|

The implications of the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture for developing countries |

||||

|

|

||||

|

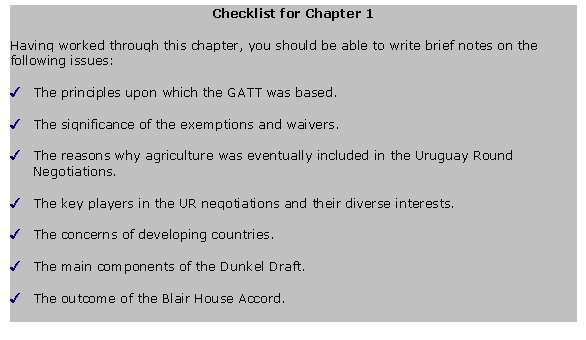

Chapter 1: An overview of the negotiations on agriculture |

||||

|

What this chapter is about

This chapter introduces the background to the Agreement on Agriculture. It provides a brief overview of the history of the GATT, noting its origins in the 1947 accord, the reasons for eventually extending the remit of the negotiations to include agricultural trade, and the countries and issues which dominated the discussions leading up to the Agreement.

Aims of this chapter

What you will learn

1.1 The background to the Uruguay Round negotiations

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was established in Geneva in 1947 to create a framework that would regulate international trade and stimulate international commerce. The World Bank and the IMF, that were established at Bretton Woods in 1944 in order to deal with matters of international finance, were associated initiatives. In addition to the latter two organisations, policy makers also envisaged the formation of an International Trade Organisation (ITO), that would oversee international trade and enforce a framework of rules. A charter for the ITO emerged from a 1946 conference in Havana, although this was never ratified by member governments.

As a result, the GATT continued to be governed by "provisional" and "interim" measures, and remained an agreement without a formal organisation to enforce it. The signatories to the GATT, known formally as contracting parties (rather than members) applied the GATT according to the Protocols of Provisional Application (PPA), and the secretariat that administered the GATT kept the title of Interim Committee of the International Trade Organisation (ICITO). These "provisional" arrangements persisted up until 1994, when the Final Act of the Uruguay Round eventually brought the World Trade Organisation (WTO) into being.

1.1.1 Objectives and Principles of the GATT

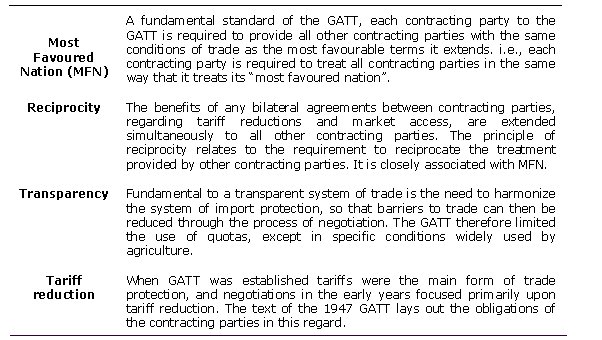

The objectives of the 1947 Agreement were to establish an orderly and transparent framework within which barriers to trade could be gradually reduced, and international trade thereby expanded. In order to facilitate this, the agreement contained within its text certain underlying principles and provisions that have been built upon over consecutive rounds of negotiation. The most important elements of the Agreement included those of:

Table 1.1 The Principles of the 1947 Act

Exceptions and waivers

The agreement also recognised that there are circumstances in which strict adherence to these principles would be inappropriate. The GATT therefore provided for exceptions and waivers. In particular:

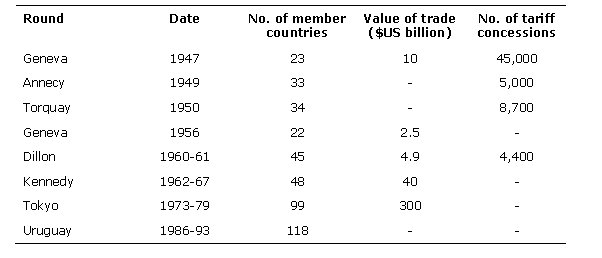

1.1.2 Achievements prior to the Uruguay Round

The principal mechanism for progress on trade liberalisation within the GATT have been periodic multilateral negotiating rounds. In all, there have been eight such rounds, starting with the Geneva Round of 1947 that established the GATT, and concluding with the Uruguay Round that ended in 1994 after having established the WTO. The primary focus of the majority of rounds has been promotion of multilateral tariff reductions, and the extension of the agreed reductions to all members in accordance with the MFN clause. The achievements are summarised in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: The GATT negotiating rounds

1.1.3 The exclusion of agriculture from the GATT

The issue of agricultural sector trade was effectively excluded from the GATT at an early stage in the Agreement's life. The general consensus of opinion was that agriculture was a unique sector of the economy, that, for reasons of national food security, could not be treated like other sectors. With the expansion of the manufacturing economy, agriculture was in relative decline. Political and social pressures demanded, however, that the decline be halted or slowed down, and that agriculture be protected from the full rigours of the international market.

It was not until the Uruguay Round that agriculture, as a sector, was eventually placed firmly on the GATT negotiating table; although certain agricultural products did previously appear in the negotiations, as individual commodities. The Dillon Round succeeded, for example, in cutting tariffs on Soya beans, cotton, vegetables and canned fruit to very low levels, and the International Wheat Agreement and the International Dairy and Meat Agreement were negotiated under the auspices of the Kennedy Round. In general, though, agricultural commodities remained outside the negotiating agenda.

As a result, agricultural trade was accorded "special treatment" and was effectively exempted from some important GATT rules:

1.1.4 Protectionism and international tension over agricultural trade

The limited relevance of the GATT to agriculture led to increasingly high levels of protection and support for agriculture, particularly in industrialised countries, where the market share of many traditional suppliers of imports went into sharp decline. Some net exporting countries, such as the USA, sought to maintain their market share by resorting to export subsidy programmes, whilst those exporters that were unable or unwilling to do this, saw their market shares decline further. International tension and disputes over agricultural trade arose with increasing frequency, and GATT institutions were often used in an attempt to resolve these disputes. In fact, 60 percent of all trade disputes submitted to the GATT dispute settlement process between 1980 and 1990 were concerned with agriculture.

The protectionist policies of industrialised countries created large distortions in world food markets, depressing the world price of temperate agricultural commodities to uncompetitively low levels, and generating global market instability.

It was not until the opening of the Uruguay Round in 1986, however, that agriculture was placed finally on the negotiating agenda. The desire to reduce continual friction between the USA and the EC over agricultural trade was one of the main reasons why a consensus was eventually reached to bring agricultural trade into the regulatory framework of the GATT. Consensus over how this was to be achieved, however, was at this point still far away, and it took seven years of negotiation before an agreement was finally reached.

1.1.5 Reasons for inclusion of agriculture within the GATT framework

The economic rationale for bringing agriculture within the framework of the GATT revolved around:

The issue of comparative advantage in agricultural production

Government interventions in agriculture distorted agricultural production in many countries and generated high levels of inefficiency. High levels of support to farmers in developed countries generated large surpluses, which were sold on the world market through the use of export subsidies, often greatly depressing the world price of many agricultural commodities. The effect was to distort international patterns of production away from those dictated by comparative advantage.

Since domestic prices in many countries, both developing and developed, had not been linked to world prices, the responses to changing international prices in both supply and demand that might have helped to dampen the annual world price fluctuations were absent.

1.1.6 The effect of protectionism on producers in developing countries

Agricultural protectionism also imposed implicit taxes on farmers in those countries where public sector support for farmers had been absent or negative. In developing countries, artificially low world prices created a downward pressure on domestic prices. This was frequently accentuated by domestic agricultural policies which effectively taxed producers.

1.2 Agriculture in the Uruguay Round negotiations

The Uruguay Round was launched in 1986 by the Punta del Este Declaration, in which the negotiating objectives of the Round were laid out. The objectives with regard to agriculture were described as follows:

An important element of the declaration was its explicit recognition of the effects that domestic agricultural policies have on trade. The Round would concentrate not only on the issue of border controls and export subsidies, but also on a broad range of domestic agricultural policy issues. Policies that subsidised producers would be subject to close scrutiny and negotiation.

1.2.1 The major actors and interests in the agricultural negotiations

The main actors in the agricultural negotiating group set up for the Uruguay Round were the USA, the EC and, to a lesser extent, the Cairns Group.

Developing countries outside of the Cairns group also had a strong interest in the negotiations, although their influence over the proceedings was relatively minor.

However, despite the importance of these other interest groups, discussions in the Uruguay Round were dominated by the differences between USA and the EC, the resolution of which determined the rate of progress towards an agreement.

1.2.2 The opening negotiating positions

When the negotiations on agriculture began, the positions of the EC and the USA were still very far apart. To emphasise its commitment to liberalisation the USA opened the negotiations with an unrealistic demand for the "zero-zero" option. Introduced in July 1987, this proposed that:

This position found support amongst members of the Cairns Group, which was itself proposing an immediate freeze on price support followed by the phased reduction of such support. The EC was, however, totally opposed to across-the-board reforms, and wanted instead to negotiate concessions on a commodity by commodity basis.

Japan, like the EC was keen to protect its farmers from international competition, particularly in the rice sector, for which it sought special treatment. This demand was made on the grounds that rice played a unique role in the diet, culture and environment of the country, and should therefore be treated differently from other agricultural commodities. Japan was, however, strongly in favour of measures to reduce export subsidies; as a net importer of agricultural commodities Japan would not find commitments in this area particularly demanding.

Meanwhile, the demands of developing countries were focused on their need for special and differential treatment within the negotiations. They emphasised the fact that agriculture plays a major role in the development of their respective countries, and that new GATT rules and disciplines should not inhibit agricultural growth by placing excessive constraints on government support policies.

The concern over the Uruguay Round's impact on those developing countries that were net importers of food, lay in the prospect that reduced surpluses in the North, resulting from a cut in permitted levels of agricultural support and export subsidies, would raise the international price of food, and, hence, the cost of importing it.

1.2.3 Slow initial progress in the negotiations

At the mid-term review in Montreal at the end of 1988, the negotiating parties in the agricultural group were as far apart as ever, and they had failed to produce an interim text for discussion by the group at the Montreal meeting. Meanwhile the Cairns Group refused to approve the draft texts of any of the other 14 negotiating groups until there was a text on agriculture. Following this failure, the main participants continued to search for a compromise:

The negotiating parties committed themselves once again to the long term objective of reducing government intervention in the above three areas of agricultural policy, and it was proposed that negotiations should proceed by seeking separate commitments in each of these three policy areas.

The EC and some other countries were reluctant, however, to adopt such an approach. The EC was particularly opposed to making substantial cuts in its export subsidies. Talks continued in the hope that an agreement could be achieved by December 1990, the original deadline for the conclusion of the Uruguay Round; but, the text presented there was rejected by the EC, and the deadline came and went without any agreement being reached. It was not until 1991 that the negotiators finally arrived at a consensus, whereby countries would agree to make concessions in each of the following three areas:

These areas eventually became the three main pillars of the final agricultural agreement. But, before that could happen the negotiators would have to establish the level of concessions that would be made, and that took two more years of tough negotiating.

1.2.4 The Dunkel Draft and CAP Reform: Paving the way to an agreement

At the end of 1991 the director-general of the GATT presented a comprehensive Draft Final Act, known as the Dunkel Draft, in the hope of bringing the Round closer to a conclusion. The Draft covered agriculture, as well as all of the other areas under negotiation in the Round. It included the first complete text on agriculture, in which quantitative proposals were presented with respect to concessions in each of the three major disciplines.

It was internal pressure within the EC to reform the Common Agricultural Policy, that gave the GATT negotiations the momentum that they needed. The MacSharry plan for CAP reform, that was eventually adopted in May 1992, included proposals that would bring the EC's agricultural policy much closer to meeting the targets outlined in the Dunkel proposals.

However, although the EC formally agreed to implement the MacSharry plan in May 1992, some obstacles to a GATT agreement still remained. The EC was still reluctant to make substantial cuts in export subsidies, and a question hung over whether the compensation payments of the CAP reform should be subject to domestic support reduction commitments.

1.2.5 The Blair House Accord

It was against this background that the American and EC negotiators undertook a series of bilateral discussions, that eventually led to an agreement, known as the Blair House Accord. The meeting that achieved this took place at Blair House in Washington in November 1992, and focused on making suitable amendments to the Dunkel Text. These amendments included the following:

|

||||