Highland development, while seen as increasingly important, has not been integrated into mainstream development policies. Delayed by the difficulty in access, communication barriers, frequent migration of hill tribe people and, to a certain extent, alleged illegal dealings among the hill tribes, assistance to highland communities has faced insufficiencies in many respects. Consequently, present support activities are unable to appropriately respond to the vulnerable circumstances (geographical remoteness, delayed land settlement, economic difficulty, socio-cultural and environmental degradation and legal problems) of hill tribe people.

Each government agency described in the second chapter sets its policies concerning assistance to hill tribe communities. The implementation of the policy-based programmes for the benefit of communities is a crucial issue. This chapter will analyse the factors with implications for field-level implementation of policies from the perspective of (1) participation of and communication with communities; (2) local curriculum development; (3) local capacity building and (4) inter-organizational collaboration.

Communication with and participation of hill tribe people are among the most essential factors in promoting education and learning opportunities so that they reflect the needs of highland communities. This is particularly important in the current decentralization process, where budgets allocated to government ministries are declining and those to communities are increasing. To date, however, participation of and communication with hill tribe people (such as the decision-making and communication for highland development) seem to be limited. This is due to a number of factors.

First, for those working in support of hill tribe communities, distance to villages is a major obstacle. Hill tribe people traditionally prefer to live in small villages rather than being integrated into large communities. It is extremely difficult to extend services to a large number of these widely scattered villages, as it requires a high investment in terms of personnel and financial resources. Besides, many hill tribe people in Thailand and in neighbouring countries continue to migrate from one location to another regardless of national borders. Thus, there still remains a large area not covered by service agencies.

Second, the fact that hill tribe community support is not yet integrated in the mainstream development efforts of the Thai government limits the possibility of enhancing services to meet the needs of hill tribe people. In agriculture and rural development for example, which has a major impact on the livelihood of hill tribe people, participation of farmers (particularly small farmers) and local agricultural communities has not been facilitated in the decision-making and plan formulation processes. Agricultural services and infrastructure have catered to the needs of "progressive" farmers more than to small farmers'55. Another example is radio broadcasting in hill tribe languages, which was originally initiated as a response to imminent communist presence in hill areas. To mitigate the communist influence, the Thai government broadcast its highland development policies through radio. With this historical background, the role of hill tribes in the process of radio broadcasting has remained passive and limited, even though the allegation of hill tribe involvement in communist activities has subsided. Advocates argue that tribal language radio programmes should now be developed as part of the mainstream modern communication network in the unified Thai nation56.

|

Radio programmes have been offered to hill tribe people in each tribal language one or two hours daily. Tribal people hope longer hours of broadcasting. Also, often the hours of broadcasting are very early in the morning or coincide with the hours of farming. The subjects covered include agriculture, community relations and life skills. DNFE uses radio as a medium for distance education. In areas where communities have access to DNFE CLCs, the role of radio is declining, while in most areas not accessible to CLCs, radio programmes remain an important source of information and knowledge. Source: Field interviews |

Third, as mentioned by DNFE volunteer teachers, communication with highland community members could be hindered by language differences and occasionally by limited acceptance by communities. In some CLCs, women participate less than men, as they feel embarrassed to show their lack of language skills in front of their children. The continuous efforts of the CLC volunteer teachers to encourage community participation would stimulate further community participation. Volunteer teachers point out the insufficiency of audiovisual equipment (such as TV and radio) which would facilitate learning and attract a larger number of learners57.

Fourth, communities do not take advantage of some of the available services. For example, some DOAE ATTCs are not fully utilized by farmers in the concerned villages58. Some farmers consider that the current functions of ATTCs do not offer any value-added services in their favour59. A suggestion was made to facilitate community participation through DOAE/community meetings and public hearings before initiating development activities. Further dialogue is needed between communities and the ATTC staff in order to explore joint decisions on services responding to the actual needs of farmers (such as market information, cash crop production training and support through the facilitated management of revolving funds) 60. They could also jointly address the problem of unsustainability of learned skills among farmers, due partly to the lack of appropriate equipment and facilities at the community level (e.g. those needed for food processing). ATTCs would potentially be appropriate platforms for these purposes.

Similar to other government agencies, DPW adopts a participatory bottom-up approach for decision making. In addition to an annual community meeting, there is a monthly meeting of extension workers at provincial offices. The outcome is communicated to the central office. In case of emergencies and issues that would need particular attention, the provincial offices can make special requests to the central level to consider eventual assistance61. This process, which appears to be put in practice in many instances, could to be encouraged.

Similar to other government agencies, DPW adopts a participatory bottom-up approach for decision making. In addition to an annual community meeting, there is a monthly meeting of extension workers at provincial offices. The outcome is communicated to the central office. In case of emergencies and issues that would need particular attention, the provincial offices can make special requests to the central level to consider eventual assistance61. This process, which appears to be put in practice in many instances, could to be encouraged.

Furthermore, it would be important for all support agencies to respect the cultural and social diversity of hill tribe communities. Many hill tribe people interviewed point out that eroding tradition has been causing problems in their communities. Genuine participation of the highland communities could only be achieved when local conditions and community needs are taken into consideration.

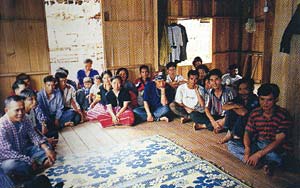

Discussion at the community

(DPW-supported village, Samoeng district, Chiang Mai)

Overall, it is hoped that the ongoing efforts by support agencies to further promote participation of and communication with highland communities will, in spite of various constraints, particularly the lack of human and financial resources, be continued.

Due to the influx of modernization influence from lowland areas, an increasing number of highland communities have become aware of the need to harmonize modern knowledge and local wisdom. Education can facilitate the process, contributing to community development and enhanced wellbeing, with the proviso that community participation and sense of ownership be promoted and sustained. In this connection, as a means to maintain the socio-cultural heritage and integrity through inter-generation communication, the importance of local curriculum development is recognized by a number of communities, as well as concerned governmental and non-governmental organizations. A local curriculum "reflects the knowledge and experience that teachers and learners can find in the community, and corresponds to the needs of the local people. The materials and course contents should therefore be developed by the community, learners and teachers"62.

Local curriculum development is implemented in a growing number of educational institutions, including highland CLCs. According to the National Guideline for Non-Formal Education, the local curriculum should constitute 20 percent of the total primary school curriculum. In the meantime, the local curriculum in most DNFE CLCs does not reach up to this minimum level. However, according to the research findings, communities located away from the educational institutions implementing local curricula are not familiar with the concept. Moreover, for tribal people struggling to secure their day-to-day food supply, a local curriculum, which is a long-term process to foster knowledge and understanding of local cultures among children, would not appeal with equal urgency. As for schoolchildren, they tend to be confused about the purpose of a local curriculum, which to them could appear as "backward" knowledge and skills.

Local curriculum development is implemented in a growing number of educational institutions, including highland CLCs. According to the National Guideline for Non-Formal Education, the local curriculum should constitute 20 percent of the total primary school curriculum. In the meantime, the local curriculum in most DNFE CLCs does not reach up to this minimum level. However, according to the research findings, communities located away from the educational institutions implementing local curricula are not familiar with the concept. Moreover, for tribal people struggling to secure their day-to-day food supply, a local curriculum, which is a long-term process to foster knowledge and understanding of local cultures among children, would not appeal with equal urgency. As for schoolchildren, they tend to be confused about the purpose of a local curriculum, which to them could appear as "backward" knowledge and skills.

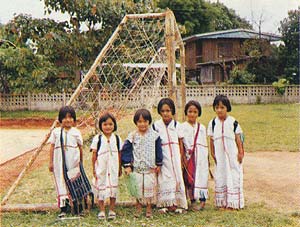

IMPECT-supported primary school

students wear traditional uniform every Friday

(Mae Wang district, Chiang Mai)

In promoting local curricula, lack of teaching material is another major issue. More adaptation of available material is necessary, as well as further coverage of subjects meeting the needs and realities of hill tribe communities. This would be an area where agencies such as DOAE and DPW could collaborate with DNFE, to identify the needs of highland communities and share their own technical expertise and experience on specific subjects. In fact, efforts are being made to further promote local curricula not only in non-formal but also in formal education curricula.

|

IMPECT first implemented local curriculum development seven years ago in Mae Wang district (Chiang Mai province) as a pilot project. Since then IMPECT has been communicating the importance of local curriculum to government agencies. The local curriculum development in Mae Lang Kam village (Hang Dong district, Chiang Mai province) started two years ago, through a participatory consultation process with the community and government representatives. Evaluation has been carried out at the closing of every semester. Currently two villages in Samoeng district (Chiang Mai province) have adopted a local curriculum, while it is under discussion in another village. Contents are on agriculture, tradition and customs as well as on livelihood. The proportion of local contents on each subject is decided in consultation with the community. The share of the local curriculum has been increasing, even in formal education. IMPECT also supports a school in Nong Tao village, covering primary levels one to six, where 67 boys and 54 girls are enrolled, with eight teachers. Out of 26 grade six students in 2000, 24 pursued further studies. School activities are supported by children's savings, and DNFE provides textbooks. Subjects taught include life skills, social science, local habits and customs, occupations (including agriculture) and Thai language. Food processing, cooperatives and marketing are among the subjects taught. The local curriculum constitutes 20-30 percent of the total curriculum. The head teacher suggested that skill training to improve product quality to meet market standards would be an important subject, contributing to enhanced quality of life for the community. The teaching skills of local people should also be promoted. According to the village chief, there has been some disagreement within the community about the idea of establishing a school, as the community does not understand its role. The community used to view the school as a source of problems (influx of new culture), not responding to real local needs. Upon implementation of the Education Law in 1999, things have developed more favourably. The village chief suggested that further collaboration between teachers (most of whom are from other villages) and communities be promoted. Source: Field interviews |

For the composition of the school curriculum, it would not be realistic to examine the ideal balance of formal (common subjects countrywide) and local curricula. Rather, the share should be determined based on the needs of the respective communities. A local curriculum would be sustainable if it is well understood and managed by teachers and community members. Awareness building on the importance of a local curriculum is essential, both for adults and children in the community. Community participation in the process should be further promoted through meetings with concerned agencies. The recruitment of community teachers should also be encouraged, for which capacity building of village leaders and strengthening of community involvement in the implementation of a local curriculum are priorities. Promotion of local curriculum development calls for accelerated efforts in such a way as to benefit a larger number of highland communities.

By cooperating with local communities, field-level workers (such as teachers, extension workers and volunteers) can play a crucial role to promote education and learning opportunities among hill tribes. They can be a "bridge" of communication between the hill tribes and governmental and non-governmental organizations. However, they face a number of constraints to fully perform their functions.

Most importantly, governmental and non-governmental agencies face an acute lack of workers, such as DNFE volunteer teachers, DOAE volunteer hill tribe farmers and DPW mobile units. Another constraint is insufficient facilities to apply and maintain skills people earn in the training. This also makes it difficult to follow up on the impact of the training carried out. Moreover, funding allocated to each worker has been in decline. For example, DOAE ATTCs have been facing a progressive drop in budget and personnel, resulting in limited coverage of services to highland villages63. For DNFE, the dearth of volunteer teachers is a major problem in implementing highland area education. With a little increase since the previous year, there are 300 highland teachers and 87 for the lowlands in 2001.

Capacity building of field workers should be promoted to enable them to more effectively respond to the needs of hill tribe communities. DNFE volunteer teachers themselves pointed out that for CLCs to be more useful to communities, volunteer teachers need to be well prepared (with knowledge on life skills, agriculture and health) before starting their assignment. Once assigned, volunteer teachers are, in addition to teaching, expected to be part of the community to tackle the community problems64. Their moral and ethics need to be elevated. However, with limited salary and few training opportunities (normally once a year), it would not be realistic to expect too much from volunteer teachers65.

DOAE volunteer hill tribe farmers used to receive 1500 baht per month until last year as compensation for their 10 days per month work at an ATTC. This year, budget prospects for volunteer farmers are unclear.66 DOAE extension workers and volunteer hill tribe farmers express the wish for further training, in order to acquire or promote skills responding to the changing needs of highland communities. For example, in the past, volunteer hill tribe farmers used to serve as translators; with an increasing number of young hill tribe people able to communicate in Thai, they now serve as agricultural leaders or extension and DOAE representatives in villages. Therefore, in addition to an annual training in Chiang Mai, they hope to obtain relevant knowledge and skills67.

DOAE volunteer hill tribe farmers used to receive 1500 baht per month until last year as compensation for their 10 days per month work at an ATTC. This year, budget prospects for volunteer farmers are unclear.66 DOAE extension workers and volunteer hill tribe farmers express the wish for further training, in order to acquire or promote skills responding to the changing needs of highland communities. For example, in the past, volunteer hill tribe farmers used to serve as translators; with an increasing number of young hill tribe people able to communicate in Thai, they now serve as agricultural leaders or extension and DOAE representatives in villages. Therefore, in addition to an annual training in Chiang Mai, they hope to obtain relevant knowledge and skills67.

DOAE Hmong tribe farmer volunteer

(Baan Huang Soi ATTC)

As for DPW, while it carries out a wide range of development and welfare activities (Annex IV), there is only a limited number of workers in the mobile units to reach remote communities. For example, it is pointed out that "the range of work (of the Tribal Research Institute under DPW) is severely restricted by the availability of qualified researchers and a modest budget"68.

As a means to address the issue of limited personnel, recruitment of hill tribe youths, who often face unemployment upon termination of their schooling, could be considered. In fact, DPW in 1999 carried out an "employment for graduates" project with the aim of solving the unemployment problem of graduates and retrenched workers. Under this project, 26.14 million baht from the Miyazawa Loan was spent on various projects, including on information system development for hill tribe welfare and development centres. DPW provided 1.83 million baht to employ (from April 1999 to May 2000) 16 new graduates, unemployed and retrenched workers to set up an information system network on the administration of welfare services and development for hill tribe people69.

A possibility could be explored to train more hill tribe youths (many of whom face employment problems) not only to be extension workers or volunteer teachers but also to participate in local decision making in government agencies. Through capacity building such as training, they could be suitable candidates to be volunteer teachers or extension workers, contributing to the development of their own communities. This would also alleviate the lack of human resources in highland development. And it would be in line with the growing willingness of hill tribe youths to be actively involved in highland development of their communities.

|

The Royal project was launched in 1969 to respond to the problem of opium production and slash-and-burn agriculture among hill tribes. From the start many agencies, national and international, public and private, collaborated with the Royal project. It was intended to be the seminal project to help fund highland agricultural research, development and experimentation work, prior to and alongside the intensive efforts of state agencies to build up their capacity in newly recognized areas of national concern. The activities were to be flexible and responsive to developing situations in order to assist various government works. The main objectives are: (1) assistance to mankind; (2) natural resource conservation; (3) eradication of opium cultivation and of the addiction problem; and (4) promotion of the proper balance in the use and conservation of land and forest resources. The main work areas include research, agricultural extension, development and socio-economic activities. Agricultural extension aims at introducing hill tribes to appropriate cash crops and research-based agricultural technology. Tribal people were given equitable allotments (of fruit, cash crops and livestock) and guidance, to learn to gain sustainable income without destroying forests. This work discouraged their migratory propensities. The Royal project currently runs 28 extension stations in Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, Mae Hong Son, Lamphun, Phayao and Nan provinces, covering 274 villages (10 695 families or 53 589 people). Source: The Royal project |

Agencies such as DOAE, DNFE and DPW at national and local levels have their own functions to fulfil in assisting hill tribes. It remains true, however, that the support activities of various government agencies are largely directed to lowland areas, though services provided to highland areas are increasing. Besides, as was pointed out by government officers interviewed for this research, inter-agency collaboration in support of hill tribe people has not been carried out in an integrated manner. For example, agricultural development in past years "lacked linkage and integrated management among the concerned agencies".70

There are in fact many examples of inter-agency collaboration, including those with NGO involvement. For example, DOAE cooperates with the Royal project, DNFE and the Royal Irrigation Department, and is collaborating with NGOs such as CARE, in terms of information sharing and providing venues. There is regular cooperation between DNFE and the Ministry of Health for training volunteer teachers. DPW has collaborated with CARE (on watershed and natural resources), the Christian Children's Fund (on children), UNICEF (on emergency relief), JICA (on cottage industry and through the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers) and DOAE (on agricultural training)71.

If carried out in a comprehensive manner, inter-departmental collaboration and central-local coordination would be effective ways to mutually complement limited budget allocation and the dearth of human resources and capacities. It would further help the concerned organizations to better perform their designated functions, reducing the gap between policy and implementation. In response to the complexity of the situation surrounding hill area development, attempts to harmonize or integrate the numerous and occasionally conflicting policies and objectives would be extremely useful. Ultimately, more effective inter-agency collaboration would enable adequate services to more properly attend to the needs of the hill tribes.

To date, DPW has been playing the role of coordinating agency concerning hill tribe-related issues, providing a wide range of services for the development and welfare of highland communities. With the other ministries expanding their support to include remote hill tribe villages, DPW has gradually been focusing geographically on communities not covered by other line agencies and thematically on social welfare issues.

The efforts by the government agencies could be supplemented by NGOs. In fact, IMPECT collaborates with DNFE on local curriculum development. It supports 100 students at high school and university levels under inter-tribal education and cultural training. In parallel, IMPECT promotes local curriculum development in nine schools; two in collaboration with DNFE, six with DNFE (out of which three to four were initiated by IMPECT and later transferred to DFE) and one on its own. IMPECT and DNFE remain in contact to cooperate in enhancing the local curriculum72.

As pointed out by DNFE volunteer teachers, integrated support throughout the process of education and training (from technical to marketing) would be preferable, in such a way as to materialize sustainable rural development in a participatory manner. Extension workers, volunteer teachers and farmers would be encouraged to jointly discuss problems facing the highland communities, including youth and employment issues,73 where governmental and non-governmental organizations could facilitate the process.

Further enhancement of inter-agency collaboration would be useful, particularly if promoted in a systematic and holistic manner. Sharing of experience including lessons learned and best practices would be very useful. The concerned agencies could share the materials they possess for villagers to use. Today, the quality of training, which is normally of short duration (average of two to three days), lacks follow-up. The concerned government agencies could join their efforts to provide more comprehensive training taking advantage of their respective technical expertise74, in such a way as to promote long-term capacity-building among hill tribe people as well as for field-level workers.

55 Thailand's Experience with Lifelong Learning via Community Agricultural Services and Technology Transfer Centres

56 Interview, Social Research Institute, 22/05/01

57 One problem is insufficient solar energy for a TV in a CLC. (Field interview, DNFE, 07/09/01)

58 Villagers visit royal projects on a regular basis to sell their products meeting quality standards required for the royal project (about 75 percent of total production). (Field interview, DOAE, 09/07/01)

59 Field interview, ATTC, 07 and 09/01

60 Field interview, DOAE, 06/09/01

61 Interview, DPW Bangkok, 31/07/01

63 A DOAE extension worker in Chiang Mai takes care of three ATTCs in two districts all by herself, depending on the intensity of ongoing activities. The budget and function of agricultural extension is declining (there is currently 300 baht/month for transportation). The last training received was three years ago; this extension worker considers it necessary to upgrade her skills to respond to farmer needs (field interview, 07/07/01).

64 In spite of communities' wish, volunteer teachers tend to go back to the lowland during the monthly leave period.

65 Field interview, DNFE, 07/09/01

66 Field interview, ATTC, 06/09/01

67 Field interview, DOAE, 06/09/01

68 Tribal Research Institute brochure

70 Thailand's Experience with Lifelong Learning via Community Agricultural Services and Technology Transfer Centres

71 Field interviews, May, July and September 2001

72 The number of students varies from one school to another, from a minimum of 70 to a maximum of 400. There are 12 to 15 teachers in each school.

73 IPM is an example. There are now two agriculture experts among the DNFE volunteer teachers in Chiang Mai. Four other volunteer teachers received IPM training conducted in central Thailand, first for three and a half months and then two and a half months. One of the four teachers explained that her CLC includes more than 100 hours of local curriculum, depending on the age of the students. IPM is a useful subject. Another teacher, though not having received specific training, consults with the DOAE district office and learns about soil problems by herself, trying to tackle them together with the community (field interviews, DNFE, 07/09/01).