Mustafizur Rahman, Joint Secretary (Dev.),

Ministry of LGRD, Bangladesh

Bimal Kumar Kundu, Director, BARD,

Bangladesh

The evolution of local government functions

The origin of the institution of local government in its present form in Bangladesh can be traced to the period of British rule in the subcontinent. Local government institutions were initially developed to maintain law and order in the rural areas. By the time of independence and partition of India in 1947, both tiers of local government-the Union and District Boards-had become fully elective. Several Union Board chairmen had been elected to the District Boards, some even to the Bengal Legislature showing how local government institutions could play an important role in training peoples’ representatives for higher political responsibilities.

Rural local government in Bangladesh has the following tiers

- Zila Parishad (district council) at the apex.

- Upazila Parishad (Sub district council) at the intermediate level).

- Union Parishad (union council) at the lowest level Each union is divided into wards and each ward is composed of villages.

In the past, the union parishad had about 37 compulsory functions and a similar number of optional functions but without sufficient autonomy to plan and implement projects. It was not considered necessary to give sufficient funds to local bodies because development projects were mainly prepared by the central government and union parishads were responsible mainly for helping implement the centrally prepared projects in their areas.

Even under the upazila system when, for the first time, responsibility for preparing five-year plans for each upazila was given to the sub-district councils, the plans had to be approved by the central government. There were also restrictions on the parishads’ use of funds provided by the central government. Moreover, the central government had always retained control over local government representatives through the Ministry of Local Government which could dismiss local government representatives on a number of grounds. There was, therefore, a need for clearly defining the powers of local government institutions for the preparation of development plans and utilizing government funds.

Constitutional and legal basis of local government in Bangladesh

The 1972 Constitution provided the legal basis and powers of local government bodies. According to Article 59 of the Constitution

(1) Local government in every administrative unit of the Republic shall be entrusted to bodies composed of persons elected in accordance with law.

(2) Every body such as, is referred to in clause (1) shall, subject to this Constitution and any other law, perform within the appropriateadministrative unit, such functions as shall be prescribed by Act of Parliament, which may include functions relating to -

(a) administration and the work of public officers;

(b) the maintenance of public order; and

(c) the preparation and implementation of plans relating to public services and economic development.

Representation of women in local bodies

Article 28(2) of the Constitution of Bangladesh gives women "equal rights with men in all spheres of the State and public life" and Clause 29(1) states: "There shall be equality of opportunity of office in the service of the Republic."

Constraints to local level resource mobilization

The actual demand for physical and social infrastructure at the local level (union, thana and district) far exceeds the availability of financial resources from local tax and non-tax income as well as the annual grants from the government. A renewed local level resource mobilization strategy, therefore, requires a two-pronged approach that

1. recasts sources of tax and non-tax revenue for different strata of local government, and

2. redefines the basis for government block grants and other development funds to local governments.

A revised scheme for improving the revenue income of the union parishad could include the following in the five main revenue categories:

TAXES

- Chowkidari tax and tax on households.

- Share of land transfer tax.

- Entertainment tax on theatres, exhibitions, etc

FEES

- Fees for providing certificates and other services.

- License fees on professions/trade.

- Fees for registration of marriage/divorce.

- Fees from NGOs seeking union parishad services or assistance in project implementation.

PROPERTY INCOME

- Income from hats/bazaars.

- A 75 percent-share of income from ponds of less than 3 acres, the rest going to the centre.

MISCELLANEOUS

- Share of income from sairat mahals (Water, Sand, and Stones).

Constraints to social mobilization and poverty alleviation through decentralization

Democratize decentralization supported by social mobilization is a powerful tool for poverty alleviation. However, it faces the following constraints in Bangladesh:

1. Decentralization is generally seen as a threat by politicians.

2. Local government institutions lack the necessary financial and human resources.

3. Local-level management capacities are inadequate.

4. Gaps between resource needs and availability.

5. There is a need for public-private partnership covering gaps in projects and activities; a legal framework for public-private partnership is needed.

6. Upazila parishads have a well-defined delivery system, but lack of resources and management skills makes it ineffective.

7. The union parishad as the lowest tier of rural local government needs an improved service delivery mechanism.

The following recommendations can be made to address these constraints:

- Need for national consensus on decentralization goals, objectives, tools, resources, legislation and capacity-building at all levels.

- Support decentralization with participatory monitoring and enabling policies.

- Capacity-building of national and local institutions.

- Promote good and accountable governance. (Participatory planning/social audit)

Role of local governments in poverty reduction in rural areas

1. Promotion of rural income and livelihood opportunities

The main avenue for income and livelihood generation is through local infrastructure development which provides seasonal wage employment. The Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) under the Local Government Division of the Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives, is responsible for the following infrastructure development activities:

a) construction of rural and feeder roads;

b) construction of bridges and culverts;

c) development of growth centres and rural markets;

d) small-scale water resource schemes;

e) tree plantation on road slopes and embankments;

f) routine maintenance of roads;

g) construction of school and office buildings, residential quarters and cyclone shelters.

In implementing these tasks, the LGED

- directly involves landless groups in infrastructure development works;

- eliminates intermediaries such as contractors;

- ensures fair wages to the landless.

The infrastructure development projects and activities of the LGED help create both short-term (seasonal) employment opportunities for the rural poor through construction work and regular employment through maintenance activities.

2. Improving access of rural poor to productive resources and building capacities for sustainable local resources management

The LGED has carried out a number of donor development projects with the participation of local people in the planning, implementation, operation and maintenance of the schemes. Emphasis is given to women’s participation at all levels and in all stages of the activities.

3. Empowering women, indigenous people, the disabled and other vulnerable rural poor

Local government institutions are responsible for implementing a variety of central government programmes and projects such as:

(a) community-based services for poor women and children, disabled and indigenous people, aged, other marginal most vulnerable rural poor;

(b) agro-based rural development programme for women;

(c) self-reliance programme for rural women;

(d) vocational training of women for population activities;

(e) day care services for children of working women;

(f) technologies for rural employment with special reference to women;

(g) rural women employment creation project;

(h) integrated programme for women’s participation in income generation activities and legal assistance.

The main thrust of all these projects is to integrate women in the development process through socio-economic activities to increase productivity and raise their living standards.

Proposed steps to strengthen the capacity of local governments

1. Strengthen legislation on decentralization to ensure better participation of women and disadvantaged groups.

2. Government should encourage local government institutions to develop partnerships and networks among themselves.

3. A Local Government Commission may be set up to safeguard the functions of local government and to monitor their performance.

Serajganj local government development project

The project, funded by UN agencies and bilateral donors, aims to promote increased participation of local people in local development issues; enhance the technical and managerial capacity of the union parishad leadership and foster transparency and accountability in local governance. The objectives of the five-year project started in July 1999, include the provision of infrastructure and socio-economic services to alleviate poverty and help build the capacity of elected local government institutions in Serajganj District which has 2.5 million people living in nine flood-prone upazilas and 81 unions.

Major project inputs

1. Training of union parishad members on their roles and responsibilities and on technical matters.

2. Provision of support to the union parishads in revenue-generating activities.

3. Provision of block grants to the local bodies to undertake small infrastructure construction work that encourages participation of local people and promotes socio-economic development.

4. Training and social mobilization to enhance gender equality.

5. Support to develop monitoring system of the Local Government Division.

Expected outputs

1. Increased people’s participation and interest in local governance.

2. Change in the perceptions of the intended role of the union parishad chair and members; also change people’s perception about alternative ways of getting things done.

3. Poverty alleviation.

4. A gender sensitive governance system.

5. Improved monitoring and information by the Local Government Division.

Findings:

1. Local governance improved through ‘extra’ responsibility/authority and improved capacity imparted to union parishad members by the project.

2. Increased women’s awareness through their participation in project activities is likely to have the most enduring effect.

3. A cohesive project team with NGO and government experiences is a very strong aspect of the project.

The achievements of the project are largely dependent on the cooperation of local district and upazila administrations - which has so far remained positive but informal. Formalization of the relationship might be necessary for the future.

S K Singh, Head, Centre for Panchayati Raj, National Institute of Rural Development, India

The 73rd Amendment to the Constitution of India in 1992 mandated the establishment of a three-tier system of elected panchayats (councils) with the Gram (village) Panchayat at the lowest level, Panchayat Samitis at intermediate block level and Zilla Parishad at the apex district level. The panchayats are responsible for planning and implementing economic development and social justice schemes including those in relation to matters listed by the 73rd Amendment Act in its 11th Schedule. All states have enacted new laws or modified existing legislation in conformity with the 73rd Amendment. About 250 000 Gram Panchayats, 6 500 Panchayat Samitis and 500 Zilla Parishads have been duly elected.

Salient features of the 73rd Constitution Amendment

Continuity: The panchayat is elected for a five-year-term. Fresh elections must be held before the expiry of the term or within six months of dissolution of the body.

Gram Sabha: All registered voters in a village within the area of the Gram Panchayat, form the Gram Sabha which is a grassroots forum for discussing local needs and reviewing the working of the elected Gram Panchayat.

Reservation of seats: Besides reservation of seats for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) on the basis of proportional representation, one-third of panchayat seats are set aside for women, including SC/ST. The offices of panchayat chairpersons are also similarly reserved for SC/ST and women.

Financial resources: An independent Finance Commission at the state level is to review and make recommendations once every five years for a sound financial base for the panchayats.

Operational constraints

There are many impediments affecting the functioning of the panchayats in several States with regard to structure, electoral process, rotation of reserved seats, devolution of powers, functions, control over local bodies and financial dependence.

Gram Sabha

Although meant to be a pivot of Panchayati Raj, the Gram Sabha has been sidelined in many cases. For participation in the Gram Sabha to be meaningful, it should meet periodically and not be too large a gathering. The 73rd Constitution Amendment does not make an explicit provision for this. Moreover, if a village panchayat covers more than one village, people from other villages either do not attend the Gram Sabha meeting or are reluctant to articulate their needs. Unless each village has a Gram Sabha of its own, the purpose of accountability may not be served, especially when the village panchayat has a large population.

Structure

While the panchayat at the district level is co-terminus with the administrative district, the jurisdiction of panchayats at village and intermediate level has not been specified and has to be notified by the state. Determining an adequate area for a unit of administration is quite complex due to unevenness in terms of economic resources, communication facilities, population density, level of social integration, civic commitments, etc.

Reservation of seats

This has resulted in administrative and practical problems in some states with instances of the governing party not having even a single elected representative from the SC/ST or women category, when the chairperson’s post was reserved for that category.

The rotation of reserved seats both SC/ST and for women among different constituencies in a panchayat has also posed practical difficulties. In other words, such rotation should take place at the end of every five years. If so, no SC/ST or women member will get the opportunity of occupying the same seat for a second term once the reservation is removed.

Financial autonomy

State legislatures have to enact laws to authorize panchayats to levy and collect taxes, duties, fees etc. (to raise resources), but these powers are vested with the Gram Panchayat in all states whereas other tiers have very limited financial powers.

A large-scale study conducted by the National Institute of Rural Development on functional and financial devolution to Panchayati Raj institutions in 20 states of India found a lack of commendable performance by the Panchayats in internal revenue mobilization. The majority of taxes assigned, particularly to the village panchayas, are not buoyant. In most states, except perhaps the tax on buildings and lands, several other taxes are unutilized because these are either economically less productive or politically less-feasible or cumbersome to administer.

The Panchayati Raj institutions also do not seem to have taken any initiative for resource mobilisation from existing revenue sources, for which they alone cannot be held responsible. Indian rural local governments are handicapped by the excessive control by state governments of their financial matters.

Relationship with bureaucracy

A review of the provisions in the states’ laws on panchayats reveals continuing strong bureaucratic control over the village councils. Even where direct bureaucratic control is not visible, the panchayats are placed in such a position that they need bureaucratic approvals. A pertinent question arises whether the 73rd Constitution Amendment Act should have added a fourth ‘Local List’ defining Panchayati Raj powers to the Central, State and Concurrent Lists in the Constitution that demarcate Centre and State jurisdictions.

Besides bureaucratic resistance to working within the panchayat system, it is observed that politicians at state level are not positive towards panchayats.

Inadequate local leadership capability

Panchayat leaders, especially women, illiterates and dalits need capacity-building support for governance.

Positive aspects

Improved functioning of government social welfare schemes

In many places, panchayat meetings are being held regularly. Identification of beneficiaries through the Gram Sabha and Gram Panchayat is increasing. As a result, the delivery of services under government social welfare schemes such as the national old age pension, the national family benefit and national maternity benefit schemes has become more equitable.

Empowerment of women

The first election to panchayats after the 73rd Constitution Amendment brought nearly one million women into rural local self-government institutions. There is a near unanimous feeling amongst the women that they would have been unable to get into these bodies were it not for statutory representation.

Significantly, about 40 percent of the women elected to the panchayats are from the socially marginalized sections. However, the position of panchayat chairperson is generally occupied by women from the economically better off sections of rural society. Studies in the three largest states - Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan - which rank among the lowest in social and economic performance with approximately one-third of India’s rural poor, show that about 70 percent of the elected women were illiterate or could barely read or write.

|

Kamala Mahato, Bandoan, West Bengal State Kamala Mahato is the elected head of the panchayat in Bandoan, a village of tribal and non-tribal people, most of them being farm labourers. To overcome acute water scarcity in the village, Ms Mahato had 10 tubewells dug in the village. She arranged loans under a government rural livelihood programme which enabled village women to start profitable poultry, dairy and livestock enterprises. |

A sizeable proportion of the elected women had no previous political experience. The women representatives were generally supported by their families during the elections and in performing their new political roles. While women representatives from marginalized groups like the Scheduled Castes and Tribes felt they were representing group interests in the political arena, women from the better off social sections saw their election as helping to consolidate their positions.

The apprehension that because of their lack of basic education and previous political experience, the elected women would be manipulated by men has largely been disproved. Nevertheless, there have been some instances of men using the women representatives of their families as proxies, but these are more the exceptions than the rule. Indeed, the number of "no confidence" motions against elected women representatives, particularly from marginalized groups, has gone up precisely because they refused to compromise with the powerful sections of rural community.

|

Chamund Village, Haryana State No one in this village of 1 200 people now goes to the police with a complaint as all contentious issues are resolved by the Gram Panchayat Almost every child and girl in the village attends school. The Panchayat has used grants of over Rs 350 000 to build roads, a village school, dispensary, drains and other development works. |

|

Fatima Bi, Kalva Village, Andhra Pradesh State An ordinary housewife who could not read or write, Fatima Bi, elected Gram Panchayat head to a seat reserved for women in this village, has won the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Race Against Poverty Award from the Asia-Pacific region for her remarkable work as village council leader. Inspired in her new role by the angry, social justice-seeking heroine in a highly popular Andhra film, Ms Fatima began organizing women for developing the village. Kalva soon had a metal road, a new school building and check dams. She initiated a Rs 200 000 scheme to dig a five kilometer irrigation canal and clear about 200 hectares of fallow land for paddy cultivation. On Ms Fatima’s encouragement, the women began saving a small amount of money every month and within a year, 40 thrift groups with 300 women members had saved Rs 200 000. Impressed by this, the UNDP granted Rs 1.2 million as an interest-free loan to the Village Development Organization in Kalva. Managed by a committee of representatives of women’s self-help groups, the village organization has Rs 2.0 million and loans granted by it have helped many families to start small rural enterprises. The enterprising women of Kalva have now started helping neighbouring villages with loans. Once poor and backward, Kalva now stands out as a well-to-do village with happy faces all around and modern amenities in almost all houses. |

Many male administrators acknowledge that tremendous social energy has been released with the political participation of rural women who prefer to take up community issues rather than problems affecting a few individuals. Significantly, cases of corruption reported have become rare. The resulting awareness has generated a growing desire for education among rural women, particularly for girls so that next generation panchayat leaders are better equipped for their responsibilities.

The entry of women in public life has long-term implications for gender equity. Some change in the role of men within the rural family has been observed when women go to attend panchayat meetings. While the presence of women in Panchayati Raj institutions is still to make a dent in the rural power structure, elected women are engaged in power struggles once dominated by men.

|

Shakila, Kerala State A Scheduled Caste woman in a low-income village household in Kerala State, Shakila stayed at home after passing her pre-degree examination. On the urging of a friend, she joined a women’s savings and self-help group. Here Shakila met Leela who persuaded her to contest the election for the president of the village panchayat as the seat was reserved for Scheduled Castes. Initially, Shakila’s father vehemently objected to this, but eventually yielded to pressure from the village women to let his daughter contest. Shakila also got support from a political party and won the election along with Leela. As panchayat head, Shakila took some remarkable initiatives. She began meeting several women AIDS patients in the village who were ostracized by the community and even their own families. She also supported the children of AIDS patients. Her example was followed by many social workers and slowly these children were accepted by the community. Shakila organized AIDS awareness camps for the village. However, Shakila had to face opposition in her work from her father and brothers who did not approve of her irregular work hours and travel to distant places. She faced sexual harassment from her male colleagues who even began spreading rumours about her personal life. The support of the women panchayat members helped her a lot, but Leela has lost all confidence and will not contest panchayat elections again. |

Capacity building

The National Institute of Rural Development (NIRD) has developed a training needs assessment and training design for capacity-building of Panchayati Raj functionaries, both elected and officials who need technical, managerial, administrative and human/behavioural capabilities. The first involves basic technical knowledge of different subjects such as laws relating to panchayats and resource management. Managerial and administrative capabilities include mobilization of resources, coordination, monitoring and supervision. They also need behavioural capabilities to deal with officials and villagers, generate team spirit and resolve conflicts.

The training needs will vary from state to state and must be assessed at state and district levels. However, the following core issues are common.

Understanding that panchayats are local self-government institutions and not arms for implementing state government work.

Envisaging the primary task of Panchayati Raj institutions as planning and implementing schemes for economic development and social justice.

Recognizing the village community’s right to participate in panchayat decisions.

Need for establishing vertical linkages between different panchayat tiers.

Right of panchayats to link activities of different sectoral departments.

Target group

The training target group comprises an estimated 2.7 million elected panchayat representatives and 927 500 officials assigned or closely connected with the Panchayati Raj institutions.

Training target group

|

Level |

Elected members |

Officials |

Total |

|

District Level |

13 484 |

27 500 |

40 984 |

|

Block Level |

128 648 |

150 000 |

278 648 |

|

Village Level |

2 580 286 |

750 000 |

3 330 286 |

|

Total |

2 722 418 |

927 500 |

3 649 918 |

It is also proposed to train 100 Master Trainers from all over the country, who in turn will form teams to train about 2 500 other trainers across the country with an average of five trainers for each district.

References

Charvak. 2000. From decentralization of planning to people’s planning: experiences of the Indian States of West Bengal and Kerala, Discussion paper No. 21, Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development.

FAO. 2003. A handbook for trainers on participatory local development. Bangkok, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific.

GOI. 2002. Review of the working of the constitutional provisions for decentralization (Panchayats), A consultation paper. National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution, New Delhi, Government of India.

HDRC. 2003. Decentralization in India, challenges and opportunities. (Discussion paper. Series - 1). Human Development Resource Centre, UN Development Programme (UNDP), New Delhi.

NIRD. 2002. India Panchayati Raj Report, 2001, Vol. I. Hyderabad, India. National Institute of Rural Development.

NIRD. 2002. National Action Plan for training of elected members and functionaries of Panchayati Raj institutions. Hyderabad, India. National Institute of Rural Development.

NIRD. 2003. Select readings on decentralization - exposure visit overseas on decentralized governance. Hyderabad, India. National Institute of Rural Development (Unpublished).

Richard C. Crook & Allan Sturla Sverrisson. 1999. To what extent can decentralized forms of government enhance the development of pro-poor policies and improve poverty alleviation outcomes?

Santosh Mehrotra. 2001. Democracy, decentralization and access to basic services: an elaboration on Sen’s capability approach.

Santosh Mehrotra. 2002. Basic social Services for all? Ensuring accountability through deep democratic decentralization, Human Development Report.

S. Radha, et.al. 2002. Women in local bodies. Discussion paper No. 40, Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development.

Vasanthi Raman. 2000. Globalization, sustainable development and local self-government challenges of the 21st Century: The Indian experience. New Delhi, Centre for Women’s Development Studies.

M. Thaha, Head, Centre for Micro Planning, National Institute of Rural Development, India

India’s southwestern Kerala State is a good model of decentralization of state functions, and participatory planning and decision-making at the grassroots level.

Devolution of powers

Kerala transferred most development functions to local governments in 1995. Among others:

- local governments supervise all health institutions except medical colleges;

- high schools in rural areas have been transferred to the district panchayats and primary/secondary schools placed under village panchayats;

- all centrally sponsored anti-poverty programmes are planned and implemented by Panchayati Raj institutions;

- except statutory functions relating to juvenile justice, all social welfare functions are with local governments;

- panchayats have a key role in the development of agriculture and allied sectors, rural off-farm and non-farm jobs/enterprises and rural infrastructure.

Fiscal decentralization

Of all states in India, Kerala has seen the highest devolution of finances to local governments, with Rs 14 381 million or 37.72 percent of the State Budget transferred during 2002-03. About 90 percent of Plan funds are given in a practically untied form to local governments to prepare and implement their own schemes. At least 40 percent of this is to be invested in productive sectors, 10 percent is earmarked for gender-sensitive schemes and not more than 30 per cent to be used for road construction and maintenance.

People's campaign for planning in Kerala

The People’s Campaign was a historical event in the development of the decentralization and planning process in the state. Its main objective was to enable Panchayati Raj institutions to prepare and prioritize a shelf of integrated schemes in a scientific and participatory manner for incorporation in the State’s Ninth Five-Year Plan. The campaign was divided into phases, each beginning with the training of voluntary workers, officials and people’s representatives at different levels.

The first step in the planning process was to conduct gram sabha meetings to identify and prioritize village-level development issues. Discussions were organized in 12 development sectors and facilitated by trained resource persons.

The second step was preparation of the gram panchayat development report by 12 committees set up by the village panchayat, each committee dealing with one development sector. The report for each sector was then discussed during a seminar at the gram panchayat level. Based on the discussions, 12 task forces of experts, officials and voluntary workers were set up to review programmes in each sector. The proposals made by the task forces were then prioritized and formulated into projects, which were classified according to the implementing agency at panchayat, cooperative, state government or private individuals’ level.

Capacity building

The experience of the People's Campaign has underlined the vital importance of capacity building for the success of participatory local planning.

1. In order to provide the knowledge and expertise required for participatory local planning, resource persons were identified whose services were provided on a voluntary basis. There were 660 key resource persons to be trained who, in turn, had to train 11 808 district resource persons. The key resource and district resource persons together trained about 100 000 local resource persons.

2. The participants for the capacity-building training programmes included elected members, officials, resource persons and non-official experts. Besides 14 173 elected representatives, there were 20 000 officials working directly under local bodies and 40 000 sectoral officers who were to be transferred to the local bodies. There was an urgent need to re-orient these officials to shoulder the responsibility of local-level planning within a decentralized democratic set-up.

Phases of capacity building

The training was conducted in seven rounds corresponding to each phase of the planning exercise:

Round 1 organization of gram sabhas

Round 2 preparation of development reports

Round 3 drawing up projects

Round 4 drafting plan document

Round 5 integration of local plans/drafting higher tier plans

Round 6 plan and project appraisal

Round 7 implementation rules and procedures

Methodology

The training programmes were organised at state, district, block, panchayat/local level with different categories of participants. At the state and district levels, the training was for two to five days while at the block and panchayat level, it was for one or two days.

The method followed was lecture-cum-discussion sessions, group exercises, panel discussions, case studies and sharing of experiences by the participants. Emphasis was on self-study by participants. A hand book was prepared for every round of training with the help of experts and officials. In addition, 12 monographs on sectoral plan perspectives were prepared as a part of the second and third round. A comprehensive list and description of all current development programmes were distributed. The training material included nearly 3 000 printed pages and more than 12 hours of video programmes.

Weaknesses

There were difficulties in training task force members for the third phase in terms of conceptual clarity. Partly this was due to the difficulty of translating training concepts into the local language.

There were also difficulties relating to training for project formulation. Local bodies were involved in material production, infrastructure and services/welfare projects, but commercial ventures were rarely undertaken. Projects can also be classified as long or short term as well as on the basis of beneficiaries - whether households or larger groups. The project proposal format would therefore have to be flexible enough to accommodate all these variations. The officers who attended the training had no direct experience of project preparation. It took a month of discussion to design a project format for the campaign. Financial analysis was the weakest area in project formulation during the training. Similarly, project proposals also exaggerated the expected voluntary labour and financial or material contributions from local residents. The training focused too much on general tasks; there was not sufficient involvement of department officials and the monitoring was not adeqaute.

The large number of participants and their heterogeneous nature made it difficult to conduct the course effectively. The bureaucratic and hierarchical attitudes of the senior district officers made it difficult for the resource persons, most of whom were school teachers or lower-level government employees, to conduct the classes effectively.

The campaign also revealed the difficulty, in a mass training exercise, of maintaining even quality across simultaneous local training sessions taking place over a wide area.

Achievements

All gram panchayats have prepared development plans through people's participation and these have been integrated with block and district development plans. The plans have been implemented by the gram pancnayats with people's participation and technical supervision by block and district officers. Schemes prepared at the block and district level, have been implemented by concerned departments.

As a result, there has been a significant improvement in the provision of basic needs. During the first two annual plans (1997-98 and 1998-99). 98 494 houses were built, 240 307 sanitary latrines constructed, 50 162 wells dug, 17 489 public taps provided, 16 563 ponds cleaned and 7 947 km of roads built. There has also been considerable improvement in the management of natural resources by local governments, particularly in the productive use of water resources.

Corruption has been reduced significantly in the selection of beneficiaries for different welfare/development programmes, in awarding construction contracts and in the purchase of raw materials.

Neighbourhood groups

In order to reduce the travel time for attending a Gram Sabha, neighbourhood groups of 40 to 50 families have been set up in selected Gram Panchayats. The representatives of these groups often constitute a ward committee which acts as the executive committee of the Gram Sabha. The neighbourhood groups provide a forum for discussing the local plan, reviewing plan implementation and selecting beneficiaries. They also help settle family disputes and supervise educational programmes for children as well as health and thrift schemes.

Empowering marginalized groups

A corps of tribal social activists has been formed from among educated tribal youth. They receive a monthly stipend of Rs 1 000 and help ensure greater participation of tribal people in the local development planning process.

Networking

Although voluntary organizations working in rural areas and Panchayati Raj institutions have similar goals, in most cases they work independently of each other. During the People's Campaign for planning it was felt necessary to rope in voluntary organizations and a provision was made to set up a Voluntary Technical Corps to assist in finalization of planning proposals by the gram sabhas.

Transparency

Documents relating to beneficiary selection, minutes of meetings, reports and all documents for works taken up by local government bodies have been made available to people on demand. At public work sites, essential information concerning implementation is displayed for public scrutiny.

References:

K. R. Sastry. 2001. People’s perception of Panchayati Raj in Kerala, Hyderabad, India, National Institute of Rural Development (NIRD).

M. Thaha. 2002. Planning for Gram Panchayats - Kerala model. Hyderabad, India, NIRD.

T.M. Thomas Isaac. 2000. Local democracy and development - People’s Campaign for decentralisation planning in Kerala., New Delhi, Lefword.

V. Annamalai. 2001. Role of Panchayati Raj in natural resource management: study of two village panchayats in Tamilnadu. Hyderabad, India, NIRD.

Manoj Rai, Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA), New Dehli

The Constitution of India visualizes panchayats as institutions of self-governance. However, most financial powers and authorities are to be endowed on panchayats at the discretion of state legislatures. This paper looks at the challenges ahead after a decade of decentralization in rural India following the 73rd Constitution Amendment.

Challenges

As emphasized by the "Decentralization and Devolution Panel" of the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution, Panchayati Raj institutions are to be viewed as institutions of local self-governance and not as mere implementers of centrally determined development programmes. Bottom-up comprehensive planning is to be the basis of self-governance and Panchayati Raj institutions should not be allowed to become the third tier of development administration.

Strengthening Panchayati Raj institutions entails clarity of their roles, systems of governance, accountability and transparency, and inter-linkages. Interventions in strengthening the panchayat system should focus on building, promoting and empowering women and socially marginalized sections to assume their new responsibilities.

Government, non-governmental organizations, academic institutions and the media should work together for

awareness-building and sensitization on Panchayati Raj institutions, facilitating participation of the marginalised social sections and ensuring transparency and accountability in the functioning of rural local self-government bodies;

education of voters for free, fair, peaceful and participatory panchayat elections;

capacity building of elected representatives (specially women and Dalits) to help them discharge their roles and responsibilities in an effective way; and

knowledge building on issues related to local self-governance and citizens’ advocacy for promoting an enabling policy environment at all levels

Genuine devolution

There is a tendency among state and union governments to promote/establish parallel institutions/delivery systems for the implementation of government programmes and schemes that undermine the role of Panchayati Raj institutions. In most states, bodies like the District Rural Development Agency are still functioning independently. Sustained efforts are needed by civil society organizations, self-help groups, media and academics to exert pressure on state and union governments for effective devolution of functions and resources to enable panchyats to become institutions of genuine local self-governance.

Public education to promote people’s participation in direct democracy

The empowerment of the Gram Sabha cannot be achieved merely by enacting legislation and issuing guidelines. As noted by the October 1999 report of the subgroup of the Task Force on Panchayati Raj set up by the Ministry of Rural Development, which dealt with empowering the Gram Sabha, a sustained movement should be organized to educate the people and train elected representatives and officials to internalise the Gram Sabha’s potential as an institution of participatory democracy.

State and central governments should earmark adequate resources for such a campaign which should be linked with other public awareness campaigns such as for population control, pulse polio, safe drinking water and AIDS prevention. Civil society organizations can make people aware of Gram Sabha meetings and their agenda. They can mobilize people, especially women, dalits and tribals to participate in these meetings, put forth their demands and hold the panchayats accountable for local development.

|

Pre-election voters’ awareness campaign (PEVAC) and training of elected panchayat representatives The campaign was carried out by PRIA and its partners during the panchayat elections in Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Himacahal Pradesh, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh states. The main objectives of PEVAC were (i) to enhance participation in the elections, especially by women and dalits; (ii) to create an environment for free and fair elections; and (iii) to involve local civil society organizations in this. It also aimed to create a platform for further action by non-governmental groups to strengthen participatory democracy at the local level. The campaign began with planning and strategy meetings with partner organizations, with each partner taking responsibility for campaigning in a particular locality. The actual campaign started about 15 days before the election. The message was spread through simple publicity material and folk entertainment. Public address systems mounted on vehicles played audio and video cassettes on the roles and responsibilities of citizens as voters. A deliberate attempt was made to involve different types of organizations, including government departments, the State Election Commission, local administration and the media. Although PEVAC was initiated by a civil society organization, at a later stage, the campaign was owned by all- citizens, civil society groups, the media and government. Impact studies by PRIA in different states have found that PEVAC was effective in educating people about their roles and responsibilities. Voting percentages were significantly enhanced in areas where the campaign was conducted. The election process was smooth in these areas and the number of dummy candidates was drastically reduced. The awareness campaign created a vibrant network of civil society and government organizations. After the panchayat elections, the same network was used when PRIA undertook training of the elected panchayat representatives. The PEVAC network is also engaged in a campaign to mobilize and strengthen participation in Gram Sabha meetings. |

Strengthening Panchayati Raj institutions

There are about three million elected panchayat representatives at village, intermediate and district level. Of these, nearly one million are woman and more than half a million are dalits. The majority of them are illiterate and new to political life with little or no prior knowledge of the working of Panchayati Raj institutions. The rigid patriarchal structure of rural society makes it difficult for village women to contest panchayat elections and, if elected, to participate effectively in panchayat meetings. Active participation is also not easy for the socially marginalized groups.

Capacity building is a long term and gradual process and must be integrated with the functioning of the panchayats. Both government and civil society organizations are providing training for capacity building and there is need for greater collaboration between them. For example, government organizations can train district panchayat members while NGOs and other civil society groups can provide training at other levels. Government line departments should assist panchayats in the implementation of local development schemes.

The government must create space for civil society to work with Panchayati Raj institutions without affecting their legitimate position. The role of parastatals should be redefined in relation to functions transferred to panchayats and arrangements made so they can work with Panchayati Raj institutions as technical support agencies.

Mukti Prasad Kafle, Policy Specialist, Rural Access Program

The Local Self-Governance Act (LSGA) of 1999 sets out the following goals of decentralization in Nepal:

grassroots participatory planning by all including ethnic communities, indigenous people and socially and economically backward groups;

balanced distribution of the fruits of development;

strengthening governance and service delivery capacity of local bodies;

coordinated development efforts among government, donors, non-governmental organizations, civil society and private sector;

enhanced cost effectiveness and service efficiencies;

development of local leadership and accountability of local bodies to local people;

private sector participation in providing basic services for sustainable development.

The two-tier local governance system is made up of the village development committee (VDC) and the district development committee (DDC). Every VDC has nine wards, each with a five-member elected committee, including one woman member. The nearly 4 000 VDCs in the country’s 75 districts have been given the responsibility by the LSGA for implementing basic health education and sanitation programmes, running primary schools and literacy classes as well as community health centres. The local bodies carry out most of their activities through user groups, community-based organizations and community organizations.

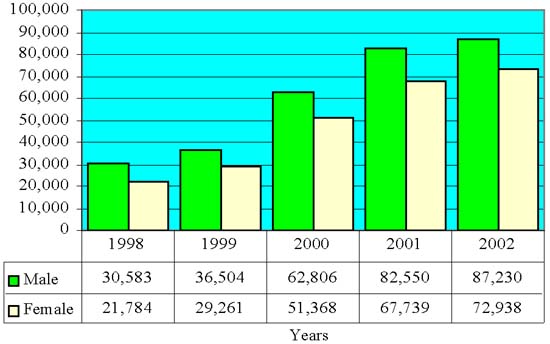

Empowerment of women and pro-poor governance

The LSGA provides for representation of women and disadvantaged groups in local governance bodies. There are about 40 000 women members of local government bodies. The number of women in leadership roles in rural community activities is increasing. Similarly, women's participation in local-level planning and decision-making is also increasing.

With the formation of female and mixed community organizations, rural women are actively participating in the planning, implementation as well as management of local development programmes and projects. Such changes have also transformed the role of rural women within the home. Once limited to household chores, they are now managing the household budget. The positive impact of women’s empowerment can also be seen in reduced social problems such as gambling and alcoholism among men as well as child marriages.

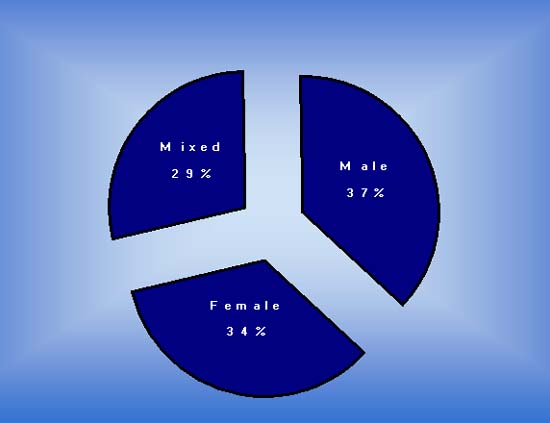

Community organizations in 30 districts

Male groups: 2 554;

Women’s groups: 2 345

Mixed

groups: 2 024.

Members in COs

Source: Annual Report 2002, LGP.

Civil society and private sector participation

Non-governmental organizations and the private sector are getting increasingly involved in the provision of basic services. The LSGA allows local bodies to work in partnership with NGOs and the private sector. All government and/or semi-government agencies engaged in development activities have involved NGOs in programme implementation.

The involvement of NGOs has given momentum to social mobilization by creating self-help organizations and community women's groups engaged in activities ranging from savings/credit to forest management.

Village development programme

The Village Development Programme (VDP) works for poverty reduction by forming community organizations (COs). The programme aims to support local communities and local governments in institutionalizing community organizations as self-governing and self-sustaining institutions to facilitate participatory development.

The social mobilization process has five stages:

- formation

- graduation

- entrepreneurial development

- implementing productive activities

- linkage with other institutions/organizations

The Local Development Fund (LDF) is the executing agency for the implementation of the VDP. The fund facilitates and helps COs to mobilize and manage resources for development activities. It organizes training programmes for capacity building of community members, and monitors, supervises and evaluates the development process. On becoming self-reliant grassroots institutions, the COs start expanding links with line agencies, banks and other institutions.

The Village Development Programme has produced the following positive impacts:

active participation of the local people in development activities in their area;

rural people are generating capital through weekly saving schemes and have initiated several income generating activities;

COs are mobilizing both internal and external resources for local development;

COs are becoming self-governing and self-reliant institutions;

increasing participation of women in planning, implementation and management of development programmes and projects;

women are actively campaigning to reduce social evils;

active participation of community members has generated a spirit of healthy competition for initiating local development activities;

encouraged rural communities to make themselves heard by authorities.

Women sway majority in their favour

The people of Kurumche village in Nibuwakharka VDC of Syangja district formed themselves into a mixed community organization. While making community-level plans for infrastructure development, they had to prioritise their needs because of resource constraints. The men wanted a farm irrigation scheme, but this was not acceptable to women who said drinking water was more important. The issue was debated for months and finally, the women’s priority was accepted. There have been similar instances of women asserting their needs in other villages, for example, opting for biogas plants above irrigation schemes and succeeding in obtaining a majority in favour of their preference.

Source: Nepal Human Development Report 2001.

Federation to be reckoned with

The Federation of Community Forest Users (FECOFUN) comprising of more than 4 500 forest user groups in 63 districts of Nepal is effectively protecting interests of the rural poor who depend on the country’s forests for food and livelihood security. Thus, when the government prepared a forest management plan for a district without consulting local government bodies or forest user groups and contracted an international agency to manage the project, FECOFUN began an awareness campaign to sensitize local communities and the government. Under pressure, the government initiated a local consultation process which led to a change in the original plan and the cancellation the contract.

In another case, the Department of Forestry and FECOFUN worked together to revise the prevailing Forestry Act. In particular, both agreed upon two particular clauses. However, these were not included in the proposal tabled in the national parliament. As a result of FECOFUN’s lobbying with lawmakers, the proposed act was sent back for revision.

Source: FECOFUN Annual Report 1999/2000, October 2000.

Awareness pays

On receiving a NRs 65 000 grant for an irrigation scheme, the members of the Langkhoriya community organization in Daraun VDC of Syangja district, committed themselves to being accountable for any misappropriation of the funds. The money was handed over to the rural technician who was sent to buy construction material, but returned empty-handed and told the villagers that the payment had to be made in advance.

However, the material did not arrive and for a while, the villagers were unable to recover the money from the technician. Reminded of their commitment when the time for repayment came a year later, the villagers mobilized all community organizations in the VDC to recover the funds, which were finally restored with 18 percent interest. A new technician was appointed who did the work in 6 months.

Source: Human Development Report, 2001.

Farmers no longer in clutches of loan sharks

Before the launch of the village development programme in Dhodhari VDC of Bardiya district, local farmers used to borrow from local moneylenders at steep rates of interest. They pledged the growing crops as collateral on the basis of the price fixed by the moneylenders, which was less than half the real price.

The VDP intervention has enabled the villagers to mobilize their savings to meet their credit needs. In addition, they can also get funds from the LDF. They no longer have to sell their crops before the harvest at a much lower price.

Source: Annual Report 2002, LGP.

Village woman becomes entrepreneur

Alaichi Karki has become a rural entrepreneur thanks to the village development programme launched in her village Sabitra in Devitar district, which led to the formation of a savings/credit group. Ms Karki bought two goats with a loan from the group. She sold them after six months to repay the loan and still had a profit of NRs 4 500. With the profit she bought more goats and they now have a market value NRs 10 000.

She could not even have thought of starting a business before the village development programme because this would have meant borrowing from the village moneylenders at a very high interest rate. She now plans to diversify her business into vegetable farming.

Source: Annual Report 2002, LGP.

Assessment of decentralization experience

Organizational structure

The number of representatives is too high compared to local government revenue. More than 90 percent of the VDCs and 25 percent of DDCs depend entirely on government grants to pay salaries of employees and elected officials. Several local government bodies are spending more on unproductive activities than on human resource development and poverty reduction.

Management

There is a high turnover of staff. The government has not yet formulated legislation for local service. As more tasks and responsibilities are devolved to local bodies, there will be a greater need for competent staff. The absence of a road map for decentralization poses a great risk of failure in the devolution process.

Efficiency

There is weak coordination at all levels, particularly between local bodies and line agencies due to a number of factors such as the central government command structure, overlapping functions between local governments and line agencies and sectoral budgetary allocation outside the local government framework. Participation of civil society, NGOs and the private sector in local government planning and service delivery is weak and uncoordinated. Civil society organizations such as users' groups and NGOs often become the tools of the local elite. However, where social mobilization in VDCs is promoted by community organizations, the programming and negotiating capacity of local societies have increased.

Access, equity and empowerment

Rural women and weaker social sections such as dalits have inadequate access to local government resources and decision-making. Only 3 percent of elected DDC members are women. The socially marginalized groups find it difficult to contest elections to local governments because of the expenses. Although included in users' groups and community organizations, they are unable to effectively articulate their needs or make known their minds.

Fiscal capacity

Fiscal decentralization has been neglected. The current share of local governments in the national budget is less than 4 percent and declining. The financial capacity of different DDCs and VDCs varies greatly due to natural endowment and geography. But there is no mechanism for reducing disparities between poorer and richer districts. Moreover, local governments lack adequate capacity for financial management.

The LSGA provides for sharing of revenue. However, the procedures for sharing the revenue generated by tourism, forests, natural resources and electricity are still to be developed. The dependency of local bodies on state grants is growing

Women’s empowerment and participation in development activities

The LSGA has reserved 20 percent seats in ward committee for women and at least one woman has to be nominated to the VDC and DDC. While this has made more than 40 000 women members of local bodies, no woman has so far been elected DDC chairperson. The legal provisions have only partially empowered the socially marginalized groups as upper castes tend to dominate public decision-making.

A 1994 study of seven forest users' groups in eastern Nepal found that only 23 women (3.5 percent) were heads of households. Most women members of the executive committee of these forest groups were nominated and unaware that they were participating as members of the executive committee.

Transparency and accountability

Transparency and accountability practices are weak at central and local levels of governance. Supervision, monitoring and evaluation are very weak at the central level. Narrow partisan and political biases prevail at the local level.

A number of local government bodies do not meet regularly. It is estimated that 75 percent of the ward committees neither hold a meeting nor inform the public how they have used the funds raised. Irregularities in audit reports are seldom addressed. Most VDC meetings are held without an agenda and influential members are able to push through their priorities. Local elites are able to dominate because elected officials often lack both the capacity and guidance to discharge their responsibilities.

The LSGA has specific provisions to ensure transparency and accountability in local governance such as a council for approving programmes/budgets, an obligatory requirement for local bodies to make programmes, budgets and decisions public, specific criteria for planning and priorities, and internal and external financial audit systems. Elected officials have to declare their personal assets within one month of taking office.

In the absence of clear provisions in the Constitution, the decentralized system of local governance is vulnerable to executive discretion and uncertainties. The Maoist insurgency also has disrupted the decentralization process with local government representatives being forced to resign and others abducted. Many VDC buildings, health posts, police posts, postal houses have been destroyed by the insurgents.

References

ADDCN. 2001. Decentralization in Nepal: prospects and challenges. Findings and recommendations of joint HMG/N (His Majesty’s Government, Nepal)- Donor Review. Lalitpur, Nepal.

ESP. 2001. Pro-poor governance assessment in Nepal, Kathmandu.

FAO. 2003. A handbook for trainers on participatory local development. Bangkok, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific.

Gurugharana, K. K. 1997. Poverty and poverty reduction agenda in Nepal. Kathmandu.

HMG/N. 1990..Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal, Kathmandu, Ministry of Law, HMG/N.

HMG/N 1993. Civil Service Act, Kathmandu, Ministry of Law, HMG/N.

HMG/N. 1994. Civil Service Regulation, Kathmandu, Ministry of Law, HMG/N.

HMG/N. 1999. LSGA, Kathmandu, Ministry of Law, HMG/N.

HMG/N. 1999. LSGR, Ministry of Law, Kathmandu, Nepal.

HMG/N. 1999. Local body financial administration regulation. Kathmandu, Ministry of Law, HMG/N.

HMG/N. 2002. The Tenth Plan (2002-2007), Kathmandu, NPC (National Planning Commission).

LDTA. 2002. Poverty reduction and decentralization: a linkage assessment report. Lalitpur, Nepal.

LGP. 2002. Annual Report, Lalitpur, Nepal.

NPC/MoLD. 2002. A national framework document for decentralized governance and capacity building. Kathmandu.

NPC/UNDP. 1991. Democracy, decentralization and development. Kathmandu.

PDDP. 2002. Annual Report (Putting People First), Bakhundol, Lalitpur, Nepal. UNDP. (2002). Nepal Human Development Report (Poverty Reduction and Governance) 2001, Lalitpur, Nepal.

Report of FAO-sponsored mission of Indian experts to Nepal to study decentralization experiences. 2002. (Unpublished)

Nayan Bahadur Khadka, Executive Director, LDTA, Kathmandu

Introduction

Systematic efforts towards decentralization in Nepal began in the 1960s with the establishment of separate district, municipality and elected village level panchayats with the authority to make policy, implement programmes and levy taxes. The 1990 Constitution stipulates as the chief responsibility of the state, the establishment of conditions suitable to the wider participation of people in the governance of the country.

However, the Village Development Committee (VDC), Municipality and District Development Committee (DDC) Acts of 1992 did not institutionalize horizontal accountability of line agencies to local government bodies. There was inadequate coordination between line agencies and local bodies in planning and implementing programmes with duplication of tasks and responsibilities. To overcome these problems, the newly elected local bodies demanded authority over line agencies.

The recommendations of the 1996 Decentralization Coordination Committee headed by the Prime Minister formed the basis of the Local Self-Governance Act (LSGA) of 1999. The LSGA is the most comprehensive piece of legislation with far reaching consequence that Nepal has ever implemented in respect of decentralization and local governance.

SWOT analysis of decentralization in Nepal

STRENGTHS

Unified Act: The LSGA integrates three local bodies (VDCs, Municipalities and DDCs).

Division of functions: The Act has attempted a division of roles and functions between central government agencies and local bodies by devolution of a wide range of sectoral functions instead of by delegation and deconcentration.

Provision of guidelines for annual planning: DDCs must receive estimates of budget ceiling and guidelines from the central government in advance for each fiscal year.

Participatory planning: The LSGA has sought to institutionalize bottom-up participatory planning. Each level of local body has to follow the bottom-up planning approach and prepare a resource map of its own area. Each level has to prepare its periodic plan on which annual plans need to be based.

Development of information management system: The Local Governance Programme (LGP) and Rural Urban Partnership Programme (RUPP) information management system has been developed in the district and municipal area which has enhanced efficiency. Twenty two districts have prepared district profiles, 22 districts have prepared analytical resource maps and 17 districts have prepared analytical poverty maps (UNDP, 2003). These have helped the DDCs in preparing more realistic, periodic as well as annual plans of their respective areas.

Fiscal provision: Local bodies can generate their own resources, obtain grants/fiscal transfers and borrow from banks. A Local Authority Fiscal Commission is working actively. Some local bodies have become financially sound (Nepal, 2004:2).Representation of women: One woman member is compulsorily nominated to each VDC and DDC council and at least one to each VDC executive committee, municipal board and DDC board. Likewise, one seat has to be filled by a woman through election in each VDC and municipal ward committee.

Voice to disadvantaged groups: Marginalized groups have representation in VDCs.

Local Service Commission: A Local Service Commission for local bodies.

Support of other agencies: District level government offices have to provide necessary support to local bodies, as and when necessary.

Provision of DIMC: Provision for a Decentralization Implementation and Monitoring Committee (DIMC) to monitor and ensure implementation of LSGA in accordance with its objectives, policies and provisions.

Mobilization of COs and NGOs: Mandatory provision for local bodies to involve local communities/beneficiaries in identifying projects/programmes, implementation and maintenance of development projects. This has occurred through self-help users’ committees, community organizations (COs), women’s groups and non-governmental organizations.

Citizen chart: Forty four districts have prepared and introduced citizen charts which will enhance public confidence in the local bodies.

Mobilization of external resources: Some local bodies have been able to mobilize external resources by directly signing MOUs with donors getting government pre-approval.

WEAKNESSES

Old mindset: Central line agencies continue to regard local bodies as subordinate agents of local development rather than autonomous units of local self-governance.

Poor linkage between municipality and DDC: No functional and institutional linkages, the only link between the two being election-related. Municipality members participate in DDC elections.

Limited role of ward committee members: Ward committees lack both financial and human resources to fulfill assigned roles and functions. Many ward committees could not meet even once.

Limited institutional capabilities: Very few local bodies have been able to satisfactorily carry out the given tasks, particularly the VDC which is the focal point for decentralization. The VDC has only a secretary and a technical assistant. Some VDCs do not even have a secretary.

Planning overlap: The planning processes of local bodies and government line agencies often overlap.

Limited revenue capacity: The LSGA authorises local bodies to impose and collect taxes, service charges and fees. However, revenue generation by local government bodies is inadequate and they depend largely on grant.

Lack of grant criteria: Grants are distributed equally to all VDCs irrespective of their size, population and development status.

Partisan politics: Executive members in almost all the local government bodies represent more than one party and partisan political interests influence the functioning of the local bodies. In some cases, conflicting interests have stalled the functioning of local bodies. Partisan political affiliations also affect the relation of local bodies with the central government if the latter is formed by a rival political party.

Status of local civil service: There has been little progress towards setting up a local development-oriented civil service accountable to local bodies as required by the LSGA.

Unsuitable nomenclature: The designation of local bodies as committees does not convey their true role as focal institutions for local self-governance. It is not easy to make people understand what these committees stand for.

Contradicting laws: Several laws are at variance with LSGA provisions, creating obstacles for local bodies in their work.

Too many units: There are too many VDCs and DDCs. The determination of territorial jurisdictions of local bodies is not scientific.

Programme priorities: Most local bodies are focusing on infrastructure development rather than income generation and poverty reduction.

Governance: Local bodies, especially VDCs have not been effective in terms of inclusion and participation at local level in governance. Utilization of financial resources is also inadequate.

Functioning of DIMC: The DIMC was set up to monitor the implementation of the LSGA. Very active in the beginning, it needs to regain the earlier momentum.

OPPORTUNITIES

Favourable international environment: Multilateral and bilateral development agencies are giving priority to decentralization issues.

Competitive political environment: Political parties and the intelligentsia are in favour of decentralization and local self-governance.

Representation in national assembly: The provision for the election of 15 local body representatives to the National Assembly enables local governments to voice their concerns/interests at apex national level.

Development of local leadership: Local bodies can be training grounds for developing political leadership.

Local civil service: The provision for a local civil service can help in attracting professionals to local bodies.

THREATS

Lack of constitutional provision: There is no constitutional provision for local self-governance, which is mandated only by the LSGA that can be changed by a simple parliamentary majority.

Political violence: The Maoist insurgency has adversely affected the functioning of local bodies.

Political culture: The centralized political culture impedes the process of decentralization.

Parliamentary constituency development fund: The constituency development fund for members of Parliament goes against the principle of local self-governance. In some districts, this fund was more than the grant to the district.

Regional administration: Regional Administration Offices functioning as deconcentrated units of the central government can conflict with and contradict the role of local bodies.

Government policy/strategy and programme

The poverty reduction strategy is based on four pillars: high and broad-based economic growth; focus on the rural economy; human resource development through effective delivery of basic social services and economic infrastructure; and inclusion of the poor and marginalized. The main strategies being adopted to achieve these objectives include:

devolution of basic service delivery function;

capacity building of local bodies;

decentralization of certain revenue functions.

Capacity-building needs of local bodies

Local bodies need capacity development in the following areas:

Strategic management.

Participatory planning and management.

Financial management.

Information management system.

Leadership development.

Organizational development.

Project monitoring and evaluation.

Orientation on LSGA and decentralization.

Gender and development.

Political awareness and leadership development for elected and nominated women representatives.

Conflict management and negotiation skills.

Office management.

Partnership building with civil society and business sector.

Facilitation skills.

The Tenth Plan set a target to train 1 200 DDC officials, 50 000 VDC officials, and 1 500 municipality officials in the first and second years after the election. In the case of the VDC, there is provision for the establishment of an information system, a computerized accounting system, social mobilization, and self-employment programmes.

The Local Development Training Academy (LDTA) was established in 1993 with the mission of enhancing managerial and administrative capabilities of local bodies. Over the years, LDTA has developed a number of training packages and trained thousands of local representatives and employees of local bodies. Donor agencies are also supporting capacity development of local bodies in Nepal in core areas.

LDTA training

|

Training package |

Recipients |

Duration |

|

Orientation on LSGA |

DDC representatives/employees/Line agency officials/Municipal representatives/employees. |

2-day |

|

DDC planning process |

DDC representatives/employees |

5-day |

|

District HRD |

DDC representatives/employees |

5-day |

|

Participatory planning process |

DDC & Municipality employees/DDC Partner NGOs |

10-day |

|

Development of district facilitators |

District people |

6-week |

|

VDC planning process |

VDC representatives/secretary |

7-day |

|

Local governance |

VDC representatives/secretary |

4-day |

|

VDC account |

VDC secretary |

7-day |

|

Political awareness and leadership development |

Elected/nominated women representatives at village level |

6-day |

|

VDC management |

VDC secretary |

5 weeks |

|

VDC planning & account management |

VDC secretary |

11-day |

Conclusion

It is often said that the LSGA has devolved powers and functions to local bodies for which they are not prepared. The first and the foremost challenge for effective local governance is enhancing the capabilities of local bodies. This requires coordinated efforts among local bodies, government, donors, NGOs and training centres.

Moreover, local body autonomy is greatly restricted by the dependence on central grants and local government institutions need technical support for mobilizing internal/own resources. It is equally important for the central bureaucracy to change its mindset and the political leadership at the central level to have trust in local bodies. Elections to local bodies could not be held due to the Maoist insurgency which has set back the process of decentralization.

References

ADDCN. 2001. Decentralisation in Nepal: Prospects and challenges. Findings and recommendations of joint HMGN-Donor Review, Lalitpur, Nepal.

HMG. 1990. The Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal. Ministry of Law and Justice, Kathmandu.

HMG. 1999. Local Self-Governance Act 1999, Ministry of Law and Justice, Kathmandu.

HMG/NPC. 2003. The Tenth Plan (Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper) 2002-2007, Kathmandu.

HMG/UNDP/et.al. 2003. Bridging phase programme. Unified report. Kathmandu.

Kafle, M. P. 2004. Capacity building for effective participatory local planning and empowerment of rural women and rural poor through decentralization.

LDTA. 2002. Poverty reduction and decentralization: a linkage assessment. Lalitpur, Nepal.

Nepal, K. R. 2004. Local Self-Governance and functioning of DDC (in Nepali).

Sant Bahadur Gurung, Vice Chairperson, National Foundation for Development of Indigenous Nationalities,Kathmandu

Mukti Rijal, Institute of Governance and Development (IGD)

Marginal groups

Nepal is a multicultural society with different ethnic groups and religions. The three broad civilization traditions are Tibeto-Burman in the northern mountains, Indo-Gangetic in the southern Terai plains and a mix of the two in the middle hills (Shrestha, 2000). A 1996 government task force on Indigenous communities of Nepal identified 61 distinct Janjatis (ethnic groups) which do not fall under the Hindu hierarchical caste structure and have their own language, religion and traditions.

Among the indigenous groups, only the Newars have an average income that is above the national poverty level. Others like the Gurungs (45 percent), Tharu (48 percent), Rai (56 percent), Magar (58 percent), Tamang (58 percent) and Limbu (71 percent) live mostly below the poverty line.

Apart from the ethnic groups, approximately 15 percent of Nepal’s 23 million people belong to the untouchable castes (Dalits). Dalit settlements have not received adequate priority from development projects. Untouchables are also under-represented in public institutions.

Rural women in Nepal have lower levels of literacy compared to men, lack property rights and assets, have limited decision-making roles, and work longer hours per day (Uprety, 2003).

It is estimated that approximately 12 percent of Nepal’s population suffers from various types of disability. The Maoist insurgency has physically disabled thousands of people and hundreds of thousands of people are internally displaced.

Constitutional protection

Article 11 (3) of the Constitution of Nepal maintains that special provision may be made by law for the protection and advancement of women, children, the aged, the physically or mentally incapacitated or those who belong to an economically, socially or educationally backward class.

The Constitution also bans untouchability. Article 11(4) prevents the state from denying access to any public place or depriving any person of the use of public utilities on the basis of his or her caste (Dhungel, Adhikari, Bhandari & Murgatroyd, 1998).

The Local Self-Governance Act, 1999 reserves 20 percent seats for women in local bodies especially at the ward committee level.

Women's participation in local government:

|

Local bodies |

Total representatives |

Women representatives |

Women’s share % |

|

Districts Councils |

10 000 |

150 |

1.5 |

|

District Development Committees |

1 117 |

75 |

6.7 |

|

Municipalities |

4 146 |

806 |

19.5 |

|

Village Development Committees |

50 857 |

3 913 |

7.7 |

|

Village Councils |

183 865 |

3 913 |

2.1 |

|

Ward Committees |

176 031 |

35 208 |

20.0 |

Source: Election Commission of Nepal, 1999

Dalits and disadvantaged groups in local government bodies