INDONESIAN FORESTRY SECTOR POLICIES AND FOREST RESOURCES

Forestry is the largest non-oil export-oriented sector in Indonesia. For over 30 years, the wood-processing industry has been supplied with low-cost raw materials from the natural forests. However, deforestation and forest degradation have led the Indonesian Government to turn to forest plantations as an alternative source of wood.

Indonesia: A large country with declining rich natural resources

Indonesia’s population of 210 million is unevenly distributed across 17 000 islands. About half of the people live on Java, which constitutes only 6.9 percent of the country’s total land area.

The natural forests of Indonesia are amongst the world’s most biologically diverse, and are characterized by three biogeographical zones:

The western islands of Sumatra, Java and Kalimantan with their extensive dipterocarp forests;

The intermediate zone comprising Sulawesi, Maluku and Nusa Tenggara with a variety of ebony, eucalypts and sandalwood (Santalum album or cendana) forests; and

Papua in the east with less diverse dipterocarp forests containing valuable Pometia and Agathis spp.

The three largest islands - Sumatra, Kalimantan and Papua - were until recently covered by extensive forests that comprised approximately 80 percent of the total natural forests. The forest in Kalimantan and Sumatra is rich in hardwood species (mainly dipterocarps) and accounts for 75 percent of the commercial log production. Fertile volcanic soils and teak (Tectona grandis) plantations characterize the Javanese landscape.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Outer Islands had a continuous forest cover while Java still possessed important forest areas. By 1950, Indonesia’s forest cover was estimated to be 162 million ha, or 84 percent of the total land area (Hannibal 1950, cited in FWI/GFM 2002).

Today, Indonesia has 120 million ha of forest land under permanent forest status (Ministry of Forestry Strategic Plan 2001-2005, cited in FWI/GFM 2002), although only 82 percent may actually be covered by forests (Fox et al. 2000, cited in FWI/GFM 2002). The deforestation rate continues to be as high as two million ha per annum (FWI/GFM 2002).

The role of the forestry sector in the economy

Indonesia shifted from being a producer and exporter of tropical hardwood logs during the 1970s, to a major producer and exporter of processed forest products by the late 1980s.[67] During the 1990s, it also became a major pulp producer.

Indonesian strategy for the forestry sector: export orientation

The forestry sector has a key role in Indonesia’s strategy for export-led development, which includes attempts to diversify exports beyond oil and gas (Madhur et al. 2000). The government has kept domestic wood prices much lower than international market prices. The vast forest resources were used for decades to attract foreign investment in wood processing and to boost economic development to generate revenues and employment, increase exports and improve the balance of payments. The comparative advantages of Indonesian wood-processing industries are competitive production costs due to low labour costs and cheap raw materials from the natural forests.

In the short term, the strategy has been successful in terms of forest product exports. However, it has also resulted in overcapacities in the processing sector and an inefficient industry that is unable to compete in the world market without subsidized wood prices. This has created an “irreversible” situation, in which the government has no choice but to continue supporting the industries by exploiting more natural forests (Karsenty and Piketty 1996).

Employment in wood processing

Data on employment are unreliable. Most employment is generated by the wood-processing sector. In the 1990s, formal employment in the primary wood-processing industries was about one million, and about 1.6 million including secondary processing. This corresponds to about two percent of the total national labour force (Fenton and Neilson 1998). Forests also provide jobs in the informal sector (such as fuelwood collection, handicraft and cottage industries, illegal logging). For example, each hectare of teak plantation in Java generates one to two jobs in the rural furniture industries, far more than plantation management itself.[68] Plantations raised for the capital-intensive pulp industries generate far fewer jobs (0.1 to 0.2/ha in plantation management including harvesting).

Forest product exports

During the mid 1990s, the forestry sector provided about 17 percent of the total value of all export commodities (Chaumont 1999). Total exports reached a value of US$8.5 billion, with US$3 billion being attributed to pulp and paper, and US$2.5 billion to plywood. Today, pulp and paper products represent about half of Indonesia’s forest product exports in value. The Indonesian pulp industry has five main operating mills. Between 1988 and 2002, the country’s pulp production capacity expanded from 0.6 to six million tonnes/year. The importance of plywood, on the other hand, has been declining. The Indonesian plywood industry comprises 115 companies. Eighty percent of the plywood production is exported. While total installed capacity is about 12.0 million m3/year, annual production currently reaches only about 50 percent of capacity.

Overharvesting of natural forest

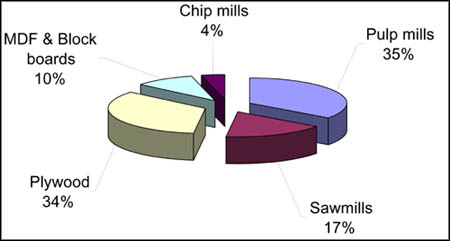

Annual raw material requirements by the wood-processing industries are about 48 million m3, with the pulp and plywood sectors taking the largest share (Figure 1). The officially recorded average annual log production has been around 22.5 million m3 over the last five years. In addition, an unrecorded amount of wood is unofficially processed by sawmills and a huge volume of logs is illegally smuggled across the country’s border.[69]

Source: Ministry of Forestry (2002, cited in IPB 2002). The figures exclude sawmills operating illegally.

Figure 1: Total wood-processing capacity

Current forest policies

Role of forest categories

According to the Basic Forestry Law (UUPK No. 5 1967, Article 4), about 50 percent of the total forest land has been declared as production forest, with the remainder set aside as protection and conservation forests. The New Basic Forestry Law[70] re-affirmed this classification and divides the forest land into five subcategories:

Production forest (29 percent of the forest land): Designated for timber production in which selective felling and clear-cutting followed by reforestation are permitted;

Limited production forest (18 percent of the forest land): Designated for erosion prevention and timber production in which selective cutting is permitted;

Conversion forest (seven percent of the forest land): Designated for conversion to agriculture such as oil-palm plantations or other uses;

Protection forest (27 percent of the forest land): Designated for soil and water conservation; no exploitation is permitted;

Conservation forest (parks and reservation forests, 19 percent of the forest land): Designated for nature and biodiversity conservation; no exploitation is permitted.

Logging is permitted within the production, limited production and conversion forests only. These three categories currently cover about 65 million ha, or 54 percent, of forest land (Ministry of Forestry Strategic Plan 2001-2005, cited in FWI/GFM 2002).

Current main policy objectives and natural forest harvesting issues

The government has five immediate programmes for forestry development for the period between 2001 and 2004, namely:

combating illegal logging;

controlling forest fires;

restructuring the forestry sector;

developing forest plantations and reforestation; and

decentralizing the forestry sector.

Numerous regulations imposed on the industry are intended to discourage excessive logging. However, most efforts seem to have little impact. Illegal logging and timber smuggling remain substantial problems. Since the start of the monetary and political crisis in 1997, illegal logging in protected forest areas has been widespread (FWI/GFM 2002). Environmental groups and some researchers are seeking to impose a moratorium on logging in all natural forests.

Forest management and decentralization

Indonesia is experiencing tremendous political changes. In 1999, a central government decision passed authority to district governments to allocate “forest harvest concessions” in areas classified as forest estates. District governments could issue small concessions of up to 100 ha for timber extraction in conversion forests or under certain conditions in production forests. Initial assessments showed that since authority has been decentralized, forest resources have declined at an unprecedented pace (McCarthy 2001a and 2001b; Kartawinata et al. 2001).

Governmental Regulation No. 33/1970 on Forest Planning set the criteria for determining state forest lands and their use. Logging activities (mainly by private forest concession holders or hak penguasan hutan (HPH)[71] were based on a Long-term Forest Management Plan (Rencana Karya Jangka Panjang), followed by Five-year Management Plans (Rencana Karya Lima Tahun) and Annual Activity Plans (Rencana Kerja Tahunan). The Ministry of Forestry (MoF) was responsible for assessing and approving the annual plans based on selective cutting and replanting procedures. Following the decentralization of authority, provincial and district forest agencies are responsible for preparing the various plans.

The rationale of forest plantation policies

According to the Basic Forestry Law, State Forest Areas that are not covered by forests are to be reforested and kept as permanent forests. To supplement the diminishing wood supply from natural forests, plantations were viewed as viable alternatives especially since timber production from one ha of a productive forest plantation was estimated to be equivalent to that from 20 ha of natural forest (Davis 1989). Hence, increasing the supply of plantation-grown timber for domestic wood processors would release more timber from the natural forests for export (Davis 1989) and reduce pressure on the remaining natural forests.

FOREST PLANTATION DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA

To facilitate analysing and discussing the impacts of incentives, plantation development in Indonesia can be divided into four periods:

Prior to 1980: Little interest in plantation development;

1980 to 1989: First efforts to develop industrial timber plantations, or hutan tanaman industri (HTI).[72] Investments in plantations remained insignificant as natural forest exploitation held priority;

1990 to 1997: Supported by a variety of incentives, development of fast-growing plantations by the pulp industries flourished; and

Since 1997: Investments in Indonesia have been affected by financial and political uncertainties.

Data on plantation areas for the years prior to 1980 were derived from the literature. From 1980 onwards, MoF data on annual plantings were used (Tables 1 and 2). However, it is widely accepted that the data are unreliable as they are based on information provided by private companies or state enterprises, and are usually unverified. Some plantations might not have been established at all or have virtually disappeared due to extremely high tree mortality rates. Thus, the figures used in the analysis must be considered as a theoretical maximum. Despite their weakness the available data indicate a trend, and help to illustrate how policies, laws and incentives have affected investor decisions.

Table 1: Industrial timber plantations by ownership type (ha)

|

|

1980-1989 |

1990-1997 |

1997-2001 |

Total |

|

Private |

102 080 |

741 339 |

263 279 |

1 106 697 |

|

Joint venture |

5 211 |

882 975 |

191 901 |

1 080 087 |

|

Total |

107 291 |

1 624 314 |

455 180 |

2 186 784 |

Table 2: Industrial timber plantations by purpose and transmigration (ha)

|

|

1980-1989 |

1990-1997 |

1997-2001 |

Total |

|

Pulpwood |

19 010 |

934 029 |

301 776 |

1 254 815 |

|

Non-pulpwood |

88 281 |

415 009 |

72 107 |

575 396 |

|

Transmigration |

0 |

275 276 |

81 297 |

356 573 |

|

Total |

107 291 |

1 624 314 |

455 180 |

2 186 784 |

Plantation categories

The term “plantation” is used in Indonesia for a variety of perennial crops (for example, rubber, cocoa and oil-palm). Including such estate crops, plantations cover a total area of about ten million ha. In the following discussion, reference is made only to forest plantations (excluding estate crops), which are divided into plantations in production forests and on critical lands.

Plantations in production forests

The two main plantation types in production forests are the HTIs on the Outer Islands and the plantations in Java. They are predominantly managed by the HPHs and forest plantation companies to supply wood to the pulp and paper industries, under the supervision of the Directorate of Management of Development of Plantation Forest. The HTI transmigration scheme also falls under this category. HTIs on the Outer Islands consist of fast-growing species (rotation lengths range from seven to 12 years). They have been established since 1985 and are mainly managed by private companies or through joint-venture arrangements with state forest enterprises, such as Inhutani. According to private company data, the HTIs on the Outer Islands cover 2.1 million ha, although the actual area reaches only between 0.9 and 1.2 million ha. The total productive area in Java is about one million ha. Java’s teak, pine or mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) plantations differ from those on the Outer Islands in the following characteristics:

Rotations range from 20 to 80 years;

Most were established in the early 1900s and management systems have changed little since then; and

A single state enterprise (Perum Perhutani) manages these plantations.

Afforestation or rehabilitation of critical lands: state initiatives

Regreening or afforestation on non-forest lands in Java and the Outer Islands is supervised by the Directorate of Reforestation and Rehabilitation of the MoF jointly with other Directorates (for example Directorate of Soil Conservation) or ministries (for example Ministry of Public Works). The Directorate of Reforestation and Rehabilitation is also responsible for reforestation of forest land on the Outer Islands. Characterized by poor survival rates, most of these plantations were established for protective purposes. The same directorate also promotes agroforestry and social forestry. In addition, the MoF has promoted community-based forest management and plantations through out-grower schemes on the Outer Islands.

Farm forestry and agroforestry: smallholders’ initiatives

Farm forestry and agroforestry are well developed in Indonesia, especially on Java where millions of farmers manage trees in their gardens and community forests. Farm forestry and agroforestry provide, though often unrecorded, wood supplies for domestic consumption and raw materials to small- and medium-scale enterprises. In Java, the main species planted are Paraserienthes falcataria (sengon), mahogany and teak.

Prior to 1980: Little interest in plantation development

Productive plantations

Prior to 1980, forest plantations (of mainly teak) were almost exclusively located in Java; rehabilitation planting took place either on Java or on the Outer Islands. Indonesia experienced several successive waves of reforestation programmes, but they have left few traces. Forest plantation development on the Outer Islands was not a priority.

Since 1895, large-scale industrial plantations have been established on Java (Fenton and Neilson 1998).[73] Teak, the principal species, was planted mainly in Central and East Java. By 1940, 266 000 ha had been planted with teak (Davis 1989). By 1980, the plantation area, including regreening and rehabilitation projects, had officially reached about 1.5 million ha, of which 800 000 ha[74] were industrial teak plantations and 280 000 ha were planted with pine.

Due to the land scarcity on Java, agricultural crops (for example, maize, pineapple or Calliandra calothyrsus during the first few years after planting) were integral features in forest plantation establishment. Until recently, Perum Perhutani also provided employment to landless farmers. It has its own budget, which is supplemented by funds made available through presidential instructions for social forestry and reforestation activities. Perum Perhutani had full control over the plantations until the 1997 monetary and political crisis.[75]

Large government rehabilitation programmes of the 1950s and 1960s

Prior to 1980, reforestation activities implemented by the government had little success. Most of the regreening and rehabilitation programmes were financed through special presidential instructions or projects funded by the Asian Development Bank.

Plantings (of mainly pines) in the 1950s and 1960s covered 400 000 ha in Sulawesi, 200 000 ha in Kalimantan, and up to 1.6 million ha in Sumatra. These figures do not account for losses incurred after the survival assessment (three years after planting) and are unreliable. By 1980, the survival rate at Year 9 was as low as six percent for regreening and 34 percent for reforestation (FAO 1980; cited in Davis 1989). These plantations might have been repeatedly burned or harvested and not replanted. Apparently, only about 67 000 ha established under the programmes have remained (Fenton and Neilson 1998).

Private plantations in logging concessions on the Outer Islands

Before 1969, commercial timber exploitation on the Outer Islands was insignificant. It was promoted by the initial Five-year Development Plans or Repelitas (1969/1970-1973/1974 and 1974/1975-1979/1980) and started to take off slowly in the early 1970s. The goal was to attract foreign and domestic investors. Logging concessions were leased initially for 20 years and could be extended to 35 years. Although regulations stipulated that the HPHs had to invest in forest plantations, most did not. In fact, only four percent of the companies followed the regulations (P.T. ITCI established 5 000 ha of plantations between 1974 and 1980 in Kalimantan); the government never prosecuted companies for non-compliance.

Lessons learned prior to 1980

As Indonesia’s natural forest resources were perceived to be indefinite, serious efforts in forest plantation establishment were lacking. Regulations did not control timber exploitation in natural forests effectively or trigger significant tree planting and forest rehabilitation. In fact, both were viewed as a formality or a target to be reached on paper only but not on the ground. They were phantom activities that generated income for the forest administration with few tangible accomplishments.

1980-1989: Plywood and natural forest concession development

Forest policy: Support of domestic wood processing

During the 1980s (the golden age of logging in Indonesia), HPHs enjoyed virtually unlimited freedom and extensive natural forest areas were degraded. At the same time, demand for industrial wood increased dramatically, induced by incentives from the government to develop domestic downstream wood processing. Roundwood exports were restricted to help the domestic industry compete with foreign wood processors (Decree MoF No. 317/Kpts/1980). Log exports were banned in 1985 and domestic wood prices were kept below world market prices to further assist the domestic industries, especially plywood producers.

Between 1980 and 1989, the number of plywood mills increased from 29 to 116 (Fenton and Neilson 1998). Within only one decade, Indonesia became the largest exporter of tropical timber products. Annual plywood production surged from one to nine million m3, which created a huge domestic demand for timber.

Main government decisions related to plantation development

To mitigate the negative impacts of timber exploitation and generate alternative timber supplies, the government set up a reforestation fund and promoted large-scale industrial timber and pulp plantations of fast-growing species.

The Reforestation Fund

Prior to 1980, HPHs did not rehabilitate the logged-over forests within their concessions as expected. The first attempt to address this situation was the introduction of the Danan Jaminan Reboisasi (DJR), or Reforestation Fund, by Presidential Decree No. 35 in 1980. HPHs were required to pay US$4/m3 for logs or US$0.5/m3 of chipwood extracted from forests in Kalimantan and Sumatra. The payments, which were in the form of a bond, went into the DJR to guarantee sustainable forest management by the HPHs. The DJR was to finance seeds and seedlings, land clearing, planting, weeding and inventory of logged-over forest stands. According to DJR regulations, HPHs could reclaim the bonds once they had fulfilled their obligations. Most concessionaires chose not to plant, but rather to write off their contributions to the DJR, which consequently grew considerably.

In 1984, the DJR was changed to Dana Reboisasi (DR), which could provide direct incentives for plantation development inside as well as outside concession areas. The government could use the bonds from non-performing HPHs for other purposes (Decree MoF No. 327/Kpts-II/1988). The DR became a royalty and was increased from US$4/m3 to US$7/m3 in 1989 to further support the development of HTIs.

The development of HTIs

In 1989, it was anticipated that wood demand would outstrip supply derived from natural forests. To counter the growing gap between supply and demand, the government planned the conversion of 4.4 million ha of unproductive land[76] to short-rotation plantations, to increase the plantation area from 1.6 million ha to six million ha by 2000.

Research

The government initiated research on fast-growing species to support the programme of rehabilitation of degraded lands and to create fuelwood plantations. Trials for pulpwood species were established on Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi and Nusa Tenggara. Research of private companies focused on Acacia mangium and eucalyptus species.

Limited impacts of the DJR and DR on the establishment of HTIs

Forest plantation development

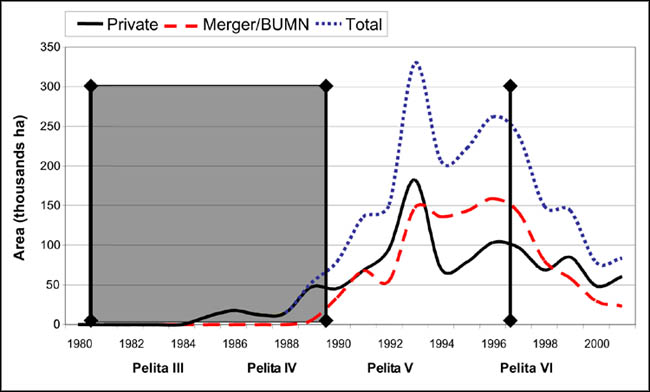

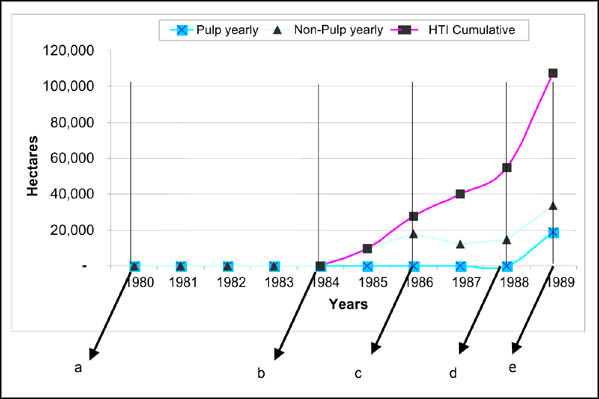

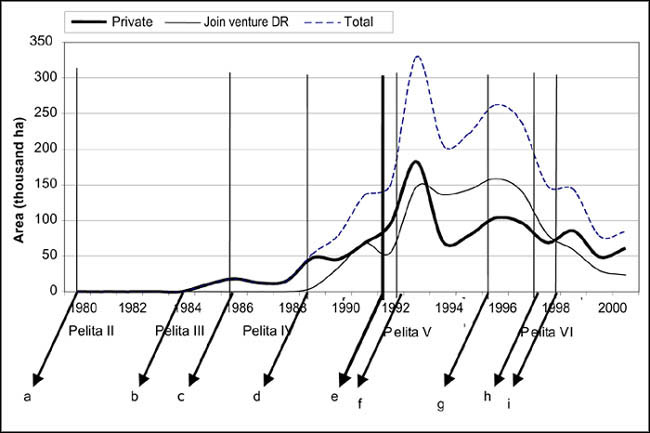

Industrial plantation development was marginal between 1980 and 1989 (Figure 2). The first HTIs on the Outer Islands were established for non-pulp uses[77] in 1985.[78] About 55 000 ha had been planted by 1988. During 1989, around 19 000 ha of pulp plantations were established. In total, between 1984 and 1989, 107 000 ha of productive plantations were reportedly established, compared to an annual target of 300 000 ha (Figure 3).[79] Following the changes since 1984, plantation development accelerated although it remained far behind the government’s expectations.

* BUMN: Badan Usaha Milik Negara, a state-owned company.

Figure 2: Area of plantations (1980-1989)

Natural forest logging: A disincentive for plantation development

The imposition of the log export ban discouraged plywood industries from investing in forest plantations. As large volumes of wood were available from the natural forests, investing in plantations was viewed as financially unattractive. By doing so, the government sent contradictory signals to industry with respect to forest plantation development and intentions to use the DJR for plantation development.

It was very naïve to rely on concessionaires’ goodwill for the rehabilitation of logged-over forests. In fact, concessionaires enjoyed enormous profits from exploiting natural forests while investing the proceeds outside the forestry sector. The interest rate for borrowing capital was about 20 percent in 1989, which was enough to discourage most investments in plantations.

Sources: MoF (1989); MoF (1989-2000); Directorate of the Management of Forest Plantation (2000/2001).

a. Presidential Decree 35/1980 on DJR

b. Repelita IV

1984-1989

c. Decree MoF 320/1986 about HTI and DR

d. Land access

facilitated by Decree MoF 327/1988 about incapable HPHs

e. Use of DR and

Decree 495/1989 about Ijin Permanfaatan Kayu (IPK) or Wood Utilization

Permit

Figure 3: HTI development for pulp and non-pulp uses

In the HPHs on the Outer Islands, 29 concessionaires and four state enterprises (Inhutani I, II and III and Perum Perhutani) were involved in HTIs between 1984 and 1989 (Davis 1989). The main species planted during that time were eucalyptus, Acacia mangium and meranti. (Shorea spp.). Due to a general lack of interest by the concessionaires, plantations were poorly maintained after the first three years, and were burned in many cases.

1990-1997: the expansion of pulp plantations

Context and main policies: oil-palm, pulp and paper development

During this period the government embarked on a development policy for oil-palm. Its intention was to ensure adequate supplies of cooking oil for domestic consumers, promote industrial development and boost exports. Plywood production remained stable[80]; the production and export of wooden components, furniture, and pulp and paper rose sharply.

The government continued to promote the establishment of large-scale industrial timber and pulp plantations. This was motivated by the anticipation of a raw material deficit by 2000, due to expanding domestic and export markets, and continuing deforestation and forest degradation. The target for production plantations by 2000 was five million ha.[81] The plantation development target for Repelita V (1989-1994) was 1.5 million ha and it was slightly reduced for Repelita VI (1994-1999) to 1.25 million ha.

Main incentives for industrial forest plantations

In 1990, the MoF decided to encourage private-sector investments in forest plantation development. Incentives targeted the Indonesian wood conglomerates, foreign investors, state enterprises and HPH holders. The main government schemes included:

promotion of HTI development;

joint ventures between private companies and state enterprises;

modification of the reforestation funds; and

HTI transmigration programme.

These schemes were inter-related. They provided HTI developers access to forest land, ready sources of capital and also cheap labour through the HTI transmigration scheme.

The HTI development policy

The official aim of promoting HTIs was to create wood resources on unproductive forest lands located in “productive forests”. However, in practice because of a lack of control and collusion, it triggered, in many places, clear-cutting of rich natural forests.

The HTI development policy was backed by a number of regulations throughout the 1990s. It was part of a development policy that recommended wood production within a 100-km radius around the pulp mills. In the early 1990s, prior to submitting proposals for investments in the pulp industry to the government, companies were required to demonstrate their capability to develop forest plantations by planting an area of 30 000 ha.[82] A number of plantations were established for this purpose between 1990 and 1992.

The main incentive was access to unproductive forests (Government Regulation No. 7/1990). After 20 years of logging (with frequent re-entries), many old forest areas were severely degraded. Some of these areas were thus legally converted into HTIs.

Joint ventures with state-owned companies

A state-owned forestry company, Badan Usaha Milik Negara (BUMN), and Inhutani on the Outer Islands, together with a private company, were made responsible for the management of logged-over forests from revoked HPH concessions. Through such ventures, land, access to reforestation funds and, in some cases, advantages associated with transmigration projects, were integral features of the partnership.

HTI transmigration scheme

The Ministries of Forestry and Transmigration jointly introduced the HTI transmigration scheme in 1990. One objective of this scheme was to control population growth in densely populated regions (Java and Bali). Another purpose was to provide cheap labour to a variety of companies active on the Outer Islands. The scheme started with the Ministerial Decree No. 341/Kpts-II/1992. The decree effectively reduced labour costs and indirectly subsidized plantation development as well as the expansion of oil-palm plantations.

Modifications to the reforestation fund

In 1990, the DR became a royalty and was increased from US$7 to US$10/m3 for logs and set at US$1.50/m3 for chipwood and logging waste (Presidential Decree No. 29/1990). In 1996, the “DR procedure for Government Capital Share and DR Loan for HTI Development” defined the DR-related financing schemes for joint ventures. Plantation development could be financed as follows: 14 percent Government Capital Share, 21 percent private capital share, 32.5 percent loan from reforestation funds and the remainder of 32.5 percent by commercial loans. As official figures for plantation establishment costs were usually inflated, capital provided through the financing schemes frequently exceeded actual costs.

The loans from the DR were interest-free for private enterprises willing to invest in plantations. They had to be repaid within seven years (the anticipated rotation length of Acacia mangium plantations). Disbursements were made annually or half yearly, based on assessments by state enterprises or consultants using a standard scoring system. The disbursements took into account the previous year’s performance, the annual working plan, and corrections related to the previous disbursements.

For “pure” private companies, 100 percent of the funds could come from commercial loans. The government also supported companies borrowing establishment capital from banks or other financial institutions (Barr 2000).

Other incentives

Research has focused mainly on fast-growing species for short-rotation fibre production (for example, Acacia mangium, Pinus merkusii, Paraserianthes falcataria and Gmelina arborea). In the drier areas, teak and mahogany were also tested. Besides the traditional research by government bodies, private companies (pulp and paper) tested fast-growing species. The main improvements were derived from Acacia mangium selection.[83]

The Wood Utilization Permit (IPK) was introduced, granting the right to use logging residues from conversion or degraded forests in HTI concessions, which were joint ventures with Inhutani.[84] Logs were supposed to be under 29 cm in diameter. The IPK allowed access to low-cost wood for pulp mills. Controls in the field were difficult and, in some cases, the IPK resulted in clear-cutting of rich natural forests. It encouraged plantation development to some extent, as it reduced the cost of clearing land.

Impacts of cross-sectoral policies

The 1991 tight money policy

In early 1991, a rumour about the imminent devaluation of the rupiah increased the risk of a double-digit inflation and an eventual devaluation. Faced by pressure to sell the rupiah, the government initiated a tight money policy (TMP), or the Sumarlin Shock II. The TMP restricted offshore loans and limited mega-projects. As a result, several plantation projects were cancelled after October 1991.[85]

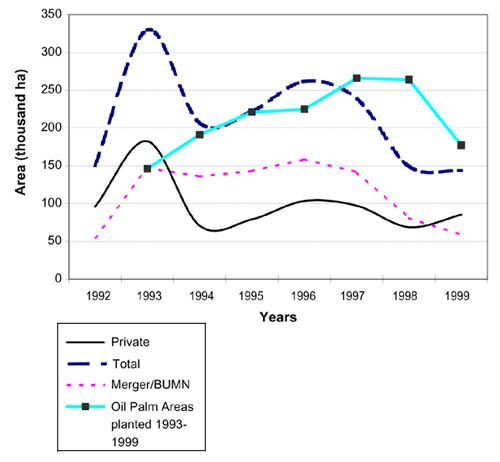

The oil-palm development policy

From 1994 to 1997, the oil-palm boom had a direct negative impact on forest plantation development (Figure 4). During Repelita V (1990-1994), the government gave high priority to the agricultural development of provinces outside of Java. This was successful for oil-palm plantation establishment, which attracted many investors.

Figure 4: Competition between forest and oil-palm plantations

The oil-palm sector enjoyed a variety of government incentives: government-funded infrastructure, easy land access and acquisition, credit for investors, subsidized interest rates, cheap labour as a result of transmigration projects, and policies conducive for attracting foreign capital (Potter and Lee 1998). These incentives accelerated the conversion of natural forests. Some companies also applied for oil-palm concessions in Kalimantan or Papua to harvest timber during land clearing. Such activities sometimes extended into production forests and even protected forest areas (Casson 2000).

The area of oil palm plantations reached 1.1 million ha in 1999 (Departemen Kehutanan dan Perkebunan, cited in Casson 2000). This expansion occurred mainly in Sumatra, and to a lesser extent in Kalimantan.

In some cases, oil-palm development competed directly with forest plantation development for land, as witnessed in the P.T. Finnantara (Stora-Enso) concession in West Kalimantan, and for financial resources, as in the case of the Sinar Mas (Indah Kiat-WKS) and APRIL (RAPP) groups.

Impacts of incentives on plantation development

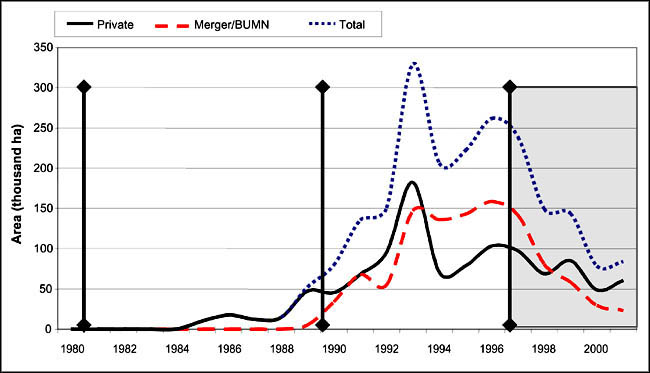

During Repelita V (1990-1994), 900 000 ha of large-scale plantations were planted, amounting to 60 percent of the 1.5 million ha target. Overall, it was a period of rapid HTI expansion, although the annual target of 300 000 ha planted was only met in one year, that is 1993 (Figure 5).

From 1990 to 1993, “pure” private companies invested considerably in forest plantations to persuade the government to approve their pulp mill development plans. These plantations achieved a record growth of 170 000 ha in 1993. In 1994, most of the requests for pulp mills were granted. The joint-venture investments in forest plantations were high from 1992 to 1997. They peaked in 1992 when the HTI transmigration programme was initiated and in 1996 when access to the reforestation funds was facilitated by regulation MoF 375/Kpts/1996. The cartels, which held the HPHs-HTIs, however, soon turned to new investments, such as oil-palm plantations. As a result, investments in private forest plantations decreased drastically and annual plantation establishment has since then been below 100 000 ha.

Impact of HTI transmigration scheme

The HTI transmigration programme accounted for 20 percent of the reforestation fund disbursement. However, the HPH companies participating in the programme were rather inexperienced in forest plantation development. In many cases, the plantations were unsuccessful. Some were located in remote areas too far from industries. The most successful ones were associated with large HTI projects, such as the joint venture with Barito Pacific in South Sumatra.

Impact on small-scale HTIs, smallholders and communities

Small-scale concession holders had no access to the reforestation funds. Small-scale plantations have generally remained undeveloped despite MoF Decree No. 69/Kpts-II/1995 that obliges HTIs to involve communities in forest plantations. The decree does not specify how management of the plantations and their benefits are to be shared. Few HTI-concession holders paid attention to the welfare of local communities. P.T. Finnantara was amongst the few that tried establishing partnerships between communities/smallholders and large companies during Repelita VI (1994-1999). This attitude changed only with the increase in social disputes over land rights and forest fires.

Sources: MoF (1989); MoF (1989-2000); Directorate of the Management of Forest Plantation (2000/2001)

a: Presidential Decree 35/1980 (bond for HPH rehabilitation)

b: Repelita IV (1984-1989), political decision to develop industrial plantations

c: Some impact due to Decree MoF 320/1986 (HTI and reforestation funds)

d: Land access facilitated by Decree MoF 327/1988 about non-performing HPHs and Decree MoF 495/1989 (IPK) on easier access to reforestation funds; impact on joint ventures

e: Beginning of the TMP; negative impact on pure private plantations

f: HTI transmigration scheme launched in 1992: impact on joint ventures

g: Reforestation fund regulation (MoF 375/Kpts/1996): impact on joint ventures

h: 1997 economic crisis; less HTI transmigration, extensive forest fires, decrease in joint ventures

i: End of reforestation funds; drastic decline in joint ventures

Figure 5: Annual plantation establishment

Misuse of the reforestation fund

From 1990 to 1994, access to land and capital were the major incentives for forest plantation development. However, procedures to access the reforestation fund were not transparent. Funds were mainly available to a select group of people with close ties to the political elite. Many investors sought to maximize their short-term profits and neglected the long-term future of their plantations. Most HPH holders were involved in HTIs only to extend their logging permits. In many cases, the MoF did not enforce its regulations and allowed companies to establish HTIs in rich natural forests. The state forest enterprises themselves were not always eager to develop HTIs, as logging in natural forests was considerably more profitable.

Few companies used the reforestation fund as stipulated despite guidelines to prevent misuse. Companies had to formulate proposals requesting the reforestation funds for HTIs. Once the proposals were approved and funds disbursed, companies established plantations on smaller areas than actually declared.[86] There was a lack of independent monitoring and assessments, the main weakness of the system. Although the MoF was to conduct field assessments, it had limited resources for field inspections. In addition, information was not shared by the various divisions in charge, which exacerbated comparisons between field and disbursement data (Ernst and Young 1999).

Some companies have also been suspected of deliberately setting fire to plantations, especially if plantations were unsuccessful. This was one way to avoid repaying loans at the end of the seven-year term. Other companies minimized costs by using poor planting techniques, such as direct seeding, to divert funds to other activities.

The government itself used a large proportion of the reforestation fund for non-forest related projects. Between 1993 and 1998, US$5.25 billion was lost from the reforestation fund, due to poor enforcement (Down to Earth 2000). The reforestation fund disbursed US$950 million between 1990 and 1997 for forest plantation development (Kamil 2001). This should have been sufficient for establishing approximately five million ha, compared to the 0.9 million ha that were actually established using the fund.[87]

Lessons learnt and discussions

The area under forest plantations increased more slowly than planned by the government. However, plantation development accelerated between 1990 and 1997. About 1.6 million ha of plantations were established, although doubts about the accuracy of this figure remain.

Acacia mangium was the predominant species. Direct incentives assisted joint-venture efforts to establish 0.9 million ha. Private companies established another 0.7 million ha without any direct incentives. This suggests that direct incentives are not necessarily needed to stimulate investments in short-rotation plantations.

The misuse of the reforestation fund was not surprising, considering the political and economic context during the Suharto era. With poor governance and control, channelling direct payments through the reforestation fund proved to be virtually impossible. The lack of independence and integrity of consultants evaluating the results, and the lack of reliable data and maps were key factors that led to the improper use of the funds.

Incentives for forest plantation development cannot be seen in isolation from other government decisions. The TMP and the oil-palm development policy had a significant influence on the willingness to invest in plantation development after 1992. Investors preferred commodities, such as oil-palm, with more rapid returns. In addition, the re-organization of the MoF and the appointment of a new Minister of Forestry in 1994 also delayed new forest plantation developments.

1998-2002: The forest sector during the Indonesian crisis

The new political context and its impact on forest plantation development

General investment climate: lack of confidence

The 1998 economic crisis and subsequent political changes in Indonesia kept investors away from Indonesia. Political instability on the Outer Islands and conflicts with local communities led to the failure of the transmigration programmes. The rapid development of the wood-processing sector of the previous decades resulted in an industrial overcapacity that could not be met by the annual wood production, and illegal logging filled the gap. Poor law enforcement reinforced the impact of the crisis on the forest plantation sector. The government did not even issue specific targets for HTI development in Repelita VII (1999/2000-2004/2005). Plywood exports fell from eight million m3 in 1998 to 6.3 million m3 in 2001.

The decentralization process encourages logging

The regional autonomy policy came into effect in 2001, allowing regional authorities to take charge of forest concession licensing.[88] The provincial governors were authorized to issue forest concession permits for up to 100 000 ha.[89] Small-scale logging concessions under 100 ha could be issued at the district level. Such arrangements caused considerable confusion since regional policies often differed from that of the central government. For example, the central government revoked a number of HPHs but local governments assigned new, smaller concessions. The outcome encouraged logging, legalized part of the ongoing illegal logging and gave industry access to wood resources at cheap prices.

Incentives and disincentives: unclear messages to investors

The domestic wood price

Two sets of measures were taken to bring domestic wood prices in line with world market prices, namely:

A Letter of Intent (LOI) between the Indonesian Government and the International Monetary Fund, which paved the way for trade liberalization in the wood industry (the LOI revoked the ban on log exports)[90]; and

Increased levies for wood from natural forests.

Logging companies operating legally must comply with

replanting regulations and pay up to

13 forestry-related fees. Fees total

about US$35/m3 of logs harvested from designated forest areas. Recent

policy subjects logs to a ten-percent value added tax (VAT). However, illegal

logging has upset these measures and no clear signals have been sent to

investors. In fact, the government recently re-imposed the log export

ban.[91]

The suspension of reforestation fund disbursements

This period was characterized by a drastic reduction in the contributions from the reforestation fund. Bowing to international pressures, the management of the reforestation fund was transferred from the MoF to the Ministry of Finance in 1998, and an audit of the reforestation fund was conducted in 1999 (Ernst and Young 1999). The audit results have not been widely publicized. The reforestation fund was frozen from 1998 to 2002.

In 2002, a decision was made to resume using the reforestation fund, which stood at that time at around Rp7.8 trillion. The head of the district (Bupati) is to conduct field monitoring to control the use of the fund. The allocation system has remained unchanged, and the fund is to be managed by the MoF headquarters and the Bupati.[92]

A new trend: incentives to attract smallholders and communities

Policy for community involvement in plantations

MoF Decree No. 69/Kpts-II/1995 requires HPHs and HTIs to involve communities in forest development. Community involvement in forest management is also stressed in the Basic Forestry Law (No. 4/1999). Other decrees emphasize the rights of local communities and their access to credit. In addition, forest exploitation was opened to cooperatives soon after the departure of Suharto as president.

Private initiatives of community involvement

Indonesia’s pulp producers increasingly require wood from plantations. However, access to land and wood supplies were constrained due to land disputes between companies and local communities. As a result, some companies are testing new forms of partnerships with individuals or communities through cooperatives. P.T. Musi Hutan Persada, an HTI in South Sumatra linked to the Barito Pacific group, provides three types of incentives to encourage villagers to plant trees on community lands:

wages for labour during the planting phase;

management fees paid to local community organizations; and

production fees after harvesting.

On private land, other incentives include:

material inputs and technical advice from the company;

financial support for owners; and

sharing of revenues with landowners receiving 40 percent and the company 60 percent.

All other major HTI companies, such as Finnantara Intiga in West Kalimantan, RGM and P.T. Araba Abadi in Riau, and P.T. Wirakarya Sakti in Jambi, are offering similar incentives to communities and small-scale landowners.[93] However, these attempts are still in their infancy: In 2001, the total cumulative area of such partnerships initiated by large pulp companies covered only about 30 000 ha.

Impacts of the crisis: fewer incentives, less plantations

Annual forest plantation development decreased from 230 000 ha in 1997 to 78 000 ha in 2000, most being private plantations (Figure 6). This largely reflected the termination of the transmigration projects, loss of contributions from the reforestation fund, uncertain land tenure and the increasing attractiveness of oil-palm. Private investments were less affected than joint ventures from these developments.

Although wood production derived from plantations is not sufficient to meet the needs of the pulp industry, it is slowly increasing.[94] Most large pulp producers are developing plantations to supply their mills despite considerable problems with land access and tenure, and escalating land disputes. The quality of plantations is improving, as the industry increasingly relies on plantation wood.

Figure 6: Annual plantation development (1998-2002)

Lessons learnt and discussions

Concession holders have learned that their authoritarian relationship with local people poses a risk for forest plantation development. The rapid expansion of plantations in the early to mid-1990s, during which large conglomerates benefited from the incentives, was unsustainable. The most equitable incentives since the late 1990s have been the efforts to support community forestry. Within the current policy context of Indonesia, plantation developers have realized that they must also invest heavily in infrastructure and social relationships.

Today, the key problems of the concessionaires and investors are poor law enforcement and security of their plantations. Developing partnerships and positive relations with communities is a long-term investment - much longer than a rotation of Acacia mangium. The duration of concession rights for HTIs follows that of HPHs. It is most suited for operators whose only interest is in logging but not for companies that invest heavily in forest management prior to harvesting.

OBSERVATIONS AND FINDINGS

Links between policies and their impacts on plantation development are not straightforward. In fact, declarations, laws and guidelines are only indicators of the decision-making processes, which are affected by a variety of factors that cannot be completely identified. Policies also remain ineffectual if they are not implemented.

A major factor that cannot be directly observed is the political-economic context in which policy-making processes are taking place. Since the 1970s under the New Order Regime, the forests and non-renewable resources have been overexploited with a small elite profiting most (Dauvergne 1994; Durand 1994; Barr 2000).

While the effects of policies take time to become apparent, other decisions made by the government and other stakeholders also affect the magnitude of the potential impacts. It is thus difficult to identify the exact cause-and-effect relationships or to interpret the impacts.

Continuing deforestation in Indonesia

Even though most of the forest plantations were established during the 1990s, deforestation continued largely because of poor governance, given the political and economic situation in Indonesia (Barr 2000). The government approved the development of too many pulp mills. The excessive installed capacity necessitated the use of mixed dipterocarps as raw material. In many places, the pulp producers were enabled to establish plantations in rich natural forests without any sanctions. The HTI policy to rehabilitate overharvested production forests was actually being used to degrade natural forests.

Provision of cheap raw material for the wood industry

The policy of providing cheap raw material for the wood processing industry has proven to be a major disincentive for forest plantation investors. Wood stumpage prices dropped and developing plantations became financially unattractive. Measures to increase wood stumpage prices and reduce access to natural forest resources would likely be a more efficient way to promote forest plantation development.

Incentives, market prospects and land security

In the early 1990s, forest plantations mushroomed in response to the perception of an ever-increasing demand in Asia for pulp and paper products, and government incentives. The requirement for an industrial plantation to be established before being granted a permit to set up a processing plant also triggered private and joint-venture initiatives in tree planting.

In fact, the boom-and-bust cycle was similar to developments in the plywood sector during the 1980s when the installed processing capacity outpaced the wood output from Indonesia’s forests. The plywood industry continued to expand without proper investment in sustainable forest management and plantation development, eventually leading to the problems the plywood industry and the entire forestry sector face today.

Reforestation fund irregularities

According to the most recent assessment by the MoF (based on company declarations), the reforestation fund has helped to establish 1.2 million ha of joint-venture plantations, an area that is only one-fifth of what it should be if the fund had been used properly. Even then, in some cases, the area established was exaggerated or inferior planting stock and techniques were used to minimize the costs. Many incentives had been abused and this was largely due to a lack of control by independent bodies.[95]

Private plantations established without assistance from the reforestation fund were doing as well as joint-venture establishments supported by the fund. This suggests that the reforestation fund or direct subsidies may not be needed for the development of plantations that rely on fast-growing species.

Cross-sectoral impacts

Developments in other sectors have also had a major impact on forestry development in Indonesia. For instance, the 1991-1994 TMP or the 1994-1998 boom of oil-palm plantations significantly slowed down the HTI development. Land-use conflicts between different sectors also posed problems for plantations. In some cases, concessions for agricultural development in areas around paper mills were issued, such as in Riau, or they overlapped with forest plantation concessions, such as in West Kalimantan. In Riau, two huge complexes of pulp and paper industries were established in the same area, increasing wood-supply problems and land-use pressures.

Non-involvement of the local population

Rapid plantation development during the early 1990s rarely considered the interests of the local population. It was thus unsustainable and often created more long-term problems. It is now generally accepted that the involvement of local communities is necessary to ensure the success of plantations.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Direct subsidies should be reserved for long-term investments

Subsidizing short-rotation plantations is usually neither necessary nor useful. Instead incentives should be provided for long-term rotation plantations that have the potential of producing more raw materials to supply future timber and pulp industries. These plantations also provide more environmental services.

Land-use planning, land-tenure resolution, social forestry and social welfare are issues that must be addressed by the government. The private sector is not in a position to deal with such issues effectively. Government support is also needed to encourage private investments in long-term forestry projects.

Control of pulp and paper mill supplies should be tightened

Deforestation in Indonesia is currently out of control due to:

illegal logging and poor governance;

low salaries of MoF employees;

conflicts of interests amongst various ministries; and

other problems (for example, debts, poverty, transition to decentralized authorities, extortion, corruption).

The government should strongly discourage pulp industries from using mixed-tropical hardwoods, but persuade them instead to utilize plantation-grown or imported wood. Eventually, the Indonesian wood industry will have to rely on sources other than the natural forests to meet raw material requirements. Wood prices at the mill gate need to be on par with world market prices. Currently, the main disincentive for plantation establishment is the low stumpage price. Past experience has shown that direct incentives for forest plantation development (such as soft-loans, grants) are likely to be abused. An efficient stimulus would be to increase the mill gate price for wood as early as possible.

Capacity of state forestry officers should be strengthened

Indonesia needs to create a new generation of state forestry officers who are dedicated to sustainable forest management. Foresters need to be well paid and equipped in order to be independent of the industry and concessionaires whom they are to monitor and control. To be totally transparent, MoF employees and NGOs should jointly monitor and control natural forest management, plantation developments and the wood-processing sector.

Taken, together, these measures could be more effective for forest plantation establishment in Indonesia than the provision of direct incentives.

LITERATURE CITED

Barr, M.C. 2000. Profits on paper: fiber, finance and debt in Indonesia’s pulp and paper industry. In Banking on sustainability: a critical assessment of structural adjustment in Indonesia’s forest and estate crop industries. Bogor, Indonesia, Center for International Forestry Research and WWW-International.

Casson, A. 2000. The hesitant boom: Indonesia’s oil palm sub-sector in an era of economic crisis and political change. Occasional Paper 29. Bogor, Indonesia, Center for International Forestry Research.

Chaumont, A. 1999. La filière bois en Indonesie poste d’expansion économique de Jakarta (mimeo, unpublished).

Dauvergne, P. 1994. The politics of deforestation in Indonesia. Pacific Affairs, 66: 497-578.

Davis, C.W. 1989. Outlook and prospects for Indonesia’s forest plantations. Indonesia. Ministry of Forestry. Directorate General of Forest Utilization Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Series Indonesia. UTF/INS/065/INS: Forestry Studies; Field Documents No. 1-3.

Down to Earth. 2000. Spotlight on Indonesia’s forests. Down to Earth No. 44. http://dte.gn.apc.org/44for.htm.

Durand, F. 1994. Les forêts en Asie du Sud-Est. Recul et exploitation. Le cas de l’Indonesie. (Forest in Southeast Asia; recession and exploitation: the Indonesian case.) Collection Recherches Asiatiques, l’Harmattan, Paris.

Ernst & Young. 1999. Special audit of the reforestation fund, final report. Report to the Ministry of Finance. Jakarta.

Fauvreau, S. & Laburthe, P. 2002 The teak market chain in Central Java. CIRAD-CIFOR field survey. Bogor, Indonesia, Center for International Forestry Research.

Fenton, R. & Neilson, D.A. 1998. The forest industry sectors of Malaysia and Indonesia. Rotorua, New Zealand: Dana Publishing.

FWI/GFM. 2002. The state of the forest: Indonesia. Bogor, Indonesia, Forest Watch Indonesia, and Washington, DC, Global Forest Watch.

Iljas, A. 1998. The transmission mechanism of monetary policy in Indonesia. Policy Paper No. 3. Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements. pp. 105-126.

IPB. 2002. Issue paper development of production forest resources - suggestions on policies for the Ministry of Forestry. Bogor, Institut Pertanian Bogor.

Kamil, T. 2001. Dana Reboisasi digunakan untuk anggaran. Tempo, No. 28, June: 3.

Karsenty, A. & Piketty, M.G. 1996. Strategies d’industrialisation fondee sur la resource forestière et irreversabilites - les limites de l’experience indonesienne. Revue Tiers Monde, No. 146, April-June: 431-451.

Kartawinata, K., Riswan, S., Gintings, A.N. & Puspitojati, T. 2001. An overview of post-extraction secondary forests in Indonesia. Journal of Tropical Forest Science, 13 (4): 621-638.

Madhur, G., Lele, Hyde W., Kartodihardjo Hariadi, Khan, A. & Rana Saeed. 2000. The challenges of World Bank involvement in forests: an evaluation of Indonesia’s forests and World Bank Assistance. Washington, DC, World Bank.

McCarthy, J.F. 2001a. Decentralisation and forest management in Kapuas district, Central Kalimantan. Bogor, Indonesia, CIFOR.

McCarthy, J.F. 2001b. Decentralisation, local communities and forest management in Barito Selatan district, Central Kalimantan. Bogor, Indonesia, Center for International Forestry Research.

MoF. 1989. Forestry studies. Jakarta, Ministry of Forestry.

MoF. 1989-2000. Forestry statistics of Indonesia. Jakarta, Ministry of Forestry.

Nawir, A.A., Santosa, L. & Mudhofar, I. 2002. Towards mutually-beneficial partnership in outgrower schemes: lessons learnt from Indonesia. Bogor, Indonesia, Center for International Forestry Research.

Potter, L. & Lee, J. 1998. Tree planting in Indonesia: trends, impacts and directions. Occasional Paper No. 18. Bogor, Indonesia, Center for International Forestry Research.

Watanabe, S. 1998. Evolution of the crisis in Indonesia. International University of Japan http://www.iuj.ac.jp/faculty/watanabe/Works/Indonesia/PartI.htm

|

[65] Scientist, Center for

International Forestry Research, Bogor, Indonesia. [66] Regional Coordinator of Forest Plantation Development, Ministry of Forestry, Jakarta, Indonesia. [67] In 1988, Indonesia became the leading exporter of tropical plywood (Madhur et al. 2000). [68] According to an estimated 5 m3/ha/year and results from Fauvreau and Laburthe (2002). [69] Official trade data show around 250 000 m3 of logs are exported annually; the volume of logs smuggled is unknown but could be as high as ten million m3/year. [70] Article 6 Undang-Undang tentang Kehutanan No/4:1999. [71] HPH refers to a concession right for productive natural forest harvesting. [72] Defined by Decree 320/Kpts-II 1986, the purpose of the HTI was to enhance the output of unproductive forest land and to produce raw material for the industries. HTI operators include HPHs, provincial forestry offices, state enterprises and private companies that are regarded and classified as able and appointed by the MoF. [73] Teak was planted in West and East Nusa Tenggara as well. [74] According to Perum Perhutani, the total area of teak plantations is 1.09 million ha; 0.8 million ha refers to the area of productive teak plantation. [75] Today, rotations are shorter and teak plantations suffer from illegal logging. [76] Unproductive lands were defined as Imperata cylindrica grasslands and shrub forests within production forests. [77] This excludes enrichment planting on the Outer Islands. Enrichment plantations refer to plantations of wild seedlings in areas where natural generation has failed. During this period, an average of 5 000 ha/year of enrichment plantations were established. However, survival rates were poorly recorded and it appears that many plantations exist on paper only. [78] From 1985 to 1990, some plantations were established in Java to supply small-scale enterprises. For example, 35 000 ha were set up to provide material for a pulp mill at Cilacap. Other industrial plantation projects planted Paraserianthes falcataria and eucalyptus. [79] The target of Repelita IV (1984-1989) was set at 1.5 million ha over five years. [80] Annual plywood production was 8-9 million m3; it peaked in 1992 and 1993 at about ten million m3. [81] Investment needed for achieving the target of some five million ha of productive forest plantations outside Java was estimated to be up to US$5 billion (Davis 1989). The target of 25 million ha of plantations, including rehabilitation and protection plantations, was set for 2000. [82] Christian Cossalter, CIFOR, personal communication. [83] Before selection, the mean annual increment (MAI) was on average around 15 m3/ha. Improved varieties reached more than 30 m3/ha. Rotation declined from 12 to seven years. [84] Wood Utilization Permit (IPK), MoF Decree No. 178/Kpts-II/1996. [85] For example, P.T. Rimbabelantara Pertiwi (C. Cossalter personal communication). See also Iljas (1998) and Watanabe (1998). [86] For example, P.T. Musi Hutan Persada claimed 200 000 ha were planted, while independent estimates are in the order of only 100 000 ha. [87] Another evaluation (up to May 2002) found that 1.2 million ha were established under joint-venture arrangements (MoF Directorate General of BPK - Ministry of Forestry 2002). [88] MoF Decree No. 05.1/Kpts-II/2000 about Forest Utilization Permit and Forest Product Harvesting Permit in the Production Forest. [89] Government Regulation No. 6/1999 about Forest Utilization and Forest Product Harvesting Permit in the Production Forest. [90] MoF Decree No. 510/1998 - Allow small log export. [91] MoF Decree No. 1132/Kpts-II/2001 - Ban of export logs/raw material for chips. [92] PP 35/2002 on reforestation fund. [93] For more information about Finnantara and the WKS outgrower scheme, see Nawir et al. (2002). [94] For example, Riau Andalan Pulp and Paper claims that supply from Acacia mangium plantations contributed up to 30 percent of their raw material needs in 2002 and is expected to reach 100 percent by 2008. [95] In late 2002, the Ministry of Forestry revoked the timber concessions of 15 companies due to their failure to develop required industrial timber plantations. Companies had been awarded a total area of 989 079 ha, but developed only 188 950 ha, despite the government providing them with loans for the purpose (Jakarta Post, 12 November 2002). |