by

William M. Ciesla

Forest Protection Officer

Forest Resources Division

FAO, Rome, Italy

Brief case histories of recent introductions of forest pests are presented. Included is the introduction of Asian gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar, into Europe and North America; the European bark beetle, Tomicus piniperda, into the United States, the pine scales, Hemiberlesia pityophila and Oracella acuta into China, the oriental scale, Aonidiella orientalis. into West Africa and leucaena psyllid, Heteropsylla Cubana, into Africa. Factors which cause the introduction and establishment of new forests pests are discussed as are methods of prevention and control. FAO assistance to member countries in the integrated pest management of both native and introduced forest pest is reviewed.

* * * * *

I want to take this opportunity to add my welcome on behalf of FAO to the participants of this workshop on leucaena psyllid. This is the second workshop of this type that I have the pleasure of being involved in for eastern and southern Africa. The first was held in 1991 in Mugaga, Kenya and focused on introduced conifer aphids, especially the cypress aphid, Cinara cupressi, which continues to cause widespread losses throughout the subregion. Consequently, I see the faces of many friends in the audience. I also see many new faces and am looking forward to getting acquainted with additional colleagues engaged in our area of common interest; the management of destructive forest pests. I also sense a great deal of enthusiasm among the members of the audience. This tells me that we are going to have an exciting and stimulating workshop.

Two years ago, I had the privilege of working with colleagues in Brazil to help organize a regional conference on another introduced forest pest; the European wood wasp, Sirex noctilio, which is now present in at least three South American countries. For this workshop, I prepared a worldwide overview of recent introductions of forest pests. Two versions of this overview are now published (Ciesla 1 993 a and b). Now, two years later, I find that there have been several additional introductions. In addition, my earlier search of the literature failed discover several case histories which I am now aware of. Therefore, rather than repeat material which has already been published, I want to review some additional case histories of recent pest introductions and describe briefly some activities that the FAO Forestry Department is currently engaged in to assist its member countries in managing these pests.

There are presently outbreaks of gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar, in several European countries including parts of Germany, Switzerland, France, the Slovak Republic and northern Austria. In Germany, infestations ranging from a few ha to over 30 000 ha were reported in 11 states in 1993 (Deutscher Bundestag 1993). Additional defoliation was anticipated for 1994. Contaminated shipping from ports in these countries presents a source of introductions of this insect to other parts of the world.

During July 1993, a military cargo vessel carrying US Army munitions from Germany docked in Wilmington, North Carolina, USA. When the hold of the ship was opened, large numbers of both male and female gypsy moths escaped. The presence of flying females indicates that the population of gypsy moths presently in outbreak status in Europe consists of, at least in part, the Asian form. There is also evidence that the Asian gypsy moth is hybridizing with local populations (Hofacker et al 1993). Efforts to eradicate populations in and around the port of Wilmington, North Carolina were conducted this year and will likely continue next year.

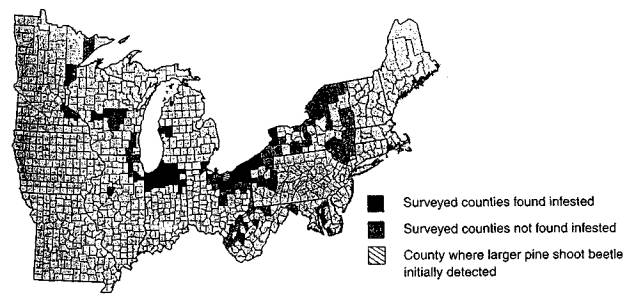

The European bark beetle, Tomicus piniperda, was discovered infesting pine plantations in the state of Ohio, USA in 1992. The insect has been found in Scots pine, Pinus sylvestris, which is widely planted in the central United States, and several native species including P. banksiana, P. resinosa and P. strobus. Surveys which have been conducted since its introduction, indicate that infestations are widespread and portions of three states; Indiana, Ohio and New York are involved (Fig 1). A quarantine on the movement of pine material from the infested areas has been imposed to help slow the spread of this insect (Miller-Weeks et al 1994).

During the early 1980's, a scale insect, Hemiberlesia pityophila, was accidentally introduced into Guangdong Province, in southeastern China. The insect was introduced from either Japan or Taiwan and caused widespread damage to both natural and planted forests of Pinus massoniana. With the assistance of FAO through its Technical Cooperation Programme (TCP) a parasitic wasp was introduced from Japan. This parasitoid was easily established and exerted a high degree of control.

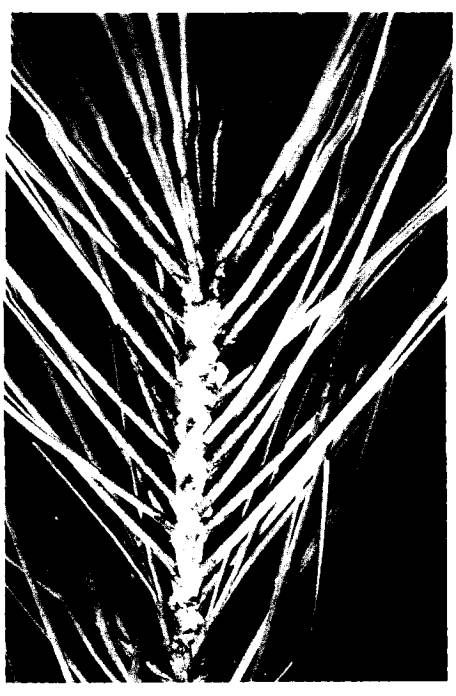

In 1988, another scale insect, Oracella acuta, which is native to the southeastern United States, was accidentally introduced into Guangdong Province on pine scion material collected in the USA to improve the quality of planting stock (Debarr 1992). The insect was discovered in 1990 when damage was detected in the Hongling Pine Seed Orchard near Taishan, where the scion material was grafted onto rootstocks. New shoots and cones are infested by colonies of scales (Fig 2). Damage causes deformity, growth loss and possible loss of seed. At the time of the insect's discovery, approximately 55 ha were infested. In the absence of the natural enemies which keep this insect under control in its native habitat, it spread rapidly and by the end of 1993, infested a gross area of approximately 136,000 ha. Infestations are now spreading at the rate of 1 7 to 22 km/yr. Most severe infestations are currently found in plantations of P. elliottii, however the

Figure 1 - Known distribution of the European bark beetle, Tomicus piniperda, in the central USA (Source: Miller Weeks et al 1994)

native P. massoniana, which covers large areas of China south of the Yangtze River, is also infested (Pan Wuyao n.d.). Infestations do not yet occur in the portion of Guangdong Province where extensive plantations of P. taeda have been established. This pine is the favourite host of O. acuta in the United States, and the scale is expected to spread into this area in the future. This insect posses an immediate threat to the future productivity of pine plantations in Guangdong Province in the short term and all of the China's pine forests south of the Yangtze River in the long term. Consequently it is considered a high priority pest problem by the Ministry of Forestry (MOF). Presently 20 entomologists representing various institutions in Guangdong Province have been assigned to develop a solution to the problem. In addition, a laboratory at the Heshan Forest Research Institute, which is located within the infested area, has been converted into a quarantine facility and partially equipped to receive, screen and mass rear parasitoids of O. acuta (Pan Wuyao n.d.).

Neem, Azadirachta indica, a tree native to the Indian subcontinent, has been widely planted throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. One of the major insect pests of neem is the oriental scale, Aonidiella orientalis (Fig 3). Also native to India, this insect first appeared in the Cameroon during the mid-1970's and has caused widespread damage to neem trees planted in the region including loss of foliage, branch dieback and tree mortality (Ciesla 1993c). Infestations were first detected in Nigeria in

Figure 2 - Pine scale, Oracella acuta, on Pinus taeda, Guangdong Province, China.

Figure 3 - Oriental scale, Aoinidiella orientalis on neem in Nigeria.

1987 along the border with the Cameroon where it is believed to have been initially introduced. The insect is now known to be present in varying degrees in at least seven states in Nigeria.

With the leucaena psyllid having gained a foothold on the African continent in 1992, infestations are spreading rapidly. Populations of this insect can now be found wherever leucaena occurs in Kenya and Tanzania. There are also reports of infestations in Burundi and Ethiopia. We will learn of the exact status of this insect in Africa when the individual country reports are presented at this workshop.

Pests and diseases are able to disperse into new habitats through a variety of means. Humans are important factors, either as direct vectors, through international trade or movement of plant materials. Introduction of exotic plants into new habitats, especially extensive areas of single species forest plantations, which provide a large volume of suitable host material, increases the probability of establishment if a new insect is introduced. Air currents, can also disperse insects into new habitats.

Throughout history, human societies have moved from place to place. As they moved about, they carried with them items of food, clothing or plant materials which harboured

pests and were subsequently introduced into new locations. Modern transportation systems make humans even more efficient vectors of insects. Travel times have been reduced. Therefore the probability of insects surviving a long distance journey has increased. In addition, today's transportation systems make it possible for more people to travel. Therefore, the number of potential human vectors has increased.

Occasionally insects are intentionally introduced into a new habitat. This was the ease with the initial introduction of gypsy moth into North America. A colony of insects was brought into Massachusettes, USA, by a French scientist for hybridization experiments with the domestic silkworm. A portion of the laboratory colony escaped and found the surrounding oak forest a suitable habitat for colonization. Once established, the insect was able to spread overland through dispersal of young larvae by air currents. Adult females depositing occasional egg masses on motor vehicles or cargo ships serve as a means of long distance spread (Doane and McManus 1981).

International trade in agriculture and forest products is another means by which pests are spread. As larger volumes of commodities are transported and new trade routes are opened, the probability of new insect introductions increases.

Logs and other wood products provide suitable habitat for bark beetles and wood borers. Unprocessed logs are an especially high risk commodity because the cambium layer is the breeding site for many pest species. Imported logs were the means by which the European wood wasp was introduced into New Zealand and the smaller European elm bark beetle, a vector of Dutch elm disease, Ophiostoma ulmi, was introduced into North America. Recently, the presence of the destructive North American bark beetle, Dendroctonus pseudotsugae, and several other wood boring insects was detected in logs imported into China (Ciesla 1992).

Wooden cargo crates and pallets are also a potential source of bark beetles and wood borers. These materials contain strips of bark which can support bark beetles or other cambium infesting insects. They were probably the means by which the European bark beetles H. ater, H. ligniperda and O. erosus, were introduced into Chile (Ciesla 1988) and the North American bark beetle, Ips grandicollis, was introduced into Australia (Morgan 1988).

Russian ships, containing large numbers of egg masses of the Asian form of the gypsy moth, calling at ports on the Pacific Coast of North America for grain, are believed to be the source of infestations detected in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, Tacoma, Washington and Portland, Oregon, USA (USDA 1992). Shipment of military supplies from Germany to the east coast of the USA resulted in still another introduction of Asian gypsy moth (Hofacker et al 1993).

Human introduction of plant materials for agriculture and forestry can increase the risk of pest introduction and establishment in two ways; through direct introduction of pests on the plant material being introduced, or by providing suitable host material for the establishment of subsequent pest introductions.

There are numerous examples of insects being introduced on tree seedlings or genetic material. The classic example is the introduction of white pine blister rust, Cronartium ribicola, into North America on white pine planting stock (Manion 1991). During the 1960's, Kenya was involved in a project aimed at improving the genetic quality of its pine plantations. Grafted Pinus caribea received from Australia was infested by a pine woolly aphid, Pineus sp. By the time the discovery was made, air currents had dispersed aphids to nearby pine plantations (Owuor 1991). The insect is now widely distributed in eastern and southern Africa. The pine scale, Oracella acuta, was introduced into China in a similar manner.

Extensive areas of forest plantations have been established throughout the world to help meet needs for fuel, wood product, fodder and of 1990, 90 countries in the tropics reported having a net area of 30.7 million ha of forest plantations (Forest Resources Assessment 1990 Project 1993). Many of these plantations consist of fast growing, exotic trees such as species of the genera Cupressus, Eucalyptus, Leucaena, Pinus and Populus. During the past three decades, the area of exotic forest plantings has increased dramatically. In 1955, there were 700 000 ha of eucalyptus plantations worldwide. By 1979, the area had increased to 4 000 000 ha in 58 countries (Jacobs 1979) and by the end of 1990, an estimated 10 million ha of eucalyptus plantings had been established in Africa, Asia and the Pacific and Latin America (Forest Resources Assessment 1990 Project 1993). There are an estimated 4.6 million ha of pine plantations, mostly exotics, in the tropics (Forest Resources Assessment 1990 Project 1993). In addition Chile and New Zealand each have approximately 1.1 million ha of Pinus radiata plantations. While many of these plantations had been relatively free of damaging pests for many years, recent introduction and establishment of insects such as Rhyacionia buoliana, Cinara cupressi and Phoracantha semipunctata are now making protection of these plantations from insect damage an important activity.

Insects can be transported for long distances by air currents. This is a key means of dispersal for both larvae and adults of many species. In eastern Canada, for example, large numbers of moths of spruce budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana (Clemens), have been dispersed for distances up to 600 km from their point of origin (Blais 1985).

The sudden, virtually simultaneous, appearance of leucaena psyllid, over large areas of Asia and the Pacific region has led to speculation that it may have been introduced by winds rather than via human vectors. Waterhouse and Norris (1987) suggest that in order for the insect to have spread over a very large area of the Pacific Ocean land masses in less than two years, it must have been carried on moving air masses. Napompeth (1990) discusses the seasonal collapse of populations in Thailand and the role of localized population pockets and typhoons from the South China Sea carrying insects to continental southeast Asia as sources of re-invasion.

Preventing accidental introduction is the first line of defense in managing exotic pests. Two lines of action can be taken; inspection of incoming logs, wood products and plant materials and internal quarantines.

MANAGEMENT OF IMPORTED FOREST AND PLANT PRODUCTS - Countries with extensive plantations of exotic trees and those which import large volumes of wood or plant products are especially susceptible to introduction and establishment of undesirable exotic insects. Risk of new introductions can be minimized through management of imported materials by:

Inspection of incoming materials at international ports of entry.

Restrictions on imports from high risk areas.

Proper treatment of infested plant materials and wood products.

These systems are implemented through passage of appropriate legislation, decrees or regulations; employment of trained inspectors who can recognize and intercept infested material and a capability for treating or disposing of infested material. In order to minimize the risk of new pest introductions, it is also necessary to also inspect wooden cargo crates, pallets, and scrap lumber in addition to plant materials, unprocessed logs and lumber.

When new trade routes for forest products or plant materials are planned, analysis of the risk of introduction of potentially damaging pests should be conducted. Such an analysis was conducted by USDA when several timber companies in the United States expressed an interest in importing logs from Siberia and the Russian Far East (USDA 1991).

Cooperation between trading partners to prevent introduction of potentially damaging forest insects is also desirable. This could involve the exporting country providing technical assistance and training to the importing country on how to detect, identify and treat potentially destructive insects or inspection and treatment of infested products before they are shipped.

INTERNAL QUARANTINES - When a new pest is detected and its distribution is determined, it may be necessary to regulate movement of plant materials and wood products to prevent spread. Internal quarantines, in conjunction with other pest management tactics, are being been used to confine Dendroctonus micans to its present area in the UK and to prevent the spread of isolated infestations of Lymantria dispar in the central and western United States.

Surveys designed to monitor the distribution and population density of an insect should be put in place as soon as a new insect is detected. These should be designed to detect low level populations in restricted areas. Available techniques include the use of traps baited with aggregating or sex pheromones, use of trap trees or systematic surveys in areas of high risk.

Eradication of a newly introduced insect is a viable option provided that the insect is detected shortly after it becomes established, is present in small numbers and its distribution is restricted to a relatively small area. Eradication projects often rely on the use of chemical pesticides. If a pest is introduced and established several times, as has been the case with gypsy moth in North America, repeated eradication projects must be undertaken. This has proven to be costly, hazardous and unacceptable to large segments of the public.

Use of environmentally friendly tactics, such as the bacterium, Bacillus thuringiensis, to eradicate localized infestations of gypsy moth, has helped to make eradication a more acceptable tactic.

Often, by the time an undesirable exotic forest pest is discovered, it is established, abundant and widespread. This is true even in developed countries as demonstrated by the wide distribution of the European bark beetle, Tomicus piniperda at the time of its discovery in the USA (Miller-Weeks et al 1994). Eradication is no longer a viable option. Under these circumstances, management of the pest is best approached under the concept of integrated pest management (IPM).

Development of IPM systems for newly established and damaging forest pests will undoubtedly require accelerated research and action programmes to establish host/pest interactions, identify site and stand conditions which favour the pest, evaluate effects of local natural enemies, and project potential resource damage. Additional actions may involve search and screening of natural enemies in the pest's native habitat for possible introduction and release, a search for genetically resistant or tolerant strains of host trees and evaluation of silvicultural measures to maintain host vigour and hopefully, resistance to attack. Monitoring of populations and damage must be an integral part of an IPM programme to ensure early detection, define areas requiring treatment and to evaluate programme effectiveness. Chemical pesticides are an integral part of IPM but should be used sparingly and only to protect critical resource values. Use of chemicals in areas where natural enemies have been released should be avoided.

FAO is engaged in assisting member countries on several fronts with regard to the management of both exotic and indigenous forest pests. The nature of assistance that is being provided can be classified into several areas including awareness, networking emergency response and institutional capacity building.

Through FAO's Regular Programme1, a number of activities are being been carried out to increase the awareness of destructive forest pests and to encourage cooperation and exchange of technical information between countries at the regional and sub-regional level FAO journals such as Unasylva, Ceres and Plant Protection Bulletin often include reports of significant forest pest damage worldwide. The Organization also publishes a number of special papers which describe losses caused by various destructive agents and how these losses might be minimized. An example is the FAO paper, prepared by Dr. Banpot Napompeth of Thailand, on the leucaena psyllid in the Asia-Pacific Region that has beer distributed at this workshop (Napompeth 1994). We hope that this paper, which reviews experiences with leucaena psyllid in Asia and the Pacific will provide valuable reference material for planning and executing IPM projects against this insect in Africa.

Workshops are an important means for bringing people together with common concerns to exchange information and ideas. Since 1991, the FAO Forestry Department, thanks to financial assistance provided by USDA Forest Service through its Tropical Forestry Program, has had the opportunity to collaborate with three member countries in the organization of workshops on forest pests of mutual concern. These include the 1991 workshop on conifer aphids held in Muguga, Kenya, the regional conference on the European wood wasp, Sirex noctilio, held in Florianopolis, Brazil in 1992 and this workshop on leucaena psyllid, organized by the Tanzania Forest Research Institute (TAFORI). The list of collaborators in this workshop on leucaena psyllid is particularly impressive. In addition to FAO and USDA Forest Service, the CAB International Institute of Biological Control (IIBC), the International Centre for Research on Agroforestry (ICRAF), and the Sokoine University of Agriculture are workshop collaborators. This clearly reflects the concern for this latest threat to Africa's forest resources.

A series of expert consultations on pest related hazards of moving tree germ plasm has been proposed to be conducted by the International Plant Genetics Resources Institute (IPGRI). The first of these is in the planning stages and will focus on eucalypts.

Regional and sub-regional networks, designed to provide continuing exchange of information, experts, biological materials and test results can extend the momentum initiated by workshops such as the one we are participating in today. In 1991, as a result of the conifer aphid workshop, there was some interest expressed in establishing a forest pest network for the countries of eastern and southern Africa. Since that workshop, the IIBC Kenya Station has taken the initiative to begin such a network. The present workshop has on its agenda, a discussion topic on networks. Hopefully we can explore how the work initiated by IIBC can be continued and expanded.

Assistance has been provided through FAO's Field Programme to a number of member countries to help them respond to damaging pest outbreaks. In 1991, assistance was provided to the Kenya Forest Department through the FAO Technical Cooperation Programme (TCP) to initiate work on the management of cypress aphid. This enabled the Forest Department to survey infested areas, treat high value sites with chemicals and begin a search for natural enemies of this insect. This project served as an important bridge to two longer term projects designed to address the cypress aphid problem in Kenya, funded by UNDP and World Bank. These projects have resulted in a stronger capacity within Kenya to address not only the cypress aphid problem but other forest pests as well. They are also providing a key linkage to the IIBC regional conifer aphid biological control programme. TCP assistance is also being provided to Nigeria for control of Oriental scale of neem, to Niger for monitoring and assessment of a decline of neem and to China to enable foresters and plant quarantine officers to recognize infestations of potentially destructive insects in log imports. A sub-regional TCP on the management of leucaena psyllid recently approved for Kenya and Tanzania is also in progress and should provide benefits throughout the region as a result of networking and technical cooperation.

There are many challenges and opportunities associated with protecting forests from damage by insects, diseases and other pests. These challenges will increase in the future as the risk of new pest introductions increases. Pests and diseases do not respect international boundaries. Consequently neighbouring countries and international organizations must work together to help prevent the spread and resultant resource damage caused by these destructive agents.

Blais, J.R. 1985. the ecology of the eastern spruce budworm: A review and discussion. Recent Advances in Spruce Budworm Research, Canadian Forestry Service, Ottawa, Canada, pp 49-59.

Ciesla, W.M., 1988. Pine bark beetles: a new pest management challenge for Chilean foresters. Jour. Forestry 86:27-31.

Ciesla, W.M., 1992. Bark beetles and wood borers in conifer logs exported from western North America into the People's Republic of China. FAO Plant Protection Bulletin. 40:154-158.

Ciesla, W.M., 1993a. Recent introductions of forest insects and their effects: A worldwide overview. in Proceedings, Conferência Regional da Vespa da Madiera, Sirex noctilio, na América do Sul, Florianólpolis, SC, Brazil. EMBRAPA, FAO, USDA Forest Service and FUNCEMA, pp 9-21.

Ciesla, W.M., 1993b. Recent introductions of forest insects and their effects: A global overview. FAO Plant Protection Bulletin. 41:3-13.

Ciesla, W.M., 1993c. Pests and diseases of neem. in Genetic Improvement of Neem: Strategies for the Future. Proceedings of the International Consultancy on Neem Improvement, Bangkok, Thailand 18-22 January, 1993, Winrock International institute for Agricultural Development, pp 95-106.

Debarr, G.L., 1992. Status of a mealybug, Oracella acuta Lobell, introduced into China from the southeastern United States - Trip report. USDA Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Athens, Georgia, Typewritten report, 50 pp.

Deutscher Bundestag, 1993. Waldschäden durch Schammspinnerraupen. Drucksachje 12/5859 13 pp.

Doane, C.C. and M.L. McManus (ed), 1981. The gypsy moth: research toward IPM, USDA Forest Service, Technical Bulletin 1584.

FAO, 1993. Forest Resources Assessment 1990, tropical countries. FAO Forestry Paper 112, 59 pp + annexes.

Hofacker, T.H., M.D. South and M.E. Mielke, 1993. Asian gypsy moths enter North Carolina by way of Europe: A trip report. Gypsy Moth News, USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Area, Issue No 33.

Jacobs, M.R., 1979. Eucalypts for planting. FAO Forestry Series 11, Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome, 677 pp.

Manion, P.D., 1991. Tree disease concepts. Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 402 pp.

Miller-Weeks, M., W.G. Burkman, D. Twardus and M. Mielke, 1994. Forest health in the northeastern United States. Journal of Forestry 92:30-33.

Morgan, F.D., 1994. Forty years of Sirex noctilio and lps grandicotlis in Australia. New Zealand Journal of Forest Science 19:198-209.

Napompeth, B., 1990. Leucaena psyllid in Thailand - A country report. In Leucaena Psyllid: Problems and Management, Proceedings International Workshop, Bogor, Indonesia, 16-21 January 1989, Winrock International Institute for Agricultural Development, pp. 45-53.

Napompeth, B., 1994. Leucaena psyllid in the Asia-Pacific Region: Implications for its management in Africa. FAO RAPA Publication 1994/13, Bangkok, 27 pp.

Owuor, A.L. 1991. Exotic conifer aphids in Kenya, their current status and options for management. Workshop Proceedings, Exotic Aphid Pests of Conifers, A Crisis in African Forestry. KEFRI/FAO pp. 58-63.

Pan Wuyao, n.d. Introduction of slash pine mealybug, Oracella acuta, in Guangdong Province of China. Typewritten report, 4 pp.

USDA, 1991. Pest risk assessment of the importation of larch from Siberia and the Soviet Far East. Forest Service, Misc. Pub. 1495.

USDA, 1992. Asian gypsy moth emergency declared in U.S. Pacific Northwest. USDA Press Release, Washington DC.

Waterhouse, D.F. and K.R. Morris, 1987. Heteropsylla cubana (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) - Leucaena psyllid. Biological Control, Pacific Prospects, Inkata Press, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 33-41.