The green bay mussel, Perna viridis, is cultured by the floating raft method about 800 m from the shore in the waters off Johore Bahru, Malaysia. The narrow strait separating Peninsular Malaysia from Singapore has a depth of 2 fathoms (3.66 m) at low tide and 4 fathoms (7.33 m) at high tide. The culturist owns 10 rafts and works it himself with the help of his wife, 2 children and a watchdog. They live in a raft house constructed at a cost of M$l 000. This is attached to the mussel rafts. They also have a M$2 000 3-year old boat with an 8-Hp outboard engine.

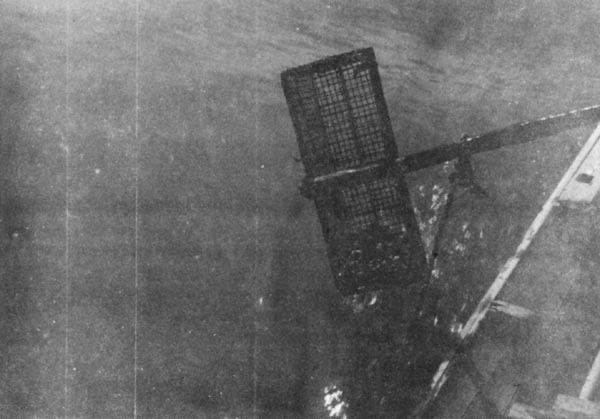

Each raft measures 6.1 m × 6.1 m. It consists of a rigid lattice-like framework of wood planks spaced 15" (38 cm) apart and supported by 15 equally spaced styrofoam floats. From the framework are suspended 250 3-m long weighted ropes made of twisted old nylon fishing nets. These are spaced 38 cm apart. The mussel spats attach themselves to and grow to marketable size in these ropes. Each plank frameworks costs M$200, each styrofoam float M$25 and the improvised ropes M$0.30/ft (30 cm) (US$1 = M$2.35).

One to two months after the weighted ropes have been put in place, mussel spats appear. These are allowed to grow up to 8 months when they reach 6 cm-10 cm in length. They are then ready for the market.

Each rope produces 50 keti (1 keti = 600 g) of mussels. The operator harvests the mussels depending on the specific order of a buyer who comes and picks it up. The wholesale selling price is M$0.20/keti. A raft with 250 growing ropes may therefore produce a maximum of 12 500 keti of mussels worth M$2 500. With a life period of 3 crops (8 months each), it . would produce a maximum of M$7 500 before it is totally replaced.

In the 5 years that the operators has been culturing mussels, the project has not suffered any loss to poachers. However, he suffered the loss of all his spats in October 1981, due, he believes, to the long period of rain which lowered the salinity of the water and also brought polluted water from a textile mill and a pineapple canning factory situated about 5 km away on the Singapore side of the strait.

Estimate Cost of a 10-Raft Mussel Project

(US$1 - M$2.35: 1 keti = 600 g)

| A. | Capital costs | ||

| 10 rafts (6.1 m × 6.1 m) = M$l 475 each | M$14 750 | ||

| 1 floating house | 1 000 | ||

| 1 small boat with 10-Hp engine | 1 200 | ||

| Miscellaneous equipment (knives, baskets, (flashlight, lamps, etc.) | 300 | ||

| Sub-Total | M$17 250 | ||

| Contingency 5% | 863 | ||

| Total Capital Cost | M$18 113 | ||

| B. | Operating expenses | ||

| Miscellaneous operating and contingency expenses (minor repairs, gasoline, oil) | M$ 500 | ||

| Total Budgetary Outlay | M$18 613 | ||

| C. | Estimate gross sales | ||

| (90% recovery, 2 500 growing ropes/10 rafts, production - 50 keti/rope, wholesale price-M$0.20/keti) .9 × 2 500 × 50. × .2. | M$22 500 | ||

Based on the above, the net proceeds for three 8-month crops (2-year life of rafts) would be as follows:

| Crop/harvest | Gross sale | Sinking fund* | Net |

| 1st | M$22 500 | M$6 827 | M$15 673 |

| 2nd | 22 500 | 6 827 | 15 673 |

| 3rd | 22 500 | 6 827 | 15 673 |

The Indonesian Government has a mussel project that it constructed for experimental and demonstration purposes in Banten Bay, District of Serang, Indonesia. The project has 3 rafts, each measuring 8 m × 8 m. A raft is composed of 27 bamboos arranged in a trellis with 17 along one axis and 10 across it. Ten steel drums serve as floats. From the rafts hang 3-m long growing ropes, spaced 1-m apart, around which the mussel spats are attached. To each rope is tied a 5-k concrete weight which keeps the former in a vertical position. The rope is made of old netting wrapped around a core of new rope. The whole project cost the government RP 1.7 million.

The project site is protected from big waves by an island, Pulau Tarahan. The low tide/high tide difference in the bay is 1 m.

The project was started in 1979 and has been producing continuously since. Each growing rope produces 25–30 k of marketable mussels after six months of growth.

The most interesting fact about this project, however, is that the site did not use to produce mussels. The mussels here are the progeny of spats, 2–3 cm, originally from Tangerang, 75 km away, and transplanted to the site by the Indonesian Government's fishery personnel. There are now a number of privately-owned mussel rafts in Banten Bay and many more fisherfolk planning to put up their own projects. This activity is worth evaluating after a few years of successful operations.

The shellfish commonly known as cockle, Anadara granosa, is cultured in the waters off Kuala Juru in Penang, Malaysia. The area comprises 200 acres (1 acre = 4 047 m2 ; 1 ha = 2.47 acres) of shallow waters leased from the government for M$10/acre/year on a year-to-year basis. The concession is owned and operated by an association of 65 fishermen organized in 1975. The association collects the cockles with 59 boats. Nine of these are big 30–35 footers with reconditioned 10 Hp, 2 cylinder inboard engines costing a maximum of M$4 000. The other 50 boats are smaller with single cylinder 6–9 Hp outboard engines.

In practice, the boats go out daily to the concession area and collect cockles during the high tide period. The collecting period lasts a minimum of 2 hours. The big boats use up a gallon of fuel per hour. The smaller boats use less.

The concession site, the fisherman puts his boat in low gear and arranges the rudder into a fixed position to allow the boat to travel in a circle with a diameter of roughly 30–40 m. As the boat slowly moves in a clockwise direction, the gatherer stands at the boat's starboard side and dredges the mud bottom with a cockle collector attached to a long pole. Every now and then, he lifts the dredge from the bottom, shakes it in the water to wash off the mud, pours the caught cockles onto the deck and then resumes dredging the bottom.

The boats are able to dredge and collect 3–5 sacks/boat/high tide. A sack weighs 120 keti. The association collects an average of 100 sacks/day. However, production may go down as the season ends. In good years, the season sometimes lasts all year round. For every sack of cockle landed, the fisher-man is temporarily paid M$5 by the association.

The association provides the fishermen with the following services and facilities: a landing site, a working shed, sacks for the cockles, stevedoring, a general store, etc., and at times, credit for the repair of their boats and for other personal purposes.

The association also sees to the washing and the cleaning of the shellfishes collected until all mud, impurities, dead and empty cockle shells are removed. Workers, mostly old women and young children, are paid M$2 per sack of cleaned and sorted cockles.

The association sells the cockles to wholesale buyers who regularly come to the kampong. The cockles are sold for M$17-M$18/sack of 120 keti. The association shoulders the loading expenses of M$0.50/sack. Payment is sometimes made in cash on the spot but the general practice in the area is the time-honored consignment basis. In the latter case, payment is usually made after 10 days. Due to past experience, the association limits its consignment sales only to buyers with good credit standings. In some instances, it requires consignment buyers to deposit M$12 000 in an account with the association. The amount is good for 10 days of daily purchases.

At the end of the season or earlier, as decided by the members, the association distributes dividends. Only a small part of the profits are retained for future operations and other needs. Since records of all transactions are meticulously kept, there are usually no complaints from the members.

The foregoing is a good example of what proper control can achieve to conserve a natural resource and prevent its premature depletion. The Government's initiative and the technical aid it extended in all aspects of operations including conservation,' storage, marketing, organization of the association, etc., was a big factor. It generated a reservoir of enthusiasm among the association members and engendered a very strong cooperative frame of mind. Almost always, the cooperation of the fishermen-beneficiaries themselves is the crucial factor in the success or failure of any conservation programme. The concession started being exploited profitably 7 years ago. With the existing conservation measures and the cooperation of all concerned, it bids well to continue providing a profitable source of income for many more years to the fisherfolk of Kuala Juru.

Cockle farming in Malaysia

Manual dredge to collect cockles

Cockles harvested from culture beds

Mollusc culture in the Philippines showed significant growth rate of over 120 percent annually in the last four years (Csavas, 1985). Oysters made up for 55 percent and mussels 45 percent. This remarkable performance is due to the rapid transfer of improved technology. The traditional stake method of mussel culture produce 20–68 tons/ha/year while the rope or hanging method yield about 300 tons/ha/year.

The profitability of oyster and mussel farming in the Philippines using different methods are summarized in Table 10,

Table 10. Costs and earnings of oyster and mussel farming1

| Oyster culture method | Mussel culture | |||||

| Stake | Hanging | Lattice | Broadcast | Stake | ||

| Average farm size (m2) | 1 603 | 5 968 | 472 | 3 678 | 3 242 | |

| Capital investment | ||||||

| Per farm |  400 400 | 800 | 203 | 111 | - | |

| Per ha | 2 496 | 1 340 | 4 301 | 302 | - | |

| Total annual receipts | ||||||

| Per ha | 8 942 | 18 934 | 19 001 | 1 556 | 12 975 | |

| Total annual expenses | ||||||

| Per ha | 5 711 | 4 975 | 9 559 | 1 408 | 5 765 | |

| Net annual earnings* | ||||||

| Per ha | 3 231 | 13 419 | 9 442 | 148 | 7 210 | |

| Earnings on sale (%) | 36 | 73 | 50 | 10 | 56 | |

There are no studies conducted in the Philippines on the quality on oyster and mussel areas. However, investigations conducted elsewhere (Cheong, 1985) may be used as reference. Findings showed that grounds suitable for mussel farming should have phytoplankton concentrations of 17–40 micrograms chlorophyll-a/1 of seawater; 0.17–0.25 m/sec water flow rate at flood tide; 0.25–0.35 m/sec water flow rate at ebb tide; and primary productivity ranging from 73–100 microgram carbon/m3 .

* Includes unpaid family labor.