|

The implications of the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture for developing countries |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Chapter 3: Implications of the Agreement on Agriculture for agricultural policies and trade in developing countries |

||||

|

What this chapter is about

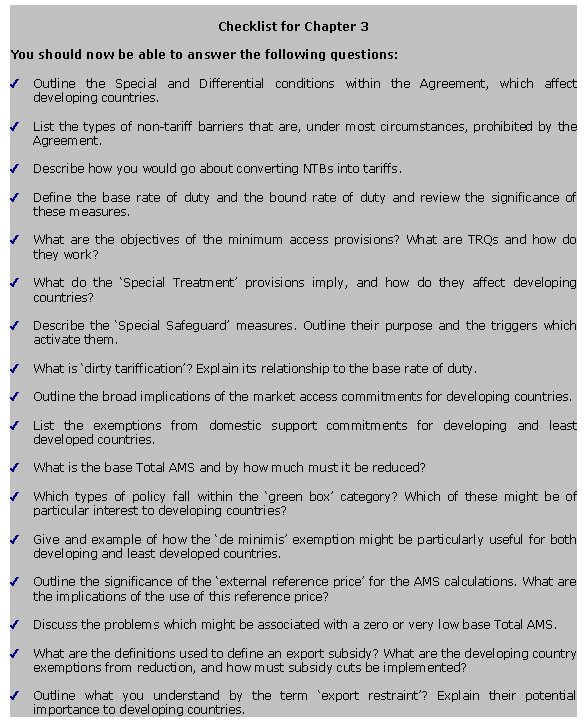

The purpose of this chapter is to look in detail at the Agricultural Agreement and the implications it has for agricultural and trade policies in developing countries. The chapter will examine the differential treatment that developing countries receive under the agreement, it will provide a guide to using and interpreting the agreement, and will examine to what extent full compliance with the agreement will affect existing agricultural policies in the developing country context.

Following the introduction, this chapter is divided according to the main sections of the Agreement, that is, market access, domestic support commitments and export subsidies. Each of these sections acts as a guide to the relevant Articles and Annexes of the Agreement, examining how the various paragraphs and clauses should be interpreted, and highlighting areas where developing country commitments are different from those of developed countries. Each section will look at the policy implications of compliance, both during the implementation period, and beyond. The chapter will pay particular attention to some of the practical details involved in complying with the Agreement, such as, for example, how to calculate an AMS, or how to establish the permitted level of additional tariff under the Special Safeguards provisions.

Aims of this chapter

What you will learn

The Agreement is likely to affect agricultural policies in developing countries in a number of ways. In the first instance, some areas of domestic agricultural policy and trade policy in developing countries will need to be modified in order to comply with the Agreement's provisions. It is these direct implications that will receive emphasis in the current chapter. The Agreement will also influence the agricultural policies of developing countries in a less direct way. This will occur, firstly, as a result of the Uruguay Round's impact upon the policies of the 'rest of the world', particularly, those of the developed countries; and, secondly, as a result of the impact on world markets and world prices, that reforms in the policies of the rest of the world will have. In the long term, changes in world markets and prices will provide new opportunities, as well as certain costs, that agricultural policies of developing countries will have to respond to. Changes in world market prices will, for, example influence the profitability of different commodity sectors, which may in turn, affect public sector investment policies. Analysis of these wider implications is, however, left until a later chapter, and for now we shall concentrate on the more immediate effects of the Agreement.

Before looking in more detail at the Provisions of the Agreement on Agriculture, it is useful to review the ways in which the provisions differ for developing and least developed countries compared to developed countries. This 'Special and Differential Treatment' as far as the Agricultural Agreement is concerned is introduced in Article 15. Thus:

It is now commonly accepted that disciplines of the Uruguay Round Agreement, affecting as they do many previously unregulated areas, have introduced a vast array of obligations that did not previously exist. At the same time, it has been recognised that the ability to meet these new obligations varies considerably from one country to another, and that while full participation in the new commitments may be appropriate for the more developed countries, it may not be so for less developed countries.

As a result, many of the new agreements, including the Agreement on Agriculture, contain within them provisions that differentiate the rights and obligations of member countries, according to whether they are developed, developing or least-developed. In general, developed countries are expected to participate fully in the new disciplines, while for developing countries the commitments are less demanding.

The UN definition of a least-developed country is the one used by the WTO. There are, nevertheless, some problems with this definition, since it is not designed to measure trade competitiveness and excludes some low-income countries that probably should be included. Greater ambiguity exists over the definition of a developing country, and this could possibly be a source of contention in future trade disputes. The principle followed in the GATT/WTO is that of self designation. In agreeing the schedules countries opted to be included in one category or another. However, the ultimate designation was potentially the subject of negotiation, and therefore of influence, by other member states.

The sections which follow will look in detail at the commitments of developing and least-developed countries with regards to the relevant provisions on market access, domestic support and export subsidies.

3.2 Market access provisions

As discussed in Chapter 2, the main elements of the Agreement's provisions on market access relate to tariffication, tariff reduction, minimum access commitments and a number of exemptions. The associated provisions and commitments are documented in the text of the Agricultural Agreement itself, in the Modalities and in the relevant Country Schedules. The first and the last of these are legally binding documents, whilst the Modalities were only binding up until the point at which the Country Schedules were submitted to the WTO.

In the Agreement itself the main article on 'Market Access' (Article 4) is short, and is limited to just two paragraphs. The first of these is concerned with tariffs and merely refers to the Country Schedules in which the legally binding commitments on tariff bindings, and reductions, as well as minimum access concessions, are to be found. The implication of this is as follows:

The second paragraph is also very short, and is concerned with NTBs. It requires that:

Article 5 is concerned with the Special Safeguard Provisions and Annex 5 with Special Treatment. The former allow countries, under particular circumstances, to raise tariffs above the level stipulated in their Schedules, while the latter permits a country to retain NTBs for certain sensitive products. Details of these exemptions are discussed below. The prohibited NTBs are provided in a footnote to Article 4, Paragraph 2 and are as follows:

3.2.1 Tariffication and tariff reduction

We will now look at the essentials of the market access provisions in more detail. Thus we focus on the process of tariffication, and the concept of the base rate of duty. The way in which tariffication has been carried out has been criticised by some commentators, as have the implications of the manner in which the base rates of duty have been calculated.

The base rate of duty for tariffied commodities

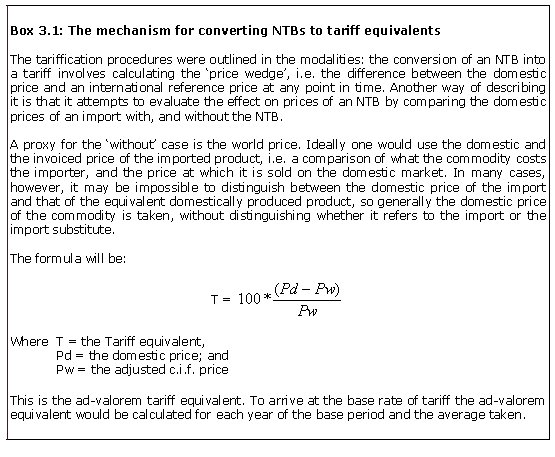

The obligation to convert NTBs into tariff equivalents applies to all member states, including developing and least-developed countries. This tariffication process involves converting the average rate of protection provided by NTBs during the base period (1986-88), into a tariff equivalent, and thereby establishing a base rate of duty for each product covered by the agreement.

The base rate of duty for products which are previously subject to a tariff

For previously bound tariffs, that is those with an upper ceiling, the base rate of duty is determined by this previous bound level. For unbound tariffs the situation is slightly different. Thus:

All signatories should have completed this process before submitting their Schedules to the GATT, with the resulting base rate of duty for each commodity listed in the relevant column of the Country Schedules.

The bound rate of duty

The bound rate of duty is listed in the Country Schedules in an adjacent column to the base rate of duty. This the level at which the final tariff for a particular product should be bound. It is, in other words, the maximum tariff that may be applied from the point of time at which it comes into effect.

The bound rate of duty for each product is the result of a reduction in the base rate of duty. It is established by:

The implementation period

The year in which the bound tariff becomes effective, again, depends upon the commitments made in the Country Schedule.

The sequencing of the reduction commitments as applied to tariffs should be implemented, according to Paragraph 7 of the Modalities, in equal annual installments. At the same time, it is worth noting that many developing country Schedules do not include annual commitments, but simply refer to reduction commitments being implemented over the 1995-2004 implementation period. It is worth remembering here that it is the Country Schedules rather than the modalities which are the legally binding documents.

3.2.2 Minimum Access Commitments

Details on how the level of minimum access commitments should be established were given in the Modalities rather than the Agreement itself. Since, as mentioned above, the modalities ceased to have any validity once the Country Schedules were accepted, the legally binding minimum access levels are now determined entirely by the extent to which the provisions of the Modalities were translated into commitments in the Country Schedules.

Where there were no significant imports, the Modalities obliged countries to provide minimum access opportunities, that would allow exporters of tariffied products (products that have undergone tariffication) to supply at least 3 percent of domestic consumption at the beginning of the implementation period, rising to 5 percent at the end of the implementation period, i.e. by 2004.

This implies that a proportion of the imports of a commodity which had previously been subject to NTBs would be allowed into the importing country at a reduced tariff rate. This quantity would be a minimum of 3 percent of the value of domestic consumption in 1995 at the beginning of the implementation, rising to 5 percent by 2004. Hence:

Compliance with minimum access provisions has generally involved the specification in the Country Schedule of an initial tariff rate quota (TRQ) and a final TRQ for each tariffied product involved.

These arrangements are laid out in the Country Schedules as follows:

In fact, the provisions on minimum access are somewhat ambiguous and have been interpreted in a variety of different ways:

However, the intention of the Agreement was also to protect the exports of existing exporters; i.e. to safeguard current access.

These arrangements are protected by the Agreement. They are different from the minimum access quotas, in the sense that they are not offered on an MFN basis. Nevertheless, they have been included in the quotas specified in the Country Schedules, with appropriate notes on which exporters enjoy the quotas.

These arrangements are different to the minimum access provisions. Where, previously, there was no market access, the minimum provisions have been agreed, but this is separate from any arrangements regarding current access. The two are not cumulative. It is possible, however, that minimum access quotas could be used to maintain existing bi-lateral agreements, rather than to offer concessionary tariffs on a MFN basis.

There is also uncertainty surrounding the procedures for allocating minimum access (rather than current access ) quotas:

The auction of such quotas may offer a more equitable solution; but, the price that is paid for auctioned licenses imposes an additional levy on trade, and could be construed as being in breach of WTO/GATT rules. These are issues that WTO still has to resolve.

3.2.3 Special treatment

The paragraphs regarding Special Treatment are found in Annex 5 of the Agreement. As has already been mentioned, circumstances do exist under the Agreement in which countries have been permitted to exempt certain products from tariffication commitments: the major exemption is that developing countries that had unbound ordinary tariffs, could offer tariff bindings instead of going through the process of tariffication:

Annex 5 describes the further conditions under which countries have been permitted to continue using non-tariff barriers to trade. Special Treatment, as this exemption is called, is only allowed for products that have been specifically mentioned in the Country Schedules as deserving such treatment (i.e. marked with the symbol 'ST-Annex 5').

Section A of the Annex describes the general conditions for the exemption designed to allow the maintenance of NTBs in certain circumstances. The provisions specify a range of criteria which have to be met concerning the proportion of imports in consumption (i.e. less than 3 percent), the provision of enhanced minimum access commitments and the use of particular domestic and trade policies. In particular, effective production restricting policies must be in place, and no export subsidies must have been used since 1986.

The effect of Section B is to provide developing countries wishing to protect sensitive agricultural commodities behind non-tariff barriers, with greater protection than would be the case under section A. At the same time, it was always unlikely that any developing countries would be applying production restricting measures for their basic foods, and thus be in a position to make use of this exemption.

3.2.4 Special safeguards provisions

Another important exemption from the usual market access commitments is the inclusion of Special Safeguard Provisions (SSP), described in Article 5 of the Agreement. This can be applied in two circumstances:

In order to apply this concession to a particular commodity, the commodity must be marked in the Country Schedule with the symbol "SSG" (paragraph 1). Apart from the 'triggers' or conditions which merit the use of this concession, the limitations in its use are as follows:

Quantitative trigger level

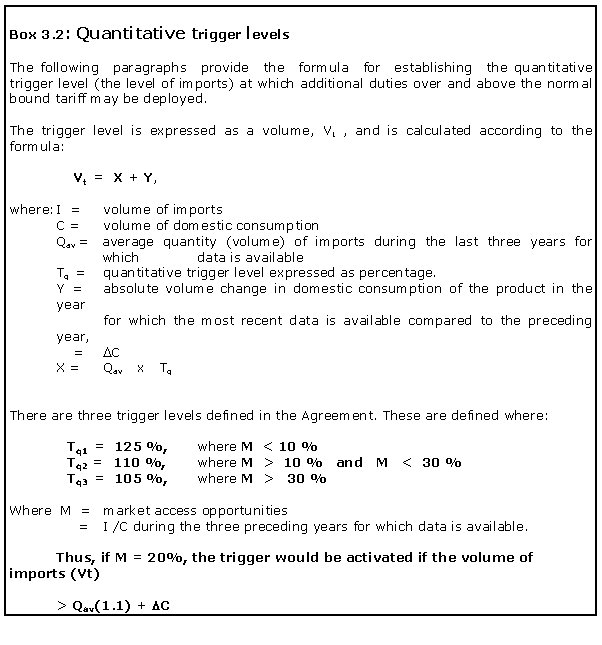

The formula describing the method for calculating the quantitative trigger can be found in Paragraph 4 of Article 5. It is described below.

The price trigger level

The reference price for calculating the price trigger level is defined in a footnote to paragraph 1(a) as being in general:

But, it may also be:

There is thus a degree of vagueness in how the trigger price should be established. Countries were not required to include intended trigger prices in their Country Schedules.

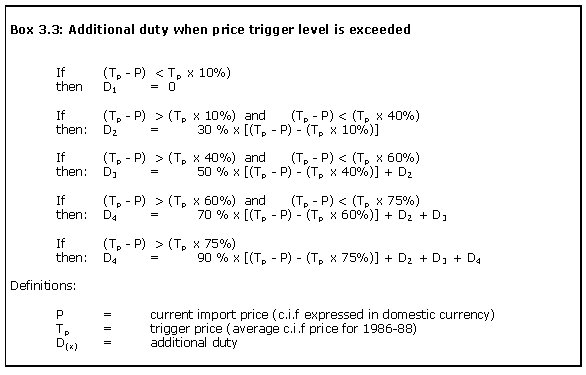

The formula for calculating the permitted level of the additional duty is provided in Paragraph 5. The value of this additional duty is dependent upon the degree to which the import price falls below the trigger level. This is outlined in Box 3.3:

To a certain extent the mechanism acts in the same way as a variable levy, in that as the import price falls the levy can be increased so as to dampen the price effect on the domestic market. However, it does not completely offset the fall in import prices, ensuring that domestic prices are not entirely insulated from the effects of changing world market prices.

3.2.5 Market access commitments: Implementation issues and policy implications

Having examined in detail the Agreement's provisions regarding market access, we now turn to the question of how these provisions will affect the trade policies of developing countries, and how the new policy constraints may affect their farm protection in the short and longer term.

Converting NTBs to tariff equivalents

The idea behind converting non-tariff barriers to trade into tariff equivalents, suggests that tariffication (as opposed to tariff reduction) should not have any immediate effect upon absolute levels of protection, since the rationale behind tariffication is to convert NTBs into a tariff that provides an equivalent level of protection to that existing by virtue of NTBs.

However, in so far as the levels of protection provided during the base period (1986-88) (for which the tariff equivalents have been calculated) differ from those actually prevailing during the period immediately prior to the start of the implementation period in 1995, tariffication could, in theory, have had an immediate effect upon levels of protection at the beginning of the implementation period.

That is not to say, though, that countries have immediately deployed the maximum permissible tariff at the onset of the implementation period; in many cases the tariff applied (i.e. the actual rate of duty) has remained lower than the base rate of duty.

It is apparent, therefore, that where levels of protection have fallen, or remained the same, since the base period, the process of tariffication need not have had any immediate effect on the level of protection provided to agricultural producers via trade policy.

Extending this notion further, one can also see that the effect of tariff cuts during the implementation period will also depend on how high the base rate of duty is compared with the actual rate of duty. To summarise:

High levels of protection during the base period give rise to high base rates of duty

The conversion of NTBs into their tariff equivalents should, according to the Modalities, have been based upon the difference between the domestic price and world price (border price) during the base period, expressed in domestic currency. The larger the difference is between the two, the greater the protection afforded by the NTBs, and the higher the resulting tariff equivalent.

In fact, the gap between world market prices and domestic prices in many developed countries was in many cases quite high during the 1986-88 base period, in so far as the world-market prices of major agricultural products were on the whole quite low, when compared to longer-run averages and more recent price trends. Additionally, the relatively low value of the dollar during the base period, had the effect of reducing the world price further, when expressed in domestic currency.

'Dirty tariffication'

Another reason why base rates of duty are likely to be quite high relates to what has been called 'dirty tariffication'. This expression describes the situation where countries have deliberately overestimated the levels of protection provided by NTBs in order to increase their operative base rate of duty resulting from tariffication. This has allegedly occurred because the task of converting NTBs into binding tariffs has been left to each individual country concerned. Clearly, countries wishing to retain scope for imposing high levels of protection for particular products, will have found it in their interests to be selective about the data they used for conversion.

In other words the conversion process could have been manipulated in such a way as to lead to a higher base rate of duty, than would be the case had the conversion been conducted in an unbiased fashion. Yet, so long as the results were not challenged during the verification process, which in general they were not, the resulting tariffs became legally binding from the point at which they were submitted to the WTO as part of the Country Schedules.

It should also be noted that if there had been no NTBs and tariffs with water in them (i.e. higher than required to give a certain level of protection), this would have resulted in higher tariffs than by using tariffication. The extent of 'dirty tariffication' is much disputed, and difficult to demonstrate. In any case, given that the contents of the Country Schedules now provide the legal framework for the implementation of the Agreement, the issue is academic.

Some implications of the market access provisions

It is very difficult to provide any firm diagnosis on the likely outcomes of the market access provisions. Much will depend on the manner of implementation. In particular on:

Structural adjustment programmes

As mentioned above, the binding nature of tariffication and tariff reduction depends largely upon the difference between actual rates of duty and base rates of duty. The above paragraphs suggest that base rates of duty are likely to be fairly high due to the choice of the base period, and in some cases because of 'dirty tariffication'.

Equally important, however, is the fact that actual, but usually unbound, tariff rates in some developing countries are in many cases currently lower than base rates of duty, which are bound, as a result of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), that exist independently of the WTO agreement.

Such SAPs are, in the short term, likely to place a greater constraint upon protectionist policies than are bindings under the WTO. In the longer term, however, tariff reforms under the WTO, are likely to be more influential, in that they are part of a permanent agreement, that will outlive SAPs, and prevent reversion to NTBs and higher levels of protection.

It will, in other words, provide a ceiling beyond which protectionism may not rise. Such a ceiling did not previously exist; moreover, in creating the ceiling, the process of tariffication also introduced the possibility of lowering it, and this is likely to be one of tasks that future WTO negotiating rounds will be concerned with.

Globalised tariff cuts

The effect of the cuts agreed in the Uruguay Round will be reduced, to an extent by the high level of the base rate of duty, and by trade policy reforms that have occurred since the base period. However the manner in which the base rates are to be cut may also act to further reduce the impact.

For example, if a minor commodity is subject to a base rate duty of just 1 percent, a 100 percent cut in the tariff will receive the same weight, as far as global tariff reduction commitments are concerned, as a 100 percent cut in the 200 percent duty on a major commodity.

If, for example, we assume a 100 percent tariff cut for the former, and just a 10 percent cut for the latter, the tariff on the minor commodities will have fallen from 1 percent to zero, whilst the tariff on the major commodity will have fallen from 200 to 180 percent. The average tariff reduction will equal : (100+100+10+10)/4 = 55, which easily meets the global reduction obligations.

Minimum access

The extent to which minimum access requirements will reduce this protection and encourage new imports is uncertain, and depends largely upon the pre-existing level of imports, and the commitments that have been made in the Country Schedules. At a minimum level of just 3 percent of domestic consumption rising to 5 percent, if the rules were followed closely, the impact of these commitments may not be very substantial. In any case, the minimum access provisions only apply to countries that tariffied, and not many developing countries followed this path.

Conclusion

This section has highlighted the fact that the Agreement and the Modalities both provided countries with some opportunity to avoid offering the sort of tariff concessions that would lead to a major increase in their level of imports. There is certainly evidence to suggest that some developed countries (e.g. EU, USA) have taken advantage of such opportunity.

In addition, the Special Safeguard Provisions provide countries with additional protection against surges in the volume of imports, or a fall in world prices, in the event that bound tariff rates prove insufficient for this purpose.

However, there are difficulties with generalising about the policy implications of market access commitments: the contents of the Country Schedules, that determine these commitments, vary considerably from one country to another, and from product to product.

In the longer term, the tariffication of agricultural trade barriers in the Uruguay Round, could act as a foundation for much deeper cuts in agricultural protection. But, at this point in time the overall effect of the Uruguay Round's market access commitments on the trade and agricultural policies of developing countries would not appear to be very substantial, at least in terms of the protection that they are able to afford to domestic producers.

An additional possible long-term effect of market access commitments might be felt by developing country exporters. Through the reduction the margin between the preferential tariff rates currently enjoyed by some developing country exporters, and the tariffs paid by other countries in developed country export markets.

3.3 Domestic support commitments

The importance of the Agreement on Agriculture with regard to domestic policy lies in it being the first time that a close link between domestic and trade policies has been formally recognised. Although the current implications for developing countries may, in most cases, be limited, the future significance lies in the fact that, for the signatories, the Agreement enshrines in international trade law limitations on domestic policy formation, and places constraints on the room for manoeuvre of policy makers. Thus, policies which 'distort' agricultural trade are likely to be increasingly untenable.

At the same time, it is apparent that the agreement is primarily designed to affect domestic policies in developed countries where, in many cases, export subsidies have been used abundantly, and where domestic agricultural policies are frequently geared to the subsidisation of agricultural production. In contrast, in many developing countries the sum total of policy intervention results in the taxation of the sector, particularly of the export producing sub-sector. In contrast to commitments to subsidy reduction, there is no provision in the Agreement which requires countries to reduce the volume of taxation.

3.3.1 Developing country exemptions

As noted above, the domestic support commitments are, in general, far less demanding on the agricultural policies of developing countries, than they are on those of developed countries. This is because:

Two important exemptions from domestic support reduction commitments for developing countries are provided in Article 6 paragraph 2 of the Agreement:

Least-developed countries, on the other hand, are exempt from all domestic support reduction commitments, but may not exceed the Total AMS as established for the base period (1986-88).

The aggregate measure of support (AMS), the indicator used by the GATT/WTO in order to quantify and reduce levels of domestic support, was discussed in Chapter 2. The Agreement, it was noted, commits its signatories to calculate the Total AMS for the base period (1986-1988): the Base Total AMS, and then, in the case of developed countries, to cut this by 20 percent during the 6 year implementation period.

An important consideration in reviewing the implications of AMS reductions is the fact that although most developing countries have no AMS reductions to make, the outcome of a very low or zero base Total AMS means that most developing countries cannot in the future introduce any price distorting support unless the policy falls within one of the specific exemptions.

3.3.2 Exemptions from AMS commitments: 'Green Box' policies

Chapter 2 introduced the concept of 'green box' policies; these being policies that are exempted from the AMS calculation by virtue of their being deemed not to have distortionary effects on trade. We will now look in more detail at the 'green box' and the AMS calculation, with reference to the relevant parts of the Agreement's text.

A full account of the 'green box' exemptions to domestic support reduction commitments, is given in Annex 2 of the Agreement. For a policy to be excluded from the calculation of AMS, and hence from reduction commitments, it must be deemed to:

Policies that may be included within the 'green box' are reviewed below. They are a summary of the list that appears in Annex 2 of the Agreement, to which readers may refer in order to see the exact text of the agreement.

General services

Policies under this heading involve programmes that provide services or benefits to agriculture or the rural community, but which do not involve direct payments to producers or processors. They include:

This exemption refers to expenditures (or revenues forgone) in relation to the accumulation and holding of stocks of products which form an integral part of a food security programme identified in national legislation. Expenditures may be excluded from AMS calculations provided that the following conditions are met:

Policies aimed at providing domestic food aid to vulnerable sections of the community can also be excluded from the AMS calculations provided that:

Certain types of direct payment to producers may be included in the 'green box' category provided that they 'have no, or at most minimal, trade-distorting effects or effects on production' and provided that the size of such payments, in a given year, is not related to:

The types of direct payment that are permitted are listed below:

==> De-coupled income support

This implies that for direct payments aimed at supporting the incomes of producers to be exempt from AMS calculations, it is important that they do not influence production decisions i.e., they should be "de-coupled" from production, and should not, therefore, have any effect upon what is produced or on how much is produced.

==> Government financial participation in income insurance and income safety-net programmes

This exemption is provided on the condition that such insurance only covers income losses in excess of 30% of average gross income and only covers 70% of that loss. Again, these payments should not relate to the volume or type of production, but should be based solely upon income.

==> Payments for relief from natural disasters

For payments of this kind to be exempt, they must be part of the assistance provided in response to an officially declared natural disaster in which the resulting production losses exceed 30 percent of the average production in the previous 3 years (or 5 years, excluding the years in which the highest and lowest production figures occurred)

==> Structural adjustment provided through producer retirement programmes

These include payments made to producers as part of a retirement programme in which the producers desist totally and permanently from the production of marketable agricultural commodities.

==> Structural adjustment through resource retirement programmes or through investment aids

These exemptions include direct payments made under resource retirement programmes, and with respect to investment assistance must be designed to assist the financial or physical restructuring of a producer's operations in response to 'structural disadvantages'. They may also be based on a programme for the re-privatization of agricultural land.

==> Payments under environmental programmes

This provision is aimed at allowing producers to be compensated for financial losses incurred as a result of clearly defined government environmental and conservation programmes. These include, for example, programmes that require producers to adopt particular production methods or inputs for the purpose of achieving environmental objectives. As such they are exempt from the usual condition that 'AMS exempt' direct payments should not be determined by the type and method of production. The amount of the payment is limited to the extra costs or loss of income resulting from compliance with the government programme.

==> Payments under regional assistance programmes

Payments in this category are limited to those made to producers in clearly defined 'disadvantaged' regions, in which the disadvantages "arise out of more than temporary circumstances". The region in question must be "a clearly designated contiguous geographical area with a definable economic and administrative identity".

3.3.3 Other exemptions from AMS calculations

The 'green box' exemptions listed above are probably the best known exemptions from domestic support reduction commitments. While they are of considerable importance to developed country agricultural policy, there are few groups of policies in the 'green box' category which are of major significance in developing countries. Other exemptions include the de minimis and 'blue box' provisions, of which the former is by far the most important.

==> The 'de minimis' provision

Described in Article 6, this provision offers policy makers additional room for manoeuvre. We discussed previously that where the AMS for a particular product constitutes less than 10 percent (5 percent for developed countries) of the total value of production of that commodity, the de minimis clause exempts that support from inclusion in the calculation of the Total AMS. This exemption also applies to non-product specific support.

This provision exempts direct payments made in conjunction with production limiting programmes, is of direct relevance to developed countries, (e.g. EU and US set-aside payments), but is of much less concern to developing countries where production limiting programmes are not at all widespread.

3.3.4 Calculating the total AMS

This section provides guidelines on the methodology for calculating AMS values. It summarizes the rules laid out in Annex 3 and Annex 4 of the Agreement. The basic idea behind the AMS calculation is to quantify, in monetary terms, the support provided by all policies that do not fall within any of the exempt categories discussed above. Only when such quantification has taken place, can a measurable reduction take place.

Verifiable AMS reductions require, firstly, that base period AMS values be calculated and, secondly, that current AMS values be established on an annual basis in order to evaluate compliance with the reduction commitments.

However, the modalities included a provision that allowed countries to gain credit for reforms in domestic support that had taken place during that period (e.g. the EU's CAP reforms). Hence, countries were given the option of using 1986 as the base period. The EU, the USA and Japan all took advantage of this provision, since by raising the level at which their domestic support started, their AMS reduction commitments were made less demanding.

The fixed external reference price

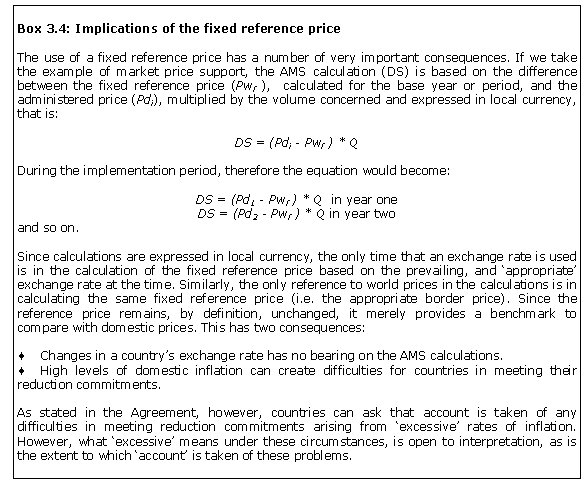

Since the calculation of AMS values entails the quantification of domestic support measures in monetary terms, this raises the question of which prices should be used in order to establish the appropriate monetary values.

The answer provided in the Agreement is that the price adopted should be what is referred to as the fixed external reference price. This is expressed in national currency, and defined as the average price prevailing during the base period.

Calculating the total AMS

The total AMS is established by summing the value of the product-specific AMS, the non-product specific AMS and the Equivalent Measure of Support. The methodologies for establishing the values of these is presented in the sections below. A Base Total AMS has already been calculated and notified in the Country Schedules. Current Total AMS values are calculated during the implementation period in order to establish compliance with reduction commitments. The following rules apply to AMS calculations:

The Agreement requires that AMS values be calculated on a product-specific basis for each agricultural commodity that receives:

==> Market price support

Market price support is to be calculated by establishing the difference between the fixed external reference price and the applied administered price, and multiplying the resulting figure by the quantity of production eligible to receive the applied administrative price.

Budgetary payments made to maintain this gap, such as buying-in or storage costs, are not included in the AMS. It is worth noting that the market price support component of the AMS applies only to products for which an administered price is actually set. Where a wedge between the market price and the fixed external reference price is maintained by import barriers alone, the market price support element is not included in the AMS calculation.

==> Non-exempt direct payments - e.g. deficiency payments

Support provided by non-exempt direct payments takes one of two forms for the purpose of calculating AMS values:

In these cases the total value of budgetary outlays are used as the measure of support.

Other non-exempt measures

These include input subsidies and other measures such as marketing-cost reduction measures.

The value of these measures are established either by using (a) the value of government budgetary outlays, or (b) the difference between the price of the good or service and a representative market price for a similar good or service multiplied by the quantity of the good or service.

In the case where the subsidy is covered entirely by government budgetary outlays, then the former methodology (a) is used. Where this is not the case, for example where government interventions in the market reduce the price of the good or service, the latter methodology (b) is applied. What constitutes "a representative market price for a similar good or service" in (b) is not clearly defined, and probably offers room for manoeuvre.

Non-product specific AMS

Support which is non-product specific shall be totalled into one non-product-specific AMS. It is not possible to calculate levels of market support as in the case of product-specific support. However, non-exempt direct payments, which are non-product specific, and therefore not aimed specifically at maintaining an administered price level, may be calculated on the basis of total budgetary outlays; other non-exempt measures may also be calculated in this manner.

Equivalent measure of support

The equivalent measure of support is to be calculated for all products for which market price support exists, but for which it is impracticable to calculate a market price support component (as described above) for the AMS. For these products market price support is calculated "using the applied administered price and the quantity of production eligible to receive that price or, where this is not practicable, on budgetary outlays used to maintain the producer price." To this value is then added the support provided by non-exempt direct payments and other non-exempt measures, which is calculated in the manner described above.

3.3.5 Domestic support commitments: Implementation issues and policy implications

As was noted previously, the attention paid to domestic support by the Uruguay negotiators came about as a result of the policy excesses in developed countries, and the trade distortions that the high levels of support there have caused.

In developing countries domestic policies have typically taxed producers rather than supporting them, and the value of the Total AMS, in terms of both the base period level and the current level, would be, in many cases negative, if carried to the logical conclusion.

Furthermore, since the product-specific and non-product-specific AMS values, are in such cases, often well below the de minimis levels beyond which AMS reduction commitments start to become effective, many developing countries have found that domestic support commitments have rarely posed a constraint at this point in time.

Nevertheless, there are in developing countries many domestic agricultural policies that should be included in the AMS calculation, particularly in the calculation of product-specific AMS values, even if it is subsequently found that the support they provide falls below de minimis levels, and need not, therefore, be subject to discipline.

At the same time, as most developing countries have zero AMS, the constraint may arise in the future if some price distorting support is introduced, when the zero base AMS will act as a ceiling on such support which is over and above the de minimis level. The following should therefore be noted:

Certainly de minimis provisions will exclude subsidies that fall below the value of 10 percent of total production from the AMS calculation, and this means that the Base Total AMS is bound at zero for those countries that implicitly tax their agricultural sectors. Furthermore, so long as future increases in subsidies do not exceed the "de minimis" threshold, then Current AMS will also remain at zero.

This implies that, leaving aside the problem of AMS reduction commitments, developing countries that are at present "taxing" their agricultural sectors will be bound never to raise their support levels above those excluded from the AMS calculation under the "de minimis" provisions.

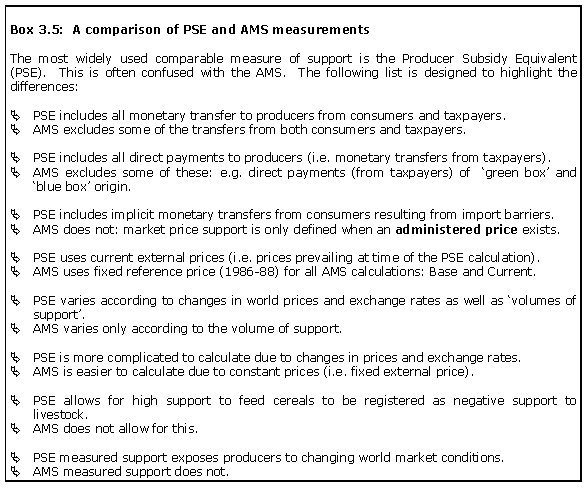

Before continuing, it is worthwhile noting that AMS measurements differ substantially from a more widely known and commonly used measure of support, the Producer Subsidy Equivalent (PSE). The following Box details the main points of difference. In essence these stem from the fact that the AMS is a much weaker, or less complete measure, and does not take account of a number of some significant forms of domestic support. It also differs in the role played by the external reference price which, as discussed above, makes the measure unaffected by exchange rate and world price movements.

The following sections outline some of the policies frequently employed by developing country governments, which may in future, if not at present, be affected by WTO commitments on domestic support.

Output price policies

Government administered output pricing has often been a major feature of developing country agricultural policy. However, unlike in developed countries where administered prices have generally been higher than world market prices, thereby providing support to agricultural producers, administered prices in developing countries have often been lower than international prices and have, therefore, effectively taxed producers. Accordingly, as noted above, the market price support component of the product-specific AMS has, for many agricultural commodities, typically been negative.

Traded input price policies

In an attempt to offset low output prices policy makers have often sought to provide subsidised inputs. These are frequently directed at specific commodities, as part of production packages that include seeds, fertilizers, pesticides and machinery, and credit. In such cases the subsidy would be included in the product-specific part of the AMS calculation, although the value of these subsidies often fail to offset the negative value of the market price support component of the AMS. Where input subsidies are not directed at specific commodities they would be included in the non-product-specific component of the AMS. It should be remembered that:

Subsidies on inputs that are non-traded, such as those on credit, water and electricity are also subject to inclusion within the AMS calculation, although it is not made entirely clear how the value of such subsidies should be calculated.

Marketing interventions

Governments in developing countries are frequently involved in marketing, either through the direct provision of marketing services by state agencies, or through the public funding of various marketing facilities.

Otherwise marketing interventions are excluded from the AMS calculation.

Other public investments

Most other public investments in the agricultural sector of developing countries are exempt from AMS commitments. They gain their exemption either through the specific exemptions accorded to developing countries, or through the 'green box' provisions:

3.4 Export policies: Subsidies and restrictions

3.4.1 Export Subsidy Commitments

As with domestic support commitments, the commitments on export subsidies have been introduced into the Agreement principally in response to developed country policies. Export subsidies have been a major component of agricultural policies in the EU and the USA, but have not, on the whole, played a very important role in developing countries. Consequently, the Agreement's export subsidy commitments do not, generally speaking, have major policy implications for developing countries. The definition of what constitutes an export subsidy, for the purposes of the Agreement is provided in Article 9. The following list summarises the definitions given in the relevant paragraphs:

3.4.2 Developing country exemptions

Developing countries receive some temporary and limited exemptions with regards to the export subsidies outlined above. Specifically they are permitted, during the implementation period only, to encourage exports with subsidies aimed at reducing the cost of marketing, processing and transport, provided they are not applied in a manner which would circumvent reduction commitments.

3.4.3 Reduction commitments

For those developing countries that do subsidise exports, the Uruguay Round agreement requires:

Again, as with other aspects of the agreement, the specific implementation rules were often only included in the Modalities, with the result that commitments are only binding to the extent that they appear in the Country Schedules.

3.4.4 Export restraints

Export policies in developing countries have generally concentrated more on export restraints, than on export subsidies. These have taken the form of taxes, quotas and prohibitions.

The Agreement introduces restrictions on the use of export restraints, where such restraints relate to foodstuffs. However, these restrictions do not apply to developing countries unless they are 'net exporters' of the particular foodstuff in question. At the same time, no definitions is offered as to what a 'net exporter' of a particular foodstuff might be in these circumstances. This will have to await clarification by the WTO when such a case arises.

The Agreement disciplines on Export Prohibitions and Restrictions are found in Article 12. For those countries, including developing countries, that are net exporters of a particular foodstuff, the following provisions apply to their use of export restraints:

|

||||