FOOD SECURITY: SOME MACROECONOMIC DIMENSIONS1

The year is 1996. The subject is food security, which is defined as the access for all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life.2 FAO has planned and prepared a World Food Summit for 13 to 17 November 1996 in Rome with the slogan "Food for All". The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) organized a ministerial conference on the same subject in June 1995; over the past few years, the world's attention has been focused on the myriad issues surrounding food security in its many dimensions. A plethora of papers, monographs, reports and articles have explored, described and analysed the multiple facets of food security.

Indeed, FAO in preparing for the World Food Summit has published three volumes containing 15 papers on subjects related to food security ranging from the ethics of food security to investment for food security (Box 14). In addition, a policy statement and plan of action for adoption by heads of state and governments or their representatives at the Summit have been drafted, taking into account the views of governmental and non-governmental participants in the preparatory process.

Much of this work on food security has in fact been concerned mainly with food insecurity and has until relatively recently focused on the adequacy (or inadequacy) of food production to meet the nutritional needs of a growing population at the global or regional level. While production is of course important, and efforts to increase it need to continue with renewed vigour, it is only part of the picture; farmers do not grow food for altruistic reasons, but to feed themselves and their families through either production or sales, and in most developing countries the majority of the population is directly or indirectly dependent on agriculture. Furthermore, consumers (including many farmers) purchase food and in the absence of sufficient purchasing power they are unable to exert effective demand for food. In this special chapter, the question of food security is examined from a macroeconomic perspective.

The story starts rather unconventionally with a look at the economic development of Europe over the last five to six decades in order to understand what constitutes food security and provide a basis for understanding the problems of food insecurity (much as the medical profession studies health as a means of understanding disease). After a brief review of the conditions, mainly in Europe, in the aftermath of the Second World War, from which postwar thinking about food security evolved in the developed and developing countries as well as in the transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe and the former USSR, the chapter goes on to compare the food supply projections of FAO, IFPRI and the World Bank and concludes that, while there is no room for complacency and investment and technological progress must continue, sustainable food production, even for a growing population, is not the major issue. The question of effective demand for food is. In other words, the issue at stake is can people afford to buy the food that is available, and to purchase enough to ensure an adequate diet?

BOX 14 Synthesis of the Technical Background Documents |

The chapter then moves on to a discussion of the critical role of governments in choosing the appropriate combinations of monetary, fiscal, trade, investment and social policies to create an economic environment that is conducive to the attainment of food security. Although no individual government can control international economic conditions and the economies of many countries are too small to be able even to influence those conditions, each government is responsible for determining its domestic policies in the light of those conditions. The various policy responses of government and the international community required to deal with short-term fluctuations and long-term trends are then explored. The chapter examines a range of issues that affect a country's ability to achieve food security, including: the domestic macroeconomic and trade policies; food reserve stocking; the domestic generation of foreign exchange; foreign exchange and balance of payments support for food security from international agencies; the role and use of futures markets for stabilization; and the importance of debt reduction for the severely indebted low-income countries. Factors and policies affecting overall economic growth and their differential effects on the urban and rural economies are explored in order to examine food insecurity in both urban and rural areas, and what can be done in policy terms to increase food security.

Although sound economic policies are necessary for the achievement of food security, they are not easy to implement in the absence of real political consensus. In the final analysis, food security in any country is the responsibility, and must be under the authority, of the national government in conjunction with local authorities working with concerned groups and individuals within society. The international community and international agencies can assist, but cannot substitute for the actions and political will (which reflects both the scope and the limits of political action) to achieve food security within the country itself.

The desire to achieve some level of food security is as old as humankind itself. Until the last decade or so, the debate in most countries worldwide focused largely on the adequacy of food production to meet domestic needs, with a concomitant national policy emphasis on self-sufficiency in the supply of agricultural products. This focus, especially in the developed countries, has to be seen in the context of the Second World War and its aftermath, which had a profound effect on the minds of governments and societies. Throughout western, Central and Eastern Europe, for example, the years of the Second World War saw real food shortages caused not only by the disruption of agricultural production, but also (and for some countries this was much more important) by supply requisitioning and disruption of international trade and internal marketing arrangements. The early post-war years were characterized by economic reconstruction and tight exchange controls to conserve scarce foreign exchange reserves and these restricted the ability to feed the population through agricultural and food imports, although the existence of "currency zones" (such as the sterling area and the rouble zone) and the Marshall Plan enlarged the trading possibilities beyond national boundaries. Food rationing and price controls for both urban and rural consumers were used to ensure an equitable allocation of the food available during the war, and these were phased out over several years after the war's end. At the same time, policy measures to encourage the expansion of agricultural production on a long-term basis rather than to meet the immediate crisis needs were introduced and the emerging welfare states cast wide safety nets to protect the vulnerable sections of the population, including the poor, the sick, the elderly, the unemployed, the mentally and physically disabled and children.

The circumstances that produced these agricultural and food policy responses were characterized by a period of reconstruction and rehabilitation for countries that were already industrially advanced with relatively small and declining agricultural sectors and low population growth rates. While special incentives were provided to agriculture, this was not done at the expense of industry. In western Europe, for the 15 countries that now constitute the European Union (EU), the annual growth rates of agricultural and industrial production for the years 1948 to 1958 were 3.5 percent and 7.3 percent respectively, while average population growth was 0.7 percent per annum. Exports grew at about 9 percent per annum compared with 6 percent for imports.

After the period of reconstruction, industrial and agricultural output growth rates slowed, but the volume of trade, including agricultural and food products, soared, with imports and exports growing, and continuing to grow, at an annual rate of about 11 percent.3 The relative decline of the importance of the agricultural sector in terms of the economy as a whole meant that although the budgetary costs of agricultural support remained high in absolute terms, they decreased as a proportion of national expenditure.

The outcome of the post-war agricultural policies (and not just in the countries covered by the Common Agricultural Policy [CAP] of the EU because all countries made similar efforts to increase agricultural production) has been high levels of self-sufficiency in agricultural production - of well over 100 percent in many temperate-zone products, although this does not mean that each country is more than 100 percent self-sufficient in every product. The EU is a substantial importer and exporter of agricultural and food products with the rest of the world, even though a large proportion of its trade is intra-EU, and it has made an important contribution to increasing world food supplies.

Given this record, it might seem inappropriate to question whether the EU can be said to have achieved food security and in what sense it may or may not have done so. These questions are important, however, because the mindset that laid so much stress on agricultural self-sufficiency in the light of the wartime experiences has only recently begun to change in western Europe, and the transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe now have to face similar questions as they reorient their agricultural and food policies. So it is important that food security be defined clearly.

Food security has been defined as the access for all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life. The three key ideas underlying this definition are: the adequacy of food availability (effective supply); the adequacy of food access, i.e. the ability of the individual to acquire sufficient food (effective demand); and the reliablity of both. Food insecurity can, therefore, be a failure of availability, access, reliability or some combination of these factors.

Inherent in this modern concept of food security is an understanding of food producers and consumers as economic agents. Food availability is the supply of food, which depends, inter alia, on relative input and output prices as well as on the technological production possibilities. Food access is concerned with the demand for food, which is a function of several variables: the price of the food item in question; the prices of complementary and substitutable items; income; demographic variables; and tastes or preferences.4 According to Barraclough, to ensure food security, a food system should be characterized by:

It is worth adding explicitly that a secure food system must be able to deliver inputs and outputs (both those produced and consumed domestically and those traded internationally) where and when they are required.

Within this understanding, is the EU, for example, food secure?

[It] cannot really be claimed that the high levels of self-sufficiency experienced in most branches of EC [European Community] agriculture make a positive contribution to the level of food security enjoyed by the EC's citizens. It is helpful to draw a distinction between self-sufficiency in production and a self-sufficient farming system. The EC's high levels of self-sufficiency in production are often dependent upon heavy use of imported or exportable animal feeds and fuels which are just as susceptible to economic or military blockade as are the foods they produce; and provide no relief for local harvest failure.6

So it cannot be agricultural self-sufficiency that makes the EU food secure, yet food secure it undoubtedly is at the level of the EU itself and of each member state in circumstances short of the cataclysmic. The high post-war levels of economic growth, together with low population growth rates, have resulted in high and growing levels of material prosperity for the majority and the provision of safety nets for the vulnerable. The increasing levels of agricultural productivity and total output, new technologies for food processing and storage, good distribution infrastructure and, critically, an economic system that supplies the goods that consumers wish to purchase have resulted in the availability of a wide range of high-quality and safe foods for domestic consumption and export. In spite of the fact that the policy measures used to implement CAP led to higher consumer prices than would alternative measures, rising consumer incomes and declining real prices of agricultural produce mean that the share of food expenditure in the household budget continues to decline. For all practical purposes, the EU participates in a liberal trading environment on the basis of fully convertible currencies, which, together with strong and stable links with its main trading partners, ensures its ability to import at will. It is this bundle of characteristics that underpins food security in the EU and also in the rest of western Europe as well as such countries as Japan, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, the Republic of Korea, Taiwan Province of China, Hong Kong and Singapore. In practice, this is also true of the United States, although the size and nature of its resource base and infrastructure are such that of all the developed countries, it is perhaps the least vulnerable to external events.

Nevertheless, there are pockets of food insecurity in even the richest countries because food security at the national level does not mean that every household in the country is food secure. The meshes of the safety net may be too large to prevent some individuals and specific groups of individuals from falling through and government policies in several industrialized countries have tended recently to increase the mesh size. A proportion of the population can be living in absolute, not just relative, poverty. Within countries, the food-insecure poor comprise different sub-groups, differentiated by location, occupational patterns, asset ownership, race, ethnicity, age and gender. Thus, at the household or individual level there may be problems of food insecurity caused by inadequate access to food. The relationship between national and household food security is one of the most important and difficult issues confronting governments in all countries at all levels of wealth and development. It is further complicated by the fact that "having adequate household access to food is necessary but not sufficient for ensuring that all household members consume an adequate diet... and consuming an adequate diet is necessary but not sufficient for maintaining a healthy nutritional status".7 A distinction has sometimes been made between chronic and transitory food insecurity at the household level.8 Chronic food insecurity involves a continuously inadequate diet caused by the persistent inability to acquire food. Transitory food insecurity is a temporary lack of adequate food access for a household, arising from adverse changes in food prices, food production or household incomes. With this perspective, the policy options for reducing food insecurity are seen as depending on whether the case is chronic or transitory. Measures to address chronic food insecurity would include increasing the food supply, focusing on development assistance or income transfers for the poor and helping the poor to obtain knowledge about nutrition and health practices. Transitory food insecurity could be ameliorated by stabilizing supplies and prices and assisting vulnerable groups with emergency employment programmes, income transfers or food. How useful this distinction is in making policy choices is open to question. For instance, how temporary is "temporary"? Are the unwanted food insecurity effects of structural adjustment and transition programmes temporary or chronic? Do we have to know before we decide how to deal with them?

The answer is "no". The need is for policy measures that address all aspects of food insecurity with a view to providing the vulnerable with safety nets (which can vary over an individual's lifetime and in response to external emergencies) and to creating the conditions that can lead to an eradication of endemic hunger. This requires economic growth. Countries that have seen negative (or stagnant) growth rates of agricultural production and GDP with a growing population have ever-diminishing resources (which were often very small to start with) to share among an increasing number of people. Improving the equitableness of income distribution can only achieve limited results in these circumstances and, as has frequently been seen, will be strongly resisted by the potential losers. So growth is necessary and, against a background of economic growth, experience shows that it is less difficult (although still never easy) to implement measures that increase equity, particularly if the growth is broadly based to include the agricultural sector. Indeed, many if not all of the countries that are now regarded as being food insecure are characterized by an agricultural sector on which a large proportion of the population still depends directly or indirectly for a livelihood, and this was not true of post-war Europe. Increasing agricultural productivity and incomes in such countries therefore increases the effective demand for food and so is at the heart of improving food security. One of the lessons that can be learnt from Europe, however, is the importance of economic policies that at least do not discriminate against agricultural development and growth.

It is clear from the foregoing discussion that the subject of food security in its most complete sense touches on many different technical disciplines, each of which provides a partial illumination of some of the complex issues at stake. This chapter is written from a political economy perspective and focuses on some of the major economic and trade policies that bear on the achievement of food security.

WHAT ARE THE PROSPECTS FOR WORLD FOOD SECURITY?

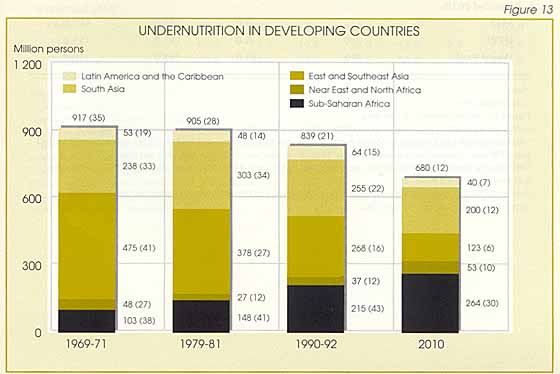

On a global level, food security for all requires that the supply of food be adequate to meet the total demand for food. While this is a necessary condition for the achievement of food security, it is by no means sufficient. Although currently enough food is supplied globally, it is estimated that in 1990-92 some 839 million people in the developing countries had inadequate access to food, fundamentally because they lacked the ability to purchase or procure enough, that is, they lacked the means to exert effective demand. This figure, unacceptably high though it is, reflects a substantial degree of progress since the beginning of the 1970s; the number has declined in absolute terms from about 917 million and in relative terms from 35 percent of the population of developing countries to 21 percent, mainly as a result of progress in East Asia (including China) and parts of South Asia, such as India and Pakistan. The situation is most serious in Africa where the number of chronically undernourished people in the sub-Saharan countries more than doubled over the period according to FAO estimates.9 Figure 13 shows the past and projected changes in the number of undernourished people in the developing countries.

What are the medium-term prospects for food supply and demand? FAO, IFPRI and the World Bank have all attempted to make projections to the year 2010.10 Although there are some problems with comparability because of such factors as the differences in base year data, country and commodity coverage and regional definition, indicative comparisons of production, total use and net trade in cereals are possible. The results of the three models are presented in Tables 6 to 9.

TABLE 6 | ||||

Data for 1989-91 and projections comparisons for all cereals (rice milled): developed countries | ||||

World |

Developed countries | |||

Former centrally planned economies1 |

Other industrialized2 |

Total | ||

(............................................... million tonnes ...............................................) | ||||

Production |

||||

Actual 1989-91 |

1 726.5 |

266.0 |

597.8 |

863.8 |

Projected 2010 |

||||

FAO |

2 334.0 |

306.0 |

710.0 |

1 016.0 |

IFPRI |

2 405.0 |

324.0 |

785.0 |

1 174.0 |

World Bank |

2 311.0 |

324.0 |

733.0 |

1 058.0 |

Total use |

||||

Actual 1989-91 |

1 729.8 |

302.1 |

475.0 |

777.1 |

Projected 2010 |

||||

FAO |

2 334.0 |

301.0 |

553.0 |

854.0 |

IFPRI |

2 406.0 |

381.0 |

634.0 |

1 015.0 |

World Bank |

2 308.0 |

308.0 |

540.0 |

848.0 |

Net trade |

||||

Actual 1989-91 |

3.6 |

-37.2 |

129.7 |

92.5 |

Projected 2010 |

||||

FAO |

... |

5.0 |

157.0 |

162.0 |

IFPRI |

-1.0 |

8.0 |

151.0 |

159.0 |

World Bank |

0.0 |

15.0 |

195.0 |

210.0 |

Notes: | ||||

TABLE 7 | ||||||||||

Data for 1989-91 and projections comparisons for all cereals (rice milled): developing countries | ||||||||||

Developing countries | ||||||||||

Sub-Saharan Africa |

Near East and North Africa1 |

Asia and the Pacific |

Latin America and the Caribbean |

Others |

Total not allocated by region | |||||

South Asia1 |

China including Taiwan2 |

Others |

||||||||

(........................................................ million tonnes ........................................................) | ||||||||||

Production |

||||||||||

Actual 1989-91 |

54.7 |

76.8 |

202.8 |

326.8 |

104.6 |

97.0 |

... |

862.7 | ||

Projected 2010 |

||||||||||

FAO |

110.0 |

119.0 |

292.0 |

473.0 |

165.0 |

159.0 |

... |

1 318.0 | ||

IFPRI |

86.0 |

118.0 |

297.0 |

426.0 |

153.0 |

152.0 |

... |

1 232.0 | ||

World Bank |

83.0 |

97.0 |

282.0 |

475.0 |

151.0 |

144.0 |

20.0 |

1 253.0 | ||

TOTAL USE |

||||||||||

Actual 1989-91 |

64.7 |

114.2 |

203.3 |

339.8 |

119.3 |

111.4 |

... |

952.7 | ||

Projected 2010 |

||||||||||

FAO |

129.0 |

191.0 |

302.0 |

488.0 |

185.0 |

185.0 |

... |

1 480.0 | ||

IFPRI |

118.0 |

183.0 |

307.0 |

440.0 |

176.0 |

165.0 |

3.0 |

1 392.0 | ||

World Bank |

96.0 |

169.0 |

312.0 |

502.0 |

189.0 |

172.0 |

20.0 |

1 459.0 | ||

NET TRADE |

||||||||||

Actual 1989-91 |

-8.5 |

-38.4 |

-3.2 |

-14.7 |

-12.7 |

-11.3 |

... |

-88.8 | ||

Pro jected 2010 |

||||||||||

FAO |

-19.0 |

-72.0 |

-10.0 |

-15.0 |

-20.0 |

-26.0 |

... |

-162.0 | ||

IFPRI |

-32.0 |

-65.0 |

-10.0 |

-14.0 |

-23.0 |

-13.0 |

-3.0 |

-161.0 | ||

World Bank |

-14.0 |

-73.0 |

-31.0 |

-22.0 |

-37.0 |

-28.0 |

-5.0 |

-210.0 | ||

Notes: | ||||||||||

TABLE 8 | ||||

Annual percentage growth rates of production and total use of all cereals: developed countries | ||||

World |

Developed countries | |||

Former centrally planned economies1 |

Other industrialized |

Total | ||

(.............................................. million tonnes ..............................................) | ||||

PRODUCTION GROWTH RATES |

||||

Actual 1970-80 |

2.7 |

1.4 |

2.9 |

2.4 |

Actual 1980-91 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

0.2 |

0.6 |

Projected 1989-91 to 2010 |

||||

FAO |

1.5(1.6) |

0.7 (0.5) |

0.9 (1.1) |

0.8 (0.9) |

IFPRI |

1.7 (1.6) |

1.9 (1.5) |

1.4 (1.3) |

1.6 (1.4) |

World Bank |

1.5 (1.2) |

1.0 (0.2) |

1.0 (0.8) |

1.0 (0.8) |

TOTAL USE GROWTH RATES |

||||

Actual 1970-80 |

2.5 |

2.9 |

0.9 |

1.6 |

Actual 1980-91 |

1.8 |

0.1 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

Projected 1989-91 to 2010 |

||||

FAO |

1.5 (1.5) |

0.0 (-0.1) |

0.8 (0.8) |

0.5 (0.4) |

IFPRI |

1.7 (1.6) |

1.2 (0.9) |

1.5 (1.3) |

1.3 (1.1) |

World Bank |

1.5 (1.4) |

0.1 (-0.4) |

0.1 (0.7) |

0.4 (0.3) |

Notes: | ||||

TABLE 9 | |||||||

Annual percentage growth rates of production and total use of all cereals: developing countries | |||||||

Developing countries | |||||||

Sub-Saharan Africa |

Near East and North Africa1 |

Asia and the Pacific |

Latin America and the Caribbean

|

Total | |||

South Asia1 |

China including Taiwan2 |

Others |

|||||

(............................................................. million tonnes .............................................................) | |||||||

PRODUCTION GROWTH RATES |

|||||||

Actual 1970-80 |

1.4 |

2.8 |

2.7 |

4.0 |

3.0 |

2.4 |

3.1 |

Actual 1980-91 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

2.5 |

0.6 |

2.7 |

1989-91 to 20103 |

|||||||

FAO |

3.5 (3.4) |

2.2 (2.3) |

1.8 (1.8) |

1.9 (2.0) |

2.3 (2.1) |

2.5 (2.3) |

2.1 (2.1) |

IFPRI |

2.3 (2.4) |

2.2 (2.1) |

1.9 (2.2) |

1.3 (1.6) |

1.9 (1.9) |

2.3 (1.8) |

1.8 (1.9) |

World Bank |

2.1 (3.3) |

1.2 (1.9) |

1.7 (1.6) |

1.9 (1.6) |

1.9 (1.8) |

2.0 (2.1) |

1.9 (1.8) |

TOTAL USE GROWTH RATES |

|||||||

Actual 1970-80 |

2.5 |

4.5 |

2.2 |

4.4 |

3.2 |

3.9 |

3.6 |

Actual 1980-91 |

3.1 |

3.6 |

3.0 |

2.6 |

3.2 |

1.5 |

2.8 |

1989-91 to 20103 |

|||||||

FAO |

3.5 (3.4) |

2.6 (2.5) |

2.0 (1.8) |

1.8 (1.9) |

2.2 (2.1) |

2.6 (2.4) |

2.2 (2.2) |

IFPRI |

3.0 (3.0) |

2.4 (2.2) |

2.1 (2.3) |

1.3 (1.7) |

2.0 (2.1) |

2.0 (1.7) |

1.9 (2.0) |

World Bank |

2.0 (3.1) |

2.0 (2.4) |

2.2 (2.0) |

2.0 (2.1) |

2.3 (2.1) |

2.2 (2.5) |

2.2 (2.2) |

Notes: | |||||||

BOX 15 Opinions differ about the role China will play in the world grain market. Estimates of China's net grain imports over the next 15 to 30 years range from a forecast of fundamental self-sufficiency to a very unlikely high of 200 million tonnes depending on the assumptions made about several key parameters. A number of sources maintain that China's grain imports could reach 30 to 40 million tonnes, an amount that is less than the former USSR imported in the late 1980s and that would have little effect on the long-term real price of grain. To economize on transport costs and facilities, most of these imports are likely to go to the large cities and coastal region, thus assuring adequate supplies at stable prices. As a result of policy changes made in 1994, Beijing has delegated responsibility for the grain supply of each province to each provincial government. This means that Beijing has largely lost control of the national grain supply since provinces producing surplus grain can (and do) restrict exports to other provinces until they are certain their own needs have been met. This was one reason for the volatile price situation in 1994; grain did not readily move from the surplus to the deficit areas. Thus the move to a national market, which seemed assured by the 1993 reforms, has now been delayed, probably for several years and, if China does import enough grain for its large cities and the coastal area, the national market may well be delayed for decades. In recent years, China has procured about 80 million tonnes of grain domestically, although this figure was probably even lower in 1994 and 1995. Consequently, 40 million tonnes is a very large figure relative to the marketed grain in China. Although 30 to 40 million tonnes of grain imports is a possibility a decade or more into the future (wheat imports are some 11 million tonnes per year), whether the figure will in fact be that high depends on: what China does to encourage domestic grain production in terms of price policy, research, facilitating farm enlargement and ensuring adequate supplies of good-quality fertilizer; the rate at which the demand for livestock products grows; and the country's ability to generate foreign exchange. With regard to pricing policy, it was announced in March 1996 that state grain purchasing prices were to be raised by 20 percent to encourage increased production. New information from surveys in China and satellite pictures suggests that the grain area has been seriously under-reported, which means that the potential for yield increases is far greater than was previously thought. The survey data also suggest strongly that stocks have been substantially underestimated. In assessing the demand for livestock products there are serious discrepancies in the official data on meat and poultry production from the various sources. The output data for meat and poultry implied a per caput availability of more than 32.5 kg in 1993, while the household survey data put consumption at about half that amount. If per caput consumption was in fact 32.5 kg (which has since increased according to the same data measurement methods to about 38 kg), consumption growth should start to slow down, although there has not yet been any indication of this happening. What is perhaps more disturbing is that, while meat and poultry production is said to have increased substantially since 1985, per caput urban purchases only increased from about 22 kg in 1985 to 24.5 kg in 1993, with rural consumption increasing from 12 kg to 13.3 kg over the same period, according to the household surveys. Over the same period, the output of meat and poultry almost doubled from 19.3 million tonnes to 38.4 million tonnes, while the population increased by 12 percent. Another data series puts per caput consumption of pork, beef and mutton at 16.75 kg in 1985 and 27.37 kg in 1993, while yet another, on per caput consumption of selected consumer goods, puts per caput consumption of meat and poultry at 16.5 kg for 1985 and 22.6 kg for 1992. All of these figures are in the Statistical Yearbook of China. A major factor affecting future demand for grain is the consumption of meat. There is great uncertainty about how much meat is now being produced and consumed and how much grain is being used to produce meat, milk and poultry. Most of the published projections of future demand for and supply of grain fail to recognize the ambiguities in the data on the production and consumption of livestock products. The response of the government to rising imports is also critically important.1 Continued investment in agriculture and agricultural research, appropriate pricing policies and increased use of imported production technology, such as seed, are ways of boosting domestic supply. However, given that far larger import volumes than have hitherto been experienced seem probable, investment will also be needed in the marketing infrastructure and institutions to cope with the expanded grain trade. 1 S. Rozelle, J. Huang and M. Rosegrant. 1996. Why China will not starve the world. Choices, First Quarter 1996. |

It can be seen that there is broad agreement regarding projected annual percentage rates of change in production and total use at the global level and for all developing countries taken as a whole, as well as for some of the developing country regional groupings. The greatest divergences in opinion centre on the former centrally planned economies (CPEs), sub-Saharan Africa, the Near East and North Africa and China (see Box 15 on p. 276 for an alternative view of Chinese trade prospects), as well as on total use (essentially consumption) in Latin America and the Caribbean. The FAO and IFPRI projections for net trade at the level of aggregation of "total developed" and "total developing" countries are very close and substantially lower than those of the World Bank, which foresees a far more rapid growth in world grain trade largely as a result of expanded wheat imports into the Asian countries to meet changing consumer preferences away from rice. The FAO and IFPRI net trade projections are more variable for the regional groupings, most notably for sub-Saharan Africa, the CPEs and Latin America and the Caribbean.11

As in all exercises of this type, the outcomes are critically dependent on the validity of the assumptions made about the exogenous environment, rates of changes in the individual variables, the interaction among the different variables and the accuracy of the baseline data.12 Nevertheless, all three studies conclude that the growth in global supply will be sufficient to meet the growth in global demand, and all highlight sub-Saharan Africa as an area that should cause particular concern, whatever the deficiencies of the model might be.13 Although real world grain prices are expected to continue their long-term decline (despite the recent price spike),14 the rate of increase in the demand for food in sub-Saharan Africa is expected to outstrip that of supply, and the ability to meet the increasing demand would therefore depend on the ability of the individual countries to pay for those imports not covered by food aid.

The conclusion that global food supplies can increase fast enough to meet expected demand at constant or even declining real food prices leaves no room for complacency on the supply side. Continuing increases in agricultural output, be they through area expansion (absolutely, through multiple cropping or through reduced fallow periods) or productivity increases, require sustained efforts to improve agricultural technologies and their rate of adaptation and to avoid or reverse environmental degradation so that the output increases are not only sustained but sustainable. In other words, sufficient resources must be committed to investment in agriculture on a continuous basis if the projected potential output increases at global, regional and country levels are to be realized.

If there is no room for complacency on the supply side, there is even less on the demand side. The projections are not based on meeting basic nutritional needs, but on expected effective demand, i.e. the ability to pay. By the year 2010, it is expected that the absolute numbers of chronically undernourished people in the developing countries will have fallen - estimates vary depending on the assumptions made - to perhaps some 680 million, representing 12 percent of the population of these countries instead of 21 percent as at present. While it is reassuring to be told that the world can in principle produce enough food to meet likely demand, the probable inability of so many people to exert sufficient effective demand to feed themselves at even minimally adequate levels is deeply disturbing. Experiences in the countries that have made and are continuing to make good progress, even in the face of a difficult international economic environment, show that governments are the key players in implementing domestic and trade policies which can lead to the achievement of national food security and that economic policies are of particular significance.15

It is difficult to apply the concept of food security at the global or the regional level where region is defined on a geographical rather than a politico-economic basis. Sub-Saharan Africa has been identified as a region where food insecurity is likely to worsen. What this actually means is that a high proportion of countries in that region are expected to have a worsening food security position. Conversely, some of the regions that are expected to improve overall, or at least not to worsen, include individual countries that might see deterioration. The highest level of aggregation at which the concept can reasonably be made operational is that of the national government (the only realistic - and even then partial - exception to this would be the EU because of its degree of politico-economic cohesion) since the achievement of food security depends on action by those who have the power and the responsibility to act. This does not preclude the necessity for action by external agents, such as donor governments, international agencies, NGOs and multilateral and bilateral lenders, to support developing country governments in the fulfilment of their responsibilities.

Since the early 1980s, policy reforms initiated in many countries have been biased in favour of greater market orientation and a more open economy.16 There has been a movement away from the concept of development, including agricultural development, as planned change by public agencies. Indeed, this period has seen a serious questioning of the very role of government - what it should and should not properly do in a market economy. In this context, it is clear that government has a vital role to play if a functioning free-market economy, rather than one that is merely a free-for-all, is to emerge in such a way that the sustained and sustainable economic growth on which long-term national food security depends can occur and that its benefits are distributed equitably.

What then is the role of government and what can governments do that no other body can? Put simply, governments need to govern and this has traditionally been taken to mean securing the borders and protecting the population from both external and internal threat, i.e. keeping the peace without which food security is threatened. It also means ensuring the establishment and enforcement of a legislative and judicial system that defines the rights and obligations of individuals and legal entities, regulates their activities in the public interest and protects their agreed rights. A strong, fair and stable legislative framework is necessary to guide and regulate the individual players in the market and to ensure that they all play by the same set of rules through enforcement of the law so that market activity can contribute to food security for all. Only governments can create the favourable and stable macroeconomic and trade environment that can enable national food security to be realized. For countries in transition, be it from centrally planned to market economies, because of the implementation of structural adjustment policies or simply as a part of the normal process of economic development, the role of government is especially difficult. Governments need to invest in the infrastructure for progress. Inherent in this must be the recognition that investment in the development of human resources (building human capital of both women and men) and action to alleviate poverty add to, rather than subtract from, a country's growth potential and are essential for ensuring food security for all sections of the community. This type of investment includes the provision of those services and infrastructure that have a large public good component, such as education, health, public utilities and roads, and that cannot therefore be provided adequately by the private sector. In addition, the demands of adjustment or development might in some cases require the government to provide temporarily some of the services that can in principle be supplied by the private sector once the successful implementation of policy reform has allowed its capacities to develop sufficiently. In order to avoid stifling the development of the nascent private sector, any such activities, whether undertaken by governments or other agencies, need to be carefully planned and coordinated.

The achievement of food security on a sustainable basis therefore requires that governments take action on a number of different policy fronts. Trade and macroeconomic policies that permit and foster overall economic growth and increase competitiveness in export markets are needed; they should also correct past distortions that favour one sector of the economy to the detriment of others. Agricultural sector policies should be designed to promote sustained and sustainable sector growth in order to increase both domestic food supply and those agricultural and food exports for which the country has a comparative advantage. Although economic growth is very important for addressing the underlying causes of food insecurity, "economies cannot be expected to grow quickly enough to eliminate the chronic food insecurity of some groups in the near future, even under the best of circumstances. Moreover, long-run economic growth is often slowed by widespread chronic food insecurity. People who lack energy are ill-equipped to take advantage of opportunities for increasing their productivity and output".17 Furthermore, gross inequalities of income distribution may prevent the resource-poor from participating in the growth process and certain policy reforms may of themselves have substantial negative impacts on vulnerable groups in society. Special measures may be needed in the short and medium terms to deal with specific cases of food insecurity and to ensure that essential food imports can be financed. Over the long term, some special measures will always be needed, although their nature may change.

It must be re-emphasized that the successful implementation of agricultural and food policies alone cannot achieve a national objective of food security. The elimination of absolute poverty, the root cause of food insecurity, requires action across the board to enable people to escape the cycle of poverty and malnutrition that traps successive generations. Yet the achievement of food security does not have to wait for the eradication of poverty. It is repeatedly stated by international agencies, donor governments, world summits and just about everybody involved in development that the resources and the means to eliminate food insecurity exist, but that the problem is the lack of political will. If governments would only readjust their priorities accordingly, the problem could be solved - although discussion about the time-frame required is studiously avoided. "Success stories" tend to concentrate on the policies that a particular country has implemented without delving too deeply into the socio-political circumstances that enabled it to implement those policies. Rarely is it asked why the political will might be lacking:

Political will is journalistic shorthand for the overcoming of the conflicting interests, ideological blinkers and structural constraints that usually make it impossible for governments to do what is technically feasible and clearly necessary to solve a serious problem. The term contributes to good journalism, but poor social science. Social scientists have to explain why political will is lacking and what might be done to produce it.18

The findings of research on food systems by the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) are unusual in that the question of political will is raised explicitly. They cast doubt on the political possibilities, rather than the strictly technical ones, of rapidly improving food access for the very poor. This applies to industrialized countries who have widely differing levels of social and economic deprivation as well as to countries at other stages of development. Governments are, after all, dependent on the groups to whom they owe their support, and their room for manoeuvre is correspondingly restricted:

If the problem is really systemic, as the UNRISD team believes, then it can be dealt with effectively only through both fundamental public policy and social change. The latter implies new power relationships among individuals, social classes, groups and nations. Social changes do not come about easily. Convincing political leaders that hunger and poverty are serious and solvable social problems does not bring about political will, although in some circumstances it might help.... In alleviating hunger, politics matters.... How are sufficient political pressures generated to force governments to adopt effective strategies leading to rapid diminution of poverty and hunger? Answers are unique for each time and place. Where social forces have emerged capable of bringing about such policies, however, there have been at least three broad and closely interrelated social processes at work.19

The three social processes referred to are identified as: modernization processes - the social impact of economic growth and technical change; the rapidly increasing availability and dissemination of information, which contributes to social change by changing perceptions and ideologies; and popular participation - the mobilization and organization in a real sense of those previously excluded by lack of control over resources or influence over government. The interactions between political, social, economic and ecological systems and processes as they affect people's access to food - locally, nationally and internationally - are extremely complex and the problems admit of no easy solutions. It follows, and is frequently observed, that there is rarely anything as simple as a technical solution to a complex problem. To take a simple example, assume crop yields can be increased by increasing fertilizer applications, whether fertilizer will in fact be applied depends on many other factors, such as are fertilizer imports regarded as being sufficiently important for the government to guarantee foreign exchange availability on a reliable basis? can the distribution system get the fertilizer to the right place at the right time? do the farmgate prices for output justify its use? can farmers obtain the resources to buy it in the first place? and are some farmers restricted in their access to fertilizer for political or other non-economic reasons?20 It is important to note that here the issue is not so much the political will to establish state interventions or subsidies to encourage an otherwise uneconomical fertilizer use, but the political will to remove existing distortions or privileges.

There are many technical questions (covering a wide range of professional disciplines) concerning food insecurity that require technical answers. Should fertilizer be applied? In certain agro-ecological circumstances, if yields are to be increased, it should be. However, because the basic problems of food insecurity are not purely technical, the solutions are not purely technical either. So fertilizer will be applied only if the political, social and economic configuration determines that it shall be. The rest of this chapter examines some of the economic questions of food security and the policy implications for the governments concerned.

RELIABILITY AS A COMPONENT OF FOOD SECURITY: SHORT-TERM FLUCTUATIONS AND LONG-TERM TRENDS

It is an accepted legal precept that hard cases make for bad law; it could with equal justice also be said that short-term crises make for bad policy. This chapter was written against the background of a perceived global grain crisis, which is of its nature short-term while nevertheless having serious longer-term impacts on several low-income food-deficit countries (LIFDCs). While reacting to an urgent situation, it is important that the longer-term issues are not ignored.

The reliability component of food security concerns both availability and access and is often confused with stability, although the questions of what stability and for whom are rarely addressed explicitly. Weather and other acts of nature affect the stability of supply; abrupt changes in demand affect the stability of price; and the interaction of macroeconomic and sectoral policies within and across countries can affect both.

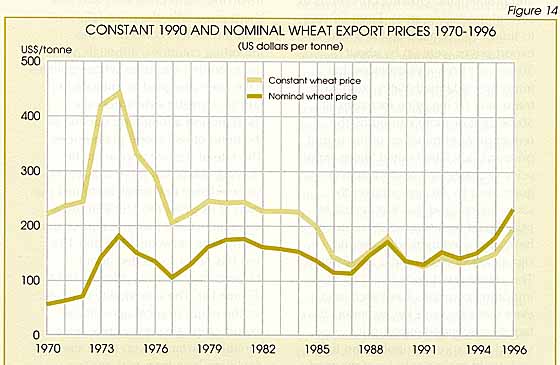

Fluctuations on the supply side of cereal production have a disproportionate impact on prices because of the relatively small short-term price elasticity of demand for cereals in the aggregate. A major cause of supply instability is a weather-induced shock such as occurred in the early 1970s, when the 1973 cereal crop fell to 3.5 percent below trend, and again in 1995 when the production fall was 3 percent below trend (the effects of this are still being seen). Adverse weather conditions in North America, northern Europe and major parts of the former USSR, together with failure of the monsoon in South Asia, resulted in the 1973 cereals crop being 3.5 percent below trend. This, given that the United States Government had decided in the late 1960s to stop holding large stocks, together with a number of other factors that occurred simultaneously (such as the first oil price shock and its aftermath, which contributed to increases in the prices of many agricultural inputs, and the change in Soviet policy to import cereals during domestic shortage rather than slaughter livestock herds) caused a sharp and rapid escalation of prices in international cereal markets (Figure 14).

A similar weather-induced phenomenon occurred in 1995, with a drop in global production to 3 percent below trend. World grain prices rose sharply during 1995 and further price increases are possible given the unusually low policy-induced stocks and problematic growing conditions in several producing areas. From January to June 1996, United States wheat export prices were up by about 30 percent from a year before, but importers of United States grain were frequently facing price increases of 50 percent or more caused by the reduction or elimination of the export price subsidy. The United States export price of maize, the leading coarse grain, rose by 46 percent over the same period, and this is reflected in prices paid by importers. Rice prices have also risen markedly, despite significant stocks in India and China. The grain import costs faced by many importing countries have increased even more because key exporters have largely suspended export price subsidies. Exporter supplies are tight and world grain stocks have dropped to the lowest level since the early 1970s, the stocks-to-use ratios for cereals being only 14 percent.

Current analysis and market information suggest that grain prices are likely to ease only after the 1996 output level is well defined. Serious drought or other indications of a significant production shortfall, however, could lead to higher and even more volatile prices. If crop conditions progress normally, wheat prices are expected to ease noticeably after the northern hemisphere harvest, perhaps in October and November when the expected large out-turn in Canada is known. The coarse grain market is susceptible to even greater short-term volatility as a result of heavy dependence on just one geographic region - the United States cornbelt area.

The grain market phenomenon is thus one of short-term fluctuations involving sharp price rises and less sharp price falls (the price falls are naturally of less concern to the importing countries, although not to the exporting countries whose policies have been designed to mitigate the falls to a greater extent than the rises) around a long-term decline in the trend of real world grain prices. The rate of decline appears to be slowing down, but there is as yet no real evidence that it has bottomed out. Even at its peak, the 1995/96 price spike reflected a lower real price than at any time between 1970 and 1985, and has never exceeded about 45 percent of the real price in 1974 (Figure 14). The commodity markets for the major tropical agricultural export crops also show great price variability around even more steeply declining long-term real prices.

The price impact of the weather-induced supply shocks of 1973 and 1995 on international markets was of longer duration in both instances than it would have been in an open-market, liberal trading environment because many countries, both exporters and importers, have policies that isolate the domestic market from the international market. This isolation means that price signals from the international market do not reach domestic producers or consumers, who therefore do not adjust to international market conditions. In effect, longer-lived instability is exported to the international market by these countries. The adjustment that occurs takes place within the few countries that have relatively open agricultural economies and tends to be large because the adjustment burden is not being shared by all.

Specific examples illustrate the effects of policy on international market stability. The EU, for instance, has long had in place a support policy for wheat producers that maintains a stable producer price, usually well above the international price. This is achieved through a variable levy system that maintains a constant threshold price, and this is the price paid by importers of wheat in the EU. A variable levy or tax based on the difference between the threshold price and the international market price is imposed on EU imports. To dispose of surplus wheat production into the export market, an export restitution is paid to exporters based on the difference between the domestic support or intervention price and the international market price.

In the cases of both the 1973 and 1995 production shortfalls, the international price for wheat rose above the threshold price and the EU switched from the variable levy and export restitutions to an export tax that maintained the level of the threshold price. Thus, just as EU producers were shielded from having to adjust to the normally lower and fluctuating international price by reducing production, they were also discouraged from adjusting to the higher international price by increasing production because of the export tax. The stabilization of consumer prices also meant that consumers had no incentive to adjust their consumption patterns to changing conditions in world markets. This means that the EU, a major producer of wheat, did not adjust production downwards in response to low international prices and, in fact, exported surpluses into the international market, thereby exacerbating the low prices. In addition, it did not adjust production upwards in response to a higher international price, instead it withheld exports into the international market, thereby exacerbating the international price rise. In the first instance, producers in adjusting exporting countries lost and consumers or governments in importing countries gained, while in the second instance producers in adjusting exporting countries gained and consumers or governments in importing countries lost. The CAP reforms of the early 1990s, including a set-aside provision, have dampened, but not totally negated, the effects described above. South Africa also took measures to stabilize domestic prices by halting grain export contracts in mid-1995. The United States policy reforms have involved a switch to partially and then fully decoupled deficiency payments, but at the same time there was, and still is, the Export Enhancement Program (EEP) (although its use has been suspended during the 1996 price spike). Both the United States and the EU have further dampened producer response to price fluctuations by the use of land set-aside schemes.

Consumers or governments are referred to in the above paragraph because a number of wheat-importing countries also shield themselves, this time their consumers, from changes in the international market price, particularly when that price rises precipitously. Such countries, sometimes using a parastatal marketing agency, purchase wheat in the international market at the international market price and sell into the domestic market at a higher price (tax) if the international price is low or at a lower price (subsidy) if the international price is high. So consumers in these importing countries are not forced to adjust to international market conditions, demand either too much or too little and force further adjustments into the international market. This increases the adjustment burden on those countries that do the adjusting.

As Johnson put it:

Much of the price variability in international market prices is man-made - it is the consequence of policies followed by many governments. In short, national policies that stabilize domestic prices for consumers and producers do so at the cost of international price variability unless the domestic price stability is achieved by holding stocks of sufficient size to create what is in effect a perfectly elastic supply curve for the relevant food product. But countries other than Canada, India and the United States have not held stocks of such size; consequently almost all national programmes of domestic price stability are achieved by varying imports and exports to make supply equal domestic demand at the predetermined and stable price. In this way, all the potential price effects of domestic demand and supply variations are imposed on the world market.21

Nevertheless, changes are occurring in the global environment within which international trade takes place; from the point of view of global and national food security, future strategies need to differ from those of the past. It is also clear that the food security policy responses to the short-term fluctuations and long-term trends need to be different.

There is an underlying concern about the possible disruption of world grain markets in the sense of price spikes caused by massive increases in demand by some of the major importing countries. The countries that are large enough to have the potential to do this are China and India; their size and geographical and agricultural diversity provides some cushioning of weather-induced shocks to domestic grain supply and also gives them export possibilities in good years. A summary of the situation and policies in each is given in Boxes 15, on p. 276, and 16. Box 17, on p. 290, provides an overview of the changing policies of the United States, the major grain exporter.

Over the past four decades, the United States has been the major intertemporal (interseasonal) stockholder of cereals, with the EU also maintaining significant grain reserves since the late 1970s when it became a net cereal exporter. Canada has at times carried far smaller grain reserves while neither Australia nor Argentina have had the storage capacity to do so. Food reserve stocks in India until very recently have been strictly domestic. The stocks held by both the United States and the EU were the result of agricultural policies that supported the domestic price above market clearing levels, requiring the authorities to purchase and hold stocks until a predetermined market price trigger allowed their release into the market. In addition, the various area set-aside schemes and the conservation reserve programmes, which held land out of cereal production, acted as a further complementary stock of grain, albeit in the form of uncultivated land rather than physical quantities of grain. These so-called policy-induced stocks will be drastically reduced or eliminated as market and trade liberalization occurs. This means that the world will no longer be able to rely on such policy-induced stocks to cushion the price effects of a production shortfall.

Two separate but related issues arise. First, what is likely to be the behaviour of the global cereals market in a more liberal trade and markets environment? Work is under way at FAO and elsewhere on analysing this question, but unfortunately only preliminary results are available at the time of writing. Economic theory and an empirical understanding of markets, however, can lead to some informed qualitative speculation. Consider the case of a reduction in world production. Without the cushion of policy-induced stocks to buffer the price rise in response to the production shortfall, the international price rise is likely to be sharper, but with more open economies and liberalized markets there will be greater international market price transmission to more producers and consumers in more countries. This should mean that a larger and quicker supply and demand adjustment will occur in response to the price change, with producers increasing output and consumers shifting consumption in favour of relatively cheaper foodstuffs. Future international market price spikes are therefore likely to be more violent initially, but shorter lived. Following on from this the question arises as to what extent the private sector will assume the stockholding function formerly borne by governments with policy-induced stocks. The private sector would not be expected to carry stocks of a similar magnitude becuase such levels would most probably be unprofitable. Nevertheless, the private sector will hold stocks up to a profitable level and to that extent those stocks would buffer and reduce the magnitude of market price spikes.

This discussion has focused on upward price movements. An examination of Figure 14, p. 284, shows that downward price movements have tended to be far less sharp and deep, reflecting the policies of some of the main grain-producing countries which have been designed to protect their farmers from severe price falls. To the extent that liberalization and policy reform remove or reduce the effects of such policies, the international market would see greater downward price variation than it has in the past. Thus in years of good harvests, price falls would be more pronounced, enabling importing countries to reap the benefits and providing perhaps greater profit incentives for private-sector stocking.

The second issue is that a number of countries may still feel the need to hold some level of food security reserve, as distinct from any working stocks held by private importers and traders. (Countries that do not will bear the full brunt of market instability.) These countries basically have two options; they can hold a physical stock of the commodity or they can hold a foreign currency fund for food security reserve purposes. The main advantage of this second option is that the country does not incur the significant costs of holding the actual commodity and of stock management and that it can earn interest on the hard currency account. However, the use of such a fund during periods of global supply shortfall will exacerbate the price spike. The trade-off for the country involved is the additional import cost caused by the price spike minus what has been earned on the foreign exchange account as compared with the cost of holding the commodity reserve until it is needed.

While a foreign exchange food security fund has both fiscal and monetary implications (e.g. tax revenues or borrowings to establish the fund, a positive balance of payments item and earnings on the fund until it is needed), a physical commodity stock reserve has mainly fiscal implications if purchased locally, but also monetary if acquired through imports. First there is the expense of establishing the stock reserve either through tax revenues or through borrowing. Then there are the maintenance costs associated with the reserve including stock administration, transport, storage, handling and rotation, which need to be financed from the same sources. Finally, distribution and replenishment costs are incurred when the food security reserve is called upon in accordance with the pre-existing rules governing its use. Ideally, the stock would be replenished when prices are low and depleted when high; but, as has been seen, policy reforms that permit substantial price falls have yet to feed through to the international market. The government budget for establishment, operation and management of the physical commodity food security reserve has an opportunity cost over and above the monetary cost for either government or the private sector. This opportunity cost may be great or small, depending on the alternative uses that might have been made of the funds. Given the shortage of both capital and recurrent budgetary funds in developing countries, the opportunity cost if properly calculated is likely to be very high.

BOX 16 India has put food security very high on the national agenda. From being a substantial net food importer in the 1970s, it was nearly self-sufficient in grain production from the early 1980s, more than self-sufficient in the 1990s and carries a high level of buffer stocks. The Food Corporation of India (FCI), which was instituted in 1965, is the main agency for the procurement, storage and transport of grains for distribution through the public distribution system and for maintaining the buffer stocks. The procurement and issue prices of food grains are fixed by the government; the issue price does not cover all the economic costs and the difference represents a government subsidy to consumers. The government also subsidizes the carrying costs of the buffer stocks, which amount to about 30 percent of the value of the stocks. In the past few years, grain output has increased considerably from around 180 million tonnes in 1992/93 to almost 192 million tonnes in 1994/95. Stocks had reached 28.7 million tonnes by March 1995, but transport and storage problems were slowing procurement despite increased output. Nevertheless, most of the wheat coming to market in 1995 was bought by FCI and other public-sector agencies under price support operations, with private traders handling only small quantities of very high-quality grain at prices well in excess of the support prices. By the end of the summer harvest season, stocks had reached between 36 million and 37 million tonnes, but these had been reduced to 29 million tonnes by November 1995. Plans to lower the issue prices of wheat and rice at state-run retail outlets to redress the price increases of previous years had to be postponed for budgetary reasons, despite the rising costs of carrying ever-increasing stocks. Export restrictions were lifted to allow exports of 2.5 million tonnes of rice and 2 million tonnes of wheat for the year, and there was pressure from the Ministry of Agriculture to have the ceilings abolished to permit greater reliance on exports and imports to manage food grain supplies. The most important constraints on increasing exports are inadequate storage, transport and port facilities. However, the removal of the public-sector monopoly on key aspects of infrastructure, including the ports, is encouraging new private-sector investment, and the redevelopment of the ports is expected to be finished by 1997. If this is achieved, some experts believe that India could be exporting 3 million tonnes of wheat and 4 million tonnes of rice by 2002 (rice stocks are currently running at 16 million tonnes). This would make it a major player in the small world rice market, where its prices are competitive. In the wheat market, however, it is less price competitive. There seems to be a strong consensus among the different political parties for continuing with the economic liberalization process while supporting agricultural development and giving high priority to food security. India therefore seems likely to engage more in international trade in grain markets in the future and will perhaps at some point decide to reduce its very large and expensive buffer stocks in favour of a greater reliance on imports. If so, India might play an even greater part in world markets once the port capacity has been modernized and expanded. |

The issue of food security stocking, either as a physical commodity or liquid reserves, nationally or multilaterally through the various fund facilities available, is highly complex in economic terms. When the non-economic factors are included, together with the country-specific conditions for both economic and non-economic factors, it is obvious that each country needs to address the question from its own perspective and to repeat the exercise as the important variables change. In determining government policy with regard to food security stocking, governments need to take account of private-sector activity in grain trading and storage and to decide what the respective roles of the public and private sectors should be.

No single small country is able to do anything about the world market. The question therefore is which policy measures, in addition to the trade-related economic policies discussed in the next section, can governments in low-income, food-importing countries introduce to ensure reliability of food availability and access, both in response to short-term fluctuations and over the longer term? IFPRI, for example, has suggested four sets of measures:

Many developing countries have found that strategies to keep grain affordable to consumers, such as holding large public grain stocks or setting ceiling prices, are unsustainably expensive. There are, however, things they can do:

hold small grain stocks to provide some insurance against price spikes;

use foreign exchange insurance or special credit arrangements, such as the International Monetary Fund's Compensatory Finance Facility [sic], to finance needed imports;

use world futures and options markets to hedge against future price increases;

invest in transportation, communication, and agricultural research to ensure competitive rural markets and enhance the capacity of farmers to respond to changing prices.22

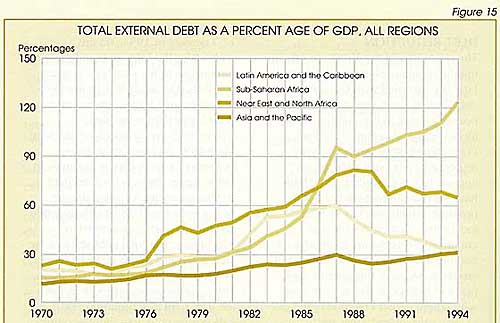

The first point, food stocks, has been addressed in this section. The last is covered in the next section in the context of trade-related economic policies. Points two and three are each given a section of their own because balance of payments support and the use of futures markets are increasingly being suggested by some international agencies and development experts as having vital roles to play in the achievement of food security in developing countries; however, as the following analysis suggests, both have very limited scope for assisting the poorest food-importing countries. Of far greater significance for more than 30 low-income countries is the external debt burden. While this is primarily a long-term concern it clearly has implications for the ability to respond to short-term food price shocks and a section of this Special Chapter is devoted to examining the consequences for food security of high levels of debt.

TRADE-RELATED ECONOMIC POLICIES

A country's trade-related economic policies influence food security indirectly through their effect on the growth of the economy as a whole and of particular economic sectors. They also have a more direct impact on food security and nutrition status by affecting such factors as rural and urban household incomes, the ability to import food to meet domestic shortfalls and demand for food items not produced locally and the earning of foreign exchange to finance the varying share of food imports in total imports:

The expansion of agricultural trade has helped provide greater quantity, wider variety and better quality food to increasing numbers of people at lower prices. Agricultural trade is also a generator of income and welfare for the millions of people who are directly or indirectly involved in it. At the national level, for many countries, it is a major source of the foreign exchange that is necessary to finance imports and development; while for many others, domestic food security is closely related to the country's capacity to finance food imports.... Agricultural trade policy has long reflected the widely held belief that, because of its importance and vulnerability, the agricultural sector could not be exposed to the full rigours of international competition without incurring unacceptable political, social and economic consequences. This view has led to high and widespread protection of the sector.23

It has been argued that the instability in commodity markets that has apparently resulted from agricultural border protection has in its turn led to further pressures for protection. Whether or not this is true, many developing countries have nevertheless implemented economic policies that have been biased against the production of tradable goods in general and exports in particular, as well as against agricultural products. Taxation of the agricultural sector has been high in several countries. A major research study by the World Bank covering 18 countries over a 25-year period found that: "The indirect tax on agriculture from industrial protection and macroeconomic policies was about 22 percent on average... nearly three times the direct tax from agricultural pricing policies (about 8 percent). The total (direct plus indirect) was thus 30 percent."24 The overall effect has been an average income transfer out of agriculture of 46 percent of agricultural GDP, ranging from 2 percent for the countries that protected agriculture to 140 percent for the heaviest taxers. In such countries, investment in food production has therefore been suboptimal and agricultural growth has been stifled, as has economic growth as a whole. Trade-related economic policy reforms and the ongoing structural adjustment programmes should lead towards correction of the long-standing anti-agriculture bias, if the reforms are carried out with real commitment and consistency. "The adjustment in Africa displays several weaknesses. From the evidence of recent policy actions, African governments have yet to display a real commitment to policy reform. Macroeconomic imbalances continue to characterize many economies, even those... that have been engaged in adjustment for more than a decade. Governments continue to interfere in markets."25 The same authors stress the critical role of exchange rate policy in stimulating growth and reducing poverty through the correction of economic disequilibria.

The maintenance of overvalued exchange rates is of particular significance as they impose a tax on exports and subsidize imports. This tool has been used at high cost to stabilize and hold down domestic food prices for urban consumers at the expense of the domestic producers of import-competing and exportable agricultural products, often in the face of severe domestic inflation which has been poorly controlled or exacerbated by economic policy measures. In the long term, therefore, the effects are damaging for food security as: structural changes in the tastes and preferences of urban consumers that do not take account of real international prices, as well as increasing urban incomes, exert pressure to maintain and increase food imports; the ability to pay for those imports has been reduced by depressing the expansion of agricultural and food exports which, for many low-income countries, are the main source of export earnings; the benefits of long-term falling real cereal prices have not been realizable in the face of high domestic inflation; and greater exchange rate overvaluation is related to lower GDP growth. Correcting overvalued exchange rates, which increases the domestic price of tradable food items, and controlling inflation, which slows down the rate of increase in domestic food prices and reduces the cost of stabilization measures, should therefore be put high on the policy reform agenda, and kept there. Rather than delay painful macroeconomic adjustment, which needs to allow for balanced sectoral growth by removing the biases against agriculture, governments may be better advised to implement compensatory interventions aimed at the groups most vulnerable to rises in the prices of tradable foods.

As noted earlier, there appears to be a long-term shift in the terms of trade away from the traditional agricultural export crops in favour of food crops. Thus, over time, a country's comparative advantage will change. Trade and macroeconomic policies, as well as sectoral pricing policies, need to permit the agricultural sector to respond to changes in comparative advantage patterns by reallocation of resources. However, in anticipation of these changes, governments need to invest in the long-term development of agriculture and the rural economy.

The implementation of appropriate trade and macroeconomic policies is critical for another important aspect of food security; the ability to finance the importation of food that is not produced domestically or is not produced in sufficient quantities, both when there are short-term price fluctuations and in order to meet the ongoing import needs reliably.

The sharp grain price rises of 1995-96 have increased the import bills of several countries. Many of the countries in Africa face significant problems with grain imports, especially in East Africa. Also, grain import requirements in North Africa are much higher than usual because of short crops in Morocco and Tunisia, although the normally high caloric intake levels in the area probably offer some flexibility in short-term use rates. Only a few Asian countries appear to be facing serious import problems, but the volume of grain could be substantial. The most significant problems are considered to be in Bangladesh and Afghanistan. Several countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are having difficulties with the higher prices of grain imports as grain output has recovered only slowly from the previous year's drought.

While increasing food aid is often the response to this type of situation, such a solution does not appear to be feasible at least in 1996/97. The overall level of food aid has been declining recently and was expected to be lower this year. Higher prices can be expected to reduce further the quantity of food aid, as most aid allocations are planned and budgeted in value terms. It is to be hoped that the lower food aid availabilities result in careful use of what funds there are in order that the needs of the most severely affected countries and regions can be met, although this would leave a significant number of other developing countries, which are generally in a marginal position with respect to financing grain import requirements, to search for alternative methods of finance in a period of higher prices.