Tsetsgee Ser-Od, Mongolia

Md. Mustafa Hussain, Bangladesh

Brian Dugdill, Dairy Development Specialist

Introduction

FAO recently completed two smallholder-based dairy development projects in Bangladesh and Mongolia. At first glance the countries and the projects are vastly different and could not be further apart from, for example, a population density or climate standpoint. In fact there are many similarities from a smallholder dairying perspective.

This paper compares and contrasts smallholder dairying in the two countries with a focus on two quite different, but innovative models. Both models have been developed and adapted to produce quality milk from available local resources, at a profit for smallholders and, at affordable prices for urban consumers, including lower-income families. The paper also draws on the lessons learned studies carried out by national experts under the project in the two 7countries6 and the Terminal Reports for the two FAO projects7.

Milk production

Some basic comparative facts and figures for the two countries and the farming and dairy production systems are summarized in table 1. In Bangladesh, where land is a serious constraint, smallholders stall feed their cows (and buffaloes) at home. In Mongolia, where land is plentiful, nearly all the animals milked (cows, yaks, horses, camels, goats and sheep) graze the steppe and are constantly on the move, even in winter. The key constraints to improving productively and profitability are the same, namely: (i) enhanced feeding (ii) shortage of improved stock and (iii) insufficient knowledge for raising management skills.

Table 1: Selected comparative facts and figures

Item |

Bangladesh |

Mongolia |

| 1. Basic data | ||

| Population | 140 million | 2,5 million |

Population density |

1,000 per km2 | 1.6 per km2 |

Poverty & nutrition |

48% - below MDG income poverty line ($1/day) 30% - under-nourished + 30% - real unemployment |

30% - below MDG1 income poverty line ($ 1/day) 20% - under-nourished + 30% - real unemployment? |

| Climate | Hot, humid, tropical |

Cold, semi-arid, extreme continental |

Natural disaster risk |

High: prone to regular flooding and tsunamis |

Medium: prone to periodic dzuds & droughts |

Topography & soil |

Flat, alluvial, very fertile, abundant water 3 rice crops/yr |

Undulating steppe, mountains rising above 4,000m, poor soils, frequent droughts; short 90 day growing season |

| GDP | USD 423 (2006) |

+ USD 723 (2006) Growing rapidly (mining, tourism) – 14% pa |

| Agriculture | Crop-based 21% of GDP (livestock 6% - when manure, hides & skins etc counted) Agri exports Employment : 52% |

Livestock-based 22% of GDP (livestock 81%) Agri exports : 20-30% Employment : 40% |

Farming systems |

Mainly subsistence Paddy (rice) Crop-vegetables Paddy-livestock Paddy-fish-livestock Small scale dairy |

Mainly subsistence Nomadic herding Crop (wheat/vegetables) Crop-livestock More intensive dairy (recent) |

2. Milk production |

||

Milk availability |

19 kg per capita Imports - ? per capita 50% formal market |

134 kg per capita (rural 200 kg / urban 50 kg) Imports - 20 kg per capita Imports - 50% formal (urban) processed milk market |

| Milk animal | Cattle, buffaloes (22 million) |

Total – 40.1 million Cattle, yaks, horse, camels, goats, sheep |

Smallholder families with milk animals |

15 million households |

85,000 households |

Ave. milk production (cow) |

200-300 per 180 day lactation Good milk yield for improved cattle (10-25 kg) |

5-8 kg. day Improving with AI & on specialized dairy farms |

| Services | Vet. /Breeding (AI): poor coverage - delivered mainly by Government. Where dairies have set up their own support services systems coverage good. Credit: readily available (20% pa interest). |

Vet. /Breeding: good coverage - delivered by private sector vets & AI technicians. Dairy cow genetic Credit expensive (+30% interest pa) & difficult to get |

3. Producer Organisations |

||

| Type | 2-tier dairy cooperative (150,000 families in 1,200 village coops) CLDDP women’s groups (8,000 families in ??? Village Groups) |

Dairy herder dairy groups (20-40 families) Single-tier dairy cooperative (40 families) |

4. Markets access |

||

| Market type | Huge Mainly informal Low rural & urban purchasing power. Milk producers relatively close to urban markets |

Small Rural areas informal, urban increasingly formal Rapidly increasing urban purchasing power Milk producers widely & sparely dispersed |

Dairy enterprises |

Since mid-1990s, more than 20 investors set up dairy companies, of which 75% use local milk |

12 milk processors; 2 with business models based on recombining veg. oil & SMP |

Mongolia

Because of the harsh environment and vast grasslands (only one percent of the country is settled or cropped) livestock are hugely important in what was, until very recently, a predominantly nomadic culture. Milk is sacred and milk and dairy products are staple foods and produced in great abundance from 40 million cattle, yaks, camels, horses, goats and sheep. Prior to 1990 during the socialist period, Mongolia used to be self-sufficient in milk. Under the socialist system the country had 42 collective dairy farms with improved dairy animals, state-run milk and butter collection networks, and a large state-run processing plant in Ulaanbaatar, the capital. The state system produced enough processed milk and dairy products for the entire urban population, even though 80 percent of the milk is produced in the short June-August growing period.

During the rapid transition to the market-based economy in the 1990s the dairy industry, like other food industries collapsed. By 2002 most of the processed milk sold in urban areas was imported. The industry was characterised by obsolete infrastructure and technologies, a chronic shortage of trained people and consumer concern about the quality and safety of Mongolian milk and dairy products. Like other countries in the East Asia region, Mongolia is rapidly urbanising and domestic products need to be tailored to modern market tastes. In 2002 Mongolia turned to the Government of Japan and FAO for support to revive the dairy sector. Accordingly, a project was developed: Increasing the supply of dairy products in Mongolia by reducing post-harvest losses and re-stocking with a budget of US$ 2 million, provided by the Government of Japan from its Kennedy Round II facility. The project started in October 2004 and was completed on schedule and on budget in September 2007. Following intensive stakeholder consultations a strategy was developed to re-build and modernise the dairy sector using a sector-wide, cow to consumer approach involving public and private sector partnerships. Previous attempts to revive the sector under the white revolution programme had failed, largely due to resource constraints

The Mongolia dairy food chain model

The modern dairy food chain model evolved from the lessons learned during the dairy food security project, and is inclusive of all milk producers, irrespective of type and size (nomads, peri-urban households, small dairy farms etc). The model links producers to small, medium and large scale processors through six flexible modules, one for each link in the cow-consumer dairy food chain, each capable of being adapted to the local situation and each of which must be profitable. The modules include: (i) milk producer organisations, (ii) dairy service centres, operated on a full cost recovery basis by private vets., (iii) milk collection units, (iv) milk cooling centres, (v) milk processing units and (vi) “One-Stop” milk sales centres.

While the basic model centres on liquid milk, for more remote areas the model is adapted for primary processing out on the steppe for conservation and reduced transport costs, e.g. cheese production. The market in Mongolia and the region is for processed cheese, mainly for fast food outlets. Yak cheese is produced by herder groups, matured and collected. Best quality is sold vacuum packed as natural cheese, the remainder is converted into processed cheese, which has a longer shelf-life and is easier to store and transport.

In addition to the sector-wide strategy, both models are supported by innovative marketing and capacity building features including:

The two models are now mainstreamed into the 10-year National Dairy Programme for the period 2007-2016. The target is to produce and process at least 90 percent of the milk sold in the formal market locally by 2010, up from 2.5 percent in 2003.

At 134 kg per person per year, milk availability in Mongolia is high by Asian standards; even so, with just 2.5 million people, half of who live in urban areas, the market is very small relative to the country’s potential and comparative advantage for producing ‘clean’ milk. With its huge milking herds and vast grasslands, Mongolia has a clear international comparative advantage for producing and exporting clean milk to ecologically-conscious markets; hardly any pesticides or animal drugs and no milk-stimulating hormones are used. Having substituted the vast majority of imports with domestic milk, the next step is to look to exporting quality, niche products to the rapidly growing markets of milk-deficit countries in the region to continue to grow the dairy industry. Processed cheese will be one of these products.

Initial results have been encouraging. By the end of 2007, sixteen commercial modules/units are in operation. The project shared the investment risks with its partners by contributing up-to-date knowhow and limited equipment (approx. USD 350,000). The partners invested about USD 1.3 million in equipment and buildings. The quantity of domestic milk entering the formal market in 2007 was 16 million litres, up from 2.5 million litres in 2003. This is expected to increase to 24 million litres in 2008. Under the National Dairy Programme private investors, including the two companies reconstituting imported FCMP, are expected to invest upwards of USD 10 million in the modules in 2008 and 2009.

Bangladesh

Prior to 1970 there was no organised dairying in Bangladesh. Acute scarcity of milk following independence from Pakistan in 1971 prompted the Government to plan a dairy project modelled on the world-renowned Indian Anand pattern dairy cooperative. Set up with support from FAO, UNDP and DANIDA, the Bangladesh Milk Producers’ Cooperative Union Limited (Milk Vita) today collects milk from over 150,000 smallholder milk producers through a network of 1,200 village cooperatives. Milk Vita almost collapsed in the early 1980s because it could not compete with imported subsidized milk powder, donated and commercial, mainly from the European Union. By the early 1990s the business had been turned around when Government withdrew from day-to day management and allowed Milk Vita to recruit professional managers. At the same time milk powder stocks around the world started to drop as western Governments began to withdraw subsidies to their dairy farmers and exporters. A number of private sector investors and NGOs copied parts of the Milk Vita model and by 2005, there were 20 or so dairy enterprises, including three large companies producing sweetened condensed milk from imported skimmed milk powder and vegetable oil. Milk Vita recently invested more than USD 10 million in an expansion programme, which is facing teething problems related mainly to inappropriate equipment selection.

FAO and UNDP also provided support to set up a vocational Dairy Training Centre to support the dairy expansion programme and to prepare an updated National Livestock Policy (NLP) in 2006. The National Strategy for Accelerated Poverty Reduction (NSAPR), published in October 2005, sets out ways and means for achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) of halving poverty and under-nutrition by 2015. It indicates that while the livestock sector as a whole grew 2.6 percent per annum since the 1970s, poultry and milk production grew at around 10 percent per annum, reflecting the significant support for the two sectors. Not surprisingly both the NLP and NSAPR single out smallholder dairying for early adoption and replication. While milk production by smallholders is now generally recognised in Government development strategy, the absence of a comprehensive national dairy programme is thought by dairy sector insiders to have limited growth.

The Grameen CLDDP (Community Livestock & Dairy Development Project) model

One of the NGOs to adapt parts of the Milk Vita Cooperative dairy model was the Grameen Motsho (Fish) Foundation. The Foundation is a non-profit organisation under the Grameen Bank, world renowned for its highly innovative and successful micro-credit programme for very poor people. The Foundation was set up in 1986 and by 1998 was farming over 1,000 small ponds in partnership with 3,000 poor families in the north-west of the country. It works through a grass roots Village Group-Village Centre structure, supported by service units. The profits from fish sales are shared 50:50 by the Foundation and the VGMs (Village Group Members). By the late 1990s, earnings per VGM had levelled off at around USD 70 per year. The Foundation was looking for ways and means to: (i) increase pond operator earnings, (ii) raise the productivity of its fish ponds and (iii) improve the nutritional status of VGMs and their families, while involving more direct women beneficiaries, as over 90 percent of the VGMs were men. The solution was to add livestock to the fish farming system in order: (i) to make available food for home consumption and sale (ii) to provide dung to fertilise fish ponds to improve productivity and (iii) to shift the focus to women. The Foundation turned to FAO and UNDP for support in 1998 and the project started in 1999. It was completed in 2006. The budget was USD 3.43 million, provided by the Foundation and UNDP, including USD 0.82 million for the revolving community micro-credit scheme.

The Grameen CLDDP model is profitable dairy chain model that is part of an integrated, community-owned crop-fish-livestock farming system. Over 8,000 very poor landless and assetless VGMs belong to five-person groups. Following training and build up of savings, the VGMs access small commercial loans for livestock and other income generating activities. Loans may be accessed for in-calf heifers, in-calf cows, store cattle for fattening, goats, pigs, poultry, ducks crops/fodder, milkshaws, and bio-digesters and more recently, vegetables, fishing gear, social forestry. More than seventy percent of the loans are now for dairy cows because they return the most in terms of profits, nutrition, asset accumulation and social standing. The loans include compulsory animal insurance and a feed component with feed produced by their own feed mills.

VGMs have access, at full cost, to all the inputs and services needed to produce and market milk, e.g. feed, AI, animal health, credit etc. They supply milk surplus to their household requirements to community-owned milk collection centres for primary processing at community-owned dairy enterprises. Because of its reliable quality, chilled milk is sold at a premium price to established dairies such as Milk Vita, Bikrampur Dairy and Grameen-Danone Foods for further processing and marketing. Some milk is processed and marked locally using a low-cost, locally fabricated in-pouch filling-pasteurising-cooling system. This equipment was also exported to Mongolia for used by small and medium-scale dairy enterprises.

The community-owned feed mill enterprises provide quality dairy rations, compounded from locally available agro by-products, for the VGM-owners who either have insufficient land or no land at all to grow their own feed and fodder. Once smallholders have four or five cattle, they have enough dung to take out a loan for a bio-digester to produce gas for cooking and lighting. The spent slurry from the bio-digester is then used to fertilise and increase the productivity of fish ponds. Every two or three years the ponds are emptied, the slurry dried and used as crop fertiliser. In this way smallholder dairying has become an important component of an integrated and environmentally sustainable poor peoples’ farming system.

The VGM-smallholder milk producers own 70 percent of the community feed mills and dairy enterprises (Grameen owns the other 30 percent) and thus share the profits of the enterprises. While in some ways it is a social dairying model, it is commercial in operation.

Some of the benefits for smallholders include:

Nutrition: e.g. pre-project no households consumed milk, now all 6,000 households with cows consume between 0.2 and one litre daily.

Earnings: e.g. average earnings from fish and milk increased from 19 to 125 US cents a day, enabling purchase of other essentials such as food, schooling, clothes etc.

Household accumulation of physical assets: up 145 percent and include tube wells for safe water, bio-digesters for clean cooking and lighting, sanitary latrines etc.

So far these benefits8 have resulted in the graduation of over 5,000 smallholder households out of poverty. The model is being adapted and scaled up across the country and in Nepal. The new Grameen-Danone Foods9 Bogra Dairy started up in 2007 and produces low-cost bio-yoghurts for the poor. In five very poor districts in the north-west 10,000 smallholder families will be covered under a USD 15 million programme, funded up to 2010 and managed by the NGO, Palli Karma-Sahayak Foundation.

School milk

Both countries have school milk programmes. The Bangladesh programme is quite small and operated by an International NGO. Originally the milk was imported, pre-packed in UHT cartons from Thailand. Now imported milk powder is reconstituted in a joint venture with a local dairy. The above-mentioned National Strategy for Accelerated Poverty Reduction includes a plan to promote a School Lunch Programme to improve attendance, reduce incidence of mal-nutrition as well as generating demand for local produce and catering services through backward and forward linkages. Community participation is to be a key driver.

In Mongolia the Government launched a school lunch scheme in 2006. The scheme is operated under a public-private sector partnership arrangement with food companies bidding for local school lunch contracts. Following intense lobbying by the Mongolian Food Industry Association and the dairy project the Government now insists that only domestic produce is used. 80 percent of the meals are now provided by dairy enterprises. Different dairy products are provided on alternate days and the scheme boosts cash flow and earnings for the concerned dairies and, in turn, milk producers. The school lunch/milk programme is linked to the generic Mongolia milk advertising campaign.

In addition to supplying regular nutrition, the scheme also show-cases Mongolian milk and dairy products to tomorrow’s customers. The scheme current covers about 200,000 primary school children across the country.

Dairy development programmes and scaling up the models

The two countries have different approaches to dairy development reflecting, perhaps, the relative importance of milk to the economy and nutrition. Milk is a staple food in Mongolia and so there is now a fully funded National Dairy Programme involving public-private sector partnerships for scaling up the models (see paras 10 and 11). In Bangladesh milk is just one of many foods important for human nutrition. However, the project demonstrates how dairy can be converted into an integral part of the community. This is despite that there are no specific national dairy plans or programmes and dairy development is driven largely by the private and NGO sectors (para 13).

Lessons and conclusions

Milk is nature’s most complete food. With appropriate policies, strategies and planning, smallholder dairying can improve the livelihoods and well-being of rural communities and urban consumers alike while making profits for the dairy operators at each stage of the dairy value chain. Smallholder dairying is simple in vision, but relatively complex in implementation.

If smallholder dairying works in such harsh and differing environments as Bangladesh and Mongolia, it should work in most between situations where markets demand quality milk and dairy products and smallholders produce milk competitively. In Bangladesh and Mongolia these countries success was achieved by:

In these processes, committed people and enterprises (stakeholders) are more important than geography, climate or politics.

Smallholder dairying is now recognized as one of the key tools for helping both Bangladesh and Mongolia achieve their World Food Summit (1996) and Millennium Development Goal (2000) targets of halving under-nutrition and poverty by the year 2015.

Nicholas Hooton – International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)

Acknowledgement: This paper presents an overview of findings from ILRI’s work on traditional dairy markets, work led by Dr. Steve Staal, Dr. Amos Omore and Dr. Bill Thorpe and supported by many other colleagues in ILRI’s smallholder dairy team. This work has also been carried out in close collaboration with national partners throughout Africa and Asia, and with international partners, including the Food and Agriculture Organisation.

Traditional dairy markets:

Traditional and informal dairy markets, although often ignored or unrecognised, represent a large proportion of domestic dairy trade globally, and are hugely important for resource-poor farmers, traders and consumers. Work by ILRI and its partners in Africa and Asia has led to a better understanding of the scale, characteristics and determinants of traditional dairy markets, and of their importance to the poor. The work has suggested a range of technical, regulatory and policy/institutional interventions in support of a more ‘pro-poor’ approach to dairy policy and development10.

Key features of traditional dairy markets are that they are based on ‘traditional’ local products – usually liquid (raw or soured) milk sold directly to consumers in small quantities by small traders – rather than larger-scale processing and packaging of dairy products. The distinction between ‘traditional’ and ‘informal’ markets is blurred. Markets in ‘traditional’ dairy products are often legal, with licensed traders. However many are ‘informal’ – operating outside the industry’s regulatory structures on quality and safety – predominantly because of a mis-match between the demands of these regulatory structures and the low demand for food safety by consumers of traditional products.

Traditional dairy markets are very big, with market shares approaching 98% in countries such as Pakistan and Tanzania, 86% in Kenya and 76% in India. In the case of India, this traditional market share represents almost 70 million tonnes annually, compared with the total global dairy product trade of 80 million tonnes11. Mainly in the form of ‘raw’ (unprocessed) milk, traditional dairy products reach consumers through a variety of routes involving direct sales or small-scale traders. These markets are strong not only because of the low cost to consumers (compared with formal processed products) but also because of consumer preference for traditional tastes, even amongst wealthier consumers. With price incentives for both farmers and consumers, and no evidence that ‘policing’ of informal traders significantly affects market share, this strong consumer demand ensures that traditional markets will not go away any time soon (although urbanisation is likely to reduce the traditional market role because of higher costs of mass supply).

Traditional dairy markets are also very important for employment. Work in Kenya, Bangladesh and Ghana has shown that the same volume of milk sold through traditional markets supports more than five times the number of jobs compared with the formal sector, with most of these jobs paying more than the minimum wage12.

Overall, it is clear that traditional markets provide apparently efficient market mechanisms for dairy development, especially in areas with poor infrastructure. The demand for ‘raw’ milk products means that they are unlikely to be substituted by processed products based on imported milk The small-scale marketing complements the wider small-scale dairy production systems (labour-intensive farm household model with multiple outputs) with important implications for household nutrition and for environmental sustainability (based on internal nutrient recycling).

Bridging the Gap: Integrating traditional dairy markets into formal dairy development

As described above, traditional markets are often unregulated, as the low cost is based on low demand for food safety, compared with other needs, and consumers’ own assessments of milk quality. This compares with a high relative demand for food safety and consistent quality in the formal processed sector. Quality and safety issues are clearly extremely important in dairy development, so the challenge becomes clear: how can these hugely important traditional markets be encouraged to improve safety and quality, whilst maintaining their key characteristics – meeting consumer preference for traditional products at affordable prices, and supporting poor small-scale farmers and traders? Recent work, started in East Africa, but now extending to South Asia, is now indicating a series of steps that can help successfully to bridge this gap – i.e. to encourage traditional markets to improve quality and ‘formalize’. The desirable end result would be no more ‘formal’ and ‘informal’, but just ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’.

One key issue from ILRI’s work in Africa and Asia is that despite their large numbers and economic importance, stakeholders in small-scale milk production and traditional market agents are largely invisible in policy processes, with little voice in domestic and international policy. Another basic finding from work in East Africa was that licensing per se did not currently ensure better quality milk. Not only was licensing often just an exercise in fee collection, but many measures that on the surface aimed to improve quality, could in practice have the opposite effect13.

However, a series of interventions have been piloted which aim to address technical, regulatory and policy/institutional challenges to ‘formalisation’ of traditional dairy markets.

To address some of the technical challenges, a series of systems to support training in milk handling and testing have been developed, in close association with traders themselves. FAO and ILRI together with national and regional partners have developed training guidelines, published as guides for farmers and different cadres of traders, and also for trainers, and participatory training courses, based on these guidelines have been piloted. Subsequent research in Kenya has demonstrated a clear improvement in quality of milk sold by trained compared with untrained traders. Parallel to the development of training systems, ILRI worked with local traders in Kenya to develop appropriate, affordable milk containers, which both met the requirements of the regulators, and of the traders themselves (e.g. suitable for bicycle transport, with sealable lids).

To support the use of these technical interventions in transforming traditional markets towards ‘formality’, the training approaches have been combined with a process of certification by the regulatory bodies, so that trained traders are recognised by both consumers and regulators. A Business Development Services (BDS) model has been piloted in Kenya by the Kenya Dairy Board (KDB) in collaboration with an NGO, supported by ILRI. Training service providers provide milk handling and quality training to traders, who pay a fee to the service providers for this training. Having successfully completed the training, the traders can become licensed by the KDB, paying a cess fee14 based on the milk they sell. The training service providers are themselves accredited and monitored by the KDB, and in turn report back to the KDB on their courses and trainees.

Finally, evidence on the importance of traditional dairy markets for the poor has been used by a range of stakeholder groups in Kenya to lobby for policy change in support of small-scale dairy farmers and small traders. A new Dairy Policy now explicitly recognises the role of small-scale traders, supports training and incentives for safe milk handling, and establishment of a supportive certification system. The process of this policy change was not straightforward, and relied on long-term engagement in the policy process, presenting evidence based on empirical research and pilot approaches.15

There have also been successful efforts to scale out these lessons from Kenya to the East Africa region and beyond. This has included dairy sector regulators from four countries agreeing on a series of harmonised training guidelines, and on the use of these guidelines in regulating and facilitating cross-border trade in traditional dairy products. The BDS model for linking certification with training on milk quality is also being developed in Uganda. In South Asia, the Dairy Department of the Government of Assam is now developing a strategy to certify and train local market agents, whilst in Andhra Pradesh, the Dairy Action Research project is also developing training of market agents.

The above examples show how changes in technical, institutional and policy have occurred in support of smallholder dairy farmers and traditional dairy markets. But do such changes actually have an impact on the livelihoods of resource-poor farmers and traders? A recent case study by ILRI has looked at the impact of the policy change in Kenya described above. The study concluded that there were real benefits, estimated at some $30 million nationally, with benefits spread between poor consumers and producers. These benefits were mainly due to a reduction of some 9% in margins in the traditional market, from reduced transactions costs and spoilage.16

An agenda for pro-poor dairy policy and development

The evidence from the research on traditional dairy markets presented above strongly suggests that such markets will continue to play a large role for a long time, with benefits to the resource-poor, and that development of such markets can complement the formal processing market. The lessons from these analyses, and other research, present some elements of what can be termed an ‘Agenda for Pro-Poor Dairy Policy and Development’. The aims of such an agenda would include increasing the welfare of small farmers and market agents, meeting the needs of poor consumers, and sustaining the natural resource base. Specific objectives of such a ‘pro-poor’ approach, beyond traditional dairy development approaches, would include:

Thus, incorporating such an agenda in a dairy development strategy would involve:

In terms of the relevance for a strategy for dairy development in Asia, emphasising the role of traditional markets is clearly most appropriate where such markets are strong – for example in South Asia, compared with South-East Asia. However, the general lessons are still the same – in any strategy for dairy development, it is important not to forget to target local markets, with products designed for local preference, and not to assume ‘western’ product choices.

Anthony Bennett, Dairy and Meat Officer, FAO Headquarters, Rome

Dairy institution – definition: an established dairy organization or body. In the context of this region, this varies from milk producer groups, co-operatives to dairy boards and industry associations.

The focus of FAO work in the region is on promoting and supporting sustainable dairy development for the multiple benefits which accrue to farm families, rural community empowerment and increased incomes for farm families. This includes building and improving dairy institutions through the provision of truly independent policy, strategy and technical advice and assistance. Over the last 5 years – this has included activities in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Myanmar, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, Thailand, the Philippines and Viet Nam. Over the last 50 years, this also included larger interventions such as in India under the Operation Flood programme and many more.

FAO has a unique position through our involvement in dairy development initiatives and regional analysis of trends, issues, constraints and opportunities which would favour the inclusion of small and medium scale milk producers.

Challenges identified at the national level include:

A complete value chain approach is therefore needed in order for dairy development to be effective.

Challenges at regional level include:

Current issues

Asia is the highest demand growth area for milk and dairy products worldwide. Since the international milk price has grown to an all time high in 2007, this has substantially changed the interest and investment being made in dairying in the Asia pacific region and beyond. However, with growing pressures and prices for land and fodder/feed resources, and increasing interest in biofuels etc, there is now increased competition for land resources. In addition, many more Asian countries have joined not only WTO but also other regional trade groups such as ASEAN and other Free Trade Agreements which may or mat not be of benefit to the dairy sector. One of the knock on effects of this is the growth of industry joint ventures in the region to facilitate smooth uninterrupted market access for international players.

Role of institutions

Traditionally, local dairy institutions have tended to focus on milk producers groups, associations or cooperatives at various levels. While these pose their own challenges in the stepwise and progressive development of grassroots local institutions and capacity, there are many examples of top heavy institutions which, while being highly representative, can also be excessive in terms of cost to the dairy sector. A recent development is the growth of dairy industry groups (mainly private sector), perhaps directly in collaboration with government. This focuses on facilitation and consultation in view of the shared interest in dairy development. Many variations in between these two can also be noted in the region. It is also interesting to note that India, the largest dairy producing nation in the region, is now considering the path of privatisation of milk co-operatives as companies, while possibly maintaining a social function.

Experiences with institutions

NDDB India, was born of Operation Flood. Essentially milk powder and butter oil was donated free of charge, recombined and sold on the local market with returns being invested in national dairy development. Since modest beginnings in the early 1970s, India is now the largest liquid milk producer in the world (cow and buffalo milk) with almost 100 million MT produced in 2007. The success of this huge monetization programme was due to targeted and effective investment, management and organization.

There is also a huge diversity in terms of volume and experience in the region, e.g., in the Philippines, the National Dairy Authority, has a fledgling but steadily growing dairy sector. Other examples include Pakistan, which has a Livestock and Dairy Development Board (MoA) and also Dairy Pakistan which takes up a new role in the private sector. Mongolia recently had a national dairy sector revitalization programme and a new dairy act in 2006; this was made possible through high government priority being accorded to dairy development, investments and promoting public-private partnerships.

In China, dairy development is reported to be private led, with large government and donor support to reduce dependence on expensive milk and dairy product imports. In recent years, there have been extensive cow imports. There have been mixed experiences with varied production, collection and processing systems, significant problems reported in milk quality, milk price and farmers returns on milk production.

Key lessons learned include:

Resources needed

One approach which FAO promotes is the stepwise Market-Oriented Dairy Enterprise (MODE) approach. Three basic steps can be considered for milk producer groups:

Conclusions

Strategic planning for dairy development

To be successful the three below factors can be used as a guide for improving smallholder market access.

IFCN Dairy Research Center

Dr. Torsten Hemme

Introduction

The aim of this paper is review some of the factors critical smallholder enterprise-level performance and draw some generalizations about the relative opportunities for scaling up in selected countries. This analysis will take into consideration changing global dairy trends and the overall competitiveness of milk production within the context of changing structure of dairy farming..

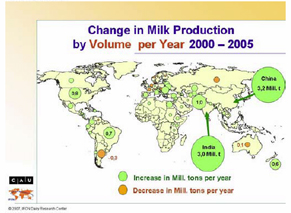

Milk production trends

Over the 2000 – 2005 period, world milk production has grown by nearly 2 percent per year and most of the growth has been in developing countries, particularly Asia, which has witnessed growth rates double global averages. However, in many cases regional trends regions trends differ significantly from country specific sector developments. For example, the highest annual growth rate in the world was observed in China, which, supported by strong gains in Inner Mongolia, grew 17% over the period. These high growth rates are driven by three factors: a) low milk yield at the start period (1,800 kg/cow/year) and rapid increase towards 5,000 kg/cow, b) very low culling rate (10-15%) and c) import of dairy cattle into the region. Growth was underpinned by consumption and prices trends as well as domestic policies which influence investment in the sector.

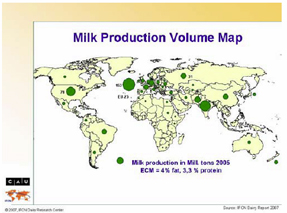

Over the same period, world milk production (cows + buffalos) rose, on average, by 11.3 million tons ECM (Energy Corrected Milk) each year (Source: IFCN). India and China, the suppliers of one-fifth of global production, accounted for approximately 3 million tons of these gains. The US, Pakistan, Brazil and New Zealand contributed an additional 0.6-1 million tons each with additional supplies originating from Eastern Europe, Middle East, North-Eastern part of Africa and a number of Latin America countries. From a regional perspective, Europe and South Asia (see Figure 1) are the most important dairy regions in the world, representing 46% of world milk production.

Production declines were observed in Argentina, Russia and Australia. This was mainly influenced by policy developments, climate and an overall restructuring of the industry. The decrease identified for selected EU countries like in France, Netherlands, Sweden, Ireland can be explained by a) technical quota adjustments due to changing fat contents, b) less undelivered milk (less on-farm use) or c) milk quota not filled.

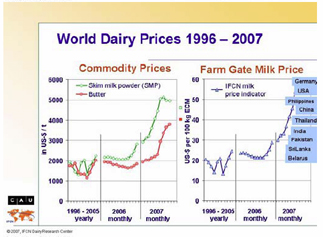

World market prices for dairy products (figure 4)

The world market price for butter and skim milk powder between 1996 - 2006 ranged between 1,000 and 2,000 US-$ per t. In the year 2007, both prices increased significantly to reach in mid-year 5000 US-$ per ton skim milk powder and 4000 US-$ per ton butter. However, these prices have eased considerably in early 2008, driven by two factors like an increasing milk supply and a reaction of consumers on raising prices for dairy products.

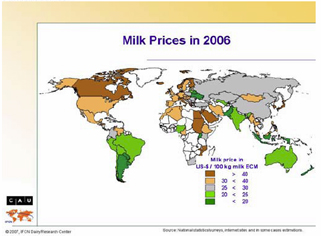

Farm gate milk prices in 200 (figure 3)

Farm gate milk prices per country range from 15 to 74 US-$/100 kg ECM (Energy corrected milk 4% fat, 3,3% protein) and can be grouped into five price level categories:

< 20 US-$: New Zealand, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Uganda, Belarus, Ukraine, Pakistan and Indonesia.

20 - 25 US-$: Australia, Uzbekistan, Nigeria, Brazil, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, India and Lithuania.

25 - 30 US-$: China, Viet Nam, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, South Africa, Colombia, Ecuador and a number of Central American countries.

30 - 40 US-$: USA, Mexico, Venezuela, most EU countries, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Slovenia, Slovakia, Israel, Iran, Mongolia, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Ethiopia, Cameroon, Thailand Myanmar, Malaysia and The Philippines.

-> 40 US-$: Canada, Iceland, Norway, Finland, Switzerland, Italy, Greece, Egypt, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Mozambique, Taiwan, South-Korea and Japan.

In 2007, domestic milk price movements in different countries didn’t respond the same way to global price movements. In Germany and the USA domestic prices responded quickly with farmers get the high world market prices. However in countries like Belarus or Sri Lanka no reaction to prices were observed.

| Figure 1 |  |

| Figure 2 |  |

| Figure 3 |  |

| Figure 4 |  |

Dairy farm structure

IFCN estimate of dairy farms numbers

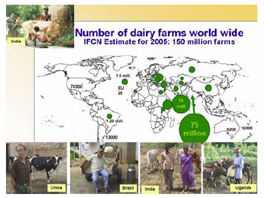

The IFCN collects data on dairy farm numbers from 73 countries with an aggregated estimate of 115 million dairy farms. (Figure 5). Based on this data and expert knowledge on dairy farm size, the total number of dairy farms in the world is estimated at 149 million. Assuming the size of the dairy farm household to be 6 people, this implies about 895 million people are living on dairy farms or approximately 14% of the world population. This implies that every 7th person in the world is living on a dairy farm.

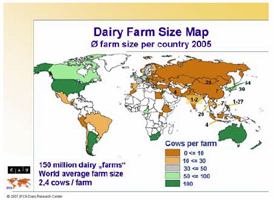

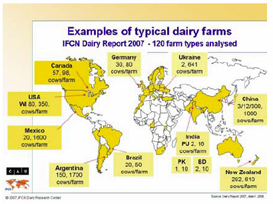

Dairy farm size

Based on IFCN estimates, average dairy farms maintain 2.4 cows/farm. In most countries, the farm size is below 10 cows (figure 6). This is especially the case for most countries in Asia, Eastern Europe, Africa and parts of Latin America. Only 15 countries have an average farm size of more than 50 cows. The six countries with a farm size of more than 100 cows per farm are: USA, Argentina, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and the Czech Republic. The average farm size in the EU-15 countries is 35 cows per farm.

Dairy farm numbers

Dairy farm numbers are highest in India and Pakistan, followed by Ethiopia, Ukraine, Turkey, China, Russia, Uzbekistan, Brazil, Iran and Romania. These countries, on average, have 1 - 2.5 million dairy farms each. By comparison, the aggregate farm numbers in the USA and the EU-15, with 78,300 and 533, 851 farms respectively, look quite small. YEAR???

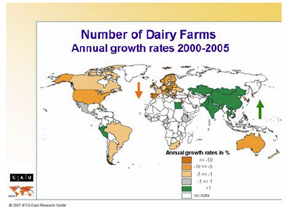

Dairy farm evolution indicates two distinct trends (Figure 7). In developed countries like the USA, Brazil, Argentina, Europe, South Africa, Japan, New Zealand and Australia dairy farm numbers are declining 210 % per year. Most developing countries show a diverse picture of increasing farm numbers with a speed of 0.5-10% per year (Source: IFCN Dairy Report 2007).

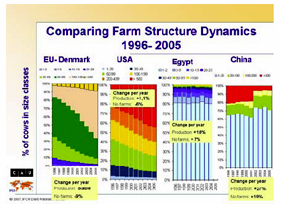

Dairy farm structure (Figure 8)

Similar to trends in dairy farm numbers, two basic trends are evident in farm structure. In developed countries, smaller farm are loosing market share at the expense of larger operations. In developing countries, however, small scale dairy farms dominate milk production and are maintaining or in some cases expanding their market share.

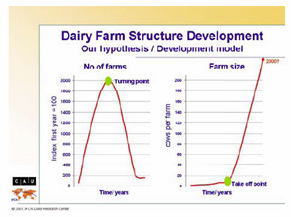

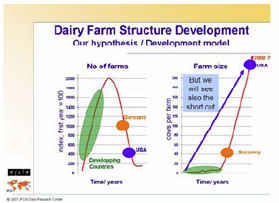

Farm structure hypothesis (Figure 9 – 10)

Based on an analysis of farm numbers and changing farm structure IFCN has developed a hypothesis for a dairy development model with two key points. There is a turning point when the number of dairy farms reaches its maximum. Until this point, increasing milk production is a result of increasing number of small farms (Example: India, Egypt, etc.) There is a take-off point in dairy development, where scaling up occurs. This point indicates structural change in the dairy sector. Countries like the USA or Germany have passed this point. It should be mentioned that this pattern will not necessarily be followed in all countries as investments in large scale milk production operations can be put in place, thus providing a country’s milk requirements. An example of this are large scale dairy farms in China.

Key conclusions Small scale dairy farms in Asia have a great opportunity to provide the milk which is needed in the region. The biggest threat is adjusting dairy farming system in recognition that scaling-up is required once land/wage rates rise.. The threat of non-adjustment is that milk requirements will be provided large scale dairy units or will come via imports from other countries.

| Figure 5 | Figure 6 |

|  |

| Figure 7 | Figure 8 |

|  |

| Figure 9 | Figure 10 |

|  |

Source: IFCN Dairy Report 2007 | |

Dairy Farm Economics

Introduction and concept of typical farms

The IFCN methodology defines two farm types for each country or region analysed17. The first farm represents an average sized farm while the second farm representing a larger farm type existing in the country. Due to the varying characteristics of dairy farms, this only explains “one” part of the milk production in the country. The aim of this section is to review the economics of dairy farming and draw out general lessons/implications for the profitability for smallholder dairy farms.

Cost and returns

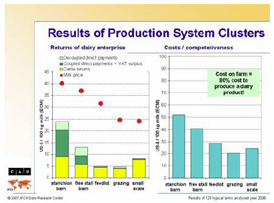

The cost of production of the 120 typical farms analysed in 2006 ranged between 79 US-$/100 kg milk in Switzerland and 9 US-$/100 kg milk in Argentina. Characteristics of these farms ranges from 80-350 cows/farm in the USA to 150-1,700 cows in Argentina (figure 11). A review of the different production systems(figure 12) reveals that the costs of grazing and small scale systems are the lowest at around 20 – 25 US-$ per 100 kg milk (ECM). They are followed by the feedlot (30 US-$) and the free stall barn systems (40 US-$). Highest costs are found in the stanchion barn system (52 US-$).

An analysis of the returns of the dairy enterprise reveals that grazing and small scale farming systems, the average milk price was around 24.5 US-$ per 100 kg, which was approximately the world market price level in 2006. Significantly higher milk prices are received (32 to 40 US-$) in the other farming systems which are mainly located in developed and protected dairy countries. Cattle returns in grazing, feedlot and free stall barn farms are similar (4 to 6 US-$), and higher in the small scale farms and the stanchion barn system which receives 7 - 9 US-$ per 100 kg.

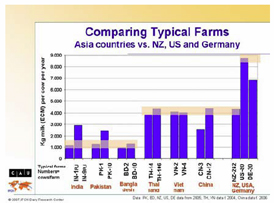

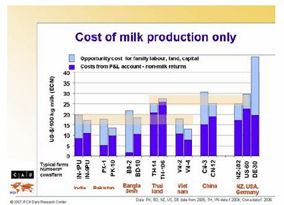

Farm economic analysis for 6 Asian and 3 developed countries

Charts 13-16 present the results of IFCN studies undertaken for the years 2004, 2005 and 2006. Milk yields in the countries India, Pakistan and Bangladesh (1000 kg/cow) are much lower than in Thailand, Viet Nam and China (4000 kg per cow) . Moreover, in most countries larger farms tend to have higher yields than the average sized farms (figure 14). However, the farms in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Viet Nam have costs of 13 – 20 US-$ per 100 kg milk which is about 5 US-$ less that the costs in New Zealand while the production costs in Thailand and China are comparable with New Zealand (Figure 14). Compared to production costs in Germany and the USA, dairy farms in developing countries have a clear cost advantage.

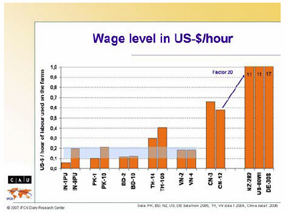

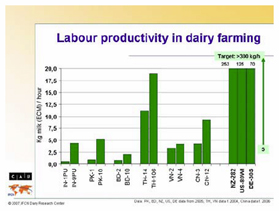

Understanding the cost differences:

The key factors explaining cost differences are feed costs, the wage level and labour productivity. In general, lower milk yielding systems have lower feed costs than higher yielding systems with 7 000 kg/cow or more. The second explanatory variable are wage levels which are lower in developing countries (figure 15) That said, developing country dairy systems often have very low labour productivity, in some cases using 1 hour input to produce one kg milk. The key challenge for small scale farming systems will be to further develop their farming systems once salaries start to rise. Development in this sense will mean improving farm management, optimising production systems and scaling up.

Key conclusions Small scale dairy farms are low cost milk producers which was one key factor faciliating gains in market share in the past. In the future these farms will face strong competition from rising wage rates. To stay in business there will be an urgent need to improve the farming systems and especially their productivity.

| Figure 11 | Figure 12 |

|  |

| Figure 13 | Figure 14 |

|  |

| Figure 15 | Figure 16 |

|  |

Documentation of farming system clusters

Farming systems: Stanchion barn (17 farms): Farms with stanchion barn. Free stall barn (42 farms): Farms with free stall barns. Feedlot (12 farms): Farms operating mainly on purchased feed with no or little owned land. Grazing (23 farms): Farms in Ireland and in the Southern Hemisphere, which are based on grazing (with a small supplement feeding of concentrates), and larger farms in Africa. Small scale (26 farms): All farms with 10 cows or less, and MA12, PE-15, and all farms from India.

Variables used in IFCN Method

Milk yield: Milk yield per cow and year (Energy-corrected milk (ECM) 4% fat, 3.3% protein).

Cost of milk production only: Costs from Profit & Loss account minus non-milk returns + opportunity costs + quota costs. ECM: Energy corrected milk (4 % fat, 3.3 % protein).

Non-milk returns: Cattle returns (calves, heifers, cull cow receipts, excluding VAT) and coupled direct payments (including VAT surplus).

Opportunity costs: Costs for using own production factors within the enterprise (own land, family labour, own capital).

Milk price: Average milk prices (excluding VAT) adjusted to energy corrected milk (ECM 4% fat, 3.3% protein).

Summing up and conclusions

The previous sections illustrated the opportunities held by smallholder milk producers; in particular, their key strengths in low production costs and ability to capture market share. In the future, small scale dairy farmers are in a good position to hold or even to expand their market share. The key challenge will be to cope with rising wage rates, the economies of scale resulting from scaling up and higher demand for food safety and traceability along the dairy chain. The key challenge is for small scale dairy farmers to adjust their farms in terms of farming system and farm size fast enough to compete with large scale dairy farm investments.

Observations on dairy development

The IFCN has developed a concept which might be able to guide dairy development focussing how to support the changes in farming systems and farm structure. Targeting the dairy farm economics means to target about 70-80% of the production cost of a dairy product.

1. There is a need to measure economic sustainability of dairy farms

Understanding the dairy farm economics is the starting point. A sustainable dairy farm insures sufficient income for the farming family, milk for the processor at a competitive price and the ability of the farmer to compete locally for resources like labour, land and also feed. Knowing these economics and how they change over time allows a classification on how sustainable the smallholder dairy farming systems are.

2. There is a need to benchmark dairy development ideas

In every dairy region, there exist of a large number of dairy development programs and numerous and diverse interventions. In almost any case we have found a solid analysis estimating the on-farm value of the programs. A benchmarking of dairy development program like the IFCN has done it in India Andra Pradesh for a 3 cow dairy farm can help a lot in defining programs or ideas which really have a high positive impact and those which have no impact.

3. There is a need to define a dairy development ladder

Once a benchmarking of dairy development ideas has been done, a dairy development ladder can be defined. Such a ladder will identify a) the best farming system for the region in terms of breed, yield, feeding, etc and b) what steps in up-scaling are most appropriate. The second point will be especially very important since local markets are changing quickly as well as the requirements to access these markets

Raf Somers, Chief Technical Advisor

Viet Nam Belgium Dairy Project

Introduction

The aim of the BTC18 project “Development and extension of dairy farming activities around Hanoi, second phase”19 is to increase the income of dairy farmers in Viet Nam. When the project started in 2005, the situation of dairy production in Viet Nam was not optimistic. The production levels were disappointing, the quality of milk was poor and the milk price was low. In contrast, the total number of dairy cattle and the total production had increased at an amazing rate of about 20% yearly, since the start of the National Dairy Development Plan (2001-2010). Due to the strong support of various national and international initiatives, the demand for cattle stayed high and so did the price of cattle. Many farmers raised dairy cattle with the purpose of selling the off spring at a high price, rather than making considerable profit with the milk production itself. Most farmers did not focus on increasing the milk production by improving the farming techniques.

The project chose to put its focus on the improvement of the quality of farming (dairy farming techniques) as well as on the quality of the milk. Most importantly, it has set up a brand new quality control and payment system, which ensures that each farmer is rewarded for the quality of the milk. Furthermore, farmers and technicians get professional advice on how to improve the quality. It’s obvious that these improvements on farm level also have a positive effect on the productivity.

This paper and the accompanying PowerPoint presentation (annex 1) are prepared for the Asia-Pacific Regional Smallholder Dairy Strategy Workshop held in Chiang Mai, Thailand from 25 to 29 February 2008. Two innovative initiatives to improve the dairy development in Viet Nam are discussed: The set up of an incentive milk payment system for smallholders and the creation of a professional multi-stakeholder dairy organization.

Incentive milk payment system

Quality of production

In Viet Nam, farmers do not raise cows to produce milk for home consumption. The only aim of producing milk is to generate income. Therefore, the project encourages professional dairy farming. It is our belief that dairy farming should be considered as a business and only if you give your cows what they need (appropriate housing, feeding & management), the economics of dairy farming are positive. Poor quality farming not only reduces milk yields but also causes poor health, prolonged calving intervals and infertility, which will most likely lead to economical losses!

Quality of milk

Milk quality can only improve if the quality is tested at farm level and if a higher quality is rewarded with a premium price. Therefore, the goal of our system is to pay each farmer an individual milk price, based on the quality of the milk (Slide 13).

….Before the intervention:

In Viet Nam, the collection of the milk goes through milk collection points. The milk of the farmers is gathered in a cooling tank at the milk collection point, before it is transported to the processing plants. In the milk factory, the quality of the milk is tested on irregular basis. If the milk doesn’t meet the factory’s quality standards, the whole bulk tank is fined. This means that all farmers are punished, even if the majority of the farmers delivered milk of an acceptable quality. Even though the milk collectors play an important role in the storage of the milk, their contribution to reduced milk quality was never questioned. Furthermore, in the old system the milk collectors had too much power, since they were in control of the payment to the farmers. Farmers complained that payments were based on suspicions and personal connections rather than on facts. Two additional problems were that plastic containers were common and that milk was often passed from one collector to another before reaching the factory. In conclusion, the old system was complicated, unfair and not transparent, which resulted in poor quality milk.

A Win – Win spirit

The intervention is based on the belief that a monopolized, unfair and unreliable milk payment system heavily undermines sustainable dairy development! The challenge was to transform this negative environment into a Win – Win situation. Three key aspects of the new system are the collaboration with the processing companies, the installation of testing equipment and the involvement of an independent laboratory.

The new quality control system

To fill in the lack of data at farmers level, ten sets of testing equipment were installed in milk collection points. The equipment, consisting of a smart card reader, an electronic scale, a milk analyzer and a microprocessor, are user friendly, accurate, fast and reliable. They have been designed to meet the requirements of the field. The fat- and dry matter content as well as the possible presence of added water in the milk is tested for each farmer. The results of the analyses are directly visible for the farmers and they receive a print out. All of this increases the transparency and fairness of the system. In addition to these basic analyses, extra milk samples are taken regularly for further analysis in an independent laboratory. There, the bacterial count, antibiotic residue and somatic cell count is determined.

Payment to farmers and collectors

The payment system was optimized and renewed. The project works together with the processing industry to pay the farmers according to the individual quality of their milk. Now every farmer gets the milk price he deserves. A specialized software is used to calculate the payment for each farmer. Electronic smart cards are used to identify the farmers in the collection points and to transfer field data to the central computer. Farmers receive their payment directly in their individual bank accounts. This has the extra advantage that the threshold to the bank is reduced, and that the bank gets information about the creditability of these farmers. Milk collectors are no longer involved in the payment of the farmers. They are only paid a commission and can receive penalty id the quality of the milk is reduced due to their fault.

Customized advice for each farmer

An important aspect of the payment system includes a bonus for farmers who apply good dairy farming practices. Farmers are evaluated every two months by a team of experts. Besides the evaluation, the experts also give advice on how to improve the farm. Furthermore, farmers have opportunities to follow practical training courses on all the different aspects of the “Good Dairy Farming Practices”. Therefore, the evaluation actually links the different project activities, such as training for farmers, introducing new technologies (for high quality forage production, avoiding heat stress, and drink water supply) and the improvement of the animal health services, back to the milk payment.

Impact and sustainability

The new milk payment system is highly appreciated and receives the support of all the parties involved. Since the quality control started a few months ago, the quality of the milk has already improved significantly. However, a problem is that not all processing companies care about the quality and offer a too high price for poor quality milk delivered to collection point outside our system. Therefore, some farmers and collectors prefer not to join our system yet.

Currently the project act as a service provider to the farmers and the processors. The project is preparing to hand over the management of the system to a new service providing company, of which dairy farmers will be the only shareholders. This new company should employ full time staff for daily management, maintenance and accountancy. The operational cost could easily be recovered from a small fee on the milk price.

Repeatability

Our intervention should be considered as example which could be followed by farmer organizations, processing companies or other projects. However, the equipment itself is only a tool. The intention to reward quality on individual basis is the most important issue.

Finally, one of our objectives is to use our system to sensitize the Government and the processing industry about the need for a transparent quality control system and the need for national regulations.

Dairy Viet Nam: a professional multi-stakeholder organization

Mission statement

The public and private dairy sector in Viet Nam recognized the need for national coordination and multi-stakeholder information sharing. Therefore, in early 2007, a group of representatives of dairy stakeholders agreed to work together and formed the Founding Steering Committee of a new organization, called Dairy Viet Nam. The mission of Dairy Viet Nam is to exchange information related to the dairy sector in Viet Nam, in order to promote sustainable dairy development. The three main channels of communication are a daily updated website, a weekly e – newsletter, and a quarterly printed newsletter. Furthermore, Dairy Viet Nam creates real opportunities for collaboration and it increases the national and international visibility of the Viet Namese dairy sector.

Success story

In one year time, the organization has developed into a highly professional organization with several committed full time staff. Four months after being launched, the hit counter on the Viet Namese website20 has reached 160.000, in average more than 1300 hits per day! The English website21 has reached 45.000 hits. Also, Dairy Viet Nam is applauded by the private and public sector. So, what made Dairy Viet Nam a success story? Probably, all started with the positive attitude of the organization! This is clearly reflected in the logo. The logo is composed of three milk drops, representing the different stakeholders. Together they form a dynamic and strong structure! The logo is also tri-dimensional and in a powerful orange color. Indeed, Dairy Viet Nam is multi-dimensional and strong organization that builds on mutual respect and understanding for each other. The slogan of Dairy Viet Nam is: Discover, Understand, Innovate! The features of our website and newsletter are discussed on Slide 65 and 66.

For the funding of the organization, Dairy Viet Nam needs sponsors. However, we are not just looking for companies to advertise but we are looking for partners! A very efficient way of a partnership is by acting as an event organizer. Our staff already proved to be professional and always aims for the best quality.

Impact

We believe that Dairy Viet Nam truly contributes to the dairy development by making interesting information available for specified target groups and the improved communication between private and public actors results in positive actions. Dairy Viet Nam is an excellent tool to link the Viet Namese dairy sector and its development with the rest of the world!

6 Lessons Learned Study. Bangladesh: smallholder milk producers, nutrition, incomes and jobs. S.A.M. Anwarul Haque, former General Manager, Bangladesh Milk Producers’ Cooperative Limited (Mil Vita) Lessons Learned Study. Mongolia: small milk producers – the key to dairy industry revival. Tsetsgee Ser-Od, Director, National Dairy Programme (October 2007)

7 Terminal Report. Grameen Bank/UNDP/FAO Community Livestock and Dairy Development Project (BGD/98/009), Bangladesh (September 2007) Terminal Report. Mongolia/Japan/FAO project: Increasing the supply of dairy products to urban centres in Mongolia by reducing post-harvest losses and restocking (GCSP/MON/001/JPN), (August 2007).

8 Data from baseline survey (1999) and monthly monitoring and evaluation reports (2000-2007)

9 Grameen-Danone Foods Limited was set up in 2006 and is in a joint social venture between the Grameen Bank and Danone, a large French multi-national dairy corporation known for its functional bio-yoghurts. Danone recently established a division named Danone.Communities and gained approval from its shareholders to set up a Euro 50 million (USD 70 million) mutual fund to channel investment into not-for-profit social ventures in developing countries. Ninety percent of the fund is to be invested in low risk securities, the remaining ten percent in higher risk social ventures. The first social venture is Grameen-Danone Foods, which produces low-cost, fortified yoghurt for sale in rural communities. A pilot dairy enterprise has been set up in Bogra. The longer-term plan is to set up a further ten rural enterprises in other disadvantaged areas of Bangladesh. The Bogra enterprise started up in February this year and currently purchases about 300 to 400 litres of milk daily from the Grameen/CLDDP Community Dairy enterprise at Nimgatchi, about 50 km away.

10 This paper draws on a range of work by ILRI and its partners, which are best summarised in a joint report with FAO’s Pro-Poor Livestoock Policy Initiative “Dairy Development for the Resource-Poor – A Comparison of Dairy Policies in South Asia and East Africa” downloadable from: http://www.fao.org/ag/AGAinfo/programmes/en/pplpi/docarc/abst44.htm

11 Based on 2004 figures from FAOSTATS.

12 See Omore, A., Cheng’ole Mulindo, J., Fakhrul Islam, S.M., Nurah, G., Khan, M.I., Staal, S.J., and Dugdill,

B.T. 2001. ‘Employment Generation through Small-Scale Dairy Marketing and Processing: Experiences from Kenya, Bangladesh and Ghana.’ Joint study, ILRI Market-Oriented Smallholder Dairy Project and FAO Animal Production and Health Division.

13 For example, the practice of confiscating milk-carrying containers from unlicensed traders would discourage such traders from using the more expensive but better quality metal containers.

14 This cess is a monthly tax on milk sold; all licensed traders and processors pay a small amount of money (approx 0.2KSh) to the Kenya Dairy Board for every litre of milk sold. This income is intended to be used to fund dairy development activities.

15 See Leksmono et al., (2006) Informal Traders Lock Horns with the Formal Milk Industry: The role of researchers in pro-poor policy shift in Kenya. ODI/ILRI Working Paper 266, ODI, London.

16 Source: Economic impact analysis of welfare benefits accruing to poor dairy farmers, traders and consumers in Kenya. ILRI, 2008.

17 _______________

18 Belgian Technical Cooperation. This is the Belgian Development Cooperation Agency that executes the bilateral project funded by the Belgian Government.

19 The project is implemented by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Viet Nam, with technical assistance of the Belgian Technical Cooperation. It is funded by the Belgian and Viet Namese Government.