"Low value/trash fish" is a loosely used term that describes fish species with various characteristics but they are generally small in size, have low consumer preference and have little or no direct commercial value. The term is not really appropriate in many cases as these fish form the basis of human nutrition in many coastal areas in Asia-Pacific. Fish can be trash for one community but preferred in another, making a precise definition difficult. For this report we first define some characteristics of low value/trash fish and compare usage across a sample of countries.

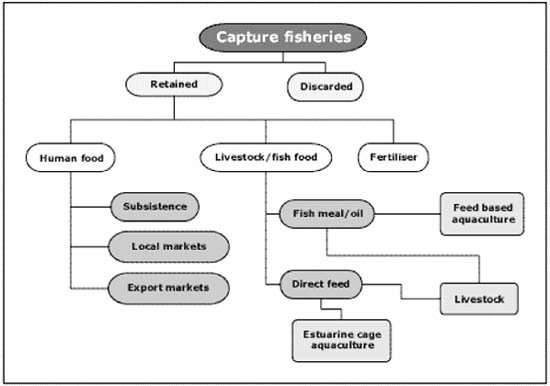

Once caught, fish are either (i) retained or (ii) discarded (Figure 1). Of those retained, they are either used for (i) human food (in a range of product forms and markets), (ii) livestock/fish food (either fed directly to livestock/fish or used indirectly through processing into fish meal/oil that is used to make pellets or (iii) other uses (such as fertilisers).

The use of the terms "low value" and "trash fish" varies across the Asia-Pacific region (see Table 1) and can also change both seasonally and with location. However, in the six countries studied in Asia, low value/trash fish was recognised as being always of low economic value, generally small in size (though it can include larger fish if of low quality or waste from other uses) and having a low consumer preference. They are usually taken as a bycatch[1] (in the sense that it was caught by non-selective fishing gear). A portion is often thrown away or discarded at sea, although this practice is quite minimal in many Asian fisheries.

Figure 1: Major categories of fish in Asia-Pacific

The main difference in use of the term is whether it includes those fish eaten by humans or whether it is restricted only to fish used in animal feeds. In the Philippines and Viet Nam the term refers to fish that is both eaten by humans and used in livestock/fish food (manufactured into fish meal/oil or fed directly to animals). The term trash fish is more restricted in Thailand and China where it only includes the livestock/fish food component. In Bangladesh and India, less is converted into livestock/fish food and it is mainly directly used for human consumption. In China (and to a lesser degree in Viet Nam), it includes a large amount of fish that are targeted for processing into fish meal/oil, for example Japanese anchovy and chub mackerel.

Table 1: Some characteristics of low value/trash fish in six countries in Asia-Pacific

|

Country |

Low value |

Small size |

Low consumer preference |

Human consumption |

Livestock/fish food |

Bycatch |

Target |

Discard |

|

|

Bangladesh |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

+++ |

|

|

China |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

"Trash fish" |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

+ |

|

"Low value fish" |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

+ |

|

|

India |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

++ |

|

|

Philippines |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

+ |

|

|

Thailand |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

+ |

|

| |

"Trash fish" |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

+ |

|

"Low value fish" |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

+ |

|

|

Viet Nam |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

+ |

|

+++ = major discarding (confined largely to shrimp trawling)

++ = moderate discarding

+ = minor discarding

In view of the different uses of the terms in different countries, in this report we refer to all low value fish as low value/trash fish. It was decided to make the definition broad and emphasise that the two different categories of use had to be included in any description of low value/trash fish. The working definition of low value/trash fish is:

Fish that have a low commercial value by virtue of their low quality, small size or low consumer preference. They are either used for human consumption (often processed or preserved) or used to feed livestock/fish, either directly or through reduction to fish meal/oil.

It also noted that inland low value/trash fish share the same issues as marine low value/trash fish but are outside of the scope of this review while recognising their importance as human food, particularly for the rural poor.

It is stressed that it is more important to focus on the issues and types of use for these fish, rather than insisting on a regionally accepted generic term. However, it is important within the region, to use the same term for the different categories of fish that are included under the umbrella term - low value/trash fish. There is an urgent need for a more consistent use of the term. Rather than trying to come up with an agreed definition, all countries should record low value/trash fish under their categories for use, i.e.

(i) discards

(ii) human food (fresh/dried/preserved/value-added products etc.)

(iii) direct feed for livestock and fish (separate categories)

(iv) fish meal/oil

(v) other (e.g. fertiliser)

A fuller description of the use of the term low value/trash fish in these different countries is given below. Further insight into the species composition, production trends and use is given in Sections 2.1 and 2.2.

Bangladesh

Low value/trash fish in Bangladesh is low-value fish caught as bycatch from small mesh drift nets - a gill net (that targets hilsha fish); large mesh drift (that targets Indian salmon) and shrimp trawl with its twin rig trawl (that targets shrimp). Some of the bycatch is commercially valuable fish (by-products) while others are less valued and do not have a specified use. However, in the Bangladesh context, any fish has a value and, with the exception of the shrimp trawl fishery, almost all the fish species are landed and are consumed locally.

China

China has a rather detailed ecological and economic description of "trash fish", which explicitly states that it is fish "not suitable for direct human consumption". "Low value fish" refers to those eaten by humans. The nature of China’s fisheries is such by small pelagic species, some of which have potential economic value if not caught as juveniles. More recently, fish that were once considered "trash" and were discarded at sea (such as Japanese anchovy and Chub mackerel) have become target species in trawl and purse net fisheries as a result of fisheries resources overexploitation and the increasing demand from aquaculture, which provides a ready market for these species. This has become a common trend in several of the countries covered by this review.

Low value/trash fish generally comprise fish with small body sizes (with relatively low flesh ratios) and low economic values. They often decay more easily than the other more valuable fish and are very vulnerable to mechanical damage. Under normal weather conditions, they deteriorate and lose further processing value before they are landed.

India

The term low value/trash fish is often used in different ways throughout India and some confusion exists on what it actually means. It is often used interchangeably with the term bycatch. A case in point is bycatch from shrimp trawls, where the ratio of target species to the bycatch may be as low as 1 to 20. This incidental catch includes several species of fin and shellfish, which have varying values in the market. Those fish, by virtue of their small size or low consumer preference, have either little or no value and are therefore called low value/trash fish. In some fisheries a proportion of this low value/trash fish is discarded overboard (often to make space). Even within the landed catch there are some species whose size, appearance, and consumer preference constrain them from being readily accepted as human food. In general, prices can be used as criteria for considering fish as low value/trash fish (e.g. fish fetching less than $0.10 per kg).

Fish may be considered as low value/trash fish in one season but not so in another season and may be considered as low value/trash fish in one region but may find consumer acceptance elsewhere, and hence possibly not considered as trash.

Philippines

The term trash fish or "dyako" in local dialect has been used since the trawl era in the 1950s to refer to the lowest category of trawl-caught species. It is the least valued fish group mainly composed of juveniles of commercially important food species, as well as lesser known food species (both young and adult). In the present context, commercially-important food fish landed by pelagic fisheries that are spoiled and/or damaged (due to rough handling and poor post-harvest practices) that could still be used for industrial purposes are also considered as low value/trash fish.

Thailand

Trash fish are defined as those used for livestock/fish feeds, the majority being used for fish meal/oil. "Low value food fish" includes the very extensive use of fish for processing for human food in artisanal fisheries throughout Thailand. "True" trash fish is used for those species that are small in size even when they mature. However, juveniles of high value marine fishes make up a significant proportion of the total trash fish. Thai people refer to trash fish as "Pla ped", which literally means "fish for ducks", most likely because the fish have been traditionally used to feed ducks and other livestock. With the emergence of coastal cage-fish aquaculture, this fish is now increasingly diverted to aquaculture.

Viet Nam

In general, trash fish in Viet Nam is only bycatch. However, it is the most important fish product in terms of both weight and value. Trash fish is caught mainly from trawling for higher value fish, crustaceans and molluscs. There are many trash fish species, the composition of which depends on the fishing area and the type of gear. There are three categories and terms for trash fish in Vietnamese: trash fish, trawling fish and "pig fish", the latter being the lowest quality and therefore having a more restricted meaning than the other two terms.

The identification of trash fish is not always clear. Previously it was fish of low or no economic value but such fish are now being converted into value-added products. Leatherjacket is a very bony fish, which was rarely eaten before the development of processing technology. It was either only salted and converted into fish sauce, or even used as a fertiliser in southern Viet Nam. Recently, a process was introduced involving drying it for export and now it has economic value and is not considered a "trash fish". Pony fish also used to have a low value but now it is used to feed grouper, cobia and other species, and its value is increasing.

The fisheries sector in the Asia-Pacific region can generally be divided into:

1. large-scale industrial/commercial subsector; and

2. small-scale artisanal subsector[2]

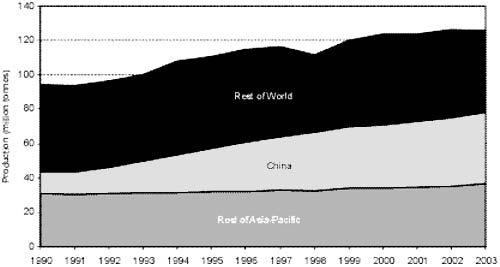

In 2003, total world fishery production was reported to be 136 million tonnes, representing an increase of some 30 percent since 1990 (Figure 2). Marine capture fisheries production was 85.9 million tonnes in 2003 (FAO, 2005). In 2003, capture fishery production from Asia-Pacific accounted for half of world production, and the production from aquaculture reached almost 90 percent of the global aquaculture production of fish and shellfish.

Figure 2: World fishery production (million tonnes)

Source: FAO (2005) and FAO database.

In 2003, of the 20 top producers of marine capture fisheries, 10 were from the Asia-Pacific region (Table 2).

Three factors differentiate fisheries in the region from larger-scale temperate fisheries:

1. The dominance of small-scale fisheries, with most operations lasting from a day to a few days, irrespective of the economic value of the catch;

2. The tropical characteristics of the ecosystem, with individual species having a relatively small stock size compared to those in temperate waters. As a consequence, fishers use a large number of gears and depend on a larger number of species for their livelihoods; and

3. The inherent flexibility of markets, since these are based on a long tradition of consuming a wide range of catch species, each in relatively small volumes and using extremely diverse local processing techniques.

Table 2: Marine capture fishery production 2003 (million tonnes) - Top 10 producers in Asia-Pacific

|

Country/Province |

Production |

World ranking |

|

China |

14.294 |

1 |

|

Japan |

4.536 |

4 |

|

Indonesia |

4.350 |

5 |

|

India |

2.912 |

8 |

|

Thailand |

2.620 |

9 |

|

Philippines |

2.037 |

11 |

|

Republic of Korea |

1.641 |

13 |

|

Viet Nam |

1.535 |

14 |

|

Malaysia |

1.283 |

16 |

|

Taiwan Province of China |

1.132 |

17 |

|

Subtotal |

36.34 |

- |

|

World total |

85.88 |

- |

|

Share of Subtotal/World |

42.3% |

- |

Source: FAO (2005) and FAO database.

According to official statistics, production in a number of Asia-Pacific fisheries peaked in the last two decades and is now stable or declining, depending on the area being fished. Highly intensive fishing, especially in trawl fisheries, targeting shrimp and other demersal species has also led to a change in catch composition. The share in landings of fast growing and short-lived species and the catch of small-sized juveniles of commercially important fish species is steadily increasing (so-called "fishing down the food chain"). There is also evidence (e.g. Gulf of Thailand) that the abundance of species at higher levels in the food chain has seriously declined with a resulting higher risk to biodiversity and increased vulnerability of fisheries. There is little doubt that the quality of stocks has deteriorated faster than the volume and value of fish caught. However, it appears that many fisheries remain financially viable due to strong market demand and low opportunity cost of attracting labour into the fishing profession.

Small-scale artisanal fisheries are typically labour-intensive fishing activities, often carried out as one of several income-generating activities. Small-scale, coastal fishing operations have been estimated to account for as much as 75 percent of the total fish catch from the region, although there are no really firm data on this. Regional variations to this figure obviously exist, for example, it is noted in FAO (2001) that some 88 percent of the demersal catch of 0.86 million tonnes in the Gulf of Thailand is taken by medium or large-sized industrial trawlers (i.e. vessels larger than 14 m in length). Catches from small-scale fisheries are regarded to be under-reported in many cases and the overall impact of small-scale fishing activities is not always appreciated. Conversely, industrial vessels represent only a small proportion of overall catches, although their impact on fisheries is more easily monitored and regulated through various administrative and technical means (e.g. vessel registration, gear restrictions, zoning, etc.).

In terms of involvement of people (employment and coastal livelihoods) of the countries covered by this review, the fisheries sector is dominated by small-scale fisheries. Hence, managing the industrial and small-scale fisheries that mostly target coastal fisheries resources needs to take into account both the social, economic and cultural considerations as well as the biophysical and ecological factors. The management of fishing capacity is generally addressed in relation to three key issues now affecting Asia-Pacific fisheries: declining resources, coastal degradation, and the threat of increased poverty in fishing communities.

Subsistence fishing[3] still exists in some countries, although this is often confined to freshwater capture fisheries. The bulk of marine fisheries catch is sold, either in local or export markets (i.e. a "cash crop"). Thus, in addition to providing full-time and part-time employment to millions of people directly or indirectly involved in fishing, fisheries contribute to foreign currency generation.

Bangladesh and India

Small-scale artisanal and coastal fishing are important livelihoods in Bangladesh and India. Bangladesh reports about 1.2 million people engaging in full-time fisheries and another 10.2 million part-time fishers. The artisanal fishing sector contributes more than 90 percent of total fisheries landing in Bangladesh. There is almost the same number of non-mechanised and mechanised boats in Bangladesh, both adding up to a total of about 44 000 units. The main fishing gear is gill net, which contributes more than half of the catch, about 37 percent of which are hilsha (Tenualosa ilisha), a pelagic fish that school in coastal waters and migrate up river to spawn.

In India, there are about 1.45 million fishers, and another 10 million people in fishing related business, including processing and marketing. Fishing is conducted from traditional fishing crafts, motorised boats (most converted from traditional boats) and small mechanised boats. The mechanised fishing fleet contributes about 68 percent of the total marine landing. Common gears used are hook and lines, gill nets and boat seines. About 70 percent of landing comes from the west coast (Arabian Sea), and the rest is from the Bay of Bengal.

About 25 percent of total marine fisheries landing in India consist of demersal species, mainly caught by trawling. The rise in motorised and mechanised fishing gears and the increasing number of offshore fishing vessels is being driven by estimates of potential growth in demersal fishing in these waters. In contrast, the trawl fishery is relatively small in Bangladesh. A total of 80 trawlers were in the fleet in 2002, 44 are shrimp and 36 fish trawlers. Despite this, trawlers contribute about 30 percent of total fisheries landings and the number of large vessels being purchased by fishing companies is increasing.

China

About 1.2 million people are directly engaged in fishing in China and another 280 000 people in processing and marketing. There are about 280 000 small fishing vessels in the marine fisheries. Gears used include trawls, fixed nets, small-scale drift nets, purse seines and other gears. Trawl fishing (both otter trawls and pair trawls) contribute about 45 percent of total landing, with the rest caught by small-scale fishing gears and off-shore pelagic gears. Trawls are used to catch demersal species such as croakers, with the dominant species being the largehead hairtail. There is a large fishery that targets Japanese anchovy and juvenile chub mackerel to supply a large part of the fish used for livestock/fish feed.

Philippines

The Philippines splits the marine fisheries sector into "municipal" (small-scale, using vessels of three tonnes or less) and "commercial" (using vessels weighing more than 3 tonnes) types. Despite this separation the municipal fishing sector clearly consists of commercial fisheries (i.e. catching fish that are destined to be sold). Municipal fishing takes place in inland or coastal waters, using either fixed gears or small vessels, and employs more people (about 676 000 persons) than commercial fisheries, although it contributes only 25 percent of total marine landing. Many gears are used by this sector including gill nets, hook and line, beach seine, fish corral, ringnet, baby trawl, spear and longline. Purse seine, targeting pelagic fish such as round scad, Indian sardines, frigate tuna, skipjack, etc., contributes about half of the entire commercial landing.

Thailand

There are about 57 800 marine fishing households in Thailand, most of which engage in small-scale fisheries. Vessels less than 14 m in length are considered small-scale. In such households, most family members, including women, are involved in fishing, using mainly shrimp trammel nets and crab gill nets or fish traps.

Rapid development of the industrial trawl fishery took place in Thailand in the mid to late 1960s, followed by Malaysia (early 1970s) and then Indonesia. In Thailand, this development meant a tripling of the number of otter board trawls, pair trawls and beam trawls within a period of ten years. By 1989, the number of Thai trawlers peaked at about 13 100 boats. Adding to this was a small number of push nets that targeted demersal fishes. The catch per unit effort declined from over 300 kg/hour in 1963 to about 50 kg/hour in the 1980s, and 20 - 30 kg/hour in the 1990s. This was accompanied by a decline in mean trophic level of catches in the Gulf of Thailand (Pauly and Chuenpagdee, 2003).

Fishers and their families in the Asia-Pacific region are often considered to be among the poorest of the poor. These families often have small land parcels unsuited to agriculture or are landless occupying marginal coastal lands. Often the only significant possession is the fishing vessel that supports their livelihood. This is closely linked to their high exposure and vulnerability to accidents, natural disasters and other shocks.

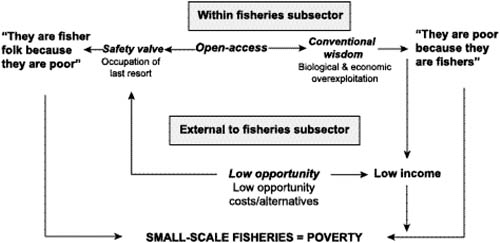

This raises the issue of whether fisher folk are poor because they are fishers or whether they are fishers because they are poor. These two paradigms are shown in Figure 3. The first paradigm in Figure 3 is called conventional wisdom and relates to the open access nature of fisheries that allows more and more people to enter the fishery which, because of the "tragedy of the commons" leads to biological and economical over exploitation of the resource, the dissipation of rent and finally impoverishment of the fishing community. This is the classical Malthusian concept of poverty: over exploitation of the resource results in low catch, which equates with low income and poverty. From this perspective, therefore, the problems lie solely within the fishery sector itself and the solution is better fisheries management.

The second is the low opportunity paradigm. Poverty is explained by using the concept of low opportunity incomes due to the lack of alternative incomes outside of the fisheries sector that drives (or keeps) fishers’ incomes at a low level. Thus the the solution is to improve the economic situation outside the subsector. In this scenario, it is important to note that a small-scale fisheries subsector is extremely mobile, with people moving into and out of fishing, both seasonally and over longer time scales, depending on the relative attractiveness of other activities compared with fishing at any given time.

Linking these two paradigms creates the perception that fisheries, because of its "open-access" nature, as well as lack of alternative opportunities, often offer employment of last resort. Some see this safety valve aspect of small-scale fisheries as a desirable aspect and not necessarily an undesirable attribute as espoused by the conventional wisdom. All these arguments, however, all end up with the same conclusion that "small-scale fisheries = poverty".

Figure 3: Relationship between small-scale fisheries and poverty as conceptualised in the literature (redrawn after Béné (2002))

There are considerable difficulties in, firstly, defining who is a fisher and, secondly, what is a fishing community. There is added complexity in measuring poverty in small-scale fishing communities, but despite these difficulties FAO (2002c) has estimated the number of income-poor, small-scale fishers worldwide. Estimates suggest that 5.8 million (or 20 percent) of the be small-scale fishers, earning less than $1 per day, the majority of which live in the Asian region. These estimates exclude aquaculture activities. Related activities, such as boat building, marketing and processing, may involve a further 17.3 million income-poor people. These figures suggest an overall estimate of 23 million income-poor people, plus their household dependents, relying on small-scale fisheries, predominantly in Asia (Table 3). It is also probably fair to say that these figures are underestimates.

Table 3: Poverty in Asian small-scale fisheries (1 000 people)

| |

Asia |

World |

Share of Asia |

|

% of population on < $1 per day |

25.6% |

- |

- |

|

Income-poor fishers |

4 821 |

5 759 |

- |

|

Related income-poor jobs |

14 464 |

17 278 |

- |

|

Total income-poor |

19 286 |

23 037 |

84% |

Source: FAO (2002c).

Many countries have committed themselves to gradually introducing rights-based fisheries management systems for regulating access to coastal and marine resources. This process is planned to go hand-in-hand with the decentralisation of fisheries management authority and functions to subnational administrative levels, increased participation of the stakeholders and the introduction of co-management. It is assumed that the closer the small-scale coastal fisheries management authorities are to resource users, the better they can accommodate specific socio-economic, political and ecological local characteristics into their particular management systems.

Despite this move towards rights-based fishery, there is still a need to resolve the multiple objective framework of management policies on national and regional levels. Policy goals can often be contradictory and inter alia include:

reduction of user conflicts;

increase in fish production;

safeguarding employment and incomes;

resource sustainability;

expansion of aquaculture and offshore operations; and

export promotion.

Although many countries have their own policy, legal and institutional or regulatory frameworks to manage their respective fisheries, these systems are generally based on short-term objectives and goals such as increasing production levels, rather than the long-term comprehensive and sustainable management of fisheries (Vichitlekarn, 2004). In the long run, policy-makers and managers will have to realise that trade-offs will be required to meet the priorities for the country, and priority objectives will have to be agreed.

|

[1] The term "bycatch" is a

generic term referring to catch that is incidental to the target species, noting

that in many fisheries using non-selective gears, such as fish trawls, the term

is sometimes used interchangeably for the unwanted portion of the catch that is

discarded or sometimes to refer to the less desirable fish that are landed, i.e.

low value/trash fish. [2] Examples of how these two subsectors are defined in several different counties are given in Appendix 1. [3] "Subsistence fishing" as the term is used here, refers to fishing activities where the catch is largely used for home consumption and is not substantially traded. |