The previous chapters have demonstrated that strategies for catalyzing the formation of local institutions for collective management of natural resources must include a number of factors. In particular, they need to build local organizational capacity through using catalytic implementing agencies to facilitate group formation, elicit and manage demand for productive NRM subprojects. The implementing agencies must also provide technical assistance for design of subproject interventions, especially in a context where private contractors such as NGOs and consultancy firms are either unavailable, or lack capacity.

The financing instrument used by donor agencies must facilitate the following:

government ownership of the program;

strengthened government capacity to implement the program; and,

community authority and control over decision-making, implementation, procurement, operation and maintenance; and,

quick accrual of subproject benefits through local level approval and disbursal mechanisms.

This chapter will discuss the design of appropriate donor financing instruments that are suited for these tasks. The underlying assumption is that there should be a complimentarity between the financial facility, the capacity building function of the implementing agency, and program strategies to strengthen local organizational capacity.

In essence, there are two types of financing instruments currently available within the Bank that are sufficiently versatile for achieving the above mentioned goals: Social Funds and Demand Driven Rural Investments Funds (DRIFs). Conceptually, both instruments are very similar (Wiens and Guadagni, 1997; World Bank, 1997c). In practice, however, there is considerable variation in their design aspects.

According to a recent portfolio review of Social Fund programs (World Bank, 1997c), Social Funds are quasi-financial intermediaries that channel resources, according to predetermined eligibility criteria, to small-scale subprojects that are proposed, designed, and implemented by public or private agencies, or by the community groups themselves.[21] Unlike conventional Bank projects, individual subprojects are not determined at the time the Social Fund is established; only the criteria for subproject eligibility are laid down up-front. Social Fund agencies posses two unique features:

(i) they are vested with investment programming powers i.e. the powers to select/reject subproject proposals that they solicit from public organizations, private organizations, and/or community groups based on predetermined criteria rather than themselves identifying designing and implementing subprojects; and

(ii) they enjoy a special status in terms of their independent legal persona, control over the subproject approval process, and/or exemptions from prevailing public sector rules and regulations relating to issues such as civil service salary schedules, procurement, and/or disbursement.

Demand Driven Rural Investment Funds are similar to Social Funds, except they do not create special project units with special status but, instead, vest the investment programming functions (the power to reject/select subprojects) in existing local government institutions. Local government is responsible for soliciting and financing subproject proposals from community groups and other private and/or public organizations rather than itself identifying, designing, and implementing the subprojects (World Bank, 1997). An additional difference is that DRIFs are primarily rural focused and have been used to fund productive infrastructure investments and, to a limited extent, natural resource management activities (Wiens and Guadagni, 1997).

Local Development Funds (LDFs) as used by UNCDF, are similar to DRIFs in that they channel small-scale capital grants to lower levels of government for the financing of rural development and poverty alleviation. They are also designed to introduce or improve decentralized, participatory planning procedures and to build the capacity of local governments and other local institutions to design and manage local projects (Romeo, 1996).

The portfolio review of Social Funds (World Bank, 1997c) found some evidence that Social Funds are able to construct infrastructure at a lower cost than public agencies with cost savings reaching up to over 50 percent in specific areas. Moreover, there is some evidence that Social Funds construct infrastructure within a lesser time (30 to 70 percent less) compared with public agencies. It is these two characteristics, in particular, that make them attractive for funding community-based NRM subprojects.

As mentioned in section 0, the joint goods nature of natural resource management interventions means that conventional DRIF design, with its reliance upon local government for soliciting subproject proposal from communities, may not be the most appropriate mechanism. The complexity of eliciting demand and the requirement for specialized technical assistance is usually beyond the capacity of many local authorities. Therefore, a catalytic implementing agency is required to work directly with resource appropriators. Nevertheless, the financial instrument used by a community-based NRM program should not by-pass and ignore the presence of local government. Local authorities have a responsibility (and are ideally located), for managing the inter-community conflicts between resource appropriators that are often associated with common pool resources. Ultimately, local governments should also be empowered to develop multi-year planning capabilities for providing services and capital investments. However, before local government can assume their responsibilities in this arena, they first need to develop competence to recognize the underlying causes of resource degradation; mediate and resolve conflicts between communities; and, develop planning capabilities for the provision of public goods, infrastructure and services. DRIFs and LDFs, if properly adapted, can facilitate the evolution of local government capacity to undertake these functions (see Narayan and Ebbe, 1997 for an excellent description of the essential features for the design of Social Funds).

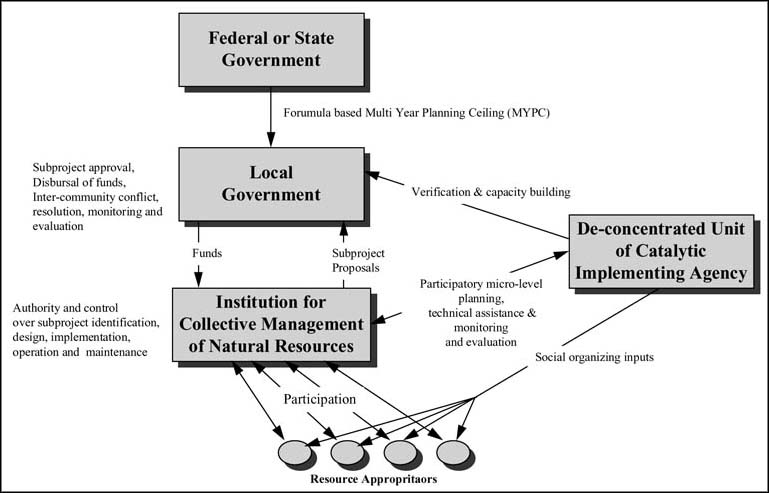

Box 10 illustrates the possible roles, responsibilities and relations between the various institutional actors in a community-based natural resource management program. In this arrangement, local government is assigned a Multi-Year Planning Ceiling (MYPC) through an intergovernmental fiscal transfer from federal or state government based on a transparent formula. [22]

Box 10: Roles and Responsibilities of Institutional actors

The MYPC is a fixed amount of resources earmarked for NRM, assigned to local government, and allocated for a given community.[23] MYPCs have been used by UNCDF as part of Local Development Funds. It was found that they can act as an incentive for community participation because of the need for collective decision-making to prioritize the use of limited funds as well as the need to complement these funds with additional local resources (Romeo, 1996). This is partially corroborated by Shah (1994) in reviewing intergovernmental fiscal relations in developing and transition economies. Shah found that increased fiscal autonomy for lower levels of government can help to mobilize more revenue from local sources and decentralized decision-making encourages local participation in development.

The implementation process is as follows. The implementing agency catalyzes the formation of a local institution of resource appropriators. It conducts a participatory micro-level planning exercise with the institutions and assists them in producing a list of prioritized subprojects. These are submitted to local government by the local institution. Local government has responsibility for reviewing and approving subproject proposals against agreed eligibility criteria. Once proposals are approved, the funds are released by local government to the institution who takes on responsibility and has authority and control over all aspects of the implementation of the subproject. The local institution has the option to contract technical assistance from private contractors such as NGOs or other actors (if they exist), in preference to the implementing agency.

In order for the above implementation and financing arrangement to be effective, the decentralized financial facility must incorporate the following essential attributes.

Democratic decentralization of government is a relatively recent phenomenon is many developing countries. There is not a tradition of political participation in countries that are experimenting with democratic decentralization. Moreover, many governments, whether centralized or decentralized, are not accountable to their constituencies (Manor, 1997). In this context, decentralizing fiscal autonomy to local government may not yield the expected benefits in terms of resource allocation efficiency and participation (Oates, 1972; Shah, 1994). The challenge in adopting a decentralized fiscal instrument is to ensure that the local government body responsible for subproject approval and fund management is accountable to the resource appropriators and is transparent in its operations.

The NRDP in Brazil has managed to establish local government bodies that are relatively democratic and representative in an environment that was characterized by high levels of rent seeking by government bureaucrats, politicians and local elites. The NRDP uses specially formulated Municipal Development Councils (MDCs) to manage a MYPC allocation; prioritize subprojects received from Community Associations; and, disburse funds to these associations for subproject implementation. The approach has been evaluated and found to be effective, accountable and transparent in regard to the management of funds allocated to the MDCs (World Bank, 1997).[24]

The MDCs are usually chaired by the Mayor of the municipality. This is not a requirement of the program, but in practice, most members of the MDC view the Mayors participation as crucial to leveraging additional municipal funds to compliment those of the NRDP. The Community Associations elect representatives to the MDC. Broader civil society representatives such as NGOs, churches, civil associations are also executive members of the MDC. Through a process of evolution, the program now insists that at least 80 percent of the voting membership of the MDC must be representatives from Community Associations and civil society. In addition, de-concentrated units of federal and state departments are also present on the MDC, but without voting rights. Finally, a representative of the implementing agency (State Technical Unit) is also a non-executive member of the MDC and ensures that the selection of subprojects is in accordance with the guidelines and criteria laid down by the program.

Evolving a local government body that is democratic, transparent, representative and accountable, will take considerable time and resources. Adopting the strategies outlined in this paper, including a media campaign, the capacity of local government and of local institutions will be strengthened. Nevertheless, close monitoring of the participatory processes at the community and local government level is required to ensure that the resources are not captured by influential local elites. Furthermore, training inputs will be required to enable local government to develop the technical and administrative capacities to respond to needs of resource appropriators and take on planning responsibilities. In the initial stages, close involvement of the de-concentrated units of the implementing agency and specifying MYPCs for each community and earmarked for NRM will assist in ensuring program goals are met and leakages are minimized.

Management of common pool resources is critical for the sustainable and effective management of natural resources. This would require all resource appropriators to participate in an institution for collective action and receive program inputs and benefits to avoid the problem of free-riders undermining the authority and control of the institution. The most efficient means of targeting all resource appropriators in an area is to adopt a geographic targeting mechanism as opposed to one based on wealth or some other criterion. If the target geographic area is suffering from extensive degradation of natural resources, then all appropriators are equally affected and deserve access to program benefits. However, if the geographic area also includes a high degree of inequity, for example, in terms of size of land holdings, then there is an important trade-off in adopting this approach to targeting; wealthier resource appropriators would receive the same benefits as poorer appropriators. Obviously, some local level targeting can be incorporated, for example, institutions consisting of poorer resource appropriators may decide to exclude large farmers from receiving program benefits, or they may require wealthier households to contribute a greater proportion of the capital cost. In any case, decisions of this nature must be taken through democratic participatory processes involving all resource appropriators; they are best placed to understand the local political consequences of such actions and adopt appropriate rules to dissuade some appropriators from free-riding on the actions of others.

The Bank’s guidelines regarding community procurement of goods and services have recently been revised (Gopal and Marc, 1994). The overall goal in revising the guidelines has been to empower local groups to manage financial resources and procure quality goods and services in the most cost-effective way (Narayan and Ebbe, 1997). In over one-third of Social Fund projects, community groups have authority to hire, procure materials and/or supervise contractors. It is this aspect of the Social Funds that has contributed to the remarkable increases in cost and time efficiencies in subproject construction over conventional forms of procurement (World Bank, 1997c).

Conventional competitive bidding procedures required the participant to have some degree of institutional and financial support, and knowledge of commercial bidding. Gopal and Marc (1994) found that these methods excluded participation of community groups because they lacked support, administrative capacity, and were unfamiliar with commercial practices. Guidelines have since been revised and adaptations of local competitive bidding have been developed to encourage local contractors and community groups to bid for small projects. In addition, variations of local shopping procedures are also used based on soliciting two or more quotes from local suppliers.

Increased flexibility in procurement of goods and services requires additional mechanisms to ensure accountability and transparency in the use of funds. Box 11 lists some common practices now used by Social Funds to increase accountability and transparency.

|

Box 11. Mechanisms Employed by Programs to Encourage Accountability Unit Costs. Establishing standard prices for the completion of various types of subprojects. These prices are updated on a regular basis by using a technical auditor. Focus on Outputs. Disbursal of funds against a physical verification that the structure has been built. This can only be used where: (i) there is a physical output that can be described in physical terms; (ii) the cost of construction is fairly uniform; and, (iii) the existence of the output can actually be checked. In many projects using this approach, the quality of construction has been an issue. However, quality can be assured through use of technical assistance paid for by the program. Standard Contracts. Standardized contracts can be used: (i) between the program and local institution; (ii) between the local government body and the local institution; and, (iii) between the local institution and suppliers of materials and/or services. This takes into consideration that many local government bodies and local institutions may lack the capacity to develop appropriate contracts suited to the legal framework of the country or the Bank. Standard Designs for Subprojects. This is particular appropriate for small or simple infrastructure. It reduces the need for each community to reinvent the wheel. The designs should be developed during a pilot phase and take into account local knowledge of men and women. Locations of the structures should still be decided by each institution as part of a participatory micro-level planning exercise. Implementation manual. All Social Fund projects provide the implementing agency with a Manual of Instructions. This usually contains project execution guidelines; sample bidding documents; procedures; responsibilities; subproject selection criteria; etc. This should be developed during the pilot phase and refined during implementation based on monitoring and evaluation of program progress and impact. Beneficiary Contribution. Beneficiary contributions can increase the community commitment to the subproject and may ensure greater accountability through peer pressure. Contributions can be in a number of ways. Usually it is either in the form of cash, materials, or in-kind voluntary labor. Additional and innovative forms of contribution need to be explored. In particular, production forgone through the adoption of resource conserving technologies, or land taken out of production due to the construction of a conservation structure. The percentage of beneficiary contribution needs to take into account a number of factors - see section 0 for more details. Blacklisting of contractors/NGOs. Based on program experience, contractors and NGOs that are found to be fraudulent or inefficient need to blacklisted and this information shared with local government and local institutions. Sanctioning local institutions/local government. Institutions and local authorities found to have misappropriated funds can be sanctioned by having their MYPC reduced or removed. This can stimulate peer pressure for accountability and also act as a demonstration for others. Management Information Systems and Monitoring. Well designed and implemented MIS and monitoring systems can provide up to date information on the physical and financial progress of the program and its impact. The numbers can act as a check on whether funds are being judiciously used. In addition, beneficiary assessments, and the use of random audits of local institutions and local government can assist in mobilizing peer pressure to minimize misappropriation of funds.

|

Advance payments to local government and local institutions is essential to minimize delays of disbursal, facilitate local procurement of good and services, and ensure quick accrual of benefits. Often, legal agreements between the funding agency (central or state government) and local government or institution are required in order to permit release of funds (Gopal and Marc, 1994; Narayan and Ebbe, 1997). In addition, this requires local institutions to open Bank accounts for the handling of funds. Social Fund projects have developed a range of mechanisms and procedures for advance payment and verification of the judicious use of funds.

In the NRDP, all subproject proposals are assessed by the State Technical Units. Staff physically visit the communities and verify that the subproject is technically feasible and that all the beneficiaries are indeed eligible to receive benefits. After approval of a subproject proposal by the MDC, funds are released to the Community Association in two or three tranches depending on the cost of the subproject. Release of additional tranches are contingent upon Community Associations providing receipts of expenditure incurred and/or physical verification that construction has commenced. Given that the maximum cost of a subproject is US$ 40,000, the liability for embezzled funds is therefore confined.[25]

World Bank (1997c) and Narayan and Ebbe (1997) define demand orientation as when projects offer clients a range of options from which to choose (e.g. options in goods and services, technology, and service levels); provide impartial information to assist clients in making informed decisions; and require evidence of commitment and interest through cash or in-kind contributions from beneficiaries. There is an implicit assumption that programs need to be become more demand orientated in order to increase the likelihood for community ownership of the investments and ensure their sustainable operation and maintenance.

Unfortunately, in programs seeking to promote sustainable management of natural resources, demand orientation is not straight-forward. As already mentioned, resource appropriators will not necessarily identify natural resource management activities as a priority, even if they have complete information about the extent of degradation and the costs and benefits of intervention. The fundamental issue preventing demand from being expressed by resource appropriators is related to the common pool dimension of most resource management activities and the associated problem of asymmetric costs and benefits and free-riders. Empirically, it can be seen that all of the programs that have managed to effectively promote community-based natural resource management have had to invest considerable resources in participatory planning exercises and social organizing to elicit demand for NRM interventions. Moreover, all programs have restricted the choice of subprojects to those that are specifically natural resource management related. Admittedly, some programs have used entry-point activities not related to NRM but, instead, addressing a priority concern of the majority of resource appropriators (for example, productive infrastructure such as a road, or drinking water). Nevertheless, usually, only one non-NRM entry point is allowed; all subsequent subprojects must address resource management issues.

Therefore, the demand orientation of a community-based NRM program cannot be ensured through providing a wide choice of subproject options to clients. Instead, it needs to rely upon awareness raising amongst appropriators and local government about environmental degradation and how it can be addressed while also providing individual productive benefits. It also needs to based upon effective participatory planning processes to stimulate demand. As mentioned in section 0, page 42, a phased approach to implementation using nodes, can contribute to creating effective demand; resource appropriators will then be able to approach the implementing agencies and demand participation in the program.

|

[21] Originally designed for

emergency assistance, objectives for Social Fund projects have evolved towards

community development for sustainable service delivery to the poor (World Bank,

1997c). [22] The selection of an appropriate level of local government is guided by the need for area and population covered to be small enough to facilitate direct popular participation and interaction between local authorities and communities and the need to be viable planning units. It is also determined by whether local government already exists and if these are to be strengthened and empowered through decentralization legislation. [23] The amount of MYPC should be determined by a transparent formula that is simple enough to be constructed based on existing, or readily obtainable, disaggregated data (Romeo, 1996). Ideally, it should take into consideration the size of population (per capita index), local levels of infrastructure and services, and a composite index of the extent of natural resource degradation. [24] Despite a positive evaluation of most aspects of the program, it is not clear whether the MDCs are truly representative of all the potential beneficiaries of the program. In particular, there is some question about the extent of participation by poor and vulnerable groups in the Community Associations which initially prioritizes subprojects. Moreover, the process of prioritization of subprojects by MDCs is, in practice, unclear and not transparent; the influence of the Mayor and other local elites in subproject identification and prioritization can be considerable in some areas (See Esmail and McLean, 1997 forthcoming). [25] In some States, for example Maranhao, initially some executive members of Community Associations absconded with the first tranche of funds released to them. Subsequently, the Technical Units paid contractors directly and only released a small proportion of the subproject cost to the CAs to cover incidental expenses. Once a CA had developed a track record in efficient handling of funds, funds are released directly to them and they were given authority to make all necessary payments. |