The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA) does not have a precise definition, but rather, can be described as “a way of thinking about the objectives, scope and priorities for development in order to enhance progress in poverty elimination”[19]. The SLA is comprised of a development objective, and an analytical framework that provides a means of understanding the factors that influence the ability of people to achieve SL in particular circumstances. The third component of the SLA is a set of principles, which are at the heart of the approach.

The Key Principles of Sustainable Livelihood Approaches....

|

According to the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach, the key principles of poverty-focused development should be:

|

As an analytical framework the SLA is based around the analysis of five capital assets (human, physical, financial, natural and social) upon which people draw for their livelihoods.

Direct FAO engagement with the SLA framework supported by DfID began with the Forum on Operationalising Sustainable Livelihoods Approaches held in Siena in March 2000. This forum provided a platform for an exchange of experience and perspectives on SLA between DfID, FAO, IFAD and the WFP as well as a number of independent resource people using the SLA. The promotion of sustainable livelihoods is a key objective in the FAO Strategic Framework for 2000-2015 and the potential of the SLA in supporting this objective has come into increasing focus. An inter-departmental Livelihood Support Programme (LSP) was established within FAO with the financial support of DfID. The objective of the LSP is to improve the impact of FAO interventions at country level through the effective application of SLAs to better support the livelihoods of the rural poor. The main value-added of the SLA is that it offers a way in which to understand the complexity and substance of poor people’s livelihoods. At the current moment, the SL approach is relatively untested in terms of performance in the field, so it is uncertain as to how successful it will be when fully implemented.

The structure and components of this approach are not easy to identify because they have been variously applied by different institutions and in different regional contexts. The Farming Systems approach has a different approach in the Francophone and Anglophone context and has a different structure and components in the way it has been applied in Latin America, Asia and Africa. However probably the main component of all the variants is the diagnostic process. The concept of the farming systems is based on the existence of individual farming systems with broadly similar resource bases, enterprise patterns and household livelihood constraints for which broadly similar development strategies and interventions would be appropriate. The farming systems approach considered in this paper is that version utilised by Dixon et al[20], which takes the following components as central to the diagnostic process:

Natural resources such as land, water and common property

Climate and biodiversity

Human capital

Social capital

Financial capital.

The strength of the approach is considered to be its ability to integrate a multi-disciplinary analysis of production and its relationship to key biophysical and socio-economic determinants of the farming system. These include the available natural resources, climate, technology, the market, policies, institutions, information and human capital. The latest versions of the farming systems approach have moved well beyond the farming system in scope, taking into account social structures and policies in the local to global hierarchy. The objective of this version of farming systems is to sustainably improve the living standards of the small farmer and to contribute towards their empowerment in decision-making.

The nine fundamentals of the Farming Systems Approach are[21]:

1. Small-farmer orientation

2. Farmer participation

3. Location-specificity of technical and human factors

4. Problem solving approach

5. Systems orientation

6. Interdisciplinary approach

7. Complementarity with component research

8. On-farm trials

9. Feedback to shape future agricultural research and policy.

Integrated Rural Development (IRD) emerged alongside the ‘small-farmer first’ narrative, which begins with the recognition of agriculture’s a key role in overall economic growth, through the provision of labour, capital, food, foreign exchange and a market in consumer goods for nascent industrial sectors[22]. The notion of rural growth linkages, that is of the small farmer as a central driving factor in the growth of labour-intensive non-farm activities, was a central part of this strategy.

A key component of the approach was the idea of the ‘big’ target. IRD aimed at major transformation of the structures of rural development. The projects initiated under IRD were specifically aimed at improving production and living conditions of small traditional farmers through multi-sectoral policies and agencies. The partners for projects initiated through the IRD approach were usually national and local governments. Projects tended to be managed by a large dedicated project management unit, which posted interdisciplinary technical teams in the field. A primary importance was also given to technicians and researchers; indeed there was a close link between IRD and farming systems research. The notions of local capacity building ad local institutional sustainability were not given much importance in IRD projects. Thus, IRD was about the provision of infrastructure, training, services and inputs, without placing any importance on the priorities of the beneficiaries of these programs. These were all provided in the hope, rather than the expectation, that the poor would benefit. IRD completely failed to take into account the policies and practices that may prevent local people from taking advantage of the improvements in infrastructure and services.

In the late 1980s and 1990s IRD came to be described as a top-down and blueprint approach. This approach now carried negative associations, drawn largely from the abundant evidence of the failure of IRD projects to achieve their transformative objectives. At the present time, the IRD approach to rural development has been almost entirely discredited, although, current approaches, such as the SLA, GT, etc. have all built on the notion of integrated interventions for poverty alleviation.

The gestion de terroirs (GT) approach to rural development has been used almost exclusively in Francophone West Africa. It emerged from the recognition that previous rural development projects, primarily IRD, had failed to make an impression on poverty in the region. There was a widespread awakening to the reality of the situation within the Sahel region, with an acknowledgement that the environmental problems in the region were dependent upon space, time, and various inter-connecting economic, demographic and institutional factors operating at national, local and international levels[23].

The gestion de terroirs approach can be seen as an attempt to transfer the management of control and access to natural resources from the grasp of the central government to local people. However, the first generation of GT projects simply emphasised the technical aspects of environmental protection and natural resource management, while the priorities of the local populations continued to remain focused on other things, such as credit, water, health, etc[24]. A change was can be seen in the early 1990s when the priorities of GT projects began to be drawn in line with those of the locals themselves. Thus, the project terms came to be increasingly defined by the rural communities involved in their implementation. However, it must be noted here that this still did not solve the problem of the transfer of power from government to local population, which has remained largely haphazard in most West African countries, leaving a state of confusion around the question of who controls access to natural resources.

The GT approach associates groups and communities with a traditionally recognised land area, aiding these communities in building skill levels and developing local institutions for the implementation of sustainable management plans[25]. Lund[26] confirms this when he notes that gestion de terroirs promises to integrate the social and physical environment, from a village perspective. Hence, one of the major differences between GT and SLA is that GT focuses on the terroirs and SLA focuses on the people themselves and is as such not limited to particular geographical spaces. At the same time, the gestion de terroirs approach simultaneously uses local empowerment and capacity building to respond to the immediate socio-economic needs of the local population as well as the long term problems of sustainable land and natural resource management, a feature it shares with SLAs. The gestion de terroirs approach can thus be defined as including some mixture of the following elements:

Community-based natural resource management

The empowerment of local communities

Increasing local capacity, through training and education

Stakeholder involvement - again leading to the empowerment of the community

Flexibility and adaptability of both projects and funding - this is something which goes against the raison d’être of most funding agencies!

Facilitating resource conflict resolution - through mutual management of resources

Participatory appraisal - on-going assessment and feedback in the hope of preventative action and trouble-shooting

Identifying local priority concerns (through involving them in processes of planning and development as well as in outcomes). Within this is the incorporation of local tacit knowledge in planning and development.

Decision-making by the local community - having an active part in testing new systems, identifying problems, researching solutions.

In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) people-centred approaches has been adopted over the past fifty years, but rarely they have been part of agricultural sectoral or macro policies. In most of the cases they have emerged alongside with social strategies. Following there is a brief presentation on the main PCA approaches applied in LAC since the 50’s.

(a) 1950s to 1970s:

The import substitution industrialization (ISI) model, which was implemented throughout much of the region during the post-war period until the early 1980s, promoted the shift from agriculture to industry. In the 70’s was promoted the Green Revolution which had the purpose to eliminate hunger by improving crop performance and to increase yields by using new crop cultivars, irrigation, fertilizers, pesticides and mechanization. The 1970s was a period of large scale development projects generated from centralised sources; the emphasis was on integrated development packages. While such programs resulted in significant increases in GNP in some countries, it also resulted in wider gaps between the rich and the poor.

Most development approaches adopted during this period involved a passive role of the majority of the people concerned whose “participation” was limited to adoption of the new technology. By the late 70s, it was evident that the top-down approaches were not delivering the results they claimed they would.

Some people-centred approaches were applied in this period, such as communal development, communal irrigation development, primary health care and nutrition, marketing cooperatives and social forestry. Communication for development was promoted in the 70’s as well as the integrated rural development approach.

Regarding the approaches to support rural women: (i) from 1950 to 1970, women were considered passive beneficiaries of development with interventions to support their reproductive roles, (ii) from 1975 to 1985 (Decade on Women), it was promoted the Women in Development approach (WID). Women were seen as active participants of development and there were support to small projects for women and measures to increase their productivity.

b) 1980’s and early 1990’s:

In the late 1970s and early 1980s there was a growing awareness that the problems in development were not simply technological but were also social, political and economic, and that these could be addressed by using some people-centred approaches. Equity and participation reasserted themselves as basic principles in development programs. Thus, there appears to be widespread agreement on the significance of people's participation in attaining development objectives.

Several international agencies have issued mandates for popular participation in their development programs. From these awareness and development skills emerged new methodologies and approaches such as rapid rural appraisal (RRA), participatory rural appraisal (PRA) methods, farming systems, and community-based resource management. Most of them applied in LAC. Participatory and action research, and communication for development were promoted as well.

Integrated rural development (IRD) became more popular and was widely used in LAC. Despite the acknowledgment of its limitations, such as insufficient participation of the beneficiaries and limited connection of these programmes to national policies, many international organizations and national governments supported this approach. In the case of Colombia, IRD became an agricultural strategy since mid 70s.

Regarding, the approaches to support the advancement of rural women, it was applied WID (Women in Development), more focused on strategic gender needs, and in this period it was also applied GAD (Gender and Development), which starts promoting gender equality and empowerment of women.

c) 1990s-2000:

The reforms in the nineties, in general, had a negative impact on agricultural performance as an outcome of the elimination of subsidies, credit and technological support services. On the other hand, the dynamics of economic growth are largely to be found within the sectors of commercial farmers who have been able to establish linkages with foreign, mostly transnational, capital, thereby integrating themselves in domestic and international agribusiness complexes.

The early optimism about the options for small farmers and peasants to modernize through contract farming for agribusiness has not been sufficiently justified in practice. Furthermore, there are indications that the gap (in levels of technology, productivity and income) between the commercial and entrepreneurial farmers and the “small farmers” has grown larger than ever. Economic policies directed toward modernizing the latter group are largely absent, as are social policies to mitigate the costs of economic adjustment in view of continuing high levels of rural poverty.

During this period there was an increasing awareness on the importance of natural resources and environment. There was progress in some legal reforms to promote access to, rationale use of and decentralized management of natural resources, and in addition, indigenous groups started receiving more attention and recognition of their rights (including territories).

In this period people-centred approaches were applied, such as sustainable livelihood-type, IRD (e.g. some programmes funded by IDB), territorial-based interventions, demand-driven participatory methodologies (i.e. IFAD, FAO), participatory and action research, communication for development, community-based natural resources management (i.e. forestry, watershed management).

Gender and development (GAD) was still promoted and some agencies started talking about gender mainstreaming. Although up to now, there are few achievements regarding the status of rural women and there is still a gap between purposes and reality.

Over the last ten years some international agencies and national governments have started reflecting on the need to formulate a new people-centred approach, considering the experience and the results of the different approaches applied in the region. Although until now there is not a new structured framework and underlined principles, some ideas are emerging related to a territorial based approach for development.

There are some common elements proposed by some international agencies based in LAC and national governments, similar to the ones proposed by SLA. The common elements that can be a base to design key principles for a new PCA for rural development in LAC are: people-centred, territorial based, decentralization and capacity building, multisectoral economy, competitiveness and efficiency, multi-level, links rural-urban, and the consideration of cross-sectoral issues (gender for example).

In this section, there will be a brief overview of the approaches, both inside and outside the FAO, which may be of interest as regards the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach to rural development and poverty alleviation. Each of these approaches have some degree of similarity to the SL approach and its framework, and, as most have been used in the field, may provide some valuable lessons for the SLA. So as to clearly and concisely explain these approaches, this chapter has been divided into two sections - the non-FAO approaches and FAO approaches.

(i) Non-FAO Approaches

These are approaches that may have some principles or ideas in common with the SL approach, and that may provide some useful lessons for SL. The approaches addressed in this section are not used in the FAO to any great extent, if at all, and have been developed by other agencies. Included in this are community-driven development, the rights-based approach, regional rural development and holistic management.

Community-Driven Development (CDD)

CDD is a relatively new approach to rural development, currently being used predominantly by the World Bank. A central feature of the approach is its attempt to place the community at the heart of the development process. The main principles of CDD are:

1. To place control and resources in the hands of the community

2. To view poor people as themselves assets and partners in development

3. To build-on existing institutions

The process of focusing on the community and its role in development leads to an emphasis being placed upon local empowerment and capacity-building within the community. CDD could perhaps be helpful for the sustainable livelihoods approach currently being developed by the FAO and DfID, in that it may illustrate the practicalities of attaining local empowerment and involvement in rural development in the field.

Rights-Based Approach (RBA)

The RBA can, to some extent, be regarded as coming from the development of the SL approach. As its central tenet, RBA sees social empowerment as of the greatest importance in rural development and poverty alleviation. According to CARE, who are among the leading developers of the approach, a “rights-based approach deliberately and explicitly focuses on people achieving the minimum conditions for living with dignity... by exposing the roots of vulnerability and marginalisation”[27]. Thus, the main principles of RBA are:

1. Participatory governance

2. Promoting inclusive development

3. Mutual accountability in respect of rights and responsibilities

4. A holistic perspective focusing on removing constraints and creating opportunities for livelihoods improvement

The approach may be particularly useful as regards the SL approach, in terms of the Policies, Institutions, and Processes (PIPs) box. It may give us some idea as to how the addition of “political capital” to the SL framework may be conceived.

Regional Rural Development (RRD)

With this GTZ-developed approach, the regional, or sub-national, context is taken as the primary level of intervention. Thus, this is a regional, rural and people-centred approach to poverty alleviation. The focus of RRD is:

1. The identification of new and better opportunities for rural development

2. Capacity-building for service identities

3. Capacity building for people, especially marginalized, so they can use services and opportunities

Thus, RRD is aiming for the lasting improvement of living conditions in rural regions, especially for poorer population groups. The four core principles of the approach are:

1. Democratisation

2. Partnership between government and communities

3. Joint knowledge generation

4. Gender equity and consciously interacting with marginalized groups.

Similarly to the RBAs, RRD may be interesting for the SL approach in terms of the PIPs box, and of “political capital” as a new asset in the framework.

The Holistic Management Model

The ideas underlying holistic management is a focus on a holistic goal for development, a goal developed “by those responsible for managing it, and expressing their collective needs and aspirations, both short-term and long-term”[28]. It thus consists of three parts:

1. Quality of life

2. Forms of production

3. Future resource base

In other words, the aim is not only to look at rural development from a holistic perspective, as is also the case with the SL approach, but to do so through the participation of the local people, through stakeholder consultation. The focus in this approach is on the ecosystems at local level, and on their sustainability within the process of development. As such, holistic management takes a far more environmentally-centred view of rural development than the other approaches mentioned here. In this case, it would be interesting to see how it is that the holistic perspective is carried through at the level of projects in the field.

(ii) FAO Approaches and/or Programmes

This section covers approaches to rural development that are currently in use in some form in the FAO, and which may also be relevant for the SL approach. This list includes integrated pest management, the code of conduct for responsible fisheries, the sustainable fisheries livelihoods program, FIVIMS, participation, nutrition, SEAGA, investment centre approaches, and community-based natural resource management.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

IPM is an approach to pest management, primarily, that began in Indonesia in the 1980s and is currently promoted by the FAO all over the world. “Integrated Pest Management” is a pest management system that in the socio-economic context of farming systems, the associated environment and the population dynamics of the pest species, utilises all available techniques in as compatible a manner as possible”[29]. A central feature of IPM is the setting-up of Farmer Field Schools (FFSs), which enable the true participation of local farmers in decision-making in the development process. It leads by empowering local farmers, allowing them to truly become partners in the development process, thus making it socially sustainable through stakeholder ownership. IPM pursues these multiple objectives:

Farmer empowerment

Conservation of biodiversity

Food security

Community education

Protection of human health

Policy reform

FFSs can be an interesting subject matter for the SL approach and its technique for local empowerment could inform the implementation of SL-rooted projects in the field.

Food Insecurity and Vulnerability Information and Mapping Systems (FIVIMS)

FIVIMS can be said to be any systems that assemble, analyse and disseminate information on who the food insecure are, where they are located and why they are food insecure, nutritionally vulnerable, or at risk. FIVIMS is a framework in which a wide range of activities may be carried out at both national and international levels. Thus, FIVIMS aim to[30]:

1. Raise awareness about food insecurity issues

2. Improve the quality of food insecurity data and analysis

3. Facilitate integration of complementary information

4. Promote better understanding of users’ needs and better use of information

5. Improve access to information through networking and sharing

Thus, FIVIMS may be a useful source of normative data in terms of planning target communities and populations for poverty alleviation and rural development.

SEAGA

The Socio-Economic and Gender Analysis Programme (SEAGA) is aimed at incorporating gender considerations into development projects, programmes and policies in order to make sure that all development efforts address the needs and priorities of both men and women. It provides development workers with methods and tools for conducting socio-economic and gender analysis and for strengthening people's capacity to incorporate gender issues in development.

SEAGA was established in 1993 to promote gender awareness when meeting development challenges. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Labour Organization (ILO) the World Bank and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) initially undertook the development of the SEAGA materials. From 1995, FAO is the lead agency in developing this Programme in collaboration with a number of other international and national agencies.

SEAGA’s guiding principles are:

Gender roles and relations are of key importance.

Disadvantaged people should be a priority in development initiatives.

Participation of local people is essential for sustainable development.

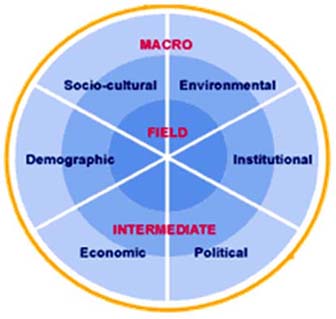

In terms of approach, SEAGA emphasizes the socio-cultural, economic, demographic, political, institutional and environmental factors that affect the outcome of development initiatives and the linkages between them from a gender perspective. Furthermore, SEAGA examines the linkages among these factors at three levels - macro (programmes and policies), intermediate (institutions) and field (communities, households and individuals).

Through this holistic vision of development, SEAGA provides an approach that seeks to:

Understand gender roles and relations,

Understand the socio-economic factors that affect development,

Account for and support disadvantaged people,

Ensure the active participation of all stakeholders,

Identify the linkages among different stakeholder groups,

Use bottom-up approaches to prioritise development initiatives,

Promote a participatory process in planning and implementing development activities and policies,

Facilitate network building among development workers and encourage the exchange of views and experiences.

The programme promotes an approach to development that is based on analysis of the socio-economic patterns affecting development projects and programmes and on the participatory identification of women's and men's development priorities. The analytical framework emphasizes the economic, social, institutional, political, environmental and demographic issues, and analyses the linkages among them from a gender perspective. The analysis targets three levels: field agents, development planners and policy- and decision-makers. For each of these audiences, it provides training and support through workshops, publications and ongoing collaboration.

The activities of SEAGA focus on increasing awareness of gender issues, as well as strengthening people’s capacity to incorporate gender considerations into development interventions. The SEAGA programme works to achieve its aim by:

Carrying out training workshops in socio-economic and gender analysis and gender awareness sessions,

Conducting technical workshops that apply socio-economic and gender analysis to specific issues,

Developing technical guides and handbooks that facilitate training in and dissemination of socio-economic and gender analysis,

Assisting nations in formulating national plans of action to incorporate gender issues in policies,

Collaborating with development organisations and institutions in their endeavours,

Creating a network of specialists to share ideas and experiences,

Releasing a newsletter that promotes the exchange of information amongst development specialists.

Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBRNM)

The Community-Based Natural Resources Management approach (CBNRM) is people-centred, community-oriented and resource-based. It starts from the basic premise that people have the innate capacity to understand and act on their own problems. It begins where the people are i.e. what the people already know, and build on this knowledge to develop further their knowledge and create a new consciousness. It strives for more active people's participation in the planning, implementation and evaluation of natural resource management programs. It involves an iterative process where the community takes responsibility for the assessment and monitoring of environmental conditions and resources and the enforcement of agreements and laws. Since the community is involved in the formulation and implementation of management measures a higher degree of acceptability and compliance can be expected. CBNRM allows each community to develop a management strategy which meets its own particular needs and conditions, thus enabling greater degree of flexibility and modification.

|

[19] Ashley, C. and Carney,

D. (1999), “Sustainable Livelihoods: Lessons From Early Experience”

(DfID), p.1 [20] Dixon, J., Gulliver, A., Gibbon, D. (2001), “Farming Systems and Poverty”, FAO [21] from Collinson 2000: 300, paraphrased and updated from Byrnes 1990 [22] Ellis and Biggs 2001. Evolving themes in rural development. Development Policy Review 19 (4), pp. 437-448 [23] Toulmin, C. (1994) Gestion de Terroirs: Concept and Development [24] Bouttier, N. (1996) Décentralisation et Développement Locale [25] World Bank (1998) West Africa: Community Based Natural Resource Management [26] Lund, C. (2000) African Land Tenure: Questioning Basic Assumptions [27] CARE Workshop in Atlanta, August 2002, “A Rights-Based Approach to Achieving Household Livelihoods Security” from Drinkwater, M. (2001), “Programming Principles for a Rights-Based Approach” [28] Savory, A. “Elements Within the Holistic Management Model”, from http://www.holisticmanagement.org/ahm_orig.cfm? [29] Dent, D.R. (1995) “Integrated Pest Management”, Chapman and Hall, London, p.356 [30] Taken from the FIVIMS Inter-Agency Website at: http://www.fivims.net/static.jspx?lang=en&page=fivims |