Organic agriculture in a closer sense pursues an organizational principle: to manage a mixed farm within a nearly closed system an organism alike. Since site conditions are individual properties by definition, a farm can be conceived as an individual entity. In comparison to mainstream agriculture, organic agriculture depends more on specific site conditions and is therefore forced to combine the best adapted elements to a holistic approach. If environments are dominated one-side by nature (and/or the market), farmers are forced to realize more simplified farming systems under the organic label, too. In central European conditions and humid temperate climate, the organic agriculture’s relationship with environmental quality is enhanced by a mix of crop and livestock farming that creates diversified production systems.

Normally, arable farms can be transformed into mixed farms without difficulty. These farms can fulfil the organizational principle better via integrating livestock production which enables integration of arable fodder cropping and diversified rotations. To which extent these measures are able to regulate and stabilize the whole farming system depends on the special site conditions. Often this question can only be answered by using results of long-term experiments, if available. On the other hand, in fertile soils like black earth located in dry areas of Central Europe having less than 500 mm rainfall per year, unproductive loss of water caused by inefficient use of green manure has to be avoided particularly when it is not needed for stabilization of soil-fertility. However, main forage crops, such as lucerne with its potential to increase soil fertility, will consume high amounts of water, an effect which can cause a decreased positive pre-crop effect of this potentially valuable nitrogen fixing crop. Consequently, growth of perennial lucerne must optimize the production system in a continental climate.

Table 1. Potential nutrient imbalances of different organic farm types

|

Farm Types |

||||

|

Compensation of imbalances |

Dairy farm on grassland |

Arable farm without animals |

Vegetable growing farm with glasshouse culture |

Fruit growing farm with permanent cultures |

|

Possible |

Nutrient surplus due to purchase of concentrates |

High nutrient deficiency due to export of products |

High nutrient deficiency due to export of products |

Nutrient deficiency due to export of products |

|

|

Þ Export of manure |

Þ Purchase of fertilizer/manure |

Þ Purchase of fertilizer/manure |

Þ Purchase of fertilizer/manure |

|

Restricted or Impossible |

High emission of greenhouse gases |

Low diversity of crops |

High energy input |

High energy input |

Potential imbalances of nutrients, especially nitrogen, in different farming types are listed in Table 1. Some of them can be compensated by export or purchase of manures and Fertilizers and by exchange between cooperating farms. In Northern parts of Europe but also in hilly and alpine regions, highly specialized animal farms are dominated by the site-conditions, e.g. permanent pasture that cannot be ploughed, lack of straw and high amounts of purchased nitrogen imported with feed stuffs. Permanent grass land and soil tranquillity are the main elements for stabilized agro-ecosystems, but due to frequently observed N-surplus in animal farms, definite or potential imbalances have to be equalized.

Another extreme showing similar conflicts is represented by highly specialized vegetable farms. Production of several leafy crops with short vegetation periods and fast development show high demand for nutrients. High soil fertility characterized by high soil organic matter content and high amounts of nutrients released, depends generally on purchased nutrients bound in organic manures from outside the farm and on an efficient irrigation system. To combine the one system having surplus of nutrients with the other having a lack of nutrients and a high demand for organic matter, is convincing but normally these farm types are not neighbour farms per se.

It is quite obvious that imbalances of nutrients (and energy) characterize the above- mentioned problems of farms operating under the dominating influence of the natural environment. To start with, analysis of energy and nutrient flows might open and widen our understanding for the organizational principle if farm borders were to be overcome and new system borders of cooperating farms or farm units were to be considered. In many cases it might be that farm gate balances and farm borders will not characterize and define the unit that should be under study, when keeping in mind the organizational principles for establishing a nearly closed farm organism or at least nearly closed nutrient flows.

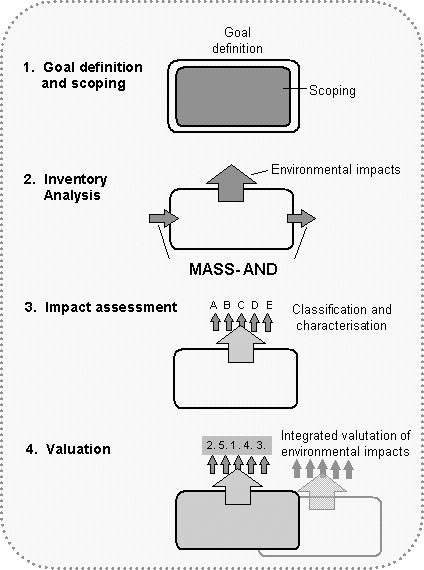

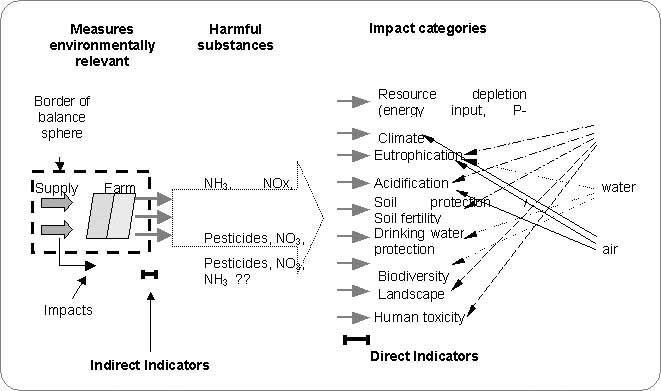

A tool to optimize organic farming might be the so called eco-balance or life cycle assessment (LCA) (Figure 1). It includes a detailed analysis of several environmental impact categories and their related system of indicators within the set frame (Figure 2).

In a first step, the ecobalance should be limited to analysis of nutrient and energy flows only. In a second step, the method can be extended by further environmental impact categories such as biodiversity, water protection, soil protection, eutrophication, acidification of soils and global warming potentials, altogether often a direct function of the energy and nutrient imbalances described.

Further imbalances oriented on impact categories that might be compensated by cooperating farms are listed in Table 2. In contrast to effects on soil protection and resource depletion which can be evaluated by the farmers themselves, other imbalances can be analysed and compensated under expert guidance only. No compensation of imbalances by farm cooperation can be achieved as regards ecotoxicity, human toxicity and animal welfare.

Combining indicators and environmental quality targets is not only an instrument for environmental assessment in general, but might also help to describe and optimize process quality and quality assessment in organic agriculture in the future. We recently finished a process-life cycle assessment (ecobalances) comparing conventional and organic agriculture in an area of 7 000 ha in Hamburg, Germany (Geier et al., 1998; Geier & Köpke, 1998). In this study organic farming did show advantages in seven out of nine impact categories. For the aims of optimizing organic farming systems by overcoming the farm borders, we also consider ecobalance a feasible impact category.

REFERENCES

GEIGER, U. and U. KÖPKE (1998): “Comparison of conventional and organic farming by process-life cycle assessment. A case study of agriculture in Hamburg”. In: Ceuterick, D. (Ed.): International Conference on Agriculture, Agro-Industry and Forestry. Proceedings 3-4 December 1998, Brussels, Belgium. 1998 PPE/R/161, 31-38 pp.

GEIGER, U., FRIEBEN, B., HAAS, G., MOLKENTHIN, V. and U. KÖPKE (1998): Ökobilanz Hamburger Landwirtschaft - Umweltrelevanz verschiedener Produktionsweisen, Handlungs-felder Hamburger Umweltpolitik. Schriftenreihe Institut für Organischen Landbau. Berlin: Verlag Dr. Köster, ISBN 3-89574-318-6.

Table 2. System of environmental indicators for farms, used in process-life cycle assessment (ecobalance)

|

Impact categories |

Compensation of imbalances by farm cooperation |

Indicators |

|

Biodiversity |

partly |

· Extent of ecological valuable

area |

|

Landscape |

partly |

· Visual effective

structures |

|

Soil protection* |

partly |

· Soil compaction |

|

Drinking water protection |

yes |

· N-leaching |

|

Eutrophication |

yes |

· N-leaching |

|

Acidification |

yes |

· NH3 losses |

|

Global warming potential |

partly |

· Emission of CO2, CH4, N2O |

|

Resource depletion* |

yes |

· Energy use |

|

Ecotoxicity** |

no |

· Emissions of pesticides and pharmaceutical effluents |

|

Human toxicity and ** working environment |

no |

· Contamination of food with

nitrate, heavy metals, pharmaceuticals and fungi |

|

Smell |

yes |

· NH3 losses |

|

Animal welfare** |

no |

· Factors of housing conditions |

|

Ozone depletion |

yes |

· Emission of N2O |

Impact categories not marked by asterisks: compensation of imbalances possible by using expert instructions

* Compensation can be performed by farmers themselves

** No compensation possible by farmer cooperation

Figure 1. Components of an ecobalance

Figure 2. Farm-borne impacts on environment

REVIEW

Since the early eighties, the University of Kassel has held a leading position with regard to academic education in organic farming. Mainly at the instigation of students of Witzenhausen and the former President of the University, Prof. Dr E.U. von Weizsäcker, the first professorship of organic farming at any university worldwide was established. Encouraged by that positive example, several student groups of other universities were also successful in installing further professorships at various universities, i.e. Wageningen (NL), Bonn, Gießen, Vienna (A) and Kiel.

The described development took place during the late 1980s and the early 1990s. Organic farming is now part of the curricula of almost all agricultural faculties to varying extents. Usually it is offered as optional, compulsive or as a facultative subject. That means students of the fifth semester and higher can go for additional education in organic farming whereas priorities are given to the subjects of conventional/integrated agriculture. The regular agriculture curriculum was scarcely changed for organic farming during the first part of the study which normally covers four semesters. The second part is dedicated to specialized fields i.e. plant production, animal production, rural economy or landscape protection. During the period of specialization, students study organic farming.

This approach is not adequate for those students who want an intensive education on organic farming. There is a high demand by students to start the studies of agriculture with actual agricultural topics, including those of organic farming and not with propaedeutics. Furthermore, there is an increasing demand for topics like theory of science and science critics.

ORGANIC FARMING AS COMPLETE STUDIES

Two years ago, the University of Kassel started a new development for the study of organic farming in order to meet requirements for the above-mentioned concepts and demands. Self-critically, it should be mentioned that the impulse and the decision for the expansion of organic farming through the entire study was only achieved by substantial external pressure of political authorities. It came from the real danger to be closed due to over-capacities in the field of academic agricultural education in Germany in general and in the State of Hessia in particular. The site of Witzenhausen was faced with two alternatives: disappearing or creating a new profile of the studies. Within critical situations the recalling of virtues is much faster; so it was in Witzenhausen, as well. Since Hardy Vogtmann was appointed to the professorship of organic farming in 1981, a noticeable development in the field of organic farming took place in the faculty:

STRUCTURE OF THE STUDIES

The study of ecological agriculture is subdivided into two periods for apprenticeships, a six semester period for the BSc. graduation and in total eight semesters for the MSc. graduation (see Figure 1). Realistically at least one semester has to be added with regard to the completion of the diploma theses, which is in total two if a student is passing both graduations. Students have to pass an on-farm apprenticeship (Professional Practical Training I), for at least six months, before they are accepted as students of Ecological Agriculture at the University of Kassel. During the first four semesters, courses are not only dedicated to the classical fields of natural sciences and the basics of agronomic sciences, but also to themes like systems theory and critics, concepts of land use and environmental relevance of agricultural practice.

After the fourth semester there is another practical period between the second and third year of studies (Professional Practical Training II). Contrasting to the objectives of the first practical stage, students should then come into contact with activities and organizations related to the actual agricultural practice. That can be for instance: agricultural organizations, trade of farm equipment, plant breeding companies, food processing industry, advisory services, agricultural administration or research.

The fifth and sixth semesters are focussed on specialization either into Ecological Agriculture, International Rural Development or Agro-management. Within the first topic their is a structure of course blocks, which corresponds to a consecutive sequence of all treated themes. Each semester contains two main blocks: soil and crops within the summer term, animal husbandry and socio-economy within the winter term. The conversion seminar is an essential course of the whole year, combining the knowledge of all disciplines, organized as student group work and dealing with existing farms so that a very high degree of practical relevance can be achieved. The third year has to be finished with a diploma thesis, which very often needs a further semester for completion and an oral examination. Students graduate with a BSc. which corresponds to an officially recognized degree for agrarian professions in Germany.

Recently a two semester master course for Ecological Agriculture was implemented at the Faculty of Agronomy and International Rural Development. The MSc. graduation includes the qualification for a PhD study. The courses of the two semesters are more science oriented compared to the more applied focus of the third year. Actually there are two main areas:

(1) Theory of Sustainable Land Use Systems; and

(2) Theory of Rural Areas.

From the next winter term on there will be a complementary choice for students to specialize either in Sustainable Regional Development or Landscape Ecology and Environmental Protection.

Figure 1. Graduated Degree Ecological Agriculture at the University of Kassel

NEW FORMS OF TEACHING AND LEARNING

Besides the changed programme of courses at the University of Kassel, efforts are also made to integrate new forms of teaching into the studies of Ecological Agriculture. Alternative assessments of qualifications are offered from the first semester on. Instead of written or oral tests, projects (including their report) are accepted as equivalent assessments. Tutoriats are another level for further qualification and assessment (Essential part of the SPOEL). Students have to take over the role of teachers, prepare, run and reflect a thematic unit for and with students. Further milestones for new forms of assessment can be the preparation and organization of a one week expert conference on relevant topics of ecological agriculture (1997: seeds in ecological agriculture; 1998: alternative veterinary medical methods) or of a one week excursion to foreign countries (1997: Poland; 1998: Sweden) which includes the choice for itinerary and the fund raising. Each of the mentioned new activities within the studies, are supervised by teaching staff members.

Within the master course, assessments of qualification are offered in the form of:

THEMATIC NETTING TO THE REGION AND TO LANDSCAPE ECOLOGY

Starting with the next winter term, the Faculty of Urban and Rural Development together with the Faculty of Agronomy and International Rural Development is offering two complementary fields of study in Witzenhausen for the seventh and eighth semesters which are also accessible to students of Ecological Agriculture (see Figure 2):

(1) Sustainable Regional Development; and

(2) Landscape Ecology and Environmental Protection.

There will be various options for the students to benefit from this broader field of disciplines. The BSc. graduates can either go for an exclusive specialization in one of the new topics or they can integrate parts of the new studies into their own master course of Ecological Agriculture.

Figure 2. Topic options for the MSc programme in Ecological Agriculture in Witzenhausen

PROSPECTIVES

The conversion of the Faculty of Agronomy and International Rural Development started one and a half years ago. It surely needs more time for the achievement of optimal shape. Essential points of critics are for example, the pronounced accentuation of the master course towards aspects of crop growing and rural development. The animal sciences and agro-economy must be given more importance in the near future.

Evaluation procedures of individual courses and the entire new master course were found to be very helpful instruments for the necessary further development. A lot of valid impulses were provided for the optimization of the new programme.

On 1 July 1998 the Faculty of Agronomy and International Rural Development was given a new big farm of approximately 300 ha close to Kassel. The latter can become a very good example for vital interdisciplinary approaches between the studies of Ecological Agriculture, Sustainable Rural Development and Landscape Ecology. The Hessian State Domain Frankenhausen will be converted to a Centre of Instruction, Research and Transfer of Ecological Agriculture and Sustainable Rural Development.

The project Sustainable Land Use and Regional Development has now been running for two years and is planned for a total of five years. We are looking forward to the success of evaluation by the Ministry of Art and Science after a further three years. At least there is a high attraction for students and they choose the additional programmes offered in Witzenhausen.

For a period of four years, the State and Federal Government provided financial support for a Model Design Ecological Agriculture, the main points of which were evaluations of the:

Last, but not least, on-going European activities should be mentioned. Under the ERASMUS programme seven European universities, Kassel as the German member of the group, elaborated a one year curriculum for Ecological Agriculture at the BSc. level, precisely emphasizing the third year of the study. This corresponds very well to the year of specialization in Witzenhausen. Whereas the German language centre could continue the general studies, the English language centres, Aberystwyth (winter term) and Kopenhagen (summer term), implemented new courses and degrees for that European collaboration.