This section shows how floodplain river fisheries may be managed by their stakeholders. Section 4.1 describes how the resource may be sub-divided into different types of management units. Section 4.2 then provides guidelines on the strategic assessment of those units, showing the types of information needed to make useful management decisions. Menus of alternative management tools are then described in Section 4.3 for each of the different management unit. Finally, in Section 4.4., methods are given for monitoring floodplain fisheries to ensure the effectiveness of new management strategies.

Though this section focuses mainly on technical tools and assessments, it is re-emphasised that effective management will require far more than simply making a choice between say a reserve and a mesh size regulation. As indicated in Section 3.3, management requires a whole range of different roles. Only a few of these, such as research and fishery assessment contribute directly to the process of selecting technical tools. The majority of roles - including legislation, co-ordination, communication, enforcement and monitoring - are more intended to ensure that the rules are widely understood and supported by the different stakeholders, and also that they actually achieve the selected objectives for the fishery. Without this much wider management support, technical management will be worthless.

The technical proposals in this section should also only be read as guidelines for the management process, rather than as blueprint solutions for universal application. As emphasised in parts of Sections 4 and 5, the successful management of floodplain fisheries will need to develop gradually over a series of steps. Many important lessons will, no doubt, be learnt as new co-management strategies are applied. Managers should always make the best use of these lessons, rather than sticking rigidly to any pre-conceived format or plan.

Co-management will present a major challenge both to government and other stakeholders: managers should start in a few local areas and build gradually on that experience

Management units should be selected to achieve the maximum overlap between the range of authority of the management group and the distribution range of a fish stock

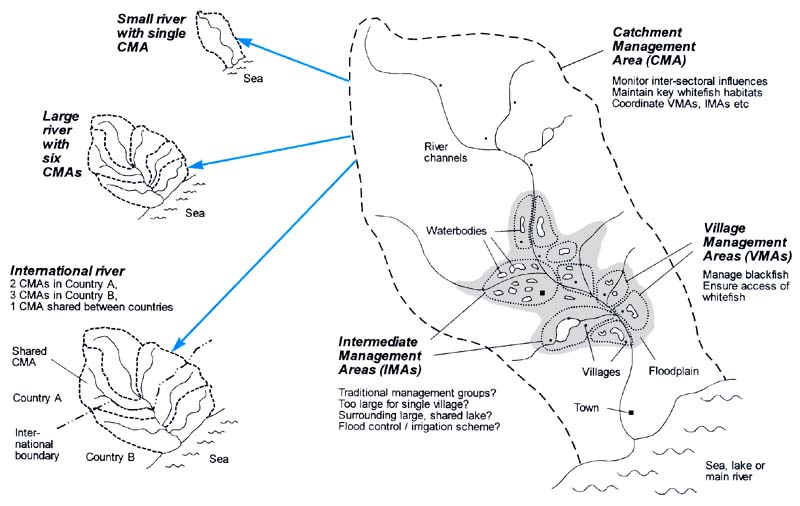

Section 3.1.2 introduced the idea of dividing the floodplain into a nested arrangement of fishery management units, and promoting the development of co-management partnerships in those units with the best opportunities for this type of management. The sub-division of a river system into management units should be based on the spatial interactions between the floodplain river environment, the fishing communities and the fish stocks. In practical terms, three main categories of management units may be identified: Catchment Management Areas (CMAs), Village Management Areas (VMAs) and Intermediate Management Areas (IMAs).

Figure 4.1 illustrates how a floodplain may be split up into these different units. All rivers should be expected to have many different potential VMAs, and maybe a few different IMAs. As discussed later, VMAs may sometimes be nested within IMAs. As illustrated on the left of Figure 4.1, a small river may be manageable with only a single CMA, while larger rivers may be better sub-divided into several CMAs. Rivers straddling international borders may even have some CMAs split between two countries (increasing the difficulties of successful management in those parts of the catchment).

Each of these management units will require different management contributions from each of their stakeholders, as discussed in Section 3. They will also require the use of different management tools, as discussed in the following Section 4.3. The following table briefly summarises the justification and requirements for the different management levels. Guidelines for identifying the different units are given in the following sub-sections.

VMAs provide the strongest management opportunities wherever fishing communities have traditional control over local waterbodies within areas small enough to manage effectively

Fishery management goals are most likely to be achieved when management rules are well adapted to both the physical characteristics of local resources and to the social priorities of local communities. The selection and enforcement of management rules may thus be best achieved by the local community, taking advantage of their intimate knowledge of their resources and their capacity for mutual monitoring and enforcement. Local village management areas (VMAs) will therefore provide the best starting point for most floodplain fisheries management strategies.

Floodplain fishery management units

| Management Unit | Justification and management needs |

|---|---|

| National / International | Large river systems may flow across many different parts of a country, or even between two or more countries. Their management requires institutions capable of making decisions and resolving conflicts on wide geographical, and sometimes political, levels. |

| Catchment Management Area (CMAs) | Floodplains are only a part of the overall river system. Many different sectors may compete or the valuable resources of the floodplain. Changes to the quality, quantity and timing of the flood due to upstream activities can all cause negative impacts on floodplain fisheries. Maintaining the joint productivity of fisheries and other sectors thus requires their coordination at a catchment-wide level. Whitefish stocks also migrate around the whole catchment, and require management at this scale. |

| Village Management Areas (VMAs) | The high local variability of floodplain river systems and their fisheries means that no single approach to managing each of the smaller units in a floodplain will succeed. Dividing the floodplain into a number of small, local units gives the flexibility needed for effective local management. Allocating use rights to these small management units may also give local communities the incentive to manage their local blackfish stocks for sustainable long-term benefits. |

| Intermediate Management Areas (IMAs) | In some parts of the floodplain, the geographical distribution of villages and waterbodies may mean that the catches in each village are more than usually dependent on the activities in their neighbouring villages. In such situations, co-operation between the different villages may be required to achieve management goals. This requires particular skills in communication and co-ordination, therefore IMA management may be expected to be more difficult than VMA management. |

Figure 4.1 River fishery management units

VMAs should be selected to achieve the maximum overlap between the range of authority of a social group (e.g. a village), and the distribution range of a blackfish stocks. Managers thus need information on the spatial distribution of four items: waterbodies, fish, fishing and existing management ‘institutions’. Regional data on some of these subjects may be available from existing records of the fisheries departments and planning agencies; local data will need to be collected by interviewing key members of each fishing community. Training on effective community research techniques may be required for this process. The distribution and behaviour of fish species will usually be the most difficult information to determine, and it may be necessary to assume that floodplain regions will have some local blackfish stocks wherever there are significant dry-season waterbodies.

VMAs may be identified by holding discussions in villages, based on the checklist of questions in Section 4.2, and bearing in mind the ‘Who should manage?’ issues raised in Section 3. Localities suitable for use as VMAs may also already be known by local fisheries officers. The best prospects exist in those fishing communities which have had traditional control over their own waterbodies, especially when their control is recognised and endorsed by government. There may also be some advantages in adopting local government boundaries, to take advantage of existing administrative abilities and systems of authority.

One or more ‘Catchment Management Areas’ (CMAs) will also be required for all river systems. CMA-level management would have three broad purposes:

monitoring and management of the impacts on the fishery from other sectors;

co-ordination of management activities in local VMA and IMA units, and communication of the successes and failures of alternative approaches between local units; and

management of migratory whitefish stocks.

Where possible, CMAs should be identified on hydrological grounds, as the geographic area from which water (and pollution etc.) drains into the river system. Where catchment boundaries do not overlap with administrative boundaries, some boundary adjustments may be needed to enable the participation of existing management agencies.

Small rivers may be manageable with only a single CMA wherever the managers can coordinate activities across the whole catchment area. Larger rivers may be more effectively divided up into two or more CMAs, either for hydrological reasons (e.g. where the river system has two or more discrete floodplain regions) or to divide the river catchment between separate administrative authorities. Since whitefish (and water, and pollution etc.) may still move between CMAs, multi-CMA rivers will require co-ordination by a river management forum. In the very largest rivers, such as the Ganges or the Mekong, international fora (such as the Mekong Secretariat) will be necessary.

Simpler management tools are required for IMAs, due to the increased difficulties of roles such as monitoring, communication, coordination and enforcement in these larger areas

Management opportunities for blackfish will be greatest in ‘bottom-up’ VMA-level management units. Whitefish may be primarily managed in the more ‘top-down’ CMA-level units. Between CMAs and VMAs, however, there may also be a range of ‘Intermediate Management Areas’ (IMAs), whose management needs and opportunities depend on the spatial relationships between waterbodies and communities. IMAs would include single large waterbodies (floodplain lakes) fished by two or more surrounding villages; and single villages or towns lying alongside a large, multi-waterbody floodplain system. Depending on the fishery problems at hand, IMA units may either provide an ‘umbrella’ over two or more VMAs, or completely replace them at the base of the fisheries management hierarchy. The following table illustrates the types of problems where IMAs may prove useful.

| Problem | Management Solution |

|---|---|

| A waterbody (e.g. large lake) is shared between a number of villages, giving significant overlap of blackfish stocks. Independent management by one village may be negatively affected by the actions of the other villages. | No spatial VMAs created, but village leaders control fishing activities of their own local people. IMA created with representatives of each village, to negotiate and agree rules to be followed at IMA level (i.e. throughout the whole waterbody). |

| A floodplain comprises multiple waterbodies, not closely associated with individual villages. Waterbodies are too remote for village-based monitoring and enforcement. | No VMAs created. Waterbodies are managed at IMA level using less ambitious management tools, and with representation from surrounding villages or districts with interests in the fishery. |

| Local hydrological modifications such as flood control schemes or impoundments disrupt whitefish migrations, to the cost of all of the impounded villages, or create fishing advantages for some villages and disadvantages for others. | VMA managers control fishing activities within their own local waters. An IMA is created with representatives of each village, to resolve local disputes and negotiate with other sectors. |

Simpler management tools are required for such IMAs, due to the increased difficulties of roles such as monitoring, communication, co-ordination and enforcement in larger areas. As for VMAs, management of these units will usually be easiest wherever traditional management institutions already exist. Where they are currently absent, new management institutions should only be proposed when substantial levels of management support can be allocated. In the first place, managers should concentrate on establishing VMA and CMA-level management, and work on IMAs only where some institutional structures already exist.

The appropriate management strategy for each fishery unit depends on the objectives selected for it and its current performance against those objectives

The local impacts of management tools are hard to predict and should always be monitored against the chosen objectives

Four categories of information are required to understand a fishery management unit and guide the local selection of technical management tools: environmental conditions, the distribution of fish stocks and fishing practices, and the ‘institutional arrangements’ currently in place for managing the fishery (see checklist in Box 2).

At the VMA and IMA level, much of this information may be collected directly from the local fishers collaborating in the co-management partnership. At the CMA level, managers will need to rely on more regional data sources, and on combining the knowledge of local units in different parts of the catchment. Though fishing communities may have only limited knowledge about wider fish migration patterns (e.g. about the full range of whitefish movements), they will usually know about the timing and direction of fish movements within their own fishing grounds and about their dry season survival locations. Most importantly, they will also usually know what actions would sustain their local catches, though they may never before have had the incentives to follow these actions. From a management perspective, the answers to the following critical questions should be found by the successful application of the checklist:

Are fish stocks relatively stable or in decline (smaller sizes, harder to catch)?

Which stocks are declining and are they blackfish or whitefish?

Which permanent local waterbodies do blackfish survive the dry season in (how could they be protected)?

Can whitefish access local fishing grounds from the main rivers (could management improve accessibility)?

Could the distribution of catch between different stakeholder groups be improved?

What changes in fishing (or water use) practices could help stop the decline in stocks or improve fisheries outcomes in some way?

| Box 2. Checklist of data required for effective management of floodplain river fisheries |

| ENVIRONMENT |

|

| FISH |

|

| FISHING |

|

| INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS AND OBJECTIVES |

|

The appropriate technical management strategy for each fishery unit then depends on the capacity of the co-management partners, the objectives selected for the unit, and its current performance against those objectives. From a quick examination, the most heavily exploited fisheries may be distinguished by the following characteristics:

Fishing gears with small mesh sizes (e.g. less than 4–5cm stretched mesh);

Small fish in the catch (e.g. less than 10–15cm in length, including both small fish species and small specimens of large species); and,

Many competing (chasing) fishing gears, used during the (inefficient) high water period.

Where measures appear necessary to improve the outcomes from the fishery, managers should select from the lists of alternative management tools proposed in Section 4.3. The selection of tools should take into account their likely impacts on the fish stocks and the fishing gears currently used in the fishery (and their owners), and on their acceptability to local stakeholders. Before moving on to the selection of technical tools, the following two sub-sections describe the types of impacts which should be expected for fish stocks and fishers.

The lists of management tools given in Section 4.3 indicate their theoretical benefits for fish stocks in each type of management unit. Such benefits are both based on common sense, and supported by the technical experience reported in Part 2 of this paper. Where blackfish stocks are locally depleted, for example, reserves may provide a good means of restoring their numbers. Where whitefish stocks are seen to decline following the introduction of barrier traps, the removal of the barriers may restore those fish species. The actual impact of the reserves or barrier regulations on the recovery of the preferred species may, however, be virtually impossible to predict in advance, due to the complexities of local conditions. For this reason, these management tools are recommended as simple approaches, which should always be followed up with monitoring of their impacts and further adaptive management as and when required (see Section 4.4).

Due to the competitive interactions between fishing gears, technical management approaches such as gear closures, closed seasons, and mesh/fish size limits always have benefits for some gears, and losses for others

Though the impact of management tools on the recovery of fish stocks may be difficult to anticipate, their impact on the distribution of catches between gears will usually be much more obvious. As described in Section 2.4, due to the competitive interactions between fishing gears, technical management approaches such as gear closures, closed seasons, and mesh/fish size limits always have benefits for some gears, and losses for others.

A basic understanding of the likely impacts of alternative management tools can be gained from simple information on the relative catches of each main fish species taken by each main gear type in each season. For VMAs, this information should be available from within the fishing community involved in the management decisions. For higher level management units, such information may be obtained either from catch sampling programmes, or from interviews with fishers.

With an overall knowledge of the catch pattern in the fishery, the expected gains from the management strategy for some gears can be easily balanced against the likely losses for others. This idea is illustrated in Figure 4.2 for a simple example with only two species, two gears and two seasons. Each of the three management strategies would have benefits for the users of gear A, and corresponding losses for those using gear B. While any of the three strategies may be useful for this fishery (especially if the catch of species A is the main objective), they clearly should not be implemented without serious consideration of their impacts on the users of gear B.

A real floodplain fishery would of course usually have more than two gears, along with many fish species and more than two seasons. The types of interactions between the gears would, however, remain the same, and could at least be identified as above for the main gear types and species. This simple, but multi-species, multi-gear approach should always be considered during the development of new management plans for floodplain river fisheries. The adoption of a given strategy should then be discussed between all the stakeholders likely to be affected (particularly those fishers relying on ‘gear B’).

Management plans should include a mixture of different tools for ensuring sustainability, raising revenues, and ensuring a fair distribution of benefits

This section describes the alternative technical tools which may be used by managers to achieve sustainable benefits from the fishery. As mentioned earlier, such technical tools are only one component of a fishery management plan. The plan should also list the management objectives for the fishery and clarify each of the roles needed for successful management, such as communication, monitoring, enforcement and so on. It should also identify which stakeholders have responsibility for each role (Section 3.5), and be revised as their understanding, experience and capacity increases.

No single technical management tool will answer all the objectives of management. A combination of tools should thus be selected for each fishery management unit, as appropriate to the local situation. The management plan should always include some tools for ensuring sustainability (e.g. reserves, barrier gear bans) and some other tools for raising revenues to pay for management (e.g. leasing, licensing). Management plans for some units may also include some tools for improving equity (e.g. bans of gears giving unfair advantages to their owners).

A wide range of different tools may be used to achieve each of these different objectives. Fishing activities, the environment and fish stocks can all, in some cases, be influenced by management. Some of the more useful management tools for floodplain river fisheries are listed in the following table, along with their primary objectives.

Where and when these tools are appropriate will depend not only on the technical features of the fishery (state of stocks etc.) but also on the capacity of stakeholders to carry out the roles needed to support the tools. In a newly established management area (village or catchment) it is important to begin with simple management interventions and allow co-operation and management capacity to develop. When a group of stakeholders have long experience of co-operation and have successfully managed their resource, the sophistication of technical interventions can increase.

| Figure 4.2 Hypothetical illustration of the effects of three management tools on the catches of two species, taken by two interacting fishing gears. |  |

|

A menu of fishery management tools for floodplain rivers

| Management Category | Management Tool | Primary Objective (s) |

|---|---|---|

| Managing the Environment | Environmental protection | Maintain overall integrity and productivity of river floodplain system |

| Habitat restoration | Maintain primary habitats for fish spawning, feeding, and migrations | |

| Sluice gate management | Allow access of fish to polders (only in hydrologically modified floodplains) | |

| Water level manipulation | Maintain dry season water levels to maximise fish survival and fry production (only in hydrologically modified floodplains) | |

| Managing who Can Fish | Waterbody leasing | Raise revenue Reduce conflicts between fishers (control access) |

| Gear licensing | Limit number of fishers / gears Raise revenue | |

| Managing the Amount and Type of Fishing | Mesh / fish size limits | Limit capture of small / immature fish |

| Reserves | Ensure some fish can survive the fishery to spawn and produce next year's stock | |

| Closed seasons | Limit capture of small / immature fish (flood season) Ensure some fish can survive the fishery to spawn (dry season) | |

| Dry season gear bans | Ensure some fish can survive the dry season to spawn and produce next year's stock | |

| Barrier gear bans | Allow access of (white)fish to spawning, feeding and survival grounds | |

| Managing Fish | Once-only species introductions | Increase productivity of fish stocks, where appropriate species are missing |

| Repeated fish stocking | Increase size of fish stocks, where natural breeding insufficient or depleted due to overfishing |

Assuming that the group of stakeholders involved in VMAs will usually be easier to co-ordinate and manage than those in either IMAs or CMAs (bearing in mind the possibility of conflicts within communities), more detailed management interventions will usually be possible at the VMA level. Stakeholders managing IMAs and CMAs must be less ambitious and should focus on negotiating agreement between lower level units and on controlling permanent fishing structures and any especially threatening operations. A summary of the general suitability of these tools to the different management levels is provided in the following table.

The following sections describe in more detail how these tools may be applied in different management units. The accompanying tables should be read as menus of potential management options. At each level, the feasibility of these options will depend on the strengths and skills of the co-management partnership.

Suitability of technical fishery management tools at different management levels

| Management Category | Management Tool | VMA | IMA | CMA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Managing the environment | Environmental protection |    | |||

| Habitat restoration |    |   |  | ||

| Sluice gate management |   |    | |||

| Water level manipulation |   |    |  | ||

| Managing Who Can Fish | Waterbody leasing |    |   | ||

| Gear licensing |    |   | |||

| Managing the Amount and Type of Fishing | Mesh / fish size limits |   |  |  | |

| Reserves | Whitefish |  |   | ||

| Blackfish |    |   | |||

| Closed seasons |    |  | |||

| Dry season gear bans |    |  |  | ||

| Barrier gear bans |  |   |    | ||

| Managing Fish | Once-only species introductions | Whitefish |   | ||

| Blackfish |   |   | |||

| Repeated fish stocking | Discrete waterbodies |   |  | ||

| Open floodplains |  |  | |||

As mentioned earlier, the more complex management interventions such as fish stocking should be avoided until the managers are well accustomed to making collective decisions and enforcing them, and a commitment to common goals is well established.

VMA management tools protect local blackfish stocks and ensure the access of whitefish to maximise local benefits

The following tools are suitable for use in VMA units to deliver benefits within the locality of the village. They are particularly designed for the protection of local blackfish stocks, but also to enable the maximum access of riverine whitefish into local fishing grounds.

A key requirement of VMA management plans must be the protection of local blackfish stocks throughout the dry season to ensure the success of spawning in the following year. Reserves, closed seasons and gear bans may best be used in combination to ensure some fish survival. Fishing communities will thus generally know where fish survive the dry season, and which gears particularly threaten them at this time.

Management which prevents the use of such gears in some of the primary local waterbodies may effectively protect fish stocks without excessively restricting the fishery. Permanent, year-round reserves may not be necessary.

To implement such tools within a VMA unit, most villages will require considerable external support. Even if the village has an existing authority managing natural resources, new skills may be needed to take on responsibility for the fishery. The involvement of an NGO or external project, may be vital to the early success of a VMA. Government is instrumental in increasing a VMA's capacity to manage by formally recognising the rights of these local stakeholders to manage the fishery through legislation. Government may also play a role in supporting the development of both technical and management skills within the village. As time passes and experience is gained, the reliance on external support should decline, and may even eventually disappear.

Tools for Village (Blackfish) Management Areas (VMAs)

| Management Tool | How (?), Objectives (→), Advantages ( ) ) | Disadvantages / Considerations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat restoration | ? | Desilt blocked channels between river and floodplain waterbodies | X | Labour intensive, depending on level of blockages |

| → | Maintain access routes of migratory fish into village fishing grounds | |||

| Village members may contribute labour | |||

| Waterbody leasing | ? | Divide village waters into discrete lease units | X | Social exclusion of un-leased fishers |

| ? | Allocate lease units by open auction (open to all bidders) to maximise revenue, or … | X | Only applicable in floodplains subdivided by clear physical boundaries | |

| (may include sub-licensing of fishing gears) | ? | Limit auction bidding to key stakeholders to improve co-operation with management or distribution of benefits | X | Knowledge that fish emigrate from lease-unit encourages high exploitation rates |

| ? | Use completely transparent lease system to prevent corruption | X | Short term leases may lead to over-exploitative extraction | |

| ? | Use long term leases (>1 year), in most discrete waterbodies to encourage sustainable investment and management | X | Long term leases may require credit facilities | |

| ? | Allow lessee to sub-license use of small fishing gears in lease unit | X | Long term leases may be resisted due to uncertainty of future profitability (so allow annual payment) | |

| → | Raise revenues for village and management | |||

| → | Avoid conflicts of open access fishing | |||

| → | Encourage commitment to sustainable management | |||

| Transfer temporary management responsibility to lessee (presence of lessee enables more effective enforcement) | |||

| Enable lessee to gain some income from sub-licensees, but also limit their fishing to increase profitability of own large, more efficient but costly gears | |||

| Fishing gear licensing | ? | Sell fishing licences for each gear type, specifying locality and season. | X | Social exclusion if privileged class created (especially if fishing positions determined by ancestral rights instead of lottery) |

| (by village, in un-leased areas) | ? | Where good fishing spaces are limited (e.g. for drift traps), use lottery to allocate licences | X | May be difficult to determine the sustainable level of licensing (so use adaptive management) |

| → | Limit overall fishing levels to ensure some fish survival | X | Difficult to monitor and enforce in larger management areas | |

| → | Avoid conflicts of open access fishing | |||

| → | Raise revenues for village and management | |||

| Gear licensing may promote equitable access and high employment (useful where communities dislike exclusion created by leasing) | |||

| Mesh / fish size limits | ? | Set minimum size limits for mesh sizes of each gear type and/or landing of fish | X | Difficult to optimise in multi-species fishery, as gains for large species balanced by losses for small ones |

| ? | Select size limit to benefit most commercially important species in catch | X | May exclude poorer groups from fishery (if traditionally based on capture of small fish) | |

| → | Limit capture of small / immature fish | X | May require short-term sacrifice for long-term gain | |

| Simple traditional concept | |||

| May be enforced at local level by peer pressure or local agreement | |||

| Dry season reserves / gear bans | ? | Restrict use of most dangerous dry-season gears (e.g. dewatering, poison, electric fishing, fish drives) in defined waterbodies | X | Limitation of fishing opportunities in reserved waterbodies |

| ? | Select deep, permanently flooded waterbodies | X | Traditional users may resist bans on such highly effective gears | |

| ? | Include some lake and some river waterbodies to protect different fish species | X | May be unnecessary, if natural environment (tree snags, water depth) prevents dry season over-exploitation | |

| → | Ensure some blackfish survive the dry season fishery to produce next year's stock | X | Reserves in large waterbodies may be difficult to enforce | |

| Easy concept, traditional and easy to formulate as law | X | Enforcement of bans on small, portable, but effective gears (e.g. poisons) requires strong community support | |

| Visible and easy to enforce, especially if close to village, or in much-used waterway | |||

| Flood season closures | ? | Restrict fishing activities by all gears during early flood season | X | Exclusion of traditional users of flood season resources (often the poorer members of society |

| → | Limit capture of small / immature fish | X | Limits income and supply of fish from fishery to months outside closed season | |

| → | Enable un-restricted migration of fish to spawning grounds | |||

| → | Ensure some blackfish can spawn without disturbance | |||

| Fish stocking | ? | Enclose waterbody (e.g. with barriers) to prevent escape of stocked fish | X | Costly |

| ? | Remove predators where possible to reduce fry mortality | X | Technical knowledge required for fry production | |

| ? | Stock valuable species of fish (usually every year) at start of flood season | X | Requires revision of traditional use and ownership patterns | |

| ? | Combine with closed season / gear bans / size limits to limit capture of fish until marketable size | X | May exclude poorer groups from fishery (if fished during growth season, or using restricted gears) | |

| ? | Harvest fish just before or during dry season | X | Requires infrastructure for funding | |

| → | Increase size of local fish stocks, where natural breeding levels insufficient | X | Not generally good for biodiversity (does not matter on small scale but becomes significant on large scale) | |

| → | Increase value of catch available from fishery | X | Requires raised level of education | |

| X | Requires repeat stocking every year | |||

| Barrier gear bans | ? | Restrict use of lateral barrier gears (between river and floodplain waterbodies), especially during early flood season | X | May be difficult to monitor / enforce if barrier gears remain in place for later drawdown fishing season, but… |

| → | Enable access of whitefish into local fishing grounds | X | Year round bans may be resisted due to loss of most valuable (drawdown) fishing opportunities | |

| → | Enable un-restricted migration of local fish to their floodplain spawning grounds | |||

| → | Limit capture of small / immature fish | |||

Barrier trap regulations and habitat restorations are useful for CMAs to maintain the long-distance migration pathways of whitefish

At the catchment management level, government will have the greatest capacity to take the lead (see Section 3.5). Co-ordination and communication will be important, as other IMA and VMA management units will be nested within each CMA. CMA managers should look at individual VMA and IMA management plans in the context of the wider catchment issues and consult with lower units wherever there is conflict. The encouragement of VMA-level management may also itself be an effective means of improving the overall state of catchment resources. Illustrations of successful VMA management plans may be the best way of promoting further uptake of these ideas.

Tools for Catchment (Whitefish) Management Areas (CMAs)

| Management Tool | How (?), Objectives (→), Advantages ( ) ) | Disadvantages / Considerations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental protection | ? | Limit use of dams, channelisation and impoundments (if already exist, restore natural style of habitats where possible) | X | Costly, depending on scale |

| X | May need research to establish appropriate habitats for restoration | |||

| → | Maintain full range of habitats used by whitefish as breeding, nursery and feeding grounds | |||

| → | Maintain channels used by fish as migration routes | |||

| Spawning reserves | ? | Locate in upstream whitefish spawning areas | X | Exclusion of traditional users |

| → | Ensure some whitefish can spawn without disturbance | X | Difficult to enforce by government, unless supported by local users | |

| X | May need research to establish appropriate reserve areas | |||

| Barrier gear restrictions | ? | Restrict use of river-wide barrier traps, especially in main channels, and during flood-season, upstream migrations | X | Exclusion of traditional users (barrier gears are efficient and may provide a large part of the local catches) |

| → | Enable access of whitefish to spawning, feeding and survival grounds | |||

| Easy for government to enforce (large, visible, stationary gears) | |||

| Fish species introduction | ? | Introduce high-productivity fish species into rivers where they are currently absent | X | Can only be decided at Government level and following specific international protocols |

| → | Increase overall productivity of fish community | X | Effects usually permanent and irreversible | |

| Introduced fish may become self-reproducing (once-only activity) | X | May have negative impact on biodiversity | |

Decisions made in other sectors such as irrigation, infrastructure etc., which may adversely affect the fishery, are also often taken at the catchment level. Regional government offices are again in the best position to ensure fisheries arguments are heard. Governments may need support and training to establish good working relationships between their CMAs and the lower levels of management units. NGOs and external projects may have important roles in this situation.

In addition to these co-ordination activities, CMA managers must also take the lead in the management of whitefish stocks for the overall benefit of the catchment. The tools listed in the following table may be most useful for this purpose. Barrier trap regulations and the general protection of the environment are thus used here at a catchment-wide level to ensure that the full migration pathways of whitefish are maintained. Due to their possibly negative local impact, such tools would not generally be proposed for local VMAs, and thus need to be supported top-down from the higher catchment authority.

Between CMAs and VMAs, there may be a range of floodplain systems which do not qualify as full catchments, and yet are too large for management as single village units

As discussed in Section 4.1.3, a range of ‘IMA’ floodplain systems fall in between CMAs and VMAs, being too small to qualify as full catchments, and yet too large to be managed independently by single villages.

Communication and co-ordination are vitally important roles for IMA units. External support from an NGO or project may be necessary to establish effective networks of information flow. Considerable care must be taken to ensure that institutional rules are fair, transparent and in line with the wishes of as many as possible of the various stakeholders. The relationship between the VMAs nested beneath an IMA or among the group of villages brought together under an IMA must also be clearly defined and widely agreed. This requires high levels of trust between stakeholders in neighbouring villages: it may take some time for a good working relationship to develop.

The following sub-sections illustrate tools which may be useful for IMAs working either as ‘umbrella organisations’ for several VMAs, or as a complete substitute for VMAs for large floodplain systems.

IMAs as umbrella organisations for VMAs

The main management issues for shared lakes are the control of overall fishing levels, the encouragement of cooperation between villages, and the reduction of conflicts

VMAs in isolation will not always be able to manage their local fishery effectively. If blackfish stocks overlap too much with those in other villages, a management decision made by one village and not the others will be less effective and may result in conflict. For example, gear restrictions or closed seasons made by village A, but not observed by village B, will benefit fishers in B, while fishers in A carry the cost. Hydrological modifications may also disrupt whitefish migrations (to the cost of all) or make some fish species highly vulnerable to overfishing by some villages (to the cost of others).

In these situations, IMAs may act as a forum for discussion between the different VMAs, and for their joint negotiations with the representatives of other sectors. While this may provide solutions, it will add an additional layer of complexity to the task of management, requiring even greater co-operation and therefore support.

For IMAs covering a large lake, fish stocks are less likely to be vulnerable to fishing and environmental stresses in the dry season, so the primary management issues would be the control of overall fishing levels, the encouragement of co-operation, and the reduction of conflicts. For IMAs with large shared seasonal floodplains, the protection of dry season survival locations may be a more important issue. As with VMAs, the more complex tasks - particularly stocking - should not be attempted by IMAs without an appropriate combination of institutional maturity and outside support, probably from both NGOs and government.

Floodplain environments are often physically modified, or empoldered, to improve agricultural production. Sluice gates in such polders are usually used to modify water levels for the benefit of agricultural production. Within these areas, VMAs may be able to operate using the tools described in Section 4.3.1. In addition, IMAs may ensure that the interests of fishers are adequately reflected in decisions affecting the operation of the sluice gates. Where the polders are a physical barrier to fish movement on to the floodplain, sluice gates may be opened when possible to allow the entry of the maximum possible numbers of fish (eggs, fry and adults) into the impounded floodplain waters. Later in the season, sluice gates may be closed when possible to maintain water levels in the dry season waterbodies and increase the survival of fish. Such hydrological management may cause conflict between the agricultural and fishery interests so some IMA-level forum for resolving such conflicts will usually be needed.

IMAs as alternatives to VMAs

Where floodplain systems comprise many waterbodies spread over a wide area with no associations with any particular villages, they may be too large for the detailed management approaches used in VMA units. In such cases, IMAs may operate without the underlying structure and support of individual VMAs.

IMA Tools for Resolving VMA Conflicts and Enhancing Opportunities

| Management Tool | How (?), Objectives (→), Advantages ( ) ) | Disadvantages / Considerations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fishing gear licensing | ? | Sell fishing licences for each gear type, specifying locality and season. | X | Social exclusion if privileged class created |

| X | May be difficult to determine the sustainable level of licensing (so use adaptive management) | |||

| → | Limit overall fishing levels to ensure some fish survival | |||

| → | Avoid conflicts of open access fishing | X | Difficult to monitor and enforce in larger management areas (need regular checking for licenses) | |

| → | Raise revenues for village and management | |||

| Gear licensing useful where habitat cannot be easily divided up into lease units | |||

| Fish stocking | ? | Enclose waterbody (e.g. with barriers) to prevent escape of stocked fish | X | Costly |

| X | Technical knowledge required for fry production | |||

| ? | Stock valuable species of fish (usually every year) at start of flood season | X | Requires revision of traditional use and ownership patterns | |

| ? | Combine with closed season/gear bans/ size limits to limit capture of fish until marketable size | X | May exclude poorer groups from fishery (if fished during growth season, or using restricted gears) | |

| ? | Harvest fish just before or during dry season | X | Requires infrastructure for funding | |

| → | Increase size of local fish stocks, where natural breeding levels insufficient | X | Not generally good for biodiversity (does not matter on small scale but becomes significant on large scale) | |

| → | Increase value of catch available from fishery | |||

| X | Requires raised level of education | |||

| X | Requires repeat stocking every year | |||

| Reserves | ? | Restrict all fishing in defined areas | X | Limitation of fishing opportunities in reserved areas |

| ? | Select deep, permanently flooded areas | |||

| ? | Select areas close to each village to spread access losses and management responsibility equally between villages | X | Exclusion of traditional users, especially if poor or elderly traditionally fished close to village | |

| X | Requires good co-operation between villages for effective enforcement | |||

| → | Limit total fishing pressure, to ensure some fish survive the fishery to produce next year's stock | |||

| Easy concept, traditional and easy to formulate as law | |||

| Visible and easy to enforce, especially if close to villages, or in much-used waterways | |||

IMA Tools for Managing Fisheries Inside Hydrologically Modified Areas

| Management Tool | How (?), Objectives (→), Advantages ( ) ) | Disadvantages/Considerations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sluice gate management | ? | Open sluice gates at time of maximum egg/fry densities outside gates | X | Opportunities for opening gates limited by flood-water needs of agricultural sector |

| ? | Invite fisher's representative to advise sluice gate committees on fishery requirements | X | Opportunities vary between years depending on rainfall patterns | |

| Enable access of pre-spawning whitefish, and inflow of their eggs and larvae, in to polder to increase production | |||

| Water level manipulation | ? | Close sluice gates during dry season to maintain water levels in polder | X | Opportunities for controlling water levels limited by dry season needs of agricultural sector |

| Provide dry season habitats to increase blackfish survival and production of next year's stock | X | High dry season water levels may reduce effectiveness of some fishing gears (e.g. dewatering, fish drives) | |

In South Sumatra, Indonesia for example, the extensive River Lempuing ‘lake district’ has traditionally been managed by an open access leasing system where control of the waters is fully transferred to the leaseholders for the year. This solves the problem of managing distant waterbodies, but does little for the conservation of the resource (since the leaseholders attempt to take the maximum possible catch within the year of their lease). The following proposed modification of this system to restrictive leasing with some waterbodies withdrawn each year as reserves would maintain revenue generation from the resource, while also promoting conservation.

Floodplain fisheries managers have to deal continuously with uncertainty. As they operate in an environment that is both complex and variable, the results of their actions are difficult to predict and hard to evaluate. A management strategy based on repeated adaptation will assist in dealing with these uncertainties. Indications of when and where adaptation is needed will depend on a feedback or monitoring system.

Fishery managers should work with irrigation committees to operate sluice gates for the joint benefits of both agriculture and fish

An adaptive management approach is needed for floodplain fisheries to fine-tune management tools (or select different tools) until the chosen objectives are achieved

As noted in Section 4.2, it will usually be very difficult to predict the exact outcome of introducing a given management tool or institutional arrangement, due to the complexity of the systems affected and to local variations in habitat characteristics, social factors, external influences, and so on. As a result of these uncertainties, an adaptive management approach is recommended for managers at all levels of floodplain river fisheries.

| Adaptive Management: |

|

IMA Tools for the Management of Remote Waterbodies

| Management Tool | How (?), Objectives (→), Advantages  | Disadvantages / Considerations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat restoration | ? | Desilt blocked channels between river and floodplain waterbodies | X | Labour intensive, depending on level of blockages |

| → | Maintain access routes of migratory fish into village fishing grounds | |||

| Village members may contribute labour | |||

| Restrictive waterbody leasing/ reserves | ? | Manage lease units as for VMAs, with associated objectives and advantages, but… | X | Limitation of fishing opportunities |

| X | Exclusion of traditional users? | |||

| ? | Remove some waterbodies from leasing system, as reserves (possibly rotating reserved waterbodies each year) | X | May be difficult to enforce reserves in very large systems, especially if in remote areas | |

| → | Ensure some fish survive the fishery (since total leasing may encourage overexploitation) | |||

| Appropriate where no communities are particularly dependent on single waterbodies, or associated with them | |||

| Barrier gear bans | ? | Restrict use of lateral barrier gears (between river and floodplain waterbodies), especially during early flood season | X | May be difficult to monitor/enforce if barrier gears remain in place for later drawdown fishing season, but… |

| → | Enable access of whitefish into local fishing grounds | X | Year round bans may be resisted due to loss of most valuable (drawdown) fishing opportunities | |

| → | Enable un-restricted migration of local fish to their floodplain spawning grounds | |||

The concept of adaptive management is illustrated in Figure 4.3. The processes of monitoring, evaluation and feedback are possible at various levels, both within individual strategies and for the management process overall. In either case the process is intended to increase knowledge of the effects of both technical interventions, such as gear restrictions, and institutional innovations. Ultimately this should improve management and so improve outcomes from the fishery.

Experimentation and learning can take place on a number of levels. At the VMA level, adaptive management is simply a process in which adjustments are made to the level of a management regulation or tool, or the mixture of tools being used, with the intention of improving the outcome from the fishery. If it is found, for example, that a new reserve does not increase the catch of ‘species X’ as much as hoped, it may be decided to introduce another reserve, or to add a ban on a certain dry season gear for other nearby waters. Feed-back from monitoring data is thus required to detect whether or not these management strategies are working.

For managers at the IMA or CMA level the picture can be more complicated. On one hand, they may be trying to protect whitefish (e.g. through restrictions on barrier gears). Here they can follow an adaptive approach in exactly the same way as managers in VMAs. But they will also have a role in helping VMAs learn from each others experiences: comparisons can be made between the outcomes of the different management strategies adopted by different villages and news of successful procedures shared. One village may thus determine the most effective way to establish and manage reserves within its waterbodies, while another may identify improved ways to stock fish. Similarly, one village may develop a good approach to resolving conflict while another has established a good system of communication within the village and with it's co-management partners.

| Figure 4.3 Diagram representing the possibilities for improved learning, between and within stakeholder groups, when adopting an adaptive approach to fisheries management |

How quickly lessons can be learned from adaptive management will depend on how actively adaptive strategies are implemented. Technically, there may be advantages in making large changes rather than small ones, since the results of small changes may be impossible to distinguish from normal variability in the environment. But large changes often carry higher risks, and taking big risks is not recommended, particularly in the early stages of establishing management capacity. As noted earlier, with improving management skills and confidence of the co-management team, the technical sophistication of the tools can increase and so too can the degree of risk the team is prepared to take. The temptation to attempt to impose strategies on VMAs to speed up the learning process should be avoided. Technical advice to VMAs must be directed to improving local livelihoods and reducing risk, not to increasing the knowledge at CMA or IMA levels.

The results of the monitoring programme should show clearly whether or not the community's objectives for the fishery are being achieved

As adaptive management of floodplain river fisheries takes place at all levels in the management hierarchy, it requires contributions to monitoring from all three major categories of stakeholder: communities, government and intermediary organisations.

Communities

The information used to monitor the fishery will depend on the objectives chosen for it and may include ecological and socio-economic data

Whether collecting monitoring data for VMAs or for CMAs, there will be real advantages in promoting the active participation of local fishers, including:

In VMAs and the smaller IMA units, fishing community members have good incentives to participate in the management and monitoring activities, as the results have the most direct relevance to themselves and their community. The degree of formality in this monitoring will, as mentioned above, depend on both stakeholder preferences and the type feed-back needed for higher levels.

Government managers should note that their community-based partners should not be expected to monitor themselves simply to relieve the work load of the fisheries department. Fishers may only contribute effectively to this process if they are actively involved both in choosing the management tools for their fishery, and the types of monitoring required for their adaptive management.

Government

Some fishing communities have traditionally practised ‘adaptive’ management approaches for centuries within their local area. In modern times, this process is becoming more difficult as local floodplain resources are increasingly impacted by the activities of a range of different sectors, sometimes well away from the local area. Such VMA-level managers may then find it difficult to determine whether changes in their fishery's outputs are due to their own management practices or to other influences from outside the village.

The adaptive management of a sub-divided catchment may therefore be most effective with both local monitoring within units such as VMAs, and comparisons between units at the CMA level. CMA-level managers may thus be most able to distinguish management impacts from those due to external factors by comparing VMAs with and without different types of management tools.

CMA managers are also best placed to monitor long-term trends in the catchment and take a broad perspective on many different activities within the catchment as a whole. Such a comparative adaptive management approach would also enable lessons to be learned in one village to be transferred to the local managers of other units. Though results will always depend on local circumstances, the effectiveness of management tools such as reserves, closed seasons and so on may then be determined gradually in each catchment, based on local experience.

Catchment managers, who will nearly always be government staff, should thus be responsible both for managing whitefish stocks at the CMA scale, and also for assisting the managers of all of the other smaller sub-units in the interpretation of their monitoring data. For the monitoring of whitefish stocks, CMA managers may need to rely both on data from government field staff, supplemented by data from any villages also managing their own fisheries for these species. While this ‘adaptive co-management’ strategy emphasises the decentralisation of management responsibilities to the lowest possible levels, it will still require major inputs from all levels of government.

Intermediary organisations

The role of NGOs or other intermediary organisations in monitoring will depend on their role within the management system. In some Asian countries, NGOs are important organisations in many grass-roots, community development activities. Where an NGO takes such a role within this system, their involvement in monitoring may include the organisation of participatory monitoring within the VMAs and the facilitation of flows of information between VMAs at the IMA/CMA level.

Intermediary organisations, such as research institutes or (other) NGOs, that are not involved in the day to day management can play a useful role in monitoring the operation of the institutional arrangements both at the VMA level and between the different partner organisations. Their independence as external agents may give them the objectivity required to analyse breakdowns and find solutions.

Monitoring changes in the wider environment may help to explain unexpected changes in the fishery

The participation of fishers in monitoring programmes lets them see directly the impact that management is having

Feed-back may take the form of an exchange of direct experience between fishers, a more elaborate internal data-gathering exercise within the community, or a formal monitoring exercise supported by outside agencies. The detailed what and how of monitoring is determined by the institutional context: who will use the data and how decisions will be made.

Detailed data collection by communities in all VMA-level units would be neither possible nor necessary in the heavily populated floodplains of Asia. Where VMAs are established and functioning effectively, formal data collection may be unnecessary for village-level decisions. Indeed, many traditional management systems have evolved successfully without formal monitoring. Management learning at VMA level can thus be based on ‘common knowledge’, derived from co-use of the resource in conditions where mutual observation is possible and secrets are hard to maintain. For management learning at higher levels, experiences might be passed to other VMAs by gatherings and exchanges or lessons distilled by outside field workers.

However there are a number of circumstances where a more formal monitoring system, that may include outside processing and analysis of data, will be appropriate. This may be where:

In all cases, it must be remembered that formal monitoring data is expensive to collect and that evaluation is not always simple. Managers of higher level management units should therefore be sure that they need and will use the information that they request. This is particularly true where fishers are being asked to contribute data or bear the cost of its collection. Evaluation will be simpler for some types of data than others, and managers should be sure that they have the necessary analytical skills. Where evaluation involves value judgements of different stakeholders, it will be very helpful to decide criteria for evaluation before the outcomes are assessed.

The discussion below is directed mainly towards the collection of data at the more formal end of the monitoring spectrum. This emphasis reflects the interests of the likely readership of this document. It should not disguise the fact that, while the sorts of issues covered will be the same, most monitoring at the village level will tend to be informal.

In general, three different categories of monitoring data may be required. Firstly, information will usually be needed on the current state of the fishery, and the benefits being generated from it. Such data may relate to the abundance of fish stocks, the size of catches being taken, or the socio-economic benefits received by fishers. If these are increasing, it may indicate that the management measures are being effective. If they are not, additional data will be required to understand why.

Secondly, information on the inputs to the fishery is thus required, in order to explain the outputs. Influential inputs may include of technical and ecological factors, such as the amount of fishing and the condition of the river environment. Finally, the effectiveness of the management partnership and the management tools used will also be uncertain, benefit from adaptive improvement and therefore need monitoring. Guidance on the collection of the three types of monitoring information is given below.

Catchment managers should help local unit managers to understand the changes in their local fisheries, and pass on important lessons to other units

For the more formal monitoring systems, the types of information which need to be collected depend on the objective of management (see below). Since the achievement of nearly all these example objectives depends on the health of fish stocks, it will generally be useful to monitor the ecological state of the fish (e.g. their abundance). However it must be remembered that management interventions also affect other objectives and these must also be considered. For instance, the introduction of leasing, to increase government revenue, could reduce access by subsistence fishing households, thus affecting equity. Therefore, it is often be desirable to monitor the socio-economic state of the fishery (e.g. its current productivity, profitability and the distribution of benefits between stakeholders). To encourage village members to participate in management, it will always be useful to monitor at least some sort of indicator showing the social benefits being obtained from the fishery. The following sub-sections provide guidance on the collection of monitoring data on fish abundances and on socio-economic benefits.

Monitoring fish abundance-‘CPUE’data

CPUE data may be compared with figures from previous years to illustrate whether fish abundance levels are rising or falling

If fish stocks are twice as abundant this year than last year, it may be expected that a standard unit of gear will catch twice as many of them. The relative abundance of fish may thus be estimated from ‘catch-per-unit-effort’ (CPUE) data from the fishery. CPUE's may be estimated much more easily than the total catch of the fishery. They also indicate the current state of fish stocks more clearly than total catches, since the latter may kept high temporarily by increasing effort levels, even when stocks are in decline. CPUE figures should be estimated as follows:

CPUE figures may be estimated either from a single catch of one fisher on one day (‘period C’=1 day), or from the combined total catch of several fishers over a defined period. In either case the measured catch should always be divided by the actual number of fishing effort units used in its capture. Where several different CPUE estimates are available for a single gear type in a given period (e.g. from different fishers), an average CPUE figure may be calculated.

| If the objective is: | then, monitor: |

| revenue to government | total income from all leasing / licensing etc. |

| conservation of fish species X | abundance of fish species X |

| biodiversity of fish community | abundance of all individual fish species |

| profits of village members | income from fishing and associated costs |

| equity / benefit distribution | distribution of income / costs between stakeholders |

The units used for estimating CPUE are also critical, and vary between gear types. As shown below, the measure of ‘fishing effort’ may need to indicate how many units of gear were used, their size, and how long they were fished for.

CPUE data should be collected to compare with figures from previous years, to illustrate whether fish abundance levels are rising or falling. When comparing this year's figure with earlier ones, managers should be aware that the ‘catchability’ or effectiveness of fishing gears changes greatly between seasons. Catchability of barrier traps, for example, is highest when fish are migrating off the floodplains with the falling waters; catchability of many chasing and hoovering gears rises in the dry season when fish are most concentrated; catchability of set-and-wait gears may be highest when fish are actively foraging for food. CPUE levels in the current year, must only therefore be compared with those for the equivalent periods in previous years. Since the timing of the seasons varies between years, CPUE's may best be calculated as the average for each season (e.g. the wet season, the falling-water season and the dry season) rather than for individual calendar months.

Managers must also be sure that each gear type is only compared with the same gear type, and that the characteristics of that gear are not changing over time. If a new type of screen is used in a barrier trap, for example, its effectiveness may be increased and its CPUE's are then no longer comparable with those of the previous type. Those gears which are traditionally used in the fishery and are not likely to be modified in future offer the best prospects for monitoring fish abundances by CPUE levels. CPUE's should never be averaged across different types of gears.

If formal monitoring is being undertaken in VMA units, CPUE data may be recorded directly from fishers, perhaps by providing them with a simple form to complete on a daily or weekly basis. Managers should realise that some fishers may not wish to complete such forms, for a variety of reasons. Managers should therefore be prepared to offer full explanations of the adaptive management strategy. Providing fishers with cash or other incentives for their co-operation may or may not be appropriate. In licensed or leased fisheries, the management agency may be able to insist that catch and effort data is submitted by licensees / lessees, as a condition for their access to the fishery or the auction next year.

In CMA-level management units, agency staff may need to collect their own CPUE data. In this case, staff should only sample data direct from fishers, at wholesale (first-sale) markets, and not from traders at public (secondary) markets. At the market, samplers must be sure that the catch they are measuring represents the whole catch of only one gear type, and not a mixed catch from several gears. They must also determine the amount of fishing effort directly from the fisher, since this will rarely be known by fish traders or anyone else.

Measures of fishing efforts for different gear types

| Gear Type | Measure of fishing effort |

| Set-and-wait gears | Number of gear units (standard-sized gear, set for a standard period, e.g. per trap, when always set overnight) Number of gear units × time set (standard-sized gear, set for a variable period, e.g. per trap per hour) Number of gear units × size × time set (variable sized gear set for a variable time period, e.g. per metre of gill net per hour |

| Chasing gears | Number of gear units × time actively fished |

| Barrier gears | Number of barriers trap units × time set |

| Hoovering gears | Usually for a stated waterbody, with no specific units. Assuming standard fishing practices, CPUE's may be simply expressed as the total catch from the waterbody by that gear type. The success (catchability) of hoovering gears, such as dewatering, may however be strongly affected by dry season water levels: this may make CPUE's difficult to compare. |

Monitoring socio-economic benefits

Socio-economic monitoring programmes may demonstrate both the overall profits of fishing, and their distribution between different stakeholders

Evaluation of the contribution of management measures to increasing income or improving equity requires an understanding of both the net value of catch and its distribution between different stakeholder groups. Relying on data collected by routine monitoring for such an analysis is not recommended. If there are additional social objectives such as empowerment of the poor, these will also be difficult to evaluate through simple data collection techniques.

In formal monitoring systems, changes in the economics of the fishery can be monitored by collecting data on both the value of catches and the costs of fishing. Fishing costs may need to be subdivided between the costs of time, fishing gears, bait and so on, and the fees paid for access to fishing grounds, e.g. by sub-licensees. In many of the more open floodplain fisheries, great care is needed in extrapolating the results from individual households.

In addition to seeing whether socio-economic benefits are rising or falling over time, monitoring may be required on the distribution of impacts on different stakeholder groups, and their sub-categories:

Estimation of this distribution will usually require more detailed survey designs than needed for simple CPUE or income data, and will always need to be adapted to local conditions and fishery structures. Information will usually be required on the total numbers of fishers in different categories, the gears they use, and the average catch values and fishing costs for each gear type. This information is often highly sensitive and fishers may be particularly reluctant to declare it. Managers may need to guarantee the confidentiality of the information to protect the interests of the fishers. Presentations of socio-economic monitoring data may need to be averaged to avoid revealing sensitive information about individual fishers. Wherever possible, however, the monitoring and reporting process should be made as ‘transparent’ as possible, to minimise the submission of false data.

Since environmental conditions change naturally from year to year, managers will need to examine long-term trends and not expect immediate answers

As well as monitoring the outputs from the fishery (as related to the objectives), managers may also need to monitor any changes in the inputs to the fishery. In addition to the application of the management tools, important factors may include both the overall level of fishing (the numbers of fishers and gears etc.), and environmental factors such as water levels, and changes in land use patterns. Such data may help to explain observed changes in the fishery which do not seem to be due to the changes made to the management strategies and technical tools.

Monitoring environmental conditions

Though over-fishing may change the species composition of the multi-species catch, it rarely reduces the overall catch from the fishery. Total catches may, however, be reduced by changes in the environmental quality of the floodplain system and the wider catchment. Impacts on water quality are particularly important here, as are modifications of critical fish habitats (e.g. spawning habitats) by users of other sectors.

In addition to man-made impacts, environmental conditions also change naturally from year to year, causing significant variations in the productivity of fish stocks. Managers should thus expect their fish catches (and other monitoring outputs) to change significantly between years. Management actions should be made on the basis of long-term trends in outputs, rather than a simple comparison between this year and last year. Environmental data may also be collected to help interpret year-to-year variations in outputs.

Important environmental factors to monitor thus include:

Monitoring the amount of fishing

High levels of fishing may be responsible for declines in preferred species, and may not be prevented by some types of management tools. Having a reserve, for example, may not prevent the build up of very high levels of fishing in the waters around it. Monitoring the overall amount of fishing in terms of the ‘fishing effort units’ discussed previously is difficult for a multi-gear fishery, due to the differences between effort units. Managers should instead aim to collect simpler comparative data on fishing, such as:

Adopting co-management partnerships is a significant change in management of floodplain fisheries: difficulties should not be underestimated

The adoption of co-management approaches is a significant change in the way floodplain fisheries are managed and will take some time to develop. The institutional arrangements to support this development are a critical influence on the effectiveness of the approach in meeting its objectives. Developing a set of arrangements that are, and remain, appropriate is therefore an important task.

In keeping with the cyclical, adaptive approach to the technical aspects of fisheries management discussed above, the approach to developing this new style of management should avoid rigid predetermined formats. Rather, it should attempt to develop solutions through continuous self-examination and repeatedly updating and improving its approach. This requires monitoring of the stakeholder groups in a co-management agreement and the way they co-operate in order to manage.

Development as a process

An openness to learning will help develop this new approach to management

Solutions will be found by continual self examination and repeated improvement of approaches

Recent literature has placed particular emphasis on the idea of development as a process1. This emphasises the importance of retaining flexibility, learning from experience, and recognising both the importance of social context of outcomes and the dynamic nature of development. This contrasts to the more conventional view of making such changes using a very controlled or ‘blueprint approach’ with a fixed and predictable relationship between project inputs and project outputs.

Traditional monitoring systems are of limited use when the development of a new approach is treated as a process. These monitoring systems are mostly based on a set of predetermined indicators, intended to quantify particular outcomes: they will rarely show why such outcomes are achieved. Monitoring of organisational impacts, such as enhanced capacities of stakeholders, changed perspectives or empowerment, is particularly difficult. New kinds of information generation and communication are required. In contrast to more traditional projects (such as road construction or agricultural input delivery), development of a new system of fisheries management can not be judged from a single objective or one professional perspective. If obstacles to an effective co-management partnership are to be resolved, the perspective of each stakeholder group must be understood and taken into account.

Monitoring of the effectiveness of the change to a co-management style for floodplain fisheries must therefore examine those factors which determine both the effectiveness of individual organisations and the effectiveness of the relationships between them. The success of these relationships will influence all aspects of the creation, adoption and enforcement of management rules and the resulting outcomes from a fishery.

The explicit use of process-based approaches in fisheries management has been very limited, but guidelines can be obtained from experience in other sectors in Asia. For example, as co-management partnerships are being established, monitoring the process of their development should be carried out on a continuous basis. This will pick up successes and failures early and allow improvements to practice to be made before styles of management become too established and difficult to change. When the co-management partnership has become more experienced in its relationships, process monitoring may become less frequent, perhaps with shorter, more issue-focused visits, or when support is requested by the partnership.

Another useful area of guidance from work in other sectors refers to who should be involved in process monitoring. Breakdowns in the co-management partnerships will often be due to conflicts between the main partners or result from inadequate capacity of a partner to carry out their agreed roles and responsibilities. Therefore, it may be helpful to include researchers from outside the core partnership to help with process monitoring. The intermediary organisations such as research institutes, other NGOs or projects may have critical inputs here. Such contributors should ensure, however, that their own perspectives and beliefs do not influence their judgement of unfamiliar local situations.

Though invaluable in providing insights about the management partnership, process monitoring will not be easy. Difficulties may arise if managers feel threatened by researchers who document unplanned as well planned outcomes, especially if the local managers feel criticised by the outsiders. The modifications to improve the process of changing management, which are the objective of such process monitoring, may also be difficult to achieve if they are seen as signals of failure by outside funding bodies. Both of these problems can be moderated if the approach is explicitly adaptive, and the need for periodic change is seen as being normal rather than as a failure to control resources effectively. Process monitoring should be a means of developing stakeholders' capacity for participation, and not as a means of allocating blame for management failure.

Though process monitoring is now being used in the management of natural resources, it may still be unfamiliar to many fisheries departments. Much further work is required on its use for the development of fisheries co-management partnerships. In the mean time, fishery managers should recognise the need for this type of monitoring, and request advice from wherever it may be available, e.g. other government departments where it has been used, NGOs or international development projects.

The funding required for monitoring programmes should be raised from the fishery

The collection, analysis and presentation of data from monitoring programmes is essential for effective management, but requires significant inputs of both time and money. The costs associated with such activities should ideally be raised from the fishery by some component of the management plan, such as a leasing or licensing scheme. Authorities who receive money from such existing schemes should also be aware that some of these funds may need to be reallocated to pay for the improved management of the fishery.