There are many certification schemes and branding initiatives of relevance to the marketing of capture fisheries products. Certification initiatives may involve assessment of the fishery itself as well as certification of the supply chain, known as chain-of-custody certification. In addition, some certification initiatives use product labels, while others do not. Equally, some labeling/branding schemes do not require formal certification. Labels, seals, or logos are used to give consumers more information about the provenance, production methods, or environmental friendliness of the product (or company). All labels are intended to inform the consumer, but not all labels have the same influence. They range from the strictly regulated and third party certified use of labels to self-assertions made by individual companies to promote their own products. They also cover a huge range of topics including the environment, social justice and the quality of products.

It is important therefore to distinguish between environmental certification, social certification and branding in fisheries, all of which are covered in this paper.

Environmental certification examines the level of sustainability of fisheries exploitation and is generally restricted to environmental issues, such as the maintenance of fish stocks and the ecological impacts of production, rather than any wider coverage of socio-economic issues, although some environmental certification schemes do include some social issues. Furthermore some environmental labels might be restricted to certain key issues such as reducing marine mammal bycatch, rather than a more comprehensive assessment of the fishery and its impacts. Environmental certification rarely guarantees the quality of certified products, just their provenance. Certification generally implies that producers conform to a certain set of standards and that they are regularly audited against these standards by a third party verification body.

Social certification examines the social provenance of products, mainly in terms of the social/working conditions of those producing the fish and fish products; and/or whether they receive a fair price.

Brands/branding allows a producer to promote certain qualities of a product that are often purported to be unique or otherwise sought after. As a result, environmental and social certification schemes can therefore be considered forms of brands/branding.

There are a number of environmental certification initiatives. A list of these initiatives are given in Appendix E which presents information on initiatives for global third-party fisheries certification and some information about International Standards Organization (ISO) certification, i.e. voluntary initiatives with which APFIC countries/companies could actively engage — should they wish to do so. The table shows clearly that except for the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and the Friend of the Sea schemes, there are currently few options for voluntary environmental certification of marine capture fisheries, especially as the ISO provides certification of companies and would not represent certification of fisheries management per se.

In 2005 FAO prepared a series of guidelines on the ecolabeling of fish and fishery products from capture fisheries. These guidelines were intended to cover principles, general considerations, terms and definitions, minimum substantive requirements and criteria and procedural and institutional aspects of voluntary, third party certified ecolabeling initiatives. At present, it would appear that the only such fisheries-specific scheme that adheres to these guidelines is the MSC Responsible Fisheries Scheme.

Other environmental schemes and initiatives in Appendix E include:

Only a very few social certification/initiatives involve, or have involved, fisheries. Appendix F presents information on global social certification schemes and initiatives and also provides reference to some specific schemes where previous or potential involvement with fisheries has been reported.

In addition to the schemes mentioned in the appendix, it should also be noted that many supermarkets in developed countries include some social aspects in their traceability audits and assurances from suppliers about products being sourced from companies engaged in fair social practices. In addition the MSC certification scheme includes some social issues, but such issues are not an integral or especially important part of the certification process.

This publication considers branding only, as opposed to generic product promotion. The difference between the two is that "brand" promotion is undertaken by an individual firm, group of firms, or even by a country, with the aim of growing the market for its brand, i.e. to increase its sales by diverting existing consumption from competing brands and by stimulating additional consumption. In the case of country branding this would involve trying to increase the market share in overseas markets.

Generic promotion on the other hand refers to activities undertaken by an industry or group to promote benefits that relate to a whole sector or category rather than to specific brands, for example, "drink more milk", or "eat more fish". Its purpose is to benefit demand for the industry — to "grow the size of the pie" or "slow the shrinkage of the pie" (Tveteras et al. 2006). It should be recognized that branding is just one aspect of product promotion. However, having made this distinction, it should also be noted that country

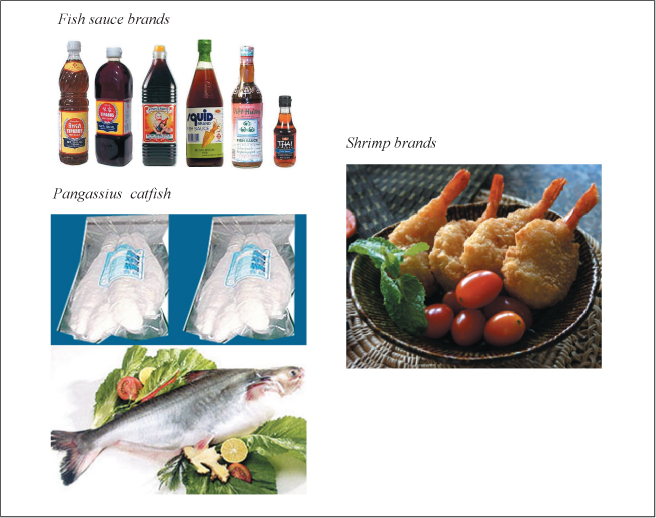

Figure 1: Some examples of branding of fish products in Asia and the Pacific

or regional branding is something of a combination of both brand promotion and generic promotion, and may be used to both expand market share, and increase the size of the market.

As noted at the APFIC forum in Malaysia in August 2006 (Subasinghe 2006), branding is important in adding value to fisheries products and creating consumer awareness about products. Some branding schemes are specific to fisheries, while others are wider in their scope and cover both fisheries and non-fisheries products, as discussed hereunder.

|

Branding can involve both third-party certification and own-brands. Branding a product can be used to convey many messages to consumers, including issues related to aspirational qualities, environmental issues, quality and the provenance/source of products (i.e. a particular company, a region or a country). Self-declared ecolabels not involving certification or third-party assessment can also be thought of as a form of branding, for example the pesticide-free label in Thailand (Figure 2). Typically, however, guarantees or implications of good quality are often paramount in branding exercises, as it is through such an emphasis that producers/retailers attempt to capture the market share and add value through generating price premiums. |

|

|

In Japan1 the Japan Agricultural Standard (JAS) Certification System allows various agricultural commodities, including seafood products, which comply with the standards specified for each product, to bear the quality label — the “JAS” mark. The JAS standard consists of two different standards, the “quality” (the standard of the agricultural, forestry and marine products) and the “display” (which demands the display of the descriptive label standard, the history and the quality). For the sake of consumers, a descriptive labeling standard was specified in 2000 for all kinds of food and drinks. The “JAS’ mark is considered a descriptive label quality standard rather than a quality specification of the product, and is mandatory for exports. In addition, there is a Frozen Food Processors Registration system, managed by the Japan Frozen |

|

|

Foods Association, which accords registration to frozen food processors who produce food products with a high level of quality and safety for domestic as well export marketing. The association has more than 2 000 registered members on its roll. |

|

|

In Republic of Korea, to secure food safety and to harmonize with international standards of food quality, the government enacted the “Fishery Products Quality Control Act” in 2001; an HACCP mark is approved for use by the Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) and the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF). |

|

|

Also in Republic of Korea, the National Fisheries Product Quality Inspection Service |

|

|

(NFPQIS) has three categories of certification for fisheries products accredited by the government: “Fisheries Product”, “Special Fisheries Product” and “Traditional Fisheries Product”. This certification scheme issues the certification document and a mark for each category to be used on the product. The accreditation marks are not only for quality control purposes but also for preserving and promoting traditional fisheries products in the food market. They have not been very successful. In recent years provincial certification schemes (each with different inspection guidelines) for provincial producers to use in the national market have been more active and successful. Outside Asia, an interesting branding exercise |

|

|

has been initiated by line fisherfolk in Brittany in France.2 This scheme is not based on environmental issues, but uses a label, and is based around the concept that the label provides the consumer with |

|

__________

1 Text adapted from Synthesis paper on fisheries certification in Asia–Pacific presented at the APFIC meeting in Bangkok, 30 March 2007.

2 http://www.pointe-de-bretagne.fr/assoc.php

|

traceability information about the individual vessel that caught the fish, fishing methods, etc. It also strongly focuses on sanitary and quality aspects of the products. Other examples of quality brands in the European Union include “Quality Approved Scottish Salmon”, and Label Rouge in France3 (the latter not specific to fisheries products). In addition, many supermarkets in the EU have their own private labels to designate a range of product qualities they deem favourable to consumers. |

__________

3 The Label Rouge program (www.label-rouge.org/) focuses on high-quality

products, mainly meat, with

poultry predominating. It emphasizes quality attributes such as taste, culinary qualities,

free-range production and food safety. It

is not an ecolabel as such, except to the extent that good environmental practices and low

stocking densities translate

into better product quality. It is underpinned by criteria such as husbandry techniques, use of medicines, feed types, shelf life and transportation times and incorporates a full traceability system. It uses third

party certification and a label.

Label Rouge poultry accounts for over half of all consumer poultry purchases despite retail

prices double those of

standard poultry.