INTRODUCTION

Geographic and economic backgrounds

New Zealand comprises two main islands (North Island and South Island) and several small islands, totalling 27.1 million ha in area. About 25 percent of the land area is less than 200 metres above sea level; steep hills and mountain ranges that approach 3 754 metres often form a backdrop to this low-lying land. New Zealand experiences a maritime, temperate and windy climate. It has a population of 3.8 million people. The economy is based largely on export-oriented primary production, with agricultural products accounting for about 35 percent of total overseas trade (by value). Some economic indicators of New Zealand are presented in Table 1.

Before initial Mâori (Polynesian) settlement in New Zealand about 800 years ago, most areas below the natural treeline were forested. Over 100 natural forest types covered around 85 percent of the country. Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries in particular, large areas of forest were burnt as the population expanded. In 1840, when the Mâori population was about 115 000 and European settlers numbered approximately 2 000, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed between the British Crown and Mâori chiefs to record the consent of the Mâori to New Zealand becoming a British colony.

European settlement commenced in earnest from this time, when indigenous forests covered about 53 percent of the land area. The European settlers and their descendants saw forests as both an obstacle to agriculture and an inexhaustible source of timber. Pasture increased from less than 70 000 ha in 1861 to 4.5 million ha in 1901. By 1920, most of the current 11.9 million ha of agricultural land had been cleared. This was the primary cause of the decrease in natural forest cover to the current 6.3 million ha or 23 percent of New Zealand’s land area (Ministry for the Environment 1997).

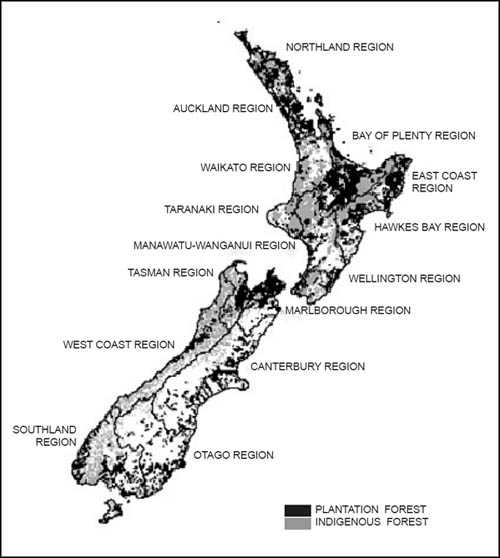

Table 2 details current land uses, while Figure 1 shows the distribution of plantation and indigenous forests. Approximately 16.8 million ha of the total land area is under private ownership and 10.3 million ha belong to the government.

Table 1: New Zealand economic indicators (year ended 31 March 2001)

|

Population density (people/km2) |

14.16 |

|

GDP (NZ$ million)* |

112 316 |

|

GDP per capita (NZ$) |

29 271 |

|

Forest industry contribution to GDP (%) |

4.0 |

|

Total NZ merchandise trade - re-exports (NZ$ million)** |

30 793 |

|

Forest industry contribution to total NZ merchandise trade by value (%) |

11.5 |

|

Net international debt (NZ$ billion) |

84.3 |

|

Annual percentage change in GDP |

+2.5 |

|

Inflation (%) |

+3.0 |

|

Labour force (million) |

1.915 |

|

Forest industry employment as percentage of labour force |

1.3 |

|

Unemployment rate (percentage of labour force) |

5.2 |

Sources: Statistics New Zealand; Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry

* GDP = Gross domestic product; on 1 August 2002, NZ$1.00 = US$0.47.

** Year ended June 2001 (provisional).

Table 2: Current land uses in New Zealand

|

Land use |

Area (million ha) |

Percentage of total area |

|

Indigenous forest |

6.3 |

23.2 |

|

Shrubland |

2.7 |

10.0 |

|

Plantation forest |

1.8 |

6.6 |

|

Pastoral, horticulture & arable |

11.9 |

43.9 |

|

Tussock grassland |

2.0 |

7.4 |

|

Other land* |

2.4 |

8.9 |

|

New Zealand total land area |

27.1 |

100.0 |

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (2001)

* Mostly land with no potential for sustainable production, towns, lakes, rivers and unclassified areas.

Role of the forest industry in the economy

New Zealand is geographically isolated from major world markets, so innovations to increase productivity and competitiveness are cornerstones to survival and growth, including plantation forest development. Fertile soils, abundant rainfall in most areas and few temperature extremes, provide ideal conditions for growing trees. In addition, no part of the country is very far from a seaport.

Timber has always played a significant role in the New Zealand economy, and in the early development of the country it was the principal export. Many of New Zealand’s small towns started as lumber camps. As European settlement increased, a strong local timber market developed with wood required for housing, fuelwood, fencing, gold mining, construction and, in due course, railway sleepers. The indigenous timber industry reached a production peak in 1907 and then declined as the prized kauri (Agathis australis) forests were logged to near extinction. The development of a plantation-based forest industry began with the establishment of a State Forest Service in 1919. There are now 1.8 million ha of plantation forests. Plantations cover seven percent of New Zealand’s land area and comprise 29 percent of the total forest area.

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry

Figure 1: New Zealand’s indigenous and plantation forests by region

In the year ended March 2002 (provisional figures):

An estimated 20.9 million m3 of wood were harvested from New Zealand’s forests (99.7 percent of which came from the plantation forests);

The average recovered volume from plantations was 482 m3 per ha harvested, and the average age of the harvested radiata pine was 27 years;

13.5 million m3 were processed domestically by New Zealand’s industry mix of four pulp and paper companies, eight panelboard companies, more than 350 sawmillers and approximately 80 manufacturers;

The estimated roundwood equivalent of 14.3 million m3 were exported, in raw and processed forms, earning NZ$3.6 billion and ranking forestry third in terms of commodity exports;

The estimated roundwood equivalent of 1.7 million m3 of forest products (December 2001) were imported (largely paper and paperboard); and

Forestry directly provided jobs for 24 300 people or 1.3 percent of the total number of people employed (as at February 2001).

New Zealand accounts for 1.1 percent of the world’s total supply of industrial wood. This generates 1.3 and 8.8 percent of the world and Asia-Pacific trade in forest products, respectively. However, the New Zealand forest industry has huge potential. Looking forward to 2010, the industry based on plantation forests could:

Cover 2.2 million ha or eight percent of New Zealand’s total land area (at a planting rate of 40 000 ha per year);

Supply 31 million m3 of wood per year;

Account for 1.9 percent of the world’s industrial roundwood (based on current total world production);

Invest up to NZ$3 billion in new wood processing facilities if most of the predicted annual production of 31 million m3 was processed domestically;

Add NZ$5 billion to current export earnings; and

Provide employment for an additional 20 000 people.

Role of public and private sectors in forestry

From 1919 to March 1987, the government’s commercial forestry operations were administered by one agency, the New Zealand Forest Service. In the mid-1980s, New Zealand underwent radical reforms moving from a regulated to a market-based economy, and there was significant re-organization of government agencies. In 1987, the government announced its intention to sell its entire plantation forest estate. This involved 550 000 ha, or about half of New Zealand’s plantation forest resource at the time. The Department of Conservation manages the government’s indigenous forest estate. The Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry has policy, sustainable development, forest health and protection (quarantine) functions. Forest research is carried out under contract to government and private enterprise.

Generally, New Zealand has enjoyed stable and transparent governments with sound legal, policy, planning and institutional frameworks in all sectors. This played a significant role in encouraging overseas investment in forest assets. Central government now controls a mere three percent of the country’s plantation forests. State-owned enterprises and local government control another three percent each. Through the sales process, the face of New Zealand forestry has become more diverse and international. There are 20 companies that each manage more than 10 000 ha of forest. Small-scale growers are increasing their presence. Increased competition and greater exposure to international market fundamentals have enhanced the industry’s competitiveness and its contribution to the New Zealand economy.

Current forest production and conservation policies

The government’s focus has shifted from direct involvement in the industry to promoting economic and regulatory environments in which the forest industry acts for itself wherever possible - to seize economic opportunities, protect and enhance the environment and, in the process, to advance New Zealand’s social goals. New Zealand has no national forest policy at the moment. The Resource Management Act 1991 sets the legislative framework for the sustainable use, development and protection of land, air and water resources. It is implemented primarily at the regional and district government levels. A 1993 amendment to the Forests Act 1949 requires indigenous forests on private land to be managed under approved sustainable forest management plans or permits where timber is to be harvested, and sawmills processing indigenous timber to be registered. The amendment also introduced further controls on the export of indigenous timber products.

General overview of plantation forest development

As early as the 1870s, concern was developing over the rapid rate of indigenous forest depletion. Some leading politicians recognized that the indigenous forests were not inexhaustible and future demands would have to be satisfied by imports or plantation forests. The first forestry legislation was passed in 1874 in an attempt to limit deforestation. It did not endure against the dominating view that forests impede the development of agriculture. Further legislation in 1885 set aside state forests, established a school of forestry, and appointed forestry staff. The interest shown in forestry at that time was again short-lived.

Apart from early European settlers’ efforts to provide shelter or beautify some treeless areas, tree planting took place only from 1871, encouraged mainly by local governments. Central government afforestation took place from the late 1890s under the Lands Department, and about 16 000 ha were planted by 1919.

In 1913, a Royal Commission on Forestry identified some of the main forestry and timber problems, and predicted that the growing demand for timber would exhaust the supply from the indigenous forests in approximately 50 years. The First World War delayed implementation of the Commission’s recommendations, but also highlighted the importance of adequate timber supply. In 1919, the newly established State Forest Service incorporated exotic forestry, indigenous forestry and indigenous forest regeneration under its responsibilities. Further and enduring legislation was passed in 1921 and 1922. These initiatives provided a boost to forest management and afforestation.

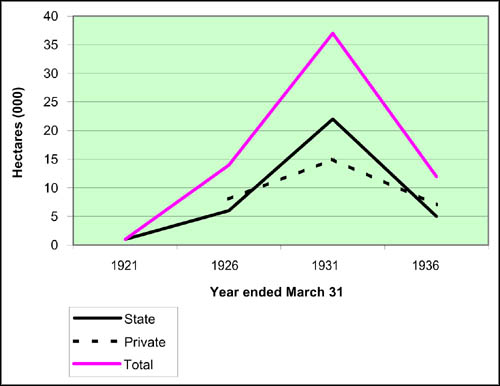

The assessments of indigenous timber resources and future domestic timber demand, and the concern that the indigenous forests would be depleted, led to the adoption of large-scale afforestation by the government. This was accompanied and supported by technological developments that significantly improved the economics of forestry and lowered the risks. Growth and yield performance led to radiata pine becoming the species of choice. Between 1925 and 1936, about 288 000 ha were planted. Initially this was a government undertaking, but once the financial rewards and technologies were firmly established, the private sector quickly responded and contributed significantly to the planting boom. The largest afforestation company (New Zealand Perpetual Forests Ltd.) planted 68 000 ha during this 12-year period.

From 1936 to about 1960, little planting was undertaken. Initially this reflected a review of Forest Service Policy that noted the prominence given to exotic plantations in the preceding years. A more balanced approach was subsequently pursued to complete the establishment of existing forests, rather than focus on the silvicultural treatment of indigenous forests.

Another important factor was the 1937 discovery of a remedy (cobalt) for so-called “bush sickness” on the pumice lands of the central North Island that had severely restricted the development of agriculture. This land was ideal for forestry and was where most of the large-scale afforestation had taken place. With the discovery of a cure, the prospects for further large-scale afforestation diminished. Mistakes were also made in these early plantings with poor siting in particular leading to extensive failures of radiata pine and other species. A major fire and an insect epidemic over a large area were other factors that caused foresters to reflect upon appropriate management practices.

The 1940s and 1950s were also times of great change for processors and end-users who had been accustomed to high quality, indigenous timbers, but were now increasingly faced with non-durable pine from untended early plantings, which contained many defects. The State Forest Service devoted considerable attention to utilization issues.

With the significant production and demonstrated returns from plantations, the building of a processing sector utilizing plantation-grown timber, plus a re-assessment of future demand and the desire to create an export industry, the government initiated a second wave of planting in the early 1960s. This time the circumstances were somewhat different - the government also needed to provide political support and financial incentives apart from demonstrated returns and adequate information.

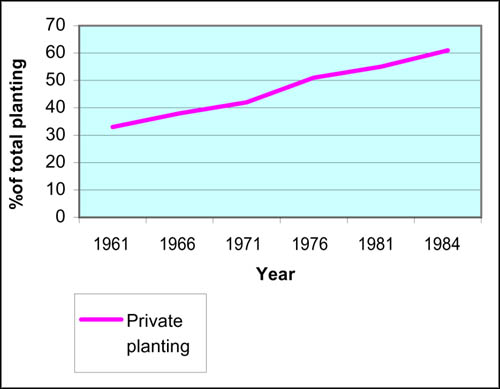

Since 1960, the government progressively introduced a range of support measures to accelerate tree planting on private land. As with the first planting boom, this expansion was driven by the Forest Service. Again, the planting was largely with radiata pine. The ever-increasing amount and complexity of the government incentives to forestry characterized this period from the early 1960s to the mid-1980s. The plantation estate grew from 352 000 ha in 1960 to over one million ha by 1984, of which nearly half was on private land.

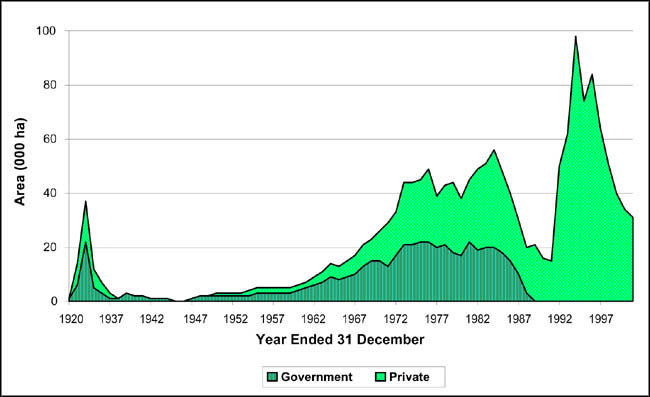

Deregulation in 1984 changed the New Zealand economy from one of the most controlled to perhaps the most open economy in the world. Direct incentive schemes were terminated, extension services became cost-recoverable and significant changes were made to the taxation regime that applied to forestry. The government’s commercial forestry activities were initially corporatized, then privatized in the early 1990s. This combination of events resulted in a dramatic drop in new planting. By 1992, the bulk of the government’s plantation forest assets had been sold. Further changes to the taxation regime were introduced and the government actively promoted forestry investment, mainly through the provision of information. Development of the supporting infrastructure, such as ports, railways and bridges, in most regions was another key facilitating factor. Declining agricultural product prices and land values also had an important influence on the competitiveness and profitability of forestry. Agricultural landowners recognized the value of forestry in diversification and sustainable management. Most importantly, a global price spike for logs in 1993 and 1994 drew unprecedented interest in forestry. These factors buoyed private investment and were important in attracting foreign investors and forest managers, who brought capital, plantation development expertise, technology and crucial access to foreign markets. As a result of these influences, new plantings surged to record levels during the mid-1990s. The last few years have seen planting decline to a perhaps more sustainable long-term rate as log prices returned to more traditional levels.

Having progressed successfully from public plantation development and ownership to private corporate ownership and expansion, the industry has now moved into another phase where the majority of the new planting is on small woodlots and plantations by private landowners and partnerships. A further sign of the maturation of the industry is the presence of professional organizations and sector associations in the processing and marketing arenas, as well as the constructive working relationships that have been built up over time with key stakeholders - the government, research organizations, civil society and environmental groups.

The enduring nature of the newly created forest plantation prompted the following observation 30 years ago that still holds true today:

In numerous localities where the indigenous timbers, first the kauri, and later those outside the kauri country became exhausted all that remained as a reminder of once flourishing sawmilling centers were ghost settlements and often not even that. With our predominantly radiata exotic plantations, however, we now seem to have somewhat of a paradox - new and apparently permanent prosperous towns the economy of which is based entirely on these plantations (Simpson 1973).

The history of plantation forestry development in New Zealand has run in parallel with a gradual change in the mindset regarding tree planting. From being appropriate just for “waste” land (i.e. land unsuitable for agriculture) and marginal land, plantation forestry is now being actively pursued as a profitable enterprise able to compete for land with any other activity and contribute to sustainable land management. New Zealand’s plantation forests of 1.8 million ha continue to grow at around 30 000 to 40 000 ha per annum, and are 91 percent privately owned. Radiata pine (Pinus radiata) accounts for 89 percent of the plantation area, Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) another six percent, other softwoods (mainly Pinus spp.) two percent and hardwoods (mainly Eucalyptus spp.) three percent. The plantations are managed primarily for industrial roundwood production, although some smaller areas are maintained for soil conservation purposes. An accord signed between the industry and environmental groups in 1991 recognized commercial plantation forests as an essential source of perpetually renewable fibre and energy, offering an alternative to stop the depletion of the natural forests. At the same time, it also acknowledged the importance of protecting the existing native biodiversity.

Figure 2. Annual government and private new planting

PLANTATION FOREST DEVELOPMENT PRIOR TO 1870

Until 1840, the New Zealand timber industry depended on the harvesting of Mâori-owned indigenous forests. The provincial government in the Canterbury region of the central South Island was the first to encourage tree planting by passing the Planting of Trees Ordinance in 1858. This was mainly to develop on-farm wood resources on leased land in significant treeless areas. The ordinance permitted tenants to plant trees on their land and reimbursed them for the trees if the leases were terminated (see Annex 1 for summary of developments during this period).

INITIAL RECOGNITION OF PLANTATION FORESTRY AND THE BEGINNING OF THE LEARNING CURVE (1870-1918)

By 1870, increasing concerns about the depletion of the indigenous forests led some politicians to acknowledge that future demands for industrial wood from these sources would have to be supplemented by imports or plantation forests. However, the government’s primary objective of promoting European settlement and rapid economic development took precedence over any concerns about the rate of deforestation. Most of the land clearance by Europeans took place between 1870 and 1920.

Legislation

Two reports submitted to the government in 1870 recommended incentives for the planting of trees and provided the initiative for the Forest Trees Planting Encouragement Act 1871. This was particularly targeted at the treeless Canterbury Plains and Central Otago in South Island, where trees were needed for building materials, railway sleepers, fuel and shelter for stock and crops. Under the provisions of the Act, farmers were entitled to a free land grant of two acres[103] of wasteland for every acre of freehold land planted with suitable trees. The government also encouraged tree planting on state land by reducing the rents of tenants who planted trees on their leaseholds. The Act was never fully implemented, nor was it particularly popular with the farmers. By 1877, only 622 acres were planted in Canterbury compared to 1 300 acres that had been planted independent of the Act on private land by 1871.

The first Forests Act (1874) was an attempt to halt the indiscriminate destruction of indigenous forests and establish a forest department specifically focused on ensuring a long-term supply of (indigenous) timber. It provided £10 000[104] for ten years to be spent on forest management, which included planting. However, the first forest conservator, appointed in 1893, saw only a small role for the government in plantation forestry. Government forestry was also seen to be in conflict with settlement aspirations, and the legislation failed after three years.

Under the State Forests Act of 1885, the revenue from harvesting indigenous forests was placed in a dedicated “State Forests Account” from which the costs of plantation forestry could be drawn. The legislation also offered subsidies to local government for establishing plantations. Once again, however, the brief interest in forestry did not endure and the State Forest Department was dismantled in 1887.

Local-level afforestation assistance

Since 1871, large grants of government land were made available to district councils for afforestation purposes. In return, the councils were expected to provide seedlings and funds, and undertake forest establishment, which was difficult to achieve. It was eventually agreed that planting should be gradual and that the areas where planting was deferred could be leased to provide revenue to defray some of the costs. Provincial governments also sought to increase private planting by issuing a land order of £4 to anyone who successfully planted one acre with any type of tree. This scheme lasted for 20 years. It was particularly popular in Canterbury and Otago where the establishment of shelterbelts to provide protection from the prevailing northwest winds was valuable to farmers. Some of these plantations were up to 200 or 300 acres of largely radiata pine or Cupressus macrocarpa. Continuous, small-scale planting, partly funded in this way, provided the foundation for the Canterbury Plantation Board to become New Zealand’s first plantation forest management agency.

Tree planting subsidy schemes had stopped in the early 1890s. By this time, planters had identified species with superior yield potential including several pine species, Douglas fir, eucalypts, cypresses and, in particular, larch (Larix spp.).

Government leadership and national coordination

A turning point for plantation development came in 1896 when the government convened a national timber conference, bringing together timber industry representatives, conservationists and farmers. The conference concluded that, because of the demand for timber, attempts to conserve indigenous forest would be futile without the establishment of plantations. The recommendations, listed hereunder, were well received and adopted:

It is desirable to commence the planting of lands unfit for agricultural or pastoral purposes immediately;

Experimental grounds should be established for the raising of various trees and the supply of trees at nominal cost to those willing to make plantations for timber purposes only; and

Advice and direction should be afforded by the government to assist private planting for forestry purposes.

Government afforestation

The government responded in 1896 by establishing an afforestation branch within the Lands Department, and the first government-organized afforestation commenced. The government implemented an annual planting programme that focused on land in the central North Island volcanic plateau, considered deficient for farming. The first tree nurseries were also established. Fifty-four acres were planted in 1898 and numerous trials were established to compare indigenous with exotic species and determine the most suitable trees for plantations. Initially, labour constraints hindered the expansion of plantation forestry, but tree-planting prisons were established and convict labour was used until 1920. By 1904, afforestation was up to approximately 1 000 acres of new planting per year. Planting was targeted at government land near railway lines where there was little existing adjacent forest.

By 1908, 9 465 acres of plantations were established. These plantings illustrated that exotic plantations were technically feasible, although the cost of establishment was high. The average figure was £20/acre (approximately NZ$5 970/ha in December 2001 values[105]).

Government supply and demand analysis

In the early 1900s, the quality and quantity of indigenous timber were diminishing rapidly. It was estimated that the supply was likely to be exhausted in less than 70 years (Kensington 1907). Demand for wood was also growing quickly. Between the turn of the century and 1908, imports had increased fivefold despite indigenous timber production doubling over the previous ten years. A Royal Commission on Forestry set up in 1913 recognized the limitations of the indigenous forest to meet future timber supply, the unsatisfactory fragmentation of forestry administration and a lack of interest in afforestation by the administrators. The Commission suggested that indigenous species, and even the most commonly planted exotic at that time - larch, were unsuitable for plantation purposes, but did note that Pinus radiata was being raised in quite insufficient numbers. The strong performance of pine species in New Zealand was becoming evident. Its roles in controlling erosion and stabilizing sand dunes were also recognized.

Government support and indigenous timber controls

In 1908, the government responded to industry lobbying by introducing reduced rail freight rates for timber, which cost the government between £25 000 and £35 000 (approximately NZ$3.0 to 4.2 million in December 2001 values). Forestry was given a considerable stimulus when the government began supplying seedlings to settlers at cost price for farm planting as early as 1916, and assisted further through the provision of extension.

The repatriation of 1914-1918 soldiers, an increase in the number of marriages, higher wage rates and a general feeling of prosperity, all led to a high demand for construction timber. This situation was fuelled by substantial government housing subsidies for returned soldiers. During, and for some years after the war, discharged soldiers were also eligible for grants of forest trees for farm purposes.

The growing concern over the fate of New Zealand’s indigenous forests resulted in the introduction of wide-ranging regulations in 1918 to control timber milling and exports. The Minister of Forestry was empowered to set the maximum production at each sawmill, require millers to report their activities and impose a system of export and domestic price controls. Later, export quotas were introduced and permits required for timber exports to control domestic prices with the aim of “conserving New Zealand timbers for New Zealand use”.

Period summary and conclusions

The period was notable for the gradual change from viewing

indigenous timber supply as inexhaustible to a realization that existing forest

resources were inadequate to meet the country’s future needs. Accordingly,

increasing government involvement in the forestry sector took

place.

Development and implementation of forest policy and legislation were

severely constrained by the European pioneering attitude that saw forests as

obstacles to settlement and agricultural development. While land settlement

reached its peak around the turn of the century, forestry continued to be

perceived only as an alternative where agriculture was uneconomical. The

government attempted to address these issues many times, but overall political

support was weak until the end of the period. Land grants were the principal

direct means of encouragement for plantation forestry. Initial steps by the

government to develop a viable industry and knowledge on afforestation, and the

gradual refinement of cost-effective planting techniques, provided some indirect

incentives. By 1918, a toehold of some 13 000 ha of plantations had been

established, most of it encouraged, but not owned, by the government.

The government also impacted on the timber industry through duties and tariffs, adjusting rail freight rates and establishing new wage bargaining procedures. These were generally ad hoc responses either to crises in the timber industry, rising production costs, or increasing competition from imported timbers. The First World War led to the introduction of export price controls and quotas in an attempt to provide low-cost raw materials for postwar construction. Whilst this policy achieved its objectives, it also meant that even greater incentives were required to persuade private individuals to grow trees. Annex 1 summarizes incentives for plantation forestry development provided during this period. Conclusions about these incentives are:

A fundamental and long-term need for wood was accepted;

Plantations could readily substitute natural forests to nearly satisfy this need;

To implement plantation strategies, incentives are required because of the time lag between establishment and maturity;

In an environment dominated by short-term objectives, the New Zealand Government had an important role in demonstrating and developing the management for a new land use - plantation forestry (based on exotic species);

Incentives are ineffective where they are at odds with the prevailing attitudes, and their success is significantly impeded if other policies are inconsistent with the objectives of the incentives; and

Fragmentation in government administration hinders the development and implementation of effective policy for land use and industry.

LARGE-SCALE GOVERNMENT PLANTING (1919-1938)

In 1919, the State Forest Service was formed, and experienced, trained, professional foresters were appointed to senior positions. The Forest Service initially adopted a new policy direction away from afforestation, export restrictions and price controls, and towards a more comprehensive government forestry programme focused on sustainable management of indigenous forests. It was believed that this would be enough to assure future supplies of timber for the country.

The first national forest inventory, carried out between 1921 and 1923, revealed that five million ha, or around 20 percent of the country, could be classified as forest land, of which only 45 percent (2.24 million ha) was merchantable. Furthermore, the 1925 annual report of the Forest Service estimated the total economically available indigenous softwoods at around 60 million m3, and the per capita consumption of the 1.35 million inhabitants of New Zealand at a little over 0.5 m3 per annum. Based on population trends and the expansion of industry, particularly agriculture, it was further calculated that by 1965, the national demand for sawntimber would be 1.6 million m3, and that New Zealand’s virgin softwood supplies would be exhausted by 1970.

These results forced a policy rethink. Timber product substitution was not considered feasible, and increasing reliance on imports was perceived as costly and creating an unwelcome dependence on overseas supplies. Despite the uncertainties of large-scale afforestation, it was viewed as the only solution, and from 1925 onwards afforestation became a central plank of forest policy. Thus, the conclusions of 20 years earlier were reconfirmed and the afforestation solution was pursued with renewed vigour. This became the rationale for the extensive government forest planting and the incentives to encourage private companies, local authorities and private individuals that followed.

An official report calculated that about 238 000 ha of radiata pine planted over a 34-year period would be needed to supply expected demand, assuming no remaining indigenous forest resources. A new afforestation strategy was announced, which recommended that the 5 200 ha of government plantations that existed in 1925 be increased to 120 000 ha by 1935 to meet New Zealand’s timber needs from 1965 onwards. The early learning phase had provided much of the groundwork that allowed planting on this scale to be contemplated.

Research

An improved seed collection service was introduced in 1923 to counter the impacts of poor, and inconsistent, tree-form characteristics. Silvicultural research efforts had focused on ascertaining the most appropriate time to plant, spacing, maintenance of soil fertility, shade requirements and fertilizer response. A separate stream of research was concerned with insect pests and fungal diseases of trees. Forest product research, including kiln-drying, physical and mechanical properties of various timbers, timber treatment and preservation, and pulp and paper potential, began in 1921. By 1925, when the first planting boom occurred, there were already some five or six years of useful results from government-conducted research to draw from. Dedicated forestry schools were also established in Canterbury in 1925 and Auckland in 1926, although both closed in the early 1930s.

Government support

From 1921 to the end of 1930, the sale of seedlings at cost price from government nurseries for private planting was also given considerable emphasis, and resulted in a significant number of trees being planted. In 1927 alone, some 4.8 million trees were supplied from government nurseries to individual landowners. Much of this planting was for shelter and on-farm uses, rather than for commercial returns. The government ceased to supply seedlings in 1930 after submissions from the Nurserymen’s Association that considered it to be unfair competition.

From 1921 to 1930, the State Forest Service employed a North Island and a South Island officer whose role was to travel the country giving addresses and dispensing advice on tree planting. This was supported by extensive Forest Service research into the growth, yield and potential of various exotic species, although a forest research institute was not established until 1947.

Improving the economics

Improvements in afforestation and planting techniques, particularly between 1921 and 1924, reduced the cost of establishing plantations from £26.18/acre in 1918 to less than £2/acre in 1925. This eliminated one of the principal objections to afforestation - that it was uneconomical. The goal of 120 000 ha by 1935 became a national policy. Direct sowing of tree seeds and wider spacing between planted seedlings were also introduced. By the mid-1930s, the cost of planting in the central plateau, where half of the planting was taking place, remained at around £2/acre (approximately NZ$408/ha at December 2001 prices).

Provision of labour

Convict labour comprised the bulk of the labour force used in government afforestation up until 1921. This was supplied free-of-charge to the Forest Service at first, but for about six years until 1921 the Forest Service (and its predecessor) was charged the actual cost of maintaining the convicts, which illustrates the true cost to government. From 1921 onwards, the Forest Service no longer used convict labour, and workers were drawn instead from the ranks of the unemployed.

During the Great Depression, subsidized work relief programmes gave considerable stimulus to the government’s afforestation programme. Tree planting under public works’ relief schemes was widespread during the 1930s and the target of 120 000 ha by 1935 was exceeded by 25 percent in 1934. Another government response during the Depression was to provide a subsidy for construction of houses equivalent to 33.3 percent of wages up to a maximum of total construction cost. This had obvious linkages to the timber industry. Freight rate concessions were also available.

Government plantation forestry

Government plantation establishment was financed by loans with compounding interest, rather than annual appropriations. Combined with forest revenues that could be applied to non-planting purposes, annual receipts were consequently insufficient to meet accumulated debts. In one of the worst cases, the expected yield from Dumgree Forest established in 1903 was less than five percent of the accumulated debt, largely due to compounding interest.

Between 1927 and 1932, exotic pine production increased from 17 500 to 32 000 m3, although still only representing six percent of total production. Twenty percent of this exotic production came from government forests and was typically used domestically for poles, sleepers, mine props, posts, battens and fuel.

A new forest policy in 1934 de-emphasized the importance of expanding the plantation estate, and large-scale forest planting ceased. Exotic plantations were seen as “supplementary forest resource capital”. In view of subsequent events, the reasons are worth noting. Firstly, halting large-scale plantings was perceived to be appropriate because it was considered that plantation resources were sufficient to supplement indigenous forests for the next century. In addition, surplus exotics were envisaged to be export oriented and therefore would not be competitive in the international market.

Diversification was also emphasized so that no species would form more than 30 percent of the total resource. This strategy had been given impetus by outbreaks of the wood wasp (Sirex noctilio) and fungal infections. A more limited afforestation programme continued, partly to reduce the proportion of radiata pine from its 40 percent level in 1934 to the 30 percent target, and partly to improve the age class distribution.

Private afforestation

Concurrent with the government forestry expansion was a private forest-planting boom, although for very different reasons. Initial work by the Forestry Branch of the Lands Department and subsequent research undertaken by the Forest Service provided knowledge on species suitability, growth rates and planting techniques. Consistent with research results on the performance of the government’s exotic species plantations, the harvest of some older private exotic forests and shelterbelts resulted in attractive returns. The investment potential of plantation forestry had been demonstrated. In response, several private companies were formed after 1923. These new afforestation companies benefited from the government’s experiences, and were speculating on reaping the financial rewards of the new industry.

Besides special-purpose afforestation companies, other enterprises with an interest in securing a long-term supply of timber were attracted to the government’s tree-planting efforts. These included some sawmilling companies and other wood users. Capital was raised by means of bond sales[106] through public offerings. Combined with the government’s efforts to encourage plantation forestry, significant new private plantings took place.

When the Great Depression commenced in 1929, the New Zealand timber industry was already in recession. From 1928 to 1934, timber prices fell due to oversupply from the indigenous forests and competition from imports, even though the government withheld timber from sale to support the private industry. New Zealand timber was increasingly displaced by imported timber such as Douglas fir, cedar and redwood, despite increasing import duties on timber. This trend eventually spelt the end for many companies, and new plantings by surviving companies fell steadily during the early 1930s (Figure 3), mirroring the fall in the government plantings, but for different reasons.

Abuse of the bond-selling system[107] by private companies eventually led to its abolishment and to changes in the legislation governing companies in 1934. This accentuated the decline in private planting.

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (2001)

Figure 3: Trend in annual new area planted between 1921 and 1936

Period summary and conclusions

The formation of the State Forest Service, an inventory of the natural forest resource and assessment of the country’s future timber demand laid the foundations for plantation forestry in New Zealand. The Forest Service’s main objective was to ensure an adequate, long-term timber supply. Substantial areas of government and private plantations were established.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the government implemented forest policies that provided both direct and indirect incentives for the development of the forest industry. In addition to a government afforestation programme, these measures included a government extension service, the development of forest management techniques, research, unemployment relief, housing subsidies and price controls.

This was very much an experimental phase. A number of extensive planting failures occurred where radiata pine was planted on inappropriate sites. Afforestation was concentrated on land not suitable for agriculture and, in a number of cases it was also poor for commercial forestry. Some plantations were destroyed by fire.

The inadequate age class distribution was another concern. Eighty percent of the Forest Service’s radiata pine forests and 50 percent of the private forests were established between 1927 and 1931. This posed significant management problems. Importantly, though, for the development of the plantation forest industry, the government bore the bulk of the costs associated with this experience. By 1938, both government and private planting had effectively ceased, and most of the plantation estates were between nine and 13 years old.

A summary of incentives and disincentives during this phase is available in Annex 1. The conclusions from this period with respect to incentives for plantation forestry are:

Integrated forestry administration was important for the development and implementation of a cohesive forestry policy;

A well-funded research programme on all aspects of plantation forest management was essential;

A good understanding of forest resources and likely future demand for wood were fundamental components of an enduring afforestation policy;

A good understanding of the product, its management and end uses were essential for commercial viability;

A wide range of direct and indirect incentives for plantation forestry existed, and different interest groups responded according to their various motivations for planting;

Government demonstration of the commercial viability of plantation forestry attracted private investment, particularly from companies; and

With experience and research, new opportunities became available, such as the emergence of viable export products.

CONSOLIDATION AND FOCUS ON UTILIZATION (1939-1958)

Afforestation, particularly private planting, was limited during the 1940s and 1950s. Meat and wool farming were especially buoyant during this period and tree plantings on farms were unable to compete when, at the same time, the government was maintaining timber price controls. In addition, the government’s focus moved away from plantation development to processing. From 1939 to 1958, the total area planted reached only 55 000 ha. Private planting picked up only during the latter part of this period and accounted for 16 000 ha (29 percent) of the total.

The planting of radiata pine during the 1920s and 1930s in concentrated areas provided large quantities of relatively uniform raw materials in the late 1940s. The advantages gained - low logging and transport costs, and bulk marketing - were important to the development of the processing industry, and outweighed the disadvantages of poorer wood quality from untended radiata pine stands.

Table 3: Estimated roundwood removals from New Zealand’s forests between 1939 and 1958 (000 m3)

|

Year ended 31 March |

Indigenous forest |

Plantation forest |

|

Average of 1936 to 19398 |

1 387 |

226 |

|

1948 |

1 455 |

829 |

|

1950 |

1 624 |

934 |

|

1955 |

1 610 |

1 845 |

|

1959 |

1 573 |

2 394 |

Sources: New Zealand Forest Service (1986); Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (2001)

Subsidized processing and associated infrastructure

The Forest Service’s involvement in commercial logging and processing was very important in consolidating the economics of plantation forestry and expanding the demand for products from the developing plantation resource. In 1939, the government commissioned a large sawmill near Rotorua, adjacent to the major central North Island plantings. Another major government sawmill, Conical Hill, began operating in South Island in 1948. These sawmills served as demonstration and development units for production and marketing techniques for the sale of exotic plantation-grown timber, and in having radiata accepted as construction timber. The industry was quick to follow with a major private company (NZ Forest Products Ltd.) commissioning an integrated sawmill-structural board plant in 1941 that utilized radiata pine.

Research was required to develop grades and to determine seasoning, preservation practices, strengths and physical properties of plantation-grown timber. In 1948, the Forest Experiment Station (now Forest Research) at Rotorua was established by the government as the base station for a national indigenous forest inventory, but its work soon extended into exotic species. The value of a centralized research institution was quickly illustrated during a sudden epidemic of the Sirex wood wasp in the late 1940s.

The first commercial pulping of radiata pine commenced in 1939 by Whakatane Board Mills. In 1943, as part of a “National Pulp and Paper Scheme”, the government approved the establishment of a newsprint and pulp and paper mill. A change of government in 1949 resulted in a policy shift favouring private over public ownership. In 1952, the government signed an agreement with the Tasman Pulp and Paper Company, and a pulp and paper mill was established at Kawerau in central North Island. An important aspect of this arrangement was the degree to which the government, as the owner of the wood resource, made the venture as attractive as possible by selling a very large volume of wood at low stumpage prices, effectively subsidizing the mill’s profits. Weighing the benefits of establishing a plantation industry - with associated downstream processing facilities - against the cost of selling the logs at below-market value would have been a difficult exercise and was very much a political decision. In essence, “The direct and secondary benefits to the community are, politically, close to being irresistible, while below-market pricing of logs is practically invisible under most systems of Government accounting” (Kirkland and Berg 1997).

The government also agreed to: (i) construct many miles of new roads and a modern port facility at nearby Tauranga; (ii) supply energy from hydroelectric power stations and (iii) establish railway lines to link the plant with the existing rail network and new port. It constructed over 700 rental houses and 550 one-man huts for the workforce, plus all necessary town services. The £14 million cost (approximately NZ$511.8 million at December 2001 prices) to the government for providing this support represented almost 50 years’ gross revenue under the terms of the sale agreement. This was before the additional cost of the low stumpage price was factored in. Furthermore, the contract was effective for 75 years and thus locked the government into providing wood from yet unplanted forests.

By comparison, NZ Forest Products Ltd. initiated parallel development of an integrated sawmill and pulp and paper mill in 1949 without direct government participation. This was based on its almost equally extensive exotic forests in central North Island and commenced operation in 1953.

In 1957, the first log shipment in 50 years went offshore, this time of radiata pine. Exotic sawntimber production exceeded indigenous production for the first time in March 1960.

Tax relief

Tax relief was provided from 1949 to farmers who had forest plantations. This allowed expenditure incurred in planting, protecting and maintaining shelterbelts and woodlots, to be charged against income for tax purposes. In addition, farmers were able to spread income from the sale of farm trees over five years to mitigate the impact of higher marginal tax rates. The standing value of trees did not increase the assessment for land valuation and local tax rates. Little planting by farmers was undertaken, however.

Price controls

In 1936, the government had established a Timber Price Committee due to demand exceeding supply following the end of the Depression. The Committee set standard timber prices through negotiations with sawmill representatives.

Demand was further increased by the start of the Second World War and the government assumed even greater powers by appointing a Timber Controller with authority to undertake the sale, purchase and cutting of any trees. After the war, demand for new housing outstripped supply until the mid-1950s. Building permits for dwellings rose from 1 634 in 1943 to 10 356 in 1945 and 1946. Government price controls were continued to address a significant backlog of construction needs, and to ensure affordable housing. They applied to both indigenous and exotic timbers, and kept stumpage payments low. These controls slowed down the anticipated shift from indigenous to exotic timber, as did the continued access by sawmillers to private indigenous forests. A government scheme introduced in 1946 that allowed sawmillers to provide subsidized housing to attract workers into the countryside was also likely to have benefited the indigenous forest industry more than plantation forestry.

Under the price controls, valuable indigenous timbers were available at the same prices as radiata pine, with minimal price differences across timber grades. Throughout the 1950s, the Forest Service and private forest companies argued that such price controls needed to be removed if exotic plantation timber was to have any chance of substituting indigenous timber. Price controls were considered a significant disincentive to tree planting. The government, however, was more concerned with ensuring low-cost timber for housing and employment opportunities, and timber price controls were not removed until 1965. The government also regulated the supply of timber.

National forest survey

A major new national forest survey of the indigenous resource (1946 to 1955) provided high quality information on the resources and composition, condition and ecology of the forests. Only 0.8 million ha of the estimated 5.8 million ha of indigenous forest were considered suitable for timber utilization. The results confirmed that timber supplies from indigenous forests could be sustained at the current rate of harvest for only a few more decades. The government consequently accepted that sales of timber from indigenous forests should be reduced.

Period summary and conclusions

The focus of this period was on the utilization of the maturing plantation trees, with only limited further plantation development. Notably, a new Director of the Forest Service appointed in 1939 was a forest product engineer. The impacts of the earlier planting were significant as a very large volume of poorly and rapidly grown wood, mostly radiata pine, began to replace the high-quality native timbers that had been used so successfully for the previous hundred years. Access to large, concentrated volumes of uniform plantation wood that could be harvested easily overcame the disadvantage of poorer quality relative to wood from indigenous forests.

In some respects, New Zealand’s extensive plantation forests had been grown speculatively, and this was the period of developing a better understanding of their management, the wood properties and their utilization potential. The government responded by providing significant subsidized development of the infrastructure necessary for processing the wood.

Annex 1 highlights the incentives and disincentives available during this period. The conclusions drawn with respect to incentives for plantation forestry are:

Development of infrastructure by government paved the way for large-scale processing initiatives based on plantation-grown timber;

Government ownership of extensive plantation forests enabled the provision of low-cost wood to facilitate the development and success of new, large-scale processing;

Logging, sawing and marketing techniques developed by the Forest Service played a significant role in ensuring the development of exotic plantation forestry;

The real cost to the government for the incentives was not documented, but it was considerable and unlikely to have been justified purely on its financial merits. Some developments might have taken place anyway (and indeed did);

The contributions to broader economic development and social goals could be sufficient to make the financial costs politically acceptable;

Price controls inevitably depressed further expansion of plantation forestry, and revealed how the implementation of other policies could significantly reduce the impact of incentives; and

Taxation incentives on their own were insufficient to persuade farmers to adopt plantation forestry.

PLANTING IN PARTNERSHIP AND DEVELOPING AN EXPORT INDUSTRY (1959-1984)

The large increase in plantation wood in the mid-1950s from the first planting boom gave rise to strong growth in the industries and trade. The anticipated demand from these new industries triggered perceptions of further future wood shortages. Another assessment of New Zealand’s future wood supply needs was undertaken for the government. Its report in 1959 predicted a deficit of 5.4 million m3 in 2000.[108] This assessment stimulated a second major afforestation effort. Much of the planning was also based on developing an export capacity. From 1959 onwards, the Japanese log trade increased significantly. It was delivering prices well in excess of what was available in the domestic market, and made forestry a more competitive and profitable form of land use.

A threefold increase in planting was proposed and in 1960 the government approved a new planting programme of 400 000 ha by 2000, principally aimed at creating a major export industry. Annual planting targets were steadily increased from 9 000 ha/year in 1959 to 28 000 ha/year in 1972.

Unoccupied land available for either agriculture or forestry was limited and it was recognized that the government (through the Forest Service) could only contribute to part of the target. It was envisaged that the government and the farming community would need to contribute equally to achieve the required level of new planting. This meant winning the support of a farming community that was, in general, wary of any further plantation expansion. Initially, the targets of the planting programme could not be met because the government had difficulties in purchasing sufficient land for planting, and because of the farmers’ limited interest. Price controls, still in effect until 1965, were another obstacle to afforestation.

A small farm forestry movement had been initiated in the late 1950s and achieved some success in promoting small-scale forestry and the use of a more diverse range of exotic species. Despite the government’s promotional efforts, however, these efforts were not enough to encourage sufficient numbers of farmers to plant trees. Similarly, the exemption of the timber value of trees from estate duty in 1960 had little effect. Moreover, financial institutions were reluctant to provide loans to forestry enterprises because of their inexperience with such investments. More direct incentives were considered necessary, and were quickly and increasingly brought into play. In 1972, planting by the private sector exceeded that of the government for the first time since 1939.

Government promotion

For the first time, forestry was actively promoted by the Forest Service as a legitimate land use in its own right, and began to compete with agriculture for more productive land. The Forest Service devoted considerable time and resources to promote the benefits of forestry as a land development option that complemented agriculture. It also supported research on the relative profitability of farming compared with forestry, and provided technical advice through a nationwide extension service. However, impediments to expansion remained, the most important being prevailing attitudes and the legislative environment.

The increased rates of tree planting in the 1970s resulted in a vigorous “farming versus forestry versus the environment” debate. Although afforestation was concentrated on cutover indigenous forest and poorer quality farmland, many in the agriculture (livestock) industry still strongly viewed plantation forestry as a waste of good land. This was particularly focused on large-scale plantation forestry undertaken by private corporations and the government.

Other arguments against plantation forestry focused on the disruption of existing rural communities by a new land use that changed the social structure and supporting services. Typically, forest workers were younger, often single, and were concentrated in fewer and larger towns. Large-scale plantation forestry did not involve family ownership and land management. It was blamed for increasing urban migration and thus the consequential loss of education, health, transport and other social services in rural areas. Farmers expressed fears of becoming surrounded and isolated by plantations because they could not compete with the corporate sector in purchasing land. However for those who sold their land, forestry provided an additional and welcome exit opportunity in many cases.

The situation was compounded by a general disinterest in forestry among the agricultural community. There was little interaction between the forestry school (established in 1970) and the agricultural universities. Courses in agroforestry were only introduced into the agricultural universities in the 1980s. Consequently, farm advisers, trained in livestock production techniques, had little experience or interest in promoting trees.

The farming versus forestry debates also continued in the statutory planning arena, particularly under the Town and Country Planning Act (1977), and polarized the parties involved. The Act listed the protection of land having actual or potential value for food production as a matter of national importance. This was supposed to control urban development on high-quality agricultural land, but the provision became a convenient mechanism for local authorities to justify the control of plantation expansion. Throughout the 1980s, this restriction had a significant, although unquantifiable, impact on the development of plantation forestry while agriculture remained largely free of any controls.

Loans and grants schemes

Forestry Encouragement Loans 1962

Prior to 1962, farmers found it difficult to obtain finance for forestry purposes. The government introduced Forestry Encouragement Loans under the Farm Forestry Act (1962). Landowners could borrow money for up to 20 years at an annual interest rate of five percent (inflation at the time was three percent per annum), including a provision for insurance up to the amount borrowed. Loans could be sought for the establishment (£25/acre or approximately NZ$1 871/ha in December 2001 values) and tending (£15/acre or approximately NZ$1 123/ha in December 2001 values) of areas from five to 100 acres (2-40 ha), over a five-year period. The amount was intended to cover the full cost of establishing a small forest or farm woodlot. Half of the loan and half of the interest were refundable after 20 years if the plan was implemented satisfactorily. Priority was given to areas with high timber demand, close to population centres, and where forest industries were present or expected to develop.

Despite these measures, the area planted remained significantly below target. In 1965, the Farm Forestry Act was modified and renamed the Forestry Encouragement Act. With this amendment, local governments could take advantage of the terms and request loans for up to 40 years. The rate of interest payable on new loans was reduced to three percent, with interest only charged on the non-refundable half of the loan. Another option was provided to compound interest up to the point where the forest began earning income. The limit of 100 acres (40 ha) as the maximum area able to be planted over a five-year period was removed to enable greater areas to be planted with the approval of the Ministers of Forests and Finance.

In 1962 and 1963, 57 planting loans and 11 tending loans were provided. This rose to 100 and three respectively by 1966/1967, but still the area planted remained considerably below target (Table 4). Amendments to the Forestry Encouragement Loans were made virtually every three years, when the maximum loan finance and interest rates were varied to account for inflation.

It is unclear why the areas planted were such small proportions of the area for which loans had been granted. The economics showed the planting under the loan scheme to be considerably cheaper than that carried out by the Forest Service.

Table 4: Area planted during the first five years under the loan scheme (ha)

|

Year ended 31 March |

Area granted (ha) |

Area actually planted (ha) |

Value of loans (NZ$) |

Approximate value of loans in December 2001 values (NZ$) |

|

1963 |

1 236 |

- |

- |

|

|

1964 |

680 |

364 |

27 308 |

406 000 |

|

1965 |

1 086 |

518 |

61 198 |

878 000 |

|

1966 |

3 113 |

462 |

62 324 |

865 000 |

|

1967 |

2 716 |

1 097 |

112 228 |

1 516 000 |

Sources: Reports of the Director-General of Forests (1964 to 1968); Poole (1968)

Forestry Encouragement Grants 1969

In 1969, the government concluded that the rate of planting under the loan scheme was unlikely to ever reach the target. Regulations providing for Forestry Encouragement Grants were introduced in 1970 to gradually replace the loan scheme. Under the new plan, individuals, trusts, partnerships and smaller companies whose qualifying expenditures did not exceed NZ$200 000[109] per year (approximately NZ$2 185 000 in December 2001 values) were entitled to receive annual cash grants equal to 50 percent of the qualifying costs of establishing new forests. A maximum of NZ$750/ha (approximately NZ$8 194 in December 2001 values) was payable and the minimum area eligible was two ha. Such incentives seemed to balance the tax exemptions enjoyed by the larger forest companies.

The two encouragement schemes

The Forest Encouragement Loan scheme was retained for local authorities only. A maximum loan of NZ$1 200/ha was available for establishment and tending of plantations of at least two ha. Interest was charged at seven percent per year (the inflation rate in 1970 was 6.6 percent), of which 0.5 percent was to provide fire insurance.

The loan and grant schemes were amended twice. In 1977, a single interest rate of 4.5 percent was introduced for new loans and the 50 percent loan refund provision was revoked. Farmers with existing loans, and whose planted forests were up to an acceptable standard, had the option to retain their loans, or cancel their existing debts fully and claim a proportion of their future qualifying costs under the grant scheme. The maximum grant amount was increased from NZ$300 to 450 (approximately NZ$1 506 to 2 260 in December 2001 values) per hectare. The Forest Service reported that the area of new plantings was falling because the grants covered only one-third of the establishment costs instead of the intended 50 percent.

In 1980, the financial limits on annual expenditure under the grant scheme were removed. Protection/production grants were introduced and targeted at farmers who wished to work on their properties that needed stabilization themselves. The scheme provided grants of up to two-thirds of the establishment costs, together with half of all subsequent costs.[110]

Forestry Encouragement Grants 1982

In 1982, the government introduced the Forestry Encouragement Grants to provide equitable assistance to all landowners (Box 1). From 1 April 1983, all previous forestry incentives were withdrawn. They were replaced by a flat rate grant of 45 percent of qualifying costs. The new grants were extended for the first time to the larger companies. At the same time, the right to deduct current forestry expenditure from taxable income, which had been available to the forestry companies since 1965, was removed. The effect was to increase the government’s tax revenues and create a large new expenditure item concurrently. In view of the large planting areas involved, the grants were to be controlled clerically, by random financial audits of annual claims, rather than by field inspections of forestry operations.

With the introduction of the Forestry Encouragement Grants, the Forestry Encouragement Loans ended in 1983. Loan holders could choose to maintain their loans, or terminate them and receive grants for further expenditures. Many opted for the grant payments, but most local authorities continued with their loans for cash flow reasons.

The Forestry Encouragement Grants scheme was ended in the 1984 budget, and replaced by full deduction of plantation establishment costs against current income for tax purposes. Transitional loans, to complete the development of existing plantations, were available to previous grant holders through the Rural Bank. Protection/production grant holders remained eligible for grants of up to 39.4 percent of qualifying costs until 1990/1991.

|

Box 1: Activities qualifying for Forestry Encouragement Grants · Clearing and preparing of

land |

Repayments on individual farmer loans (last loans approved in 1970) could last until 2010. Local authority repayments (last loans approved in 1970) could last up until 2023. The current total value of outstanding loans is NZ$34 million, including NZ$19.5 million of capitalized interest.

Achievements of the loans and grants schemes

Nearly 200 Forestry Encouragement Loans were approved over the 20 years of the scheme’s operation. The total area planted under the scheme was 20 000 ha. More than 3 000 Forestry Encouragement Grants were made over the scheme’s 13 years of operation. The total area planted under this scheme was 100 000 ha (Table 5).

Table 5: Private sector forest plantings 1963/1964 to 1983/1984 under loan and grant schemes (ha)

|

Year |

Total new |

Loans |

Grants |

Combined |

Total cost |

Approx. |

Combined |

|

1964 |

4 000 |

364 |

0 |

364 |

27 |

406 |

9 |

|

1965 |

5 000 |

518 |

0 |

518 |

61 |

878 |

10 |

|

1966 |

5 000 |

462 |

0 |

462 |

62 |

865 |

9 |

|

1967 |

6 000 |

1 097 |

0 |

1 097 |

112 |

1 516 |

18 |

|

1968 |

7 000 |

1 702 |

0 |

1 702 |

160 |

2 038 |

24 |

|

1969 |

8 000 |

1 080 |

0 |

1 080 |

93 |

1 136 |

14 |

|

1970 |

8 000 |

(e) 1 162 |

0 |

1 745 |

121 |

1 408 |

22 |

|

1971 |

11 000 |

1 003 |

1 012 |

2 015 |

227 |

2 480 |

18 |

|

1972 |

16 000 |

198 |

3 656 |

3 854 |

371 |

3 672 |

24 |

|

1973 |

16 000 |

1 039 |

3 757 |

4 796 |

558 |

5 165 |

30 |

|

1974 |

23 000 |

1 420 |

5 620 |

7 040 |

752 |

6 435 |

31 |

|

1975 |

23 000 |

- |

- |

7 915 |

844 |

6 500 |

34 |

|

1976 |

23 000 |

- |

- |

6 764 |

1 216 |

8 166 |

29 |

|

1977 |

27 000 |

- |

- |

7 760 |

1 702 |

9 776 |

29 |

|

1978 |

19 000 |

- |

- |

(e) 7 596 |

1 767 |

8 873 |

39 |

|

1979 |

22 000 |

- |

- |

7 211 |

2 046 |

9 177 |

33 |

|

1980 |

26 000 |

- |

- |

6 544 |

2 182 |

8 608 |

25 |

|

1981 |

21 000 |

- |

- |

5 717 |

(f) 2 245 |

7 560 |

27 |

|

1982 |

23 000 |

- |

- |

7 225 |

(f) 2 894 |

8 447 |

31 |

|

1983 |

30 000 |

- |

- |

7 203 |

(f) 4 731 |

11 887 |

24 |

|

1984 |

31 000 |

- |

- |

(g) 31 000 |

(f) 71 953 |

168 427 |

100 |

|

Total |

354 000 |

(h) 20 000 |

(h) 100 000 |

119 509 |

94 031 |

273 420 |

34 |

a Sources: New Zealand Forestry Statistics (2000); Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (2001).

b Data for loans and grants from annual reports of the Director-General of Forests unless otherwise stated.

c Sources: Poole (1968); O’Brien (1982). Costs include planting and tending.

d Area planted under grant and loan schemes expressed as percentage of total new private planting.

e Source: O’Brien (1982).

f Sources: Director-General of Forests (1982, 1983, 1984, and 1985).

g This is an anomaly as grants temporarily replaced the previous taxation provisions for forestry companies.

h Totals for loans and grants from McKenzie (1997).

Taxation

In the early 1960s, the government did not see forestry companies as significant actors in the afforestation programme. The tax regime at that time deterred shareholders from re-investing their dividends and profits into second rotations. Being ineligible for the 1960 loans, the companies were provided with a more favourable tax regime in 1965 that made afforestation more attractive to them. This change might have been influenced by the inability to achieve planting targets through more direct incentives to farmers.

Under the Income Tax Act, new forest establishment was encouraged by allowing companies to make current year deductions from assessable income of expenditures incurred directly and indirectly in tree planting. While individuals did not enjoy the same benefit, they could accumulate the costs and deduct them from tax payments at the time of felling. This was known as the “cost of bush”.

Companies that were unable to obtain an immediate tax-saving benefit could receive a tax credit refund of 45 cents to the dollar, in line with an export taxation incentive available at the time. This benefit was not available to companies that already had a Forest Encouragement Grant on the same lands.

To encourage regional investment, forestry and sawmilling were eligible for up to 20 percent depreciation on any plant and machinery used primarily and directly in these activities. The exact level of depreciation was dependent on the priority status of the region as determined by the government in relation to the region’s development needs.

A number of incentives under the Income Tax Act were available for establishing plantations to offset the long gestation period associated with forestry, such as:

Spreading income from the sale of timber over a period of up to five years, including the year of sale. This concession was available only to farmers who planted the trees for agricultural or pastoral purposes, or a woodlot owner whose trees were planted, or maintained, under a forestry encouragement loan.

Individuals depositing forestry income into an “equalization reserve account”. This money then earned interest at three percent and was only taxed when it was withdrawn from the account.

Companies depositing money from thinning operations into an account to be carried forward free of tax.

A number of the tax incentives offered to companies were the same as those that had been offered to individuals in 1949. For several reasons, this time the uptake was considerably better. Firstly, the tax benefits were more important to, and better able to be utilized by, investors than landowners. Secondly, in the 1940s and 1950s, meat and wool farming were very buoyant and timber price controls provided a considerable disincentive. Finally, in the mid-1960s, a range of other incentives also supported the tax benefits.

Mâori leased land

Another option the government selected to facilitate afforestation was land lease arrangements with the Mâori. The Forest Service established and managed forests on Mâori land, and profits were to be shared between the government and the landowners. From 1967 to 1985, a number of leases involved a total of 71 000 ha of Mâori land, with around 51 000 ha planted with trees. From the government’s perspective, the forests were a means of utilizing Mâori land that was otherwise unlikely to be used as productively. The initial leases were for 99-year terms, with the landowners receiving a share of stumpage in lieu of rent. The leases provided for consultation with the landowners and safeguards relating to wahi tapu (sacred) areas. Subsequent leases were for shorter terms with annual rental payments in response to Mâori wishes for greater control. Following this initiative, the private forest industry also entered into lease arrangements with Mâori landowners.

National forestry development conferences

In 1969, the government convened a Forestry Development Conference to assess forest resources and associated industries, and make recommendations for their expansion. The conference served to establish a common commitment to and belief in forestry as a long-term contributor to the economy, and created a sense of partnership between the government and the private sector, both large and small. At this point, the private companies took a much more significant role in afforestation. The conference considered immediate, medium- and long-term perspectives, and reported on efficiencies that could be achieved. Industry, government, the Forest Service and universities were all brought together to contribute to the planning. Export targets were doubled to over 3.7 million m3 by 1973.

Further forestry conferences followed in 1974/75 and 1981. The 1974/75 conference addressed land-use policy, regional development, indigenous forest policy, forest legislation, forest industry, afforestation, short-term wood supply and recreational use of forests. The 1981 conference also addressed a wide range of issues including management practices, utilization, transport, landscape, social and environmental matters.

During the 1970s, public concern over the utilization of indigenous forests grew steadily. The primary concern was clear-felling and burning of indigenous forest to enable conversion to faster growing plantations. A number of new environmental groups emerged. The Maruia Declaration was the largest petition in New Zealand with 341 159 signatures. It opposed an indigenous forest utilization and conversion proposal and was presented to parliament in 1977. The petition received little support from the government, but indigenous forestry became a major political issue. The environmental movement was generally not favourably disposed towards plantation forestry. The conferences were part of the government’s efforts to try to include all relevant stakeholders, including environmental and community groups, in the planning process and to achieve a shared vision for plantation forestry development. The 1981 conference re-affirmed the expansion in the plantation estate achieved and recommended a continuation to 1990 at 43 800 ha per year to complete the goal of an estate with balanced age class distribution.

General export incentives

Two export-focused incentives (not targeted specifically at forestry) - the Market Development Expenditure Scheme and Increased Exports Taxation Incentive (IETI) - were introduced under the Income Tax Act in the early 1960s. Under the IETI, assessable income from the increase in free-on-board (f.o.b.) value of exports over total sales can be reduced. The increase was based on the average of the first three of the last four years’ trading figures. Companies unable to take advantage of the benefit could elect to convert it to a tax credit at the rate of 45 cents to the dollar.

Changes were made to the IETI in 1966 to deduct 15 percent of the increase in export sales over total sales based on the first three of the last five years, and again in 1972 to increase the deduction to 20 percent from the first three of the last six years. Further changes were made in 1975 to raise the deduction to 25 percent and the base to the first three of the last seven years.

Export Development Grants were introduced in 1975 allowing 40 percent tax-free payments towards export development expenditure. A New Market Increased Export Taxation Incentive was also introduced. This allowed a further deduction of 15 percent of the increase in f.o.b. value of export sales if these sales were to new markets. This could be a new product to an existing market, or an existing product to a new market.