River systems are in many cases not confined to one country. Activities in a river catchment may therefore have a direct effect in other countries. Co-operation between countries concerning these activities is thus crucial for sustainable management of the river resources. Cross border activities include water abstraction, pollution, river siltation, catchment deforestation, etc., but also include the introduction of aquatic species.

All over the world aquatic species have been introduced and translocated for the purpose of improving the production from aquatic systems. Some of these introductions have led to increased production, while many of them have not had the desired effect. Conversely, several introductions have had negative impacts on the natural habitat by displacing indigenous aquatic species directly through predation or competition as well as indirectly by changing the aquatic environment.

Aquatic ecosystems are complex and the understanding of various systems is still limited. The possible effects of any management practice are therefore difficult to predict, while their impact may be detrimental to the ecosystem, as well as to the biodiversity of the overall system.

A technical Consultation on Species for Small Reservoir Fisheries and Aquaculture in Southern Africa was held in November 1994 in Livingstone, Zambia and was attended by 52 participants from within and outside the region. This consultation reviewed the situation regarding the introductions of species and recommended that the inter-country co-operation in relation to the management of shared water systems should improve, and consultations between the countries should be formalised.

During the present review the factors influencing fish distribution were assessed. The status of exotic introductions in the Limpopo River and the official status of the individual countries sharing its catchment were reviewed, and discussed in consultation with key persons from the region. List of participants is given in Appendix 1. The information presented in this report is a compilation of views, experiences and results of discussions from these participants.

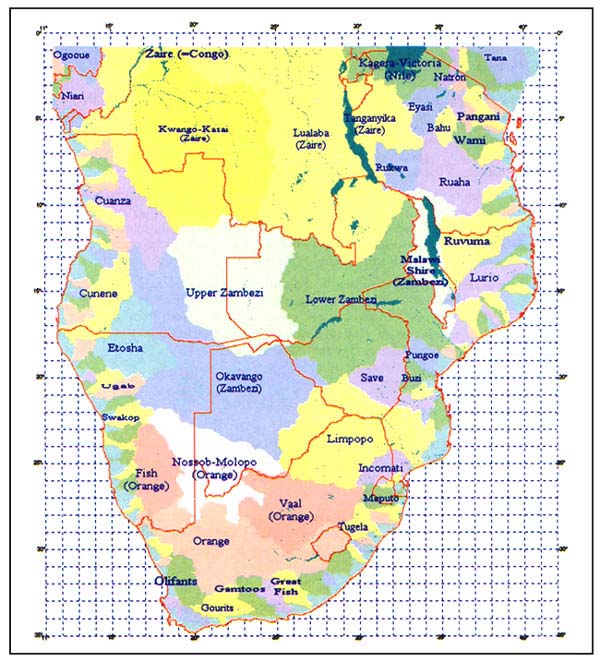

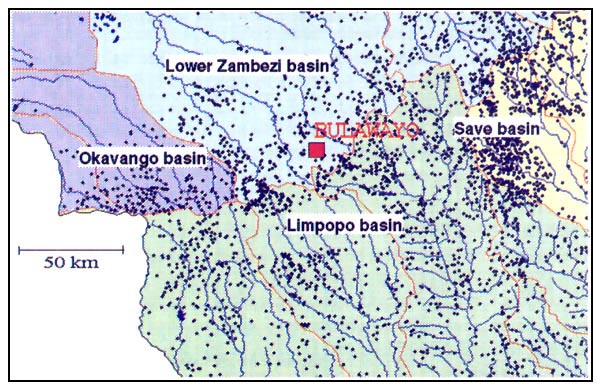

Rivers transport water from rainfall towards points of lowest altitude. In most cases the water is ultimately transported to the oceans, although internal catchment basins exist. Before reaching the oceans, different rivers join each other making a dendritic arrangement of streams throughout the drainage basin. Each river system drains part of a continent, the drainage systems in southern Africa are given in Figure 1.

Rivers can be separated on the grounds that they each drain their own catchment area, and are in no direct contact with each other. This differentiation is easy to maintain in the upper reaches of rivers, but becomes less clear in the lower reaches. If rivers drain in flat coastal areas, seasonal floodplains may join several river systems.

Along its way to the ocean, rivers take many different forms and shapes, and differences between the various zones of one river are often greater than between homologous zones of different rivers. The landscape as well as the rainfall pattern impose certain characteristics on the rivers. Annual water fluctuations in rivers may be very moderate in areas of constant rainfall or constant release of water through the presence of lakes, swamps, heavy forests, or floodplains near their headwaters. Floodrivers on the other hand are characterised by extreme annual fluctuations in water level from severe flood to sometimes complete dissipation in the dry season, caused by significant seasonal variations rainfall and poor water retention capacity of the land near the headwaters.

Figure 1: Watersheds in subequatorial Africa

River management and water management in general is aimed at the development of water resources for human use, being urban supplies, irrigation or industrial use. This has in the past led to over-exploitation and unsustainable use of the resource. This has recently been recognised by most stakeholders and there is now a general consensus that for sustainable use of the water, protection of the water resource should prevail over pure development or exploitation. It is also generally recognised that water is but one component of the whole aquatic environment and that protection and management of water must address the integrity and function of aquatic ecosystems. This brings with it the need to address the links between land and water systems through integrated catchment management.

The larger river systems in southern Africa are shared between various countries. Table 1 presents the shared river systems in southern Africa. Integrated catchment management demands collaboration between different authorities within one country, but in cases of shared rivers also requires collaboration between different countries.

Table 1: River systems shared by different countries in southern Africa

| River system | URT | MOZ | MLW | ZAM | ANG | NAM | BOT | ZIM | RSA | SWA | LES |

| Zambezi | |||||||||||

| Limpopo | |||||||||||

| Orange | |||||||||||

| Incomati, Maputo, Umbuluzi | |||||||||||

| Ruvuma | |||||||||||

| Save/Runde | |||||||||||

| Cunene | |||||||||||

| Lake Chilwa | |||||||||||

| Etosha watershed |

The approach of integrated catchment management, and ensuring the protection and ecological and environmental integrity of these systems, will lead to a more sustainable use of the water resources. However, this requires a change of the present management, and in the short term reduced access to the resource for some. This change in management will therefore most likely meet resistance from some users. Overcoming this resistance will be especially difficult when agreements on implementation have to be made between different countries. Effects of certain management decisions may be felt more in one country while the benefits for that same country may be less tangible.

Integrated catchment management encompasses many different intermediate objectives, goals and activities. The prevention and control of introduced species in a catchment is only one of the activities to improve the overall management of a river system (Figure 2).

The International Convention on Biodiversity stated that urgent and decisive action is needed to conserve and maintain genes, species and ecosystems, with a view to the sustainable management and use of biological resources. The introductions of aquatic species are generally seen as an important cause of habitat alteration and have caused a loss of aquatic biological diversity in many places around the world.

Figure 2: Introduction of aquatic species as part of overall integrated catchment management

Prevention of further introductions however does not imply a direct change in the present use of the water resource, and although it may impact on future economic activities in the catchment, it does not change the present utilization. Immediate and powerful opposition towards changes in the policy on introductions of aquatic species in a river system should therefore not be expected.

The introduction of an aquatic species is not necessarily a matter of internal affairs but will have a direct impact in other countries sharing the same system, and cross boundary collaboration should be initiated to discuss this issue. The more countries involved in such discussions the more complicated the issue becomes and the less likely a solution will be identified. It was therefore deemed appropriate to start with a river system that is only shared by a few countries, and where countries have identified the need to collaborate on the issue of introductions of aquatic species. The Limpopo River System meets these criteria, and it was argued that results for this review can be used as an example for collaboration on this issue for other more complex aquatic systems.

Fishes are the most numerous of the vertebrates in the world; around 50% of all the vertebrate species are fishes. Fish species evolved much earlier than the other vertebrates and thus had more time to develop a wide variety of species. However, the fact that fish live in water is an important aspect for explaining the differences in species and their distribution. The determinants of fish species distribution can be categorized into physical, biological, ecological and human factors.

Freshwater systems are usually restricted and well defined. Consequently the distribution of freshwater organisms, and particularly fishes, is often more distinct and restricted than that of other animals. The physical boundary of a particular water body is the most obvious limit to fish distribution. Fish in one river system are in no direct contact with species in an other river system and can develop independently.

River systems are much less separated from the point of view of fish movements than from the point of view of water movements. River systems are generally separated on the basis of drainage, and although waters from different systems may mix in the coastal floodplains, this connection between different rivers is only seasonal. Fish however can use this seasonal and more sporadic contact of waters from different rivers systems to move from one system to the other. From the point of view of fish distribution river systems are therefore much less distinctly separated.

The rivers and lakes do change over time in accordance with geological processes such as mountain building, rifting and erosion. The distribution of the redfin minnows in South Africa is explained by such changes in river systems. The species Pseudobarbus quathlambae, found in the upper reaches of the Orange river in Lesotho, is closely related to the Pseudobarbus species found in the rivers of the western and southern Cape. These rivers, however, clearly belong to a separate river system with no connection to the rivers of the Orange Basin. This fish distribution can be explained by the fact that the upper reaches of the Cape rivers were previously all part of the Orange River System. Through changes in geology these upper reaches were captured in separate coastal rivers and the species were transferred to these coastal systems.

The distribution of Kneria auriculata found in the upland streams of the Pungwe, Buzi and Save in Zimbabwe and Mozambique as well in the Crocodile River of the Incomati system in South Africa, can be explained by the fact that these rivers were previously part of the Limpopo System, but as the river changed its course the species became isolated in two different distinct river systems.

Within one river there is typically a succession of types of water course from steep slopes near the source to minimal slope near the mouth. This succession is by no means adhered to, and rivers show several successive reaches of floodplains and rapids along their length. Fish species distribution alters with these changes in gradient and water flow. Lentic species are only found in stagnant or slow flowing waters while others require fast flowing waters (i.e. lotic species). The depth of the water has also a direct effect on the fish species distribution. Larger fish are generally found in deeper waters, smaller ones in the shallows.

Certain fish species are adapted to live in seasonal waters; they either survive dry periods, produce eggs that are adapted to drought and hatch during the next flood, or migrate from permanent waters to the seasonal streams and pools. Seasonal streams therefore accommodate fish species different from permanent rivers.

The fact that fish are poikilothermic while water is the medium of their environment, ensures that fish are under a much greater influence of their environment than most terrestrial organisms. The water quality in terms of oxygen content, salinity, hardness, acidity and temperature is of direct influence on the physiological processes of a fish. Most fish are able to cope with only a certain range of these water quality parameters, and when these change this is directly reflected by a change in the fish population.

An organism has to find its own place in an environment, where it will be able to compete successfully with other species for food and space, it has to find an environment suitable for reproduction and must be able to avoid predation. Fish species have developed specific strategies to cope with their environments. Typically these strategies can be characterised as altricial or precocial. Species with an altricial life style show a high adaptability towards changes in their environment, use a wide range of feeds, and can be characterised as generalist or invaders. They are found in unstable and unpredictable environments, where mortality is determined by the environmental conditions and not by stock densities. Their reproduction is adapted to the unpredictable situation, producing large numbers of consequently small eggs. Fish species with a precocial life style can be found in stable environments, and are highly specialised. They live in an environment where the aquatic community has established a stable biological equilibrium. Mortality is density dependant and fluctuation in population composition is low. Their reproduction strategy is focused on quality instead of quantity. They produce limited numbers of eggs and offspring but produce large eggs and in many cases take care of their offspring.

Table 2: Characteristics of environment and organisms in predictable and unpredictable environments.

| Traits-environment | Unpredictable | Predictable |

|---|---|---|

| Inertia | low | high |

| Elasticity | high | low |

| Amplitude | high | low |

| Dynamics | robust | fragile |

| maturity | low | high |

| Traits-organisms | ||

| Species diversity | low | high |

| Interdependence | low | high |

| Species rarity | low | high |

| Migrations | high | low |

| resource defence | low | high |

| niche overlap | high | low |

Fish have adapted their strategy to the predictability of the environment, therefore different species communities are found in an environment with minimal fluctuations than in unpredictable environments. In a predictable environment the species diversity is high, these species are very specialised and are sometimes endemic to that particular environment. Table 2 gives the differences between populations in a predictable and unpredictable environment.

Through manipulation of the environment, human activities have indirectly increased as well as decreased the distribution ranges of fish species. Fish communities are adapted to an environment and the populations have established a balance within this environment. Activities that change the conditions will have a direct influence on the aquatic communities.

The construction of dams and weirs have obstructed free movements of fish along the rivers, while they have also created new environments. The reservoir environment is suitable for some species while others have disappeared from these new systems. Other changes in the catchment and wetlands have altered the environments, favouring some species but with negative effects for many others.

The connection of river systems with the purpose of improving the water supply to areas with water shortages have created a possibility for fish to move from one river system to another, and so expanding the distribution range of the fish.

People have introduced several aquatic species and so directly influenced the distribution of these and other species.

Introduced species can be defined as species intentionally or accidentally transported and released by man into an environment outside its natural range.

Although there are many different native species of fish in southern Africa, a large number of species have also been introduced. Introductions have occurred for the purpose of fishing, to increase the production of lakes and rivers, or to improve the sport fishing opportunities. In some instances the creation of new environments has promoted the introduction of species that would occupy the new and vacant niches, like the introduction of Limnotrissa miodon into Lake Kariba.

Most introductions have been made for the purpose of aquaculture. The main reason for using introduced species is that the culture techniques of these species are well known and information is available. Food producers try to minimise risks by using technologies, including fish species, that are already well established. Aquaculture is conducted in controlled systems, but even if these fish are used in strictly confined areas for farming only, there is still a high risk of fish escaping and finding their way to natural waters.

Whether or not these introduced species will establish viable populations in natural water depends on many factors. The species has to be adapted to the physical environment but also has to find its ecological niche. The ecological resistance, a system of checks and balances opposing the invasion of a new species into natural ecosystems, is generally lower in unstable and unpredictable environments than it is in stable environments. However, the introduced species still has to be able to cope with this environment, and species with an altricial life style will probably establish themselves more easily than other species.

The ecological resistance of a stable environment is often much higher than that of unpredictable environments. The communities in these environments have a high and complicated species diversity with most niches filled by highly specialised fish species. However, the success of an introduced species to establish itself becomes much greater when the ecology of the systems is disturbed. A disturbance creates threats to many species but at the same time opportunities for others. Human activities have an influence on the composition of the species originally present, but may also influence the changes of introduced species to establish viable populations.

This does not mean that introduced species will never get established in stable communities with a high degree of specialisation. The introduction of Nile perch, Lates niloticus in Lake Victoria is a striking example of a situation where an introduced species has had a great impact on the extremely diverse cichlid population.

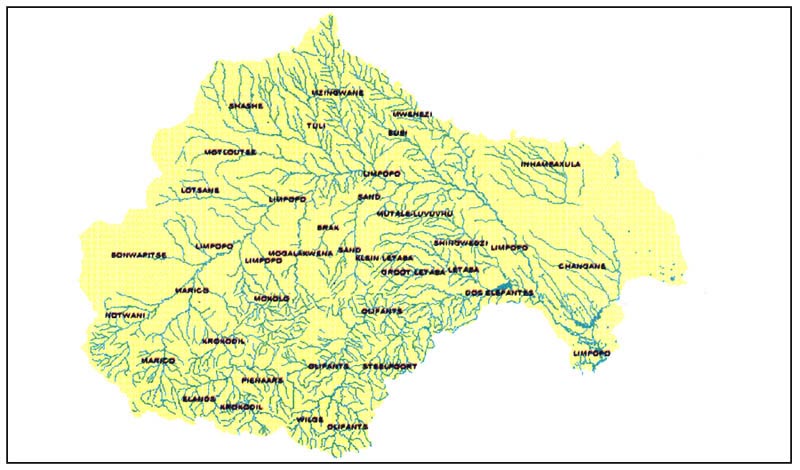

The Limpopo System, situated between the 20 and 26 degrees south and 25 and 34 degrees east, drains extensive areas in Botswana (91500 km2), South Africa (183800 km2), Zimbabwe (62200 km2) and Mozambique (92500 km2). The Limpopo River itself forms a lengthly boundary between Botswana and South Africa and makes up the whole boundary between South Africa and Zimbabwe. Figure 3 shows the river and its main tributaries.

The fish life of the whole Limpopo Systems has never received the attention it deserves, partly as a result of the political division of the catchment and the fact that most of the Limpopo River itself forms international boundaries. As a result of the lack of earlier information on the hydrology as well as biota, recent changes and environmental deterioration have not been recorded.

The total number of recorded species in the Limpopo System is 83, see Table 3. Of these 48 species are found in the Limpopo River itself, while the others are only recorded in its tributaries. As a result of the relatively short period of isolation from other river systems, and due to the characteristics of the system, the Limpopo Systems has relatively low endemicity, only three species are restricted in their distribution range to this system.

Eighteen introduced fish species have established populations in the Limpopo River System, of which six are in the Limpopo River itself. There have been various reasons for introducing these fish species, improving the sport fishing opportunities in dams in the catchments has been an important motive. Fish have then escaped from these dams and established populations in the river system.

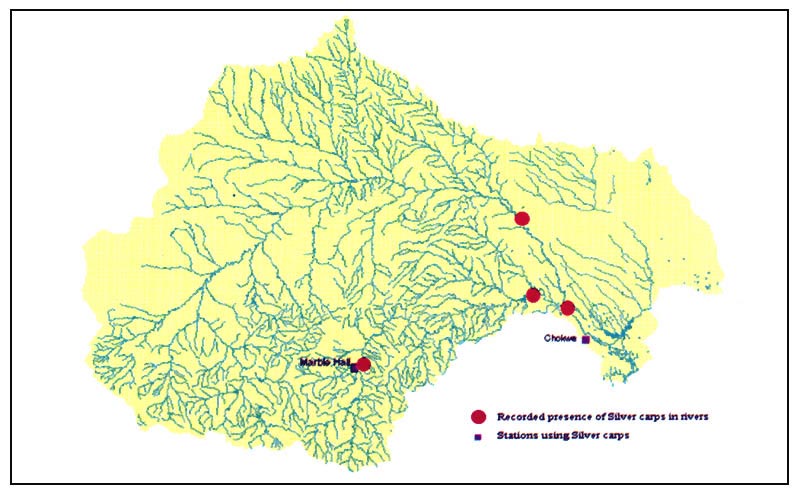

The group of the Chinese carp, the Grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella the Silver carp, Hypophtalmichthys molitrix, and the Bighead carp, Hypophthalmichthys nobilis, have been and are being used inside the drainage basin of the Limpopo. In South Africa the Silver carp and Grass carp have been stocked in the Arabie dam near Marble Hall on the Olifants river, while stocks of all three species are being kept at the Mapapa Station on the Elefantes river near Chokwe in Mozambique. Grass carp were introduced with the objective to control excessive aquatic vegetation in impoundments and irrigation canals, while the Silver carp was introduced to increase fish production from these waters.

Grass carp and Silver carp normally do not breed outside their natural range as they require special environmental conditions for successful breeding. Despite these specific requirements, these species have established breeding populations in several rivers in Asia, Europe and North America. It has been observed in South Africa that Grass carp develop to a point of breeding readiness and remain in this stage throughout the season. Silver carp have already reproduced in the Arabie dam, have established a breeding population in the Limpopo System, and have been recorded well up into the Limpopo River itself (Figure 4).

Silver carp are basically phytoplankton feeders and after introduction will compete with other species for this food source. Silver carp however will have little effect on the habitat and their overall negative impact on the ecosystem might be limited.

Grass carp feed mainly on aquatic vegetation, and are able to consume large quantities of plant material (e.g. consuming up to their own body weight daily) If present in high densities, Grass carp are able to eradicate submerged plants and will drastically alter the vegetation profiles of the water they inhabit.

Figure 3: The Limpopo River System

Figure 4: Recorded presence of Silver Carps in Fish Culture Stations and Rivers.

Table 3: Fish species recorded in the Limpopo river catchment

| Species | Common Name | Present in Limpopo itself | Introduced Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAMILY AMPHILIIDAE | |||

| Amphilius uranoscopus | Stargazer mountain catfish | ||

| A. natalensis | Natal mountain catfish | ||

| FAMILY ANGUILLIDAE | |||

| Anguilla mossambica | Longfin eel | * | |

| A. bicolor bicolor | Shortfin eel | * | |

| A. marmorata | Madagascar mottled eel | * | |

| A. bengalensis labiata | Africa mottled eel | * | |

| FAMILY APLOCHEILIDAE | |||

| Nothobranchius furzeri | Turquoise killifish | ||

| N. orthonotus | Spotted killifish | ||

| N. rachovii | Rainbow killifish | ||

| FAMILY AUSTROGLANIDIDAE | |||

| Austroglanis sclateri | Rock catfish | * | |

| FAMILY CENTRARCHIDAE | |||

| Lepomis macrochirus | Bluegill sunfish | * | |

| Micropterus salmoides | Largemouth bass | * | |

| M. dolomieu | Smallmouth bass | * | |

| FAMILY CHARACIDAE | |||

| Brycinus imberi | Imberi | * | |

| Micralestes acutidens | Silver robber | * | |

| Hydrocynus vittatus | Tigerfish | * | |

| FAMILY CICHLIDAE | |||

| Pseudocrenilabrus philander | Southern mouthbrooder | * | |

| Chetia flaviventris | Canary kurper | ||

| C. brevis | Orange-fringed largemouth | ||

| Serranochromis meridianus | Lowveld largemouth | ||

| S. robustus jallae | Nemwe | * | * |

| S. thumbergi | Brownspot largemouth | * | |

| Tilapia sparrmanii | Banded tilapia | * | |

| T. rendalli | Redbreast tilapia | * | |

| Oreochromis mossambicus | Mozambique tilapia | * | |

| O. macrochir | Greenhead tilapia | * | * |

| O. niloticus | Nile tilapia | * | * |

| Pharyngochromis acuticeps | Zambezi happy | * | * |

| FAMILY CLARIIDAE | |||

| Clarias gariepinus | Sharptooth catfish | * | |

| C. ngamensis | Blunttooth catfish | * | |

| C. theodorae | Snake catfish | ||

| FAMILY CYPRINIDAE | |||

| Barbus afronamiltoni | Hamilton's barb | * | |

| Barbus aeneus | Smallmouth yellowfish | * | |

| B. annectens | Broadstriped barb | * | |

| B. anoplus | Chubbyhead barb | * | |

| B. bifrenatus | Hyphen barb | ||

| B. brevipinnis | Shortfin barb | ||

| B. euteania | Orangefin barb | ||

| B. lineomaculatus | Line-spotted barb | * | |

| B. marequensis | Largescale yellowfish | * | |

| B. mattozi | Papermouth | * | |

| B. motebensis | Marico barb | ||

| B. neefi | Sidespot barb | ||

| B. pallidus | Goldie barb | ||

| B. paludinosus | Straightfin barb | ||

| B. polylepis | Smallscale yellowfish | ||

| B. radiatus | Beira barb | * | |

| B. toppini | East coast barb | * | |

| B. treurensis | Treur River barb | ||

| B. trimaculatus | Threespot barb | * | |

| B. unitaeniatus | Longbeard barb | * | |

| B. viviparus | Bowstripe barb | * | |

| Cyprinus carpio | Common carp | * | * |

| Hypophthalmichthys molitrix | Silver carp | * | * |

| Labeo congoro | Purple labeo | * | |

| L. cylindricus | Redeye labeo | * | |

| L. molybdinus | Leaden labeo | * | |

| L. rosae | Rednose labeo | ||

| L. ruddi | Silver labeo | * | |

| Labeo umbratus | Moggel | * | |

| Mesobola brevianalis | River sardine | * | |

| Opsaridium peringueyi | Barred minnow | * | |

| Varicorhinus nasutus | Shortsnout chiselmouth | ||

| FAMILY CYPRINODONTIDAE | |||

| Aplocheilichthys johnstoni | Johnston's topminnow | ||

| A. katangae | Striped topminnow | ||

| FAMILY GOBIIDAE | |||

| Awaous aeneofuscus | Freshwater goby | * | |

| Glossogobius callidus | River goby | * | |

| G. giuris | Tank goby | * | |

| Redigobius dewaali | Checked goby | * | |

| FAMILY MEGALOPODIDAE | |||

| Megalops cyprinoides | Oxeye tarpon | * | |

| FAMILY MOCHOKIDAE | |||

| Chiloglanis paratus | Sawfin suckermouth | * | |

| C. pretoriae | Shortspine suckermouth | ||

| C. swierstrae | Lowveld suckermouth | * | |

| Synodontis zambesensis | Brown squeaker | * | |

| FAMILY MORMYRIDAE | |||

| Marcusenius macrolepidotus | Bulldog | * | |

| Petrocephalus catostoma | Churchill | * | |

| FAMILY PERCHIDAE | |||

| Perca fluviatilis | Perch | * | |

| FAMILY POECILIIDAE | |||

| Gambusia affinis | Mosquitofish | * | |

| Xiphophorus helleri | Swordtail | * | |

| FAMILY PROTOPTERIDAE | |||

| Protopterus annectens brieni | Lungfish | * | |

| FAMILY SALMONIDAE | |||

| Salmo trutta | Brown trout | * | |

| Oncorhynchus mykiss | Rainbow trout | * | |

| FAMILY SCHILBEIDAE | |||

| Schilbe intermedius | Silver catfish | * |

With the removal of the vegetation through Grass carp grazing and the resulting increase in turbidity, the aquatic habitat generally degrades and aquatic life will be negatively affected. So far as is known, the Grass carp have not reproduced in the Limpopo System but, seen the reproduction of Silver carp, this possibility should not be ignored.

Legislation and associated regulations concerning the introduction of aquatic species can be enacted at international, regional, bilateral and national levels. Legislation is passed by parliament or equivalent fora. It usually enables a person such as the Chief Fisheries Officer to draw up regulations to implement the general laws contained in the legislation. Regulations are therefore subsidiary legislation.

An introduced species can be defined as a species that does not naturally occur in the area but has been introduced to it from outside that area. This definition is related to physical boundaries and not political ones. They are therefore not always compatible with those contained in national legislation. Words used in national legislation are imported, non-indigenous, native, transferred and introduced. Interpretation of these words may vary between countries.

The Department of Water Resources under the Ministry of Energy and Water Resource Development is responsible for the provision and conservation of water. It has the mandate to control water pollution nation wide and delegates its functions to provincial Water Engineers and Local Authorities. The Water Pollution Control Section is responsible for the co-ordination of activities by these bodies and for ensuring that a uniform and consistent approach to water pollution is applied throughout the country.

The functions of the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), under the Ministry of Environment and Tourism, are to promote the adoption of objectives or standards relating to environmental quality and pollution control, mitigate any adverse environmental impacts of new projects and provide Zimbabweans with information on environmental issues. The DNR has the responsibility to assist other government departments and to work with provincial authorities and the public to conserve and enhance the quality of the environment. DNR emphasises environmental awareness, environmental research, soil conservation, water resource management, forest management and the monitoring of mining activities.

Under the same Ministry, the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Management (DNPWM) has legal responsibilities that are limited to state lands. The department has no legal obligations to work in communal lands except where stray indigenous animals represent a threat to human life. The aims of this department are to conserve wildlife and biological diversity and to promote sustainable use of natural resources. The introduction and transfer of fish falls under the responsibility of this department as defined in the National Parks and Wildlife act of 1975.

The act states that:

“No person shall-

without reasonable excuse, the proof whereof lies on him, introduce into any waters any species of fish or any aquatic plant which is not native to such water; or

import any live fish or the ova of any fish;

except in terms of a permit issued in terms of section 83.”

The section 83 states that:

“Subject to the provisions of this Act, the Minister may issue a permit to any person to…

introduce into any waters any fish or aquatic plant of a species which is not native to such water or water naturally connected thereto: Provided that no such permit shall be issued in respect of any aquatic plants which is a weed;

import live fish or the ova of any fish.”

The DNPWM has proposed to use Grass carp for weed control in reservoirs around Harare. If this species is to be stocked, only triploids will be used in order to prevent the presence of fish that may have the potential to establish breeding populations.

The major responsibility for water in Botswana falls under the Ministry of Mineral Resources and Water Affairs. The ministry and its various departments are responsible for the use of water in aquifers, the distribution of water, the design and construction of water systems, the exploration of water aquifers, the monitoring of water flows the testing and analysis of water, the disposal of waste water, and the establishment of a licensing body for the use of the water.

The Ministry of Commerce and Industry is responsible for the management of water resources within their areas of jurisdiction, i.e. game reserves and parks.

The Ministry of Agriculture is responsible for the protection and management of watersheds. The fish protection act provides for the making of regulations by the Minister of Agriculture:

"The Minister may make regulations which shall apply to such areas as are specified therein, providing for the more effectual control, protection and improvement of fish, and the government and management of any specified area in which fishing may be carried on, and without prejudice to the generality of the foregoing for all or any part of the following purposes....

prohibiting, restricting or regulating the bringing into Botswana of any live fish;

prohibiting, restricting or regulating the transfer within Botswana of any live fish.”

The Department of Water Affairs is under the Ministry of Public Works and Housing and has the responsibility for the management of water resources at a national level. The Regional Water Administrations are organised on the basis of river basins and are responsible for water resource administration in their respective regions.

In 1991 a National Water Council was created as an intersectoral water development co-ordinating council at ministerial level. It is in charge of the relevant aspects of the general water management policy and assumes responsibility for its compliance.

In 1995 a National Water Policy was approved. One of the main principles of the policy is the integration of water resource management. It uses the approach that water should be allocated through integrated river basin management in order to optimise the benefits to the community. It also takes into account the environmental impacts and water conservation. The Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries is a member of this council.

Mozambique does not have clear regulations concerning the introduction or use of fish. The present legislation dates from 1960 and states that:

The Secretary of State for Fisheries, in co-ordination with the Ministry of Agriculture should determine necessary measures for the development of aquaculture, namely:

rules required for the introduction of new species.

The Secretary of State for Fisheries can define measures to conserve the fisheries resources, namely:

adopt any other conservation measures necessary for the preservation of fish resources.

These regulations are not adjusted to the present situation in the country, and the country faces problems with over-exploitation, and uncontrolled catching and exporting of ornamental fish, corals, etc. Efforts are being made to improve the legislation, for which cross-border collaboration is seriously considered.

Mozambique participates in a programme to conserve the biodiversity of Lake Malawi/Niassa. One of the activities under this project is to harmonise the rules regarding introductions of new species and management of the lake between the three countries sharing this system.

The custodianship of the water resource of South Africa is the responsibility of the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF) at national level. Water is recognised as a precious national asset, to be managed for the public good. Management and planning of the water resources at national level are essential given the fact that water resources are very unevenly distributed in relation to centres of population and development. This has made inter-basin water transfers necessary on regional, national and international scales.

The new water policy, which is presently in its final stage of preparation, has three important aspects:

the move away from resource development to water resource management;

the commitment to protection of water resources in order to ensure sustainable management;

the recognition that water is but one component of the whole water environment.

The DWAF is responsible for macro-scale planning of water resources development. Their task is to reconcile demand with supply on a sustainable basis, to assess possible water supplies, and to draw up proposals for investigating the feasibility of water resource developments.

Over the last few years there has been some provision made for “water for the environment” in the planning of water resources. Initially the environment was seen as a competing water user, but it is now recognised that aquatic ecosystems actually are the resource base, and the maintenance of their functions and integrity is essential to sustainable utilisation.

The Directorate of Water Quality Management, under the DWAF, sets national policy and guidelines for water quality management in South Africa. In the past the DWAF has had a limited ability to control land uses which generate nonpoint source pollution. Land use, planning, control zoning and management are generally functions of provincial government or of other national government departments. Frequently the objectives of these other departments can conflict with the requirements for protection and management of water resources. The new water policy addresses the need for DWAF to collaborate with other government departments to jointly identify the best management practices which will prevent or reduce the impacts of nonpoint sources on water resources.

Regulations relating to introductions are dealt with within the nine provinces. These provinces have been operating under the old ordinances but are now autonomous in their regulations and are preparing their own acts under the new governmental system. The National Aquatic Conservation Committee (NACC) has been set-up to determine policy for aquatic imports and releases in order to achieve compatibility between the provinces. Their policy statement is uniform for all provinces, but the implementation may differ between provinces.

The importation of non-indigenous aquatic species requires approval and a permit from a regional Department of Nature Conservation. Problem aquatic animals have been categorised according to their potential impact on the environment and appropriate restrictions and conditions apply to each category. These range from no stocking allowed into the inland waters of South Africa, to stocking restricted to “non-sensitive” areas or areas where introduced populations have already become established.

The Chinese carp have been categorised under the most severe conditions, while special policy guidelines have been prepared for the introductions of Grass carp. The NACC has determined that for Grass carp only sterile triploids can be stocked under permit in those waters where no suitable alternative indigenous species or other methods of aquatic weed control is feasible, while all possible measures have to be taken to prevent escapes of the fish into other waters.

The Institute for Water Quality Studies under the DWAF has developed the National Aquatic Ecosystem Biomonitoring Programme (NAEBP) to improve the monitoring of the environmental conditions in the aquatic ecosystem. It has become apparent that monitoring of the chemical and physical quality of water in isolation were not satisfactory indicators of aquatic ecosystem health or integrity. Biomonitoring has revealed that in some instances the habitat and water quality conditions were unimpaired but that the fish as well as invertebrate biotic integrity were seriously affected through the introduction of an exotic species. The relevance of the biomonitoring programme in this respect is that effects of introductions can be better monitored and understood and can be used as a basis to assess the risks that they may hold to other systems. Besides the impact of introduced species on biotic integrity, understanding of the effect of the introductions is a definite requirement to distinguish between their impact and the impacts of changes in the water quality and physical habitat.

The International Convention on Biodiversity was adopted in December 1993, and is probably the most relevant piece of international legislation. This Convention recognises the value of natural and domesticated biological diversity and acknowledges the issue of introduction and transfer of species.

Article 8 (g) states that:

"Each party … shall establish or maintain means to regulate, manage or control the risks associated with the use and release of living modified organisms resulting from biotechnology….

and

(h) prevent the introduction of, control or eradicate those alien species which threaten ecosystems, habitats or species”.

In addition the treaty provides for co-operation:

“in respect of areas beyond national jurisdiction and on other matters of mutual interest, for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity”.

The mechanisms of such co-operation have to be worked out by the states concerned.

SADC was set up by treaty in 1980, and has now 12 member countries. One of the main objectives of the Treaty is to ensure that development does not impair the diversity and richness of the region's natural resource base and the environment. The treaty provides for the achievement of:

“sustainable utilisation of natural resources and effective protection of the environment”,

for:

“co-operation in the area of natural resources and the environment”

and for implementation by sectoral commissions and technical advisory committees serviced by the secretariat.

SADC has established Commissions and Sector Co-ordinating Units to guide and co-ordinate regional policies and programmes in specific areas. The Food, Agriculture and Natural Resources (FANR) Sector occupies a focal position in the economic structure of SADC. In 1996 a proposal was made, and in principle approved, to restructure the FANR into seven sectors:

Agricultural Research;

Crop Production;

Livestock Production and Animal Disease Control;

Marine Fisheries;

Inland Fisheries;

Forestry;

Wildlife.

The Environment and Land Management sector (ELMS) would come out of FANR and become an independent sector, to have crosscutting mandate and to set environmental standards and guidelines for all SADC sectors and to monitor their observance.

The SADC overall policy objective for the FANR includes:

ensure the efficient and sustainable utilisation, effective management and conservation of natural resources;

incorporate environmental considerations in all policies and programmes, and to integrate the sustainable utilisation of natural resources with development needs; and

ensure the recognition of the value of natural resources so that they can contribute optimally to the welfare and development of all people in the region.

The Inland Fisheries Sector (IFS) emphasises its role in the maximisation of fish production, as stated in their objectives:

manage and utilise fish resources so as to maximise sustainable yields and promote regional self sufficiency in the supply of fish;

develop the fisheries industry on lakes, rivers, and flood plains and expand viable aquaculture schemes;

reduce losses and improve utilisation of under exploited species; and

improve the distribution and marketing of fish and fish products.

In 1995 the IFS stated that issues of biodiversity, pollution and environmental conservation must be addressed through bilateral and/or multilateral agreements between the SADC member states. It further stated that a very urgent and typical example of this is the issue of introduction of exotic species into regional waters.

The SADC Policy and Strategy for Sustainable Development emphasises the need to interpret environmental considerations into development planning and the need for popular participation in conservation. Promoting the sustainable management and utilisation of renewable resources is the responsibility of ELMS.

The SADC Water Sector was established in 1996 with the objective to specifically promote the sustainable and equitable development, utilisation and management of water resources. Functions of the Water Sector Unit include to facilitating integrated planning, developing and managing of water resources, and to facilitating the establishment of river basin institutions.

In 1995 the SADC countries signed a Protocol on the Shared Water Course Systems in the SADC region. This protocol was elaborated because the member countries recognised there were no regional conventions regulating common utilisation and management of resources of shared water systems. They were furthermore convinced of the need for co-ordination and environmentally sound development of the resources of shared watercourse systems in order to support sustainable socio economic development. Under this protocol the countries have agreed (among others):

to exchange available information and data regarding the hydrological, hydro-geological, water quality, meteorological and ecological condition of the shared water courses;

to take all measures necessary to prevent the introduction of alien aquatic species into a shared watercourse which may have detrimental effects on the ecosystem;

to establish appropriate institutions necessary for the effective implementation of the provisions of the protocol.

The main objectives of such institutions are:

to develop a monitoring policy for shared watercourse systems;

to promote the equitable utilisation of shared watercourse systems;

to formulate strategies for the development of shared water course systems;

to monitor the execution of integrated water resource development plans in shared water course systems.

Functions of the institution would be the harmonisation of national water resource policies and legislation, to monitor the compliance with water resource legislation, to recommend improvements, to promote measures for the protection of the environment and to prevent all forms of environmental degradation.

About 70 percent of the land area of the SADC is occupied by water course systems that are shared by two or more member states. The waters of these systems are increasingly a source of competition between the riparian countries. Since these international watercourse systems are common shared resources, they should be governed by the principles of international law where each of the states has the right to an equitable and reasonable share in the conservation, protection, management, allocation and utilisation. This promotes the establishment of regional co-operation among the riparian countries to facilitate the applications and the implementation of the rules on shared watercourse systems.

There are predominantly two types of institutional arrangements under which SADC counties co-operate in the development and management of water resources of shared water courses. These are:

A single co-ordinating institution where a body of technical experts is constituted and policy recommendations are left to ad hoc meetings of relevant ministers.

A dual level co-ordination which consists of a policy formulating body, such as a joint commission or permanent technical committee, with monitoring, advisory and approval powers over critical issues, and a body of technical experts to deal with the practical engineering and management aspects.

There are in total 21 agreements, bilateral or multilateral, between and among SADC countries on water management. One of these is the agreement signed in 1986 between South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique on the Limpopo Basin Permanent Technical Committee (LBPTC). This committee met in 1986 and met again in August 1995. A recent activity initiated by this committee is the Hydrologic Model for Upper and Middle Limpopo River. This activity aims to develop a model of the river system in order to meet future needs, and to improve the understanding of the hydrological system.

Under the agreement, the functions and duties of the LBPTC focus on the issues of water shortages and water uses, but may be expanded to any other relevant matters.

Water is an important natural resource, and due to increases in population and economic developments it has become under increasing strain in the form of water use and pollution from the various users. Point source pollution is controlled by emission standards, while nonpoint source pollution is far more difficult to control because of its highly variable and distributed nature. Control of the impact of nonpoint sources on water resources relies on control of the land use activity which generates the impact or the pollution.

The introduction of alien species can be seen as a form of pollution. However, unlike other forms of pollution, biological pollutants have the ability to reproduce and disperse in all directions; and when they do, they are virtually impossible to eradicate. This is in contrast to physical and chemical alterations which may be stopped at the point of origin. Besides a biological impact (competition with other species, predation, introductions of parasites, etc.) and physical impacts (alteration of the habitat), an introduced species may cause genetic pollution through hybridisation with related native species.

The impact of an introduced species depends on whether it will be able to establish a viable population, and on the interactions of that species with the environment. The Limpopo River System is a varied system which supplies many different niches. This is reflected in the number of exotic species that are now found in the river. So far eighteen alien species of fish have established populations in the Limpopo System, and these species represent a wide variety of environmental traits, ranging from cold water to typical tropical species.

Although some guidelines can be developed concerning the conditions under which a species may establish and have a negative environmental impact, it is difficult to apply these to a whole river system. River systems are diverse. Although a species may not thrive in a whole river system, it can find reaches that provide the right ecological conditions. This may well be in countries other than where it was first introduced. Procedures to evaluate the need and appropriateness of a certain introduction should, therefore, embrace all the countries that share a system.

Under the International Convention on Biodiversity countries have an obligation themselves to prevent introductions and to conserve biological diversity. The countries within SADC have further agreed to take all measures necessary to prevent the introduction of alien species into shared watercourses that may have a harmful effect, and to develop a monitoring policy for these systems.

The SADC countries clearly emphasise the importance of sustainable management of their natural resources, and mention the introduction of aquatic species as an important issue. The forum that would deal with this issue within SADC is less clearly identified. The IFS focuses mainly on increasing fish production and is in general less concerned with biodiversity and species introductions. It oversees one project on the protection of biodiversity in Lake Malawi/Niassa but states that introductions should be dealt with between countries sharing a certain system and not on a SADC level. The ELMS has a crosscutting mandate to set environmental standards and guidelines for all SADC sectors and is therefore probably the most appropriate sector to oversee all aspects of river basin management, including introductions of species. The SADC Protocol on Shared Water Course Systems sets the stage for the establishment of appropriate institutions for the management of these systems. The LBPTC was established to manage the issue of water shortages and water uses in the Limpopo. Although this committee has not been very active in the past, it is expected to become more involved in the future. Seen the tendency in the whole region to view water as a multiple function resource, the integration of disciplines other than strictly water use and abstraction into the LBPTC would be a logical step.

The consultation discussed the issue of how to regulate introductions. Possible options were:

ban all movement of aquatic species;

regulate at national level;

regulate as separate topic on a river system basis;

deal with overall management of river systems, including movement of species;

don't try to regulate anything.

The fourth option seems to be the most appropriate. However, in order to manage the issue of species introduction on a river basin basis requires changes in the present situation.

Figure 5: Distribution of private and communal dams near the crest between various river systems.

Most individual countries have a legal framework in place to control the introduction of fish into their country as well as to control transfers from one system to the other. However, the practice of authorising permits to import or translocate fish and the criteria used to authorise such activities are not well documented in all the countries. It is therefore difficult to assess to what extent introductions are controlled. There are also difficulties associated with enforcing legislation due to lack of resources to monitor fish farming and stocking activities in private waters. In this context, controlling the importation of a species into a country is easier from a legal point of view than controlling further distributions inside a country. This has lead to situations where once a species was introduced in a restricted area it has spread though private stocking activities into other river systems and other countries. A good example is the introduction of Oreochromis niloticus in Zimbabwe. A few farmers in the Zambezi System received the authorization to culture this species at their farms only. Because of the difficulty to control further distribution, this species has since spread to other farms, including farms situated in other water sheds. From there, it has escaped into natural waters and now O. niloticus is found throughout Zimbabwe and has been found in the Limpopo River from where it will enter the other countries sharing this system.

Stocking of private and public dams is a common activity in southern Africa. Many of these dams have been constructed near the water crest, and dams belonging to different river systems are located at close distance. These sometimes belong to the same farm (Figure 5). Movement of fish between these dams is very likely, and education and awareness may under those conditions be more effective than enforcement and policing.

Introduction of exotic aquatic organisms is a form of pollution that may have a negative environmental effect in the whole river system. It therefore has to be dealt with at that level.

Information exchange between countries as well as between the various national departments and organisations within countries is crucial for the establishment of rules and regulations to harmonise mechanisms to authorise introductions and to control the introductions of unwanted aquatic species.

Although this consultation only considered the introduction of aquatic species, and more particularly fish, it should form part of an overall management whereby land and water and the links between them, are managed in an integrated way on a catchment basis.

The consultation agreed on the following strategy to meet its conclusions:

Describe Limpopo Catchment from a cross-sectoral perspective (nationally).

Review nationally existing policies, legislation, regulation, data, monitoring and research programmes.

Identify stakeholders including related institutions and agencies.

Compile information from points 1–3.

Identify and establish sub-regional mechanism.

Establish linkages with regional institutions.

Inventory impacts/disturbances; habitat integrity assessment.

Design and implement monitoring programme, data bases, information exchange protocols and networking; harmonise policy and legislation through (sub-) regional mechanism.

Design and implement public awareness/education programme.

The following actions plan to implement the strategy were agreed upon:

1. Information compilation.

1.1 The following information will be compiled at SADC, sub-regional and national levels:

list of agencies and institutions involved in Limpopo Catchment management;

list and short description of relevant bibliographies and data bases;

indicative legislation and regulations regarding catchment management including, but not limited to, species introductions and translocations;

descriptions of present monitoring systems on the Limpopo System.

1.2 The following national contact individuals will co-ordinate information compilation:

Mr. Phera Ramoeli, SADC Water Sector Co-ordination Unit;

Mr. Trevor Mmopelwa, Botswana Fisheries Section;

Ms. Ana Paula Baloi, Mozambique Fisheries Research Institute;

Mr. Mick Angliss, South Africa Department of Environmental Affairs & Tourism;

Dr. Cecil Machena, Zimbabwe Department of National Parks & Wildlife Management.

1.3 ALCOM will be responsible for the following:

contacting sub-regional organisations for future co-ordination;

facilitate the exchange of information compiled by national contact persons;

continue to up-date data bases on Limpopo System.

2. Establish Catchment Committee.

2.1 Based on information from Action Plan 1, a suitable organisational structure in collaboration with contact persons and ALCOM.

3. Assessment and revision of existing policies and legislation

4. Standardisation of catchment management

N.B. Action Plans 1&2 are feasible immediately with existing resources, Plans 3&4 can be implemented only after the appropriate management structure has been identified or put in place.

The strategy for management of the Limpopo System is seen as a prototype for national and regional policies and legislation. Tested and proven mechanisms for sustainable watershed management of the Limpopo System should be adopted by member countries and SADC.