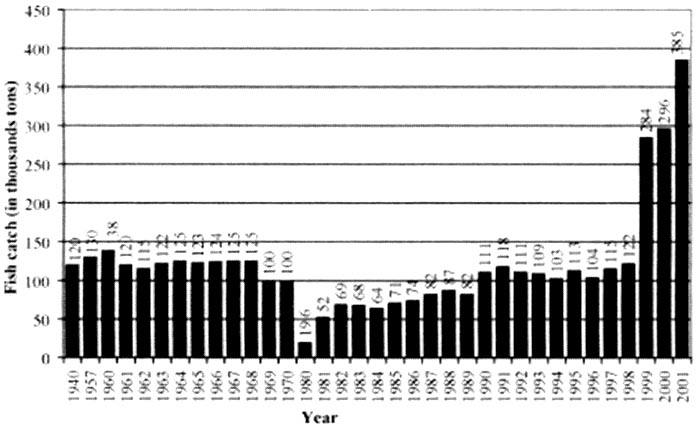

The Department of Fisheries has adopted a level of fish production slightly lower than the capture fisheries project estimate. This is twice or triple past estimates. This may be a result of underestimation of the fishing effort and an increase in the gear used in the past two decades (Fig. 4).

Suggestions for the improvement of fisheries statistics

As a majority of the population lives under the poverty line, the government focus is on poverty alleviation. Fisheries information is important for identifying key strategies for sustainable development and management, but is given low priority. Up to the present there are insufficient government funds allocated for fisheries research and information purposes. Therefore, support to fisheries information has so far come from international sources.

Fig. 4. Estimated inland capture fish production from 1940 to 2001

The local staff working in the field of data collection and handling still have insufficient capacity. With assistance from DANIDA through the Mekong River Commission, the capacity of local staff has improved and progress on improvement of data collection and information has been made. There is more available fisheries information at present compared to the past but it still does not satisfy the requirement. To ensure the sustainability of continuous and reliable data and information, DoF needs continuous international assistance and special techniques to gather information.

Among the current fisheries issues, research activities need to be formulated to serve the following purposes:

To prevent the use of destructive fishing methods and harmful use of pesticides

To establish suitable fish sanctuaries and dry season refuges

To increase ecological knowledge, particularly fish habitats such as deep pools and spawning and feeding grounds to formulate habitat protection measures (conservation zones or fish sanctuaries) and maintain aquatic ecosystems

To assess the status of fish stocks so that measures can be taken to ensure sustainability

To promote understanding of biology of fishes in Cambodian ecosystems, in particular information on fish migration to maintain and restore fish migration routes

To serve the need for information for formulating management and strategic planning

To meet the above needs for fishery information with limited funds for operation, there should be a focus on:

CPUE

Potential fish species, their status and species under threat

Catch and value

Fish consumption

Fish yield

Ecological information

Fishing effort (number of gears, days, gear types, number of fishers

Quantity of export of fish and fishery products

Catch assessment should be considered to obtain this information. Catch assessment can be estimated based on groups of gear types instead of by individual gear types and groups of species (local species name instead of individual species name). This may be done once every three to five years to reduce costs and coud be conducted according to ecological characteristics such as:

Tonle Sap area (Kampong Chnang, Pursat, Battambang, Kampong Thom and Siem Reap)

Highland area (Kratie, Stung Treng, Ratanakiri and Mondulkiri)

Southeast of Phnom Penh

Southwest of Phnom Penh

Northeast of Phnom Penh

Flood plain area south of Phnom Penh

The estimation of fish capture can also be based on fish consumption surveys in these areas in fishing communities, provincial capitals, distances from water bodies plus export of fish and fisheries products.

The catch can also be assessed based on habitat types. When the fish yield for each habitat type and the area is known then total catch can be estimated (Table 1).

CPUE is also an important indicator for estimating the status of fish stocks. This may be done once every three years representing each sub-catchment area.

Fish species surveys also need to be carried out focusing on identifying new species and those with export potential. At the same time, there is also the need to identify species under threat for conservation and management purposes.

To facilitate statistical compilation, responsibility should go to a body with technical knowledge of data collection and compilation of fisheries statistics, hopefully, the Inland Fisheries Research Institute of Cambodia (IFRIC) at the Department of Fisheries.

Other information such as number of gears, ecological knowledge of fish habitats, fish migration, and spawning grounds are also important for formulating study projects.

General recommendations for improvement of information on the status and trends in the inland capture fisheries:

1 Train involved personnel in statistical data and information handling techniques

2 Further strengthen communication and cooperation between FAO and the Department of Fisheries for exchanging information

3 Use cost effective methods to get data and information to fulfill necessary requirements

4 Build awareness among fishers to cooperate in providing more accurate data and information

5 Set up an information gathering network as a coordination mechanism for the compilation of fisheries information

6 Provide the necessary facilities, equipment and budget needed for data and information collection and analysis

7 Seek international technical and financial support for the fisheries information operation

8 Establish good cooperation and communication with all relevant agencies and institutions for information exchange

Bibliography

Ahmed, M., N. Hap, V. Ly, and M. Tiongco. 1998. Socio-economic assessment of freshwater capture fisheries of Cambodia. Report on household survey. Mekong River Commission, Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Ahmed, M. and P. Hirsch (Eds). 2000. Common property conference in the Mekong: Issues of sustainability and subsistence, ICLARM Study Review 26, 67p.

Department of Fisheries. 1999. Outcomes of national seminars for ASEAN-SEAFDEC Conference on sustainable fishery for food security in the new millennium: Fish for the people, 19-24. November, 2001, Bangkok Thailand.

Nao Thuok and Sonam. 2000. Cambodia's freshwater fisheries management: Current status, major issues and recommendations. Cambodian Department of Fisheries.

Smith, J. D. (Ed). 2001. Biodiversity, the life of Cambodia: Cambodian biodiversity status Report 2001. Cambodia Biodiversity Enabling Activity. Phnom Penh, Cambodia. pp. 30.

Van Zalinge N., Nao Thuok and Sam Nuov. 2001a. Status of the Cambodian inland capture fisheries sector with special reference to the Tonle Sap Great Lake. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Department of Fisheries.

"Inland fisheries play an important role in providing food and jobs. It is estimated that about 20 million people rely on fisheries in China."

Shouqi XIE

Zhongjie LI

State Key Laboratory for

Freshwater

Ecology and Biotechnology

Chinese Academy of Sciences

Wuhan,

Hubei, P. R. China

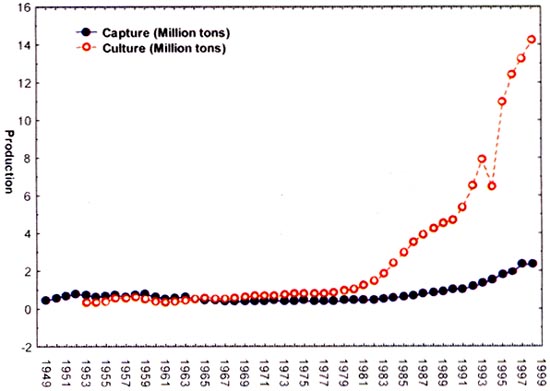

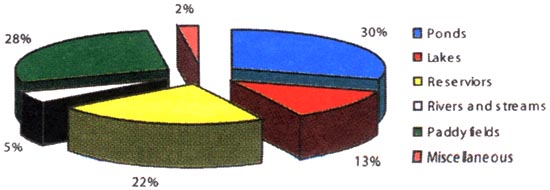

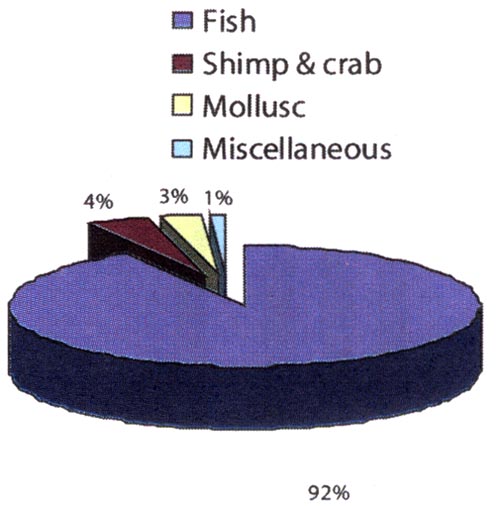

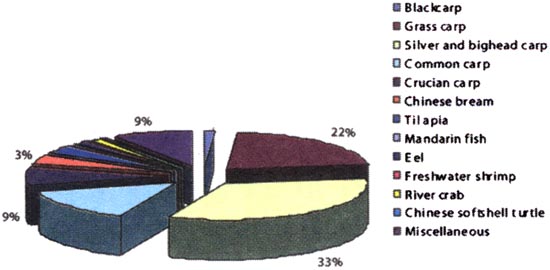

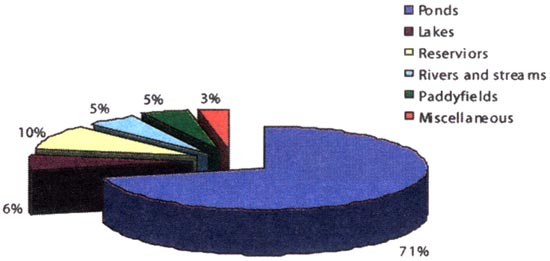

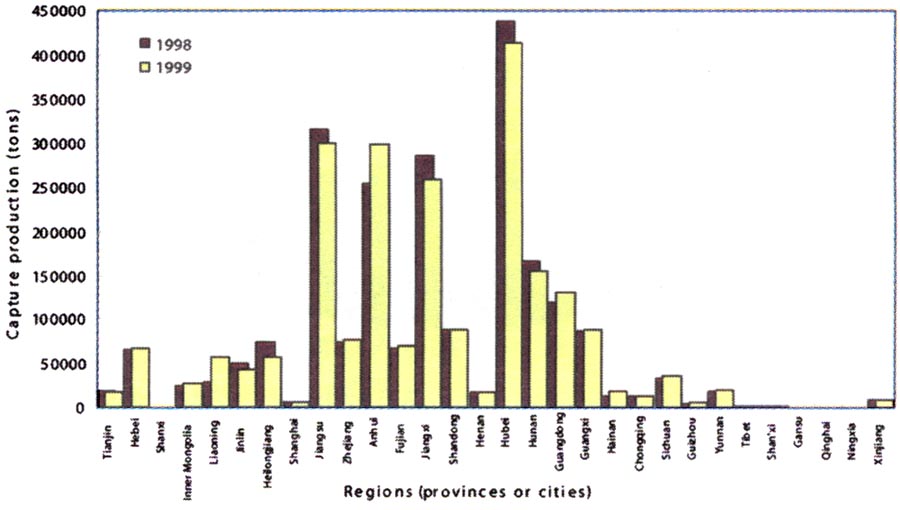

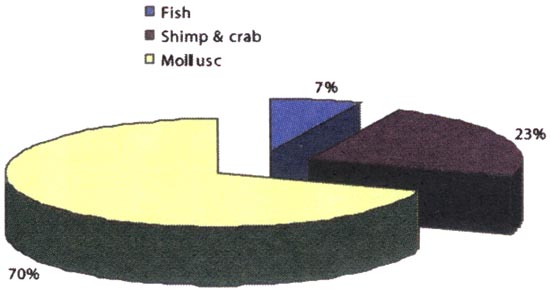

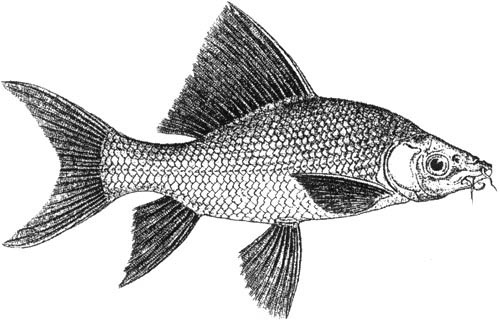

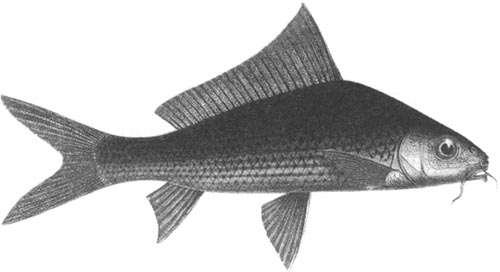

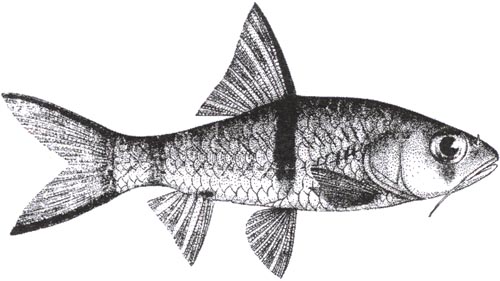

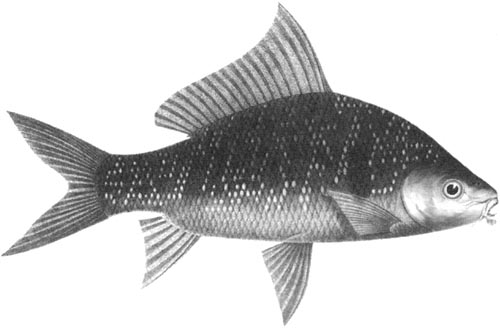

China has a history of more than 3000 years of inland fisheries. In recent decades, the inland fishery, especially aquaculture, has been well developed. Since 1981, the production from inland aquaculture increased rapidly while the production from capture fisheries increased only slightly (Fig. 1). In 1999, the total fishery production in China was 41 million tonnes. Of the 16.5 million tonnes from inland fisheries, 2.28 million tonnes came from the capture fishery and 14.2 from aquaculture. From the data in 1999, about 30% of inland aquaculture area was ponds, 28% paddy fields and 22% reservoirs (Fig. 2). Figure 3 shows that 92% of inland fishery production was fish with the remaining 8% consisted of shrimp, crab, molluscs and other aquatic animals. More than 78% of total inland fishery production was carps (Fig. 4) and most of these were from ponds (Fig. 5).

Most fisheries are operated as fish farms. Fish farmers rent the ponds and pay yearly rental. Licenses are given only for lake capture and reservoir capture fisheries and license fees are paid annually.

The statistical collection system[1]

China has a very powerful system of inland fishery data collection implemented at provincial and district levels. The Department of Fisheries under the Ministry of Agriculture is the top governmental administrative office and is responsible for policy development, protecting and developing fishery resources, foreign affairs related to fisheries, management of marine and inland fisheries, organisation of far-sea fisheries, conservation of water environments for fisheries, guiding the processing of aquatic products, standardizing fishery equipment, supervising the management of international fishery policies and fishery statistics. In every province, county and city there are fishery bureaus that represent the local office of the Department of Fisheries and manage fishery affairs.

Fig. 1 Annual inland fishery capture production in China

Fig. 2 Proportion of different fishery areas in inland fisheries in China

Fig. 3 Proportion of different fishery production from inland waterbodies

Fig. 4 Proportion of different fishery species in inland fisheries in China

Fig. 5 Proportion of inland fishery production from different waterbodies in China

The data collected for inland capture fisheries includes total national production, production in different provinces or cities, production from different water bodies, production of dominant species in different regions, areas of fishery water bodies in different regions and for different species, output value of different typologies, fishery effects (including boats used, labour used, people working in fisheries, etc.). Statistics are compiled at district level with information collected by staff at sub-district level. District officers report the information to county officers and then to provincial officers, who compile it and forward it to officers in the Department of Fisheries. Data are normally collected from fish farmers by local officers. For some areas where the data is difficult to collect, the local officials will estimate the production. Some scientists collect data by sampling, market investigations, licenses to fish farmers and fish catch in each boat. Scientific data are normally used for research work and not used for statistics. Due to the development of aquaculture in lakes and rivers, some data are compounded by inland capture fisheries and freshwater aquaculture. This type of report is normally given at the end of the year and the statistical data is only collected annually. There is sometimes a lack of data in different seasons or months.

Marine capture fishery and aquaculture statistics are collected through the same infrastructure. In contrast to inland capture fishery statistics, marine fisheries and aquaculture data are based on an estimation of the capture per boat times the total number of boats and on market surveys. For marine fisheries, information is also collected on numbers of fishers based on licensed gear or a count of fishers working onboard licensed vessels.

Aquaculture information includes areas of culture systems, species and marketing data. Generally, the statistical data for inland aquaculture is more accurate than the inland capture fishery data. Compared with inland fisheries, the statistics for marine capture is less accurate due to the difficulties in data collection.

The information produced

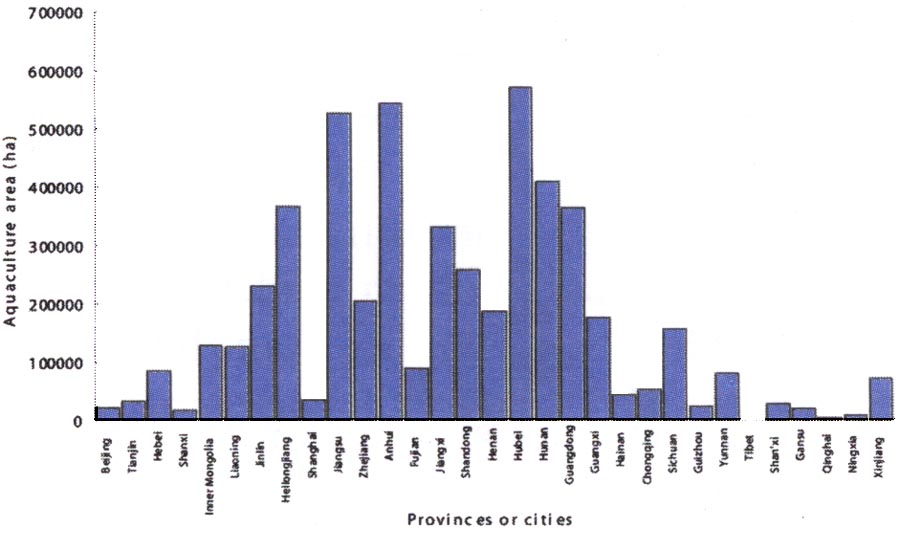

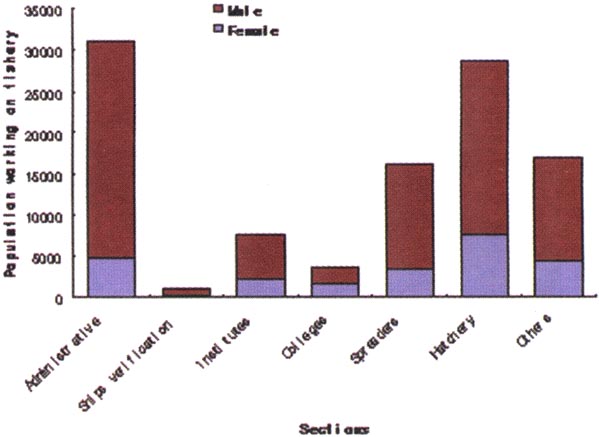

The statistical data provides detailed information on fisheries in China. Figure 6 shows the inland fishery capture production in a number of provinces and cities. The highest capture fishery is in Hubei Province followed by Jiangsu. Hubei is a province of "Thousands of Lakes" and stocking in these lakes has been very well developed. No data are available for the total capture in China at different seasons but Figure 7 shows the aquaculture areas in different regions. Most of the data include both capture and aquaculture fisheries because stocking fish in lakes is also called aquaculture in China. To the total aquaculture production, fish contributes about 70% (Fig. 8). The productivity of aquaculture in China is shown in Figure 9. Ponds have the highest productivity. Fishing effort is also reported in the types of vessels used (Fig. 10) and the number of people working for fishery management including administration, ship verification, research, hatchery etc. (Fig. 11). Women play different roles in different areas but the highest proportion of involvement is in hatchery farms and colleges.

Fig. 6 Inland capture fishery production in selected provinces and cities, 1998 and 1999

Fig. 7 Aquaculture areas

Fig. 8 Proportion of aquaculture areas for different species of inland fisheries in China

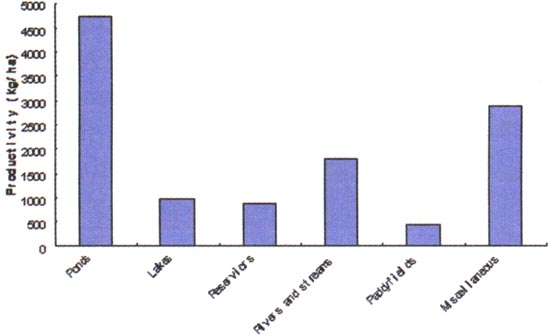

Fig. 9 General productivity of aquaculture water bodies

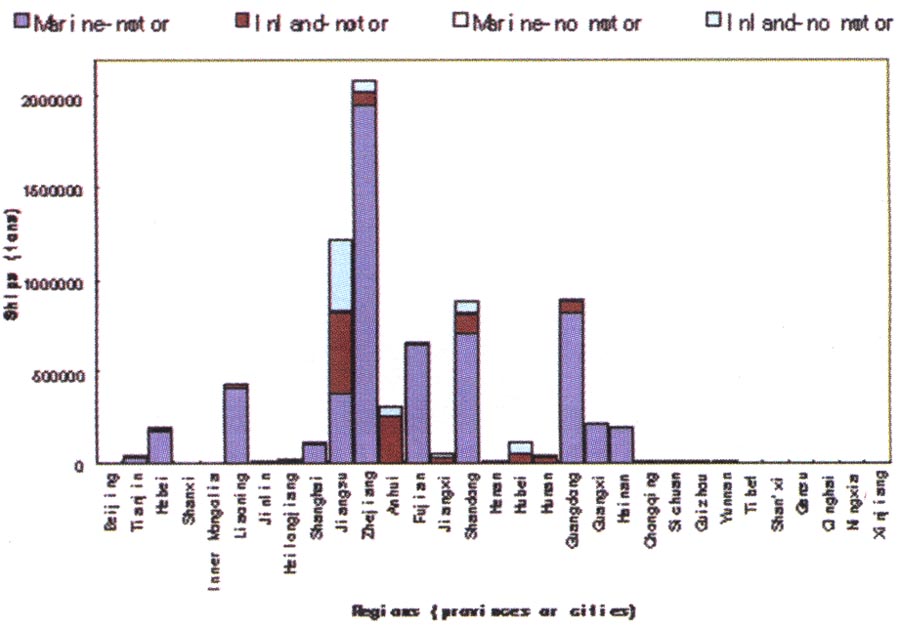

Fig. 10 Fishery ships in provinces and cities

Fig. 11 Number of people working for fisheries in different offices of fishery management

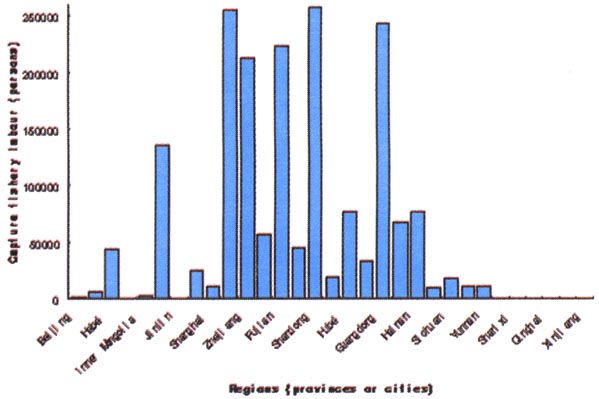

Labour in the capture fishery is shown in Figure 12, but this is the total data including marine capture fisheries. Several 'high-capture labour provinces' are seaside provinces (Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong and Guandong). Data from different provinces and cities are also published every year and similar information could be collected and the analysis for different regions could be based on these data.

Fig. 12 Capture fishery labourers in different regions (provinces or cities) in China

It is likely that the inland capture figures are affected by under-reporting but the extent is difficult to assess. For example, fish farmers normally report their production minus their own consumption. Some family fish farmers are just fishing for their own consumption. The production from other family fish farmers cannot be collected. Another problem in fisheries statistics concerns small fishes captured from natural water bodies. Due to the development of piscivorus culture, a large volume of small fishes is used as food to feed the piscivours fishes such as Chinese mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Some waste (or trash) fishes are also used as fish feed for carnivorous fish culture.

It is more difficult to capture fishery statistics in rivers. Normally, local officers report estimates. In each province, data on production of some important species are also collected, for example in Hubei province (Table 1). It can help the government and fish farmers to adjust the fishery structure, especially for aquaculture.

Table 1 Fishery production, Hubei Province, 2000

|

|

|

Production (tons) |

Proportion (%) |

|

Total production |

|

2342350 |

|

|

Silver carp and bighead carp |

Hypophtalmichthys molitrix |

878128 |

37 |

|

Grass carp |

Ctenopharyngodon idella |

496772 |

21 |

|

Common carp |

Cyprinus carpio |

163235 |

7 |

|

Black carp |

Mylopharyngodon piceus |

30976 |

1 |

|

Chinese bream |

Megalobrama amblycephala |

90242 |

4 |

|

Tilapia |

Oreochromis sp. |

5518 |

0.2 |

|

Chinese mandarin fish |

Siniperca chuatsi |

5153 |

0.2 |

|

Mitten crab |

Eriocheir sinensis |

10327 |

0.4 |

|

Ricefield eel |

Monopterus albus (Zulew) |

2456 |

0.1 |

|

Chinese longsnout catfish |

Leiocassis longirostris Günther |

50 |

0.002 |

|

Yellow catfish |

Pseudobagrus niyidus Sauvage et Dalbry |

500 |

0.02 |

|

Chinese siftshell turtle |

Trionyx sinensis |

12889 |

0.6 |

|

Freshwater shrimp |

|

64739 |

2.8 |

|

Miscellaneous |

|

599642 |

25.6 |

Perceptions of inland fisheries and objectives of the statistics

Inland fisheries play an important role in providing food and jobs. It is estimated that about 20 million people rely on fisheries in China. Due to new environmental legislation, capture fisheries have been limited and more capture fishery farmers have changed to aquaculture. A stocking fishery in lakes has also been developed in the past 20 years but is limited to definite species and densities to protect the aquatic ecosystem. As seen in Figure 1, the capture fishery is still increasing.

The data on the capture fishery and aquaculture production are used for two main purposes: to manage the fisheries in different areas to meet the market requirements and maximize the benefits for fish farmers; and to monitor the fishery resources in natural water bodies including rivers and lakes to protect the biodiversity and maintain a sustainable fishery.

Fish farmers are not always clear about the purpose of the data collection. Some farmers can get useful information from this data and plan their fishery production for the next year. They can see which species the market is lacking and how much production is required. They can even find out where they should sell their fish. For those who are managing lake fisheries, they can also find out how much fish they have captured from the lake and based on the data from the past years, they can determine the status of the natural fishery resources and change their fishing practices accordingly.

For example, in some lake fisheries, the Chinese mandarin fish is considered the main stocking species due to high production of food fish in lakes, high market value and almost no impact to the lake ecosystem at a suitable stocking density. However, high market demand has stimulated higher stocking density of mandarin fish. Using the statistical data on the fishery, they found that the production of small food fish decreased and the weight of mandarin fish at same age was lower than those in the past years. They then decided to cut down the stocking density to allow recovery of the small food fish to maintain a sustainable fishery. As a result of over-exploitation in some lakes, there are reported shortages of small fish (Song, et al., 1999). Therefore, fish farmers and the government are paying more attention to the fisheries data from the lakes so that they can make better plans for next year's capture.

The statistical data collected by the government is different from the data collected by scientists. For example, research investigations in some lakes showed that the capture fishery production was between 50-198 kg/ha in 1999 (Zhang and Li, 2002). This data is lower than that reported by the government in 1999 (around 300 kg/ha), however, the government data may have included the production of aquaculture in the lake.

Conclusions and recommendations

Generally, the statistics on inland fisheries in China is relatively complete and has been collected for many years. All this data can be used for fishery anaylsis and provides important information for the government to make plans for inland water fishery management. In recent years there has been a growing awareness and more attention to the aquatic environment and protection of water bodies and wetlands. Fish production by weight would be limited and considered not so important. Scientists have also suggested cutting down the stocking of herbivores and filtering fishes. Herbivores stocked in China normally can reproduce in nature and improper stocking would result in disappearance of large numbers of macrophytes which would lead in turn to a change from a macrophte-type lake to phytoplankton-type lake and eutrophication. Fertilising or introducing sewage to lakes for fish stocking is now not recommended and prohibited in some regions (Zhang et al., 1997). Scientists have further suggested stocking high priced species including freshwater crabs and some piscivores such as Chinese mandarin fish and snakehead to protect the ecosystem and maintain the present level of benefits for fish farmers. Net cage culture in lakes is also recommended but the proportion of cage areas or production of cage culture is limited by the government. Therefore, in the future, the inland capture fishery production will grow at a relatively constant level and may even decrease while aquaculture production will continue to increase.

Possible improvements to the present data collection system

Sampling should be done at different places for different fishery styles and also continuous sampling at definite sites. Most of the data collected at present is from the reports of different administrative levels and the reliability depends on the officials and fish farmers collecting the data. Most statistical data are collected only once a year. With the development of the fishery and the requirements of markets, the fish are sold at different seasons and the fish farmers cannot record the entire amount they sell. This will introduce high levels of error to the data. Due to the economic reforms taking place in China, more family farmers are running fish farms which also adds to the difficulties of data collection.

Statistical data should be coordinated with other data such as market data, tax data, scientific reports and banking data. On some large fish farms, data can be calibrated to the data collected from the tax office. This can reduce the tendency of some fish farmers to exaggerate data to show their 'good"achievement. Due to certain inefficiencies in the tax system, some fish farmers may report lower production figures to tax officers to reduce their taxes.

Sampling should be carried out in several places and used to calibrate the reports from the fisheries offices. The most important thing is to fund fishery scientists to undertake sampling to give more actual data at some selected places and allow calibration of the statistical data to make it more reliable.

The government should shift its emphasis from high production to more generalized economic benefits, sustainable fisheries management and environmental protection. The present emphasis on high production leads to a number of problems.

Fish farmers ignore environment protection and try to increase their fishing effort by using small eye-nets (sometimes called 'no next generation nets') and capture almost all fishes of different ages and sizes. This practice is prohibited by the government in some places. Some fish farmers fertilize or introduce sewage to increase production of some carps. This accelerates the eutrophiciation of lakes and ultimately results in many other problems including lower biodiversity and poor water quality. The high production of low-value species does not increase the overall economic benefit. The government should use economic data and environmental evaluations in place of production-only. This would help fish farmers improve lake fisheries and keep them sustainable.

Data collection should include subsistence and recreational fisheries. With improvements in the standard of living, more inland water bodies are being used as recreational fisheries. Normally these data are not included in the statistics.

In conclusion, production from the inland capture fishery in China has dropped considerably in recent years and should fall even lower due to introduced measures for the protection of inland water bodies. More fishery production will come from aquaculture. The inland capture fishery will be conjoint with stocking some high value species and more attention will be paid to aquatic environment protection. At present, more family fish farmers are forming fishery companies and most lakes and other water bodies are being operated by fishery companies. It wil be easier to collect this data and data will be more reliable and useful.

References

Song, T., Zhang, G., Chang, J., Miao and Deng, Z., 1999. Fish diversity in Honghu Lake. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 10: 86-90.

Zhang, G., Cao, W. and Chen, Y., 1997. Effects of fish stocking on lake ecosystems in China. Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica, 21: 271-280.

Zhang, T., and Li, Z., 2002. Fish and Fisheries. In: Cui and Li (Ed.), Fisheries and conservation of environment in the Yangtze lakes. AcademicPress, Beijing (in press).

"Fisheries statistics are a key component of a fisheries information system required for policy, planning, monitoring and management of fisheries."

Bounkhouang SOUVANNAPHANH

Somphanh

CHANPHENDXAY

Xaypladeth CHOULAMANY

Ministry of Agriculture and

Forestry

Lao PDR

The main objective of the Lao Government in the agriculture sector is to improve and increase the productivity of all types of agricultural commodities to achieve national food security. In Lao PDR, inland capture and culture fisheries involve a wide range of participants in the rural areas. The catch from these fisheries plays an important role in food security as it is mostly consumed by local communities and is an important source of animal protein in peoples' diets. Apart from this, inland fisheries also provide employment and livelihood opportunities. Fisheries are believed to account for about 8% of National GDP.

Lao PDR covers about 202 000 km2 of the total Mekong catchment, which accounts for about 97 % of the total area of the country. It contributes some 35% of the average annual flow of the Mekong. However, the data on living aquatic animals are limited. Generally speaking, statistical data and information on the economic significance of the fisheries sector is difficult to obtain because of the limitation of financial support, limitation of human resources and knowledge of fishery scientists in statistics. A lack of information and statistical data on inland fisheries has undermined their importance and the subsequent management of the resources. With a growing population, it is important to maintain the contributions of inland fisheries to food security and to increase production. Concerted action is required in this regard. There is a need to improve the collection of statistical data that can be interpreted in economic, scientific and ecological terms for use in planning and development. However, most fishing in Lao PDR is subsistence fishing, although there is significant commercial fishing in the Nam Ngum Reservoir.

Status of inland fisheries

Government agencies involved

In Lao PDR, the fishery statistics system is a subsystem of the agricultural system, which in turn is a part of the different statistical agencies whose primary functions are the generation, processing, analysis and dissemination of official statistics. The government agencies directly involved in the generation of fishery statistics are:

National Statistical Center under the Committee for Planning and Cooperation

Division of Statistics of the Planning Department, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF)

Department of Livestock and Fisheries (MAF)

Living Aquatic Resource Research Center of National Agriculture and Forestry Institute (MAF)

Provincial Livestock and Fishery Sections

District Livestock and Fishery Units

In the past, there were several types of information available that were relevant to the fishery at the National Statistic Center and the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry such as:

Lao Expenditure and Consumption Survey 1992-1993 (LECS I)

Collection of CPUE in Khong Island in 1993

Lao Expenditure and Consumption Survey 1997-1998 (LECS II)

The Agriculture Survey Census 1998-1999.

Meat and Fish Consumption in Xiengkhouang Province 1998

Foreign Trade Statistics

Consumer Price of Fish Index

Compilation of GDP

Baseline study in five provinces on aquaculture development projects supported by FAO (1998)

Fisheries Surveys in Luang Prabang Province 1999

Main species produced and methods used for catching

Table 1 shows the different water resource areas and their productivity in the year 2000. Previous studies of capture fisheries in southern Lao PDR were conducted in Kong falls area where there is a traditional fishery targeting migratory species. These studies produced useful data on catch effort for some fish species and can be used for managing the resource.

Table 1: Topology of national inland fisheries in 2000

|

Type of fisheries |

Water resources |

Total area (ha) |

Productivity (kg/ha/year) |

Estimate total production (tons/year) |

% of total catch |

|

Capture Fisheries |

Mekong river and 14 tributaries |

254.150 |

70 |

17.790 |

25 |

|

Reservoirs |

57.025 |

60 |

3.421 |

4 |

|

|

Sallow irrigation and small reservoirs |

34.460 |

150 |

5.169 |

7.40 |

|

|

Swamp and wetlands |

95.686 |

30 |

2.870 |

4 |

|

|

Aquaculture |

Fish ponds |

10.300 |

1.000 |

10.300 |

15 |

|

Rice-Fish |

3.050 |

150 |

475 |

0.60 |

|

|

Rain-fed rice and irrigated rice field |

477.176 |

50 |

23.850 |

34 |

|

|

Small natural pools, oxbows and irrigation weirs |

12.934 |

573 |

7.441 |

10 |

|

|

Total |

|

944.781 |

|

71.316 |

100 |

The actual record does not determine the species, but it weighed separately scale-less and scale, small and large fish for selling purposes. The main species caught are listed in Appendix 1 at the end of this paper. According to 1999 studies by the Mekong River Commission's Assessment of Mekong Fisheries Component, fishers used more than 20 different types of fishing gear and methods. The most frequently used methods were stationary, drifting gill net, long-line, cast-net, traps, hook with line, small scoop net and other traps.

Current situation of inland fisheries statistics

The production figures of capture fisheries are based on the sampling data of the yields per unit area for several types of topology. However, the information on aquaculture was obtained from data collection. Data on capture fisheries were mainly taken from fish landing sites such as Nam Ngum Reservoir and Nakasang Village on Khong Island.

Catch price at first sale varied according to the species and size of the fish and it was not recorded regularly. The average price across the country is estimated to range from 7 000 to 20 000 Kip/kg[2].

The Department of Planning (DOP) under the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) is responsible for disseminating basic statistical information on agriculture including crop production, crop area, crop yield, livestock population, animal production and fisheries. This information is prepared by technical departments and institutions such as the Department of Livestock and Fisheries (DLF), Department of Agriculture, Department of Forestry, Department of Irrigation and Living Aquatic Resource Research Center (LARReC). Technical fishery management information such as fishery production, topology of fisheries, number of fishing units, fishing gear, fish price, number of hatcheries, rate of fish consumption, rate of fry survival, fish feed production and type of fish farming is collected and compiled by the Department of Livestock and Fisheries in collaboration with LARReC, Provincial and District Livestock and Fisheries Units. This includes specific information (standard of fish stocking in pond, rate of raising in rice field, etc.), and aquatic animal health information. The trade data on fish and fish products are collated and reported by the National Statistical Center. Their data clients are decision-makers, scientists, planners and vendors.

Quality, coverage, methodological reporting

Statistical data are not readily available or, if available, are scanty and not always accurate. There are only estimated data on inland fisheries such as estimates of fish production by sampling the yield per unit of a particular type of water body then multiplying by the water area. The main reasons for the poor knowledge of these fisheries are the large number, dispersion, variety and dynamic nature of inland water bodies and the diversity of their aquatic fauna. These account for the complex and numerous fisheries giving rise to a variety of distribution and marketing systems. This makes the collection of data costly, but when weighed against the contributions of the sector in the larger socio-economic context, it may be well worth undertaking.

A household expenditure and consumption survey was taken from March 1992 to the end of February 1993 by the National Statistic Center (NST). The sample was made up of 2 940 households from 147 villages. All household expenditure and income were recorded in a diary over a one month period. At that time the amount of expenditure on fish by household was similar to the estimated official fish production figures.

The second household expenditure and consumption survey was taken from March 1997 to the end of February 1998 by NST. This time the survey included household data on fish production in terms of value, rate of consumption from their own production and fish expenditure (Table 2).

Table 2: Consumption of fish

|

Items |

Consumption value, in million kip |

|

|

1997-1998 |

1992-1993 |

|

|

Fresh fish |

30 750 |

11 040 |

|

Canned fish |

1 237 |

1 021 |

|

Frozen fish |

1 351 |

500 |

|

Dried fish |

2 183 |

1 208 |

|

Prawns, crabs, etc. |

1 853 |

162 |

|

Fermented fish |

2 934 |

1 519 |

|

Preserved fish |

755 |

|

|

Others |

4 995 |

3 626 |

|

Own produced fish |

93 410 |

26 540 |

Source: LECS I and LECS II by NSC (1993, 1998)

In 1997, a field study on meat and fish consumption was conducted by Chanphengxay in Xiengkouang Province. The sample sites were taken in two districts (Pek and Phoukout) in one month of the dry season. One was representative of urban areas while the second was representative of rural areas. The figures show that the rate of fish and aquatic animals consumed was around 4.7 kg/head/year and 4.4 kg/head/year respectively. In rural areas it was 2.5 kg/head/year for fish and 2.8 kg/head/year.

The first Lao Agricultural Census was conducted from 1998 to 1999 by NSC in cooperation with the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. It covered all 141 districts in the country. The census was undertaken in two parts: a complete enumeration of all 798 000 households to collect basic data about agriculture, and a sample survey of the households to collect more detailed information mainly on crop production and livestock, including some data on the number of families involved in fishing and aquaculture and the area of fish ponds.

Improvement of data

Because the resources required for the collection of these data have decreased, the quality, availability, reliability, accuracy and timeliness of data compiled at the national level is not satisfactory. The strengthening of the national fishery statistical systems as an integral part of a planning and decision-making process should be a major national fisheries objective in the drive towards sustainable fisheries and food security. The need to improve and strengthen data collection systems should not be limited to an individual country alone. The prospect of developing a harmonized fisheries statistics system among the countries in the region should be encouraged so that the region can share and use the data more readily to facilitate the management of their fisheries, especially in the case of shared stocks.

Since the collection and analysis of fisheries data is costly and time consuming, the needs and objectives for the statistical system must be clear and a thorough review of national statistical frameworks must be undertaken, including their linkage with priorities and objectives and the needs of respective data users. As management of the fisheries should be based on the best scientific information available, these data are critical to the sustainable management of fisheries resources.

Main issues and constraints to improving fishery information:

Lack of feedback from users

Lack of objectives and incentives for enumerators and other staff to produce quality data

Lack of awareness, especially by policy-makers, of the importance of the sector in planning and development

The collected data is not always used which further contributes to the lack of motivation among enumerators

Low levels of capacity among personnel, especially at the local level, who are mandated to collect the raw data

Fisheries statistics are not used effectively in the determination of national fisheries policy, the formulation of national management frameworks and actions or even as a basis for understanding the status and condition of fisheries resources. Since the production of effective and timely fishery statistics is a costly exercise, improvement in the use of statistics at the national level should be accorded high priority.

In the case of inland fisheries operating within an international river basin such as the Mekong Basin, these methodologies need to be harmonized with adjacent countries, and the catchment approach promoted in this regard. Once the minimum requirement for a national fishery statistical system is achieved, a gradual strengthening process can be conducted, taking into consideration the national capacity and priorities.

Conclusions and recommendations

Fisheries statistics are a key component of a fisheries information system required for policy, planning, monitoring and management of fisheries. Improvements to national and regional fisheries statistical systems including data collection, analysis and reporting are required to maximize the utility, timeliness, accuracy and reliability of fisheries statistics.

A review and reassessment of current statistics for the capture fishery is needed to obtain accurate and reliable information. The compilation and exchange of fishery statistics for the region is required to provide a wider view of the importance and status of fisheries in the economies of basin countries. Clearly, the collection and analysis of data should be standardized to facilitate this exchange. Comparable information technology and databases will assist in this regard.

Recommendations

National Level

Strengthen national fisheries statistics systems as part of a national decision framework for policy-making, planning and monitoring to achieve sustainable fisheries by:

Determining the objectives and minimum requirements of fishery statistics data and information with particular reference to national and local requirements;

Coordinating collection and use of fisheries statistics data between the national fisheries authorities and other authorities including those responsible for trade, vessel registration, freshwater aquaculture and rural development;

Building capacity at both national and local levels to collect, compile, analyze and disseminate quality statistical data and information in a timely manner as an empirical basis for formulating policies and decisions for fisheries management;

Prioritizing statistical data and information needs with particular reference to practical indicators for fishery management and the specific requirements of the region's fisheries;

Applying internationally or regionally standardized methodologies for statistical data to facilitate regional compilation and data exchange where appropriate; and

Reviewing the national fishery statistics systems to identify areas needing improvement.

Regional Level

Supporting, upgrading and expanding regional fisheries statistical systems by developing regionally compatible methodologies for national statistical data to facilitate regional fisheries assessment and data exchange; and

Promoting technical cooperation between national agencies responsible for fisheries statistics to improve national systems, including development of guidelines and handbooks.

|

Scientific Name |

Family |

Lao Name |

Water Resources |

|||||

|

M |

T |

R |

W |

R |

I |

|||

|

Akysis variegatus |

Akysidae |

Pa khao |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

Amblyrhynehiehthys truncatus |

Cyprinidae |

Pa khao tapo |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

A. bantamensis |

Babinae |

Pa khao |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

Acantopsis choirorhynchos |

Cobitinae |

Pa it |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

|

Anabas testudineus |

Anabantidae |

Pa kheng |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

Amphotistius laosensis |

Dasyatidae |

Pa phahang |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Amyda spp |

Soft-shelled turtle |

Pa phaong |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

|

Aaptosyax grypus |

Cyprinidae |

Pa sanak (adult) |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

|

Acantopsis sp |

Cobitinae |

Pa harkkoy |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

|

Arius stomi |

Artidae |

Pa khat ock soplem |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

Achiroides sp |

Soleidae |

Pa pane |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

|

Annamia normani |

Homalopteridae |

Pa thihin |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Barbichthys laevis |

Barbinae |

Pa cheork |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Bagrarius bagrarius |

Sisoridae |

Pa ke |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Botia hymenophysa |

Cobitinae |

Pa khieokai |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Bagroide macropterus |

Bagridae |

Pa kihia |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Bangana behri |

Cyprinidae |

Pa vananor |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Barbichthys nitidus |

Cvprinidae |

Pa vahangdam |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Chitala blanci |

Notopteridae |

Pa tonkay |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

C. ornata |

Notopteridae |

Pa tonqkouay |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Catlocarpio siamensis |

Cvprinidae |

Pa kaho |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

C. enoplos |

Cyprinidae |

Pa khao |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Cirrhinus jullieni |

Cvprinidae |

Pa dork ngyo |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

C. molitorella |

Cvprinidae |

Pa keng |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

C. microlepis |

Cyprinidae |

Pa phone |

× |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Cirrhinus lineatus |

Barbinae |

Pa soi |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

Clarias batrachus |

Clariidae |

Pa douk na |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

C. macrocephalus |

Clariidae |

Pa douk ouy |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

Channa marulius |

Channidae |

Pa kho na |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

C. micropettes |

Channidae |

Pa kado |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

C. orientalis |

Channidae |

Pa kouan |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

C. striata |

Channidae |

Pa ko |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

Discherodontus ashmendi |

Cyprinidae |

Pa seou |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

Dngila spilopleura |

Cyprinidae |

Pa khao |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

Euryglossa panoides |

Soleidae |

Pa pane |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Hypsibarbus lagleri |

Cyprinidae |

Pa paktongpae |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

|

H. mekongensis |

Siludae |

Pa nang hang dam |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

|

Heterobagrus bocourti |

Bagridae |

Pa kagneng |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

K. apogon |

Siluridae |

Pa nangnoy |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

K. schilbeides |

Siluridae |

Pa nangleuang |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

K. cheveyi |

Siluridae |

Pa nanghangdeng |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

Labeo erythrurus |

Barbinae |

Pa va |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

|

L. dyocheilus |

Barbinae |

Pa vanoy |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

|

Mekongina erythrospila |

Cyprinidae |

Pa sa ih |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

|

Morulius chrysophekadion |

Cyprinidae |

Pa phia |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

- |

|

M. nemurus |

Bagrinae |

Pa kot leuang |

× |

× |

× |

× |

- |

- |

|

MK |

Mekong River |

RFPF |

Rain fed paddy field |

|

TR |

Tributaries |

IW |

Irrigation weirs |

|

RL |

Reservoirs and Lakes |

X |

Available |

|

|

|

- |

Not available |

Data source: DLF, 2001

"Better resource management is urgently needed to sustain inland fisheries resources."

Oopatham PAWAPUTANON

Department of Fisheries,

Thailand

Inland fisheries is significant for Thailand in terms of providing food security and employment to a large number of fishers and rural dwellers. Inland fisheries contributes approximately 200 000 metric tonnes per year, which is less than 6% (in 1999) of the total production of fish (Table 1). Although the share from inland fisheries is not high, inland fisheries are considered the most accessible and inexpensive source of protein for most Thais, it is thus important to the socio-economic and rural development of Thailand.

Table 1: Total inland capture fisheries (1 000 ton) 1978 to 1999

|

Year |

Capture Fisheries production |

Total Area |

||

|

Total |

Marine |

Freshwater |

rai |

|

|

1978 |

|

|

102.1 |

NA |

|

1979 |

|

|

103.1 |

NA |

|

1980 |

|

|

110.4 |

NA |

|

1981 |

1989.0 |

1756.9 |

116.5 |

NA |

|

1982 |

2120.1 |

1949.7 |

87.7 |

NA |

|

1983 |

2255.4 |

2055.2 |

108.4 |

386,610 |

|

1984 |

2134.8 |

1911.5 |

114.4 |

538,421 |

|

1985 |

2225.2 |

1997.2 |

92.2 |

544,025 |

|

1986 |

2536.3 |

2309.5 |

98.4 |

546,176 |

|

1987 |

2779.1 |

2540.0 |

87.4 |

554,440 |

|

1988 |

2629.7 |

2337.2 |

81.5 |

561,669 |

|

1989 |

2740.0 |

2370.5 |

109.1 |

573,355 |

|

1990 |

2786.4 |

2362.2 |

127.2 |

2,640,326.52 |

|

1991 |

2967.7 |

2478.6 |

136.0 |

2,661,785.72 |

|

1992 |

3239.8 |

2736.4 |

132.0 |

2,731,966.78 |

|

1993 |

3385.1 |

2752.5 |

175.4 |

2,898,831.33 |

|

1994 |

3523.2 |

2804.4 |

202.6 |

2,729,470.26 |

|

1995 |

3572.6 |

2827.4 |

191.7 |

2,801,188.33 |

|

1996 |

3549.2 |

2786.1 |

208.4 |

2,696,171.56 |

|

1997 |

3384.4 |

2679.5 |

205.0 |

2,696,171.56 |

|

1998 |

3505.9 |

2709.0 |

202.3 |

NA |

|

1999 |

3625.9 |

3166.4 |

206.9 |

NA |

The development of inland fisheries in Thailand can be traced back hundreds of years, but became more systematic since the foundation of the Thailand Department of Fisheries in 1926. The Department at that time was mandated almost solely to survey and manage inland fisheries resources. Today, this task remains as one of many other missions of the Department. However, its development is hindered by many constraints. Degradation of inland habitats and the lack of up-to-date statistics are problems that need urgent attention.

State of inland fisheries in Thailand

Inland fishing in Thailand is carried out in natural and human-made freshwater bodies of various types from rivers and their tributaries to reservoirs and fishponds. The total area of inland habitats is 4.5 million hectares. This is divided into 4.1 million hectares of rivers and wetlands and another 400 000 hectares of large reservoirs. There are 47 rivers and 21 large reservoirs that contribute to the production of freshwater fish. These impoundments are situated in various parts of Thailand and play a key role in the subsistence of communities involved (Table 2). In the past, floodplains were also important inland fisheries habitats but these have almost disappeared due to the construction of dams and other infrastructure developments.

Table 2: Reservoirs and large wetland water bodies in Thailand (000 of tonnes)

|

Year |

Capture Fisheries production |

Total Area |

||

|

Total |

Marine |

Freshwater |

rai |

|

|

1978 |

|

|

102.1 |

NA |

|

1979 |

|

|

103.1 |

NA |

|

1980 |

|

|

110.4 |

NA |

|

1981 |

1989.0 |

1756.9 |

116.5 |

NA |

|

1982 |

2120.1 |

1949.7 |

87.7 |

NA |

|

1983 |

2255.4 |

2055.2 |

108.4 |

386,610 |

|

1984 |

2134.8 |

1911.5 |

114.4 |

538,421 |

|

1985 |

2225.2 |

1997.2 |

92.2 |

544,025 |

|

1986 |

2536.3 |

2309.5 |

98.4 |

546,176 |

|

1987 |

2779.1 |

2540.0 |

87.4 |

554,440 |

|

1988 |

2629.7 |

2337.2 |

81.5 |

561,669 |

|

1989 |

2740.0 |

2370.5 |

109.1 |

573,355 |

|

1990 |

2786.4 |

2362.2 |

127.2 |

2,640,326.52 |

|

1991 |

2967.7 |

2478.6 |

136.0 |

2,661,785.72 |

|

1992 |

3239.8 |

2736.4 |

132.0 |

2,731,966.78 |

|

1993 |

3385.1 |

2752.5 |

175.4 |

2,898,831.33 |

|

1994 |

3523.2 |

2804.4 |

202.6 |

2,729,470.26 |

|

1995 |

3572.6 |

2827.4 |

191.7 |

2,801,188.33 |

|

1996 |

3549.2 |

2786.1 |

208.4 |

2,696,171.56 |

|

1997 |

3384.4 |

2679.5 |

205.0 |

2,696,171.56 |

|

1998 |

3505.9 |

2709.0 |

202.3 |

NA |

|

1999 |

3625.9 |

3166.4 |

206.9 |

NA |

Fish caught from inland habitats are multi-species and vary in abundance depending on the productive status of water bodies. In general, tilapias, Thai carp, snakehead, common carp, walking catfish, climbing perch, pangasius and macrobrachium are the dominant species (Table 3). These species make up more than 90% of the total capture freshwater fish catch of approximately 200 000 tonnes.

Fishing gear used in inland fisheries is traditionally developed for small-scale fishing activities. The most widely used gear includes stationary lift net, gill net, pole and line, scoop net and cast net. These gear are quite selective and simple to use. However, the use of fishing gears in public waters has to be permitted by authorities according to the Fisheries Act 2525 (B.E.).

Practically, inland fishers can fish all year round but the amount caught may vary from season to season. Freshwater fish is abundant during the rainy season from June to September. During this period rivers, wetlands and floodplains are very productive as new water activates spawning. Yearling fish will grow to full size during this season and are the target of fishing effort. Following the rainy season (October to December) water levels in most inland habitats start leveling off. This enables fishers to easily access grown fish from the rainy season using various fishing gear. Fishing can be done all year round in reservoirs but fish are caught more readily from July to September when the water level is low.

Inland fisheries management

Better resource management is urgently needed to sustain inland fisheries resources. However, without good information and statistics for policy guidance and action planning, this cannot be achieved. Some of the tasks necessary for inland fisheries management include:

Conservation of inland fisheries resources

Rehabilitation of fisheries habitats

Upgrade the livelihoods of small-scale fishers

Strengthen fisheries control measures

Identify maximum sustainable yields of inland waters

Promote maximum use of catches to reduce waste

Assessment of inland fisheries

Thailand has continually assessed the abundance, diversity, population structure and distribution of inland fish. The methodology most used is based on Spatial and Temporal Random Design, where various replicates of sampling sites and sampling times are applied to scientifically represent habitats and seasons of interest. Practically, the assessments are carried out on at least five study sites and four sampling months (January, April, July and October). Data collected is processed according to indicators such as weight and length relationship, population dynamics, biomass and diversity for further statistical analysis using Cluster Analysis and Multidimensional Scaling.

Table 3: Fish capture in inland habitat by species 1991-1999 (Unit: 1 000 tons)

|

Species |

1991 |

1992 |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

|

Total |

136.0 |

132.0 |

175.4 |

202.6 |

191.7 |

208.4 |

205.0 |

202.3 |

206.9 |

|

Snake head |

14.4 |

14.0 |

18.6 |

21.4 |

21.8 |

25.5 |

24.1 |

16.7 |

18.0 |

|

Walking catfish |

7.0 |

6.7 |

8.1 |

7.1 |

8.1 |

5.8 |

3.4 |

10.9 |

12.1 |

|

Climbing perch |

6.0 |

5.8 |

8.1 |

6.0 |

6.7 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

4.5 |

6.3 |

|

Thai carp |

23.1 |

22.4 |

23.1 |

22.5 |

22.5 |

25.7 |

25.3 |

44.4 |

45.5 |

|

Tilapia |

42.2 |

40.9 |

53.9 |

63.4 |

55.7 |

29.2 |

28.7 |

40.2 |

49.8 |

|

Common carp |

6.8 |

6.7 |

8.7 |

8.2 |

10.1 |

7.4 |

7.4 |

11.5 |

13.7 |

|

Sepat siam |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0,2 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

03 |

1.5 |

0.5 |

|

Pangasius |

0.8 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

6.3 |

5.7 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

|

Swamp eel |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

4.4 |

5.5 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Other food fish |

35.1 |

34.1 |

52.4 |

60.0 |

51.2 |

106.7 |

108.4 |

70.2 |

59.4 |

|

Macrobracium |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

1.5 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

|

Shrimp |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

2.4 |

3.1 |

1,5 |

0.4 |

1.4 |

0.3 |

|

Others |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

Besides the sampling methods described above, there are other means of obtaining inland fisheries information. Some of these are port and market samplings to obtain landing volume, species, size and catch composition. Although this sampling method is readily used, care should be taken regarding the accuracy of data and sample size. Interviews and questionnaires are also often used for collecting data on inland fisheries. These methods are good for gathering overall views and information from various stakeholders. However, the findings may not be accurate unless the responders agree to share true data.

Constraints on inland fisheries information collection

Inland fisheries cannot be successfully managed unless information on key aspects is known. The key element that needs more investigation in Thai inland fisheries is the population structure of freshwater fish in major habitats. Such a study would reveal species composition, species distribution, maximum sustainable yield, fish production, catch and effort data and the socio-economics of communities involved. However, studies to obtain these parameters are difficult due to the following constraints:

Lack of basic up-to-date data: Information needed for inland fisheries research planning is scarce. Studies usually begin with very simple designs and are site specific and may not reflect the structure of fish communities in those particular areas.

Accuracy of data collection: The difficulty in inland fisheries data collection is due to the dispersion of data sources. If data collecting is done through interviews and port or market sampling, collectors may not get enough accurate data because data sources are numerous and disperse.

Knowledge of scientific data collection: Data collection is considered a science and gathering data has to follow scientific procedures. The lack of basic knowledge and standardization of data collecting protocols causes difficulties for inland fisheries statistics in Thailand.

Scattered information: Inland fisheries is carried out throughout the countries by mostly small-scale fishers. The information is piece-meal and scattered, making it difficult to process into an inland fisheries profile of the country as a whole.

Size of the habitat: Scientific surveys of fish populations in large ecosystems are a problem in Thailand because of the limited budgets, equipment and qualified people. These constraints need to be resolved through internal arrangements.

Solutions for inland fisheries information collection

Information is a powerful tool for planning and management of inland fisheries resources. Thai Department of Fisheries realizes the need to strengthen its framework to overcome difficulties. Some changes are currently taking place. DoF has reorganized its structure by integrating tasks that involve information into a single unit and is applying information technology to process data. DoF is also strengthening human resources to improve knowledge of scientific data collection by cooperation with intergovernmental organizations like FAO, NACA and MRC. DoF has revised the Fisheries Act to cover fisheries activities that obligate people to report data to the government.

"In the eyes of managers and policy makers, inland fisheries have never been seen as an economic activity."

THAI Thanh Duong

Fisheries Information Centre

(FICen)

Viet Nam

As a country possessing large natural water surface areas, the fisheries in Viet Nam appeared very early. According to legend, the fishery was one of the first means of subsistence of the people. The modern fishery includes three operations: marine fisheries, inland fisheries and aquaculture.

In recent years, Viet Nam's fisheries have experienced rapid development, becoming one of the major economic sectors and a key export sector making up about 7% of country's GDP. However, while the fisheries sector has developed rapidly, in particular marine fisheries and aquaculture, inland fisheries have not been given due attention even though it plays a significant role in peoples' lives.

Inland fisheries in Viet Nam include fishing for food and other purposes such as making ornamental objects, medicines and capture of seeds for aquaculture. Recently, leisure fishing has become popular around urban and tourist areas. At present, inland fisheries are declining rapidly. The capture of fish seed for aquaculture has lost its role as the only source for seed supply for aquaculture. Nevertheless, the catch from inland fisheries still plays an important role in the regular supply of animal protein for rural residents who face difficult economic conditions and have to rely on food sources they can seek themselves. In farmer households, one can find at any time certain kinds of fishing gear such as rods, crab baskets, fish traps or cages. Species usually caught include fish (carp, snakehead, catfish, eel), crustaceans (shrimp and prawns, fresh water and brackish water crabs) and mollusks (snails, clams, oysters).

However, in the eyes of managers and policy makers, inland fisheries have never been seen as an economic activity. Previously, fishers in inland waters were considered to be the poorest people with low education and no position in society. Actually, the number of inland fishers is very low and this practice is only one activity to provide food for their meals or for selling to other local people. This has some consequences. First, a source of employment to create additional income and provide food for the population has not been managed and brought into play, especially in terms of poverty alleviation. Second, non-managed fishing activities such as the use of toxic chemicals and electric shock to catch fish have resulted in the destruction and extermination of fisheries resources. Finally, without an appreciation of the role of the inland fisheries, there is little or no concern about the influence of other economic sectors on fisheries resources.

Due to the lack of concern for inland fisheries, the record of statistical data is weak. In reality, no agency is responsible for doing the statistical work. Any statistics on inland fisheries are only estimates.

Fisheries management systems

The organization chart of fisheries management in Viet Nam is rather complicated (Fig. 1). The Ministry of Fisheries (MOFI) is a government agency responsible for implementing state administration of the fisheries sector. The MOFI system includes the ministerial agency and some professional units of which three have branches in different localities, namely the Department for Fisheries Resources Conservation, the National Fisheries Inspection and Quality Assurance Agency (NAFIQACEN) and the National Fisheries Extension Centre.

The Department for Fisheries Resources Conservation has branches located in the coastal provinces and some inland provinces with large fisheries (mainly in the Mekong River Delta). NAFIQACEN has six branches set up at fisheries centres. The National Fisheries Extension Centre has a network of fisheries and agriculture extension centres in all provinces across the country.

In coastal provinces, the agency implementing the state management of fisheries is the Department of Fisheries (DOFI) which is under the management of the Provincial People's Committee. It is also subject to the professional management of MOFI (actually, there are 25 Departments of Fisheries and one Department of Fisheries-Agriculture-Forestry). Two coastal provinces have no Department of Fisheries. In other provinces, the mission of managing fisheries is carried out by the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development.

At district level, an Economics Bureau or an Agriculture-Forestry-Fisheries Bureau implements fisheries management. At commune level there is an Agriculture Board or an Agriculture-Fisheries Board.

Fisheries statistics systems

The fisheries statistics system in Viet Nam is complicated, not mentioning short-term investigations implemented by programmes and projects. At present, regular statistical data on fisheries are being collected in parallel by two systems, namely the statistical system of the Ministry of Fisheries and that of the General Statistics Office. Nevertheless, neither system has been designed to include all information fields necessary for the management of fisheries. This situation is due, on the one hand, to the complexity of the state administration apparatus as described above and on the other hand to the process of shifting the national economy from a centrally planned mechanism to a market one. These two mechanisms have different methods and requirements for economic information and statistics and have different ways of organizing the system. The qualifications and working style of officials is also different. At present, efforts are being made to strengthen the capacity of the fisheries statistics system to keep pace with countries in the region and in the world.

The main agency responsible for collecting fisheries statistics in coastal provinces is the Department of Fisheries (supervised by an Economics Bureau or an Economics & Planning Bureau). In the remaining provinces this work is done by the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. Collection of fisheries statistics by the Department of Fisheries is done according to the following methods:

Registration book and license

Reports made by district officials

Reports based on the original data of the Sub-Department for Fisheries Resources Conservation, the Centre for Fisheries Extension and the Market Management Board

Interviews and survey forms

Estimates of monthly, six-months and annual fisheries statistics, which the Department of Fisheries uses to make a report for MOFI's agency in charge of fisheries statistics