High seas resources

High seas resources are those resources which exist beyond national jurisdiction. They include species which are distributed essentially beyond 200 miles although these species may spend part of their life cycle in the coastal areas for reproduction or feeding. They also include portions of EEZ stocks which extend beyond 200 miles (referred to as straddling stocks) and species which undertake extensive migrations between the EEZs and high seas, across oceans and/or across many EEZs. The extension of their distribution and the mobility of the fleets exploiting them have a direct bearing on the type of management arrangement which will be adequate to ensure sustainability (e.g., local, regional, ocean-wide or even global).

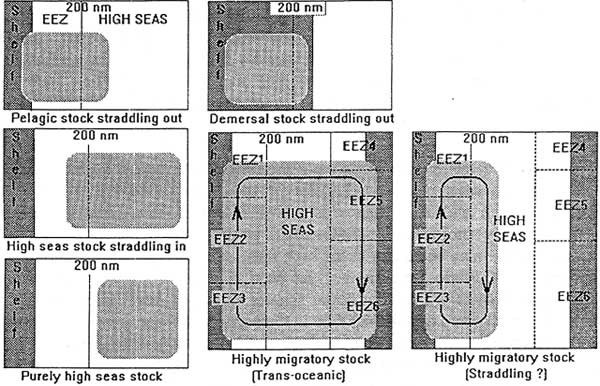

In biological terms and depending on the closeness of their relationships with the bottom, high seas resources can be neritic or oceanic with a range of intermediate categories (Figs. 1 and 2). High seas neritic resources have their life cycle and distribution largely confined to the continental shelf and upper slope despite the fact that they extend to and may be caught in the high seas. Neritic high seas resources will be found where a 200-mile zone has not yet been claimed (e.g., off China or in the Mediterranean Sea) or where continental shelves extend beyond 200 miles (as on the North Pacific shelf or on the Flemish Cap in the Northwest Atlantic). Neritic resources can be demersal (i.e., having strong relations with and dependence on the bottom) or pelagic (i.e., living in the upper layers of the ocean and having little contact with the bottom). Demersal high seas resources include mostly straddling stocks and a few strictly high seas stocks on seamounts.

Figure 1 Illustration of the terminology used in the text

Figure 2 Types of high seas resources (from a biological point of view)

High seas oceanic resources are distributed and caught mainly beyond the outer shelf and/or migrate extensively across the open ocean even though they may pass a key stage of their life cycle close inshore and yield large catches inside the EEZs. These resources are essentially pelagic for most of their life cycle but some demersal resources exist on seamounts. A glance at the FAO SPECIESDAB (Global Species Database for Fishery Purposes) indicates that close to 400 species can be considered purely or significantly oceanic (Garcia and Majkowski, 1992). There are about 50 species of cephalopods, 40 species of sharks, 60 species of marine mammals and 230 fish species. The biological information available on these species and their present potential and status is generally poor, except perhaps for some whales and large tunas and their management and conservation are a matter of concern. Most oceanic high seas resources are dispersed, difficult to harvest economically and extremely difficult to study with the required accuracy. They are usually exploited by long-range fleets operating in areas where target species concentrate for feeding or reproduction. Average densities available in the high seas are much lower than in upwelling areas and coastal zones. Biomass of plankton, mesopelagic fish, krill and small prey fish species are accumulated in hydrographic structures and critical areas where predators (oceanic jacks, some gadoids, squid, tunas, seals, whales, dolphins, sharks, etc.) are economically available. The increasing scarcity of coastal resources due to overfishing in EEZs is an incentive to increase pressure on these areas and on the often fragile species which inhabit them.

Highly migratory species

Highly migratory species are referred to in Article 64 of the 1982 Convention which provides for the rights and obligations of coastal and other States whose nationals fish for these species. A list of species considered highly migratory at the time of elaboration of the Convention was attached to the agreement (see Annex 1). No operational definition of “highly migratory” has been given (see also Fig. 2).

Article 64 reflects the view that the management of highly migratory species requires cooperation between the coastal State and other States fishing for the resource. A trend is developing in which fishing agreements are signed between coastal and distant-water fishing nations (DWFNs) through which the DWFNs accept to pay for the access to tunas in the EEZs and where the coastal State unilaterally fixes (or negotiates) the quotas or the number of licences (e.g., in the South Pacific area, Seychelles, Mauritius, Morocco, Senegal, etc.). This trend has sometimes been taken as implying de facto a privileged right for the coastal State (Munro, 1993). The list of highly migratory species given in the Convention includes species with wide geographic distribution, both inside and outside the 200-mile zone and within which they undertake migrations of variable distances. They are pelagic species, and often have neritic and oceanic phases in their life cycle. The list includes 11 tuna, 12 billfish species, pomfrets, 4 species of sauries, dolphinfish (Coryphaena spp.), oceanic sharks and cetaceans (both small and large). Mammals are treated separately (Article 65) and will not be considered further here. It is important to note that there are species undertaking large-scale migrations which have not been included in this list.

For example, Euthynnus lineatus, that is probably more oceanic than the other two Euthynnus species, is not included. Other three tuna-like species (Acanthocybium solandri, Allothunnus fallai, and Gasterochisma melampus) classified as oceanic in the FAO SPECIESDAB are not included in the list. Many other tuna-like species migrate long distances while remaining close to the continent, and may be considered as highly migratory or straddling. In addition, some scientific names have changed in the meantime and the list, as it presently stands, is not satisfactory from a scientific point of view.

The total catches identified and reported to FAO on species and groups of species listed in the Annex I of the 1982 Convention have increased from 1.7 million t in 1970 to 4.3 million t in 1991 (Figure 3 and Table 2).

Figure 3: Catches of Highly Migratory Species and Straddling Stocks (source: FIDI, FAO)

| Species | 1991 Catches in t |

|---|---|

| Albacore | 168 797 |

| Northern bluefin tuna | 30 182 |

| Bigeye tuna | 238 353 |

| Skipjack tuna | 1 556 732 |

| Yellowfin tuna | 1 011 764 |

| Blackfin tuna | 2 107 |

| Atlantic black skipjack | 20 787 |

| Kawakawa | 156 312 |

| Southern bluefin tuna | 12 398 |

| Frigate and bullet tunas | 206 099 |

| Pomfrets | 168 853 |

| Marlins | 48 228 |

| Sailfishes | 7 364 |

| Swordfish | 67 142 |

| Other billfish | 57 777 |

| Sauries | 402 210 |

| Dolphinfish | 37 062 |

| Oceanic sharks | 62 386 |

| Total | 4 254 553 |

Straddling stocks

The 1982 Convention does not use the term “straddling” stocks, instead it refers in Article 63.2 to a “stock or stocks of associated species occurring both within the exclusive economic zone and in an area beyond and adjacent to the zone”. A case not foreseen explicitly by the Convention, however, is that of a stock occurring within the EEZs of two or more coastal States and the adjacent high seas3. As the straddling nature of a stock is a local (geographic) peculiarity related mostly to the shelf width, straddling stocks must be referred to not only by their species name (like the highly migratory species) but also by their specific location (e.g., Grand Banks cod). In most cases the limit of this jurisdiction is 200 miles but there are still areas where EEZ claims have not yet been made (e.g., in the Mediterranean). The degree to which a stock “straddles” usually depends on the extension of the shelf beyond the limit of the national jurisdiction and its seasonal availability thereof. Straddling stocks can be demersal or pelagic and, depending on the shelf width, they can be neritic or oceanic.

3 In this paper both types of stocks are considered as straddling

The usual understanding seems to be that straddling stocks are mainly EEZ “residents” (i.e., their overall biomass is largely in the EEZ) which straddle “out” in the high seas a few miles and perhaps only seasonally (Fig. 2). The “adjacency” required implies probably that there should be some geographic continuity between the EEZ and straddling portions of the stock. It is important to understand that when a shelf extends beyond 200 miles, it is the whole species assemblage which is straddling and not merely the target species.

In addition, some stocks could be mainly “high seas residents” (i.e., their overall biomass is largely outside the EEZs) which straddle “in” the EEZs (Fig. 2). Most of the species occurring in the high seas are found inside and outside the 200-mile limit, either at the same time or sequentially (e.g., during the various phases of their life cycle) and could be considered “straddling”, at least from a purely biological point of view. This is particularly important for small island countries which have a tiny piece of shelf (the reef and lagoon) in the middle of an immense oceanic ecosystem. Their reef resources are purely national but their oceanic resources, which represent a very large proportion of the marine resources available to them for development, are straddling or highly migratory. This particular situation renders the small island resources very vulnerable to high seas fishing and probably underlies the particularly deep concern of these countries towards uncontrolled high seas fishing. Whether or not their oceanic resources can be called straddling in legal terms, they are straddling in biological terms and merit the same type of coordinated management.

The biological distinction between the straddling and highly migratory species is not always straightforward. The Chilean horse mackerel, for instance, which straddles about 1 500 miles off the EEZs of Chile and Peru is a particular case of straddling stock which might, from the biological standpoint, be as “highly migratory” as some of the smaller tunas mentioned in the 1982 Convention. It has already been mentioned that some of these small tropical tuna species have limited migrations outside the EEZs, particularly when their lifespan is significantly reduced by fishing.

The number of straddling stocks is largely underestimated by the following factors:

if they are not exploited (particularly by foreign fleets in the adjacent high seas) there is no conflict of interests and they do not attract international attention;

only the target species tends to be mentioned when in reality the whole species assemblage is straddling4, and all the related by-catch species should also be included in any management plan.

4 Article 63.2 refers to “stocks of associated species”

The management issues related to straddling stocks depend on their biological characteristics and, in particular, on the degree of mixing between the EEZ and high seas compartments of the stock (Fig. 4). In instances where mixing is considerable (probably in most cases) because of random dispersion, ontogenic or seasonal migrations, the stock should be managed as one single unit, and management measures must be harmonized over the entire range of distribution of the stock.

Sedentary stocks with no movement and no mixing

Resource may be fixed [coral] or buried [clams]. Each compartment may be managed separately but depletion of spawners in one compartment may affect the other.

Low diffusion stock, little movement and little mixing

Stock compartments could be managed separately with little error. Depletion of spawning stock in one compartment may affect reproduction in the other.

High diffusion stock. Extensive random Movements and important mixing

Stocks should be managed as one unit. Management needs to be identical on both sides. Mismanagement of one of the compartments will directly affect the other

Inshore-offshore ontogenic migrations

The stock should be managed as one single unit. Specific measures [quotas, mesh size, effort controls] may be area-specific. Age-specific fisheries should be managed as sequential fisheries.

Sequential fisheries

Seasonally migrating stock

The stock should be managed as a single unit. Seasonal patters need to be taken into account.

Figure 4: Different types of straddling stocks

It is extremely difficult, considering the deficiency in the data related to straddling stocks, to assess the real economic dimension of the straddling stock problem (at least in terms of reported landings). In order to provide a very crude order of magnitude, and following the analysis given below area by area, the reported landings of the species known as “straddling” or “likely to straddle” have been calculated. The figures (Tables 3 and 4) should be regarded with extreme caution. There is no reliable information in this respect and there will not be any until such time that a proper reporting/collecting system is set in place. The total catches (in EEZs and adjacent high seas) have evolved from 5.8 million t in 1970 to 12.4 million t in 1991, after a peak of 13.7 million t in 1988–89 (Fig. 3). In 1991, the total catches were about 11.4 million t of demersal fish and squids and 1 million t of tuna and tuna-like species including highly migratory species (Table 3).

| Statistical Division (Ocean region) | Tuna-like species | Other species | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 (N.W. Atlantic) | 0.9 | 739.1 | 740.0 |

| 27 (N.E. Atlantic) | 0.3 | 437.0 | 437.3 |

| 31 (W.C. Atlantic) | 30.6 | 0 | 30.6 |

| 34 (E.C. Atlantic) | 7.2 | 0 | 7.2 |

| 37 (Mediterranean) | 97.5 | 58.4 | 155.9 |

| 41 (S.W. Atlantic) | 3.0 | 782.5 | 785.5 |

| 47 (S.E. Atlantic) | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 51 (W. Indian) | 86.7 | 0 | 86.7 |

| 57 (E. Indian) | 44.2 | 0 | 44.2 |

| 61 (N.W. Pacific) | 281.0 | 3 905.6 | 4 186.6 |

| 67 (N.E. Pacific) | 0 | 1 372.2 | 1 372.2 |

| 71 (W.C. Pacific) | 239.4 | 0 | 239.4 |

| 77 (E.C. Pacific) | 246.2 | 5.8 | 252.0 |

| 81 (S.W. Pacific) | 1.2 | 90.1 | 91.3 |

| 87 (S.E. Pacific) | 26.9 | 4 017.6 | 4 044.5 |

| Total | 1 065.6 | 11 408.3 | 12 473.9 |

It appears from these figures that the Northwest and Southeast Pacific areas are the most important sources of straddling stocks (mainly demersal) followed by the Northeast Pacific and the Southwest Atlantic.

| Species | Tuna-like | Other species |

|---|---|---|

| American plaice (Long rough dab) | 51 342 | |

| Atlantic bonito | 85 | |

| Atlantic cod | 422 625 | |

| Atlantic halibut | 3 544 | |

| Atlantic Spanish mackerel | 538 | |

| Greenland halibut | 69 181 | |

| Illex illecebrosus | 15 743 | |

| King mackerel | 328 | |

| Longfin squid | 19 564 | |

| Silver hake | 105 973 + 23 000 | |

| Witch flounder | 15 152 | |

| Yellowtail flounder | 20 250 | |

| TOTAL N.W. ATLANTIC (Area 21) | 951 | 746 374 |

| Atlantic bonito | 305 | |

| Blue whiting (= Poutassou) | 433 745 | |

| Illex illecebrosus | 3 226 | |

| TOTAL N.E. ATLANTIC (Area 27) | 305 | 436 971 |

| Atlantic bonito | 2 399 | |

| Atlantic Spanish mackerel | 19 359 | |

| Cero | 231 | |

| Flyingfishes nei | 1 568 | |

| Illex illecebrosus | 4 | |

| King mackerel | 5 565 | |

| Seerfishes nei | 726 | |

| Wahoo | 774 | |

| TOTAL W.C. ATLANTIC (Area 31) | 30 622 | 4 |

| Atlantic bonito | 1 918 | |

| Flyingfishes nei | 457 | |

| Plain bonito | 399 | |

| Wahoo | 645 | |

| West African Spanish mackerel | 3 795 | |

| TOTAL C.E. ATLANTIC (Area 34) | 7 214 | 0 |

| Atlantic bonito | 25 997 | |

| Atlantic horse mackerel | 10 083 | |

| Atlantic mackerel | 7 220 | |

| Blue whiting (=Poutassou) | 11 626 | |

| European hake | 39 047 | |

| Jack and horse mackerels nei | 22 114 | |

| Mediterranean horse mackerel | 32 081 | |

| Plain bonito | 9 | |

| Todarodes sagittatus sagittatus | 7 775 | |

| TOTAL MEDITERRANEAN (Area 37) | 97 504 | 58 448 |

| Salilota australis | 57 | |

| Antarctic rockcods, noties nei | 3 | |

| Argentine hake | 521 312 | |

| Atlantic bonito | 1 887 | |

| Atlantic Spanish mackerel | 26 | |

| Blue jack mackerel | 316 | |

| Flyingfishes nei | 664 | |

| Grenadiers | 14 858 | |

| Illex argentinus | 77 428 | |

| King mackerel | 67 | |

| Patagonian grenadier | 9 686 | |

| Patagonian hake | 1 944 | |

| Patagonian toothfish | 2 232 | |

| Sevenstar flying squid | 3 | |

| Southern blue whiting | 154 941 | |

| TOTAL S.W. ATLANTIC (Area 41) | 2 960 | 782 464 |

| Atlantic bonito | 473 | |

| Wahoo | 12 | |

| West African Spanish mackerel | ||

| TOTAL S.E. ATLANTIC (Area 47) | 485 | 0 |

| Flyingfishes nei | 90 | |

| Indo-Pacific king mackerel | 9 483 | |

| Lanternfishes | 2 210 | |

| Longtail tuna | 29 414 | |

| Narrow-barred Spanish mackerel | 32 447 | |

| Seerfishes nei | 12 673 | |

| Streaked seerfish | 372 | |

| Wahoo | 1 | |

| TOTAL W. INDIAN (Area 51) | 86 690 | 0 |

| Flyingfishes nei | 2 039 | |

| Indo-Pacific king mackerel | 14 360 | |

| Longtail tuna | 1 080 | |

| Narrow-barred Spanish mackerel | 13 697 | |

| Seerfishes nei | 12 181 | |

| Streaked seerfish | 850 | |

| Wahoo | ||

| TOTAL E. INDIAN (Area 57) | 44 207 | 0 |

| Alaska (Walleye) pollock | 3 521 306 | |

| Flyingfishes nei | 620 | |

| Indo-Pacific king mackerel | 627 | |

| Japanese flyingfish | 6 328 | |

| Japanese Spanish mackerel | 247 855 | |

| Longtail tuna | 17 370 | |

| Seerfishes nei | 8 212 | |

| Todarodes pacificus | 384 310 | |

| TOTAL N.W. PACIFIC (Area 61) | 281 012 | 3 905 616 |

| Alaska (Walleye) pollock | 1 372 187 | |

| TOTAL N.E. PACIFIC (Area 67) | 1 372 187 | |

| Flyingfishes nei | 32 432 | |

| Indo-Pacific king mackerel | 7 950 | |

| Japanese Spanish mackerel | 1 427 | |

| Longtail tuna | 115 293 | |

| Narrow-barred Spanish mackerel | 60 385 | |

| Seerfishes nei | 21 399 | |

| Wahoo | 537 | |

| TOTAL W.C. PACIFIC (Area 71) | 239 423 | 0 |

| Eastern Pacific bonito | 1 315 | |

| Flyingfishes nei | 44 | |

| Jumbo flying squid | 5 846 | |

| Pacific sierra | 5 404 | |

| Seerfishes nei | 2 | |

| TOTAL E.C. PACIFIC (Area 77) | 246 188 | 5 846 |

| Longtail tuna | ||

| Narrow-barred Spanish mackerel | 20 | |

| Orange roughy | 69 440 | |

| Oreo dories | 20 646 | |

| Seerfishes nei | 1 137 | |

| TOTAL S.W. PACIFIC (Area 81) | 1 157 | 90 086 |

| Chilean jack mackerel | 3 852 928 | |

| Eastern Pacific bonito | 25 357 | |

| Flyingfishes nei | 85 | |

| Pacific sierra | 1 473 | |

| Patagonian grenadier | 164 679 | |

| TOTAL S.E. PACIFIC (Area 87) | 26 915 | 4 017 607 |

| WORLD TOTAL | 1 065 636 | 11 415 600 |

The next two sections cover respectively highly migratory species and straddling stocks. The section on highly migratory species discusses not only the species listed in the 1982 Convention (such as tunas, billfish, marlins, oceanic sharks, marine turtles, pomfrets, dolphinfish and sauries) but other species of actual or potential importance to high seas fisheries with similar biological characteristics (such as tuna-like species, squids, oceanic horse mackerel, etc., of which very little is known). For each of these groups, whenever possible, the resources, the fisheries and the present status of stocks will be described. The following high seas resources are not reviewed here:

Marine mammals, because the issue is too complex to be properly dealt with in detail;

Antarctic resources;

Mesopelagic resources which could be straddling in some areas but which, at this moment, are neither economically important nor a source of international conflict;

Salmon which, as an anadromous species, is treated under a different article of the 1982 Convention (Article 66).