Tuesday, 22 April 2008

Organizers

Regional Community Forestry Training Center for Asia and the Pacific (RECOFTC) and the Asia Forest Network (AFN)

Introduction

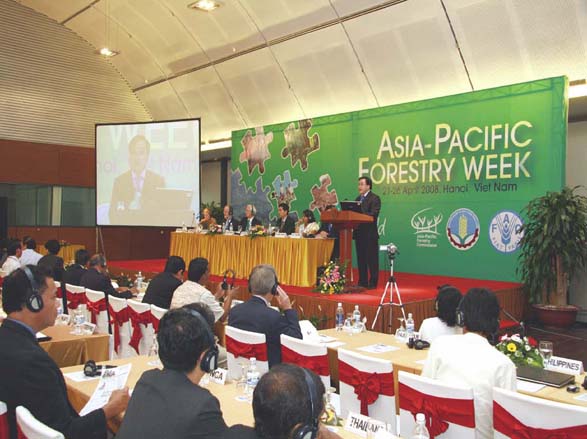

The first-ever Asia-Pacific Forestry Week (APFW), held around the 22nd Session of the Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission (APFC) in Hanoi 21-25 April 2008, brought together individuals from governments, non-government organisations, research institutions, regional and international networks, UN agencies, and the private sector to share perspectives and seek solutions to the most challenging issues facing forests and forestry today. During the week, each day was devoted to a different element of the three pillars of sustainable development: social, environmental and economic. This synthesis captures some of the richness of the debate from the social session focusing on forests and poverty issues, as a way to share the key points and recommendations with a wider audience.

The session, organised by RECOFTC, with the support of the Asia Forest Network (AFN) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), questioned some of our assumptions and deepened both conceptual and practical understanding of fundamental issues affecting people, forests and human well-being. Four presenters examined different aspects of the challenge from a range of perspectives – from the local to the global level. The issues raised were then debated by the audience and five panellists, chosen to represent different interests. In the afternoon, the APFC reflected on the morning’s debate as the basis for recommendations for action.

Background

The FAO State of the World’s Forests 2007 reports that the relative contribution of the forestry sector to GDP in the Asia-Pacific region has been declining for the past decade. The region is now the biggest net importer of forest products in the world and the largest exporter of non-wood forest products. Variation in the net rate of change in forest area is much more pronounced in the region. Several countries are losing forests at rates exceeding 1.5 percent per year (e.g. Indonesia and Myanmar), among the highest rates of loss in the world. At the same time APEC leaders, in 2007, made a commitment to increase forest cover in the region by 20 million hectares by 2020. Forest conservation and management have now returned to the centre stage of the global debate on environment and development due to the recognition that forest loss and degradation result in more greenhouse gas emissions than the global transport sector.

The Asia-Pacific region has emerged as the global epicentre of economic growth and change. With this growth, along with increasing regional integration, come increased social mobility, rise to middle-income status and growing inequality (RECOFTC, 2008). Models of development are being challenged and no more so than in the forestry sector

Little is known about the informal forestry sector, as national statistics on income and employment capture only the formal sector. “We often hear that one billion people are dependent on forests, but the reality is that the statistics and numbers are extremely poor. It is shocking that we are moving into the 21st Century and don�t really know how many people live in forests” (Marcus Colchester). Many studies indicate that the informal sector dwarfs the formal sector. It provides benefits especially for poor people who are the main subject of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). However, people in the informal sector frequently work in the context of ill-defined rights where there is little incentive � if any � to manage natural resources sustainably. Under these circumstances, the challenge laid down at the social session was to question whether:

Under present and foreseeable economic and social trends in the Asia-Pacific region, can we achieve sustainable forest management and better realise the potential of forests and forestry to contribute to improved human well-being?

At the heart of this question lie the still relevant and important statements made by Jack Westoby, which have shaped much of international debate on forests over the last four decades:

“Forestry is as much about people as it is about trees�.

BUT

�What has forestry done to improve the lot of the common man, of the peasant?

Precious little.” (Westoby, 1977 & 1989)

Six propositions

For decades, foresters, conservationists, and social activists have been making the case that forests and forestry matter � to national economies, rural development and poverty reduction, environmental and cultural sustainability, biodiversity conservation, flood control, human health, conflict prevention, and most recently, climate change. And yet forests continue to be degraded and converted to other uses at a rate that implies that they don�t matter very much at all to those with the power to control such processes. We have had numerous overlapping and often contradictory paradigms to making forestry matter (Table 1). All of them have done little to slow the rapacious degradation of resources or to reduce the poverty.

Table 1 Changes in paradigms

|

1960s ‘Trickle-Down’ |

Forestry for industrial development |

|

1970s ‘Basic Needs’ |

Forestry for local community development (Westoby model), oil crisis, fuelwood crisis |

|

1980s ‘Participation’ |

Social forestry, community forestry |

|

1990s ‘Public Sector Reform’ |

Institutional reform, collaborative, participatory forestry |

|

2000+ ‘Good Governance’ |

Focus on corruption, illegality, decentralisation |

|

2000+ ‘MDGs and Poverty’ |

Poverty, livelihoods |

|

2007+ Renaissance Forestry |

Forestry crisis, climate change, dramatic energy and food price spikes |

Do forests matter? The reality

The significance of forests has been overstated with respect to some objectives and benefits, and underappreciated with respect to others – but the key question is for whom are forests important? As the evidence shows so far – for many people forests don’t matter but for some forests matter hugely. They provide a variety of ecosystem goods and services: timber, fuelwood and forage, fruits and vegetables, bushmeat and medicines, materials for handicrafts, hydrological services, pollination services, climate regulation. For those living in or close to forests, dependent on them for a range of livelihood and other services, they are of crucial importance; many urban people may view forests only as a source of timber or a resource ready to be converted to financially more lucrative land uses. Rarely is their importance as a standing source of biomass recognized and appreciated. Forests may even be viewed as a barrier to development.

Although we can talk about the effects of deforestation and forest degradation on people, there is nothing more powerful than hearing from one of the people who is directly affected by our actions and decisions. Norman Jiwan is a member of the Dayak Kerambai tribe of West Kalimantan, Indonesia; he illustrated the profound effects on his people of decisions, made in distant places, and changes in political regimes over the last 60 years. The Kerambai’s customary lands and forests have been challenged by a succession of logging concessions, rampant illegal activities and the expansion of oil-palm plantations, threatening their social and cultural integrity as well as their livelihood security.

As Norman Jiwan reminds us, for his people, “development without justice is not development, it is exploitation.” Their entire cultural, social and economic system depends on the forests; their human and environmental rights bulldozed actually and metaphorically. For them forests matter very much and for all of us forests should matter more than they currently do.

Poverty is not understood

“Development strategy needs to move beyond the bounds of its present emphasis on economic growth – hundreds of millions of people are born poor and die poor in the midst of increasing wealth. Chronically poor people need more than ‘opportunities’ to improve their situation. They need targeted support and protection, and political action that confronts exclusion. If policy is to open the door to genuine development for chronically poor people, it must address the inequality, discrimination and exploitation that drive and maintain extreme poverty.” CPRC 2005:vi

We have not understood poverty. We do not understand who is poor and why. We have started in the wrong place: with the forests and forestry and trying to justify their ‘pro-poorness’ or making them more pro-poor. We should have started with people and understanding the conditions that form and reproduce their poverty. Our attempts to place more control at the community-level have often led to increased elite capture of many of these schemes, with a further disenfranchisement of poor people.

One of the major issues about any ‘pro-poor’ forest policy is the problem of identifying and targeting the poor. This is rarely done; the reasons being both pragmatic (it is very difficult) and also political (it is not usually desired by elites). The word ‘poor’ is itself a problem covering a multitude of different types of people in different degrees of poverty.

So if we can’t use short hand such as the word poor, how are we going to describe and understand poor people’s relations with forests? There are three main ways of understanding poverty:

Policies have to be able to respond to the spatial poverty traps – sites of chronic poverty in remote rural areas. Policies need to respond to the livelihood challenges of those people in remote forested areas who have little other than forests on which to build their livelihoods. In such areas, chronic dependence means that changes in policy that affect forest usage have more profound effects on livelihoods than in those areas with diverse livelihood opportunities. Across all areas there are those who suffer temporal vulnerabilities for whom forests and tree products may provide seasonal and/or life–cycle safety nets. The third level of vulnerability is suffered either by particular groups in society, often indigenous groups, excluded groups (because of caste or ethnicity) or within communities because of gender, caste or life – cycle positioning. The effects of policy change on these groups are again different from others in the same community who are not socially or economically excluded. For some, all three levels of vulnerability are in operation at the same time. Structural vulnerability is the most profoundly difficult to change through policy processes and is particularly resistant to change through technocratic solutions without due political process and clearly defined rights. Unless we understand the different dimensions of poverty, our policies will continue to reinforce poverty rather than provide the necessary changes to help the poor to lift themselves out of poverty. The implications of this analysis are three–fold:

Change is driven from outside the forest sector

The main drivers of change lie outside the forestry sector and our narrow preoccupations with forestry. Advocates of sustainable forest management (SFM) have erred in focusing their efforts within the forestry profession and on forestry-related institutions, although forestry agencies continue to focus on technical aspects and remain a barrier to change, finding it difficult to recognise and engage with the increasing complexity of forestry and the need to think across sectors. So why is it that after 60 years of economic change in Indonesia we are still rehearsing the same arguments? If we look further into the region – the debate on the future of forests in Asia and the Pacific held by the forestry community tends to focus on recurring themes and major barriers to bringing about SFM, such as constraints to financing SFM, massive and diffuse corruption and the persistence of outdated and unenforceable laws. We are all familiar with them, perhaps even comfortable, allowing us to continue to bemoan their existence but not propelling us into any action to challenge and change them. In the meantime, emerging drivers of change and new realities have made the headlines, sometimes hardly noticed by those deliberating the removal of old barriers. These new drivers already have had a significant impact on the fate of forests, and some of them will have even more so in the future. There is great urgency to take their potential implications seriously. Examples of new drivers include:

Changes in governance are essential

Fundamental changes in governance – including both substantive and procedural rights related to forests – will be necessary for people to whom forest matter most. Indigenous peoples have limited protection against external forces that determine ownership and use of their land. Despite the large amounts of money and attention that has been devoted to public sector reforms, policy development and implementation continue to be weak, plagued by the persistence of unenforceable regulations.

In Asia and the Pacific, the forest area actively managed by tens of millions of people exceeds 25 million hectares and is increasing. Decentralized bureaucracies are often weak and politicized, and unable to address the real needs of local communities. Their decision making may also be less far-sighted and increase the speed of deforestation and forest degradation. Some of the current attempts to recentralise and to further bureaucratise forestry may lead to further disenfranchisement of those populations whose livelihoods rely on forest access. At the same time, it will have negative impacts on forest conditions. There is still need to reorient and reform national forestry agencies and policies. Capacity building initiatives at all levels are required for foresters to facilitate the engagement of local people in forest governance and management. This is not an easy task as evidence shows that the huge effort that has been underway for years to do just this had relatively limited success to date.

Forestry and foresters don’t matter

Clearly they do but only if the governance structures are changed and foresters and forestry becomes part of the wider institutional framework. Although foresters cannot change the direction of the emerging drivers of development, continuing to neglect taking them seriously and focusing on conventional barriers only, means that deliberations on how to bring about SFM will remain stuck in a blind alley. We should also question how much forestry has been part of the structures that sustain social exclusion – marginalising people and reinforcing the structures that exclude (Marcus Colchester). Moving on from this, the words of Westoby (1968) are as relevant today as they were 40 years ago and remind us forcefully of our moral responsibilities: “foresters are agents of change – social and economic.” We have a responsibility to recognise the importance of human well-being, as well as the well-being of forests.

Climate change – a moment of opportunity

The international community’s new appreciation of the role of forests in mitigating climate change provides an historic opportunity to shift the political economy of forests. Debate at the international level, in forums where forests are never usually discussed, is now dominated by the role of forests in climate change and its mitigation. New mechanisms and aid architecture are being put in place to finance sustainable forest management – an opportunity indeed to ensure that the lessons learnt from 40 years of practice can inform these debates held among people that have not been intimately involved in forestry practice and learning. Critically it is a moment to ensure that the social dimensions of carbon financing for forestry are carefully understood to prevent negative effects on the poor. A particular issue concerns the protection and assertion of the rights of local people as the sellers of carbon.

Improving what we do – making it possible to combine SFM and improved human well-being

If we accept these six propositions and the complex arena of drivers of change, it is clear that we have much to do to change the nature of the debate and the outcomes both for improved human well-being and SFM. The current global debate on climate change provides an important moment of opportunity to influence the course of policy and practice. Based on what we have learnt there are seven areas where we have to improve our understanding and practice:

If we are going to make any difference at all we must invest in understanding what makes people poor and traps them in poverty. We should put poor people and their vulnerabilities at the centre and not the forests. We must understand the complexity of power relations that affect people’s capacity to secure access to resources. We must also recognise the high risks attached to the poor challenging the power relations that threaten their livelihoods and rights to forest resources. Above all, we need to accept and implement wider livelihood-based approaches linked to governance arrangements that promote structural transformation (at local, national and international levels).

Hope for the future?

As the recent food and oil price hikes have illustrated, globally poverty and food security challenges will not go away in the near future. The importance of engaging in current debates and making good use of the rich forestry development experiences is essential to ensure that those who are already threatened by our global actions are not further driven into poverty and insecurity. We must take these lessons and apply them in a way that is morally responsible and sensitive to the context of individuals and their rights.

What is clear from the discussion and debate is that it will be a difficult and contentious process to increase forest cover in the region by 20 million hectares, as proposed by APEC; in particular when we still continue to disagree on the definition of ‘forests’. As Marcus Colchester asked “does it include oil-palm, large timber estates? The target can be achieved but people will be massively marginalised in the process.” The importance of local determination was emphasized during the debate by Yati Bun and Modesto Ga-ab. Rather than signing-up to other people’s targets, each country should determine its own targets based on an understanding of local and national needs and contexts. Honesty about what is possible should underpin the approach to future forest development: “it doesn’t work to adopt other people’s targets; we should know what can work in our own country and start from within. We need to have decent processes of consultation that really bring communities into the debate” (Yati Bun). Returning to our opening challenge is it possible to combine SFM and human well-being? Yes it is, but only with a major effort to restructure the way we work. Most importantly, we need to take seriously our moral responsibility for ensuring people’s rights. Without attention to recognizing and acting on the complex reality illustrated in the seven areas of work, it is clear that we will continue to reproduce the concluding statement made by Ken Piddington:

“My painful conclusion is that the preconditions for sustainable forest management simply do not exist at the present time, with the exception of isolated cases where circumstances have combined with political will to create effective insulation from the pressure of commercial interests.”

References

APFC. 2008. Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission 22nd Session. Draft report. FAO, Bangkok.

CPRC. 2005. Chronic Poverty Report 2004-05. Chronic Poverty Research Centre, University of Manchester.

FAO. 2007. State of the World’s Forests Report 2007. FAO , Rome

RECOFTC. 2008. Is There a Future Role of Forest and Forestry in Poverty Reduction? Thematic report prepared for the Second Asia-Pacific Forestry Sector Outlook Study. Regional Community Forestry Training Center for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok.

Westoby, J. 1968. The Forester as Agent of Change. In: The Purpose of Forests (1987), Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

Westoby, J. 1989. Introduction to World Forestry. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

Acknowledgements

This synthesis, written by Mary Hobley with inputs from Thomas Enters, and Yurdi Yasmi, draws on the presentations, subsequent debate and questions from the audience.

Wednesday, 23 April 2008

Organizers

Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), the US Forest Service (USFS) and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

Introduction

Dr Susan Braatz, FAO

Dr Braatz commenced her introduction by stating that forests are currently high on the global agenda, as reflected in the attention given to forests at December’s Bali COP13. There were 3 key decisions that came out of Bali, that were especially relevant to forests:

Dr Braatz then outlined the format the plenary would follow (ie. Mitigation & Adaptation) and introduced the first session.

Session 1: Climate change mitigation

Entering Readiness Phase for Full REDD Implementation by Dr Daniel Murdiyarso, Environmental Services Program, CIFOR (Indonesia)

Dr Murdiyarso echoed Dr Braatz ’s comment that forests are currently high on the global agenda, and said that had been the case (in varying degrees) since the early 90s.

Setting the scene

If Indonesia could curb peatland fires, it could potentially earn billions of dollars from REDD projects. Tens of thousands of hectares of peatland forest have been cleared to make way for plantations in Kalimantan, Indonesia (Leon Budi Prasetyo).

Criteria for readiness

1. Methodological issues must be addressed (eg. monitoring and accounting).

2. Underlying causes of deforestation must be identified. This includes market failures (eg. commodity prices) and governance failures (eg. land rights issues).

3. Demonstration Activities (both national and sub-national) must be initiated. Also need to look at other Payments for Environmental Services (PES), beyond carbon.

4. Baselines (or reference levels) must be set.

Conclusion

In addition to the above criteria, significant capacity building is needed at a local and regional level, and a national registry must be established that is supported by strong governance.

Dr Murdiyarso’s presentation was followed by a panel discussion.

Panelists

Dr Nur Masripatin, FORDA, Ministry of Forestry of Indonesia

Dr Nguyen Hoang Nghia, Forest Science Institute of Vietnam

Dr Kanninen commenced the discussion by inviting each panelist to comment briefly on Dr Murdiyarso’s presentation.

Dr Nur:

Dr Nghia:

Dr Kanninen then asked the audience how many participants have been involved in national level discussions about REDD? Approximately 10% raised their hands. He made the comment that the window of opportunity to demonstrate that REDD is a viable option post- Kyoto is not big. He then invited comments and questions from the floor.

Questions from participants

Response from panelists

Dr Murdiyarso:

Dr Nur:

Questions from participants

Response from panelists

Dr Murdiyarso:

Dr Nur:

Conclusion

Dr Braatz concluded the first session by recapping on some of the key issues and opportunities discussed:

Session 2: Climate change adaptation

Dr Allen Solomon, National Program Leader for Global Change Research, US Forest Service, introduced the second session by explaining that adaptation to climate change is closely linked to mitigation of climate change and, therefore, this second session would complement the first. He then introduced the second presentation:

Vulnerability of Forests to Climate Change: Current Research in Tropical Areas by Dr Boone Kauffmann, Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry, US Forest Service.

Dr Kaufman commenced his presentation by pointing out that tropical forests cover only 10% of the earth’s surface, yet contain around 40% of the carbon that resides in terrestrial vegetation. They also harbor between half and two-thirds of the world’s species.

Dr Kauffmann’s presentation was followed by a panel discussion involving: Dr Rex Cruz (University of the Philippines), Dr Solomon (USDA), Dr Bruno Locatelli (CIFOR-CIRAD ) and Dr Boone Kauffmann (USFS).

Dr Cruz:

Dr Locatelli:

Dr Solomon:

Questions from participants:

Response from panelists:

Dr Kauffmann:

Dr Locatelli:

Dr Solomon:

Conclusion

Dr Susan Braatz, FAO:

Thursday, 24 April 2008

Organizers

Asia Forest Partnership (AFP), the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), the UK Department for International Development (DFID), the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) and The Nature Conservancy (TNC)

Introduction

Boen Purnama, Secretary General, Ministry of Forestry of Indonesia; Chair, United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF) 8 Bureau.

Dr Boen welcomed the audience on behalf of the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry and congratulated the Asia Forest Partnership (AFP) for organizing the event – “this has been an excellent effort to elevate participation of the private sector and civil society in achieving sustainable forest management.”

Timber trade, forest law compliance & governance are all central themes of AFP. Although deforestation does show some signs of decline, it is still “rampant” in parts. It is a very difficult issue to address, as there are a range of actors involved with range of interests, many of which wield a lot of power. Indonesia has undertaken many initiatives to help combat illegal logging (eg. FLEGT), but this complex problem requires a concerted and committed effort, and not just from government.

There are a number of instruments to drive this effort, of which trade is one. The challenge is to find a balance between the costs of such instruments and their impact. “The UNFF would welcome input from this dialogue.” Participants were then shown a documentary film - The Forest of South Sulawesi – which won two categories at the 31st International Wildlife Film Festival 2008 Awards. The film documents the local community’s innovative and cooperative approach to combating the illegal timber trade.

Moderator

Rico Hizon, BBC Asia Business Report

Mr Hizon enthusiastically greeted the participants, and posed two key questions that would underpin the Dialogue: Can illegal trade in timber be eradicated? Are developed countries taking initiative to play their part? He promised that “WE WILL FIND THE SOLUTIONS!”, but only if there was participation from all sectors of the audience. Mr Hizon then introduced the first of five presentations. Large quantities of illegal timber are transported by river in Indonesia (Agus Andrianto).

Session 1: Presentations

No. 1: Actions by consumer countries to tackle the international trade in illegal timber

Federico Francisco Lopez-Casero, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Japan

Dr Lopez-Casero commenced his presentation by pointing out that round wood imports into traditional markets (eg. EU & USA) are decreasing, while for a number of emerging markets throughout the Asia-Pacific region they are increasing (eg. China & Viet Nam).

What consumer countries are doing?

Beyond 2008

No. 2: Ensuring the sustainability

Amir Sunarko, Sumalindo Lestari (SL), Indonesia

Mr Sunarko commenced his presentation by providing a brief overview of Sumalindo Lestari.

Sumalindo is committed to:

No. 3: Are timber markets changing? If so, what are the implications for industry, forests, people and governments?

Moray Isles, Dalhoff Larsen & Horneman (DLH), Viet Nam

Overview of DLH:

DLH is a Danish-owned group that has been trading and producing timber and wood products since 1908. DLH works globally in 37 countries, has an annual turnover of around US$1.5 billion, and employs around 4000 staff.

Viet Nam industry market indicators

Are markets changing?

Implications . . .

All industry players must:

No. 4: Is legal and sustainable timber production important? Who for, and why?

Timer Manurung, Telapak, Indonesia

No. 5: Certifying community forestry in Papua New Guinea

Caroline Imun, Foundation for People and Community Development (FPCD), Papua New Guinea.

Overview of PNG

Forest certification

Benefits & challenges

Government must:

Conclusion

Session 2: Open forum

Following morning tea, Mr Hizon opened the Dialogue to comments/questions from the floor.

Following is a broad summary of some key comments from participants, and responses from the five panelists.

RH = Rico Hizon, FL = Dr. Federico Francisco Lopez-Casero, AS = Amir Sunarko, MI = Moray Isles, TM = Timer Manurung, CI = Caroline Imun

PNG: Has anyone here ever had any help from their government?

Thailand: Questions statement from TM that people in Thailand can buy illegal logs from government officials. Do you have any evidence?

RH: Despite all these standards/policies/measures that are in place, illegal logging figures continue to increase! Why?

MI: Despite the existence of laws, people are always going to circumvent them.

FL: International certification schemes require mutual recognition.

Floor: (addresses CI) Corporate Social Responsibility – what is the level of commitment to help forest people? And is it an approach that can work to help implement SFM?

CI: FPCD addresses social, environmental and economic concerns through certification.

Malaysia: Outlines his intimate knowledge of each element of the panel (ie. past, present & future employment links). Points out that the panel contains representatives from two companies that have chosen to commit to sustainability, and emphasizes that this commitment requires the collaboration of senior management, which can take a very long time. Given that it is accepted we must act fast, how on earth can this be implemented across the board and across the region? Even with the commitment, the logistics (eg. auditing) are immense.

AS: Recommends companies collaborate with NGOs for advice, credibility and stability. Identification to implementation can be achieved in just 3-5 years.

MI: Points out that merely complying fully with current standards and policies etc can go a long way towards improving a company’s sustainability.

Malaysia: Applies the metaphor of choosing to treat cancer by cutting off your head! You have to treat problems at the source. What has Telepak done to help tackle these problems, other than merely report? How can you say that 70% or 80% of timber going from Indonesia to Malaysia is illegal? Just because it is uncertified doesn’t mean it’s illegal. Sorting out certification is Indonesia’s responsibility. We are just buying timber, it’s up to Indonesia to sort out where it comes from.

TM: Malaysia always says that it’s Indonesia’s problem. And tries to delay. There are ongoing negotiations for an MoU between Malaysia and Indonesia, but the latest draft from Indonesia is unsigned by Malaysia. Most of the problems related to trade of illegal timber between Malaysia and Indonesia are Malaysian!

Japan: Why doesn’t anybody point the finger at Singapore, even though it imports large quantities of illegal timber?

TM: We have a report on Singapore, and yes they import large quantities of illegal timber. They also harbor criminals from Indonesia as there are no extradition agreements.

MI: (regarding potential for private sector to support small-scale, sustainable industries, like PNG) Yes, but it’s important to link suppliers with buyers and identify an end use. The challenge for a small producer is logistics – ie. getting the supply to the buyer, often from

remote locations for a reasonable price. A potential solution could be to make agreements with large-scale freight suppliers conditional to providing cost-effective solutions for remote and emerging markets.

Australia: (i) Media articles are good for raising awareness, but often repeat statistics that may be inaccurate or out-of-date. (ii) How can sustainable operators encourage colleagues (or competitors) in private industry to do follow their lead?

AS: There are benefits (or otherwise) to be gained for all operators from an industry-wide reputation.

Conclusion

Dr Dicky Simorangkir, Rare International and Dr David Cassells, TNC:

"Caring hand of an orangutan as being guided by a worker in the National Park Cisarua, Bogor"

William Wirawan 2008