Nancy Morgan

Livestock Policy Officer

FAO Regional Office, Bangkok

The primary drivers in dairy sector development include changes in demand, advances in production, transportation and communication technology, enhanced on-farm productivity due to improved management, and the expanding scope of dairy product marketing. However, a creative mix of sector policies and programmes that provide an enabling environment for sector development and private sector engagement can favourably influence the rate and shape of growth.

The financial resources commonly deployed by developed countries to support their heavily subsidized dairy industries are not available in developing countries. This absence of significant resources highlights the necessity for forging an enabling environment that is supportive of sector development through carefully crafted and focused policy interventions. These interventions should ensure engagement of the private sector through innovative partnerships, cost-sharing arrangements and meaningful participation of smallholders. In Asia, where the majority of milk is sourced from smallholders with two to five cows, this requires a deliberate and creative development vehicle generated and endorsed through a carefully organized planning process.

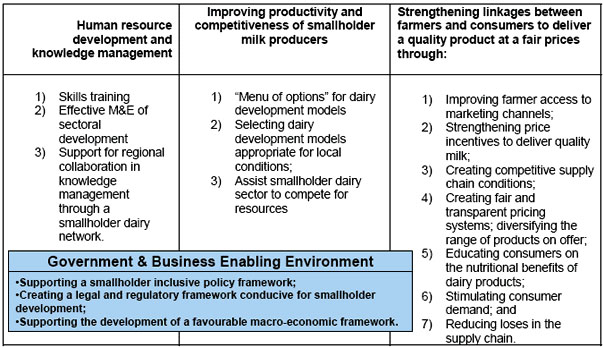

This chapter reviews the general guidelines suggested for dairy development planning during an FAO-organized technical meeting in 2008.58 It includes discussion on possible policy objectives identified during that same meeting and a review of tools and implementing mechanisms that can provide a road map for action. Table 1 outlines the pillars of support for dairy development documented in FAO’s Strategy and Investment Plan for Smallholder Dairy Development in Asia;59 these include the technical interventions that should enhance capacity and knowledge, productivity and competitiveness, and market access.

Table 1: The pillars supporting dairy development

But the identification of specific supportive activities shaping the broader context for intervention should be preceded by a development process that identifies the vision, goals, policy objectives and means of achieving these objectives. While commodity development can occur in a policy vacuum, driven primarily by economic, social and cultural factors, the broader development issues related to balanced growth, in particular smallholder inclusion in the process, and poverty alleviation through dairy development necessitates a very strategic planning process.

Many countries around the region have designed dairy development plans and strategies with many including a dairy focus within a broader livestock sector plan, such as Bangladesh (2007), Nepal (2007), Pakistan (2007) and Sri Lanka (2007). Some had designed dairy-specific plans, including the Philippines (2008) and Assam, India (2008). While some are operational, others, despite good intentions, are not being implemented because of a lack of strategic planning in the development process and a lack of consistent focus on implementation requirements, such as financing.

To provide better policy guidance to governments and dairy stakeholders in the region, participants at the 2008 technical meeting identified the following good practices in sector planning:

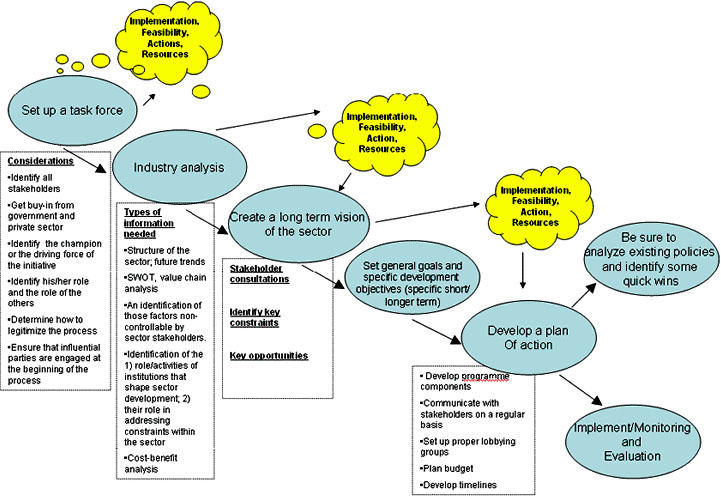

Participants in the 2008 technical meeting also devised a generic approach for sector planning (Figure 1). They agreed that broad stakeholder participation, including input from smallholders, was needed to identify a sector vision and goals that are credible and achievable and generate support among the private sector.

Figure 1: A generic approach for dairy development planning

A key priority in the strategic planning process is to identify and revisit the opportunities and constraints to implementation. The effectiveness of the plan needs to be linked to a clear recognition of resource availabilities/constraints (both human and financial), to demonstrated stakeholder commitment, particularly on the policy level and by private sector, and to an action plan accompanied by a specific time frame. Under the dynamic efforts of a respected champion60, it needs to be integrated into broader planning initiatives of the government.

|

Box 1: Factors critical to strategy implementation

The dos:

The don’ts:

What can go wrong:

The need for effective monitoring and evaluation:

|

Participants along the dairy chain often have conflicting interests and objectives. Consequently, the planning process needs to be supported by considerable knowledge about stakeholder concerns as well as a broad understanding of available tools and their ability to achieve policy objectives.

An assessment of stakeholder priorities generates a series of policy objectives. These are specific statements detailing the desired accomplishments or outcomes of a development plan. Whereas the goal of a dairy development plan might be to “contribute to national economic development by commercially, qualitatively and competitively developing the dairy sector for employment generation and poverty reduction with the participation of government, cooperatives and private sector” (Nepal, 2007), the development objectives would be more specific.

Specific examples of development objectives for the dairy sector could include: i) a reduction of imports; ii) increasing on-farm productivity and ensuring food safety; iii) enhancing nutritional status of children through milk consumption; iv) raising on-farm incomes; v) reducing post-harvest losses; and vi) ensuring fair prices for quality milk products. The effectiveness of plans that incorporate these types of objectives, assuming the availability of well-designed baseline studies, can be measured. This contrasts to more vaguely worded goal statements, such as enhanced food security, sustainable development, poverty alleviation, etc.

The key distinction: the goal is a statement of intent and an objective describes an achievable and quantifiable target or deliverable. Good objectives should:

When assessing the objectives to be achieved through a dairy plan, the menu of options for implementation or the policy tools/measures need to be considered. In most developed countries, the policy objectives of very complex programmes and plans are quite simple: to support milk producer prices and/or incomes. The mechanisms for achieving these objectives, however, can be extremely diverse, with the selection of policy measures having i) differential impacts on the many stakeholders along a chain; and ii) cost implications, particularly as consumers and the government typically finance these interventions.

Developed countries have a long history of supporting local dairy industries through policy tools that include regulated or administered prices, high tariffs or production controls/quotas, such as those in the EU and Canada that limit production increases. All of these policy interventions are designed to ensure objectives of stable and high producer incomes. The significant support for this sector, relative to other sectors, may be related to the characteristics of the product, such as the perishability of milk and dairy products, seasonable production patterns and need for further processing. In addition, dairy farms in developed countries (and in some developing countries) tend to be less diversified and more dependent on farm income than other farm operations (Economic Research Service, 2004).

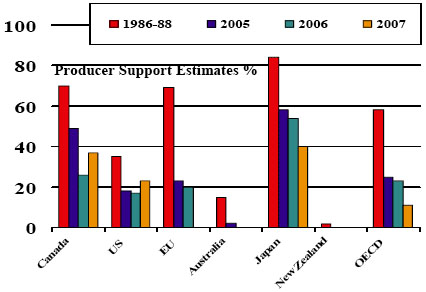

Figure 2: The dairy sector in OECD countries is heavily supported

The larger degree of support can be best assessed through measurements of sector inputs, as calculated by the OECD61 (Figure 2). These producer-support estimates (PSEs) reflect the total value of production from government interventions, such as the use of price supports, trade measures (Tariffs/export subsidies) and more generalized government input, such as direct payments. The total value of support afforded dairy sectors in OECD countries two decades ago totalled almost 40 billion euros, approximately 20 percent of the total agricultural support of 217 billion euros. At that time, the PSE, estimated at 58 percent, exceeded all other commodities except rice (80 percent).

Since then, support has declined, mainly in the EU, which accounted for transfers of almost 20 billion euros to their sector in 1986. OECD estimates for 2006 and 2007 indicated that support dropped to 18 billion euros in 2006 and to only 10 billion euros by 2007. High prices in global markets led to policy changes in the EU, which reduced government support to the sector, particularly with the use of interventions stocks and export subsidies as a means to stabilize prices. As global prices in 2008 move down, this trend of not supporting the sector may reverse itself.

In the EU, government stock-holding linked to dairy export subsidies allows for an assurance of relatively stable prices. However, as the structure of the dairy sector evolves, as milk markets become national in scope (driven by advances in transportation and processing technologies) and as dairy farms become more specialized, the impact and cost of policy tools need to be evaluated against their original objectives.

The case of North America

The dairy sector in the United States benefits from policy support through interventions including complicated price supports for milk used for manufactured dairy products, classified prices, marketing orders, income compensation and export subsidies. The Canadian system adds supply management, high tariffs and direct subsidies to producers. In the case of the Unites States, a study (Economic Research Service, 2004) evaluating the impact of dairy programmes on markets indicated that the effects are modest, and dairy programmes, while increasing costs for consumers and government, had only a limited impact on enhancing long-term viability of the sector or producers.

Australia ’s dairy deregulation process

In Australia in the late 1990s, the Government and the industry recognized that sector development was constrained by support policies put in place in the 1970s (Harris, 2008). Consequently, an industry reform plan was proposed with the objectives of: i) ensuring competitiveness in international markets; and, ii) avoiding a WTO challenge to the legality of policies. A system of policy measures, such as price pooling and underwriting of guaranteed returns, government controlled marketing arrangements, restrictions on interstate trading of milk and producer-subsidized exports, was abandoned The consultative process consequently subjected all dairy-supporting policies to a regulatory review process and, eventually with the support of a A$2 billion (US$1.6 billion ) industry-restructuring package, moved towards full deregulation of the sector. A clear result of these policy reversals was an increase in the scale and productivity of Australian dairy farms and a more competitive, export-oriented industry.

This cursory review of dairy policies in developed countries shows that sector-specific policy objectives and the measures employed to achieve them need to be clearly formulated and periodically reviewed. As sectors transform and witness structural adjustment in production and marketing systems, this process ensures that policies foster the transformation of the industry. Adhering to decade-long policies can limit the ability of sectors to enhance their competitiveness through restructuring, thus penalizing producers who are innovative at the expense of those who maintain high cost-inefficient operations.

Successfully achieving ambitious policy objectives, as in the case of developed countries, can be hugely expensive – depending on how measures and programmes are implemented. In developing countries, given financial constraints, dairy policies that involve direct support to industries are not so prevalent. The nature of government interventions varies significantly across the Asia region, as revealed in the lessons learned studies. There is strong government support in China and Viet Nam, which have used government-financed credit schemes to encourage the distribution of improved breeds. This has had a significant impact on sector development. However, the success stories are complicated and not widespread. The nature of dairy production provides important sources of daily cash and nutrition to a large proportion of rural producers; in addition, the sector offers important opportunities for employment creation in rural communities. This implies that governments need to be careful and strategic in their intervention selection.

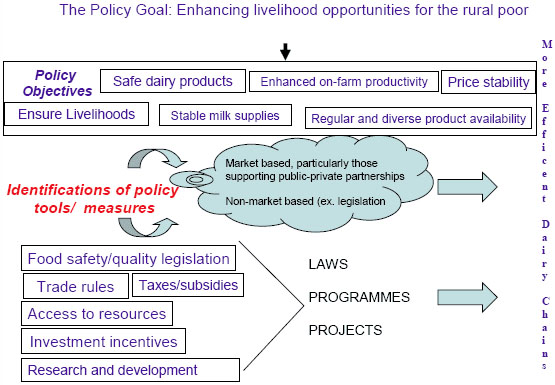

Figure 3: Dairy development planning

Stakeholders along the dairy value chain have very diverse priorities. Table 2 refers to the broad categories of stakeholders; the contextual nature of dairy, particularly in Asia because of its diversity, generates a multitude of different categories of consumers, and producers have different priorities. Whereas a landless owner of a cow in India prioritizes dairy access to milk for his family, a more commercialized farmer in the same region may be concerned about getting a fair price for a quality product.

Table 2: Priority objectives of different stakeholders along the dairy value chain

Consumers |

Processor |

Trader |

Producer |

Safe dairy products |

Better milk quality |

Reduced cost of transport Protection of the raw milk market |

Access to quality services (either publically or privately provided) |

Product value for money |

Increased access to markets (domestic and export) |

Minimize competition with imports |

Fair pricing for quality products |

Variety of products |

Input into policy/advocacy |

Input into policy/advocacy |

Stable farm income/and reduced income risks |

Nutritional products |

Optimizing plant capacity |

Expand and diversify operations |

Access to milk for home consumption |

Readily available |

Stable milk supplies |

Stable milk supplies, regular access |

Increased productivity of animals |

Properly labelling and packaged |

Assured access to quality inputs |

More formalized market role |

Availability to quality inputs |

While there are some commonalities in the objectives of the stakeholders, in many cases the policy instruments used to achieve the objectives can differ in terms of their impact on the stakeholder. For example, a fair price is defined very differently by different stakeholders. Pricing policies that favour one stakeholder over another, such as setting the price of milk without consideration for costs of production for producers, has both short-term implications (farmers will reduce or stop new investments) and long-term impacts (the prices will go up because of supply constraints and shortages of cattle in the long run). This was the case in Pakistan in 2007 when, in the context of rising food price inflation, a milk price ceiling was enforced in Karachi.

The policy instruments

The enabling environment for dairy sector development, particularly one focused on scaling up operations, hinges on clearly articulating policy objectives and on identifying the appropriate tools for achieving them. In developed countries, the use of certain policy instruments has had a differential impact on different stakeholders. Direct support to producers involves government/taxpayer costs, high tariffs on imports raise costs to consumers and supply restrictions limit industries’ ability to respond to changing global demand for dairy products. Similarly, the Karachi case highlights the importance that decisions by governments, in particular the choice of measures or tools that they use to achieve their sector objectives, be implemented with a broader understanding of their direct and indirect impact on stakeholders.

Policy measures can be broken down into three broad groupings: i) those that require legislation and regulatory follow-up; ii) those that facilitate institutional strengthening. These include the development of commodity associations or boards,62 targeted grants for research and development, facilitation of credit to dairy chain stakeholders, etc. And iii) those that are classified as market-based incentives provided by government through public–private partnerships. These could include government-financed grants for private sector research, pro-poor start-up costs for private sector veterinarians interested in working in remote areas, and co-financing of animal insurance schemes.

Table 3: Linking policy instruments to direct impact63 on various chain stakeholder

Policy instruments/impact on |

Consumers |

Processors |

Traders |

Producers |

Controlled by livestock stakeholders |

Food safety/quality legislation |

|||||

Dairy product hygiene |

++ |

+/x |

? |

+ |

No |

Feed safety |

+ |

+/x |

+ |

+ |

No |

Labelling/packing regulations (which includes product definitions) |

++ |

+/x |

x/+ |

– |

No |

Licensing (plants, traders) |

– |

+/x |

x/+ |

+ |

No |

Certification of product standards (such as HACCP) |

+/x |

x/+ |

– |

No | |

Trade legislation |

|||||

Competition policies (anti-monopoly rules) |

– |

+/x |

? |

? |

No |

Tariffs on dairy products (lower) |

++ |

x/+ |

x |

x |

No |

Tariffs on inputs (lower) |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

No |

Special safeguard mechanisms |

x |

+/x |

+ |

+ |

No |

Other legislation |

|||||

Restrictions on inter-regional trade |

x |

x |

+ |

+ |

No |

Tax rebates/credits on investment (foreign/domestic) |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

No |

Subsidies on inputs, other factors of production |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

No |

Land tenure, access to water and other resources |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

No |

Food vouchers for the poor |

++ |

+ |

– |

– |

No |

Legal recognition of supply/marketing contracts |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

No |

Legal recognition of commodity associations |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

No |

Decentralization of livestock services |

– |

+/x |

+/x |

No | |

Institutional support |

|||||

Trade/export facilitation |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Yes |

Cost-sharing on generic promotion of milk |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Yes |

Credit guarantees for market participants |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

No |

Research and development; this could include one-off grants to private sector |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

No |

Establishment of commodity bodies |

– |

x |

+ |

+ |

Yes |

Financial support to school milk programmes |

++ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Market-based incentives provided by government |

|||||

Tax credits/or concessional payments to processors/private sector for services provided by in the areas of:

|

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

No |

Government-financed start-up grants for private veterinary practices in rural areas. |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

Yes |

++= very position, + = positive, x = negative, – = no impact, x+= negative or positive | |||||

A review of possible measures for achieving policy objectives is presented in Table 3. While mainly illustrative and not comprehensive, the table includes possible policy measures as options for achieving the objectives identified by workshop participants as supportive of sector development. The table reveals that some policy instruments are more favourable to the interests of various stakeholders. For examples, food safety or quality legislation that sets milk hygiene standards, which are enforced by ordinances and regulatory inspection at the level of plants and traders, is favourable for consumers concerned about food safety of milk products. However, for poor consumers, both in urban areas and those consuming raw milk supplied by traditional markets in rural areas, legislation and the way that it is enforced could have a negative impact on incomes (as milk becomes more expensive because of higher processing costs) and nutrition (if milk becomes less accessible).

Similarly, the impact of this food safety legislation example will have differential impact on processors, assuming that the larger ones who have higher standards will be impacted differently than those who have higher relative costs of compliance to ensure adherence to the new standards. In fact, as indicated in studies in the United States, the introduction and enforcement of higher standards (such as making Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points-HACCP, mandatory) potentially leads to a consolidation of the industry as smaller firms opt to sell their operations to those with larger operations and larger economies of scale.

Policy responses that seek to control markets through ceiling prices, forcible procurement or direct government involvement in production or marketing activities (in order to ensure food security and access to food) will, in most cases, lower prices and constrain potential output gains. And thus, they will adversely affect producers’ livelihoods. Any policy instrument that affects price levels along the chain, from retail price ceilings to supply management systems in Canada and those that link producer prices to the costs of production, have ripple affects along the dairy value chain and affect the long term competitiveness and viability of the industry.

It is also clear that the key role played by government is mainly legislative and regulatory, although government can strategically engage the private sector in market-based solutions that are tailored as a cost-effective alternatives or complements to legislation. Constructively engaging the private sector early in the process through the provision of attractive financial incentives, such as tax rebates and cost-sharing arrangements, is crucial for ensuring the development of the sector. Government should be aware of the private sector’s role in addressing many of the problems affecting efficiencies of dairy chains. Supportive private services include targeted extension, animal health, AI services, the facilitation of chain-based financing/credit guarantee schemes, the establishment of traceability and quality assurance services, etc.

|

Box 2: “The score card” approach Sally Bulatao, Former Chairperson, National Dairy Authority Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems identify the efficiency and effectiveness of a project or a programme. The National Dairy Authority (NDA) of the Philippines adapted a “score card” approach in which there are monthly reports on indicators that address final outputs (milk production, number of dairy animals, etc.) as well as measures of performance based on the Dairy Development Plan (breeding and calving numbers, volume of milk processed, milk sales, etc.). Together with the managers and technical people in the National Dairy Authority, indicators were identified that best capture the results of operations. The indicators had to correspond to the main programme components: herd build-up, business enhancement, quality assurance and school milk provision. The final score card had to fit one page to be readily available for public use. Each of the indicators on the final score card has corresponding subindicators monitored at the field offices. For example, milk production for the month would be on the final one-page score card, but this indicator is supported by subindicators of milk production in different types of farms and linked to areas covered by assigned extension workers. The M&E system aims to help the agency: i) review progress; ii) identify problems and causes of slack in achieving targets; and iii) make necessary adjustments as needed by resource availability and ground-level feasibility of planned activities. Annual targets are set in a year-end planning conference and reviewed in a mid-year planning meeting. Based on the unit scores, the NDA presents its top-ten achievements in its annual report. Other achievements at the field level are documented in each programme, such as keeping the number of non-milking animals low, ensuring timely payment of animal loans, increasing the number of children covered by the school milk provision through contracts with local governments. On an annual basis, the benefits realized per peso of government funds invested in dairy development are reported. The subelements of the programme components generate the achieved dynamism. For example, while herd build-up is a mainstay component of the dairy programme, the subprogrammes that tailor animal loans to the industry context drive better performance. One example is the Save-the-Herd (STH) Programme to save dairy animals from being sold outside the dairy zone. This allows dairy farmers who want to sell their animals to pass on the animal to another dairy farmer who enters into a caretaker arrangement with the cooperative or an NDA field office. In the monitoring system, the number of animals under the STH is tracked. While having consistent programme components, the dairy plan is subject to performance checks through the score card so that annual adjustments may be made to ensure reality-based goals. This process spurs the conceptualizing, designing and packaging of better targeted activities. |

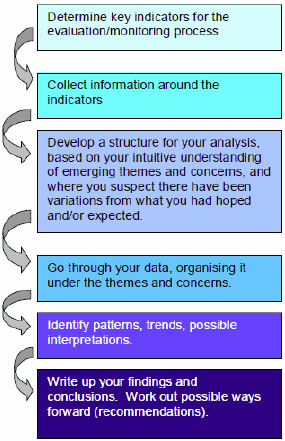

Figure 4: Steps involved in monitoring and evaluation (Shapiro, Janet)

Despite declines in 2008, dairy prices remain higher than historical levels. This has induced renewed interest in dairy development in the Asia, particularly in recognition of the nutritional and livelihood importance of milk in rural communities. Nearly 80 percent of the 247 million tonnes produced in Asia in 2007 was supplied by smallholders.

The test for stakeholders in the region is to foster sector growth, one that is inclusive of smallholders, through the development of an enabling environment. This requires generating a sector-planning process that provides a road map for sector development that has buy-in from the private sector and is representative of the priority concerns of stakeholders, large and small.

Most of the policy measures that could support dairy development are not under the control of a ministry or department of livestock. Rather, they are the responsibilities of other ministries, such as commerce, trade, heath or industry. This implies that in the development planning process, other stakeholders need to be brought early on into the planning process. As well, a host of other considerations need to play into the decisions on how to support sector development. While socio-equity issues can be reviewed, recognizing that there is a diverse set of consumers and producers, the impact of policies on the environment also needs to be considered.

The challenge is to translate the planning process and final strategy document into a vehicle for action. This requires a comprehensive process that explicitly relates implementation modalities to clear action plans with identified responsibilities of selected champions. The more difficult challenge is to identify policy measures that can effectively respond to policy objectives. Limited by financial constraints, dairy stakeholders need to critically evaluate the potential impact (both human and economic) of policy combinations to determine which are acceptable along the chain – while recognizing the overall vision for sector development. Private sector engagement and endorsement of the process is one of the essential ingredients for success in this process.

58 The meeting took place in Bangkok in November 2008 and was attended by approximately 40 experts from the region. Further documentation on the meeting and participants can be found on the APHCA website: http://www.aphca.org/workshops/Dairy_Workshop/Strategy.htm. More details can also be found in the workshop publication, “Practical Considerations in Designing Strategies and Policies for Dairy Sector Development”.

59 See website above.

60 A champion is someone who provides leadership and ownership of the planning process. It can be a person or an institution but should, most likely, be part of the political process.

61 The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development

62 A board is occasionally a parastatal organization linked to government that assumes some type of regulatory, oversight role in industry development whereas a commodity association is more representative of broader stakeholder interests and serves more of an advocacy role for the sector. The establishment of commodity bodies requires a clear legal basis recognizing their existence, role and authority.

63 “To affect or influence especially in a significant or undesirable manner”; some interventions can have indirect impacts as the policy feeds through the chain, particularly through impact on prices. However, this table addresses the direct impact of the policy measure.